Abstract

Understanding the effects of ionising radiations are key to determining their optimal use in therapy and assessing risks from exposure. The development of microbeams where radiations can be delivered in a highly temporal and spatially constrained manner has been a major advance. Several different types of radiation microbeams have been developed using X-rays, charged particles and electrons. For charged particles, beams can be targeted with sub-micron accuracy into biological samples and the lowest possible dose of a single particle track can be delivered with high reproducibility. Microbeams have provided powerful tools for understanding the kinetics of DNA damage and formation under conditions of physiological relevance and have significant advantages over other approaches for producing localised DNA damage, such as variable wavelength laser beam approaches. Recent studies have extended their use to probing for radiosensitive sites outside the cell nucleus, and testing for mechanisms underpinning bystander responses where irradiated and non-irradiated cells communicate with each other. Ongoing developments include the ability to locally target regions of 3-D tissue models and ultimately to target localised regions in vivo. With future advances in radiation delivery and imaging microbeams will continue to be applied in a range of biological studies.

Keywords: Microbeams, Ionizing radiation, DNA repair, Bystander effects, Tissue models

1. Background

Rapid advances in our understanding of radiation responses, at the subcellular, cellular, tissue and whole body levels have been driven by the advent of new technological approaches for radiation delivery. Ionising radiation microbeams allow precise doses of radiation to be delivered with high spatial accuracy. They have evolved through recent advances in imaging, software and beam delivery to be used in a range of experimental studies probing spatial, temporal and low dose aspects of radiation response. A range of microbeams have been developed worldwide which include ones capable of delivering charged particles, X-rays and electrons. Localised delivery of radiation at the subcellular level is proving a powerful tool. For example, localized production of radiation-induced damage in the nucleus allows probing of the key mechanisms of DNA damage sensing, signalling and repair. Crucially this can be done under conditions where cells retain viability and where the responses to relevant environmental, occupational or clinical doses can be tested. These approaches have started to unravel some of the early events which occur after localised DNA damage within cells. The ability to target radiation with microbeams at subcellular targets has been used to address fundamental questions related to radiosensitive sites within cells. Recent studies have shown an important role for mitochondria as potential direct targets of radiation exposure leading to reactive oxygen species mediated responses. A current development has been the move from studies with 2-D cell culture models to more complex 3-D systems where the possibilities of utilizing the unique characteristics of microbeams in terms of their spatial and temporal delivery will make a major impact.

This review will consist of the following sections:

