Abstract

Androgens act to stimulate spermatogenesis through androgen receptors (ARs) on the Sertoli cells and peritubular myoid cells. Specific ablation of the AR in either cell type will cause a severe disruption of spermatogenesis. To determine whether androgens can stimulate spermatogenesis through direct action on the peritubular myoid cells alone or whether action on the Sertoli cells is essential, we crossed hypogonadal (hpg) mice that lack gonadotrophins and intratesticular androgen with mice lacking ARs either ubiquitously (ARKO) or specifically on the Sertoli cells (SCARKO). These hpg.ARKO and hpg.SCARKO mice were treated with testosterone (T) or dihydrotestosterone (DHT) for 7 d and testicular morphology and cell numbers assessed. Androgen treatment did not affect Sertoli cell numbers in any animal group. Both T and DHT increased numbers of spermatogonia and spermatocytes in hpg mice, but DHT has no effect on germ cell numbers in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice. T increased germ cell numbers in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice, but this was associated with stimulation of FSH release. Results show that androgen stimulation of spermatogenesis requires direct androgen action on the Sertoli cells.

Androgens must act through Sertoli cell androgen receptors to stimulate spermatogenesis.

Spermatogenesis is regulated by FSH and androgen released from the Leydig cells in response to LH. In mice lacking androgen receptors (ARs) through either a natural mutation (Tfm) or genomic manipulation (ARKO), there is severe disruption to spermatogenesis with a failure of germ cells to progress beyond the early stages of meiosis (1,2). In contrast, mice lacking FSH or the FSH receptor are fertile, albeit with reduced germ cell number (3,4,5,6), indicating that FSH acts primarily to optimize spermatogenesis and germ cell number, whereas androgens are critical for the completion of meiosis and therefore fertility.

In the adult animal, testicular ARs are expressed in Sertoli cells, Leydig cells, and peritubular myoid cells (PTMs) (2). The primary function of the Sertoli cells is to promote and maintain germ cell development through direct interaction with the cells and generation of a unique microenvironment within the lumen of the seminiferous tubules. In mice lacking ARs only in the Sertoli cells (SCARKO), spermatogenesis is largely blocked at meiosis (2,7,8), although the disruption to spermatogenesis in the SCARKO is less marked than in the Tfm or ARKO mouse. In addition to the SCARKO mouse, it has recently been reported that mice lacking ARs in the PTMs (PTM-ARKO) show severe depletion of germ cell numbers and are infertile (9). This shows that androgen action through the PTMs is also essential for spermatogenesis and reveals a more complex interplay between endocrine stimulation, somatic cell activity, and spermatogenesis than previously envisioned.

To examine these interactions more closely and determine whether androgen can acutely stimulate spermatogenesis without a direct effect on the Sertoli cell, we generated mice lacking gonadotrophins and Sertoli cell ARs by crossing SCARKO mice with hypogonadal (hpg) mice. The hpg mouse lacks circulating gonadotrophins (10) with a consequent loss of androgen production (11) and disruption to spermatogenesis (10). Treatment of hpg.SCARKO mice with androgen will directly stimulate all androgen-sensitive testicular cells apart from the Sertoli cell and show whether direct androgen action on the Sertoli cells is essential for germ cell development.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

All mice were bred and all procedures carried out under U.K. Home Office license and with the approval of a local ethical review committee. SCARKO and ARKO mice have been previously generated by crossing female mice carrying an Ar with a floxed exon 2 (Arfl) with male mice expressing Cre under the regulation of the Sertoli cell specific promoter Amh or the ubiquitous promoter Pgk-1 (2,12). The hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice were generated as previously described (6,13).

Adult mice (10 wk) were treated with androgen by sc implantation of a 2-cm SILASTIC brand capsule (Dow Corning, Midland, MI; internal diameter 1.98 mm) containing testosterone (T) or the nonaromatizable androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Serum androgen levels have been shown previously to reach maximum within 48 h of implantation and to be maintained for more than 40 d (14). Mice were killed 1 wk after the start of treatment and testes snap frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed overnight. Fixation was either in 4% paraformaldehyde/1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.4) for preparation of semithin sections or in Bouin’s for subsequent morphometric analysis or immunohistochemistry.

