Abstract

Background/Aims

Gastric cancer is the leading malignancy in Korea and early detection through the health screening seems to be important. The aims of this study were to investigate the features of gastric neoplasms detected during screening, and to figure out the risk factors of these lesions.

Methods

From October 2003 to September 2005, subjects who visited Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center for health check-up were included in the study. The program included a questionnaire and tests including anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody, esophagogastroduodenoscopy or double contrast upper gastrointestinal study. To figure out the risk factors, an age and gender-matched, four-fold sized control group was selected from the subjects.

Results

Of 25, 432 subjects, 122 cases of gastric neoplasms were detected including 61 adenocarcinoma (45 early gastric cancers), 53 adenoma, 7 mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and one metastatic cancer. There was no significant statistical difference in basal characteristics of the subjects between gastric adenocarcinoma and adenoma. When comparing with the control group those without gastric neoplasms, smoking history, family history of stomach cancer, and H. pylori seropositivity were found to be significant risk factors for gastric neoplasms. Metabolic syndrome was more prevalent in adenoma than in the control (p<0.05).

Conclusions

The health screening may be beneficial in early detection of gastric cancer. In addition, metabolic syndrome might be related with gastric adenoma.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Screening, Stomach, Adenoma, Risk factor, Helicobacter pylori

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the second most frequent cancer worldwide,1 and Korea has been reported to be the most prevalent country together with Japan.2 Considering gastric cancer as a major disease for the improvement of health, a national wide screening system for gastric cancer is performed in Korea since 1980 included in a central cancer registry project. Of various malignant tumors, gastric cancer occurs most frequently and causes a large proportion of medical expense along with its high mortality. According to the 2002 report of the Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR), the age-standardized rate was 69.6 in 100,000 male and 26.8 in female.3 Recently, its mortality rate has been reported to be second highest next to lung cancer.4 Thus, gastric cancer, in regard to the incidence and mortality, causes biggest part of the annual cost for cancer therapy,5 and it is an important disease in terms of economic expenses. Therefore, studies focusing on the prediction of risk factors, early detection, and screening tests are required.

There is a worldwide decreasing trend for gastric cancer incidence,6-8 and it has been reported that the changes of diet and the improvement in living standard might be related rather than aggressive prophylactic policies.9-11 Besides, the most important factor determining the prognosis of gastric cancer is the stage of the tumor at the time of detection. In early gastric cancers (EGC), 5-year survival rate has been reported to be higher than 90%,12,13 with a large proportion of disease being detected in asymptomatic adults.14,15 Therefore, it can be speculated that more active gastric cancer screening is associated with the increase in survival rate in regions with a high incidence of gastric cancer.16-19

Considering the importance of tumor stage and the impact of screening test in Korea, gastric cancer screening program should be performed systemically and continuously. A nation-wide gastric cancer screening program was launched from the year 2000 by the National Health Insurance Cooperation (NHIC). However, it still has numerous limitations as a whole. As the demand for gastric cancer screening test is increasing in Koreans, some may seek screening program on their own expenses.20

To evaluate the status and risk factors, we examined the incidence of gastric cancer in adults undergoing the screening test voluntarily in a health care center as well as the risk factors pertinent to gastric neoplasm. In addition, the incidence of precancerous lesion without malignant transformation and their risk factors were analyzed for future cohort observation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

The study subjects are those who underwent esophagogastroduodenography (EGD) or upper gastrointestinal study (UGIS) as a screening test between October 2003 to September 2005 at Seoul National University Hospital, Healthcare System Gangnam Center (Gangnam center). A case-control analysis was performed. The categories of the screening test performed at the Gangnam center consisted of; (i) a questionnaire for the analysis of factors pertinent to health and life style, (ii) physical measurement and screening tests for various disease, and (iii) screening tests for upper gastrointestinal tract diseases.

2. A questionnaire for the analysis of factors pertinent to health and life style

The questionnaire consisted of demographic information, past medical history, life style, socioeconomic status, family history, symptoms, and questions on diet, and the questionnaire was filled out voluntarily and then converted to computer data by an automatic computer input system. Smoking history, drinking history, family history of gastric cancer, follow-up interval for upper gastrointestinal examination, and socioeconomic status were selected as variables associated with the development of gastric cancer as well as precancerous lesions.

