Abstract

Background/Aims

Gallbladder (GB) polyps are commonly encountered in clinical practice, and are found more frequently as the number of medical screening examinations increases. The aim of this study was to determine optimal practice guideline for surgical treatment and follow-up of GB polyps.

Methods

Data from healthy subjects of Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) Health Care System of Gangnam Center were used to investigate the true prevalence of GB polyps. We also enrolled 689 patients with GB polyps diagnosed at SNUH from May 1st, 1988 to April 30th, 2006.

Results

The GB polyp prevalence was 6.1% (7.1% in males and 4.8% in females). The median follow-up duration in the 689 study patients was 60 months, and 139 (20%) of them had polyps ≥10 mm in size. Twenty-five of the 180 patients who underwent cholecystectomy had adenocarcinomas. The χ2 test was used to identify which of the following were risk factors of malignancy: age, sex, symptoms, size, rate of growth, multiplicity, accompanying stones, and shape. Age (≥57 years), presence of symptoms, size (≥10 mm), and shape (sessile) were found to be statistically significant risk factors by univariate analysis. However, multivariate analysis identified only age (≥57 years) and size (≥10 mm) as independent predictors of malignancy.

Conclusions

The present study shows that GB polyps ≥10 mm in size in patients aged ≥57 years are the independent factors predicting malignancy of the GB.

Keywords: Gallbladder, Polyp, Cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder (GB) may be defined as elevations on the GB mucosa. Such polypoid lesions affect 4-6% of the healthy adult population.1-4 Moreover, given the increasing use of abdominal ultrasonography (USG) in modern clinical practice, more polypoid lesions of the gallbladder are detected.5 Although most polyps are benign (usually cholesterol polyps), some early carcinomas of the GB resemble benign polyps,5 and the preoperative differential diagnosis of tumorous and non-tumorous polyps remains difficult. Furthermore, GB cancer is highly lethal with poor prognosis, and is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract. In fact, the only chance of cure comes from early detection and curative surgery. Therefore, the differentiation of precancerous lesions and earlier GB carcinoma originating from a GB polyp is essential for proper treatment.6-9 Currently, surgical removal is recommended for GB polyps sized >1 cm in view of the higher risk of malignancy,5,10-14 whereas patients with a smaller polyp usually require repeated USG and follow-up. It causes a certain degree of anxiety to the patient, and presents a considerable cost burden to the health care system.5 In addition, the study results are mainly from 1980 to 1990, and there are few studies who had follow-up duration long enough to help us to give information on natural courses of GB polyps. Therefore, we thought that it is very important to re-evaluate the risk factors in predicting malignancy from GB polyps, and to present evidence that aids decision making regarding forms of treatment, i.e., surgery or regular follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Epidemiology of GB polyps and patients enrollment

To investigate epidemiologic information of GB polyps without any selection bias, we used data from healthy subjects who attended SNUH Gangnam Center for a routine health examination from October 1st, 2003 to July 31st, 2005.

For the study patients, 689 newly diagnosed GB polyp patients at SNUH from Janurary 1st 1988 to April 30th 2006 were enrolled. Electronic medical records were thoroughly reviewed to get clinical and pathologic information, and following factors were evaluated in detail; age, sex, presence of symptoms, initial size, mass growth, mass multiplicity, accompanied stones, and shape. Patients were excluded if they had diseases capable of affecting survival, i.e., congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure, coronary heart disease, liver cirrhosis, malignancies, and others.

