Abstract

While the literature widely acknowledges the importance of social support to the health, well-being and performance of older adults, little is known about the way in which occupational conditions affect older employees’ access to social support over time and whether these effects are maintained after retirement. Accordingly, in the current study we examine the degree to which work hours have longer term effects on the amount and type of support older individuals receive from intimate coworkers, family and non-work friends, and whether these effects are attenuated or intensified for those who retire. Longitudinal data were collected from a random sample of members of nine unions, 6 months prior to their retirement eligibility (T1) and approximately one year after Time 1 (T2). Our findings indicate that while retirement attenuates the positive association between Time 1 work hours and subsequent coworkers' support as well as the negative relationship between Time 1 work hours and subsequent non-work friends support, retirement fails to attenuate the negative effect of Time 1 work hours on subsequent family support. Policy implications are discussed.

Keywords: Work hours, Older adults, Retirement, Social support

A growing body of literature suggests that social support -- a key coping resource that protects employees from the harmful impact of stressful job situations (House, Landis & Umberson 1988) and generally enhances employees’ health, well-being (Parasuraman, Greenhaus & Granrose, 1992) and performance (Chambel & Curral, 2005) -- may, for a number of reasons, be particularly important for older individuals (see Antonucci, Fuhrer & Jackson, 1990; Maurer, 2001; Siebert, Mutran & Reitzes, 1999). First, as people age, they experience decreased energy and sleeping difficulties (see Jex, Wang & Zarubin, 2007; Smith et al., 1999), which may increase older individuals' dependency on supportive relations in order to maintain both their health and job performance in the face of demanding work conditions (Hansson et al., 1997). Second, age has been found to be associated with a decline in individuals' self-confidence in their ability to learn and develop (see Maurer, 2001), thus potentially increasing the importance of social support from work and outside of work as a means by which to enhance the self-efficacy of older adults (Maurer, 2001; Maurer & Tarulli, 1996). Finally, with the bulk of older workers approaching retirement -- a potentially stressful life event (Hedge, Borman & Lammlein, 2006; Nuttman-Shwartz, 2004) -- supportive relations are likely to serve as an increasingly important resource, facilitating successful coping and adjustment (Kim & Moen, 2002).

These potentially stress-buffering and direct effects of social support on older individuals’ health, emotional well-being and performance have been widely acknowledged. However, research finds that individuals’ access to strong support networks and the support they provide actually diminishes as they age (Kosteniuk & Dickinson, 2003; Shaw et al., 2007). Numerous factors (e.g., death of close family members and friends or residential relocation) likely account for many of the limitations older individuals face in securing the social support that they need (Ikkink & van Tilburg, 1999). Nevertheless, drawing from theorizing in the social psychology of relational exchange (Lawler, 2001; Lawler & Yoon, 1996), we argue that work-related factors, and in particular the combination of workplace demands and retirement, may also play an important role.

The theory of relational cohesion (Lawler & Yoon, 1996) suggests that the accessibility of social resources increases as a function of relational commitment which develops as a result of frequent dyadic exchanges. More specifically, frequent exchange and the relational commitment elicited by it, reduce the level of uncertainty associated with the relationship, extend the types of resources exchanged, and enhance the satisfaction and positive emotions associated with both the exchange partner and the relationship as a whole (Thye, Yoon & Lawler, 2002). Indeed, several experiments clearly demonstrate that repeated exchange with the same others promote perceived cohesion and commitment behavior (e.g., staying in the relation, providing unilateral gifts – both tangible and intangible) (see Lawler, 2001). Moreover, Lawler’s (2001) affect theory of social exchange suggests that the productivity of social exchange, and hence, a partner’s access to social resources, is a function of the degree to which partners perform joint tasks and activities. Such jointness (i.e., nonseparability of individuals' impact on the success or failure of these joint tasks) is the basis for generating strong mutual responsibility and obligation for the emotional and instrumental "products" of the exchange. Overall, this means that an individual's access to social resources is likely to be greater to the extent that the work environment allows, encourages or demands increased exchange. However, it also suggests that an individual’s access to social resources will be more limited to the extent that environmental demands place any restriction on the frequency and productivity of exchanges.

Adopting such perspective, and drawing from the notion that intimate relationships both at work and away from it (i.e., with family and non-work friends) are often the primary sources of emotional and instrumental support in times of need (Iida et al., 2008), we suggest that workplace demands, depending on the degree to which they increase or reduce the frequency and productivity of exchanges with intimate others, are likely to increase or reduce an individuals' access to social support from these intimate others in times of need. Moreover, we suggest that retirement is likely to attenuate any beneficial effect, and amplify any adverse effect, of workplace demands on older individuals’ access to social support. We base this argument on the assumption that retirement is often associated with a redefinition of daily routines and self-image (Hedge, Borman & Lammlein, 2006), a distancing from intimate, work-based exchange partners (Bosse et al., 1990; Bosse et al., 1993), as well as with stressors (e.g., financial, marital) potentially limiting the individuals’ ability to engage in productive exchange with other, non-work intimate others (Moen, Kim & Hofmeister, 2001; Szinovacz & Ekerdt, 1996).

There are numerous occupational demands (“aspects of the work environment that tax employees personal capacities and therefore are associated with certain physiological or psychological costs”; Van den Broeck, Vansteenkiste, De Witte & Lens, 2008: 278) which could serve as an empirical referent for any analysis of support predictors (e.g., workload, work-home interference). However, in the current study we focus on temporal workplace demands. We do so because the number of hours worked is considered to have immediate as well as long term implications on employee physical health, psychological functioning and social relations (Heaphy & Dutton, 2008; Parkes, 1999), thus having the potential to affect individuals' support mobilization both in and outside the workplace over time. Consequently, in the current study we examine the way in which the number of hours older individuals' work affects these individuals' longer-term access to social support from intimate family members, coworkers and non-work friends, and the degree to which these effects may be attenuated or intensified as a function of retirement.

Work hours and older workers’ access to social support

Work hours are widely considered as being detrimental to individuals' ability to engage in productive resource exchange with intimate others outside of work (Pleck, Staines & Lang, 1980; Voydanoff, 2004). This is likely to be especially true in the case of older workers given their increased vulnerability to the harmful physical, psychological and social effects of job demands in general and temporal workplace demands in particular (Hansson et al., 1997; Harrington, 2001). First, long hours at work consume the time needed to meet non-work related demands, such as fulfilling household chores or interacting with family and friends (Voydanoff, 2004). Indeed, the organizational and occupational health literatures suggests that workplace demands such as long working hours are associated with efforts to limit one’s personal, family-related, and service-related obligations (Becker & Moen, 1999; Devoe & Pfeffer, 2007).

Second, research suggests that long work hours may also deplete the resources of worker's close family members in that, given the absence of the worker, a larger share of domestic-related responsibilities fall on them (Major, Klein & Ehrhart, 2002). As they are left to cope with the unmet domestic responsibilities of the worker, close family members are likely to experience physiological and psychological resource drain, leaving them with fewer resources with which to support the individual when he/she is in need (Iida et al., 2008).

Third, longer working hours increases the individual’s potential exposure to emotionally and/or physically draining working conditions, with older workers likely to be more affected by such exposure due to their more limited resource reserves (Hansson et al., 1997). To the degree that such exposure is manifested in the form of negative mood, attitudes and emotions (Geiger-Brown et al., 2004), which might often spill-over (i.e., generate similarities) to employee non-work related social interactions (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000; Voydanoff, 2001), long working hours may further limit older workers’ potential for productive social exchanges. Finally, the potential for productive social exchanges may also be exacerbated to the extent that greater temporal demands increase the risk of short and long-term physiological difficulties and illnesses (see Heaphy & Dutton, 2008; Parkes, 1999), as well as the use of maladaptive behaviors, such as cigarette smoking, alcohol and drug use, and excessive caffeine intake (see Geiger-Brown et al., 2004 for review).

Accordingly, regardless of whether older individuals work increased hours in order to avoid negative consequences (e.g. sanctions imposed by the organization for failure to work overtime) or to enjoy the associated benefits (e.g. improved financial security leading to improved quality of life) (Tucker & Rutherford, 2005), it is still likely that long work hours contribute to the erosion of physical, emotional and temporal resources of older individuals and their families. This bilateral erosion of resources is likely to reduce the productivity and frequency of resource exchanges between older workers and their intimate others outside of work. Accordingly, we suggest that as work hours increase, support resources from non-work sources are likely to be less accessible to older individuals, or in other words:

Hypothesis 1: The number of hours typically worked by older employees is inversely related to the level of support available to them from family members and non-work friends.

