Abstract

Background/Aims

Several simple tests for hepatic fibrosis employ indirect markers. However, the efficacy of using direct and indirect serum markers to predict significant fibrosis in clinical practice is inconclusive. We analyzed the efficacy of a previously reported indirect marker of hepatic fibrosis - the aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) - in patients with nonalcoholic chronic liver diseases (CLDs).

Methods

A total of 134 patients who underwent a percutaneous liver biopsy with a final diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B (n=93), chronic hepatitis C (n=18), or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (n=23) were enrolled. A single-blinded pathologist staged fibrosis from F0 to F4 according to the METAVIR system, with significant hepatic fibrosis defined as a METAVIR fibrosis score of ≥2.

Results

The mean area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of APRI for predicting significant fibrosis in nonalcoholic CLDs was 0.84 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.78-0.91]. APRI yielded the highest mean AUROC in the patients with chronic hepatitis B (0.85; 95% CI, 0.771-0.926). The positive predictive value of APRI ≥1.5 for predicting significant fibrosis was 89%. The negative predictive value of APRI <0.5 for excluding significant fibrosis was 80%.

Conclusions

APRI might be a simple and noninvasive index for predicting significant fibrosis in nonalcoholic CLDs.

Keywords: Aspartate aminotransferase, Fibrosis, Hepatitis B

INTRODUCTION

Performing a liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for assessing the severity of hepatic fibrosis and guiding the therapeutic decision. However, a liver biopsy has several limitations, such as morbidity, mortality,1,2 sampling error3-7 resulting from patchy distribution of hepatic fibrosis, reluctance of patients to receive repeat biopsies, and interobserver variation.4,5 Furthermore, a liver biopsy provides only static information that does not reflect the balance between fibrogenesis and fibrolysis.8

Hepatic fibrosis is associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and degradation, and hence is a dynamic process.8-10 Recent improvements in the understanding of the pathophysiology of ECM metabolism have made it necessary to develop approaches for evaluating of hepatic fibrosis of chronic liver diseases (CLDs) that are noninvasive, rapid, and easy to apply. Several simple tests have employed indirect markers of hepatic fibrosis, including the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio (AAR),11-15 cirrhosis discriminant score,16 age-platelet index (API),17 Pohl score,18 and the AST to platelet ratio index (APRI).19 However, currently there is no definitive algorithm for determining the most appropriate indirect marker of hepatic fibrosis or how to practically implement these tests.4

Millions of patients worldwide suffer from CLDs that progress to cirrhosis or hepatoma. The incidence of hepatoma in South Korea is 44.95 and 11.96 cases per 100,000 person-years in men and women, respectively, with 74.2% of these patients having hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections and 8.6% having hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections.20 Considering that CLDs generally progress to cirrhosis because of longstanding repetition of the inflammation and healing process independent of underlying diseases, the usefulness of these tests in various etiologies of CLDs including chronic hepatitis B (CHB), chronic hepatitis C (CHC), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) needs to be assessed. However, to the best of our knowledge, most investigations of indirect fibrosis markers have involved only patients with CHC, with few studies being related to CHB.21-24

We hypothesized that indirect markers for hepatic fibrosis can significantly predict this condition regardless of its etiologies. We therefore analyzed APRI, API, AAR, and the platelet count in patients with CHB, CHC, and NAFLD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective study of 189 consecutive patients who underwent a percutaneous liver biopsy at Hallym University Sacred Hospital from January 2001 to December 2005 with a final diagnosis of CHB, CHC, or NAFLD. We performed a baseline liver biopsy before antiviral treatment or recommended a liver biopsy to guide the treatment decision in patients with CHB and CHC. In presumed NAFLD, a liver biopsy was performed as a diagnostic or staging test. CHB was diagnosed by the presence of HBV surface antigens for at least 6 months with appropriate biopsy findings, and CHC patients tested positive for the presence of HCV RNA using a polymerase chain reaction assay. NAFLD was defined as the presence of macrovascular steatosis, the absence of significant ethanol exposure, and negative virology results. NAFLD ranged from simple steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with inflammation, fibrosis, ballooning, or Mallory bodies at biopsies. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) additional metabolic or vascular causes of CLD or coinfection with hepatitis D, (2) clinically overt cirrhosis based on ultrasonography and/or esophagogastroduodenoscopy, (3) antiviral treatment before liver biopsy, and (4) alcohol consumption exceeding 20 g per day in men and exceeding 10 g per day in women. Fifty-five of the 189 consecutive patients were excluded because their biopsy specimens had fewer than six portal fields, and hence 134 patients were included in the analysis.

