Abstract

Inflammation is implicated in the progressive nature of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, but the mechanisms are poorly understood. A single systemic lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 5 mg/kg, i.p.) or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα, 0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) injection was administered in adult wild-type mice and in mice lacking TNFα receptors (TNF R1/R2−/−) to discern the mechanisms of inflammation transfer from the periphery to the brain and the neurodegenerative consequences. Systemic LPS administration resulted in rapid brain TNFα increase that remained elevated for 10 months, while peripheral TNFα (serum and liver) had subsided by 9 h (serum) and 1 week (liver). Systemic TNFα and LPS administration activated microglia and increased expression of brain pro-inflammatory factors (i.e., TNFα, MCP-1, IL-1β, and NF-κB p65) in wild-type mice, but not in TNF R1/R2−/− mice. Further, LPS reduced the number of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) by 23% at 7-months post-treatment, which progressed to 47% at 10 months. Together, these data demonstrate that through TNFα, peripheral inflammation in adult animals can: (1) activate brain microglia to produce chronically elevated pro-inflammatory factors; (2) induce delayed and progressive loss of DA neurons in the SN. These findings provide valuable insight into the potential pathogenesis and self-propelling nature of Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: TNFα, LPS, substantia nigra, microglia, neurodegeneration, neuroinflammation

Introduction

Inflammation and microglial activation is a common component of the pathogenesis for multiple neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease (PD), Huntington's disease, Multiple sclerosis, and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Nguyen et al., 2002). Microglia, the resident innate immune cells in the brain, actively monitor their environment and can become over-activated in response to diverse cues to produce cytotoxic factors, such as superoxide (Colton and Gilbert, 1987), nitric oxide (Liu et al., 2002; Moss and Bates, 2001), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (Lee et al., 1993; Sawada et al., 1989). While microglial activation is necessary and critical for host defense, over-activation of microglia is neurotoxic (McGeer et al., 2005; Polazzi and Contestabile, 2002). At this time, the mechanisms initiating deleterious neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disease are poorly understood.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), endotoxin from gram-negative bacteria, damages DA neurons only in the presence of microglia (Gao et al., 2002; Gibbons and Dragunow, 2006). Further, LPS activation of microglia both in vivo and in vitro causes the progressive and cumulative loss of DA neurons over time (Gao et al., 2002; Ling et al., 2002, 2006). During critical periods of embryonic development (E 10.5), maternal exposure to low concentrations of LPS in mice impacts microglial activation and DA neuron survival in offspring that persists into adulthood (Carvey et al., 2003; Ling et al., 2006). Several of these reports indicate that due to immunological perturbation during critical periods of development (Ling et al., 2006) or aging and sentience (Godbout et al., 2005), microglia can become primed, where additional stimuli result in an exaggerated and prolonged pro-inflammatory response that enhances neuron damage. Thus, not only can microglia induce neuron damage, they can become persistently activated to produce continuous and uncontrolled neurotoxicity that fails to reside after the instigating stimulus has dissipated.

Several lines of evidence suggest that adult microglia can also become chronically activated from a single stimulus in the absence of any predispositioning event or aging. For example, chronic microglial activation continues years after brief MPTP exposure in humans (Langston et al., 1999) and primates (McGeer et al., 2003) through a process called reactive microgliosis. Reactive microgliosis is defined by the microglial activation that occurs in response to neuronal damage. This microglial activation is then toxic to neighboring neurons, which causes further microglial activation and a self-propelling progressive cycle of inflammation and neuron damage. Regardless of the class of instigating stimuli (pro-inflammatory toxin or neuronal death) the microglial pro-inflammatory response to neuron damage can drive the progressive inflammation and cumulative loss of neurons over time (Block and Hong, 2005). However, neuroinflammation and microglial activation is not always deleterious (Glezer et al., 2006; Neumann et al., 2006; Simard and Rivest, 2006; Simard et al., 2006; Sriram et al., 2006). Thus, the identification of the stimuli and mechanisms responsible for progressive microglial activation and associated continuous neuron damage is essential to understand the etiology and pathology of neurodegenerative diseases.

Here, we are the first to test whether a single peripheral LPS exposure in adult mice results in: (1) microglial activation and neuroinflammation that persists long after peripheral events have abated; (2) transfer of peripheral inflammation to the brain through TNFα; (3) delayed and progressive loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra (SN), similar to PD. The results from these studies indicate that a single occurrence of sepsis and peripheral inflammation may result in self-propelling neuroinflammation and progressive DA neurodegeneration through TNFα.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Eight-week male (20–22 g) B6; 129S-Tnfrsf1atm1Imx Tnfrsf1btm1Imx/J (TNFR1/R2−/−, KO) and B6; 129SF2/J (TNFR1/R2+/+, WT), and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). B6; 129S-Tnfrsf1atm1Imx Tnfrsf1btm1Imx/J (TNFR1/R2−/−) mice were lacking both the p55 and p75 TNF receptors and maintained in B6; 129SF2/J background. Therefore, B6; 129SF2/J (TNFR1/R2+/+) mice were used as strain controls of TNFR1/R2−/− mice.

Reagents

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, strain O111:B4) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). The polyclonal antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) was a kind gift from Dr. John Reinhard of Glaxo Wellcome (Research Triangle Park, NC). Rat monoclonal antibody raised against F4/80 antigen was purchased from Serotec (Washington, DC). Rabbit anti-Iba1 antibody was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (1–2Doshomachi 3-Chome Chuo-ku Osaka 540–8605, Japan). Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and MCP-1 ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All other reagents came from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Drug Treatment

Male C57BL/6J, TNFR1/R2−/−, and TNFR1/R2+/+ mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of LPS (5 mg/kg), TNFα (0.25 mg/kg), or vehicle (0.9% saline). The dosage of LPS used (5 mg/kg, i.p.) was based on our previous study of endotoxic shock (Li et al., 2005). However, pilot studies using lower doses of LPS (1–4 mg/kg) showed significant increases in brain TNFα mRNA and protein levels in a graded response (data not shown). Mice were sacrificed at selected time points and tissues (serum, brain, and liver) were used for mRNA, protein, or morphological analyses. Procedures using laboratory animals were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of live animals and approved by IUCAC boards.

