Abstract

Background/Aims

Subcellular localization of hepatitis B virus (HBV) core antigen (HBcAg) and HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) is known to be related to the activity of liver disease and the level of HBV replication. The aim of this study was to determine the correlation between histologic activity, viral replication, and the intracellular distributions of HBcAg and HBsAg.

Methods

We enrolled 670 patients with chronic hepatitis B who underwent liver biopsy at Bundang CHA hospital between 1997 to 2007. The data from medical records were reviewed retrospectively.

Results

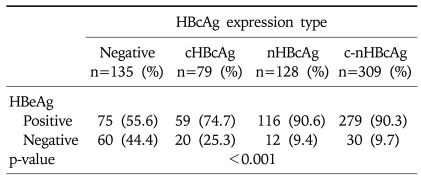

The stage of fibrosis was higher (3.31±1.34 vs. 2.43±1.39, mean±SD, p<0.01) and the grade of necroinflammatory activity was higher (9.39±3.11 vs. 6.13±3.40, p<0.001) for the cytoplasmic expression of HBcAg (cHBcAg) than for the nuclear expression of HBcAg (nHBcAg). The serum HBV DNA level was 677.30±983.14 pg/mL in cHBcAg, 1274.46±1417.28 pg/mL in nHBcAg, 1121.01±1121.0 pg/mL in c-nHBcAg, and 229.47±678.92 pg/mL in negative (p<0.001). HBeAg was seropositive in 74.7% of patients with cHBcAg, 90.6% in those with nHBcAg, 90.3% in those with n-cHBcAg, and 55.6% in those with negative (p<0.001). The histologic stage and grade of hepatitis were not significantly correlated with the subcellular localization of intrahepatic HBsAg (p>0.05).

Conclusions

These observations suggest that the histologic activity of hepatitis is higher and viral replication is lower in cHBcAg positive patients than in those with nHBcAg.

Keywords: HBcAg, HBsAg, Necroinflammatory stage, Fibrosis, Virus replication

INTRODUCTION

Indicators for the proliferation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) include serum HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), e antigen (HBeAg), HBV DNA, HBV DNA polymerase and HBV core antigen (HBcAg). It is known that there is a close relationship between these indicators.1-4

Among them, HBcAg plays a role as the major antigen for viral immune responses. It can be histologically classified into cHBcAg (cytoplasmic expression), nHBcAg (nuclear expression) and c-nHBcAg (both cytoplasmic and nuclear expression). This classification of HBcAg within the hepatocytes is associated with the degree of inflammatory responses, the severity of liver cell damage and the expression of HBeAg.5,6 In addition, HBsAg is histologically identified as cHBsAg (cytoplasmic expression), mHBsAg (membranous expression). It is known to be related to the activity of viral replication.7,8

Previous studies have shown that hepatocellular histologic activity of HBV patients was more severe in cases where HBcAg was expressed in the cytoplasm than those where it was expressed within the nucleus. The viral proliferation was less active in patients with cytoplasmic expression of HBcAg. In the case of HBsAg, the viral proliferation was more active in patients with membronous expression of HBsAg.3,7,9-11 However, these studies have such an insufficient number of patients as to generalize their results. Moreover, controversial opinions existed regarding this subject in some studies.12-14 Given this background, in 670 patients with chronic HBV hepatitis in whom the liver biopsy was performed at a single institution during the past 10-year period, we examined the correlations between histopathologic findings and the intracellular expression of HBcAg and HBsAg. We also examined the expression of viral proliferative markers such as HBV DNA and HBeAg, in accordance with the intracellular expression of HBcAg and HBsAg.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective chart review was conducted between March 1997 and March 2007. Of 871 cases in which liver biopsy was performed at Bundang CHA hospital following the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B, the following cases were excluded: (1) autoimmune hepatitis, (2) Wilson's disease, (3) primary biliary cirrhosis, (4) the positive of antibody to hepatitis C virus, (5) toxic hepatitis, (6) alcoholism, (7) a past history of the use of antiviral agents. We finally enrolled 670 patients in the current study.

