Abstract

Three periplasmic N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases are critical for hydrolysis of septal peptidoglycan, which enables cell separation. The amidases cleave the amide bond between the lactyl group of muramic acid and the amino group of L-alanine to release a peptide moiety. Cell division amidases remain largely uncharacterized because suitable substrates to study them have not been available. Here, we use synthetic peptidoglycan fragments of defined composition to characterize the catalytic activity and substrate specificity of the important E. coli cell division amidase, AmiA. We show that AmiA is a zinc metalloprotease that requires at least a tetrasaccharide glycopeptide substrate for cleavage. The approach outlined here can be applied to many other cell wall hydrolases and should enable more detailed studies of accessory proteins proposed to regulate amidase activity in cells.

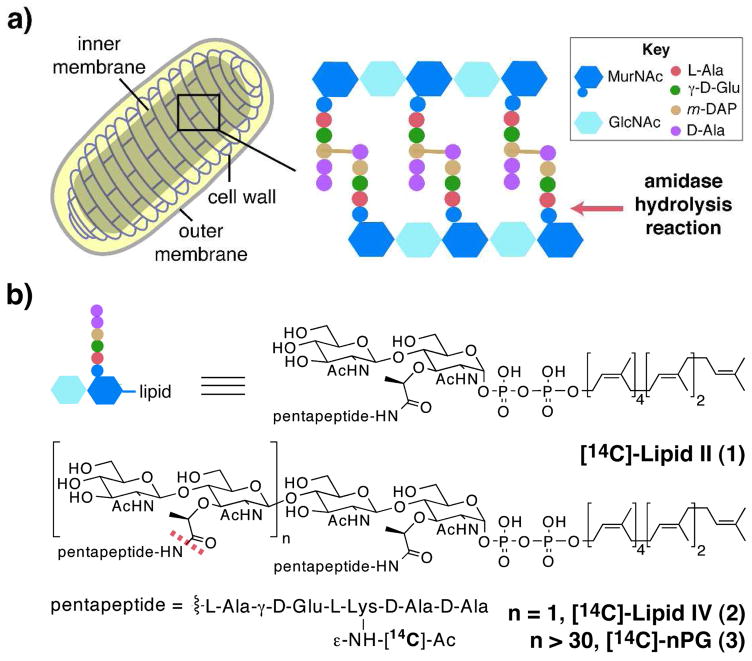

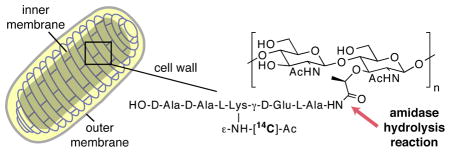

The bacterial cell wall (murein sacculus) is an essential cellular component that maintains cell shape and protects against lysis due to high internal pressure. It is composed of crosslinked strands of peptidoglycan (PG) that form a mesh-like structure around the inner membrane (Figure 1a).1 Although it provides stability, the cell wall is a dynamic structure; it is continuously modified by a number of synthetic and degradative enzymes that are finely tuned to allow the sacculus to grow and divide without lysing. The action of degradative enzymes known as murein hydrolases is especially critical during the late stages of cell division. In Escherichia coli, three periplasmic N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidases, AmiA, AmiB, and AmiC, have been shown to be particularly important for hydrolysis of septal PG, which enables cell separation.2 The amidases cleave the amide bond between the lactyl group of muramic acid and the amino group of L-alanine to release a peptide moiety (Figure 1b). Cell division amidases remain largely uncharacterized because suitable substrates to study them have not been available.3 Existing assays to monitor amidase activity are mainly based on in-gel degradation of isolated murein sacculi, which are heterogeneous, insoluble, and contain peptide chains of varying length, composition, and degree of crosslinking.1 This variability complicates any attempts to analyze amidase substrate preferences and possible modes of activation.

Figure 1.

E. coli amidases cleave peptide crosslinks from peptidoglycan (PG): (a) schematic representation of an E. coli cell. Amidase activity is required for cell separation to occur during division; (b) chemical structures of synthetic labeled PG fragments Lipid II (1), Lipid IV (2) and uncrosslinked (nascent) PG (3).1c

We have developed methods to synthesize the PG precursors Lipid II (1)4a–b and Lipid IV (2)4c, and have established enzymatic methods to convert these substrates to longer glycan strands (nPG, 3) that vary only in chain length.4c–e Here, we use these defined PG substrates to characterize the E. coli cell division amidase, AmiA.5 The approach described, which is applicable to many other amidases and cell wall hydrolases, enables a more detailed understanding of the activity and regulation of this important class of enzymes.