Hormone measurement

Serum levels of FSH were measured by ELISA (IDS, Bolden, UK).

Histology, stereology, and immunohistochemistry

To prepare semithin (1 μm) sections, testes were embedded in araldite and sections stained with toluidine blue. For stereological analysis, testes were embedded in Technovit 7100 resin, cut into sections (20 μm), and stained with Harris’ hematoxylin. The total testis volume was estimated using the Cavalieri principle (15). The optical dissector technique (16) was used to count the number of Sertoli cells and germ cells in each testis. Each cell type was identified by previously described criteria (17,18). The numerical density of each cell type was estimated using an Olympus BX50 microscope fitted with a motorized stage (Prior Scientific Instruments, Cambridge, UK) and Stereologer software (Systems Planning Analysis, Alexandria, VA). Control data for this study include data from a previous study (6) plus additional animals.

For immunohistochemistry, testes were embedded in paraffin and sections (5 μm) were mounted on glass slides, dewaxed, and rehydrated. Sections were incubated with rabbit anti-AR antiserum (sc-816; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) after heat-induced antigen retrieval (2). Bound primary antibody was detected using a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, followed by a fluorescyl-tyramide amplification step with visualization using 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Dako UK Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK). For negative control samples, nonimmune serum replaced primary antiserum.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using two-factor ANOVA, with hormone treatment and animal group as the two variables. To show whether differences between individual groups were significant, t tests were used using the pooled variance from the ANOVA. Data were log transformed where appropriate to avoid heterogeneity of variance. Data on FSH levels were analyzed by the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test.

Results

AR expression

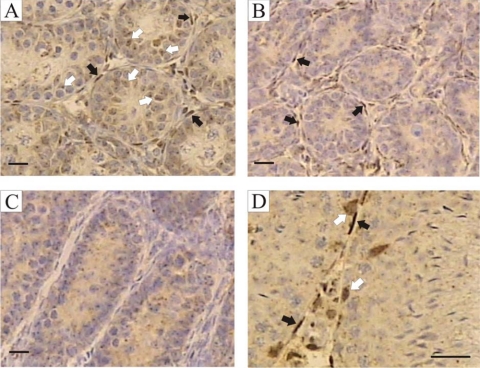

Immunohistochemistry was used to localize ARs in the testes of hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO mice (Fig. 1). In the hpg testis, ARs were clearly present in the PTMs and interstitial tissue with lighter staining apparent in the Sertoli cells (Fig. 1A). In hpg.SCARKO mice, there was clear staining for ARs in the PTMs and interstitial tissue, whereas no specific staining was seen in the hpg.ARKO mice (Fig. 1, B and C). For comparison, testes from normal mice were included and AR expression was apparent in Sertoli cells, PTMs, and interstitial tissue (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Localization of AR expression. Immunohistochemistry was used to localize AR expression in adult testes from hpg (A), hpg.SCARKO (B), hpg.ARKO (C), and normal mice (D). In the hpg testis, ARs were clearly present in the PTMs (black arrows) and interstitial tissue with lighter staining apparent in the Sertoli cells (white arrows, cells identified by their nuclear shape and more prominent nucleolus). In hpg.SCARKO mice, there was clear staining for ARs in the PTMs (black arrows) and interstitial tissue, whereas no specific staining was seen in the hpg.ARKO mice. Apparent staining in the tubules is background staining. In normal mice, AR expression was apparent in Sertoli cells, PTMs, and interstitial tissue. Bar, 20 μm.

