Abstract

Background/Aims

Data are scarce on endoscopic sedation practices outside the United States and Western Europe, particularly from developing nations. An Internet survey was used to assess endoscopic sedation practices in developing and developed countries.

Methods

Responses to a Web-based survey of sedation practices from 165 expert endoscopists from 81 countries were analyzed. The most common sedation method was defined as that used for >50% of endoscopies within a country.

Results

Responses were received from 84 endoscopists practicing in 46 countries (51% response rate; 32 responses from 22 developing countries and 52 responses from 24 developed countries). A combination of benzodiazepine and opioid was the most common method for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in 40% of the countries and for colonoscopy in 56% of the countries. For propofol and unsedated endoscopy, the corresponding figures were 8% and 19% for EGD and 18% and 10% for colonoscopy. No single sedation method accounted for >50% of EGD and colonoscopy cases in 32% and 17% of the countries, respectively. There were no significant differences in the proportions of developing and developed countries using combined benzodiazepine and opioid, propofol, or unsedated endoscopy.

Conclusions

Sedation is used for most endoscopic procedures worldwide, with sedation practice not differing significantly between developing and developed countries.

Keywords: Endoscopy, Sedation, Survey

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic sedation practices are changing worldwide, driven by market forces and the availability of drugs that enhance sedation.1-3 Recent surveys in the United States4 and Switzerland3 have improved our understanding of sedation practices in these nations, and a collaborative study provided data regarding sedation practices within other countries of Western Europe.5 Little is known about the practice of sedation in other parts of the world, however, particularly in developing countries. Accurate data regarding worldwide sedation practices can help steer policy-making, resource allocation, professional training, and clinical research.

In the current study, we performed an internet-based survey of leaders within the World Organization of Digestive Endoscopy to investigate endoscopic sedation practices globally. We selected these individuals for inclusion within the survey, reasoning that they (1) teach and travel throughout their country and therefore possess useful information regarding national sedation practices; (2) have access to email and the internet; and (3) are motivated to respond to a survey because of their academic interests. Our aims were: (1) to obtain data regarding sedation practices and trends throughout the world, with particular attention to differences between developing and developed countries, and (2) to assess the potential utility of an internet-based survey for obtaining endoscopic data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Survey

A ten-question survey (Appendix) was developed by the authors. Part 1 (3 questions) asked for the respondent's observations regarding sedation methods and trends in sedation practices within his or her country. Part 2 (5 questions) addressed the respondent's personal sedation practices, (customary sedative drugs, method of sedative administration, physiologic monitoring, and use of ancillary personnel). Data from exploratory questions (2 questions) regarding endoscopist satisfaction with sedation methods and endoscopist estimation of post-procedure recovery times were obtained but are not reported here. A Web-based format was created and tested internally by the investigators. The survey took approximately 5 minutes to complete.

2. Selection of the endoscopists

A panel of 165 endoscopists was personally selected by one of the authors (JDW), using a contacts database related to his position as the President-Elect of the World Organization of Digestive Endoscopy. The panel represented 81 countries. Criteria for inclusion included: non-United States residence, senior practicing endoscopist, and leadership in the international endoscopy community as evidenced by one or more of the following: leadership role in an international endoscopic society and/or journal; leadership within the endoscopic community in his or her country as evidenced by an active national teaching and lecturing schedule; or, leadership in national endoscopic societies and/or meetings. During October 2005, a cover letter was sent by e-mail from the authors to the 165 recipients asking for voluntary participation in the survey and providing an electronic link to a website where the survey could be completed. The cover letter offered the respondents an option of responding electronically or by fax. Two reminders were sent by e-mail at one-week intervals following the initial request.

3. Data collection and analysis

Electronically submitted responses were automatically downloaded into an Excel database (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington) and responses that were received by fax were entered manually into the same spreadsheet. The survey was closed and the data analyzed one week after the final reminder was mailed. Responses received from individuals who were not on the original mailing list were excluded from analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel. For the purposes of the data analysis, sedation was divided into the three common methods: no sedation; propofol-based sedation, and benzodiazepine/opioid-based sedation. The "majority sedation method" was defined as the method that was used for >50% of endoscopies. Countries were categorized as "developing" or "developed" based on the categorization established by The World Bank.6 Comparisons between groups were analyzed using the chi-square test and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

