Abstract

Predictions about the ecological consequences of oceanic uptake of CO2 have been preoccupied with the effects of ocean acidification on calcifying organisms, particularly those critical to the formation of habitats (e.g. coral reefs) or their maintenance (e.g. grazing echinoderms). This focus overlooks the direct effects of CO2 on non-calcareous taxa, particularly those that play critical roles in ecosystem shifts. We used two experiments to investigate whether increased CO2 could exacerbate kelp loss by facilitating non-calcareous algae that, we hypothesized, (i) inhibit the recovery of kelp forests on an urbanized coast, and (ii) form more extensive covers and greater biomass under moderate future CO2 and associated temperature increases. Our experimental removal of turfs from a phase-shifted system (i.e. kelp- to turf-dominated) revealed that the number of kelp recruits increased, thereby indicating that turfs can inhibit kelp recruitment. Future CO2 and temperature interacted synergistically to have a positive effect on the abundance of algal turfs, whereby they had twice the biomass and occupied over four times more available space than under current conditions. We suggest that the current preoccupation with the negative effects of ocean acidification on marine calcifiers overlooks potentially profound effects of increasing CO2 and temperature on non-calcifying organisms.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, climate change, habitat resilience, phase shift, turf-forming algae

1. Introduction

A vexing challenge to ecological research is to identify the perturbations that cause systems to undergo shifts from one state to another (Scheffer et al. 2001). Shifts in systems often occur quite suddenly because their drivers can be insidious and combine to alter interactions or competitive relationships between key species (Suding & Hobbs 2009). Factors that subtly undermine the resilience of systems are generally unrecognized (Scheffer et al. 2001), and we have an incomplete understanding of the effects of long-term perturbations (e.g. marine eutrophication and switches in algal dominance; Smith & Schindler 2009). Nonetheless, ecosystems continue to change, and the need to understand how future conditions (e.g. climate) may contribute to this change has become a fundamental area of ecological research.

The role of global environmental change in driving habitat shifts in marine ecosystems has received heightened attention (e.g. Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007; Hughes et al. 2007). Marine waters currently absorb approximately 30 per cent of the anthropogenically derived CO2 from Earth's atmosphere, and the resulting ocean acidification has been predicted to have drastic effects over the next 100 years (Feely et al. 2004; Orr et al. 2005). Unsurprisingly, research on the effects of climate change has a disproportionate focus on the effects of ocean acidification on calcareous organisms that form habitats (i.e. coral reefs; Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2007; Anthony et al. 2008; Kuffner et al. 2008) or maintain habitats (e.g. grazers; Fabry et al. 2008; Byrne et al. 2009). However, research into the role of the changing climate in the loss of marine habitats has been largely restricted to tropical waters (i.e. coral reefs), while in temperate systems the focus has been centred on individual organisms (e.g. Dupont et al. 2008; Parker et al. 2009). This focus has, to date, overlooked historical and continuing deforestation of algal canopies across the world's temperate coastline (Eriksson et al. 2002; Airoldi & Beck 2007; Connell et al. 2008).

Kelp forests occur along the majority of the world's temperate coastlines, and are among the most phyletically diverse and productive systems in the ocean (Mann 1973). On many coasts where humans have altered chemical and biological conditions, however, canopies of algae (e.g. kelp forests) have been replaced by mats of turf-forming algae (Eriksson et al. 2002; Airoldi & Beck 2007; Connell et al. 2008). While kelp canopies inhibit turfs (Irving & Connell 2006; Russell 2007), developing theory explains shifts from canopy to turf domination as a function of reduced water quality that enables the cover of turf to expand spatially and persist beyond its seasonal limits (Gorman et al. 2009), subsequently inhibiting the recruitment of kelp and regeneration of kelp forests. Unlike kelps, many turf-forming species are ephemeral and require increased resource availability to enable their physiology and life history to be competitively superior to perennial species (Airoldi et al. 2008). It is critical, therefore, to identify future conditions that would have positive effects on turfs, thereby exacerbating the loss of algal canopies.