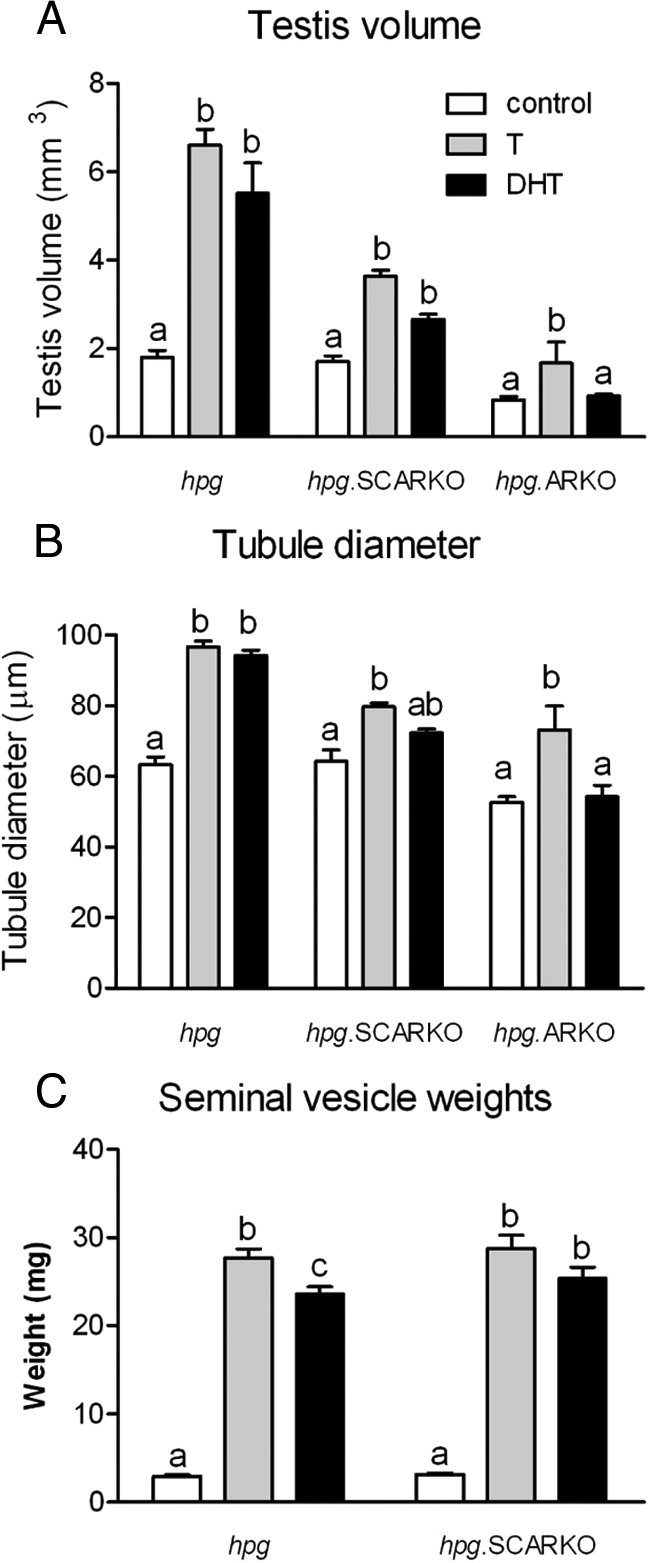

Effect of androgen on testis size, testis morphology, and seminal vesicle weight

Hypogonadal mice are cryptorchid due to lack of postnatal androgen production. Prolonged androgen treatment of these animal will induce testicular descent, but the duration of treatment in the experiments described here was insufficient to affect testicular localization. Treatment of hpg and hpg.SCARKO mice with T or DHT did, however, increase testicular volume with the effect on hpg mice being more marked (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, T also increased the volume of hpg.ARKO mice but there was no effect of DHT (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of androgen on testis volume (A), tubule diameter (B), and seminal vesicle weight (C) in hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO mice. Adult mice were treated with T or DHT for 7 d. Results show the mean ± sem for three to six animals per group in A and B and nine to 36 animals per group in C. Within a particular animal type, groups with different letter superscripts were significantly (P < 0.05) different.

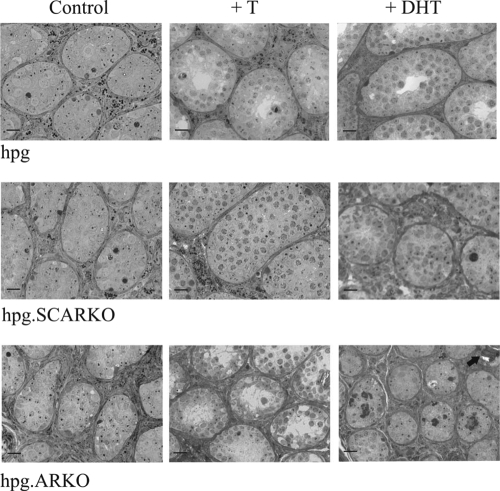

Treatment of hpg mice with T or DHT caused an increase in seminiferous tubule diameter (Figs. 2 and 3), clear establishment of a tubular lumen, and an apparent increase in germ cell number (Fig. 3). In some tubules, spermatogenesis progressed to the round spermatid stage after treatment with T (Fig. 3). T also increased tubule diameter in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice, but DHT had an effect only in hpg.SCARKO mice (Figs. 2 and 3).