Liver tissue was obtained by a sonography-guided percutaneous biopsy using a Tru-Cut needle (ACECUT®, Automatic Biopsy System, 18 gauge, 22-mm type, Japan) and stained with hematoxylin-eosin-safran and Masson's trichrome. A single-blinded pathologist staged fibrosis of CLDs from F0 to F4 on the METAVIR system.25 In accordance with the practice guidelines recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, we defined significant hepatic fibrosis as a METAVIR fibrosis score of ≥2. AST, ALT, and platelet biochemical tests were performed on or 1 day before the day of the liver biopsy, from which we calculated APRI, API, and AAR.

Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 11.5, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Bivariate Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation between variables. We compared the mean values of simple indices between the significant-fibrosis group (F0/F1) and the insignificant-fibrosis group (F2-F4). We also discriminated advanced fibrosis (F0-F2 vs. F3/F4) and cirrhosis (F0-F3 vs. F4). We analyzed the power of detecting significant fibrosis based on the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), with an AUROC of 0.85-0.95 considered an indirect fibrosis marker of significant fibrosis.4 Finally, we also assessed the usefulness of indirect markers based on the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

RESULTS

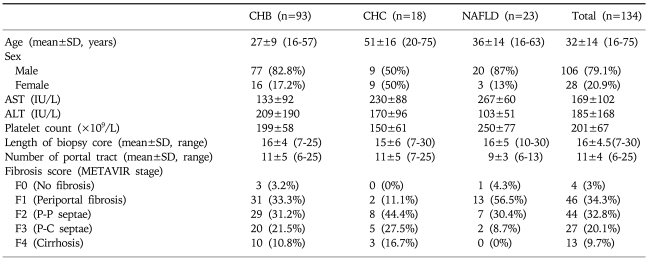

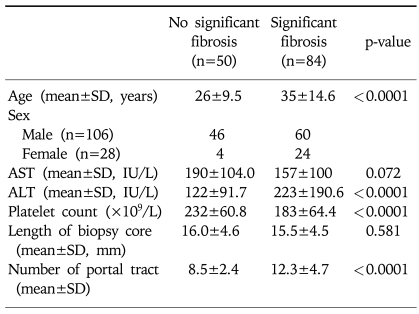

The 134 patients comprised 93 with CHB, 18 with CHC, and 23 with NAFLD. Their mean age was 32 years, and 20.9% of them were female. The mean age, ALT, and number of portal tracts in biopsy specimens were higher and the platelet count was lower in patients with F2-F4 fibrosis than in those with F0/F1 fibrosis, whereas AST and the mean length of the biopsy core did not differ between these two groups. Significant fibrosis was present in 63.5%, 88.9%, and 39.1% of the patients with CHB, CHC, and NAFLD, respectively. Other clinical and laboratory data of the 134 patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 134 Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

P-P, portal-portal; P-C, portal-central; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; CHC, chronic hepatitis C; NAFLD, non alcoholic fatty liver disease; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 134 Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