Analysis of Neurotoxicity

The loss of dopaminergic neurons was assessed by counting the number of TH-immunoreactive (TH-IR) neurons following immunostaining of brain sections. Twenty-four consecutive brain slices (35 μm thickness), which encompassed the entire SNc, were collected. A normal distribution of the number of TH-IR neurons in the SNc was constructed based on the counts of 24 slices from C57BL/6J mice. Eight evenly spaced brain slices from saline or LPS-injected animals were immunostained with an antibody against TH and counted. The distribution of the cell numbers from each animal was matched with the normal distribution curve to correct for errors resulting from the cutting. Samples were counted in a double-bind manner with stereology equipment, three individuals, and the CAST system. Conclusions were drawn only when the difference was within 5%.

Immmunohistochemistry

Brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and processed for immunostaining as described previously (Qin et al., 2004). Dopaminergic neurons were detected with the polyclonal antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). Microglia was stained with rat monoclonal antibody raised against F4/80 antigen and rabbit anti-Iba1 antibody, respectively. Immunostaining was visualized by using 3,3′-diaminobenzidinge and urea-hydrogen peroxide tablets from Sigma.

Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the mouse brain samples treated with LPS, TNFα, or saline at the selected time points and used for reverse transcription PCR analysis as described previously (Qin et al., 2004). The primer sequences used in this study were as follows: for mouse TNFα, 5′-GAC CCT CAC ACT CAG ATC ATC TTC T-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCT CCA CTT GGT GGT TTG CT-3′ (reverse); for mouse IL-1β, 5′-CTG GTG TGT GAC GTT CCC ATT A-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCG ACA GCA CGA GGC TTT-3′ (reverse); for mouse NF-κB p65 (essential modulator), 5′-GGC GGC ACG TTT TAC TCT TT-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCG TCT CCA GGA GGT TAA TGC-3′ (reverse); for mouse β-actin, 5′-GTA TGA CTC CAC TCA CGG CAA A-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGT CTC GCT CCT GGA AGA TG-3′ (reverse). The SYBR green DNA PCR kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used for real-time PCR analysis. The relative differences in expression between groups were expressed using cycle time (Ct) values normalized with β-actin, and relative differences between control and treatment groups were calculated and expressed as relative increases setting control as 100%.

TNFα and MCP-1 Assay

Frozen livers and brains were homogenized in 100 mg tissue/mL cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 0.25 M sucrose, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) and one tablet of Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets/10 mL (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Samples were centrifuged at 100,000g for 40 min. Supernatant was collected for protein assay using the BCA protein assay reagent kit (PIERCE, Milwaukee, WI). The levels of TNFα in livers, sera, and brains and MCP-1 in brains were measured with TNFα and mouse JE/MCP-1 commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), as described previously (Gu et al., 1998).

Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and statistical significance was assessed with an ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's t test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

TNFα Response to Systemic LPS Administration

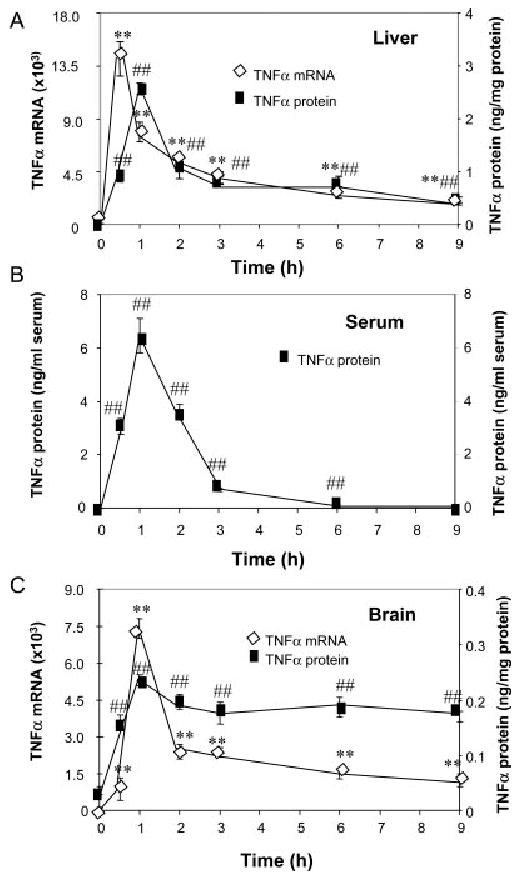

To better understand the effects of systemic LPS on brain inflammation, we administered a single dose of LPS (5 mg/kg) i.p. to male C57BL/6 mice and followed liver, serum, and brain TNFα expression over time. LPS increased liver TNFα mRNA 140-fold that peaked within 30 min. This was followed by liver TNFα protein increase of ∼29-fold that peaked at 60 min. Serum TNFα protein increased from 0 to ∼6.452 ng/mL at 60 min after LPS treatment (see Fig. 1). Brain showed an increase in TNFα mRNA (7,336%) and protein levels (653%) that both peaked at 60 min. Thus, while TNFα protein levels in response to systemic LPS peaked in the liver, serum, and brain at 1 h, brain TNFα mRNA synthesis occurred shortly after liver TNFα mRNA synthesis, very likely after the TNFα protein was able to enter the brain. These results support that liver-derived TNFα was the predominant source of the immediate TNFα response to systemic LPS (1-h post treatment) in the liver, serum, and brain, which then initiated the synthesis of TNFα in the brain.

Fig. 1.

Effects of LPS treatment on liver, plasma, and brain TNFα. Male C57BL/6 mice were treated with saline or LPS (5 mg/kg) i.p. injection. At different time points following LPS or saline injection, mice were sacrificed and brain extracts, liver extracts, and serum were prepared as described in methods. Analysis of TNFα mRNA and protein was conducted via real time RT-PCR and ELISA. (A) LPS rapidly increases liver TNFα mRNA and TNFα protein. (B) Serum TNFα protein is increased after LPS treatment. (C) Brain TNFα mRNA and TNFα protein are increased by LPS. The results are the means ± SEM of two experiments performed with five mice each time point. **P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline controls in TNFα mRNA data. ##P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline controls in TNFα protein data.