Introduction to microbeams and their uses

Current radiation microbeams

Probes of DNA damage and repair

Comparison with other targeted damage approaches

Subcellular targeting and studies in tissues

Future perspectives

2. Introduction to microbeams and their uses

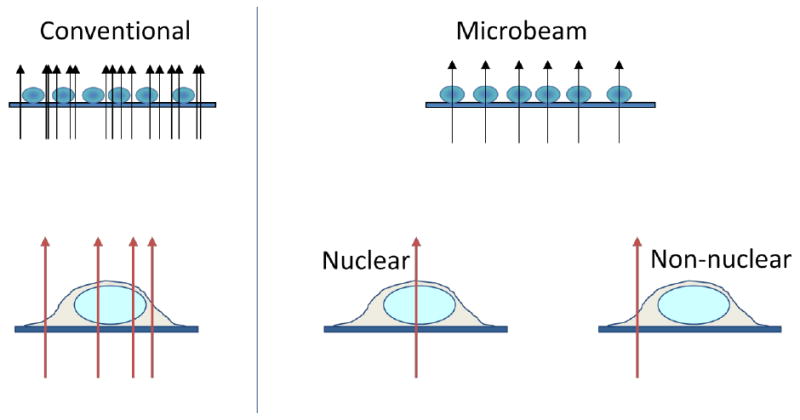

Recent technological advances and new challenges in radiation biology are behind a renewed interest in the use of microirradiation techniques for biological studies. Despite the advantages of deterministic irradiation achieved by targeting and analyzing cells individually having been recognized since the early 1950s [1], technology for developing sophisticated microirradiation facilities only became available in the late 1990s. Modern radiobiological microbeams are facilities able to deliver precise doses of radiation to preselected individual cells (or part of them) in vitro and assess their biological consequences on a single cell basis (Figure 1). They are therefore uniquely powerful tools for addressing specific problems where very precise targeting accuracy and dose delivery are required.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the advantages of microbeam irradiation compared to conventional broad field exposures. The ability to deliver uniform numbers of radiation tracks to each cell in a population and to determine where these interact is depicted

The main rational for the development of modern microbeams comes from the necessity to evaluate the biological effects of very low doses of radiation (down to exactly one particle traversal) in order to evaluate environmental and occupational radiation risks, where only a few cells in the human body are affected [2] separated by intervals of months or years. Due to the uncertainties of conventional irradiations and random Poisson distribution of tracks, such scenarios cannot be simulated in vitro using conventional broad field techniques. Current excess cancer risks associated with exposure to very low doses of ionizing radiation are therefore estimated by extrapolating high dose data obtained from in vitro experiments or from epidemiological data from the atomic bomb survivors. This approach, however, suffers from limited statistical power and is unable to resolve uncertainties from confounding factors forcing the adoption of the precautionary linear non-threshold (LNT) model. Moreover, there is experimental evidence of non-linear effects at low doses. Genomic instability [3], hypersensitivity [4] and bystander effect [5,6], for example, may increase the initial radiation risk, while the adaptive response [7] may act as a protective mechanism reducing the overall risks at low doses. Microbeams allow accurate targeting of single cells and analysis of the induced damage on a cell-by-cell basis which is critical to assess the shape of the dose-response curve in the low dose region. Using microbeams, it has been possible to determine the effect of single particle traversals for oncogenic transformation [8], micronuclei formation [9] and genetic instability [10]. Similarly, they have been successfully used to investigate with great accuracy low dose phenomena such as low dose hypersensitivity [11] and bystander effects [12], [13] and are currently used to delineate low dose risks in cells and tissues.

A recently growing area of interest for the use of microbeams is in probing the spatial and temporal evolution of radiation damage. It is widely accepted that the biological effectiveness of ionizing radiation is determined by the ionization pattern (i.e. track structure) produced inside cells or tissues [14]. Understanding the extent and pattern of DNA damage induced [15], [16] and their spatio-temporal evolution is therefore of critical importance for assessing biological risks of radiation exposure. Double stand breaks (DSBs) are considered the most critical DNA lesion induced by radiation due to the complexity of cellular mechanisms involved in the correct rejoining of physically separated DNA sections. The DNA damage caused by a charged particle traversal is the result of a complex clustering of ionizations which occurs along the particle path itself (core) and radially due to secondary electrons (penumbra). Track structures simulations [17] and experimental measurements performed in nanodosimetry detectors such as the Jet Chamber [18] and live cells [19] have determined how the spatial distribution of ionization critically depends on the mass and energy of the particle. As a consequence, charged particle beams are expected to induce clusters of DNA breaks which result in the formation of complex DNA-dsbs. Despite the final end point being the physical separation of the DNA double helix, DNA-dsbs arising from cluster of DNA lesions present a more difficult challenge for the cell repair mechanisms. Nikjoo and colleagues [20] calculated that although the number of breaks per unit dose remains nearly constant with the LET, their complexity varies significantly. Whilst for low energy electrons only 20-30% of DNA-dsbs can be considered complex, this proportion increases to 70% for high LET α-particles and to 90% when base damages are included. In general, the complexity of the DNA breaks is rapidly enhanced with increasing the LET.