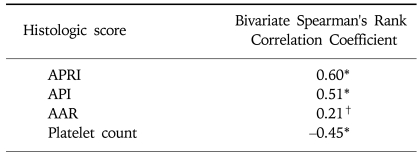

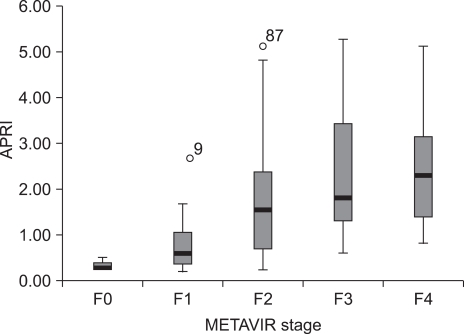

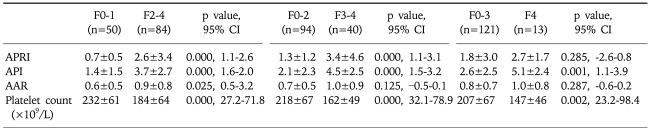

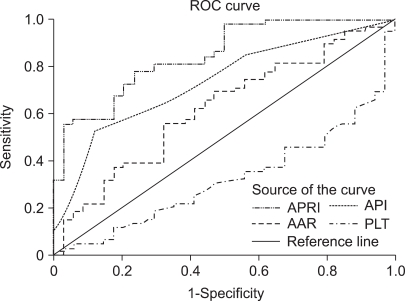

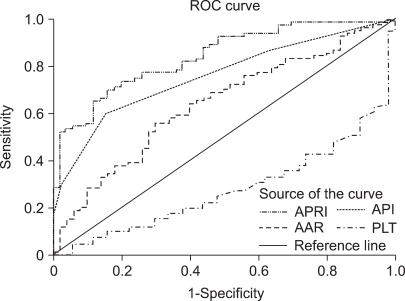

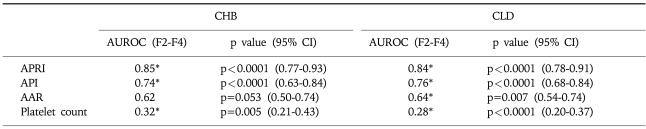

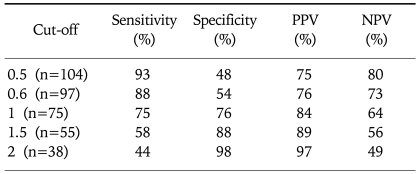

Hepatic fibrosis was moderately correlated with APRI [correlation coefficient (γ)=0.6] and API (γ=0.51), weakly correlated with AAR (γ=0.21), and negatively correlated with the platelet count (γ=-0.45; Table 3). Of the four indices, APRI exhibited the highest bivariate Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (γ=0.6). The mean values of APRI [p<0.0001; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.113-2.633; Fig. 1], API (p<0.0001; 95% CI, 1.599-2.038), AAR (p=0.025; 95% CI, 0.462-3.220), and platelet count (p<0.0001; 95% CI, 27.23-71.83) differed significantly between the F0/F1 and F2-F4 groups by t-test. However, the mean values of APRI and AAR did not differ between F0-F3 and F4 (p=0.285 and p=0.287, respectively; Table 4). Receiver operating characteristic curves of APRI, API, AAR, and the platelet count for predicting the presence of significant fibrosis in CHB and CLDs are presented in Fig. 2 and 3. APRI yielded the highest AUROC for predicting significant fibrosis in the patients with CHB (mean, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.771-0.926). The mean AUROCs of API and the platelet count were 0.74 (p<0.0001; 95% CI, 0.63-0.84) and 0.32 (p=0.005; 95% CI, 0.21-0.43) in patients with CHB, respectively. However, the mean AUROC of AAR of 0.62 did not differ significantly from a value of 0.5 (p=0.053; Table 5). In CLDs, the mean AUROCs of APRI, API, AAR, and the platelet count were 0.84, 0.76, 0.64, and 0.28, respectively (Table 5). The PPV of APRI ≥1.5 for predicting significant fibrosis was 89% in 41% of patients. The NPV of APRI<0.5 for excluding significant fibrosis was 80% in 22.4% of patients. An APRI of ≥2.0 had the highest specificity (98%) and PPV (97%). An APRI of (0.5 had a sensitivity of 93% and an NPV of 80% for predicting significant fibrosis (Table 6).

Table 3.

Correlation of Histologic Stage with Simple Fibrosis Tests

*p<0.01.

†p<0.05.

APRI, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index; API, age-platelet index; AAR, AST/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio.

Fig. 1.

Relationship between APRI and stage of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic CLD.

Table 4.

Comparison of the Mean Values of Simple Fibrosis Tests

METAVIR stage: F0, no fibrosis; F1, periportal fibrosis; F2, portal-portal septae; F3, portal-central septae; F4, cirrhosis; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval of the difference; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index; API, age-platelet index; AAR, AST/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio

Data are mean±standard deviations unless otherwise indicated.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of simple fibrosis tests for predicting significant fibrosis in patients with CHB.