Figure 3.

Semithin sections showing the effect of androgen on testicular morphology in hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO mice. In untreated animals, spermatogenesis was severely disrupted with only spermatogonia and some spermatocytes present. Treatment with T increased germ cell numbers in all mice, although the effect was most marked in the hpg. Treatment with DHT increased germ cell number only in the hpg. In the hpg.ARKO group, black arrows indicate the presence of microliths (13). Bar, 20 μm.

Seminal vesicle weights were significantly increased by T and DHT in both hpg and hpg.SCARKO mice (Fig. 2). Due to a lack of ARs, seminal vesicles do not develop in hpg.ARKO mice.

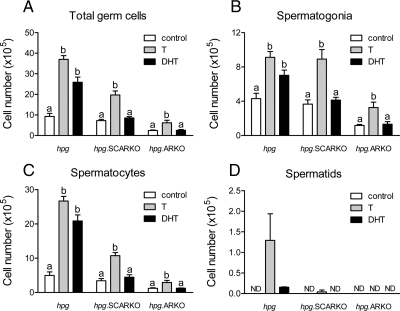

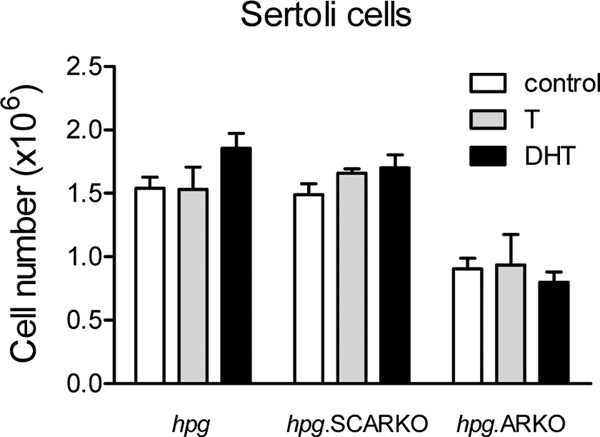

Stereology

Sertoli cell number was unaffected by androgen treatment in any animal group (Fig. 4). Total germ cell number was increased by T in all three animal groups (Fig. 5). In contrast, DHT increased total germ cell number in hpg mice but had no effect on hpg.SCARKO or hpg.ARKO mice (Fig. 5). Similarly, T and DHT both increased spermatogonial and spermatocyte numbers in hpg mice, but only T was effective in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice. Formation of round spermatids was limited mainly to hpg mice treated with T (Fig. 5). A very small number of round spermatids were formed in hpg mice treated with DHT and hpg.SCARKO mice treated with T (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Effect of androgen on Sertoli cell number in hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO mice. Adult mice were treated with T or DHT for 7 d and cell numbers counted as described in Materials and Methods. Results show the mean ± sem for three to six animals per group. Within a particular animal type, there were no significant differences in Sertoli cell number.

Figure 5.

Effect of androgen treatment on the number of total germ cells (A), spermatogonia (B), spermatocyte (C), and spermatids (D) in hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO mice. Adult mice were treated with T or DHT for 7 d and cell numbers counted as described in Materials and Methods. Results show the mean ± sem for three to six animals per group. Within a particular animal type, groups with different letter superscripts were significantly (P < 0.05) different. No statistical analysis was applied to spermatid numbers. ND, Not detected.