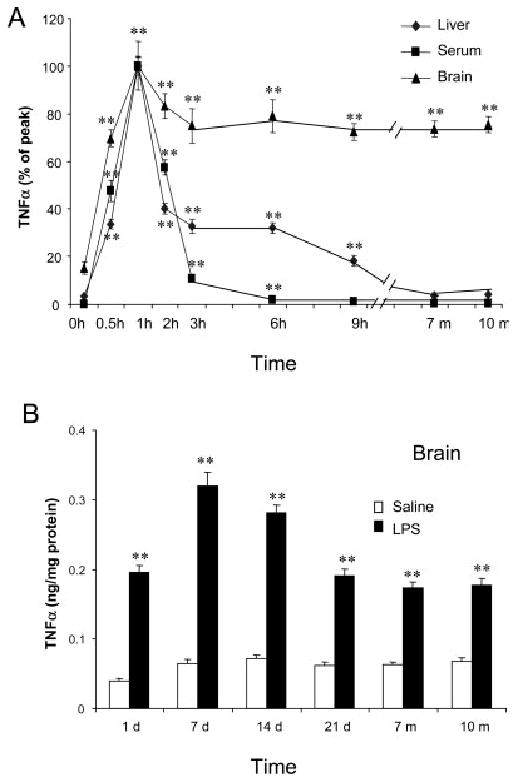

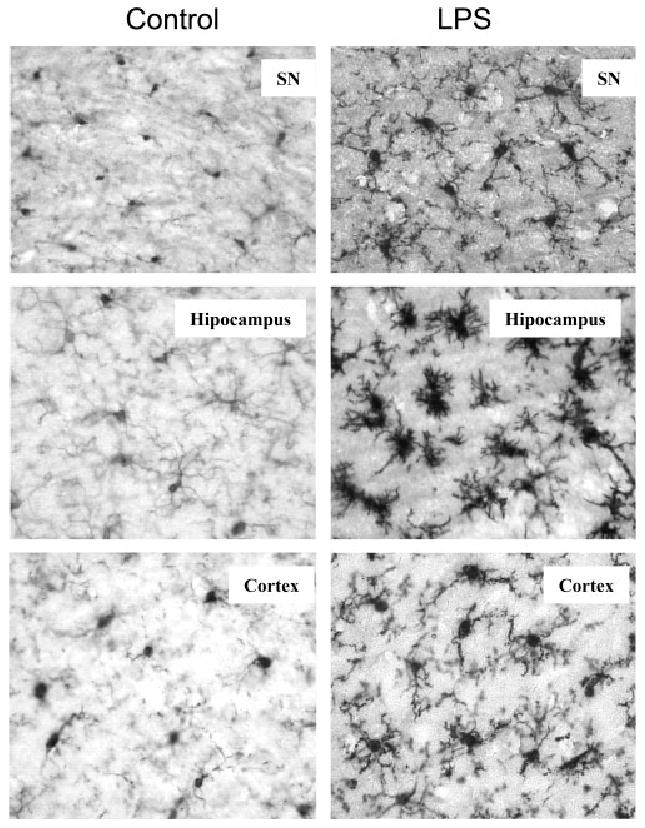

We also examined the long-term effects of systemic LPS injection from several hours until 10-months post treatment. Interestingly, serum TNFα declined to saline control levels by 9 h (Figs. 1B, 2A). In liver, TNFα protein levels declined to 18% of peak values by 9 h after LPS (Figs. 1A, 2A). Surprisingly, TNFα protein remained elevated in brain. At 1 week after LPS treatment TNFα levels were elevated in brain to ∼319 ±20 pg/mg protein compared to control values of 65 ±5 pg/mg protein, a 490% increase similar to the 1-h peak induction. TNFα protein remained elevated at 14 days, 21 days, and even 10 months after LPS treatment (Fig. 2B). In addition, 3 h after LPS treatment staining of microglia in cortex, hippocampus, and SN showed microglia with enlarged cytoplasm and cell bodies, irregular shape, and intensified Iba1 staining consistent with morphological activation of microglia (see Fig. 3). In summary, these results support an association between early (1–9 h) TNFα production in the liver and blood, with chronic (10 months) microglial activation in the brain.

Fig. 2.

Single LPS injection caused long-lasting elevated level of TNFα protein in mouse brain. LPS (5 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally in male C57BL/6 mice. At different time points following LPS or saline injection, mice were sacrificed and brain extracts, liver extracts, and serum were prepared as described in methods. (A) Comparison of time course changes in TNFα protein in liver, serum and brain. Each tissue is adjusted to set peak values as 100%. Note that the liver and serum peak and decline in parallel, whereas, the brain remains elevated for at least 10 months. (B) Long term time course of LPS induced increases in TNFα protein in brain. TNFα levels peaked at 1 h and remained elevated for 10 months. The results are the means ± SEM of two experiments performed with five mice each time point.**P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline controls.

Fig. 3.

Immunocytochemical analysis of microglia. C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed 3 h following saline or LPS (5 mg/kg) i.p. injection. Brain sections were immnostained with Iba1 specific microglial antibody. Activated microglia in substantia nigra, hippocampus and cortex were shown by increased cell size, irregular shape, and intensified Iba1 staining in LPS-treated mouse brains. The images are from one experiment that is representative of three separate experiments.

TNFα Mediates Neuroinflammation in Response to Systemic LPS and TNFα Administration

Studies indicate that TNFα is transported into brain (Pan and Kastin, 2001; Pan et al., 2006) and that TNFα receptors are critical for transport of the TNFα protein from the periphery, across the blood brain barrier, and into the brain (Pan and Kastin, 2002). To test the role of systemic TNFα on inflammation in the brain, we administered a single dose of LPS (5 mg/kg) i.p. or TNFα (0.25 mg/kg) i.p. to male wild type B6:129SF2/J mice (WT) or male mice deficient in the TNF Type 1 and Type 2 receptors (TNFR-KO). TNFα expression (brain, liver, and serum) and the up regulation of other pro-inflammatory genes (IL-1β, NFκB, and MCP-1) in the brain were determined.