However, while long work hours may limit the ability of older employees to invest resources in their close non-work relations, researchers have recognized the positive impact that such temporal workplace conditions may have on the employee’s ability to mobilize support-based resources in the workplace (Hochschild, 1997). According to Hochschild (1997), as working hours increase, employees tend to identify home as a place of stress and unending demands while identifying work as a pleasant place of friendship and support. Moreover, Powell and Foley (1998) suggest that because long work hours are associated with an increase in the frequency and intensity of social contacts in the workplace, they facilitate the formation and intensification of work-based intimate relationships. Put in other terms, this research suggests that by providing increased opportunities for productive resource exchange with others in the workplace, longer working hours may generate higher levels of relational commitment among coworkers, and thus increase employees’ access to work-based social support. Accordingly, Straits (1996) found work hours to increase expressive ties with coworkers, suggesting that increased hours worked may indeed promote opportunities for closer peer relations. Additionally, in their study of junior and senior hospital doctors, Fielden and Pecker (1999) found that longer hours worked by junior doctors may increase accessibility to social support from the work environment, while restricting their access to social support from the home environments. While such findings suggest that the effects of longer work hours on work-based resource mobilization are not limited to strictly older workers, they nevertheless suggest that an older employee’s ability to successfully mobilize support-based resources in the work environment is likely to increase as a function of the number of hours worked. Consequently, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: The number of hours typically worked by older workers is positively related to the level of support available to them from coworkers.

The Moderating Role of Retirement

Still, a question arises as to whether and how retirement may moderate the relationship between temporal workplace demands (prior to retirement) and individual access to support from in and outside the workplace. Research exploring the effect of retirement on work-based relations consistently supports the notion that retirement is associated with the weakening or termination of work-related relationships (Bacharach et al., 2007; Bosse et al., 1990; Bosse et al., 1993). Retirees often occupy new roles, have new needs, and lead a different life-style. On the one hand, such changes may reduce their ability to invest resources in their former coworkers. On the other hand, such changes may also reduce the extent to which they need to rely on work-based support in order to maintain functioning and performance. In this sense, Bosse and colleagues (1990) found that relative to workers, retirees reported fewer coworkers as friends and fewer coworkers as confidents. However, they also found that the greatest difference between workers and retirees was in the use of coworker support. Retirees, almost never talked to former coworkers about problems they were having with retirement, finances, marital, and social problems, unlike workers, who felt more at ease (or had more occasion) to discuss those problems with current coworkers. In other words, although retirees considered former coworkers to be friends, they no longer turned to them for support in stressful situations. Such findings suggest that the weakening of work-based close relationships as a result of retirement may have particularly salient support implications for those individuals who, as a result of long work hours prior to retiring, relied upon coworkers as their primary source of social support.

While the literature generally supports the notion of loss with regard to work-based relations, research regarding the impact of retirement on the quality of non-work-based social relations has been inconclusive. Numerous studies have indicated that retirement increases employee involvement in family life and non-work related friendships (Boose et al., 1990; Kulik, 2001; Szinovacz, 2004; Vinick & Ekerdt, 1991). However, other studies indicate that retirement may generate family tension, disruption and conflict (see Hill & Dorfman, 1982; Moen et al., 2001; Szinovacz & Ekerdt, 1996), and may lead to decline in friendship network and heightened sense of isolation and loneliness (see Alpass & Neville, 2003; Barnes & Parry, 2004; Stevens & van Tilburg, 2000).

In light of these inconsistent findings, researchers have suggested that in order to understand the way by which retirement affect non-work relations, it is important to take into account the pre-retirement job characteristics of retirees (Mayer & Booth, 1996; Szinovacz & Ekerdt, 1996). From a resource ecology perspective (Hobfoll, 2002), individuals who experience resource-eroding circumstances prior to retirement may be more vulnerable to the potential stressors associated with this life transition, and hence may be at greater risk for a further deterioration of resources. And, as noted earlier, in the case of older individuals, longer working hours prior to retirement are likely to generate just such circumstances, depleting personal resources, both emotional and physical (Hockey, 1993; 1997). As a result, relative to those retiring from less temporally-demanding jobs, employees retiring from jobs requiring longer working hours are more likely to start their retirement in a state of resource depletion (Szinovacz, 2006; Mayer & Booth, 1996).

Resource ecology theory and its notion of "loss spirals" (Hobfoll, 2002) suggests that such a state of relative resource depletion often triggers the adoption of inefficient resource conservation strategies (e.g., applying resources in the service of unrealistic future goal attainment or drinking to cope with distress) (Hobfoll, 2002; Demerouti, Bakker & Bulters, 2004). This may ultimately result in even more intensified demands on the individual and a further draining of the personal resources needed in order to invest in and strengthen the quality of non-work support ties (i.e., ties with family members and non-work friends) as an alternative to those work-based sources of support weakened or lost as a function of retirement. Consequently, focusing on the number of hours worked by older employees prior to their retirement, we posit that:

Hypothesis 3: Retirement attenuates the positive relationship between the number of hours typically worked by older employees and the level of support subsequently available to them from coworkers.

Hypothesis 4: Retirement amplifies the inverse relationship between the number of hours typically worked by older employees and the level of support subsequently available to them from family members and non-work friends.

Method

Subjects

The sample for this research was obtained from nine national and local unions representing workers employed in three blue color sectors in the United States: Transportation, Manufacturing and Construction. Survey data were collected from a sample of retirement eligible workers in each of the nine unions. Retirement-eligible workers were defined as those individuals who met their union's criteria for early or full retirement benefits. Because these criteria vary from union to union, some retirement-eligible members in the sample are relatively young. The age of the workers in the sample ranged from 42 to 70 (mean = 56). Each union provided the names, phone numbers and retirement eligibility dates of all of its members eligible for retirement. Survey data were collected at two points in time (T1 and T2) through telephone interviewing, with all participants interviewed approximately 6 months (+/− 2 weeks) prior to their retirement eligibility date (T1) and one year (+/− 2 weeks) after the first interview (T2). The total number of respondents at T1 was 1,279 (out of a target sample of 2,812, an overall response rate of 46%). The number of respondents from each employment sector are as follows: 933 respondents were members of three unions in the transportation employment sector (railroad workers, flight attendants and urban transport workers), 178 respondents were members of two unions in the manufacturing employment sector (unskilled assembly-line operators, semiskilled machine operators and skilled-trades workers), and 168 respondents were members of four unions in the building trades or construction employment sector (electricians, plumbers and painters). Demographic Breakdown of age and gender within each sector is provided in Table 1. Of the 1,279 T1 respondents, 1,122 participated in the T2 survey (dropout rate: 12%). Of the 1,122 observations, 122 were excluded due to missing data on one or more core demographic variables leaving us with a final sample of 1000 observations of which 730 (73%) were males and 270 (27%) were females.

Table 1.

Demographic breakdown of age and gender within each sector (N=1279)

| 1. sector | N | Variable | Mean |

SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 178 | Gender (female) | .21 | 0.41 |

| Age | 53.38 | 6.19 |

||

| Transportation | 933 | Gender (female) | .38 | 0.49 |

| Age | 56.48 | 4.41 |

||

| Construction | 168 | Gender (female) | .01 | 0.08 |

| Age | 55.22 | 2.77 |

We checked for a possible sample bias by testing for differences between those individuals dropped from the sample for any of the reasons specified above (n=279) and those which remained (n=1000). There were no significant differences along any of the variables of theoretical interest (i.e., hours worked and support measures) between those individuals dropped from the sample and those which remained.