The present study was conducted with a retrospective analysis of medical records. Immunohistochemical staining for HBsAg and HBcAg within the hepatocytes was done using commercially available DAKO Emvision Kit (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Cases in which HBsAg was expressed in cytoplasm were regarded as cHBsAg positive and those in which HBsAg is expressed in cell membrane only were regarded as having mHBsAg. Cases in which HBcAg was expressed in cytoplasm only were regarded as cHBcAg positive, where as those in which HBcAg is expressed in nucleus only were regarded as having nHBcAg, and those in which HBcAg is expressed in both cytoplasm and nucleus were regarded as c-nHBcAg positive. All the cases in which HBcAg positive group were classified into focal type and diffuse type according to the type of expression of intracellular HBcAg.

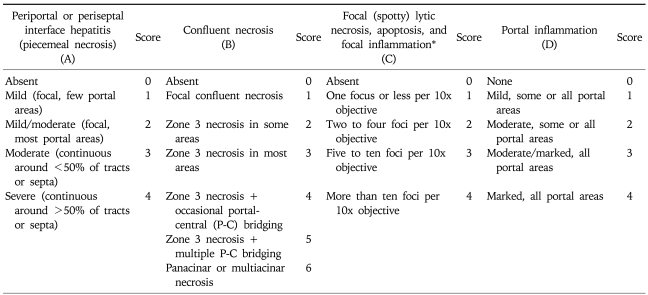

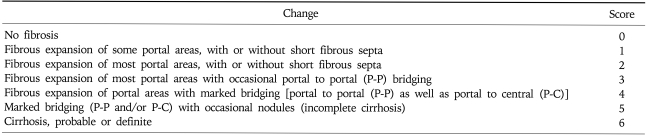

Using a light microscope, based on the modified hepatitis activity index (HAI), the histologic grade was evaluated.15 In addition, the histological staging was determined based on the modified stage.15 For grading, in each of four categories including piecemeal necrosis (A), confluent necrosis (or bridging necrosis) (B), focal lytic necrosis (C) and portal inflammation (D), scores were added and then classified as 0-18 (Table 1). The stage was classified as 0-6 based on the modified staging system by observing the degree of fibrosis on Gomori's silver impregnation stain and Masson's trichrome stain (Table 2).

Table 1.

Modified HAI Grading: Necroinflammatory Scores

HAI, hepatitis activity index.

*Does not include diffuse sinusoidal infiltration by inflammatory cells.

Table 2.

Modified Staging: Architectural Changes, Fibrosis, and Cirrhosis*

*Additional features which should be noted but not scored: intra-acinar fibrosis, perivenular ('chicken wire' fibrosis) and phlebosclerosis of terminal hepatic venules.

In the course of study, based on immunohistochemistry, two pathology specialists interpreted the intracellular distribution of HBsAg and HBcAg and the staging and grading under the guidance of light microscopy.

Results of a quantitative analysis of serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin, total protein, albumin, HBeAg and HBV DNA, which were performed just prior to a histopathologic analysis, were evaluated based on the expression of HBcAg and HBsAg.

All the statistics were analyzed using SPSS 11.5 (version 11.5 for window). Using a Chi-square test, a comparative analysis was performed to assess the correlation between the intracellular expression of HBsAg and HBcAg and the histopathologic stage. In regard to histologic grades, the differences in scores obtained from each category as well as the total scores between the groups were analyzed using one way ANOVA test. In addition, the differences in mean values of serum HBV DNA quantification, AST, ALT, total bilirubin, total protein albumin between the groups were analyzed using one way ANOVA test. An inter-group analysis was done using a crosstabulation test for the expression rate of HBeAg. Following statistical analysis, a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