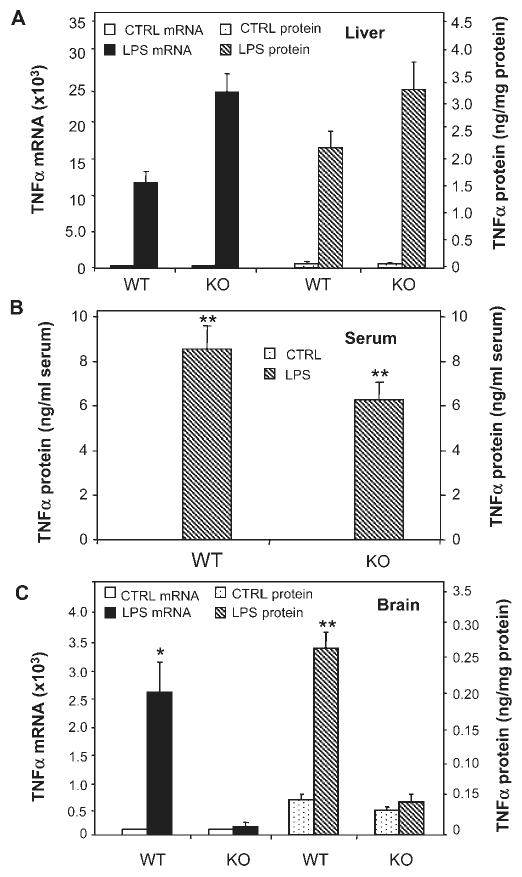

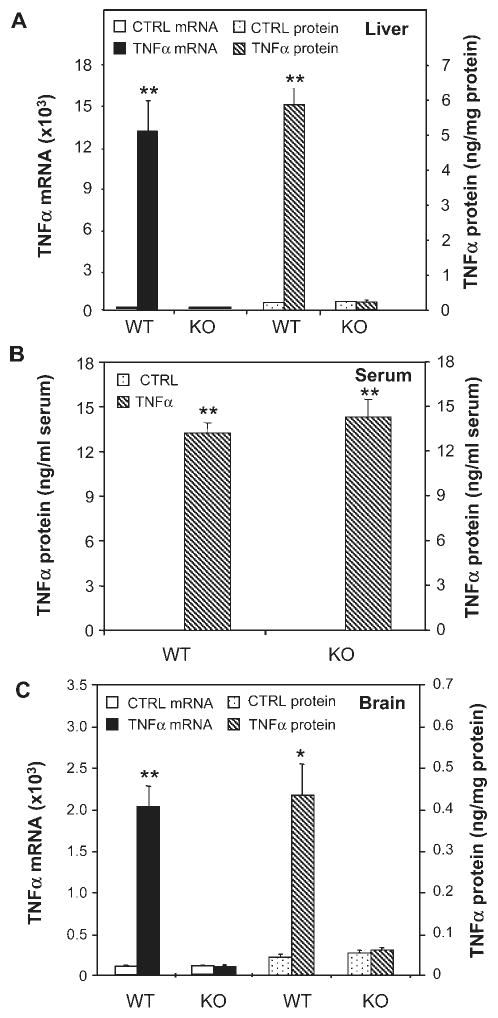

Systemic LPS treatment increased TNFα mRNA and protein in the liver of both WT and TNFR-KO as expected, as LPS triggers an immune response independent of TNFα receptors (Fig. 4A). LPS increased serum levels of TNFα in both WT and TNFR-KO mice. However, brain TNFα mRNA and protein increased only in the WT, but not in TNFR-KO mice, indicating that TNFα receptors are necessary for peripheral LPS to cause brain TNFα mRNA and protein production (Fig. 4C). In a separate experiment, similar to Fig. 3, WT mice showed increased Iba1 (a specific marker for microglia) staining in several brain regions, such as SN, hippocampus, and cortex (images not shown) at 2-h post LPS-treatment. Iba1-IR cells showed increased cell size, irregular shape, and intensified Iba1 staining consistent with morphological changes in activated microglia. Iba1-IR cells in saline controls in WT mice showed resting microglial morphology. However, TNFR-KO animals did not show increased TNFα mRNA or protein synthesis in the brain (Fig. 4C). These findings indicate that TNFα receptors are essential for systemic LPS administration to cause activation of microglia and TNFα synthesis within brain.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of LPS-induced changes in TNFα in TNFR1/R2+/+ (WT) and TNFR1/R2−/− (KO) mice. TNFα mRNA and protein were measured 1 h after saline or LPS (5 mg/kg) i.p. injection. (A) LPS activated liver TNFα mRNA (left legend-solid bars) and TNFα protein (right legend-striped bars) in both wild type (WT) mice and mice lacking TNFα receptors (KO). (B) Serum TNFα protein is elevated by LPS in both WT and KO mice. (C) TNFα mRNA and protein was elevated in WT mice, but not in KO mice. These results indicate that TNFα receptors in brain are essential for LPS induced elevations of brain TNFα, but not for LPS induced elevations of liver TNFα. The results are the means ± SEM of two independent experiments performed with six mice for each treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline controls.