Measures

Social support

In assessing social support, we differentiated between the degree to which individuals feel that they are able to rely on others to provide them with emotional (i.e., sympathetic and caring behaviors), and instrumental (i.e., assistance which is more tangible in nature) resources in times of need (what we refer to as the depth of available social support), and the number of others that individuals feel that they are able to turn for assistance (quantity or breadth of support) (Bacharach et al., 2007; Barrera, 1986; House. 1981; Peirce et al., 1996). These support dimensions were assessed on the basis of an instrument developed by Streeter and Franklin (1992), itself based on the classic measure developed by Caplan and associates (1975). Applying this instrument in the context of the social network approach suggested by Schonfeld and Dupree (1995), at both T1 and T2, we asked respondents to “think about those adult individuals to whom you feel the closest.” The wording of this item is nearly identical to that used in previous network studies to elicit the names of those with whom a given target has strong or intimate ties (Burt, 1984; Fischer, 1982; Verbrugge, 1977). Participants in the current study identified between 1 and 3 others as especially close to them (mean = 2.79 relations per participant). This small number of close others is consistent with other studies on close relationships in the work (e.g., Bacharach, Bamberger & Vashdi, 2005; Whright & Cho, 1992) and non-work environment (Klockner & Matthies, 2004; Fischer, 1982; Verbrugge 1977; 1983). For example, in their study of network density Fischer and Shavit (1995) found that although on average people named 11 individuals who are important to them, they considered only 3 of these people as especially close.

For each one of the close individuals named, participants were asked to select the label that best categorized the nature of each of these individuals’ relationship with the participant from a list including coworker, family member, and unrelated friend from outside of work. Overall, at Time 1 participants named 2785 close individuals. The majority of these individuals were named again at Time 2 (N=2565) with only 8% (N=220) not named again at Time 2. Out of the 2565 individuals who were named in both times, 73% were family members, 9% were coworkers and 18% were non work friends.

Breadth (Quantity) of social support from family, coworkers and non-work friends was assessed in terms of the number of others identified by the respondent from each one of the three source types. Accordingly, for both T1 and T2 we obtained three measures of breadth of support, representing the number of close others identified as family members, coworkers and non-work friends named by an individual (ranging from 0 to 3). At time 1, 14% did not name any family member, 42% named 1–2 and 44% named 3 family members. At time 2, 14% did not name any family member, 40% named 1–2, and 47% named 3 family members. Regarding coworkers, at both times 75% did not name any coworker, 23% named 1–2 and 2% named 3 coworkers. Concerning non-work friends, at Time 1, 62% of the participants did not name any close non-work friend, 33% named 1–2 and 5% named 3 friends. At Time 2, 72% did not name any friend and 28% named 1–2.

Depth (Quality) of support was measured by asking participants to assess the level of emotional and instrumental support they could rely upon receiving from each support provider named in both T1 and T2. Using the Streeter and Franklin (1992) instrument, emotional support was measured on the basis of two items asking participants to indicate the extent to which they can rely on each one of the persons named to listen, show understanding and caring, and provide advice when needed. Instrumental support was measured on the basis of two additional Streeter and Franklin (1992) items with participants asked to indicate the extent to which they can rely on each one of the persons named to go out of their way to do things (like sharing tasks and providing information) to make their life easier. Both measures of depth of social support were rated on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1: "not at all" to 4: "a great deal" (Cronbach alpha was 0.73 and 0.78).

Although instrumental and emotional support may be viewed as nested within a common latent support variable, and despite consistently high correlations between the two forms of support, researchers have tended to measure each of these support dimensions on an independent basis rather than aggregating them together into a single support measure. Among the strongest reasons for assessing instrumental and emotional support independently is the fact that they have been demonstrated to differentially relate to a range of support-relevant outcomes such as anxiety, and depression (Chi & Chou, 2001). Nevertheless, we conducted a CFA in order to assess the empirical basis for examining the impact of temporal workplace demands on two separate support dimensions as opposed to a single, overarching support variable encompassing these two dimensions. The results of this CFA analysis with regard to emotional and instrumental support indicated that a two-factor model was significantly better fitting with the data (GFI=0.99, NFI=0. 99, NNFI=0.98, RMR=0.03) than a single-factor model, in which the two support dimensions are combined (GFI=0.98, NFI=0.98, NNFI=0.96; RMR=0.13) (Δχ2 (1) = 22.08, p<0.001).

Hours worked (T1)

Participants were asked to report the amount of hours typically worked per week (on average) at their current job.

Retirement between T1 and T2

At Time 2, we assessed respondents' employment status to assign them to one of two categories, namely (a) retired (respondents who indicated that they had left their place of employment, were receiving retirement benefits, and had disengaged from the workforce, i.e., not currently working, or (b) not yet retired (respondents who either indicated that they deferred their retirement benefits and were still working for the same employer or that they retired with benefits but were employed by the same or some other employer on a part- or full-time basis). At T2, the vast majority of respondents (72%), despite their retirement eligibility, had yet to retire (i.e., 28% were fully retired).

Control variables

In testing the hypothesis noted above, we controlled for a variety of respondents’ demographic attributes including marital status, age, gender and number of children. Additionally, since health-related problems are likely to affect both the breadth and depth of support, we controlled for physical health at Time 2. Physical health was examined in terms of illness, assessed on the basis of Lifetime Histories of Physician-diagnosed Illnesses measure (11 items). This instrument, developed by the National Institute on Aging, has been used in a wide variety of epidemiological studies focusing on the health-related problems of older populations (e.g., Colsher & Wallace, 1990), and has been shown to have strong predictive validity (e.g., Salive, et al., 1992). Participants were asked to report (scale yes or no) whether they “had ever been diagnosed by a physician” with certain, chronic illnesses (e.g., high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes). Accordingly, this measure expresses the number of chronic, physician-diagnosed illnesses reported by an individual.

Analytical procedure

We applied a multi-level approach for data analysis, since all responses were nested within nine different unions, nested (in turn) within three economic sectors (i.e., manufacturing, transportation and construction). Based on this approach, we initially treated the union as a random effect and the sector as a fixed effect such that the coefficients for the independent variables at the individual level of analysis were estimated while taking into consideration the nested structure of the data. Since in all of the models the estimated variance between unions was close to zero and non-significant, we dropped the random variance component from all of the estimated models, yet controlled for the sector within which unions were nested.

Since our breadth of support is a count-based, dependent variable (expressing the number of close individuals associated with each source type) we applied a Poisson regression model to predict the number of family, coworkers and non-work friends providing support at Time 2. In order to assess whether the effect of hours worked at Time 1 on breadth of support at Time 2 is changed as a function of retirement between Time 1 and Time 2, we regressed the breadth of support from each source at Time 2 on hours worked at Time 1, retirement between Times 1 and 2, and their interaction.

We applied a within subject analysis regarding the depth of support since, for each subject, we obtained 1–3 values of emotional/instrumental support corresponding to the number of close individuals s/he named. This way, we were able to model the effect of hours worked at Time 1 on the amount of support received from each one of the close individuals named by subjects at Time 2, while taking into account the dependency between individuals who were named by the same subject. In order to assess the moderating effect of retirement and whether it differs as a function of the source of support, we ran a series of three way interactions between hours worked, retirement and the source of support. In this analysis we included only those close others who were named at both T1 and T2 (N= 2565) in order to be able to account for the depth of support at Time 1.

Restrictions on the nature of the causal influences between our variables of interest were included in these models. More specifically, Rugosa (1980) elaborated on the problems of inferring causality from a longitudinal panel data in which the relations between two variables are examined without controlling for the appropriate Time 1 variables. It has been argued that controlling for the dependant variable at Time 1 (Y1) when examining the effect of X on Y2 may not only allow one to rule out the rival hypothesis that Y causes X, but also greatly reduces the threat of spuriousness (Allison, 1990, pp. 94). Accordingly, in the current study we applied the regressor variable method, where Y2 is regressed on both Y1 and X, in order to control for the relevant support measure at Time 1 (see Alison, 1990). Since the breadth of support models were assessed by applying Poisson regression, we controlled for the natural log of the number of family members / coworkers / non-work friends at Time 1 so as to match the scale of these measures to the dependent variables.

Finally, simple slopes for the effects of hours contingent upon retirement and the source of support were evaluated on the basis of Aiken and West (1991).