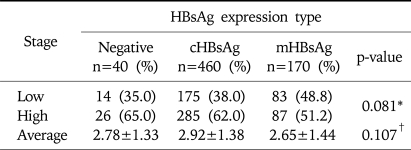

1. Correlation between histologic activity of hepatitis and intracellular expression of HBsAg

The number of HBsAg expression and HBsAg negative expression cases was 630 and 40, respectively, where the positive rate of HBsAg was 94%. The number of cHBsAg, mHBsAg, and HBsAg negative expression cases was 460, 170 and 40, respectively. There was no significant difference of the distribution of histopathologic stage between the groups (p=0.081, Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of Histologic Stage according to Intrahepatic HBsAg Expression

Low stage, stage 0-2; High stage, stage 3-6.

*Statistical significances were tested by Chi-square test.

†Statistical significances were tested by one-way ANOVA.

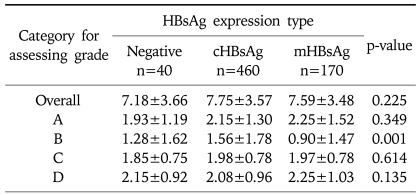

In each group, mean stage was 2.92±1.38 in the cHBsAg expression group, 2.65±1.44 in the mHBsAg expression group, and 2.78±1.33 in the HBsAg negative group. This showed that the stage was higher in the cHBsAg expression group than in the mHBsAg expression group. However there was no statistical significance (p=0.107, Table 3). Mean value of necro-inflammatory grad in each group was 7.75±3.57 in the cHBsAg expression group, 7.59±3.48 in the mHBsAg expression group, and 7.18 in the HBsAg negative group. This difference also did not show a statistical significance (p=0.225, Table 4).

Table 4.

Average Necroinflammatory Grade according to Intrahepatic HBsAg Expression

Statistical significances were tested by one-way ANOVA., Values are Mean±SD.

A, periportal or periseptal interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis); B, confluent necrosis; C, focal (spotty) lytic necrosis, apoptosis, and focal inflammation; D, portal inflammation.

2. Correlation between histologic activity of hepatitis and intracellular expression of HBcAg

1) Differences in the stages of hepatic tissue according to intracellular expression of HBcAg

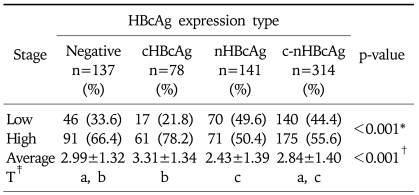

The number of HBcAg expression cases and HBcAg negative cases was 533 and 137, where the positive rate for HBcAg was 79.6%. HBcAg expression cases comprised 78 cHBcAg expression, 141 nHBcAg expression and 314 c-nHBcAg expression. There was a significant correlation between the intracellular distribution of HBcAg and the histopathologic stage (p<0.001, Table 5). In 78.2% of the cHBcAg expression group, the stage was higher than 3. In 50.4% of nHBcAg expression group, it was higher than 3. This showed that the stage was higher in the cHBcAg expression group than that of the nHBcAg expression group (p<0.001, Table 5, Fig. 1).

Table 5.

Distribution of Histologic Stage according to Intrahepatic HBcAg Expression

Low stage, stage 0-2; High stage, stage 3-6.

*Statistical significances were tested by Chi-square test.

†Statistical significances were tested by one-way ANOVA.

‡The same letters indicate insignificant difference between groups based on Tukey's multiple comparison test.

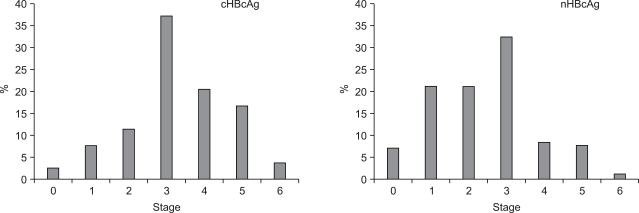

Fig. 1.

Distributions of cHBcAg and nHBcAg according to histologic stage. The histologic stage was much higher in the cHBcAg group than in the nHBcAg group.