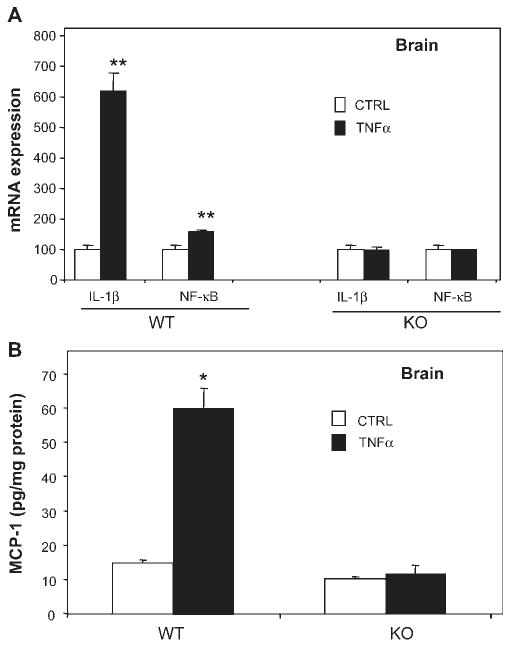

To confirm the role of systemic TNFα in brain inflammation, WT and TNFR-KO mice were treated with TNFα (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.). TNFα treatment resulted in a 132-fold increase in liver TNFα mRNA and a 27-fold increase in liver TNFα protein in WT, but not in TNFR-KO mice (Fig. 5A). The injection of TNFα increased serum levels of TNFα in both WT and TNFR-KO (Fig. 5B). Importantly, systemic TNFα injection induced brain TNFα mRNA and protein in WT, not in TNFR-KO mice (Fig. 5C). Further, TNFα induced brain synthesis of other pro-inflammatory factors, such as monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) as well as NF-κB p65 subunit, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) in WT mice. However, TNFα failed to induce production of the pro-inflammatory factors in TNFR-KO mice (see Fig. 6). Thus, systemic TNFα induces pro-inflammatory cytokine production in brain, serum, and liver, as well as induces brain microglial activation.

Fig. 5.

Effects of systemic TNFα on liver, serum and brain TNFα in TNFR1/R2+/+ (WT) and TNFR1/R2−/− (KO) mice. Animals were sacrificed 1 h following saline or TNFα (0.25 mg/kg) i.p. injection. TNFα mRNA and protein was measured via real time RT-PCR and ELISA. (A) Wild type mice show a marked increase in liver TNFα mRNA (solid bars-left legend) and protein (striped bars-right legend) 1 h after TNFα treatment, but not TNFR1/R2 KO mice. (B) All mice injected with TNFα show increased serum levels of TNFα. (C) In wild type mice systemic TNFα injection markedly increases brain TNFα mRNA (solid bars-left legend) and protein (striped bars-right legend), but not TNFR1/R2 knock out mice. The results are the means ± SEM of two independent experiments performed with six mice for each treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline controls.

Fig. 6.

Systemic TNFα increases IL-1β, NF-κB, and MCP-1 expression in TNFR1/R2+/+ (WT) mice. TNFR1/R2+/+ (WT) and TNFR1/R2−/− (KO) mice were injected with saline or TNFα (0.25 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. Brain mRNA expression of IL-1β and NF-κB-p65 and MCP-1 protein content were measured using real-time PCR and ELISA 1 h following saline or TNFα treatment. (A) Brain mRNA expression of IL-1β and NF-κB-p65 is increased by systemic TNFα in wild type mice, but not in TNFα receptor double KO mice. (B) Systemic TNFα administration increases brain MCP-1 protein in WT mice, but not in TNFR-KO mice. The results are the means ± SEM of two independent experiments performed with six mice for each treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, compared to the corresponding saline control mice.

A comparison of TNFα and LPS indicates these two inflammatory activators are remarkably similar. Our findings suggest that systemic LPS acts by inducing TNFα synthesis in the liver to increase serum TNFα, which then activates brain microglia to induce TNFα, other cytokines, and neuroinflammatory protein synthesis. Taken together, these findings suggest that an acute systemic injection of LPS or TNFα activates brain microglia through TNFα receptors that initiate sustained activation of brain cytokine synthesis and neuroinflammation.

Peripheral Inflammation Induces a Delayed and Progressive Loss of Dopaminergic Neurons in the Substantia Nigra

The substantia nigra (SN) is densely populated with microglia (Kim et al., 2000; Lawson et al., 1990) and it is hypothesized that this brain region is particularly susceptible to inflammatory insult. To discern the effects of chronic neuroinflammation (sustained increase in brain TNFα for at least 10 months) on neuron survival in the SN, we measured the number of dopamine neurons, as indicated by the number of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive (TH-IR) cells within the SN, after a single LPS i.p. treatment. Previous reports using intranigral injection of LPS demonstrated that the LPS-induced decline of TH-IR cells is due to cell loss, as evidenced by a decline in the over-all number of neurons in the SN (Gao et al., 2002). As shown in Fig. 7, LPS injection caused a delayed and progressive loss of nigral TH-IR neurons. Comparison of the number of nigral TH-IR neurons between the LPS-treated and saline-treated mice showed no significant loss of TH-IR neurons within the first 4 months after LPS injection (Fig. 7A). However, significant loss of TH-IR neurons started to manifest between 7 and 10 months after LPS treatment. At 7 months, a 23% loss was observed. The LPS-induced loss of nigral TH-IR neurons further progressed over time and a 47% loss was shown at 10 months (Fig. 7A). Using double labeled (TH-IR and NeuN-IR) staining, we have previously reported that inflammation-induced loss of TH-IR cells in the nigra represents neuronal death, rather a down regulation of TH expression (Gao et al., 2002). Changes in TH-IR cells were more pronounced in SN than in the adjacent ventral tegmental area (VTA) DA neurons (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, staining for microglia using F4/80 antibody indicated that the SN contains much more microglia than the adjacent VTA (Fig. 7C). Cell loss in other brain regions was not determined. Thus, the SN may be inherently susceptible to inflammatory insult when compared to other regions of the basil ganglia due to the presence of increased microglia. These studies support the hypothesis that an acute increase in systemic TNFα activates neuroinflammatory processes within brain that are sustained for long periods, which leads to delayed and progressive degeneration of DA neurons.

Fig. 7.

Delayed and time-dependent loss of nigral dopaminergic neurons following LPS i.p. injection. Male C57BL/6 mice were treated with saline or LPS (5 mg/kg, i.p.) and then maintained under normal conditions for the indicated time points. Mice were sacrificed and brain sections (35 mm thick) were cut through the nigral complex. After immunostaining with TH antibody, the number of TH-IR neurons in the SN was counted as described in methods. Results are expressed as percentage of the corresponding saline controls. (A) Number of TH-IR neurons in the SN of control and LPS-treated mice at different time points. (B) Visualization of TH-IR neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of saline and LPS-treated animals at 10 months. (C) F4/80-Immunohistochemistry for microglia within the SN and VTA of saline and LPS treated animals at 10 months. Note the high density of F4/80-IR microglia in the substantia nigra associated with the loss of dopaminergic neurons in mice treated with LPS. **P < 0.01, compared to the saline controls (n = 8–10 per time point).