FSH levels

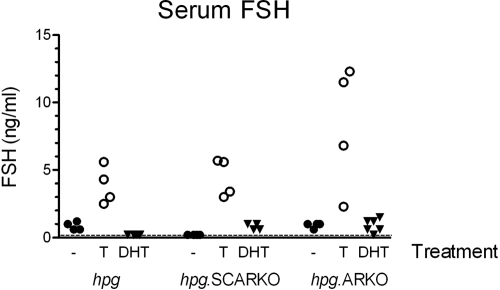

Serum FSH levels in hpg and hpg.ARKO mice were all less than 1.5 ng/ml, and in hpg.SCARKO mice, all levels were below the level of detection of the assay (0.2 ng/ml) (Fig. 6). For comparison, serum FSH levels in normal adult male mice are about 25 ng/ml (19). Treatment of hpg, hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice with T caused a significant increase in serum FSH, but DHT had no clear effect (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Serum levels of FSH in hpg, hpg.SCARKO, and hpg.ARKO males treated with T or DHT for 7 d. Results show values from individual animals in each group. The effect of testosterone was significant (P < 0.05) in all three groups.

Discussion

Studies with mice lacking functional ARs (Tfm or ARKO) have shown clearly that androgen is essential for the onset of spermatogenesis (1,2). In addition, there is strong evidence from other models to indicate that androgens are critical for the maintenance of spermatogenesis. For example, testosterone withdrawal appears to induce apoptosis of pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids (20), and there is growing evidence that androgens are required for postmeiotic germ cell adhesion to the Sertoli cell (21,22,23). Because Sertoli cells express AR (24), germ cells do not express AR (24,25), and Sertoli cells are intimately involved in germ cell development, it has appeared likely for some time that the major effects of androgen are mediated through the Sertoli cells. This has been reenforced by the testicular phenotype of the SCARKO mouse, which lacks germ cell development beyond the first meiotic division (2). It is of considerable interest therefore that a recent study reported major disruption to spermatogenesis in mice lacking AR in the PTMs (9). Total loss of germ cells in these animals was greater than in SCARKO mice and appeared to be largely through disruption of the premeiotic cells (9). The results are all the more surprising because Cre expression (and therefore AR ablation) occurred in less than 50% of PTMs. It is now clear therefore that androgens act to promote spermatogenesis through actions on both Sertoli cells and PTMs. To study this dual control in more detail, we used animal models based on the hpg mouse, which lacks germ cell development and is highly sensitive to androgen action (26,27). By combining hpg mice with SCARKO mice, we have been able to determine whether androgens can stimulate spermatogenesis without direct effects through AR in the Sertoli cell. Results show that (nonaromatizable) androgen action through the PTMs (and Leydig cells) alone is insufficient to stimulate spermatogenesis in these animals and that direct androgen action on the Sertoli cells is essential.

The requirement for direct androgen action on the Sertoli cell to stimulate spermatogenesis may appear to be obvious from the phenotype of the SCARKO mouse (2). The major defect in this animal, however, is loss of postmeiotic cells, and this does not rule out additional direct spermatogenic effects of androgen through other cell types. In particular, premeiotic germ cell numbers are not markedly affected in the SCARKO mouse [spermatogonial numbers are normal and spermatocyte numbers are about 50–60% of normal (2,28)], indicating that androgen action through other cells combined with FSH action on the Sertoli cells is sufficient to maintain reasonable premeiotic germ cell numbers. The phenotype of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor knockout and PTM-ARKO mice, and the effects of FSH on the hpg would also be consistent with this hypothesis (3,6,9). In data reported here, however, the failure of DHT to stimulate tubule and germ cell development in the hpg.SCARKO mouse, in comparison with the hpg mouse, shows that androgen stimulation of spermatogonial and spermatocyte development requires direct action on the Sertoli cells. These experiments do not rule out the possibility that androgen action through the PTMs is also essential to stimulate spermatogenesis and studies using hpg.PTM-ARKO mice would clarify this. Indeed, the increase in hpg.SCARKO testis volume after DHT treatment indicates that DHT is having an effect on another cell type that may be either the PTMs or the Leydig cells. In addition, longer-term direct androgenic stimulation of spermatogenesis through the PTMs, without direct effects on the Sertoli cells, cannot be excluded. The 7-d time course was chosen for studies reported here because longer periods of androgen treatment will induce testicular descent in hpg and hpg.SCARKO mice, which, in itself, will affect germ cell development.