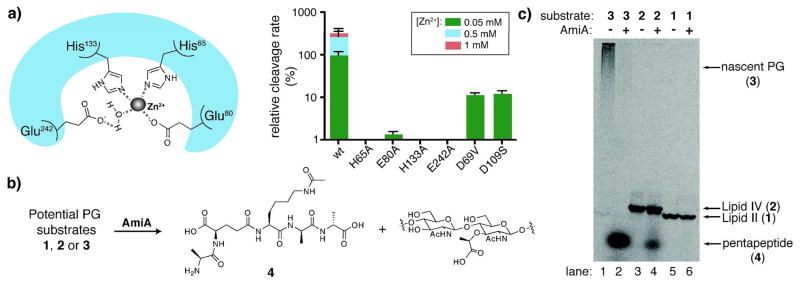

AmiA is a member of the zinc-dependent amidase 3 family, and one member, B. polymyxa va. colistinus CwlV, has been crystallized (PDB ID 1JWQ), allowing us to predict the active site residues involved in metal binding (Figure 2a).6 We overexpressed and purified C-terminally His-tagged AmiA7 and incubated it with nPG containing a radiolabel on the pentapeptide (3) in the presence and absence of zinc. Reactions were analyzed using paper chromatography.8 Unreacted nPG remains at the baseline, cleaved peptides migrate, and conversion is quantified by scintillation counting. The peptide product was verified using an authentic standard. Control experiments using lysozyme confirmed that nPG (3) could be cleaved by a PG hydrolase and that the reaction could be analyzed by paper chromatography (Figure S1). Without added zinc, AmiA exhibited no initial activity; in the presence of Zn2+, the radiolabeled peptide was cleaved from nPG (3) in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2a, right, wt rates). Adding zinc chelators such as EDTA and 1,10-phenanthroline prevented hydrolysis, but the reaction could be rescued by supplying an excess of zinc (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of AmiA substrate preferences and catalytic features: (a) predicted zinc-binding site of AmiA based on alignment with B. polymyxa var. colistinus CwlV (left); comparison of relative cleavage rates of 3 (7.2 μM) by mutants of AmiA (4.0 μM) (right); (b) reaction scheme for AmiA cleavage of [14C]-pentapeptide (4) from potential PG substrates that differ in length; (c) gel electrophoresis of 3 (lanes 1, 2), 2 (lanes 3, 4), and 1 (lanes 5, 6) without and with AmiA addition, respectively, under similar reaction conditions. AmiA cleaves 3 and 2, but not 1, to produce a new band that represents 4.

We also examined the initial rates of several mutants made based on comparisons of amidase family 3 catalytic domains. E242 is predicted to act as a general base catalyst, and H65, E80 and H133 are proposed to coordinate zinc to form the active site (Figure 2a). Mutation of any of these residues results in a full loss of activity, except for E80A, which suffered a 100-fold decrease in rate compared to wt (Figure S3). Altering residues D69 and D109, which are also highly conserved but are not predicted to be essential for activity, produced more modest decreases in reaction rate (about 10-fold less than wt). We have concluded that AmiA is a zinc-dependent metalloprotease with an active site configuration similar to CwlV.

The substrate requirements of CwlV, AmiA, or related autolytic amidases have not been determined: until now, the murein sacculus was the only reported substrate for these enzymes. In order to assess the substrate requirements of AmiA, we tested defined PG fragments of different glycan chain lengths that represent various stages of PG synthesis in the periplasm (Figure 2b). The substrates were incubated with purified enzyme under similar conditions and the reactions were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Figure 2c).9 AmiA cleaves substrates 2 and 3 to produce a common low molecular weight band, which was identified as the released pentapeptide (4) by correlation to an authentic standard using HPLC and electrophoretic mobility (Figure S4). AmiA does not cleave the peptide from 1 (compare lanes 2 and 4 to lane 6), and a maximum of 50% of the radiolabeled peptide can be cleaved from 2 (data not shown). These results show that Lipid II (1) is not a substrate and suggest that AmiA contains an extended binding pocket that recognizes sugars on either side of the glycopeptide substrate. Consistent with this idea, disaccharide-peptide fragments obtained by treating nPG (3) with lytic transglycosylases are also not cleaved by AmiA (Figure S5). Hence, our results show that AmiA requires at least a tetrasaccharide as a substrate.