Although recent studies have identified the effects of anticipated levels of acidification on calcareous temperate algae (e.g. Martin & Gattuso 2009; Russell et al. 2009), none has examined the effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on non-calcareous species such as algal turfs. Therefore, the purpose of our study was twofold: (i) to determine: (i) whether turfs do in fact inhibit the recruitment of kelp under human-mediated conditions (i.e. on a metropolitan coast), and, if so, (ii) to determine whether future conditions could exacerbate the currently observed shift from kelp to turf-dominated reefs. We tested the hypotheses that (i) the removal of turfs on a metropolitan coast would cause greater recruitment of kelp and (ii) the abundance of turfs would increase under combined future conditions (i.e. elevated CO2 and temperature).

2. Material and methods

(a). Ability of turfs to inhibit kelp recruitment

We first tested the prediction that the removal of algal turfs from turf-dominated ecosystems (i.e. degraded systems; Connell et al. 2008) would enable recruitment of kelp (Ecklonia radiata) to increase. Algal turf and associated sediment were removed from 12 replicate 1 m2 plots to expose the underlying substrate. These plots and 12 replicate controls (1 m2 untouched plots) were positioned within 5 m of remnant patches of canopy, which acted as a source of recruits. This procedure was repeated at three sites (separated by greater than 1 km) that were associated with both extensive covers of turfs and remnant patches of canopy on the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia. The number of kelp recruits in plots was quantified in April 2008, approximately 12 months after turfs were removed.

(b). Effect of future conditions on turfs

Algal turfs were exposed to current and predicted future concentrations of CO2 (380 and 550 ppm, respectively) in crossed combination with ambient and elevated temperatures (17°C and 20°C, respectively) in a mesocosm experiment over 14 weeks from March–June 2008. Both future CO2 and temperatures were based on IS92a model predictions for the year 2050 (Meehl et al. 2007), with the ambient temperature being the summer maxima at the algal collection site. There were two replicate mesocosms per combination of treatments (n = 5 replicate turf specimens per mesocosm).

The response of turfs to experimental conditions was assessed using three response variables: percentage cover and dry mass of algae recruiting to initially unoccupied substrate (5 × 5 cm fibreboard tiles), and effective quantum yield of algae on the original rock substrate. The percentage cover of algae was visually estimated to the nearest 5 per cent at the end of the experiment (n = 5 tiles per mesocosm) as suggested by Drummond & Connell (2005). Dry mass of algae was measured by carefully scraping all algae from a standard area on each tile (6.25 cm2) into a pre-weighed aluminium tray, which was then rinsed with fresh water to remove excess salt and dried at 60°C for 48 h. Fibreboard tiles were used as unoccupied substrate to remove confounding by any differences in either percentage cover or mass of algal samples that were placed into the experiments. Further, the tiles were placed into mesocosms with the rough side uppermost, as turfs readily recruit to this surface (Irving & Connell 2002), which has similar roughness to basalt rock at the collection site.

Chlorophyll fluorescence, a relative measure of the photochemistry of Photosystem II (Genty et al. 1989), was measured under experimental light conditions using a pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometer (Walz, Germany). Effective quantum yield (Y) was calculated using the equation Y = (F′m−F)/F′m (Genty et al. 1989), where F′m is the maximal fluorescence and F the minimal fluorescence under illuminated conditions (van Kooten & Snel 1990). F was measured by holding the fibre optics of the PAM fluorometer in contact with the algal sample (in situ in mesocosms) and exposing it to a pulsed measuring beam of weak red light (0.15 µmol m−2 s−1, 650 nm), followed immediately by a pulse of saturating actinic light (0.8 s, 6000 µmol m−2 s−1) to measure F′m (Beer et al. 1998). Each yield value used in the analyses was a mean of three replicate measurements taken on different parts of each algal sample, so that yield was not underestimated owing to the recovery of the photosystems from repeated saturating light pulses.