2. Diagnosis of GB polyp

Sonographic examinations were performed using an Acuson 128 (Acuson, Mountain View, CA) equipped with a 3.5/5.0 MHz ultrasound probe. All patients were fasted for at least 8 hours prior to USG. A standard sonography protocol was followed for all examinations. GB was imaged in longitudinal and transverse planes in the supine or left decubitus position (depending on body habits, bowel gas, and GB position). Field of view and transmission focusing were optimized for GB imaging in each case. In addition, standard sonographic criteria were used to diagnose GB polyps as follows: lesions had to be immobile, non-shadowing, hyperechoic compared to surrounding bile, and attached to the GB wall.15 Lesions that did not fulfill all of these criteria were not diagnosed as GB polyps. We tried to categorize subjects under USG into 5 different groups according to characteristics of USG findings that were documented by Okamoto's study in 1999,14 group A, no abnormal findings; group B, benign lesions such as polypoid lesion (diameter <5 mm), cornet-like echo, or GB swelling, which were followed-up once/yr; group C, benign lesions, such as polypoid lesion (5 mm ≤ diameter <10 mm), strong echo within the GB, or slight wall thickness of the GB, group D, benign lesion, but one in which malignancy could not be ruled out, such as polypoid lesion (diameter ≥10 mm), mass formation, debris, atrophic GB, or severe wall thickening of the GB, group E, suspected malignancy or malignancy, many of which were polypoid lesions with irregularity or heterogeneity, or with irregular wall thickness of the GB. In addition, we categorized shapes of GB in three different groups; papillary, sessile, and pedunculated polyps. Papillary polyps are the ones with papillary shape regardless of their size. Sessile polyp is nodular or lobulated mass with broad base, and a pedunculated polyp has narrow base compare to its height. The most important difference between the pedunculated polyp and papillary polyp is the presence of stalk beside the shape of main lesion.

The maximum diameters of polyps were measured using electronic calipers and rounded to the nearest millimeter. During USG follow-up, polyp size changes were defined as; decrement - a reduction in diameter >3 mm, increment - an increase in diameter of >3 mm, and no change - a measured diameter change of <3 mm.

3. Surgical resection in study patients and follow-up schedule

GB polyp patients underwent cholecystectomy if they were in following conditions; symptomatic group B & C patients with or without GB stone, group B & C patients who really want to undergo cholecystectomy due to anxiety even with doctor's assurances, and group D & E patients. Since, it was not possible to prove causal relation between symptoms and GB abnormalities, we defined symptomatic patients with either one of these findings (episodes of biliary colic, frequent vague gastric discomfort and dyspepsia without any abnormality in gastroduodenoscopy, right upper quadrant discomfort). In addition, we included increased size change in short term follow-up duration whose polyps are less than 10 mm. The first follow-up intervals from initial diagnosis were conducted at 3 or 6 months and second follow-up intervals were conducted at 6 or 12 months with USG.

4. Statistics

Statistical analyses of categorical variables were performed using Pearson's χ2 test or Fisher's exact test; two level continuous variables and three or more level continuous variables were compared by using the Student's t-test and by analysis of variance, respectively. Two sided p-values of <0.05 were considered significant. Multivariate analysis was performed using multiple logistic regression models. All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

1. Data from Health Care System Gangnam Center, SNUH

1) Prevalence of GB polyps in healthy subjects

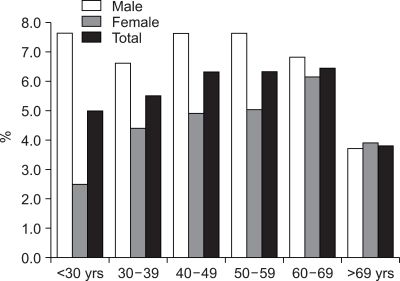

The total of 24,617 healthy subjects underwent abdominal USG at the SNUH Gangnam Center during the study period, and 954 of 13,328 (7.1%) men and 542 of 11,289 (4.8%) women had GB polyps, with an overall prevalence of 6.1% (1,496/24,617). Prevalence of GB polyp with respect to age is shown in Fig. 1, and a particularly high prevalence was found in those aged 40 to 70 years.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of GB polyps by age.

2. Data from study patients in SNUH

1) Characteristics of GB polyp and cholecystectomy

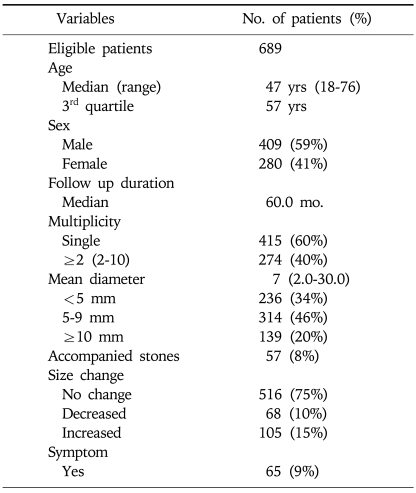

There were 689 eligible patients (M: 409, F: 280) of median age 47 years (range from 18 to 76 years), and these were followed for a median 60 months. Four-hundred five (60%) patients had a single polyp and 57 (8%) patients had accompanying GB stones. Mean diameter of GB polyps at initial diagnosis was 7 mm (range 2 to 30 mm). One-hundred nine (20%) patients with a GB polyp of >10 mm, and 516 (75%) patients never had size change of polyps. Sixty five (9%) patients had symptoms of mainly epigastric and right upper quadrant pain prior to the hospital visit (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of GB Polyps