The mean value of the histopatholologic stage was 3.31±1.34 in the cHBcAg expression group, 2.43±1.39 in the nHBcAg expression group, 2.84±1.40 in the c-nHBcAg expression group and 2.99±1.32 in the HBcAg negative group. The highest value was seen in the cHBcAg expression group. This was followed by the HBcAg negative group, the c-nHBcAg expression group and the nHBcAg expression group in the corresponding order. A post-hoc analysis based on Scheff's multiple comparison test showed a statistical significance in the difference between cHBcAg expression group and nHBcAg expression group as well as that between cHBcAg expression group and c-nHBcAg expression group. However there was no significant difference between nHBcAg expression group and c-nHBcAg expression group (p<0.001, Table 5).

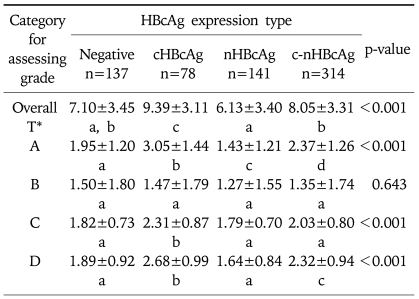

2) The grade of necroinflammatory activity according to the intracellular expression of HBcAg

The mean overall grade of necroinflammatory activity was 9.39±3.11 in cHBcAg expression group, 6.13±3.40 in nHBcAg expression group, 8.05±3.31 in c-nHBcAg expression group and 7.10±3.45 in HBcAg negative group (p<0.001, Table 6). There was a statistical significance in the difference between cHBcAg expression group, nHBcAg expression group and c-nHBcAg expression group and that between HBcAg negative and nHBcAg expression group. However, there were no significant differences between HBcAg negative and c-nHBcAg expression group and between HBcAg negative group and cHBcAg expression group (Table 6).

Table 6.

Average Necroinflammatory Grade according to Intrahepatic HBcAg Expression

Statistical significances were tested by one-way ANOVA., Values are Mean±SD.

A, periportal or periseptal interface hepatitis (piecemeal necrosis); B, confluent necrosis; C, focal (spotty) lytic necrosis, apoptosis, and focal inflammation; D, portal inflammation.

*The same letters indicate insignificant difference between the groups based on Tukey's multiple comparison test.

In each category, in cases of periportal or periseptal interface hepatitis, the mean grade of hepatic tissue was 3.05±1.44 in cHBcAg expression group, 1.43±1.21 in nHBcAg expression group, 2.37±1.26 in c-nHBcAg expression group and 1.95±1.20 in HBcAg negative group with significant differences between all groups (p<0.001, Table 6). The mean grade of confluent necrosis was 1.47±1.79 in cHBcAg expression group, 1.27±1.55 in nHBcAg expression group, 1.35±1.74 in c-nHBcAg expression group and 1.50±1.80 in HBcAg negative group. There was no statistical significance in differences between all groups (p=0.643, Table 6). The mean grades of focal (spotty) lytic necrosis, apoptosis and focal inflammation were 2.31±0.87 in cHBcAg expression group, 1.79±0.70 in nHBcAg expression group, 2.03±0.80 in c-nHBcAg expression group and 1.82±0.73 in HBcAg negative group (p<0.001, Table 6). There were significant differences between cHBcAg expression group and the other groups. Differences between the other groups had no statistical significance. The mean grade of portal inflammation was 2.68±0.99 in cHBcAg expression group, 1.64±0.84 in nHBcAg expression group, 2.32±0.94 in c-nHBcAg expression group and 1.89±0.92 in HBcAg negative group with a statistical significance in differences between groups except that between nHBcAg expression group and HBcAg negative group (p<0.001, Table 6).