Discussion

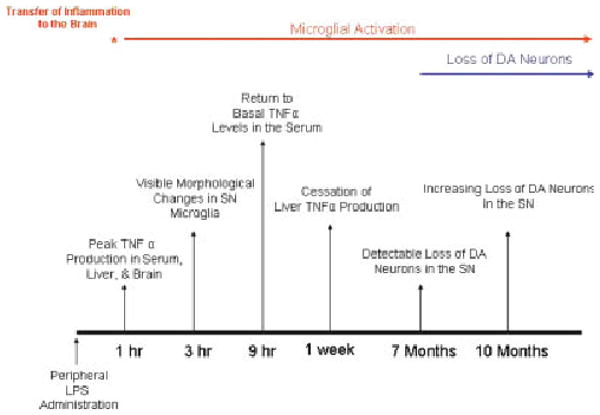

The mechanisms responsible for the progressive loss of DA neurons in PD are poorly understood. Here, we are the first to show that a single exposure to systemic inflammation transfers to the brain and initiates self-propelling neuroinflammation that persists for 10 months, which results in the progressive loss of DA neurons in the SN (see Fig. 8). Specifically, we investigated three aspects of peripheral LPS administration: the role of TNFα in the transfer of systemic inflammation to the brain, the duration of neuroinflammation, and the neurotoxic consequences for DA neurons in the SN.

Fig. 8.

Systemic LPS causes chronic microglial activation and progressive dopaminergic neurotoxicity. This figure chronologically depicts the pro-inflammatory profiles in the periphery and the brain in response to LPS and the consequences for dopaminergic neuron survival. TNFα levels peaked in serum, liver, and the brain at 1 h, indicating that transfer of inflammation from the periphery to the brain was rapid. Changes in microglia morphology indicative of activation were present at 3 h. However, while peripheral inflammation (serum and liver TNFα production) had subsided by 9 h (serum) and 1 week (liver) after LPS treatment, brain TNFα and microglial activation remained elevated for up to 10 months. Interestingly, significant loss of dopaminergic neurons was first detected only at 7 months after treatment and increased in severity at 10 months after LPS exposure. These events document the development of inflammation in the substantia nigra in response to peripheral LPS administration and the consequent initiation of delayed and progressive dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

Peripheral Inflammation Causes Chronic Neuroinflammation Through TNFα

In the current study, we demonstrate that a single intraperitoneal LPS injection results in TNFα production in the periphery, which initiates brain TNFα production (mRNA and protein) in the brain that continues for months after the systemic source of TNFα has abated. It was previously reported that liver is the major source for the circulating TNFα after a single systemic LPS injection, due to activation of kupffer cells, the resident macrophage-like cells in the liver (Kumins et al., 1996). These cytokines are then released into the blood and induce inflammation throughout the body (Crews et al., 2006). Here, we found that liver and serum TNFα were elevated at early time points, but declined over time to return to basal levels by 1 week and 9 h, respectively. Remarkably, TNFα levels remained elevated in the brain for up to 10 months, long after liver and serum levels had subsided. Further, immunohistochemical analysis of brain sections showed that microglia was activated in several brain regions, such as the SN, hippocampus, and cortex. Previous reports have shown that a single exposure to MPTP, a toxin selective for DA neurons, in humans (Langston et al., 1999) and monkeys (McGeer et al., 2003) resulted in microglial activation that persisted years after the brief exposure. Earlier studies investigating the long-term effects of systemic LPS exposure in utero has shown that low levels of systemic inflammation must occur during a critical window of development in order for the long lasting, pro-inflammatory changes in the brain to occur (Carvey et al., 2003; Ling et al., 2002). Our current work indicates that a single pro-inflammatory event in the periphery can induce chronic, self-propelling neuroinflammation outside of the embryonic critical period and in the adult brain.

It is well-documented that in the normal condition, very little peripheral LPS enters to the brain due to the poor passage through the blood brain barrier (Nadeau and Rivest, 1999). Thus, the LPS-induced neuroinflammation is likely an indirect effect. In an effort to understand how chronic neuroinflammation was transferred from the periphery to the brain, we administered TNFα peripherally and found that both systemic TNFα and LPS administration increased the expression of brain pro-inflammatory factors (TNFα, MCP-1, IL-1β, and NF-κB p65) in a similar pattern. Further, TNFR1/R2−/− mice failed to show brain neuroinflammation in response to systemic LPS or systemic TNFα, supporting that TNFα was critical for the transfer of inflammation from the periphery to the CNS. This is consistent with other studies demonstrating that systemic cytokines mediate the effects of peripheral inflammation on the brain. For example, TNFα and other systemic cytokines are reported to mimic several behavioral effects of systemic LPS (Berkenbosch et al., 1987; Bernardini et al., 1990; Sapolsky et al., 1987; Sharp et al., 1989). Thus, systemic cytokines are critical for CNS effects in response to peripheral immune activation.

Here, we are the first to show chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration a single injection of LPS. Currently, the detailed mechanisms of this progressive neuroinflammation are unknown. However, we speculate that the initial entry of the pro-inflammatory factors, such as TNFα to the brain will cause the activation of microglia to produce more inflammatory factors, which may cause neuronal death. Upon exposure to TNFα, microglia are well known to synthesize and secrete TNFα (Rivest et al., 2000). Thus, this initial damage may then result in reactive microgliosis, causing the release of additional pro-inflammatory factors to begin a self-propelling and a vicious cycle of neuronal damage. We propose that reactive microgliosis may underlie the progressive and long-lasting neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration of numerous neurodegenerative diseases (Block and Hong, 2005).