Smoking history was classified as; (i) non-smoker when the subject never smoked or quitted smoking for longer than 5 years, (ii) ex-smoker when the subject quitted smoking within past 5 years, (iii) current smoker when the subject currently smoked regardless of the amount of smoking. Drinking was classified as; (i) non-drinker when the subject never consumed or drank less than once a month, (ii) social drinker when the subject drank 1-2 times per week, (iii) heavy drinker when the subject drank more than 3 times per week regardless of the amount of drinking. Family history of gastric cancer was considered to be present when there was a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. Health management behaviors were considered to be preferable when upper gastrointestinal screening test were done within 3 years. Socioeconomic status was classified as; (i) low level if monthly total income was less than 3,000,000 Won, (ii) mid-low level when monthly total income was between 3,000,000 Won and 5,000,000 Won, (iii) mid-high level when monthly total income was between 5,000,000 Won and 10,000,000 Won, and (iv) high when monthly total income was more than 10,000,000 Won.

3. Physical measurement, screening tests for various diseases, and examination of risk factors

Height, weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure were measured and screening tests for various diseases and serological test for risk factors of disease development were done. In addition, body mass indices, abdominal obesity, blood pressure, serum lipid profile, and fasting blood sugar test were selected. As a risk factor of stomach disease, anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) antibody IgG tests (H. pylori serum antibody test) were performed.

Body Mass Index was presented as height (kg)/weight (m2). The waist circumference was measured in standing posture and defined as the circumference around the umbilicus measured vertical to the earth. Waist circumference greater than 90 cm in male and greater than 80 cm in female were classified as subjects with abdominal obesity.22 In regard to blood pressure, systolic blood pressure higher than 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure higher than 85 mmHg, or subjects on antihypertensive medications were classified as high blood pressure group. In categories of serum lipid test, blood triglyceride level higher than 150 mg/dL or subjects on treatment for hypertriglycemia were classified as hypertriglydceridemia group. Regarding high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol), HDL-cholesterol less than 40 mg/dL in male and less than 50 mg/dL in the female, or subjects under medication for hyperlipidemia were classified as hyperlipidemia group. Fasting blood glucose level higher than 100 mg/dL or subjects under the treatment for diabetes were considered as diabetics. In summary, subjects with more than three of above categories including abdominal obesity were considered to have metabolic syndrome positive.21

Presence of past history for the treatment for H. pylori was included in the questionnaire. However, seropositivity was the only way to assess for the presence of H. pylori since histological test and urea breath test were not performed.

4. Screening tests for upper gastrointestinal tract diseases

Either EGD or UGIS was performed. For the cases that revealed abnormalities in UGIS, EGD was subsequently performed to confirm the abnormalities.

5. The data warehouse of the Gangnam center HEALTHWATCH® ver 1.0

Of the computerized medical records, all computerized record and test data were retrieved, combined and managed by the HEALTHWATCH® ver 1.0. The data accumulated consistently could be retrieved anytime according to the desired query and condition, which is uploaded in a daily unit. The data of this study could be also obtained by the use of the HEALTHWATCH® ver 1.0.

6. Selection of the control group for the analysis of risk factors and statistical analysis

Associated risk factors were assessed in the subjects with gastric neoplasm. To analyze the risk factors for the disease development, a four-fold sized age and gender-matched subjects were retrieved as a control group. For statistical analysis, the SPSS 12.0 program was used, and p-value<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Feature of stomach neoplasm detected by screening tests and the demographic data of the subjects

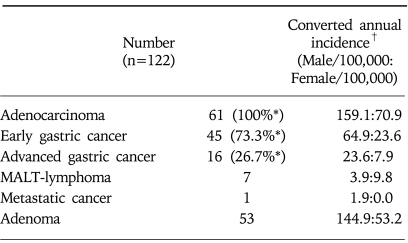

A total of 25,432 subjects underwent screening tests for the upper gastrointestinal diseases either by EGD or UGIS at Gangnam center from October 2003 to September 2005. Of these cases, male was 14,144 and female was 11,288 cases with a mean age of 49.9 year-old. Gastric neoplasms were detected in 122 patients consisted of 53 adenoma, 45 EGC, 16 advanced gastric cancer (AGC), 7 mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, and one metastatic gastric cancer. The incidence of gastric neoplasms detected by the screening test was 0.48%. When adjusted by the observational period, the crude annual incidence in 100,000 individuals was 159.1 cases in male and 70.9 cases in female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Gastric Neoplasm Detected during the Health Screening Examination

MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

*Percent of adenocarcinoma.