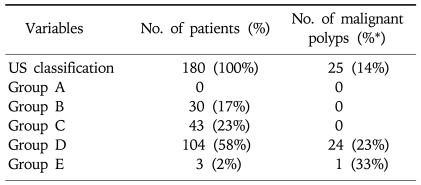

According to our practice guideline for cholecystectomy, 180 patients underwent surgical resection (Table 2). There were 35 group D patients who did not undergo cholecystectomy even they had GB polyp ≥10 mm; 30 patients had GB polyps with 10 mm, 2 patients with 11 mm, 1 patient with 13 mm, and 2 patients with 15 mm. Some of the patients had severe co-morbidities which might elevate the risk of cholecystectomy, and there were some patients who did not want to undergo cholecystectomy strongly even if they had chance to have malignant GB polyps. They underwent close monitoring with 3 months interval for a year and later were followed-up with 6 months of interval. The median follow-up duration without symptoms or signs that suggest malignancy was 72 months (29-91 months).

Table 2.

Characteristics of GB Polyps in Patients Who Underwent Cholecystectomy

*Percentage of malignant polyps from each group (A-E).

2) Characteristics of malignant GB polyps

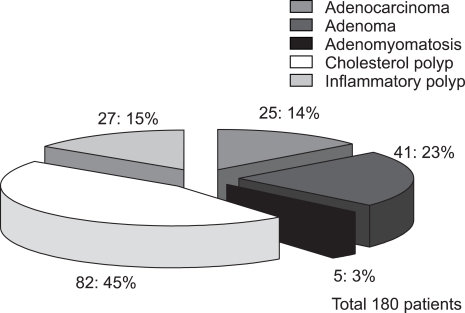

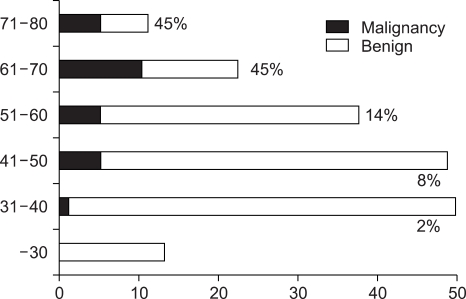

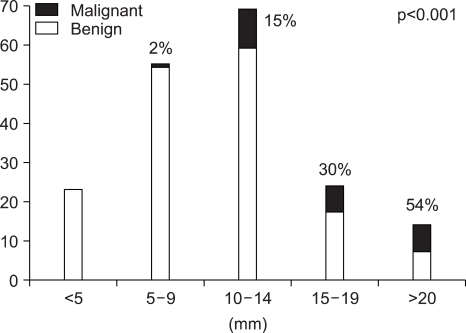

The pathologic results of 180 patients who underwent cholecystectomy are shown in Fig. 2. There were 25 (14%) adenocarcinomas, 41 (23%) adenomas, and 82 (45%) cholesterol polyps. The characteristics of malignant GB polyp are shown in Table 3. Median age of patients with malignant GB polys was 62 years, which was substantially older than that of all GB polyp patients (47 years). There were only two cases of malignant GB polyps with accompanying stones and 16 of 25 (64%) malignant GB polyps were in sessile shape. Pathologically, all malignant GB polyps were adenocarcinomas and 4 of the 25 malignant GB polyps occurred in adenoma background. Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 showed prevalence of GB polyps according to age and size. No malignant GB polyp was found in subjects younger than 30 year-old (Fig. 3). The distribution of malignant polyps by age was as follows: 1/49 (2%) in 31 to 40 year-old, 4/48 (8%) in 41 to 50 year-old, 5/37 (14%) in 51 to 60 year-old, 10/22 (45%) in 61 to 70 year-old, and 5/11 (45%) in 71 to 80 year-old. Distributions by size were; 17/91 (19%) sized 10-19 mm and 7/13 (54%) sized >20 mm. In contrast, only one (1/76) malignant GB polyp was less than 10 mm in size. Fig. 4B provides a further breakdown by size, i.e., 10/68 (15%) malignant GB polyps sized 10~14 mm, 7/23 (30%) sized 15-19 mm, and 7/13 (54%) larger than 20 mm in size.