The use of compositionally well-defined PG polymer substrates has allowed us to characterize a cell wall amidase, E. coli AmiA, involved in PG degradation during division. The turnover number for cleavage of the polymer is 0.05 min−1 (Figure S3). Since cleavage rates from sacculi by similar purified enzymes have not been reported, there is no in vitro data for comparison.3d Although this rate is slower than estimates required to support bacterial growth,10 slow rates are typically observed in vitro for the enzymes that synthesize glycan strands.11 A possible explanation is that cell wall synthetic and degradative enzymes are proposed to operate as components of multi-protein machines with tightly-coordinated activities. Faster in vitro rates may be observed when other important components of the system are reconstituted. Some protein candidates for amidase regulation have been suggested, but it is unclear if they simply recruit amidases to the appropriate cellular location or if they influence activity through direct interaction with the amidase or its substrate.1,12 Access to homogeneous substrates rather than crude cell wall fractions provides the capability to evaluate amidase kinetics in response to prospective activators and could, in turn, help illuminate the nature of these complex interactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM066174).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures including synthesis of peptide standard, cloning and purification of proteins, rate and gel electrophoresis analysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Holtje JV. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:181–203. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.1.181-203.1998.Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier P, Foster S. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:259–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00099.x.(c) Peptide side chains in synthetic PG fragments were simplified to L-Lys in place of m-DAP (see 4e).

- 2.Heidrich C, Templin MF, Ursinus A, Merdanovic M, Berger J, Schwarz H, de Pedro MA, Holtje JV. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41:167–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MurNAc-peptides have been used to characterize PG recycling amidases but are not substrates for division amidases. Recycling amidase assays: Van Heijenoort Y, Van Heijenoort J. FEBS Lett. 1971;15:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80041-8.Lee M, Zhang W, Hesek D, Noll BC, Boggess B, Mobashery S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8742–8743. doi: 10.1021/ja9025566.Assays using sacculi: Ghuysen JM, Tipper DJ, Strominger JL. Methods Enzymol. 1966;8:685–699.Margot P, Roten CA, Karamata D. Anal Biochem. 1991;198:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90499-j.Broad substrate scope: Uehara T, Park JT. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:5634–5641. doi: 10.1128/JB.00446-07.

- 4.(a) Men H, Park P, Ge M, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2484–2485. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ye XY, Lo MC, Brunner L, Walker D, Kahne D, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3155–3156. doi: 10.1021/ja010028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang Y, Fechter EJ, Wang TS, Barrett D, Walker S, Kahne DE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3080–3081. doi: 10.1021/ja069060g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Perlstein DL, Zhang Y, Wang TS, Kahne DE, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12674–12675. doi: 10.1021/ja075965y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang TS, Manning SA, Walker S, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14068–14069. doi: 10.1021/ja806016y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung HS, Yao Z, Goehring NW, Beckwith J, Kahne D. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911674106. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shida T, Hattori H, Ise F, Sekiguchi J. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28140–28146. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103903200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Supporting Information (Figure S3).

- 8.(a) Anderson JS, Matsuhashi M, Haskin MA, Strominger JL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;53:881–889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.53.4.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen L, Walker D, Sun B, Hu Y, Walker S, Kahne D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5658–5663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931492100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrett D, Wang TS, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Kahne D, Walker S. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31964–31971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705440200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reported rates for peptidases that cleave non-polymeric PG are faster (also see 3b): Hesek D, Suvorov M, Morio K, Lee M, Brown S, Vakulenko SB, Mobashery S. J Org Chem. 2004;69:778–784. doi: 10.1021/jo035397e.Firczuk M, Bochtler M. Biochemistry. 2007;46:120–128. doi: 10.1021/bi0613776.

- 11.Sauvage E, Kerff F, Terrak M, Ayala JA, Charlier P. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32:234–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1171–1182. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Uehara T, Dinh T, Bernhardt TG. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5094–5107. doi: 10.1128/JB.00505-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.