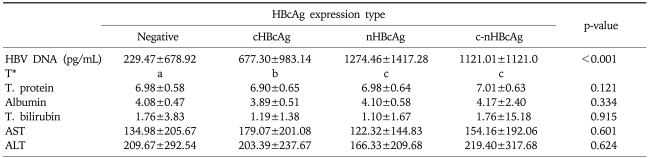

3. The correlation between laboratory findings and intracellular expression of HBcAg

Mean values of HBV DNA quantification were 677.30±983.14 (pg/mL) in cHBcAg expression group, 1274.46±1417.28 in nHBcAg expression group, 1121.01±1121.0 in n-cHBcAg expression group and 229.47±678.92 in HBcAg negative group. This showed that mean value of HBV DNA quantification was the highest in the nHBcAg expression group, which was followed by c-nHBcAg expression group, cHBcAg expression group and HBcAg negative group in the corresponding order. There was no significant difference between nHBcAg expression group and c-nHBcAg expression group. The differences between other groups reached a statistical significance (p<0.001, Table 7). Mean values of laboratory measurements, including serum AST and ALT, total bilirubin, total protein and albumin, showed no significant inter-group differences (p>0.05, Table 7).

Table 7.

Other Laboratory-Test Data according to Intrahepatic HBcAg Expression

Statistical significances were tested by one-way ANOVA., Values are Mean±SD.

HBV DNA, hepatitis B virus DNA; T. protein, total protein; T. bilirubin, total bilirubin; AST, aspartate aminotrasferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

*The same letters indicate non-significant difference between the groups based on Tukey's multiple comparison test.

The difference in the positive rate for HBeAg depending on the intracellular distribution of HBcAg was also assessed. Of the total 670 patients, 651 with available HBeAg data were included in this analysis. The positive rate for HBeAg was 74.7% (59 cases) in cHBcAg expression group, 90.6% (116 cases) in nHBcAg expression group, 90.3% (279 cases) in the c-nHBcAg group and 55.6% (75 cases) in the HBcAg negative group. This showed that the positive rate for HBeAg was the highest in nHBcAg expression group, which was followed by c-nHBcAg exspression group, cHBcAg expression group and HBcAg negative group, respectively (p<0.001, Table 8).

Table 8.

HBeAg Expression according to Intrahepatic HBcAg Expression

Statistical significances were tested by Chi-square test., Values are numbers of patients.

DISCUSSION

In 1976, Ray et al.16 reported that the intracellular distribution of HBsAg was concerned with the clinical stage. These authors also noted that the severity of inflammation and the histological activity were both higher in cases where HBsAg was distributed on the plasma membrane. Thereafter, it has been reported that HBsAg was distributed along the plasma membrane of hepatocytes in areas where piecemeal necrosis is observed on histopathologic analysis. This suggested that the distribution of HBsAg on the plasma membrane was closely related to the histological activity of hepatitis. Chu et al.7 reported that the distribution of HBsAg on the plasma membrane was also associated with the degree of viral proliferation. Recently in Korea, however, it has been reported that there was no significant difference in the histological activity depending on the site of HBsAg expression.13,14 This suggested that there was an inconsistence between the Korean and Western studies.

In this study, we compared both of the histological activity of hepatitis and the degree of viral replication according to intracellular expression of HBsAg and HBcAg in 670 patients who were diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B in a single institution. There was no correlation between the intracellular expression of HBsAg and the histological activity of hepatitis. This is inconsistent with the report that the histological activity was higher in mHBsAg expression. Presumably, this might not be associated with the stage of viral replication, although HBsAg is a major antigen for humoral immunity of hepatitis B, not that for cell-mediated immunity.