A previous study reported that T and DHT have similar effects on the development of spermatogenesis in the hpg mouse over an 8-wk time period (26). Our results largely confirm this report, although DHT was less effective than T for the induction of round spermatid formation, which may be due to the relatively short duration of the current study with attendant lack of testicular descent. Unexpectedly, however, we observed marked differences in the effects of T and DHT on spermatogenesis in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice. These differences appear to be due to the induction of FSH release from the pituitary by T but not DHT. In normal adult males, androgens act to decrease circulating FSH primarily through effects on hypothalamic GnRH. In the hpg mouse, however, the primary effect of exogenous steroids is likely to be at the pituitary, and there is evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies that T can stimulate pituitary FSH and Fshb levels (29,30,31,32). More pertinently, so far as this study is concerned, it has also been shown that estrogen will increase circulating FSH levels in male hpg mice (33,34). The differential induction of FSH levels by T, but not by DHT, makes it highly likely that in our hpg models aromatization of T to estrogen leads to stimulation of pituitary FSH release. Differences between the effects of T and DHT on spermatogenesis in hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice can be attributed therefore to the effects of FSH, which has been shown to stimulate spermatogenesis in both hpg.SCARKO and hpg.ARKO mice (6).

In summary, nonaromatizable androgen does not stimulate spermatogenesis in hpg mice lacking ARs on the Sertoli cells. Androgen stimulation of spermatogenesis therefore requires direct androgen action on the Sertoli cells.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online March 12, 2010

Abbreviations: AR, Androgen receptor; ARKO, lacking AR genomic manipulation; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; hpg, hypogonadal; PTM, peritubular myoid cell; PTM-ARKO, lacking ARs in the PTM; SCARKO, lacking ARs only in the Sertoli cells; T, testosterone; Tfm, lacking AR through a natural mutation.

References

- Lyon MF, Hawkes SG 1970 X-linked gene for testicular feminization in the mouse. Nature 227:1217–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gendt K, Swinnen JV, Saunders PT, Schoonjans L, Dewerchin M, Devos A, Tan K, Atanassova N, Claessens F, Lécureuil C, Heyns W, Carmeliet P, Guillou F, Sharpe RM, Verhoeven G 2004 A Sertoli cell-selective knockout of the androgen receptor causes spermatogenic arrest in meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:1327–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel MH, Wootton AN, Wilkins V, Huhtaniemi I, Knight PG, Charlton HM 2000 The effect of a null mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor gene on mouse reproduction. Endocrinology 141:1795–1803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Wang Y, Lu N, Matzuk MM 1997 Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet 15:201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy H, Danilovich N, Morales CR, Sairam MR 2000 Qualitative and quantitative decline in spermatogenesis of the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor knockout (FORKO) mouse. Biol Reprod 62:1146–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Monteiro A, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Abel MH 2010 Effect of FSH on testicular morphology and spermatogenesis in gonadotrophin-deficient hypogonadal (hpg) mice lacking androgen receptors. Reproduction 139:177–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C, Chen YT, Yeh SD, Xu Q, Wang RS, Guillou F, Lardy H, Yeh S 2004 Infertility with defective spermatogenesis and hypotestosteronemia in male mice lacking the androgen receptor in Sertoli cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:6876–6881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdcraft RW, Braun RE 2004 Androgen receptor function is required in Sertoli cells for the terminal differentiation of haploid spermatids. Development 131:459–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh M, Saunders PT, Atanassova N, Sharpe RM, Smith LB 2009 Androgen action via testicular peritubular myoid cells is essential for male fertility. FASEB J 23:4218–4230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattanach BM, Iddon CA, Charlton HM, Chiappa SA, Fink G 1977 Gonadtrophin releasing hormone deficiency in a mutant mouse with hypogonadism. Nature 269:338–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott IS, Charlton HM, Cox BS, Grocock CA, Sheffield JW, O'Shaughnessy PJ 1990 Effect of LH injections on testicular steroidogenesis, cholesterol side-chain cleavage P450 messenger RNA content and Leydig cell morphology in hypogonadal mice. J Endocrinol 125:131–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lécureuil C, Fontaine I, Crepieux P, Guillou F 2002 Sertoli and granulosa cell-specific Cre recombinase activity in transgenic mice. Genesis 33:114–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Monteiro A, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Abel MH 2009 Occurrence of testicular microlithiasis in androgen insensitive hypogonadal mice. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7:88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steenbrugge GJ, Groen M, de Jong FH, Schroeder FH 1984 The use of steroid-containing Silastic implants in male nude mice: plasma hormone levels and the effect of implantation on the weights of the ventral prostate and seminal vesicles. Prostate 5:639–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew TM 1992 A review of recent advances in stereology for quantifying neural structure. J Neurocytol 21:313–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wreford NG 1995 Theory and practice of stereological techniques applied to the estimation of cell number and nuclear volume of the testis. Microsc Res Tech 32:423–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell LD, Ettlin RA, Sinha Hikim AP, Clegg ED 1990 Histological and histopathological evaluation of the testis. Clearwater, FL: Cache River Press; 119–161 [Google Scholar]