1. Respondents

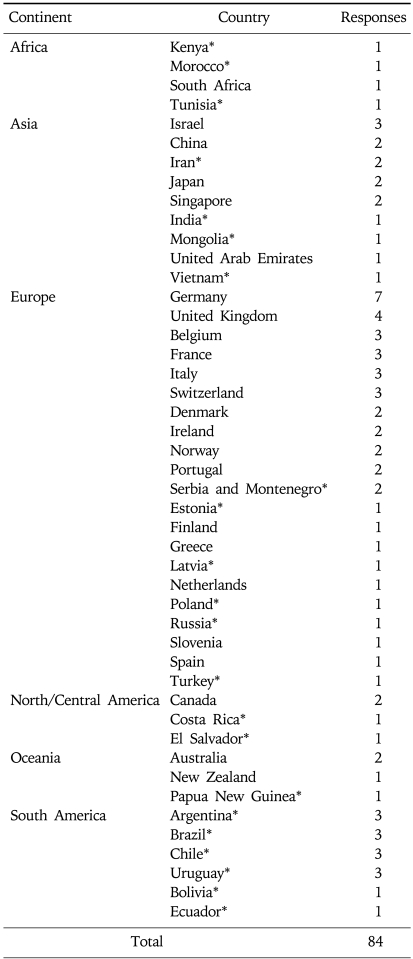

A total of 84 responses were received from physicians in 46 countries, representing response rates of 51% (physicians) and 57% (countries) (Table 1). The response rate from developing and developed countries was 32/77 (42%) and 52/88 (59%), respectively. The difference in response rate for developing and developed countries was statistically significant (42% vs 59%, p<0.05). There were 4 responses from Africa, 15 responses from Asia, 43 responses from Europe, 4 responses from North/Central America, 4 responses from Oceania, and 14 responses from South America.

Table 1.

Survey Responses by Country

*Developing country.

2. Endoscopic sedation practice

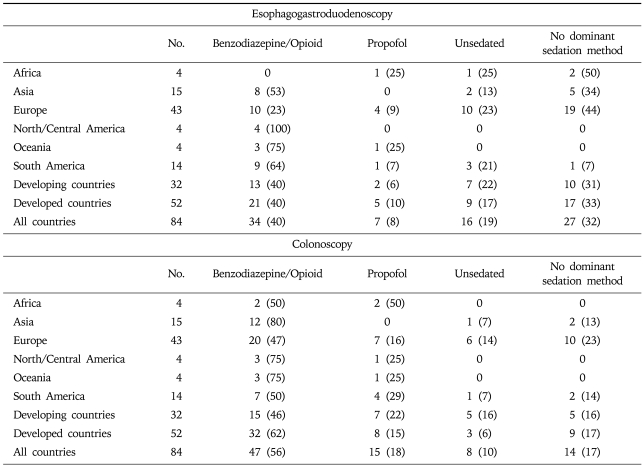

Questions 1 through 3 on the survey referred to endoscopic sedation practices within the respondent's country. The respondents' observations regarding the majority method of sedation for EGD and colonoscopy within their country (Question 1) are reported in Table 2. For EGD and colonoscopy, 57/84 (68%) and 70/84 (83%) of respondents, respectively, indicated that a single sedation strategy (unsedated, benzodiazepine/opioid, or propofol) was used for the majority (>50%) of procedures performed within their country. Conversely, 27/84 (32%) and 14/84 (17%) indicated that sedation comprised a combination of all three sedation methods such that no individual method accounted for >50% of cases (i.e. no "majority method").

Table 2.

The Majority Sedation Method Grouped by Continent for Colonoscopy and Esophagogastroduodenoscopy as Indicated by Survey Respondents*

*Data expressed as number (%).

Respondents indicated that a benzodiazepine/opioid combination was the majority method of sedation for 34/84 (40%) and 47/84 (56%) during EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. Physicians from developing nations indicated that a benzodiazepine/opioid combination was the majority method of sedation for 13/32 (40%) and 15/32 (46%) during EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. Among respondents from developed countries, the comparable figures were 21/52 (40%) and 32/52 (62%) during EGD and colonoscopy (p>0.05). Notably, 8/15 (53%) and 12/15 (80%) of endoscopists from Asia indicated that a benzodiazepine/opioid combination was the preferred strategy for EGD and colonoscopy, respectively.

Among all respondents, propofol was the majority method of sedation for 7/84 (8%) and 15/84 (18%) of respondents during EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. Endoscopists from developing countries indicated that propofol was used during 2/32 (6%) and 7/32 (22%) of EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. This compared with 5/52 (10%) and 8/52 (15%) among those from developed countries. The difference in propofol use between developing and developed countries was not statistically different for either EGD (2/32 (6%) vs 5/52 (10%), p>0.05) or colonoscopy (7/32 (22%) vs 8/52 (15%), p>0.05).