Turf specimens used in experiments were collected from a rocky reef at Victor Harbour, South Australia (35.57126° S, 138.61221° E) at 2–4 m depth. The turf assemblages used comprised mainly Feldmannia spp., which form densely packed mats of filaments up to 2 cm in height. Turfs were collected still attached to their rocky substrate (approximately the same size, 5 × 5 cm) and allowed to acclimate in holding mesocosms for two weeks before the experiment commenced. During acclimation, physical conditions in the mesocosms were similar to those at the collection site (i.e. 17°C and current atmospheric CO2 concentrations). Algae were then randomly reassigned to mesocosms in which experimental conditions were gradually increased over a further two-week period until they reached their pre-designated levels. All mesocosms were aerated at 10 l min−1, with either current atmospheric air or air enriched with CO2. Future concentrations of CO2 in water were maintained at 550 ppm CO2 (pH 7.95, based on the IS92a model for 2050; Meehl et al. 2007) using pH probes attached to automatic solenoids (Sera, Heinsberg, Germany) and CO2 regulators. Probes were temperature-compensated and calibrated using National Bureau of Standards (NBS) calibration buffers on a daily basis. Elevated temperature was achieved by using heaters in the 20°C treatment mesocosms. Total alkalinity of the sea water in mesocosms was measured on a weekly basis to monitor CO2 and bicarbonate ( ) concentrations (see electronic supplementary material for more details).

) concentrations (see electronic supplementary material for more details).

Each mesocosm system consisted of a 40 l experimental aquarium connected to a 200 l reservoir tank with water recirculated in a closed loop, ensuring that all replicate mesocosms were independent of each other. To ensure quality of the growing conditions in mesocosms, one-third of the water was removed from reservoir tanks and replaced with fresh sea water weekly (see Russell et al. 2009). Lighting was supplied in a 12 : 12 light : dark cycle by pairs of fluorescent lights directly above each mesocosm (see electronic supplementary material for more details).

(c). Statistical analyses

The effect of turf on kelp recruitment was analysed using a two-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA), with factors of turf (turf present versus turf removed) and site (three sites). Both factors were treated as orthogonal, ‘turf’ as fixed and ‘site’ as random (n = 12 replicate plots). Data were ln (X + 1) transformed before analysis to conform to assumptions of homogeneity.

Analysis of the mesocosm experiment proceeded in two steps. First, three-factor ANOVAs were used to identify whether there was any difference in experimental effects between replicate mesocosms for all measures (percentage cover, dry mass and effective quantum yield). Both CO2 and temperature were treated as fixed and orthogonal, with two levels in each factor, and two replicate mesocosms were nested within both CO2 and temperature (n = 5 replicate samples of algae per mesocosm). No differences were detected between replicate mesocosms within treatments (i.e. no ‘tank’ effects). Therefore, to avoid pseudoreplication within mesocosms, data for the five algal specimens within each mesocosm were averaged, and data reanalysed using two-factor ANOVAs; CO2 and temperature were again treated as fixed and orthogonal, with mesocosms as replicates. Where significant treatment effects were detected, Student–Newman–Keuls (SNK) post hoc comparison of means was used to determine which factors differed. Percentage cover data were arcsine transformed prior to analysis to remove heterogeneity (Underwood 1981).

3. Results

(a). Ability of turfs to inhibit kelp recruitment

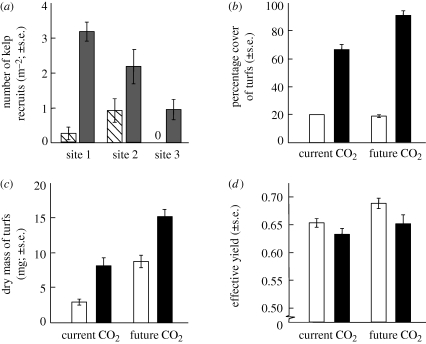

The removal of turfs resulted in the greater recruitment of kelp at all three phase-shifted sites (figure 1a). While there was significant difference in the number of kelp recruits among the three replicate sites, the number of kelp recruits was consistently greater in removal plots than plots were turfs were left intact (turf removal × site interaction: F2,66 = 6.10, p = 0.0037; SNK: turf removal > turf intact at all three sites).

Figure 1.

(a) The inhibitory effect of turf on recruitment of kelp at three phase-shifted sites (i.e. kelp domination to turf domination) with treatments of turf presence and turf removal, and the effect of forecasted CO2 and temperature on turfs as observed by (b) recruitment to available space (percentage cover), (c) biomass (dry mass) and (d) effective quantum yield. Note: ‘0’ in (a) signifies no kelp recruits. Striped bar, turf present; grey bar, turf removed; white bar, 17°C; black bar, 20°C.