Results

Means, standard deviations and correlations among the variables at the individual level (N=1000) and at the relationship level (N=2565) are displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix for variables at the individual level (N=1000) and at the social contacts level† (N=2565)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Sector (manufacturing =1) | .16 | .36 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Sector (construction =1) | .15 | .35 | −.18*** | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Gender (female=1) | .27 | .45 | −.06 | −.25*** | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Marital status (married=1) | .79 | .41 | −.00 | .08** | −.28*** | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Age | 56 | 4.71 | −.28*** | −.07* | −.27*** | .06 | |||||||||||||||

| 7. Retirement ( between T1 to T2) | .28 | .45 | −.004 | −.1*** | −.22*** | .07* | .33*** | ||||||||||||||

| 8. Hours a week work | 41.31 | 14.58 | .13*** | −.001 | −.59*** | .18*** | .25*** | .21*** | |||||||||||||

| 9. Emotional Support at T1† | 3.72 | .47 | −.02 | −.004 | .06** | −.02 | −.02 | −.04* | −.005 | ||||||||||||

| 10. Emotional Support at T2† | 3.73 | .47 | −.03 | −.00 | .04* | −.008 | −.03 | −.03† | −.05* | .53*** | |||||||||||

| 11. Instrumental Support at T1† | 3.33 | .74 | −.01 | .03 | −.04* | .09*** | .01 | .04* | .01 | .50*** | .41*** | ||||||||||

| 12. Instrumental support at T2† | 3.33 | .73 | −.02 | .02 | −.04* | .06** | −.01 | .03 | .01 | .36*** | .49*** | .59*** | |||||||||

| 13. # of family members at T1 | 1.96 | 1.09 | .06 | .03 | −.08** | .25*** | .03 | .01 | . 09** | −.007 | .02 | .03 | .02 | ||||||||

| 14. # of family members at T2 | 2.00 | 1.10 | .04 | .02 | −.07* | .22*** | .03 | −.003 | .06 | −.001 | .03 | .05** | .03 | .94*** | |||||||

| 15. # of coworkers at T1 | .34 | .66 | −.01 | −.02 | .007 | −.03 | −.03 | .02 | .05 | −.02 | −.06** | −.002 | −.02 | −.55*** | −.51*** | ||||||

| 16. # of coworkers at T2 | .36 | .69 | −.01 | −.04 | .03 | −.03 | −.02 | .03 | .04 | −.02 | −.05* | .004 | −.009 | −.52*** | −.57*** | .79*** | |||||

| 17. # of friends at T1 | .58 | .86 | −.05 | −.007 | .14*** | −.26*** | −.04 | −.03 | −.16*** | .008 | .01 | −.05** | −.01 | −.73*** | −.68*** | −.02 | .09** | ||||

| 18. # of friends at T2 | .33 | .58 | −.04 | −.01 | .10** | −.21*** | −.02 | −.02 | −.11*** | −.006 | .03 | −.07*** | −.02 | −.61*** | −.65*** | .07* | −.01 | .76*** | |||

| 19. Source (family=1) | .73 | .44 | .04* | .01 | −.07*** | .18*** | .05** | .02 | .04* | .03 | .05** | .11*** | .10*** | .76*** | .76*** | −.46*** | −.45*** | −.58*** | −.58*** | ||

| 20. Source (friends =1) | .18 | .37 | −.04* | −.01 | .10*** | −.19*** | −.04* | −.04* | −.09*** | −.004 | −.01 | −.09*** | −.09*** | −.58*** | −.58*** | .01 | −.003 | .67*** | .67*** | −.76*** | |

| 21. Physical health at T2 | 1.02 | 1.04 | −.01 | −.05† | −.06 | .02 | .10*** | .11*** | .11*** | −.04* | −.04† | −.003 | .03 | .01 | .003 | .04 | .07* | −.07* | −.05 | .02 | −.06* |

P≤0.05;

P≤0.01;

P≤0.001

Results regarding the impact of work hours and retirement on the depth of emotional and instrumental support are displayed in Table 3. Results regarding the impact of work hours and retirement on the breadth of support are presented in Table 4.

Table 3.

Hours Worked on Depth of Support Contingent upon the Source of Support and Retirement (N=2565)

| Emotional Support | Instrumental Support | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1E | Model 2E | Model 3E | Model 4E | Model 1I | Model 2I | Model 3I | Model 4I | |||||||||

| Effect | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE |

| Intercept | 2.01*** | .16 | 1.92*** | .15 | 1.91*** | .15 | 1.88*** | .15 | 1.91*** | .21 | 1.94*** | .22 | 1.94*** | ..22 | 1.93*** | .22 |

| Sector (manufacturing =1) | −.02 | .03 | −.01 | .03 | −.001 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | .04 |

| Sector (construction =1) | −.01 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | .04 | −.004 | .04 | −.003 | .04 |

| Gender (female=1) | .01 | .03 | −.03 | .03 | .03 | .03 | −.03 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | .04 |

| Marital status (married=1) | .002 | .03 | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | .02 | −.06 | .04 | −.07* | .04 | −.07* | .04 | −.07 | .04 |

| Age | −.001 | .00 | −.001 | .002 | −.001 | .002 | −.001 | .002 | −.003 | .003 | −.004 | .004 | −.004 | .004 | −.004 | .003 |

| Physical health T2 | .003 | .01 | .005 | .01 | .005 | .01 | .003 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .01 |

| Support T1 | .50*** | .01 | .50*** | .02 | .50*** | .02 | .50*** | .01 | .56*** | .01 | .56*** | .02 | .56*** | .02 | .56*** | .02 |

| Retirement (between T1 to T2) | −.01 | .02 | −.01 | .02 | .18** | .07 | .03 | .04 | .02 | .03 | .16 | .09 | ||||

| Hours (a week work) | −.002** | .001 | .004* | .002 | .01*** | .002 | −.001 | .001 | .01** | .003 | .01*** | .003 | ||||

| Source (family=1) | .05 | .03 | .06* | .03 | .07* | .03 | .02 | .04 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .05 | ||||

| Source (friends=1) | .03 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .05 | .03 | −.04 | .04 | −.05 | .04 | −.05 | .05 | ||||

| Hours*Source (family=1) | −.01*** | .002 | −.01*** | .002 | −.01*** | .002 | −.01*** | .003 | ||||||||

| Hours*Source (friends=1) | −.01** | .002 | −.01*** | .002 | −.01*** | .003 | −.02*** | .003 | ||||||||

| Retirement*Hours | −.02*** | .005 | −.02** | .007 | ||||||||||||

| Retirement*Source (family=1) | −.18** | .07 | −.13 | .09 | ||||||||||||

| Retirement*Source (friends =1) | −.21** | .08 | −.14 | .11 | ||||||||||||

| Retirement* Hours*Source (family=1) |

0.02*** | .005 | .02** | .007 | ||||||||||||

| Retirement*Hours*Source (friends =1) |

0.02*** | .005 | .02** | .008 | ||||||||||||

| −2 LL | 2029 | 2018 | 2005 | 1984 | 3838 | 3832 | 3817 | 3809 | ||||||||

| Δ −2 LL (relative to Model) | 11* (1E) | 13** (2E) | 34*** (3E) | 6 (1I) | 15*** (2I) | 23** (3I) | ||||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Family for retirees |

−.002** | .001 | −.002* | .001 | −.001 | .001 | −.01 | .001 | ||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Family for non-retirees |

−.004** | .002 | −.02 | .002 | ||||||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Coworkers for retirees |

.004* | .002 | −.01** | .004 | .01** | .003 | −.007 | .006 | ||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Coworkers non-retirees |

.007*** | .002 | .01*** | .003 | ||||||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Friends for retirees |

−.003** | .001 | .001 | .003 | −.004* | .002 | −.001 | .004 | ||||||||

| Slope of Hours on Support from Friends for non-retirees |

−.004* | .002 | −.005* | .002 | ||||||||||||

P≤0.05

P≤0.01

P≤.001

Table 4.