†Simply calculated from the incidences of this population (25,432 subjects) and adjusted by period (2 years).

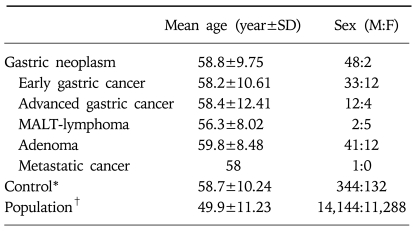

In the demographic characteristics of the disease group and the screened population, mean age of the disease group was higher than that of the population group, and male showed more prevalence than female. Age and gender-matched four-fold sized control group were selected for case-control study to analyze the risk factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic Data of Patients with Gastric Neoplasms

SD, standard deviation; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

*Age and gender-matched, four-fold sized control group was randomly selected from the population.

†25,432 subjects.

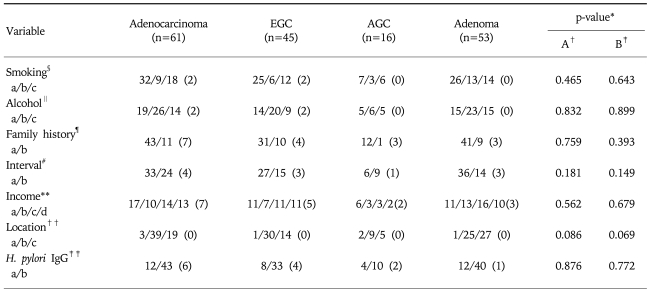

2. The analysis of clinical characteristics of the patients with gastric neoplasms

Among gastric neoplasms detected by the screening, gastric adenocarcinoma was the most common malignant tumor and gastric adenoma was the most common benign tumor, retrospectively. Among gastric adenocarcinoma, the proportion of EGC was 73.8% being the main malignancy detected by the screening. The detection rate of gastric adenoma was comparable to that of the gastric adenocarcinoma. As factors pertinent to gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric adenoma, smoking history, drinking history, family history, health management behavior on receiving regular screening tests, socioeconomic status, location of lesion, H. pylori seropositivity were examined. However, all factors revealed no statistical significance between two groups. In similar, there was no significant difference between EGC and AGC (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of Demo-clinical Factors between Gastric Adenoma and Adenocarcinoma

Missing datas are written as numbers in parenthesis. EGC, early gastric cancer; AGC, advanced gastric cancer.

*Pearson-Chi square test.

†A: Adenocarcinoma vs. adenoma.

‡B: EGC vs. AGC vs. adenoma.

§Smoking, a: non- or ex-smoker more than 5 years, b: ex-smoker less than 5 years, c: current smoker.

∥Alcohol, a: non-drinkers, b: social drinkers, c: heavy drinkers who drink more than 3 times a week.

¶Family history, a: answered, none of stomach cancer, b: stomach cancer, in first-degree relative (siblings, parents or grandparents).

#Interval, a: health check-up within 3 years including upper GI screening, b: no health check-up within 3 years.

**Income (won/month), a: low <3,000,000 b: mid-low 3,000,000-5,000,000, c: mid-high, 5,000,000-10,000,000, d: high >10,000,000.

††Location, a: cardia, b: non-cardia, non-antrum, or unspecified, c: antrum.

‡‡H. pylori IgG, a: negative, b: positive.

Regarding the location of lesions, gastric adenoma was most frequently detected on the antrum, especially when adenocarcinoma was classified into EGC and AGC, (Table 3).

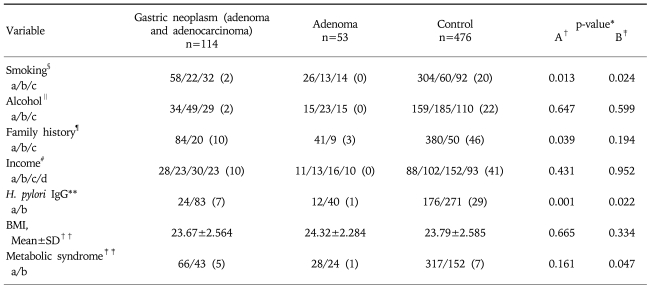

3. Analysis of risk factors pertinent to the development of gastric adenoma and adenocarcinoma

When analyzing the associated risk factors with gastric adenoma and adenocarcinoma, smoking history, family history of gastric cancer in first-degree relatives, H. pylori seropositivity were found to be statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Demo-clinical Characteristics between Gastric Neoplasm and Control

Missing datas are written as numbers in parenthesis. SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index.