Fig. 2.

Pathology of cholecystectomy cases.

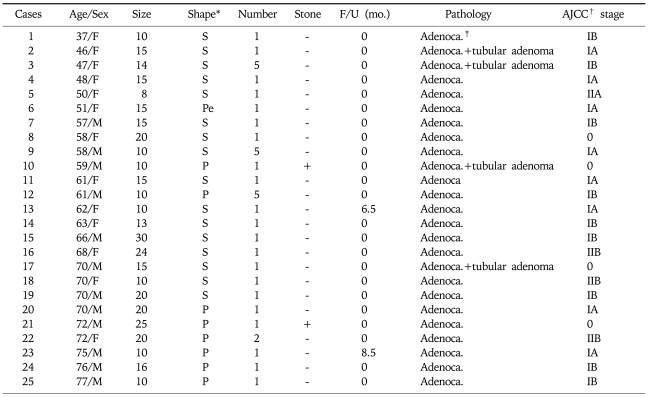

Table 3.

Characteristics of Malignant GB Polyps

*Shape; Sessile: S, Peduculated: Pe, Papillary: P.

†AJCC; American Joint Committee on Cancer.

‡Adenoca.; Adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of malignant GB polyps by age.

Fig. 4.

Prevalence of malignant GB polyps by size.

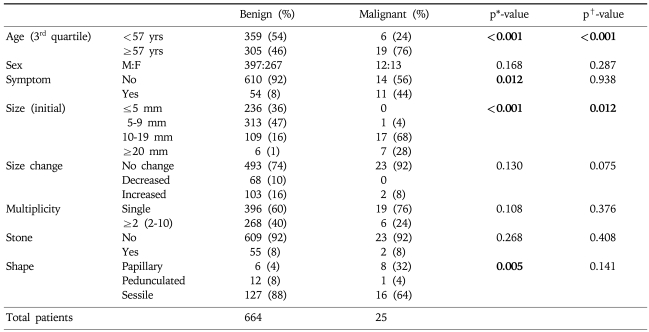

3) Benign versus malignant GB polyps and risk factor analysis

Table 4 shows benign and malignant GB polyps in terms of clinical and morphological characteristics. The prevalence of risk factors were investigated according to age, sex, presence of symptoms, initial size, size change, multiplicity, accompanying stones, and shape. Most malignant GB polyp patients occurred in the above 3rd quartile age group and the male to female ratio for all malignant polyps was 0.9 (12:13). In terms of polyp size, most benign polyps were <20 mm (94%) and usually <10 mm (84%). Moreover, most benign and malignant GB polyps showed no significant size change during follow-up and no accompanying stones. The Pearson's χ2 test was used to identify risk factors of malignancy in the 180 cholecystectomy cases. The factors analyzed were; age, sex, presence of symptoms, initial size, size progression rate, shape, multiplicity, and associated stones (Table 4). Of these, age (≥57 year-old), presence of symptoms, size (≥10 mm), and shape (sessile) were statistically significant risk factors by univariate analysis. However, multivariate analysis identified only age (≥57 year-old) and size (≥10 mm) as independent predictors of malignancy.

Table 4.

Benign vs Malignant GB Polyps and Risk Factor Analysis

*p value by chi-square test applied to 180 cholecystectomy cases.

†p-value by logistic Cox-regression test for 180 cholecystectomy cases.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the natural course of GB polyps and attempted to identify factors that would aid the surgery/regular follow-up decision making process. The main management concern is that malignant lesions be identified and treated at the earliest possible stage. Moreover, for such risk factors to be clinically useful, they should accurately predict the presence of malignant GB polyps and be easily evaluated. This means that we should be able to describe the characteristics of both benign and malignant GB polyps including premalignant lesions. In addition, the clinical implications of these factors should be determined, as this would allow more accurate prognosis, and thus benefit patients.

In a study by Csendes et al,16 an analysis of surgically treated patients with polyps <10 mm found no malignancy in all 27 cases. On the other hand, Terzi et al17 reported prevalence rate of malignancy among 100 GB polyp patients as 26%, and Kubota et al18 reported that as 22% among 72 patients. We considered that these large prevalence discrepancies were best explained by patient selection and inadequate sample size. However, two series recently conducted in Chinese populations reported a prevalence of 5.7% among 123 patients and 3.7% among 244 patients,19,20 which concur with the 3.6% of the present study.