Hours Worked on Breadth of Support from Family, Coworkers and Friends Contingent upon Retirement

| Family Support | Co-workers Support | Friends Support | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||||||

| Effect | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE |

| Intercept | −.43*** | .16 | −.47*** | .16 | −.46*** | .16 | −0.96 | .72 | −1.81* | .82 | −2.10** | .82 | −2.11*** | .63 | −2.60*** | .66 | −2.73*** | .67 |

| Number of children | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | −.04 | .03 | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | .04 | −.01 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .03 |

| Sector (manufacturing =1) | −.01 | .03 | .002 | .03 | .002 | .03 | −.05 | .16 | .10 | .18 | .08 | .18 | .11 | .14 | .23 | .15 | ..27** | .15 |

| Sector (construction =1) | .01 | .03 | .003 | .03 | .003 | .03 | −.04 | .17 | .07 | .18 | .08 | .19 | .07 | .14 | .03 | .14 | .04 | .14 |

| Gender (female=1) | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | .13 | .13 | .30 | .16 | .40* | .17 | −.04 | .14 | −.32** | .14 | −.39** | .15 |

| Marital status (married=1) | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | −.02 | .03 | .05 | .13 | .06 | .13 | .13 | .15 | −.13 | .11 | −.15 | .10 | −.16 | .10 |

| Age | .00 | .003 | .00 | .003 | .00 | .003 | −.003 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02* | .01 | .02* | .01 |

| Physical health at T2 | −.006 | .01 | −.004 | .01 | −.004 | .01 | .06 | .05 | .06 | .05 | .06 | .05 | −.01 | .05 | .01 | .05 | .02 | .05 |

| # of Family /Coworkers/ Friends at T1 | 1.23*** | .03 | 1.23*** | .03 | 1.23*** | .03 | 1.82*** | .08 | 1.96*** | .09 | 1.99*** | .09 | 1.76*** | .08 | 1.76*** | .08 | 1.76*** | .08 |

| Retirement (between T1 to T2) | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | .03 | .01 | .13 | .08 | .14 | −.08 | .12 | −.10 | .12 | ||||||

| Hours (a week work) | −.002 | .001 | −.002 | .001 | .003 | .004 | .01* | .005 | −.02*** | .005 | −.02*** | .005 | ||||||

| Retirement * Hours | .001 | .002 | −.02* | .01 | .02* | .009 | ||||||||||||

| R-square | .18 | .19 | .19 | .38 | .38 | .47 | .33 | .35 | .36 | |||||||||

| Slope of Hours for those who retired between T1 to T2 | −.01 | .01 | .001 | .01 | ||||||||||||||

| Slope of Hours for those who did not retire between T1 to T2 | .01* | .005 | −0.02*** | .005 | ||||||||||||||

P≤0.05

P≤0.01

P≤0.001

The results with respect to Hypotheses 1 and 2 (concerning the effect of work hours on support from various sources) are presented in Models 3E of Table 3 (for the depth of emotional support), 3I of Table 3 (for the depth of instrumental support), and in Models 2 of Table 4 (for the breadth of support). The results with respect to the depth of support indicate that the source of support significantly moderate the relationship between the number of hours worked at Time 1 and the depth and emotional (b = −.01, P<.001; P<.01, for the interactions between work hours and support sources) and instrumental (b = .01, P<.001, for the interactions between work hours and support sources) support at Time 2.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the results with respect to emotional support indicate that work hours are negatively and significantly related to emotional support from family members (b = −.002, P<.01) and non-work friends (b = −.003, P<.01). Less consistent results were obtained with respect to the availability of instrumental support from family members and non-work friends and with respect to the breadth of family and non-work friends’ support. More specifically, the effects of work hours on the depth of instrumental support from family members (b = −.001, ns) and on the breadth of family support (b = −.02, ns) were not significantly different from zero. Still, consistent with Hypothesis 1, work hours were found to have negative effects on both the depth of instrumental support from non-work friends (b = −.004, P<.01) and the breadth of non-work friends’ support (b = −.02, P<.001).

Consistent with Hypothesis 2, work hours were found to be positively and significantly related with the depth of emotional (b = .04, P<.05) and instrumental (b = .01, P<.01) support from coworkers. However, the results with respect to the breadth of coworkers’ support were inconsistent with Hypothesis 2, showing an non-significant relationship between work hours and the breadth of coworkers support (b = .003, ns).

The results with respect to Hypotheses 3 and 4 (concerning the moderating effects of retirement in the relationship between work hours and support from various sources) are presented in Models 4E of Table 3 (for the depth of emotional support), Models 4I of Table 3 (for the depth and instrumental support), and in Models 3 of Table 4 (for the breadth of support). Consistent with these hypotheses, the results regarding the depth of emotional and instrumental support show significant three way interactions between hours worked at Time 1, retirement between Time 1 and Time 2, and the source of support (b = .02, P<.001; b = .02, P<.01 for emotional and instrumental support respectively). This indicates that the moderating role of support source on the relationship between work hours and the depth of support significantly varies as a function of retirement status (i.e., retired or still working).

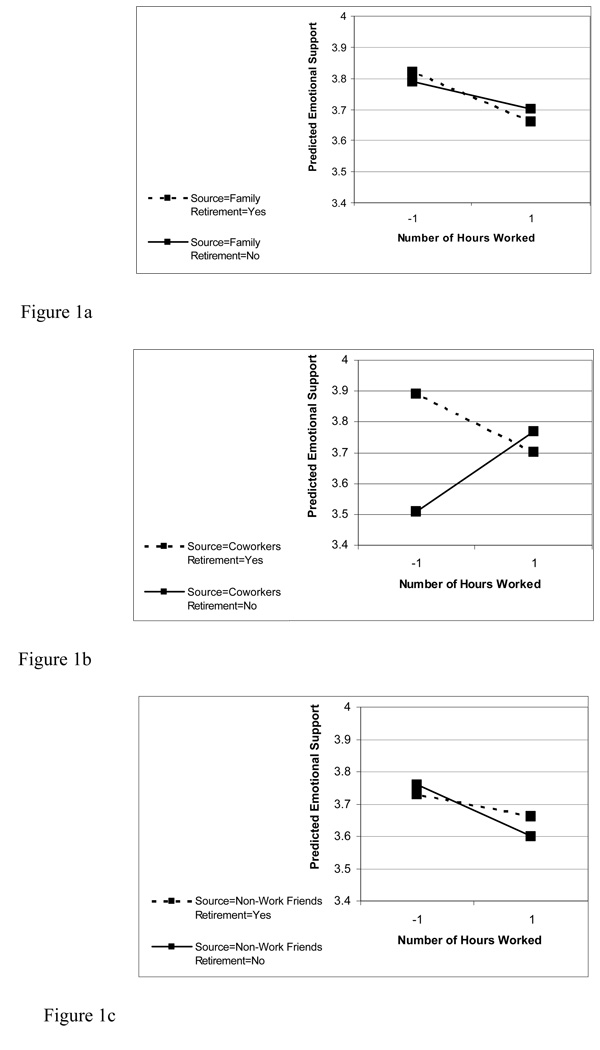

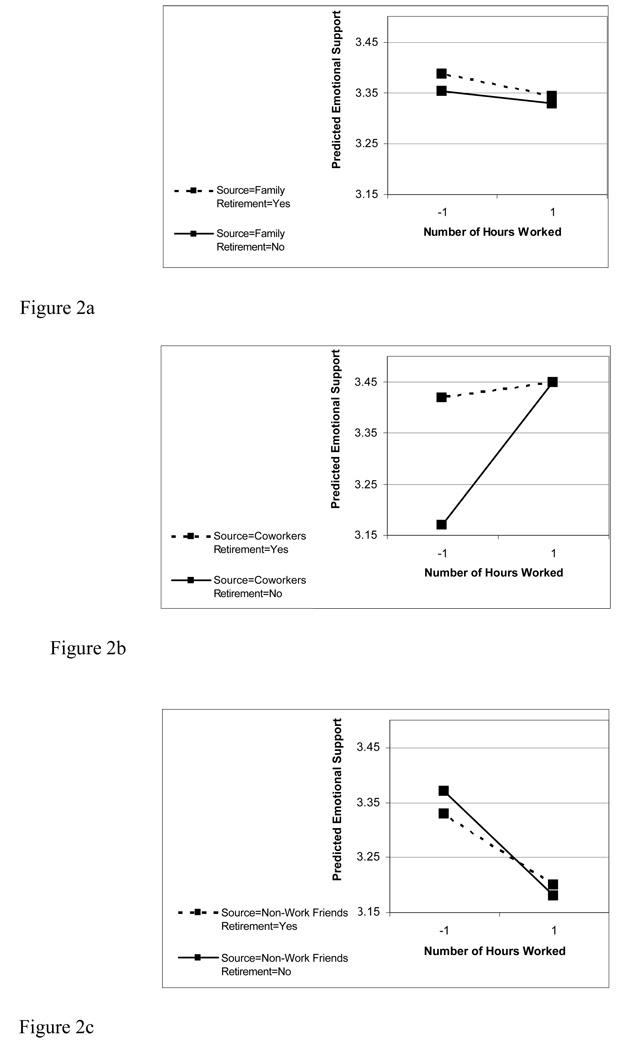

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, for those who have not yet retired, work hours were found to have a significant and positive effect (simple slope) on the depth of emotional (b =.007; P<.01) and instrumental (b =.01; P<.001) support from coworkers. This positive effect was found to be attenuated for those who retired. More specifically, we found the effect of work hours on emotional support from coworkers (Figure 1b) to be significantly negative (b = −.01, P<.01) and the effect of work hours on instrumental support from coworkers to be non-significant (b = −.007, ns) for those who retired between Time 1 and Time 2 (Figure 2b). Similar results were obtained with respect to the breadth of coworker support. The interaction between work hours and retirement was found to be negative and significant (b = −.02, P<.05) and the simple slopes analysis showed a positive and significant effect of work hours on the breadth of coworkers support for those who have not yet retired (b =.01, P<.01), and a non- significant effect of work hours on the breadth of coworkers support for those who retired (b = −.01, ns). Overall, these results indicate that any positive effect of work hours on coworkers support may be attenuated, and even reversed for those who retire.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a: Hours Worked on Emotional Support from Family Contingent upon Retirement