Peripheral Inflammation Causes Progressive Dopaminergic Neurotoxicity

Inflammation is implicated as a neurodegenerative stimulus (Maurizi, 2002) and DA neurons in the SN are thought to be more susceptible to inflammation when compared to other neuronal subtypes and other brain regions (Block and Hong, 2005; Carvey et al., 2003; Gao et al., 2002; Ling et al., 2002). Microglial activation has been shown to induce the selective loss of DA neurons in response to multiple stimuli (Block et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005), including LPS (Gao et al., 2002; Ling et al., 2002, 2004a,b, 2006). Additionally, the SN contains 4.5 times as many microglia when compared to other brain regions (Kim et al., 2000), making this region particularly susceptible to inflammatory insult. In the current study, we have stained the SN for microglia and document that there are visibly more microglia in the SN, when compared to the VTA and other brain regions (see Fig. 7), helping to explain why global neuroinflammation can result in selective damage. Previously, it has been shown that a single injection of the selective dopaminergic neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), results in chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurotoxicity in humans (Langston et al., 1999) and monkeys (McGeer et al., 2003), where the mechanisms of microglial activation and progressive toxicity are poorly defined. Here, we show that a single systemic administration of LPS results in significant loss of DA neurons beginning at 7-months post treatment (23% loss of TH-IR neurons) and increasing in severity with time to a 47% loss at 10-months post treatment. Thus, we are the first to show that a single pro-inflammatory stimulus from the periphery in the adult mouse results in delayed and progressive loss of DA neurons in the SN (over months), similar to what occurs in PD. This is consistent with a previous report of a single human case study where accidental peripheral administration of LPS was associated with later onset of PD (Niehaus, 2003). The delayed onset, progressive nature, and long-lasting DA neuronal degeneration after a single injection of LPS shown in this study suggests a clinical implication for the link between peripheral inflammation and neuroinflammation. Thus, it would be interesting to determine epidemiologically whether there is a link between patients surviving septic shock and the incidence of PD.

Several studies indicate that pro-inflammatory events occurring peripherally can influence neurotoxicity. The majority of previous reports demonstrate that systemic inflammation can amplify an inflammatory stimulus and consequent neuronal damage. For example, systemic administration of LPS enhanced motor neuron degeneration in animal models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis at 6 months (Nguyen et al., 2004), but no direct toxic effect of systemic LPS alone was reported. Systemic exposure to LPS in the neonate was also shown to significantly amplify neuronal death associated with ischemic insult (Lehnardt et al., 2003). Interestingly, it is suggested that peripheral inflammation could be protective, as one study has shown that neuroinflammation induced by intrastriatal injection of endotoxin could be blocked by systemic LPS administration, where the protection was mediated through LPS-induced plasma corticosterone (Nadeau and Rivest, 2002). In the current study, we demonstrate that a high dose of systemic LPS (5 mg/kg) can actively induce persistent inflammation and progressive neurotoxicity over 10 months in the adult animal. Thus, the effects of peripheral inflammation on neuron survival may depend upon several factors, such as brain region examined, length of time investigated to allow cumulative effects, age of exposure to the inflammagen, presence of systemic TNFα, and severity of the inflammatory stimuli tested.

In summary, our study supports that LPS activates cells in the liver to produce TNFα, which is distributed in the blood and transferred to the brain through TNFα receptors to induce the synthesis of additional TNFα and other pro-inflammatory factors, creating a persistent and self-propelling neuroinflammation that induces delayed and progressive loss of DA neurons in SN of adult animals. This work offers strong support for the premise that inflammation is both an initiating stimulus and a self-propelling mechanism of progressive neurondegeneration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Jenny Ting, John Gilmore, and Richard Mailman for their scholarly comments and Melissa Mann for manuscript preparation.