(b). Effect of future conditions on turfs

CO2 and temperature had an interactive effect on the percentage cover of turf-forming algae that recruited to available space (figure 1b; CO2 × temperature interaction, F1,4 = 7.73, p = 0.0498). Under current CO2 concentrations, temperature had a positive effect on the percentage cover of turfs that recruited to available space (figure 1b; SNK test of CO2 × temperature interaction). In contrast, future CO2 had no effect on the cover of turfs at ambient temperatures (17°C). When future CO2 and elevated temperature were present in combination, however, turfs occupied greater than 80 per cent of available space (figure 1b). Importantly, this represented a synergistic effect whereby turfs occupied 25 per cent more space than would be predicted by the independent effects of CO2 and temperature.

Both elevated CO2 and temperature had positive effects on the dry mass of turfs (figure 1c; F1,4 = 19.20, p = 0.0119 and F1,4 = 11.39, p < 0.0279, respectively). There is no graphical evidence of an interaction between these factors (figure 1c) as the increase in mass by CO2 is proportionally similar between the CO2 treatments, and vice versa. This interpretation is supported by the lack of a significant interaction term between these factors (F1,4 = 0.41, p = 0.5558; power = 0.08), as shown by the effect of temperature in each CO2 treatment (approximately double the mass) and the effect of CO2 in each temperature treatment (approximately double the mass) (figure 1c). Hence, the combined effects of CO2 and temperature are approximately four times greater than ambient conditions.

The effects of these factors on quantum yield were relatively small; yield of turfs was 5 per cent greater under future CO2 concentrations (figure 1d; ANOVA: F1,4 = 14.11, p = 0.0198) but 3 per cent less under elevated temperature (figure 1d; F1,4 = 16.73, p = 0.0150). Again, the proportional influence of each factor was similar within each level of the crossed factor (figure 1d), as also indicated by the lack of a significant interaction term between these factors (F1,4 = 1.24, p = 0.3276; power = 0.14). While we report low power for non-significant interactions, we consider the combined effects of temperature and CO2 are indeed additive rather than multiplicative.

4. Discussion

A substantial part of research into global environmental change centres on the negative effects of ocean acidification and increasing temperature on organisms that form calcareous structures (e.g. Fabry et al. 2008; Jokiel et al. 2008; Kuffner et al. 2008). While elevated CO2 can be beneficial to plants in terrestrial systems (Ainsworth & Long 2005), there is little recognition of the positive effects on some non-calcareous marine species. Here, we show that predicted moderate concentrations of CO2 and temperature had a synergistic positive effect on the abundance of non-calcareous algal turfs. Yet it is important to recognize that such positive effects could act as perturbations in ecological systems. Turfs form a natural component of the early successional stages of kelp-dominated landscapes. Under natural conditions, algal canopies inhibit these algae (Irving & Connell 2006; Eriksson et al. 2007; Russell 2007), but under altered environmental conditions turfs expand (Connell 2007; Russell & Connell 2007) by inhibiting kelp recruitment (i.e. eroding resilience of forests). Our results indicate that kelp loss may be exacerbated, on human-dominated coasts, by the positive effects of increasing CO2 and temperature on kelp inhibitors, motivating the need to assess such switches on coasts that are currently considered unaffected by human activity.

Recruitment that replenishes lost habitat-forming individuals is key to resilience against phase shifts in ecosystems founded on habitat-forming species (Pickett & White 1985). Disturbance is part of the dynamics of kelp forests which would otherwise fully occupy space (e.g. storms; Dayton et al. 1984). We recognize that it is not so much the direct effects of climate stressors on kelp forests that may affect their future abundance, but rather the indirect loss of kelp via their competitors or inhibitors. Altering global (i.e. CO2) and local (i.e. eutrophication) stressors in combination can allow turfs to expand to more rapidly occupy available space (Russell et al. 2009). It is noteworthy that our experimentally increased CO2 and temperature, two inherently linked global stressors, enabled turfs to occupy nearly five times more space than under current conditions. While it may be possible to mitigate the effects of climate-driven environmental change by removing nutrient inputs (e.g. recycling wastewater and sewage; Russell & Connell 2009), such actions would not be possible in the case of synergistic effects between multiple global stressors. Indeed, understanding the degree to which these factors will combine to accelerate and expand ecosystem shifts is of key concern (Scheffer et al. 2001; Suding & Hobbs 2009).