Fig. 3.

ROC curves of simple fibrosis tests for predicting significant fibrosis in patients with CLDs.

Table 5.

Diagnostic Power of Simple Fibrosis Tests for Prediction of Significant Fibrosis (F2-F4)

*p<0.05 vs. AUROC 0.5.

CHB, chronic hepatitis B; CLD, chronic liver disease; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; APRI, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index; API, age-platelet index; AAR, AST/alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio.

Table 6.

Diagnostic Accuracies of APRI for Predicting Significant Fibrosis

APRI, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

DISCUSSION

Of the four indirect fibrosis markers considered in this study, APRI was the most accurate simple marker for predicting significant hepatic fibrosis in various etiologies of CLDs, especially in CHB, though API and the platelet count were also good indirect markers. Whilst a liver biopsy has been considered the gold standard for assessing the severity of hepatic fibrosis and guiding the therapeutic decision, it has several limitations such as invasiveness and sampling error. Indeed, 55 of the 189 original cases (29%) in this study were excluded because of inadequate biopsy samples. The PPV of APRI ≥1.5 for predicting significant fibrosis was 89% in 41% of our patients, which is as reliable as that reported previously for patients with CHC.19,26 The NPV of APRI <0.5 for excluding significant fibrosis was 80% in 22.4% of patients, which was somewhat lower than that reported by Wai et al.19 but similar to that reported by Lackner et al.26 However, considering the PPV and NPV of APRI, clinicians should keep in mind the rates of false positives and negatives of APRI when applying it at the bedside.

Interestingly, the prevalence of significant fibrosis was higher in this study (63%) than that found by Wai et al.19,24 (47% and 48%) and Lackner et al.26 (50%). Although this high prevalence of advanced fibrosis in our study population could have overestimated PPV, we strictly excluded patients with overt cirrhosis based on ultrasonography and esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Therefore, we consider our AUROC of more than 0.85 for predicting significant fibrosis using APRI to be very meaningful, even though Wai et al.24 reported a lower accuracy of APRI for predicting significant fibrosis (mean AUROC, 0.63) in CHB, and suggested that the pathogenesis of progression of hepatic fibrosis differs between CHB and CHC.

Markers that reflect alterations in hepatic function, such as the PGA index, Fibrotest®, and APRI, are defined as indirect markers, while markers that directly reflect ECM metabolism are defined as direct markers of fibrosis. Most previous studies of simple fibrosis markers involved patients with CHC, and the role of these serum markers in clinical practice is inconclusive.9 Especially, a multicenter trial found that APRI showed a low sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing significant fibrosis in patients with CHB24 and alcoholic liver disease.27 The necessity of investigating more diverse diseases such as CHB prompted the present study. A recent international multicenter cohort study showed that the accuracy of algorithms using various direct serum markers of fibrosis was similar to that of an expert liver pathologist, suggesting their usefulness in the assessment of CLDs.28 However, none of these direct markers are liver-specific, and they are expensive. In contrast, APRI is obtained from two routinely examined parameters (AST and the platelet count), and hence is a simpler and easier to apply index than other indices such as the Fibrotest® and Forn's index in clinical settings.

In this study, AAR was weakly correlated with fibrosis, with the AUROC of AAR being 0.62 in patients with CHB (and not differing significantly from a value of 0.5), despite some studies finding that AAR was a more accurate indirect marker for predicting cirrhosis.11,15 This discrepancy could be related to the use of different fibrosis scoring systems and study populations, with that latter being more likely considering that the results of our study using the METAVIR system (for which the kappa value is reportedly 0.64 in Korea29) were similar to those of Wai et al.19 and Lackner et al.26 using the Ishak system (e.g., alcoholic vs. nonalcoholic, significant fibrosis vs. cirrhosis).

This study has some limitations. First, the potential for selection bias cannot be excluded because the fibrosis score distribution varies with the etiology of CLDs, although we did enroll consecutive patients who received a liver biopsy between 2001 and 2005. Second, we compared the serum markers characterizing dynamic processes with percutaneous liver biopsy findings that represent the state of fibrosis at a certain point in time in only a small portion of the liver. Third, the changes in these indices resulting from histological changes with or without treatment were not assessed. Therefore, future studies should investigate whether simple indirect markers can reflect histologic changes with or without treatment and are suitable for use in clinical practice.