- Baker PJ, O'Shaughnessy PJ 2001 Role of gonadotrophins in regulating numbers of Leydig and Sertoli cells during fetal and postnatal development in mice. Reproduction 122:227–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez M, Spaliviero JA, Grootenhuis AJ, Verhagen J, Allan CM, Handelsman DJ 2005 Validation of an ultrasensitive and specific immunofluorometric assay for mouse follicle-stimulating hormone. Biol Reprod 72:78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe RM 2005 Sertoli cell endocrinology and signal transduction: androgen regulation. In: Skinner MK, Griswold MD, eds. Sertoli cell biology. London: Elsevier; 199–216 [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DF, Muffly KE, Nazian SJ 1993 Reduced testosterone during puberty results in a midspermiogenic lesion. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 202:457–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell L, McLachlan RI, Wreford NG, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM 1996 Testosterone withdrawal promotes stage-specific detachment of round spermatids from the rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod 55:895–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P, Robson M, Spaliviero J, McTavish KJ, Jimenez M, Zajac JD, Handelsman DJ, Allan CM 2009 Sertoli cell androgen receptor DNA binding domain is essential for the completion of spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 150:4755–4765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Nie R, Prins GS, Saunders PT, Katzenellenbogen BS, Hess RA 2002 Localization of androgen and estrogen receptors in adult male mouse reproductive tract. J Androl 23:870–881 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston DS, Russell LD, Friel PJ, Griswold MD 2001 Murine germ cells do not require functional androgen receptors to complete spermatogenesis following spermatogonial stem cell transplantation. Endocrinology 142:2405–2408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, O'Neill C, Handelsman DJ 1995 Induction of spermatogenesis by androgens in gonadotropin-deficient (Hpg) Mice. Endocrinology 136:5311–5321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy PJ, Sheffield JW 1990 Effect of testosterone on testicular steroidogenesis in the hypogonadal (hpg) mouse. J Steroid Biochem 35:729–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel MH, Baker PJ, Charlton HM, Monteiro A, Verhoeven G, De Gendt K, Guillou F, O'Shaughnessy PJ 2008 Spermatogenesis and Sertoli cell activity in mice lacking Sertoli cell receptors for follicle-stimulating hormone and androgen. Endocrinology 149:3279–3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea MA, Weinbauer GF, Marshall GR, Nieschlag E 1986 Testosterone stimulates pituitary and serum FSH in GnRH antagonist-suppressed rats. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 113:487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea MA, Marshall GR, Weinbauer GF, Nieschlag E 1986 Testosterone maintains pituitary and serum FSH and spermatogenesis in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist-suppressed rats. J Endocrinol 108:101–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin S, Fielder TJ, Swerdloff RS 1987 Testosterone selectively increases serum follicle-stimulating hormonal (FSH) but not luteinizing hormone (LH) in gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist-treated male rats: evidence for differential regulation of LH and FSH secretion. Biol Reprod 37:55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spady TJ, Shayya R, Thackray VG, Ehrensberger L, Bailey JS, Mellon PL 2004 Androgen regulates follicle-stimulating hormone β gene expression in an activin-dependent manner in immortalized gonadotropes. Mol Endocrinol 18:925–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebling FJ, Brooks AN, Cronin AS, Ford H, Kerr JB 2000 Estrogenic induction of spermatogenesis in the hypogonadal mouse. Endocrinology 141:2861–2869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P, Allan CM, Notini AJ, Axell AM, Spaliviero J, Jimenez M, Davey R, McManus J, MacLean HE, Zajac JD, Handelsman DJ 2008 Oestradiol-induced spermatogenesis requires a functional androgen receptor. Reprod Fertil Dev 20:861–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]