Unsedated endoscopy was the majority method for a relatively small fraction of respondents. Overall, 16/84 (19%) and 8/84 (10%) indicated that unsedated endoscopy was practiced in >50% of all EGDs and colonoscopies, respectively. The difference in unsedated endoscopy between developing and developed countries was not statistically different for either EGD (7/32 (22%) vs 9/52 (17%), p>0.05) or colonoscopy (5/32 (16%) vs 3/52 (6%), p>0.05). Among the eight respondents listing unsedated colonoscopy as the majority method, six were from Europe (Norway - 2, Poland - 1, Russia - 1, Serbia and Montenegro - 2).

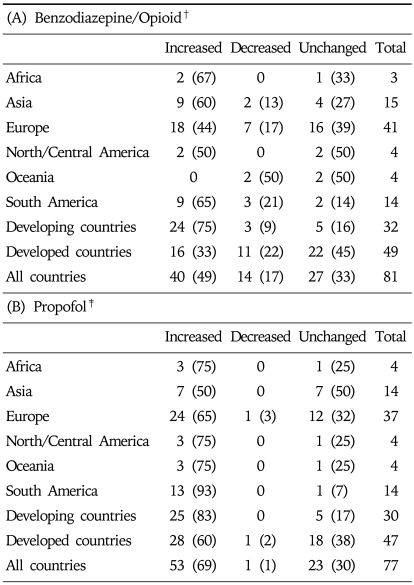

Items 2 and 3 on the survey dealt with trends in sedation practice during the previous 5 years. Overall, 40/81 (49%) of respondents indicated that benzodiazepine/opioid use had increased during the past five years (Table 3). A significantly greater fraction of physicians from developing than developed countries believed that benzodiazepine/opioid use had increased within their nation during the past 5 years (24/32 (75%) vs 16/49 (33%), p< 0.05). Among all survey respondents, 53/77 (69%) believed that propofol use for endoscopic procedures had increased within their country during the past five years. The difference in response between physicians from developing and developed countries was not statistically significant (25/30 (83%) vs 28/47 (60%), p>0.05).

Table 3.

Respondents' Observation Regarding Trends of Benzodiazepine/Opioid (A) and Propofol (B) Sedation within Their Country in the Past 5 Years*

*Data expressed as number (%).

†3 respondents failed to answer question.

‡7 respondents failed to answer question.

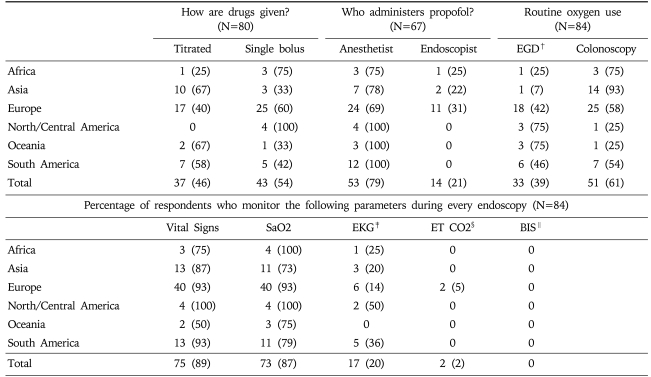

3. Personal endoscopic practice

Questions 4 through 8 dealt with the respondent's personal endoscopic practice. Overall, 23/81 (28%) respondents indicated that they used propofol in most cases. Respondents practicing in developing and developed countries used propofol with equal frequency (9/30 (30%) vs 14/51 (27%), p>0.05). Within nations where benzodiazepine/opioid usage is the majority method of sedation, midazolam was strongly preferred to diazepam (49 vs 3), while the choice of opioid was almost equally split between meperidine and fentanyl (14 vs 13). Most respondents monitored vital signs and oxygen saturation (75/84 (89%) and 73/84 (87%)), while only 17/84 (20%) respondents performed routine electrocardiographic monitoring (Table 4). Supplemental oxygen was routinely administered by 32/83 (39%) and 48/83 (58%) of respondents during EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. The use of supplemental oxygen, electrocardiographic monitoring, and pulse oximetry did not differ significantly between endoscopists from developed and developing nations. The use of capnography was infrequent among respondents 2/84 (2%) and none reported use of the bispectral index (a brain wave monitor designed to assess the depth of sedation). Among respondents using propofol, 21% indicated that it was administered under their supervision rather than by a dedicated anesthesia provider (Table 4). However, this practice varied considerably among physicians from different regions of the world.