It has been reported that HBcAg was stronger by 100 times than HBsAg in provoking the immune responses of B cell or T cell.17 There are no controversies on the association between the intracellular expression of HBcAg and the histological activity of hepatitis. It is known that the histological activity and the severity of inflammation are both higher in cases of cHBcAg expression than those of nHBcAg expression.3,10,11,14 In association with the intracellular HBcAg expression and the viral proliferation, several study pointed out that the intranuclear distribution of HBcAg was associated with a higher concentration of HBV DNA.7,10,12 In addition, the degree of the expression of HBcAg within the nucleus was positively correlated with the concentration of HBV DNA.11

In this study, histological activity and viral replication was evaluated in the same population. The histological activity was higher in cHBcAg expression than those in nHBcAg expression. This is consistent with previous reports that have been reported.3,10,11,14,16 The HBV DNA level and seropositivity of HBeAg were lower in cHBcAg than in nHBcAg. This indicates that the degree of viral replication is low, which is contradictory to the previous reports that HBcAg is not concerned with the degree of viral replication.18 In summary, both the histological activity of hepatitis and the degree of viral replication have close relationships with the intracellular expression of HBcAg.

We compared between cHBcAg expression, nHBcAg expression and c-nHBcAg expression. Although there was no statistically significant difference between nHBcAg group and n-cHBcAg group, the histological activity of hepatitis in c-nHBcAg expression was lower than in cHBcAg expression and higher than in nHBcAg expression. Besides, the degree of viral replication in c-nHBcAg expression was higher than in cHBcAg expression and lower than in nHBcAg expression. Besides, the histological activity and the degree of viral replication in c-nHBcAg expression were median values compared to cHBcAg expression and nHBcAg expression. Presumably, these results might be associated with the phase of viral replication. In the immune tolerance phase, during which the significant injury of hepatocytes is absent, the proliferation of virus mainly occurs. In this phase, HBcAg is mainly distributed within the nucleus. Thereafter, as the immune removal phase is progressed, hepatocytes are destroyed and the liver is histologically damaged. In the mean time, the differentiation and proliferation of liver cells become active, during which the degree of viral replication is decreased and HBcAg which is mainly present within the nucleus is shifted to the cytoplasmic space.19 The histological activity and the degree of viral replication in c-nHBcAg expression were a median value compared to cHBcAg expression and nHBcAg expression. Presumably, it can be contemplated the that cases of c-nHBcAg expression were in the status of progressing from the immune tolerance phase to immune clearance phase. To date, many studies have comparatively examined between cHBcAg expression and nHBcAg expression. However, few studies have included c-nHBcAg expression. Cho et al.14 individually analyzed c-nHBcAg expression, but they could not elucidate the statistically significant results due to the small number of patients. Accordingly, the results of this study is of great significance since it analyzed 670 cases based on the past 10-year clinical data.

In general, during the natural course of hepatitis, the serum levels of hepatic enzymes are mostly normal during the immune tolerance phase. In this study, however, mean values of serum level of AST and ALT in the nHBcAg expression, assumed to be related to the immune tolerance phase, were 122.32 and 166.33 IU/L, respectively. These values were lower than those in the cHBcAg expression, but were 3- to 4-fold higher compared to the normal value. In addition, in the nHBcAg expression, 25 (17%) of 140 cases had a normal value of hepatic enzymes. In the cHBcAg-positive group, this value was 10% (8/78) (data not shown). In other words, not all the cases of the nHBcAg expression underwent immune tolerance phase. Presumably, this might be because our study was conducted in hospitalization patients. Most of the patients who were hospitalized for liver biopsy presented with a high level of hepatic enzymes at the time of admission. It is highly probable that patients underwent the progression of immune tolerance phase into immune removal phase or they developed aggravated course of hepatitis after the time was elapsed following the progression into the immune removal phase. We could not estimate the exact duration of active hepatitis, and did not clarify the correlations. In this study, however, the nHBcAg expression corresponded to the former and the cHBcAg expression to the later.