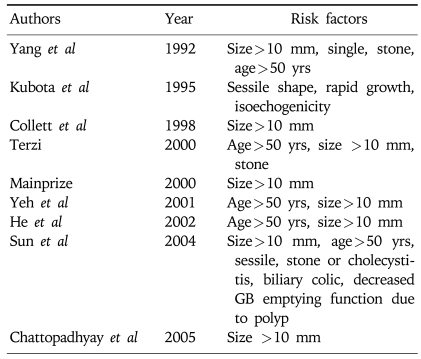

To differentiate malignant from benign polyps, we investigated and compared demographic factors (sex and age), clinical factors (symptom and accompanied GB stones), and morphology of GB polyps (i.e., size, size progression rate, shape, and multiplicity). This analysis identified age, the presence of symptoms, and initial polyp size and shape as statistically significant risk factors (Table 4). Several studies have sought to identify the risk factors of malignant GB polyps (Table 5).11-13,17-21 In addition, we analyzed the pathologic characteristics of cholecystectomy cases to determine whether there is any possibility of premalignant lesions of the malignant GB polyps (Fig. 2). It has been reported that the polyp-to-cancer sequences of colonic polyps is similar to that of GB adenoma,22 but other studies disagree. Eelkema et al23 evaluated 226 patients with a GB polyp by cholecystography; 113 of these patients were examined 15 years after initial diagnosis but no malignancy was observed. The authors suggested that cholecystographically demonstrated GB polyp without stones might be benign and remained benign. Therefore, they suggested that GB malignancy differed from colon cancer and colon adenoma in terms of its carcinoma sequence, and that the most important premalignant factor for GB polyps is accompanied GB stones. In the present study, there were 41 adenomas and 25 adenocarcinomas, and of the 25 malignant GB polyps, 4 had adenoma background. Moreover, had an adenoma to carcinoma sequence existed, the prevalence of adenoma should have been higher than that of malignancy, but the prevalence of GB adenoma is extremely low (none were found in the present study). Therefore, this should be further investigated. On the other hand, accompanying GB stones are a well known independent risk factor for malignancy in western countries.24-26 However, the presence of a GB stone was not found to be an independent risk factor for the presence of a malignant GB polyp in the present study (Table 4). This result implies that the presence of a GB stone is not a strong risk factor for GB cancer in the Korean population. In the present study, only 57 (8%) of 689 GB polyp patients had an accompanying GB stone and 2 of 25 malignant GB polyp patients had an accompanying GB stone. However, there are some limitations in our study. There are several studies that endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has improved accuracy of the differential diagnosis of GB polyps.6,7,9,27,28 Since this was a retrospective study, some of the patients underwent EUS and we could not evaluate as uniform diagnostic modalities. However, there are many common factors that could predict malignant GB polyps. Sugiyama et al reported that polypoid lesions exceeding 10 mm and sessile shape suggested malignancy.28 In addition, Sadamoto et al reported that size (>10 mm), heterogenous internal echo pattern and the absence of hyperechoic spots are suggesting factors of malignancy.6

Table 5.

Risk Factors Predicting Malignancy

Several studies have tried to identify predictors of malignant GB polyps for early detection of GB cancer. As summarized in Table 3, 25 malignant GB polyp patients revealed as early stage GB cancer (4: stage 0, 8: IA, 9: IB, 1: IIA, and 3: IIB). Usually, GB cancer is diagnosed in an advanced stage, when the prognosis for survival is less than 5 years in 90% of cases.26,29 Therefore, we should concentrate on finding useful and strong risk factors for malignant GB polyps that facilitate the early detection of GB cancer. Furthermore, it is important to discriminate between malignant and the benign polyps, and to utilize appropriate follow up schedules. If not, too much resource might be allocated to the monitoring of GB polyps on the one hand, or the early detection of GB cancer might be defective on the other. The present study shows that GB polyps with an age (≥57 year-old) and a size (≥10 mm) are the independent factors for predicting malignancy of GB. However, it might be helpful to consider other associated factors such as symptoms or sessile shape during careful monitoring of suspected patients.