Grant sponsors: National Institute of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Berkenbosch F, van Oers J, del Rey A, Tilders F, Besedovsky H. Corticotropin-releasing factor-producing neurons in the rat activated by interleukin-1. Science. 1987;238:524–526. doi: 10.1126/science.2443979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini R, Kamilaris TC, Calogero AE, Johnson EO, Gomez MT, Gold PW, Chrousos GP. Interactions between tumor necrosis factor-a, hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, and adrenocorticotropin secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 1990;126:2876–2881. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-6-2876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Hong JS. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: Multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76:77–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Wu X, Pei Z, Li G, Wang T, Qin L, Wilson B, Yang J, Hong JS, Veronesi B. Nanometer size diesel exhaust particles are selectively toxic to dopaminergic neurons: The role of microglia, phagocytosis, and NADPH oxidase. FASEB J. 2004;18:1618–1620. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1945fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvey PM, Chang Q, Lipton JW, Ling Z. Prenatal exposure to the bacteriotoxin lipopolysaccharide leads to long-term losses of dopamine neurons in offspring: A potential, new model of Parkinson's disease. Front Biosci. 2003;8:S826–S837. doi: 10.2741/1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CA, Gilbert DL. Production of superoxide anions by a CNS macrophage, the microglia. FEBS Lett. 1987;223:284–288. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Bechara R, Brown LA, Guidot DM, Mandrekar P, Oak S, Qin L, Szabo G, Wheeler M, Zou J. Cytokines and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:720–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Jiang J, Wilson B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Liu B. Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: Relevance to Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2002;81:1285–1297. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons HM, Dragunow M. Microglia induce neural cell death via a proximity-dependent mechanism involving nitric oxide. Brain Res. 2006;1084:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glezer I, Lapointe A, Rivest S. Innate immunity triggers oligodendrocyte progenitor reactivity and confines damages to brain injuries. FASEB J. 2006;20:750–752. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5234fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbout JP, Chen J, Abraham J, Richwine AF, Berg BM, Kelley KW, Johnson RW. Exaggerated neuroinflammation and sickness behavior in aged mice following activation of the peripheral innate immune system. FASEB J. 2005;19:1329–1331. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3776fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu L, Okada Y, Clinton SK, Gerard C, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Rollins BJ. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduces atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Mol Cell. 1998;2:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WG, Mohney RP, Wilson B, Jeohn GH, Liu B, Hong JS. Regional difference in susceptibility to lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity in the rat brain: Role of microglia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6309–6316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06309.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumins NH, Hunt J, Gamelli RL, Filkins JP. Partial hepatectomy reduces the endotoxin-induced peak circulating level of tumor necrosis factor in rats. Shock. 1996;5:385–388. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston JW, Forno LS, Tetrud J, Reeves AG, Kaplan JA, Karluk D. Evidence of active nerve cell degeneration in the substantia nigra of humans years after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine exposure. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:598–605. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199910)46:4<598::aid-ana7>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson LJ, Perry VH, Dri P, Gordon S. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SC, Liu W, Dickson DW, Brosnan CF, Berman JW. Cytokine production by human fetal microglia and astrocytes. Differential induction by lipopolysaccharide and IL-1 β. J Immunol. 1993;150:2659–2667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnardt S, Massillon L, Follett P, Jensen FE, Ratan R, Rosenberg PA, Volpe JJ, Vartanian T. Activation of innate immunity in the CNS triggers neurodegeneration through a Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8514–8519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432609100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Liu Y, Tzeng NS, Cui G, Block ML, Wilson B, Qin L, Wang T, Liu B, Liu J, et al. Protective effect of dextromethorphan against endotoxic shock in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z, Chang QA, Tong CW, Leurgans SE, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Rotenone potentiates dopamine neuron loss in animals exposed to lipopolysaccharide prenatally. Exp Neurol. 2004a;190:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z, Gayle DA, Ma SY, Lipton JW, Tong CW, Hong JS, Carvey PM. In utero bacterial endotoxin exposure causes loss of tyrosine hydroxylase neurons in the postnatal rat midbrain. Mov Disord. 2002;17:116–124. doi: 10.1002/mds.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z, Zhu Y, Tong CW, Snyder JA, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Progressive dopamine neuron loss following supra-nigral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infusion into rats exposed to LPS prenatally. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:499–512. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling ZD, Chang Q, Lipton JW, Tong CW, Landers TM, Carvey PM. Combined toxicity of prenatal bacterial endotoxin exposure and postnatal 6-hydroxydopamine in the adult rat midbrain. Neuroscience. 2004b;124:619–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Gao HM, Wang JY, Jeohn GH, Cooper CL, Hong JS. Role of nitric oxide in inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:318–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurizi CP. Postencephalitic Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on Guam and influenza revisited: Focusing on neurofibrillary tangles and the trail of tau. Med Hypotheses. 2002;58:198–202. doi: 10.1054/mehy.2000.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer EG, Klegeris A, McGeer PL. Inflammation, the complement system and the diseases of aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(Suppl 1):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, Schwab C, Parent A, Doudet D. Presence of reactive microglia in monkey substantia nigra years after 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine administration. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:599–604. doi: 10.1002/ana.10728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss DW, Bates TE. Activation of murine microglial cell lines by lipopolysaccharide and interferon-γ causes NO-mediated decreases in mitochondrial and cellular function. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:529–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau S, Rivest S. Effects of circulating tumor necrosis factor on the neuronal activity and expression of the genes encoding the tumor necrosis factor receptors (p55 and p75) in the rat brain: A view from the blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1449–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau S, Rivest S. Endotoxemia prevents the cerebral inflammatory wave induced by intraparenchymal lipopolysaccharide injection: Role of glucocorticoids and CD14. J Immunol. 2002;169:3370–3381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann J, Gunzer M, Gutzeit HO, Ullrich O, Reymann KG, Dinkel K. Microglia provide neuroprotection after ischemia. FASEB J. 2006;20:714–716. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4882fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MD, D'Aigle T, Gowing G, Julien JP, Rivest S. Exacerbation of motor neuron disease by chronic stimulation of innate immunity in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1340–1349. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4786-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MD, Julien JP, Rivest S. Innate immunity: The missing link in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:216–227. doi: 10.1038/nrn752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus I. Lippopolysaccharides induce inflammation-mediated neurodeheneration in the substantia nigra and the cerebral cortex (A case report). AD/PD 6th International Conference; Bologna, Italy. 2003. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Ding Y, Yu Y, Ohtaki H, Nakamachi T, Kastin AJ. Stroke upregulates TNFα transport across the blood-brain barrier. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Kastin AJ. Increase in TNFα transport after SCI is specific for time, region, and type of lesion. Exp Neurol. 2001;170:357–363. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Kastin AJ. TNFα transport across the blood-brain barrier is abolished in receptor knockout mice. Exp Neurol. 2002;174:193–200. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polazzi E, Contestabile A. Reciprocal interactions between microglia and neurons: From survival to neuropathology. Rev Neurosci. 2002;13:221–242. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2002.13.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Liu Y, Wang T, Wei SJ, Block ML, Wilson B, Liu B, Hong JS. NADPH oxidase mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity and proinflammatory gene expression in activated microglia. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1415–1421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivest S, Lacroix S, Vallieres L, Nadeau S, Zhang J, Laflamme N. How the blood talks to the brain parenchyma and the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus during systemic inflammatory and infectious stimuli. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;223:22–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R, Rivier C, Yamamoto G, Plotsky P, Vale W. Interleukin-1 stimulates the secretion of hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor. Science. 1987;238:522–524. doi: 10.1126/science.2821621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada M, Kondo N, Suzumura A, Marunouchi T. Production of tumor necrosis factor-a by microglia and astrocytes in culture. Brain Res. 1989;491:394–397. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp BM, Matta SG, Peterson PK, Newton R, Chao C, McAllen K. Tumor necrosis factor-a is a potent ACTH secretagogue: Comparison to interleukin-1 b. Endocrinology. 1989;124:3131–3133. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-6-3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard AR, Rivest S. Neuroprotective properties of the innate immune system and bone marrow stem cells in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:327–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, Julien JP, Rivest S. Bone marrow-derived microglia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2006;49:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K, Matheson JM, Benkovic SA, Miller DB, Luster MI, O'Callaghan JP. Deficiency of TNF receptors suppresses microglial activation and alters the susceptibility of brain regions to MPTP-induced neurotoxicity: Role of TNF-α. FASEB J. 2006;20:670–682. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5106com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XF, Block ML, Zhang W, Qin L, Wilson B, Zhang WQ, Veronesi B, Hong JS. The role of microglia in paraquat-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:654–661. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang T, Pei Z, Miller DS, Wu X, Block ML, Wilson B, Zhou Y, Hong JS, Zhang J. Aggregated α-synuclein activates microglia: A process leading to disease progression in Parkinson's disease. FASEB J. 2005;19:533–542. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2751com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]