Increasing temperatures are commonly predicted to result in changes in marine communities because of a shift in the geographical ranges of species (e.g. Fields et al. 1993; Poloczanska et al. 2008). While community shifts have been observed, local conditions and competitive interactions may alter the outcomes (Helmuth et al. 2002; Poloczanska et al. 2008). In such cases, taxa that are natural components of a system may play substantially altered roles in their maintenance and disruption (Suding & Hobbs 2009). In Australia, E. radiata canopies have high rates of natural turnover, and their maintenance relies on rapid recruitment and replenishment into canopy gaps in the winter months (Kennelly 1987b). While turfs are a natural component of these kelp-dominated systems (Irving et al. 2004), they are ephemeral, rapidly occupying available space in summer but declining in cover and biomass over the colder months (Russell & Connell 2005; S. D. Connell, B. D. Russell, D. Gorman & A. Airoldi 2005–2006, unpublished data). Importantly, E. radiata produce gametophytes, the smallest and therefore more susceptible stage of the life cycle, in the colder months when turfs are at their lowest abundance. Yet, we show that turfs increased in abundance under elevated temperatures, suggesting that future increases in temperature could allow turfs to be increasingly abundant throughout periods of naturally low abundance (i.e. winter). Similarly, turfs exhibit a phenological shift owing to elevated nutrients (S. D. Connell, B. D. Russell, D. Gorman & A. Airoldi 2005–2006, unpublished data), possibly leading to habitat shifts on urbanized coasts (Gorman et al. 2009). As algal turfs can inhibit kelp recruitment (Kennelly 1987a; this study), any phenological shift that allows turfs to persist though periods of kelp recruitment is likely to reduce the resilience of kelp forests to disturbance. While it is accepted that such habitat shifts are common on human-dominated coasts (Airoldi 2003; Connell 2007), temperature, unlike nutrients, will increase even on ‘pristine’ coasts, potentially causing habitat shifts in the absence of local human populations.

Loss of canopy-forming algae can be a consequence of overgrazing by increasing urchin populations (Estes et al. 1998), but in many parts of the world, including most of southern Australia, such deforestation is not possible because of the types and sparse densities of herbivores (Connell & Vanderklift 2007; Connell & Irving 2008). Nevertheless, canopy-forming algae have long been disappearing from human-dominated coasts lacking strong herbivory, but experiencing strong water pollution (Eriksson et al. 2002; Airoldi et al. 2008; Connell et al. 2008); yet the specific mechanisms underlying this loss are often a point of conjecture and contention. Previous studies have demonstrated that some more erect forms of turf-forming and foliose algae can dominate available space and inhibit canopy recruitment (Kennelly 1987a; Airoldi 2003), but, to our knowledge, ours is the first study to show that the removal of filamentous turfs can enhance the recruitment of kelp. By removing turfs from the substrate, we created more available space for kelp recruits to settle and become established. As the creation of new space is a prerequisite for community change (Pickett & White 1985; Airoldi & Virgilio 1998), it is unlikely that these phase-shifted reefs (i.e. from kelp to turf dominated; Connell et al. 2008) will be able to return to domination by kelp canopies until the environmental conditions on these coasts revert to their more natural state (e.g. nutrients; Gorman et al. 2009). Nevertheless, we demonstrate that the removal of turfs can create the space necessary for the recruitment and recovery of kelp and that the observed phase shift (Connell et al. 2008) may not be permanent.