*Pearson-Chi square test except BMI

†A: Gastric neoplasm vs. control.

‡B: Adenoma vs. control.

§Smoking, a: non- or ex-smoker more than 5 years, b: ex-smoker less than 5 years, c: current smoker.

∥Alcohol, a: non-drinkers, b: social drinkers, c: heavy drinkers who drink more than 3 times a week.

¶Family history, a: answered, none of stomach cancer, b: stomach cancer, in first-degree relatives (siblings, parents or grandparents).

#Income (Won/month), a: low <3,000,000, b: mid-low 3,000,000-5,000,000, c: mid-high, 5,000,000-10,000,000, d: high >10,000,000.

**H. pylori IgG, a: negative, b: positive.

††BMI, weight (kg)/height (m2), by Levene's test.

‡‡Metabolic syndrome, a: absence, b: presence defined when any three of following five traits, abdominal obesity (Asian criteria), serum trigylceride, serum HDL-cholesterol, blood pressure and fasting plasma glucose according to 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program [Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III updated in 2005].

In gastric adenoma, smoking history and H. pylori seropositivity were significant risk factors although the family history of gastric cancer did not show any statistical significance. The incidence of metabolic syndrome was significantly higher in gastric adenoma patients (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Most of the gastric cancer detected by screening tests was EGC rather than AGC, which reveals different patterns from those of the patients who visited hospitals and private clinics for its treatments.22 In addition, it showed a noticeably higher incidence than the KCCR result, and the onset age was somewhat lower,3 which suggested that aggressive screening tests may be beneficial in early detection of gastric cancer. When analyzing the risk factors of EGC and AGC, variables showing a statistical significance could not be detected, thus making it difficult to predict which subjects are more prone to AGC and for which subjects to apply differential screening plans. In the disease group with gastric neoplasm, smoking history, family history, status of H. pylori infection were shown to be risk factors in comparison with the control group in accordance with previous studies.23-26 Prospective studies are now undergoing in order to evaluate the effect on management of these risk factors. However, result of our study could suggest that aggressive screening tests may be recommended in subjects with the above risk factors.

It is interesting that gastric adenoma is as commonly detected as gastric cancer in the screening examinations. As the precursor lesion of gastric cancer, chronic atrophic gastritis has been accepted most widely,27,28 nevertheless, the association of the neoplasm of gastric epithelial cells, gastric adenoma, has been mentioned cautiously despite its rarity.29 Several significances of gastric adenoma could be summarized through our results.

First, as a screening method for the stomach, either EGD or UGIS could be selected. In our center, more than 90% of the subjects selected EGD as the initial screening test (data now shown) rather than UGIS which resulted in the better detection rate for more fine lesions.30 In other words, it reflects that as a suitable screening method to detect early precursor lesion for gastric cancer, EGD is appropriate to be used as a screening test.

The second important point is about the risk factors associated gastric adenoma. As for risk factors, chronic atrophic gastritis, H. pylori infection, and several others have been described previously.30-32 In our study, smoking history and H. pylori seropositivity were shown to be the risk factors associated with gastric cancer in substantial parts. However, different from gastric adenocarcinoma, the incidence of metabolic syndrome was found to be significantly high in gastric adenoma. Studies describing the association of gastric adenoma and metabolic syndrome have not been reported yet. Based on the results of our study, gastric adenoma was not associated with the family history of gastric cancer but associated with metabolic syndrome. In addition, the mean age of gastric adenoma did not show a significant difference from that of EGC. This discrepancy may suggest that gastric adenoma may have some risk factors environmentally controlled such as smoking history, H. pylori infection and metabolic syndrome. The detection time of gastric adenoma is similar to that of the gastric adenocarcinoma, and thus it may reflect, a different pattern of gastric neoplasms developing at a similar period rather than undergoing the adenoma-carcinoma sequence.

The third point is the fact that with the aid of computerization of medical records and the availability of an adequate data warehouse, statistical attempts on unexpected risk factors could be made successfully. Based on the data retrieved by the HEALTHWATCH®, the association of gastric adenoma and metabolic syndrome could be inferred, and the data stored constantly could detect cohort effects even if it were not a prospective study. Therefore, when performing screening tests, the combining and retrieval of scattered individual data would be an important issue.