Figure 1b: Hours Worked on Emotional Support from Coworkers Contingent upon Retirement

Figure 1c: Hours Worked on Emotional Support from Non-Work Friends Contingent upon Retirement

Figure 2.

Figure 2a: Hours Worked on Instrumental Support from Family Contingent upon Retirement

Figure 2b: Hours Worked on Instrumental Support from Coworkers Contingent upon Retirement

Figure 2c: Hours Worked on Instrumental Support from Non-Work Friends Contingent upon Retirement

However, our results were inconsistent with Hypothesis 4. With respect to family support, the results indicated that the effect of work hours on emotional support from family members is negative and significant regardless of whether the subject has retired or not (b =−.002, P<.05 for those who retired, and b = −.004, P<.01 for those who did not retire, Δ=.002, ns). Moreover, the effect of work hours was found to be non-significant regardless of whether the subject retired, with respect to both the depth of instrumental support from family members (b = −.01; −.02, ns, for those who retired and those who did not) and the breadth of family support (b =.001, ns, for the interaction between work hours and retirement, and b =.001, ns, for the effect of work hours). Accordingly, contrary to Hypothesis 4, we conclude that regardless of work status (i.e., retired or not), the number of hours worked at Time 1 is inversely related to emotional support received from family members at Time 2 (see Figure 1a), and not significantly related to instrumental support from family members (see Figure 2a) and to the breadth of family support at Time 2.

Regarding non-work friends, inconsistent with Hypothesis 4, retirement was found to attenuate, rather than amplify the inverse relationship between hours worked at Time 1 and the availability of support at Time 2. More specifically, the slope of hours worked at Time 1 on the depth of non-work friends support at Time 2 (Figure 1c for emotional and 2c for instrumental support) was found to be negative for those who were yet to retire (b = −.004; b = −.005, P<.05 for emotional and instrumental support respectively), yet insignificant for those who retired (b =.001; b = −.001, ns for emotional and instrumental support respectively). Similar results were obtained with respect to the breadth of non-work friends support. The interaction between work hours and retirement was found to be positive and significant (b = 0.02, P<.05), and the simple slopes analysis indicate that for those who have not yet retired, hours worked at Time 1 are inversely related to the number of close non-work friends at Time 2 (b = −.02, P<.001), with this association being insignificant for those who retire between Time 1 and Time 2 (b =.001, ns).

Discussion

Taken as a whole, the results presented above suggest that temporal workplace demands on older workers are related to the quantity (breadth) of close supportive relationships with family members, coworkers and non-work friends over time, as well as to the quality (depth) of emotional and instrumental support available from each one of these sources over time. They also suggest that these associations are, in some cases, moderated by retirement.

More specifically, consistent with Hypotheses 2 and 3, and as summarized in Table 5, we found work hours at Time 1 to be associated with an increased number of close supportive relationships with coworkers, as well as with increased levels of emotional and instrumental support available from close coworkers at Time 2. However, these positive longer-term effects of work hours on coworkers' breadth and depth of support were found to be attenuated for those who retired between Time 1 and Time 2. Interestingly, in the case of emotional support, we found that the positive effect of work hours was not only attenuated for those who retired, but also reversed, such that increased hours worked prior to retirement were associated with reduced levels of emotional support available from close coworkers after the disengagement of an individual from the workplace.

Table 5.

Summary of Results of Hypothesis Testing

| Hypothesis | Source of Support | Depth | Breadth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Support |

Instrumental Support |

|||

| 1 | Non-Work Friend | Not Supported | Supported | Supported |

| 1 | Family | Supported | Supported | Not Supported |

| 2 | Co-Worker | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| 3 | Co-Worker | Supported | Supported | Supported |

| 4 | Non-Work Friend | Not Supported | Not Supported | Not Supported |

| 4 | Family | Not Supported | Not Supported | Not Supported |

In contrast, more mixed support was found for Hypothesis 1 regarding the main effect of work hours on older employees’ access to non-work-based support. Consistent with this hypothesis, work hours were inversely associated with the subsequent depth of emotional support from family and friends, instrumental support from friends, and breadth of support from friends. However, they were not associated with either the depth of instrumental support from family or the breadth of support from family.

Finally, we found no support for our prediction that retirement would intensify the inverse association between work hours and support from close family members and non-work friends (Hypothesis 4). Concerning family support, we found work hours at Time 1 to be associated with reduced emotional support from family members at Time 2 for both retirees and non-retirees. Although the inverse association between work hours and emotional support available from family members was slightly intensified for those who retired, the difference in the effect of hours between retirees and non-retirees failed to reach statistical significance. Moreover, no significant relationships were found between work hours at Time 1 and the number of close relationships with family members as well as with the depth of instrumental support available from close family members at Time 2.

Concerning non-work friends, our results consistently showed that retirement between Time 1 and Time 2 attenuates, rather than intensifies, the negative effect of work hours at Time 1 on the number of close relationships with non-work friends, as well as the level of emotional and instrumental support available from close non-work friend at Time 2. For those older workers yet to retire, work hours were negatively associated with both the breadth and depth of support from close non-work friends. However, for those who retired, the number of hours worked prior to retirement had no effect on post-retirement breadth and depth of support from close non-work friends.

Overall, these findings indicate that for older workers yet to retire, work hours are associated with increased subsequent access to support from coworkers, yet with reduced subsequent access to support from close family members and non-work friends. However, for those who do retire, the number of hours worked prior to retirement is associated with reduced subsequent access to support from both close family members and coworkers, while having no effect on their access to support from close non-work friends.

Theoretical Contribution

Our findings provide important insights into how workplace conditions and retirement may combine to contribute to the well-documented decline in the amount of support available to individuals as they age. The results indicate that working long hours is associated with increased levels of subsequent coworker support among older individuals continuing to work despite retirement eligibility. However, consistent with other models of the social consequences of retirement (Bosse et al., 1990; Bosse et al., 1993), we found retirement to attenuate the positive effect of work hours on individuals' subsequent (i.e., post-retirement) quantity of close relationships with coworkers and their access to instrumental support from coworkers. Moreover, we found retirement to completely reverse the direction of the hours-support relationship with regard to emotional support from coworkers such that for those retiring, greater pre-retirement temporal demands were associated with significantly lower levels of post-retirement coworker emotional support. It is possible that because those working longer hours perceive the workplace as their main source of affective resources (e.g., accomplishment, meaning, relaxation) (Hochschild, 1997), any geographic or emotional distancing from those providing such support (such as that often caused by retirement) is likely to take on increased saliency. This may result in a greater sense of loss and hence, an inverse association between pre-retirement hours and perceptions of the availability of emotional support from coworkers.

Our results also support the notion that working increased hours, perhaps by reducing the productivity and frequency of resource exchanges between older workers and their intimate others outside of work, limits older individuals' accessibility to support from close non-work friends. However, this effect of hours on perceived support availability was found to be attenuated, rather than intensified by retirement. This suggests that any adverse impact of temporal demands on relations with non-work friends while the individual is employed may be reversible upon retirement. In other words, it is possible that in the context of relations with non-work friends, retirement can be seen as a factor that, perhaps by reducing role-strain and overload (Moen et al., 2001), actually improves the ability of an individual to invest time and energy in non-work related friendships and hence compensate for more limited investment in this non-work domain prior to their retirement. Consistent with the theory of rational cohesion (Lawler and Yoon, 1996), retirement may facilitate increased dyadic exchanges with such non-work friends, resulting in enhanced relational commitment, and consequently, greater access to support from such individuals.