While the productivity of terrestrial plants stands to increase with predicted future CO2, especially in plants that use C3 photosynthesis (Ainsworth & Long 2005), there is still debate on whether this will be the case in marine algae. Most marine algae have carbon-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) that allow them to use bicarbonate for photosynthesis, meaning that photosynthesis is carbon saturated at current concentrations (Gao & McKinley 1994; Beardall et al. 1998). Experiments have so far been inconclusive, with some species showing carbon saturation at current CO2 (e.g. Beer & Koch 1996; Israel & Hophy 2002), others demonstrating increased photosynthetic production with increasing CO2 (e.g. Holbrook et al. 1988), and yet others switching the source of carbon with greater CO2 availability (e.g. Johnston & Raven 1990; Schmid et al. 1992). Yet general consensus within the literature seems to be that algae with CCMs will not increase productivity under future conditions (see review by Beardall et al. 1998). It is no surprise, then, that the positive effects of CO2 on algae have not been a substantial part of the climate change literature; if productivity is not enhanced by elevated CO2, then why look for ecological effects? Our experiments do not clarify this issue with respect to photosynthetic activity of algae; we found a small increase (approx. 5%) in the effective quantum yield of turfs under future concentrations of CO2, but this seemed to be counteracted by elevated temperature. Nevertheless, it seems that elevated CO2 conditions can cause an increase in the growth (Kubler et al. 1999) and abundance (Andersen & Andersen 2006; Kuffner et al. 2008; Russell et al. 2009) of non-calcareous algae, and this deserves more attention. We propose that elevated inorganic carbon has positive effects on some taxa, and that the non-uniform effects among alternate taxa (review by Gao & McKinley 1994) have relatively unexplored ecological consequences, particularly if growth is limited by sources of inorganic carbon.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to J. Thompson and I. Bunker for assistance in the laboratory and D. Gorman in the field. Financial support for this research was provided by an ARC grant to B.D.R. and S.D.C., and an ARC Fellowship to S.D.C.

References

- Ainsworth E. A., Long S. P.2005What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 165, 351–371 (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi L.2003The effects of sedimentation on rocky coast assemblages. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 41, 161–236 [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi L., Beck M. W.2007Loss, status and trends for coastal marine habitats of Europe. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 45, 345–405 [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi L., Virgilio M.1998Responses of turf-forming algae to spatial variations in the deposition of sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 165, 271–282 (doi:10.3354/meps165271) [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi L., Balata D., Beck M. W.2008The Gray Zone: relationships between habitat loss and marine diversity and their applications in conservation. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 366, 8–15 (doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.07.034) [Google Scholar]

- Andersen T., Andersen F. O.2006Effects of CO2 concentration on growth of filamentous algae and Littorella uniflora in a Danish softwater lake. Aquat. Bot. 84, 267–271 (doi:10.1016/j.aquabot.2005.09.009) [Google Scholar]

- Anthony K. R. N., Kline D. I., Diaz-Pulido G., Dove S., Hoegh-Guldberg O.2008Ocean acidification causes bleaching and productivity loss in coral reef builders. PNAS 105, 17 442–17 446 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0804478105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardall J., Beer S., Raven J. A.1998Biodiversity of marine plants in an era of climate change: some predictions based on physiological performance. Bot. Mar. 41, 113–123 (doi:10.1515/botm.1998.41.1-6.113) [Google Scholar]

- Beer S., Koch E.1996Photosynthesis of marine macroalgae and seagrasses in globally changing CO2 environments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 141, 199–204 (doi:10.3354/meps141199) [Google Scholar]

- Beer S., Vilenkin B., Weil A., Veste M., Susel L., Eshel A.1998Measuring photosynthetic rates in seagrasses by pulse amplitude modulated (PAM) fluorometry. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 174, 293–300 (doi:10.3354/meps174293) [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M., Ho M., Selvakumaraswamy P., Nguyen H. D., Dworjanyn S. A., Davis A. R.2009Temperature, but not pH, compromises sea urchin fertilization and early development under near-future climate change scenarios. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1883–1888 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1935) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell S. D.2007Water quality and the loss of coral reefs and kelp forests: alternative states and the influence of fishing. In Marine ecology (eds Connell S. D., Gillanders B. M.), pp. 556–568 Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Connell S. D., Irving A. D.2008Integrating ecology with biogeography using landscape characteristics: a case study of subtidal habitat across continental Australia. J. Biogeogr. 35, 1608–1621 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.01903.x) [Google Scholar]

- Connell S. D., Vanderklift M. A.2007Negative interactions: the influence of predators and herbivores on prey and ecological systems. In Marine ecology (eds Connell S. D., Gillanders B. M.), pp. 72–100 Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Connell S. D., Russell B. D., Turner D. J., Shepherd S. A., Kildea T., Miller D., Airoldi L., Cheshire A.2008Recovering a lost baseline: missing kelp forests from a metropolitan coast. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 360, 63–72 (doi:10.3354/meps07526) [Google Scholar]

- Dayton P. K., Currie V., Gerrodette T., Keller B. D., Rosenthal R., Ventresca D.1984Patch dynamics and stability of some California kelp communities. Ecol. Monogr. 54, 253–289 (doi:10.2307/1942498) [Google Scholar]