In conclusion, gastric cancer detected in our study was EGC in most cases, and thus the improvement of the survival rate of gastric cancer through screening tests could be anticipated. Regarding risk factors associated with gastric neoplasm, smoking, the family history of gastric cancer, H. pylori infection were shown to be significant similarly to previous studies. Gastric adenoma, which was frequently detected during the screening test had similar risk factors with gastric adenocarcinoma. However, metabolic syndrome appears to play a certain role for the development of gastric adenoma unlike gastric adenocarcinoma. Further data needs to be gathered and analyzed in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank MRCC (medical research collaborating center) of Seoul National University Hospital for their assistance in statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Cancer surveillance database. World Health Organization. Available at: www.dep-iarc.fr.

- 2.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB. Cancer incidence in five continents. volume VIII. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2003. IARC Scientific Publication No. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 3.2002 Annual report of Korea Central Cancer Registry. Korea Central Cancer Registry Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea. Available at: www.ncc.re.kr.

- 4.Korean statistical information system. Korea National Statistical Office, Republic of Korea. Available at: www.kosis.nso.go.kr.

- 5.Annual report of national health insurance. National Health Insurance Corporation, Republic of Korea. Available at: www.nhic.or.kr.

- 6.Aoki K, Kurihara M, Hayakawa N, et al. Death rates for malignant neoplasms for selected sites by sex and 5-year age group in 33 countries 1953-57 to 1983-87. Nagoya, Japan: University of Nagoya Coop Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ries LAG, Melbert D, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2004. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. Available at: www.seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roder DM. The epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5(suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-002-0203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs CS, Mayer RJ. Gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:32–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terry P, Nyren O, Yuen J. Protective effect of fruits and vegetables on stomach cancer in a cohort of Swedish twins. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:35–37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980330)76:1<35::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue M, Tsugane S. Epidemiology of gastric cancer in Japan. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:419–424. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.029330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoh H, Oohata Y, Nakamura K, Nagata T, Mibu R, Nakayama F. Complete ten-year postgastrectomy follow-up of early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 1989;158:14–16. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kikuchi S, Katada N, Sakuramoto S, et al. Survival after surgical treatment of early gastric cancer: surgical techniques and long-term survival. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s00423-004-0462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kong SH, Park DJ, Lee HJ, et al. Clinicopathologic features of asymptomatic gastric adenocarcinoma patients in Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:1–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota H, Kotoh T, Masunaga R, et al. Impact of screening survey of gastric cancer on clinicopathological features and survival: retrospective study at a single institution. Surgery. 2000;128:41–47. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.106812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert R, Guilloux A, Oshima A, et al. Incidence and mortality from stomach cancer in Japan, Slovenia, and the USA. Int J Cancer. 2002;97:811–818. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dan YY, So JB, Yeoh KG. Endoscopic screening for gastric cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:709–716. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan YK, Fielding JW. Early diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:821–829. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida S, Saito D. Gastric premalignancy and cancer screening in high-risk patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:839–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibbard JH, Peters E. Supporting informed consumer health care decisions: data presentation approaches that facilitate the use of information in choice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2003;24:413–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.141005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meigs JB. The metabolic syndrome (Insulin resistance syndrome or syndrome X) 2007. [UpToDate connected on 20th Apr]. Available at: www.uptodateonline.com.

- 22.Korea Gastric Cancer Association. Nation-wide gastric cancer report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2002;2:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brenner H, Arndt V, Bode G, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Stumer T. Risk of gastric cancer among smokers infected with Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:446–449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niv Y. Family history of gastric cancer: should we test and treat for Helicobacter pylori? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:204–208. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toyoshima H, Hayashi S, Hashimoto S, et al. Familial aggregation and covariation of disease in a Japanese rural community: comparison of stomach cancer with other diseases. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:446–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process-First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whiting JL, Sigurdsson A, Rowlands DC, Hallissey MT, Fielding JW. The long term results of endoscopic surveillance of premalignant gastric lesions. Gut. 2002;50:378–381. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Gastric adenoma: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276–1285. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Haruma K, et al. Correlation of ratio of serum pepsinogen I and II with prevalence of gastric cancer and adenoma in Japanese subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1090–1096. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rocco A, Caruso R, Toracchio S, et al. Gastric adenomas: Relationship between clinicopathological findings, Helicobacter pylori infection, APC mutations and COX-2 expression. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(suppl 7):vii103–vii108. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotoda T, Saito D, Kondo H, et al. Endoscopic and histological reversibility of gastric adenoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34(suppl 11):91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]