In conclusion, APRI might be a simple and noninvasive index for predicting significant fibrosis in various etiologies of CLDs including CHB.

References

- 1.Little AF, Ferris JV, Dodd GD, 3rd, et al. Image-guided percutaneous hepatic biopsy: effect of ascites on the complication rate. Radiology. 1996;199:79–83. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.1.8633176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindor KD, Bru C, Jorgensen RA, et al. The role of ultrasonography and automatic-needle biopsy in outpatient percutaneous liver biopsy. Hepatology. 1996;23:1079–1083. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afdhal NH, Nunes D. Evaluation of liver fibrosis: a concise review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1160–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, et al. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2614–2618. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedossa P, Dargere D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.hep.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pagliaro L, Rinaldi F, Craxi A, et al. Percutaneous blind biopsy versus laparoscopy with guided biopsy in diagnosis of cirrhosis. A prospective, randomized trial. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:39–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01393359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinzani M, Rombouts K, Colagrande S. Fibrosis in chronic liver diseases: diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2005;42(Suppl 1):S22–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis - from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38(Suppl 1):S38–S53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00429-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmet VJ, Roskams T. Cirrhosis reversal: a duel between dogma and myth. J Hepatol. 2004;40:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams AL, Hoofnagle JH. Ratio of serum aspartate to alanine aminotransferase in chronic hepatitis: relationship to cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:734–739. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheth SG, Flamm SL, Gordon FD, et al. AST/ALT ratio predicts cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.044_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park GJ, Lin BP, Ngu MC, et al. Aspartate aminotransferase: alanine aminotransferase ratio in chronic hepatitis C infection: is it a useful predictor of cirrhosis? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:386–390. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imperiale TF, Said AT, Cummings OW, et al. Need for validation of clinical decision aids: use of the AST/ALT ratio in predicting cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2328–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giannini E, Risso D, Botta F, et al. Validity and clinical utility of the aspartate aminotransferase-alanine aminotransferase ratio in assessing disease severity and prognosis in patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:218–224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonacini M, Hadi G, Govindarajan S, et al. Utility of a discriminant score for diagnosing advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1302–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poynard T, Bedossa P. Age and platelet count: a simple index for predicting the presence of histological lesions in patients with antibodies to hepatitis C virus. METAVIR and CLINIVIR cooperative study groups. J Viral Hepat. 1997;4:199–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.1997.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pohl A, Behling C, Oliver D, et al. Serum aminotransferase levels and platelet counts as predictors of degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3142–3146. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, et al. A simple non-invasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518–526. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheon JH, Park JW, Park KW, et al. The clinical report of 1,078 cases of hepatocellular carcinomas: National Cancer Center experience. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10:288–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebensztejn DM, Skiba E, Sobaniec-Lotowska M, et al. A simple noninvasive index (APRI) predicts advanced liver fibrosis in children with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2005;41:1434–1435. doi: 10.1002/hep.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers RP, Tainturier MH, Ratziu V, et al. Prediction of liver histological lesions with biochemical markers in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2003;39:222–230. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sim SJ, Cheong JY, Cho SW, et al. Efficacy of AST to platelet ratio index in predicting severe hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis in chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;45:340–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wai CT, Cheng CL, Wee A, et al. Non-invasive models for predicting histology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2006;26:666–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289–293. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lackner C, Struber G, Liegl B, et al. Comparison and validation of simple noninvasive tests for prediction of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2005;41:1376–1382. doi: 10.1002/hep.20717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lieber CS, Weiss DG, Morgan TR, et al. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index in patients with alcoholic liver fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1500–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg WM, Voelker M, Thiel R, et al. European Liver Fibrosis Group. Serum markers detect the presence of liver fibrosis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1704–1713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park YN, Kim HG, Chon CY, et al. Histological Grading and Staging of Chronic Hepatitis Standardized Guideline Proposed by the Korean Study Group for the Pathology of Digestive Diseases. Korean J Pathol. 1999;33:337–346. [Google Scholar]