References

- 1.Myers RP, Shaffer EA, Beck PL. Gallbladder polyps: epidemiology, natural history and management. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:187–194. doi: 10.1155/2002/787598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CY, Lu CL, Chang FY, Lee SD. Risk factors for gallbladder polyps in the Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2066–2068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segawa K, Arisawa T, Niwa Y, et al. Prevalence of gallbladder polyps among apparently healthy Japanese: ultrasonographic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:630–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jorgensen T, Jensen KH. Polyps in the gallbladder. A prevalence study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1990;25:281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee KF, Wong J, Li JC, Lai PB. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Am J Surg. 2004;188:186–190. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadamoto Y, Oda S, Tanaka M, et al. An useful approach to the differential diagnosis of small polypoid lesions of the gallbladder, utilizing an endoscopic ultrasound scoring system. Endoscopy. 2002;34:959–965. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azuma T, Yoshikawa T, Araida T, Takasaki K. Differential diagnosis of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder by endoscopic ultrasonography. Am J Surg. 2001;181:65–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi WB, Lee SK, Kim MH, et al. A new strategy to predict the neoplastic polyps of the gallbladder based on a scoring system using EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:372–379. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sugiyama M, Xie XY, Atomi Y, Saito M. Differential diagnosis of small polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: the value of endoscopic ultrasonography. Ann Surg. 1999;229:498–504. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chattopadhyay D, Lochan R, Balupuri S, Gopinath BR, Wynne KS. Outcome of gall bladder polypoidal lesions detected by transabdominal ultrasound scanning: a nine year experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2171–2173. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i14.2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun XJ, Shi JS, Han Y, Wang JS, Ren H. Diagnosis and treatment of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: report of 194 cases. Hepatobil Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3:591–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mainprize KS, Gould SW, Gilbert JM. Surgical management of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder. Br J Surg. 2000;87:414–417. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collett JA, Allan RB, Chisholm RJ, Wilson IR, Burt MJ, Chapman BA. Gallbladder polyps: prospective study. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:207–211. doi: 10.7863/jum.1998.17.4.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto M, Okamoto H, Kitahara F, et al. Ultrasonographic evidence of association of polyps and stones with gallbladder cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:446–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.875_d.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lichtenstein JE. The gallbladder: what if it's not stone disease? Semin Roentgenol. 1991;26:209–215. doi: 10.1016/0037-198x(91)90015-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csendes A, Burgos AM, Csendes P, Smok G, Rojas J. Late follow-up of polypoid lesions of the gallbladder smaller than 10 mm. Ann Surg. 2001;234:657–660. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terzi C, Sokmen S, Seckin S, Albayrak L, Ugurlu M. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: report of 100 cases with special reference to operative indications. Surgery. 2000;127:622–627. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.105870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubota K, Bandai Y, Noie T, Ishizaki Y, Teruya M, Makuuchi M. How should polypoid lesions of the gallbladder be treated in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surgery. 1995;117:481–487. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80245-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He ZM, Hu XQ, Zhou ZX. Considerations on indications for surgery in patients with polypoid lesion of the gallbladder. Di Yi Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2002;22:951–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh CN, Jan YY, Chao TC, Chen MF. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: a clinicopathologic study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang HL, Sun YG, Wang Z. Polypoid lesions of the gallbladder: diagnosis and indications for surgery. Br J Surg. 1992;79:227–229. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldridge MC, Bismuth H. Gallbladder cancer: the polyp-cancer sequence. Br J Surg. 1990;77:363–364. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eelkema HH, Hodgson JR, Stauffer MH. Fifteen-year follow-up of polypoid lesions of the gall bladder diagnosed by cholecystography. Gastroenterology. 1962;42:144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Misra MC, Guleria S. Management of cancer gallbladder found as a surprise on a resected gallbladder specimen. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:690–698. doi: 10.1002/jso.20537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. New Engl J Med. 1999;341:1368–1378. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C. Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1591–1602. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akatsu T, Aiura K, Shimazu M, et al. Can endoscopic ultrasonography differentiate nonneoplastic from neoplastic gallbladder polyps? Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:416–421. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Yamato T. Endoscopic ultrasonography for differential diagnosis of polypoid gall bladder lesions: analysis in surgical and follow up series. Gut. 2000;46:250–254. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.2.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]