In liver biopsy, the histologic grade and stage that represent the severity including the inflammation or necrosis of hepatic tissue were first quantified when Knodell used the histologic activity index (HAI) in 1985.20 Thereafter, it has been widely used. It has been underscored the inflammation and piecemeal necrosis of hepatic portal vein as well as the inflammation of hepatic lobules which are important indicators associated with poor prognosis.21,22 Since then, Ishak et al. reported about the modified HAI in 1995.15 This has been used until now. In the modified HAI, the inflammation of hepatic lobules as well as piecemeal necrosis (A) and portal inflammation (D) were divided into confluent necrosis (B), focal (spotty) lytic necrosis, apoptosis and focal inflammation (C). Then, regarding each category ranging from 1 to 4 or 6, each score was added and then assigned with the histological grade. Thus, it was possible to make an accurate, detailed grading system which was associated with a prognosis.23 In our study, in order to evaluate the relationship between the intracellular expression of HBcAg and the histopathologic findings, the modified HAI and staging system were used. The overall mean values of histological grade showed that cHBcAg was higher than nHBcAg. In each category, however, the different results were shown (Table 4). Piecemeal necrosis and portal inflammation showed the same results as the overall grade. Of the categories representing the inflammation of hepatic lobules, focal necrosis also showed the same findings as the overall grade. However confluent necrosis showed no difference depending on the distribution of HBcAg. Kim et al.3 compared the CD4+ T cell (Helper T cell)/CD8+ T cell (Suppressor or cytotoxic T cell) ratio between the portal vein and the hepatic lobules. Based on the findings that the CD4+ / CD8+ T cell ratio was higher in the portal vein, these authors maintained that the inflammations of portal vein and hepatic lobules arose from the different pathophysiology. To put this in another way, the inflammation of hepatic lobules arose from the destruction of HBV-infected hepatocytes mainly via cytotoxic T cell, when that of portal tract was due to autoimmune disease. To date, however, no studies have individually compared the intracellular site of HBcAg, the degree of hepatic lobule inflammation and that of portal vein. In our study, the degree of the inflammations of hepatic portal vein and peri-portal area was associated with the intracellular expression of HBcAg. Among inflammation of hepatic lobules, confluence necrosis in particular, was not a related factor. However, nothing is known about the exact mechanism by which the inflammations of hepatic lobules and portal vein occur. Further studies are warranted to examine the correlation between the degree of hepatic lobule inflammation and the degree of viral replication.

The limitations of the current study is a lack of randomization of patient enrollment due to the retrospective chart analysis. Furthermore, since the degree of intracellular expression of HBcAg could not be quantified, it was difficult to elucidate the correlations between the degree of HBcAg expression, histopathological findings and the degree of viral replication. Now that this study was conducted in a sufficient size of patient population, its results would be of great clinical significance. It also has a significance in that it individually compared between cHBcAg expression, nHBcAg expression and c-nHBcAg expression. It drew a significant correlation between the pattern of HBcAg expression and the degree of viral replication. Furthermore, in regard to the histologic activity, using the modified grade, the differences in the degree of inflammations of hepatic lobules as well as the portal tract and the peri-portal area were individually compared. Thus, it was confirmed that the site of HBcAg expression was concerned with the degree of inflammations of the portal tract and the peri-portal area. However, in the inflammation of hepatic lobules, the confluence necrosis was not associated with HBcAg expression.

In conclusion, in patients with chronic hepatitis B, the intracellular expression of HBsAg was not associated with the histological activity. In addition, the histological activity was higher and the degree of viral replication was lower in cHBcAg expression than those in nHBcAg expression. The portal vein and the peri-portal inflammation varied depending on the intracellular distribution of HBcAg. However, with regard to inflammation of hepatic lobules, confluence necrosis was not associated with the intracellular distribution of HBcAg. Based on the above results, it can be inferred that HBcAg is an important immunological marker for human hepatitis B. The expression of HBcAg is differently observed during the transformation of immune tolerance phase into that of immune removal. In addition, our results indicate that the portal vein and the inflammations of peri-portal area and hepatic lobules arise from the different pathophysiology.