Finally, our results regarding family-based support suggest that work hours may not limit employee access to family support in terms of the quantity of close family relations and the quality of instrumental support available from family members. However, pre-retirement temporal demands were found to be associated with significantly less subsequent access to emotional support from close family members even after the disengagement of an individual from the workplace. In other words, in contrast to the apparently reparable nature of relations with non-work friends, our findings suggest that the inverse association of longer working hours with the depth of subsequent, family-based emotional support, while no more intensive for retirees relative to those still working, was still inverse among retirees. One obvious explanation for this is the distinct nature of familial relations. Unlike supportive relations with non-work friends which may be “repaired” by simply replacing non-supportive “old” friends with more support new ones, family relations are not only more difficult to replace, they may also take significantly more time (and certainly more than the 12 month interval in our study design) to repair (Ikkink & van Tilburg, 1999).

Theoretical Questions and Challenges

Aside from the insights noted above our findings raise several important questions. First, a question arises as to why work hours were found to be associated with reduced levels of emotional family support regardless of retirement, while having no effect on the breadth of support from family members and on the level of instrumental support available from family members. Concerning the breadth of support, these findings are consistent with the notion that older workers have relatively stable social relationships especially with family members. In this sense close family relations may be less subjective to termination as a function of long work hours relative to close work and non-work related friendships (see Lockenhoff & Carstensen, 2004; Forster & Stoller, 1992). Concerning instrumental support, it is possible that family members continue to provide instrumental support to those working increased hours in order to maintain the financial benefits associated with their working increased hours. In this sense, instrumental support may be a result of a mutual functional dependency between the worker and his/her close family members (Ducharme & Martin, 2000). More specifically, family members may consider the financial benefits associated with working increased hours as valuable resources and continue to provide practical assistance in response to specific needs despite the limited ability of an employee to mobilize other type of resources in the family domain.

This suggests a real difference in the nature of relations underlying emotional versus instrumental aid. The emotional exchanges of resources requires that both sides of the dyad be able to openly share their feelings and emotions, feel respected, receive reassurance when troubled, and trust the other person to be there in times of need (Wright & Aquilino, 1998). In contrast, in instrumental exchange, giving one type of aid (e.g., financial aid) may be reciprocated by the receipt of a different type of help (e.g., help with transportation or housework). Moreover, instrumental support is required only in response to particular circumstances or stressors, unlike emotional support which is routinely offered and called upon in the course of everyday interaction (Ducharme & Martin, 2000). In this sense, it is not surprising that family instrumental support was less subject to the harmful effects of work hours relative to emotional support. In short, it is only logical that that employee absence from the family domain during most of the day as well as the emotional exhaustion associated with working increased hours (Bekker, Croon & Bressers, 2005; Sluiter, van der Beek., & Frings-Dresen, 1999) primarily debilitates the ability of an employee to mobilize emotional-based resources rather than instrumental-based resources in the family domain.

Second, drawing from the notion of "loss spirals" (Hobfoll, 2002) we hypothesized that retirement intensifies the negative effect of work hours on employee access to support from family members and non-work friends. More specifically, we proposed that retirees who worked increased hours prior to retirement start their transition to retirement at a disadvantage as they experience depletion in their personal resources and also loose their primary source of support, namely their work-based relations (Bosse et al., 1990; Bosse et al., 1993). Accordingly, we associated any retirement-related stress with further depletion in retirees' personal resources, resulting in reduced ability to mobilize support-based resource in their close relationships with family members and non-work friends. However, our results indicated the opposite with regard to non-work friends, suggesting that retirement attenuates the inverse relationships between work hours and non-work friends' support. With regard to family support, our results indicated that the inverse relationship between work hours and emotional support available from family members is slightly (yet not significantly) intensified for those working increased hours. These findings suggest that retirement may affect non-work friends' relations and family relations differently. It is possible that fulfilling family obligations requires a greater investment of time and energy; involving greater normative expectations of resource investment relative to fulfilling obligations related to one's role as a close friend (Fischer, 1982; Ikkink & van Tilburg, 1999). In this sense, while retirees’ personal resources may be sufficient to reestablish or intensify old (or establish new) supportive relationships with non-work-based friends, they may be insufficient in terms of fulfilling the expectations of close family members and compensating for limited pre-retirement involvement in the family domain.

Limitations

Several limitations of our study may offer additional research opportunities. First, the moderating effect of retirement on the relationship between work hours and individuals' access to support overtime may itself be moderated by many other factors such as age, gender, marital status and physical health. For example, men and women may differ in their experience of retirement, as a result of differences in employment trajectories and gendered expectations (see Moen et al., 2001). Although a post-hoc analysis showed no significance for any possible moderating role of the factors mentioned above, we suggest that future research examine in more detail whether the moderating role of retirement differs as a function of various factors related to the individual and the workplace.

Second, while we deem it highly likely that our findings are generalizable to other work-based demands and conditions, in the current study we focused solely on the longer-term effects of work hours. In this sense, we encourage others to further explore the moderating effect of retirement on the relationships between other potential work-based demands and employee access to work and non-work related support overtime.

Third, in the current study we examined the moderating role of retirement, by examining individuals' access to support 6 months prior to their retirement eligibility (T1) and one year after the first interview (T2). As a result, those who retired were surveyed during the first several months after their retirement. This initial period is often considered to be the honeymoon phase, in which an “individual wallows in his new found freedom of time and space”, keeping him/herself busy in many leisure activities (e.g. traveling, fishing, visiting friends and family) all at the same time (Atchley, 2000: 120). However, after the honeymoon is over and life begins to slow down, many people, especially those who were highly involved in and attached to their job, often experience a period of let-down and depression (Atchley, 2000; Reitzes & Mutran, 2004). In this phase, retirees may be particularly vulnerable to any loss of work-based relations and increasingly need to rely upon family and non-work friends as an alternative basis of support. Accordingly, we suggest that future research extend the longitudinal design applied in the current study, by examining the effect of hours on retirees’ access to social support over a longer period of time as well as the implications of these effects to older individuals’ health and well-being.

Finally, the sample used in the current study may have introduced bias into our results in several ways. First, in the current study we focused on retirement-eligible workers, defined in terms of meeting union's criteria for early or full retirement benefits. Because these criteria vary from union to union, some retirement-eligible members in the sample are relatively young (average age was 56), and hence our sample may not be representative of an older population of retirees. Still, the results of the current study (i.e., decreased access to support from family members and former co-workers) are expected to be stronger for older retirees given their increased health vulnerabilities. Accordingly, testing our hypotheses based on a relatively younger sample of retirees is somewhat conservative. Second, the sample in this study was largely obtained from the transportation sector. Since this sector includes flight attendants who may work unusual and extended hours, the effect of work hours on coworkers support may result from stronger emotional dependencies between coworkers characterizing this sector. Still, since we assessed our models while controlling for sector differences, and since we found no significant variation in support received between unions, any bias resulting from sector-based or union-based differences is likely to be very small. Third, possible differences between retirees who plan to gain new employment and those who do not may have compromised the validity of this study. We encourage others to extend the current study, examining whether future employment intentions moderate the effect of work hours on retirees’ supportive relations.

Practical implications

Despite these limitations our findings may shed new light as to the link between work hours and older individuals' health and well-being. With regard to older individuals who have not retired, the results of the current study indicate that although work hours increase these individuals’ access to social support from coworkers, they nevertheless reduce their subsequent access to support from both their close family members and non-work friends. While such an increase in the availability of coworkers’ support may be valuable to both the workers and the organization, non-work related support may, in many cases, play a more important role in maintaining employee health and well-being. For example, although it has been suggested that relative to coworkers, family members are a less effective source of social support because their absence from the workplace reduces their ability to immediately render social support to stressed employees (Fenlason & Beehr, 1994), researchers also acknowledge that many job stressors may be generated by coworkers themselves (e.g. work overload, role conflict). Such circumstances, where the stressor is generated by the same source from which social support is received, may lead to cognitive dissonance, resulting in discomfort or tension, adding to the person's strain (Beehr et al., 2003). Thus, in order for social support to be effective in alleviating job stress, the sources of support may need to be independent of the sources of stress (Beehr et al., 2003). Accordingly, studies indicate that having non-work related support may help workers recover from stressful work days and better handle the pressure associated with their work and, consequently perform better and experience improved health and well-being (see Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). This implies that the reduction in family and non-work friends support as a function of increased working hours may debilitate the ability of employees to cope with various stressful conditions at work, especially those generated by their coworkers on the job.

