Less than 50% of patients with heart failure in community practice receive an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and then only usually at the instigation of or when prescribed by a hospital doctor.1–3 Fear of side effects seems to be a barrier to starting treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors,3,4 reflecting the lack of substantial studies to show the safety of giving them in primary care.

Methods and results

General practitioners in 47 practices in the United Kingdom recruited patients with mild to moderate heart failure who had been receiving chronic diuretic treatment. Exclusion criteria were age >80 years, frusemide dose >100 mg/day, systolic arterial pressure <100 mm Hg, serum creatinine concentration >250 μmol/l, and sodium concentration <135 mmol/l.

Plasma concentrations of N-terminal atrial natriuretic peptide were measured from blood samples taken before randomisation at a core laboratory.5 Plasma concentrations >2.8 ng/ml indicated important cardiac dysfunction.6

Patients were randomised, double blind, to receive quinapril 5 mg or placebo. Blood pressure was monitored for 3 hours. Quinapril or matching placebo was subsequently titrated over 3 days to 20 mg/day. After 1 week patients were reassessed and then, without breaking blinded-treatment, all received 5 mg of quinapril. Patients were again monitored, titrated to 20 mg of open label quinapril, and reviewed after a further week.

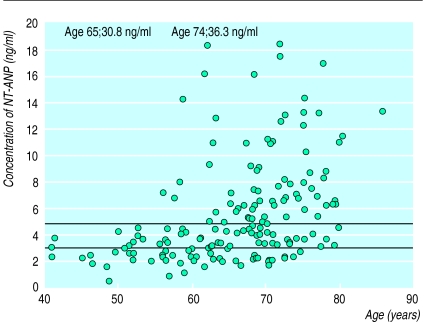

The original intention was to recruit 1000 patients giving a 95% probability of observing any adverse event with a frequency >0.34%. The power of the study was reduced because only 178 patients were randomised, 96 of whom received placebo initially. The study was terminated because of slow recruitment. Plasma concentrations of NT-ANP are shown in the figure.

No serious adverse events occurred within 24 hours of starting quinapril. Blood pressure fell to a nadir of 133/78 mm Hg in patients receiving quinapril and 138/82 mm Hg in those receiving placebo at 2 hours post dose. Eleven patients (13.4%) randomised to receive quinapril and 5 (5.2%) receiving placebo had an asymptomatic fall in systolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg or to <90 mm Hg (all predefined). After one week serum creatinine concentration did not differ from baseline (112 μmol/l (interquartile range 98-122 μmol/l) with quinapril and 110 μmol/l (92-120 μmol/l) with placebo).

Comment

This is the first placebo controlled clinical trial reporting the safety of starting angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in primary care for selected patients with heart failure. Although the study was stopped prematurely because of slow recruitment (which may reflect continuing safety concerns), a frequency of serious adverse events of >2% (one in 50 initiations) was excluded. Furthermore, monitoring blood pressure after the first dose of quinapril seems unnecessary in appropriately selected patients.

The certainty of the diagnosis of heart failure in this study is of concern but the aim was to reflect the usual clinical setting. Access to echocardiography is limited and only the minority of patients undergo echocardiography.2 Although diuretics that lower plasma concentrations of atrial natriuretic peptide were used,6 76% of patients had concentrations of N-terminal atrial natriuretic peptide that seem diagnostic of important ventricular dysfunction in epidemiological studies.7 This implies that general practitioners identified patients with cardiac dysfunction reasonably accurately in this study, although precise identification of the cause of dysfunction still requires echocardiography.

Figure.

N-terminal atrial natriuretic peptide (NT-ANP) versus age in study population. Lower line (2.8 ng/ml) indicates optimal value for distinguishing between patients with and without major left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction ⩽30%) in a population survey6; upper line (4.8 ng/ml) is median in study. Assays in this study and from the population survey were performed in the same laboratory

Footnotes

Funding: All drugs for the study were supplied by Warner-Lambert Pharmaceuticals.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Mair FS, Crowley TS, Bundred PE. Prevalence, aetiology and management of heart failure in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:77–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke KW, Gray D, Hampton JR. Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure. Br Heart J. 1994;71:584–587. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.6.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Houghton AR, Cowley AJ. Why are angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors underutilised in the treatment of heart failure by general practiotioners. Int J Cardiol. 1997;59:7–10. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)02904-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleland JGF. ACE inhibitors for the prevention and treatment of heart failure: why are they ‘under-used’? J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9:435–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleland JGF, Ward S, Dutka D, Habib F, Impallomeni M, Morton IJ. Stability of plasma concentrations of N and C terminal atrial natriuretic peptides at room temperature. Heart. 1996;75:410–413. doi: 10.1136/hrt.75.4.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JV, Woodruff PWRB, Bloom SR. The effect of treatment of congestive heart failure on plasma atrial natriuretic peptide concentration: longitudinal study. Br Heart J. 1987;57:578–579. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonagh TA, Robb SD, Morrison CE, Morton JJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, McMurray JJ, et al. Natriuretic peptides as screening tools for left ventricular dysfunction [abstract] Eur Heart J. 1996;17(suppl):317. [Google Scholar]