- Drummond S. P., Connell S. D.2005Quantifying percentage cover of subtidal organisms on rocky coasts: a comparison of the costs and benefits of standard methods. Mar. Freshw. Res. 56, 865–876 (doi:10.1071/MF04270) [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S., Havenhand J., Thorndyke W., Peck L., Thorndyke M.2008Near-future level of CO2-driven ocean acidification radically affects larval survival and development in the brittlestar Ophiothrix fragilis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 285–294 (doi:10.3354/meps07800) [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B. K., Johansson G., Snoeijs P.2002Long-term changes in the macroalgal vegetation of the inner Gullmar Fjord, Swedish Skagerrak coast. J. Phycol. 38, 284–296 (doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.00170.x) [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B. K., Rubach A., Hillebrand H.2007Dominance by a canopy forming seaweed modifies resource and consumer control of bloom-forming macroalgae. Oikos 116, 1211–1219 (doi:10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15666.x) [Google Scholar]

- Estes J. A., Tinker M. T., Williams T. M., Doak D. F.1998Killer whale predation on sea otters linking oceanic and nearshore ecosystems. Science 282, 473–476 (doi:10.1126/science.282.5388.473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabry V. J., Seibel B. A., Feely R. A., Orr J. C.2008Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 65, 414–432 (doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsn048) [Google Scholar]

- Feely R. A., Sabine C. L., Lee K., Berelson W., Kleypas J., Fabry V. J., Millero F. J.2004Impact of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCO3 system in the oceans. Science 305, 362–366 (doi:10.1126/science.1097329) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields P. A., Graham J. B., Rosenblatt R. H., Somero G. N.1993Effects of expected global climate change on marine faunas. Trends Ecol. Evol. 8, 361–367 (doi:10.1016/0169-5347(93)90220-J) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., McKinley K. R.1994Use of macroalgae for marine biomass production and CO2 remediation: a review. J. Appl. Phycol. 6, 45–60 (doi:10.1007/BF02185904) [Google Scholar]

- Genty B., Briantais J. M., Baker N. R.1989The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 990, 87–92 [Google Scholar]

- Gorman D., Russell B. D., Connell S. D.2009Land-to-sea connectivity: linking human-derived terrestrial subsidies to subtidal habitat change on open rocky coasts. Ecol. Appl. 19, 1114–1126 (doi:10.1890/08-0831.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmuth B., Harley C. D. G., Halpin P. M., O'Donnell M., Hofmann G. E., Blanchette C. A.2002Climate change and latitudinal patterns of intertidal thermal stress. Science 298, 1015–1017 (doi:10.1126/science.1076814) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh-Guldberg O., et al. 2007Coral reefs under rapid climate change and ocean acidification. Science 318, 1737–1742 (doi:10.1126/science.1152509) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook G. P., Beer S., Spencer W. E., Reiskind J. B., Davis J. S., Bowes G.1988Photosynthesis in marine macroalgae—evidence for carbon limitation. Can. J. Bot. Rev. Can. Bot. 66, 577–582 [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T. P., et al. 2007Phase shifts, herbivory, and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr. Biol. 17, 360–365 (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving A. D., Connell S. D.2002Interactive effects of sedimentation and microtopography on the abundance of subtidal turf-forming algae. Phycologia 41, 517–522 [Google Scholar]

- Irving A. D., Connell S. D.2006Physical disturbance by kelp abrades erect algae from the understorey. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 324, 127–137 (doi:10.3354/meps324127) [Google Scholar]

- Irving A. D., Connell S. D., Gillanders B. M.2004Local complexity in patterns of canopy–benthos associations produces regional patterns across temperate Australasia. Mar. Biol. 144, 361–368 (doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1202-9) [Google Scholar]

- Israel A., Hophy M.2002Growth, photosynthetic properties and Rubisco activities and amounts of marine macroalgae grown under current and elevated seawater CO2 concentrations. Glob. Change Biol. 8, 831–840 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00518.x) [Google Scholar]

- Johnston A. M., Raven J. A.1990Effects of culture in high CO2 on the photosynthetic physiology of Fucus serratus. Br. Phycol. J. 25, 75–82 (doi:10.1080/00071619000650071) [Google Scholar]