References

- 1.Hsu HC, Su IJ, Lai MY, et al. Biologic and prognostic significance of hepatocyte hepatitis B core antigen expression in the natural course of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 1987;5:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim BS, Jeong JW, Park DH, Choi SW, Kang HJ, Jeong WS. The relationship of HBV DNA-Polymerase activity & HBeAg in various liver diseases. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1988;20:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim KH, Kim HJ, Chon CY, Kang JK, Choi HJ. Analysis of nuclear HBeAg, serum HBeAg/anti-HBe status and liver histology in HBsAg positive chronic. Korean J Intern Med. 1985;28:761–769. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song IS, Kim CY, Lee HS, Choi SW, Seo JS. Relationship between serum HBV DNA level and HBeAg / anti - HBe. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1989;21:876–881. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu CM, Yeh CT, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. Subcellular localization of hepatitis B core antigen in relation to hepatocyte regeneration in chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1926–1932. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90760-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadziyannis SJ, Lieberman HM, Karvountzis GG, Shafritz DA. Analysis of liver disease, nuclear HBcAg, viral replication, and hepatitis B virus DNA in liver and serum of HBeAg Vs. anti-HBe positive carriers of hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1983;3:656–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu CM, Liaw YF. Intrahepatic distribution of hepatitis B surface and core antigens in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: hepatocyte with cytoplasmic/membranous hepatitis B core antigen as a possible target for immune hepatocytolysis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:220–225. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90863-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu CM, Liaw YF. Membrane staining for hepatitis B surface antigen on hepatocytes: a sensitive and specific marker of active viral replication in hepatitis B. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:470–473. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.5.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray MB, Desmet VJ, Fevery J, De Groote J, Bradburne AF, Desmyter J. Distribution patterns of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the liver of hepatitis patients. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29:94–100. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serinoz E, Varli M, Erden E, et al. Nuclear localization of hepatitis B core antigen and its relations to liver injury, hepatocyte proliferation, and viral load. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:269–272. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim TH, Cho EY, Oh HJ, et al. The degrees of hepatocyte cytoplasmic expression of hepatitis B core antigen correlate with histologic activity of liver disease in the young patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:279–283. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burrell CJ, Gowans EJ, Rowland R, Hall P, Jilbert AR, Marmion BP. Correlation between liver histology and markers of hepatitis B virus replication in infected patients: a study by in situ hybridization. Hepatology. 1984;4:20–24. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeen YM, Park CI. The expression rate and pattern of HBcAg and HBsAg in the hepatocytes according to the histologic activity of cirrhosis. Korean J Pathol. 1995;29:669–677. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho KB, Sohn JH, Park KS, et al. The correlation between the histologic activity and fibrosis and the distribution of intrahepatic HBsAg and HBcAg in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Korean J Hepatol. 2001;7:401–412. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray MB, Desmet VJ, Fevery J, De Groote J, Bradburne AF, Desmyter J. Distribution patterns of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the liver of hepatitis patients. J Clin Pathol. 1976;29:94–100. doi: 10.1136/jcp.29.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee YS. Mechanims of immune responses and liver cell injury in response to hepatitis B virus infection. Korean J Hepatol. 1997;3:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn HJ, Kim KH, Park YN, Kim HG, Park CI. Expression pattern of hepatitis B viral core antigen (HBcAg) and surface antigen (HBsAg) in liver of the inactive HBsAg carriers. Korean J Pathol. 1990;24:120–127. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han JY, Jung WH, Chon CY, Park CI. The tissue expression of HBsAg and HBcAg in hepatocellular carcinoma and peritumoral liver. Korean J Pathol. 1993;27:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431–435. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Popper H. Changing concepts of the evolution of chronic hepatitis and the role of piecemeal necrosis. Hepatology. 1983;3:758–762. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung WK, Han JY. Pattern of histologic progression from acute and chronic hepatitis B to cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 1996;2:134–144. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakaji M, Hayashi Y, Ninomiya T, et al. Histological grading and staging in chronic hepatitis: its practical correlation. Pathol Int. 2002;52:683–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]