Table 4.

Respondents' Personal Sedation Practices*

*all data expressed as N (%).

†EGD, esophagoduodenoscopy.

‡EKG, electrocardiography.

§ET CO2, end-tidal CO2.

∥BIS, bispectral index.

DISCUSSION

Sedation enhances patient tolerance and acceptance of endoscopic procedures, but adds cost, risk of complication, and delays the resumption of normal activity.2,7 The practice of endoscopic sedation varies from country to country due to social, cultural, economic and regulatory influences.8-10 Although surveys have depicted practices of sedation in developed nations, principally the United States1 and Western Europe,3,5 minimal data exist about sedation practices in developing nations. Because sedation is often central to endoscopic practice, data regarding sedation practices can enhance research, policy development, and training.

An internet-based world-wide survey offers the potential to generate data inexpensively and efficiently regarding world-wide practices, including in developing nations. Although response rates to internet-based surveys have been low historically, we achieved a relatively high response rate in our survey because we targeted contacts known personally to the authors. Further, the survey participants are widely considered to be national leaders in endoscopy. Consequently, they are uniquely qualified to observe sedation practices within their country.

Our results corroborate the observations of the EPAGE study of Western European practices5 and nationwide surveys of sedation practice within Great Britain,11 Spain,12 Finland,13 and the United States1 which suggest that sedation is the majority practice in 75 and 90% of developed nations, during EGD and colonoscopy, respectively. Likewise, our results support the conclusion of previous studies that the use of sedation is increasing throughout most of the world, and conversely, unsedated endoscopy is diminishing.

The results of this study also corroborate observations from Western Europe3,5 and the United States,1 indicating that a benzodiazepine/opioid combination is the preferred method of endoscopic sedation worldwide. Still, the use of propofol is expanding both within the United States and in other developed nations. Notably, 79% of respondents who indicated that benzodiazepine/opioid use in their region had decreased in the past 5 years also believed that propofol use had increased, suggesting that propofol is being used in these countries in place of benzodiazepine/opioid. A recent survey of endoscopists in Switzerland indicated that 43% had used propofol regularly during the past two years, and 81% administered propofol themselves without the assistance of an anesthesiologist.3 The authors propose several possible reasons for this increased utilization of propofol including less willingness of the patient to tolerate pain and discomfort, increased patient awareness of and demand for sedation, and the economic advantage associated with the use of endoscopic sedation in a competitive marketplace.

The practice of endoscopic sedation in developed and developing nations was remarkably similar in nearly all respects. We observed no significant difference with respect to use of sedation, choice of sedation agents, performance of unsedated EGD and colonoscopy, expanded use of propofol for endoscopic sedation, patient monitoring, or use of supplemental oxygen. Thus, these data suggest that over the past 5 years sedation practices in developing nations have been "catching up" to practices in developed nations.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the data regarding practices on the national level reflects experts' personal observations and perceptions and is subject to the effect of recall bias. It is possible that physician responses to questions about personal or national sedation practice reflected preconceived beliefs about practice patterns internationally rather than actual practice. Although there was generally high concordance among observers within one country regarding national majority practices and/or trends in national sedation practices, there were several instances of discordance. Second, the relatively low response rate of 51% may influence the results and the small sample size may introduce the potential for referral bias. Furthermore, there was a significant difference in response rates between physicians from developing and developed countries. We cannot exclude the effect of selection bias influencing our results and future surveys should be used to determine the number of endoscopic procedures in each country and then survey a proportional number of endoscopists throughout each country. On the other hand, the similarities between our results and the findings of single-nation or single-region reports are reassuring regarding the accuracy of our study results.3,5

For example, Swiss respondents in our survey reported that most of the endoscopies in Switzerland are performed with sedation, either a benzodiazepine/opioid or propofol. These findings are similar to the results of a nationwide survey of Swiss gastroenterologists, indicating that sedation is used for 77% and 78% of upper and lower endoscopies, respectively.3 Furthermore, all three Swiss respondents concurred that propofol use during the past five years had increased by at least 25%, compared to an increase of 30% between 1990 and 2003 reported in a nationwide survey.3 Similarly, there is concordance between the responses of European endoscopists in this survey and the results of two recent European studies on sedation practices.5,14

In summary, our results suggest that (1) a web-based survey can efficiently yield data regarding endoscopic practices on a world-wide scale, including from developing countries; (2) during the past 5 years, the use of sedation for endoscopy has increased in many countries, with unsedated procedures being the majority method in only a small proportion of countries represented in this survey; (3) a benzodiazepine/opioid combination remains the most common majority practice, although propofol use is rapidly gaining popularity; and (4) most practitioners represented in this survey adhere to published guidelines regarding intra-procedural monitoring. A global web-based survey of a larger number of practitioners (perhaps utilizing a database from a global endoscopy society) could further substantiate our findings. Data such as those reported here can help direct fellowship training and promote the dissemination of contemporary sedation techniques to developing nations.