Additionally, for those older individuals who do retire, working longer hours prior to retirement was found to be associated with reduced access to support from both their close coworkers and close family members. This is notable in that researchers have stressed the importance of supportive relations in promoting the health and well-being of retirees. More specifically, they (Atkinson, Liem & Liem, 1986; Fischer, 1982; Kim & Moen, 2002) note that as older workers retire, their work-related relationships tend to weaken dramatically and they are likely to increase their reliance on family members and non-work friends as their central sources of social support. Additionally, when experiencing chronic stressors such as major illnesses or loss of family member, family support is likely to play a critical role in employee coping capability since family members are more likely to be responsive to a crisis experienced within the family (Eggebeen & Davey, 1998). Accordingly, a work schedule that debilitates employee's access to family support even after the disengagement of an employee from the workplace, may have long-term negative implications with respect to the ability of older individuals to successfully adjust to retirement and cope with the stresses of aging.

In summary, precisely because the reduction in older individuals’ access to support from family members and non-work friends prior to retirement and the reduction in their access to family and coworkers support after retirement may have a significant negative impact on the longer-term health and well-being of these individuals (Hedge et al., 2006; Kim & Moen, 2002), it is important to recognize the effects of temporal workplace demands on support availability and how retirement may moderate such effects. For managers, labor leaders and policy makers, our findings indicate that while some older workers may be interested in working longer as a means by which to enhance their financial security in retirement, it is nevertheless important to keep in mind the link between such temporal demands and older employees' subsequent access to social support. Moreover, given the recognized impact of social support on the health and emotional well-being of older adults, it may be important for such decision makers to consider ways to structure work schedules such that these workers may be able to maintain or even increase their ability to mobilize social resources in both work and non-work domains. By adopting such schedules, they are likely to enhance older workers’ ability to cope not only with workplace demands, but also with the stressors associated with actual or impending retirement (Kim & Moen, 2002; Nuttman-Shwartz, 2004).

To the extent that employers and/or older workers may be reluctant to adjust work schedules, consideration should be given as to how employers, unions and government may be able to fill the support “gap” potentially generated by such work practices. For example, employers might be encouraged to expand employee assistance services to their retirees, while unions might consider expanding retiree clubs to incorporate more formal mechanisms of peer support (Bacharach, Bamberger, Sonnenstuhl & Vashdi, 2007).

Biographies

Inbal Nahum-Shani

Inbal Nahum-Shani received her PhD in Behavioral Sciences and Management in 2009, from the Technion - Israel Institute of Technology. She is a research associate at the Methodology Center, The Pennsylvania State University. Current research interests include peer relations and helping processes in the workplace, research methods and experimental designs for behavioral sciences and organizational research.

Peter Bamberger

Peter A. Bamberger is Professor of Organizational Behavior at the Recanati Graduate School of Management, Tel Aviv University, Senior Research Scholar at the School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell University, and an Associate Editor of the Academy of Management Journal. Current research interests include peer relations and helping processes in the workplace, and employee emotional wellbeing. Co-author of Human Resource trategy (with Ilan Meshulam Sage, 2000) and Mutual Aid and Union Renewal (with Samuel Bacharach and William Sonnenstuhl, Cornell Univ. Press, 2001), Bamberger has published over 60 referred journal articles in such journals as Administrative Science Quarterly, Academy of Management Journal, Academy of Management Review and Journal of Applied Psychology. He received his Ph.D. in organizational behavior from Cornell University in 1990.

Contributor Information

Inbal Nahum-Shani, Technion - Industrial Engineering & Management, Haifa, Israel.

Peter A. Bamberger, Technion: Israel Institute of Technology - Industrial Engineering & Management Technion City, Haifa 32000, Israel peterb@tx.technion.ac.il

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alpass FM, Neville S. Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging and Mental Health. 2003;7:212–216. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Fuhrer R, Jackson JS. Social support and reciprocity: A cross-ethic and cross national perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1990;7:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Atchley R. Retirement as a social role. In: Gubrium JF, Holstein JA, editors. Aging and Everyday Life. Blackwell; 2000. pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson T, Liem R, Liem JH. The social costs of unemployment: implications for social support. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1986;27:317–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger P, Cohen A, Doveh E. Retirement, social support and drinking behavior: A cohort analysis of males with a baseline history of problem drinking. Journal of Drug Issues. 2007;37:717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Vashdi D. Diversity and homophily at work: Supportive relations among white and African-American peers. Academy of Management Journal. 2005;48:619–644. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ, Vashdi D. Aging and drinking problems among mature adults: The moderating effects of positive alcohol expectancies and workforce disengagement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;69:151–159. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Parry J. Renegotiating identity and relationships: Men and women’s adjustments to retirement. Aging and Society. 24:213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera MJR. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American journal of community psychology. 1986;14:413–445. [Google Scholar]

- Becker PE, Moen P. Scaling back: Dual-earner couples’ work-family strategies. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:995–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr TA, Farmer SJ, Glazer S, Gudanowski DM, Nair VN. The enigma of social support and occupational stress: Source congruence and gender role effects. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2003;8:220–231. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.8.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekker MHJ, Croon MA, Bressers B. Childcare involvement, job characteristics, gender and work attitudes as predictors of emotional exhaustion and sickness absence. Work & Stress. 1999;19:221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR, Spiro A, Mroczek DK. Change in social support after retirement: Longitudinal findings from the normative aging study. Journal of Geronthology: Psychological Sciences. 1993;48:P210–P217. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.p210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosse R, Aldwin CM, Levenson MR, Workman-Daniels K, Ekerdt DJ. Differences in social support among retirees and workers: Findings from the normative aging study. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:41–47. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt RS. Network items and the General Social Survey. Social Networks. 1984;6:293–339. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan RD, Cobb S, French JRP, Van Harrison R, Pinneau SR. Job Demands and Workers Health: Main Effects and Occupational Differences. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Chambel MJ, Curral L. Stress in academic life: Work characteristics as predictors of student well-being and performance. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2005;54:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Chi I, Chou KL. Social support and depression among elderly Chinese people in Hong Kong. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2001;52:231–252. doi: 10.2190/V5K8-CNMG-G2UP-37QV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colsher PL, Wallace RB. Elderly men with histories of heavy drinking: Correlates and consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1990;51:528–535. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Bulters AJ. The loss spiral of work pressure, work–home interference and exhaustion: Reciprocal relations in a three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2004;64:131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E, Geurts SAE, Bakker AB, Euwema M. The impact of shiftwork on work-home conflict, job attitudes and health. Ergonomics. 2004;47:987–1002. doi: 10.1080/00140130410001670408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devoe SE, Pfeffer J. Hourly payment and volunteering: The effect of organizational practices on decisions about time use. Academy of Management Journal. 2007;50:783–798. [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Martin JK. Unrewarding Work, Coworker Support, and Job Satisfaction. Work and Occupations. 2000;27:223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ, Davey A. Do safety nets work? The role of anticipated help in times of need. Journal of marriage and the family. 1998;60:939–950. [Google Scholar]

- Fenlason KJ, Beehr TA. Social support and occupational stress: Effects of talking to others. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 1994;15:157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Fielden SL, Pecker CJ. Work stress and hospital doctors: A comparative study. Stress Medicine. 1999;15:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CS. To Dwell Among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer FM, Moreno CRdeC, Fernandez RdeL, Berwerth A, Coffani dos Santos AM, Bruni AdeC. Day-and shiftworkers' leisure time. Ergonomics. 1993;36:43–49. doi: 10.1080/00140139308967853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Shavit Y. National differences in network density: Israel and the United States. Social Networks. 1995;17:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-brown J, Muntaner C, Lipscomb J, Trinkoff A. Demanding work schedules and mental health in nursing assistants working in nursing homes. Work & Stress. 2004;18:292–304. [Google Scholar]