- Jokiel P. L., Rodgers K. S., Kuffner I. B., Andersson A. J., Cox E. F., Mackenzie F. T.2008Ocean acidification and calcifying reef organisms: a mesocosm investigation. Coral Reefs 27, 473–483 (doi:10.1007/s00338-008-0380-9) [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly S. J.1987aInhibition of kelp recruitment by turfing algae and consequences for an Australian kelp community. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 112, 49–60 (doi:10.1016/S0022-0981(87)80014-X) [Google Scholar]

- Kennelly S. J.1987bPhysical disturbances in an Australian kelp community. I. Temporal effects. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 40, 145–153 (doi:10.3354/meps040145) [Google Scholar]

- Kubler J. E., Johnston A. M., Raven J. A.1999The effects of reduced and elevated CO2 and O2 on the seaweed Lomentaria articulata. Plant Cell Environ. 22, 1303–1310 (doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.1999.00492.x) [Google Scholar]

- Kuffner I. B., Andersson A. J., Jokiel P. L., Rodgers K. S., Mackenzie F. T.2008Decreased abundance of crustose coralline algae due to ocean acidification. Nat. Geosci. 1, 114–117 (doi:10.1038/ngeo100) [Google Scholar]

- Mann K. H.1973Seaweeds: their productivity and strategy for growth. Science 182, 975–981 (doi:10.1126/science.182.4116.975) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S., Gattuso J. P.2009Response of Mediterranean coralline algae to ocean acidification and elevated temperature. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 2089–2100 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01874.x) [Google Scholar]

- Meehl G. A., et al. 2007Global climate projections. In Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Solomon S., Qin D., Manning M., Chen Z., Marquis M., Averyt K. B., Tignor M., Miller H. L.), pp. 747–845 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Orr J. C., et al. 2005Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681–686 (doi:10.1038/nature04095) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker L. M., Ross P. M., O'Connor W. A.2009The effect of ocean acidification and temperature on the fertilisation and embryonic development of the Sydney rock oyster Saccostrea glomerata (Gould 1850). Glob. Change Biol. 15, 2123–2136 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01895.x) [Google Scholar]

- Pickett S. T. A., White P. S. (ed.) 1985The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Poloczanska E. S., Hawkins S. J., Southward A. J., Burrows M. T.2008Modeling the response of populations of competing species to climate change. Ecology 89, 3138–3149 (doi:10.1890/07-1169.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. D.2007Effects of canopy-mediated abrasion and water flow on the early colonisation of turf-forming algae. Mar. Freshw. Res. 58, 657–665 (doi:10.1071/MF06194) [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. D., Connell S. D.2005A novel interaction between nutrients and grazers alters relative dominance of marine habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 289, 5–11 (doi:10.3354/meps289005) [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. D., Connell S. D.2007Response of grazers to sudden nutrient pulses in oligotrophic v. eutrophic conditions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 349, 73–80 (doi:10.3354/meps07097) [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. D., Connell S. D.2009Eutrophication science: moving into the future. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 527–528 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell B. D., Thompson J. I., Falkenberg L. J., Connell S. D.2009Synergistic effects of climate change and local stressors: CO2 and nutrient driven change in subtidal rocky habitats. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 2153–2162 (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01886.x) [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer M., Carpenter S., Foley J. A., Folke C., Walker B.2001Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 413, 591–596 (doi:10.1038/35098000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid R., Forster R., Dring M. J.1992Circadian rhythm and fast responses to blue-light of photosynthesis in Ectocarpus (Phaeophyta, Ectocarpales). II. Light and CO2 dependence of photosynthesis. Planta 187, 60–66 (doi:10.1007/BF00201624) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith V. H., Schindler D. W.2009Eutrophication science: where do we go from here? Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 201–207 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.11.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suding K. N., Hobbs R. J.2009Threshold models in restoration and conservation: a developing framework. Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 271–279 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.11.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood A. J.1981Techniques of analysis of variance in experimental marine biology and ecology. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Annu. Rev. 19, 513–605 [Google Scholar]

- van Kooten O., Snel J. F. H.1990The use of chlorophyll fluorescence nomenclature in plant stress physiology. Photosynth. Res. 25, 147–150 (doi:10.1007/BF00033156) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]