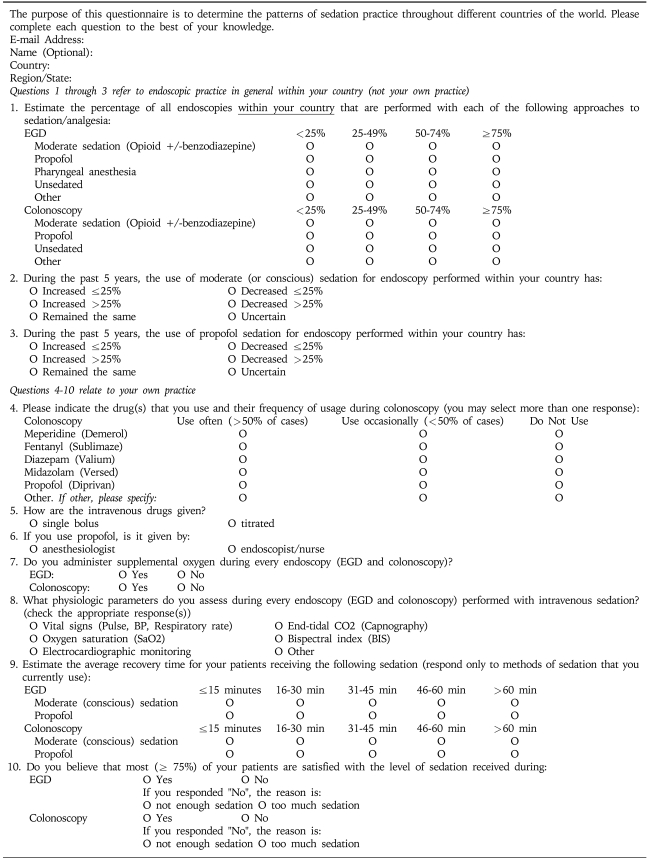

APPENDIX

An International Survey of Sedation and Monitoring Practice during Endoscopy

References

- 1.Cohen LB, Wecsler JS, Gaetano JN, et al. Endoscopic sedation in the United States: results from a nationwide survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:967–974. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aisenberg J, Brill JV, Ladabaum U, Cohen LB. Sedation for gastrointestinal endoscopy: new practices, new economics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:996–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heuss LT, Froehlich F, Beglinger C. Changing patterns of sedation and monitoring practice during endoscopy: results of a nationwide survey in Switzerland. Endoscopy. 2005;37:161–166. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faulx AL, Vela S, Das A, et al. The changing landscape of practice patterns regarding unsedated endoscopy and propofol use: A national Web survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Froehlich F, Harris JK, Wietlisbach V, et al. Current sedation and monitoring practice for colonoscopy: an International Observational Study (EPAGE) Endoscopy. 2006;38:461–469. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Data and Statistics: Country Groups. The World Bank. 2007. http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/DATASTATISTICS/0,,contentMDK:20421402~pagePK:64133150~piPK:64133175~theSitePK:239419,00.html.

- 7.Zubarik R, Ganguly E, Benway D, Ferrentino N, Moses P, Vecchio J. Procedure-related abdominal discomfort in patients undergoing colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3056–3061. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waye JD. Comment. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:411. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazzaroni M, Porro GB. Preparation, premedication, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2005;37:101–109. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell GD. Preparation, premedication, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2004;36:23–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowles CJ, Leicester R, Romaya C, Swarbrick E, Williams CB, Epstein O. A prospective study of colonoscopy practice in the UK today: are we adequately prepared for national colorectal cancer screening tomorrow? Gut. 2004;53:277–283. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.016436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campo R, Brullet E, Junquera F, et al. Sedation in digestive endoscopy. Results of a hospital survey in Catalonia (Spain) Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;27:503–507. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(03)70516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ristikankare MK, Julkunen RJ. Premedication for gastrointestinal endoscopy is a rare practice in Finland: a nationwide survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:204–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladas SD, Aabakken L, Rey JF, et al. Use of sedation for routine diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: an european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy survey of national endoscopy society members. Digestion. 2006;74:69–77. doi: 10.1159/000097466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]