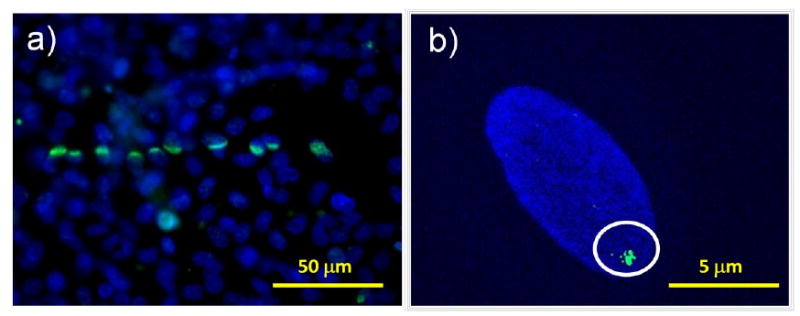

Crucially, DSBs resulting from multiple damage sites are often associated with loss of genetic material and high probability of incorrect rejoining which are responsible for late effects such as chromosomal aberrations and genetic mutations including carcinogenesis. Despite their clearly fundamental role in determining the fate of the irradiated cell, little is known about the spatio-temporal evolution of DSBs and their related repair events. There are currently two main aspects of great interest of the spatio-temporal evolution of DSBs: the first is related to breaks mobility within the cell nucleus while the second concerns the dynamic interaction and alternation of DNA repair proteins. Theoretical attempts to describe how ends from different DBSs meet to form chromosome aberrations have led to two conflicting theories. While the “contact first” theory proposes that interactions between chromosome breaks can only take place when DSBs are created in chromatin fibres that co-localize, the “breakage first” theory is based on DSBs moving over large distances before interacting. Extensive DSB migration and interaction is therefore the centre of open debates [21], [22]. Using microbeams, it is possible to induce DSBs in precise locations inside the cell nucleus (recent biological developments allow staining of chromosome domains in live cells [23]) at precise times and investigate their spatiotemporal evolution (see figure 2). Being able to control the site and time of the damage induction allows investigations of the DSB mobility using conventional immunofluorescence techniques. Correlating this data to the extent of the effect induced can then provide critical information on how DSBs mobility affects DNA repair and subsequential cellular response.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the key aspects of a microbeam facility.

Localised DNA damage induced by a soft X-ray microbeam. Primary human fibroblasts where a line of radiation is placed across a confluent monolayer (panel a) or a single location on a single cell irradiated (panel b). Cells were stained for γH2AX 10 minutes after exposure and counterstained with DAPI.

On the other hand a deeper understanding of the sequential steps followed by the DNA repair proteins in time is needed to further understand this fundamental cell mechanism. The dynamic interaction and exchanges of DNA repair proteins at the site of damage is a critical aspect as it provides clues of the necessaries steps, functionality and requirements of the different enzymatic activities involved in the repair process. The current knowledge of repair/missrepair events that follow DSBs induction by ionizing radiation relies on immunofluorescence assays (i.e. γ-H2AX or other damage response proteins) on fixed cells [19], [24] [25]. Despite some contradictory indications of chromatin movement and subsequential formation of repair clusters [22], [24], these data provide only a static view of a selected point in time from which is very difficult to draw dynamic conclusions. Studies looking at the dynamics of DNA repair recruitment are currently being attempted [25], [26] using high atomic number charged particle irradiations (which form highly clustered ionizations) and high resolution microscopy. Modern microbeams are also equipped with state of the art imaging stations in order to accurately monitor the cell response to specific radiation insults. Moreover, the high precision in the delivery of radiation damage to sub-cellular sites using a wide range of LET radiations (from X-rays to heavy ions) and the single cell nature of the experiments represent a natural approach to follow cellular reactions to radiation insults in time. Using microbeam approaches, the spatio-temporal details of the irradiation of each sample within a population can be precisely controlled and the cellular response assessed on a cell by cell basis. Combined with the use of GFP-tagged proteins, these features make radiation microbeams a unique tool for the analysis of the spatio-temporal evolution of the DSBs repair processes.

3. Current radiation microbeams

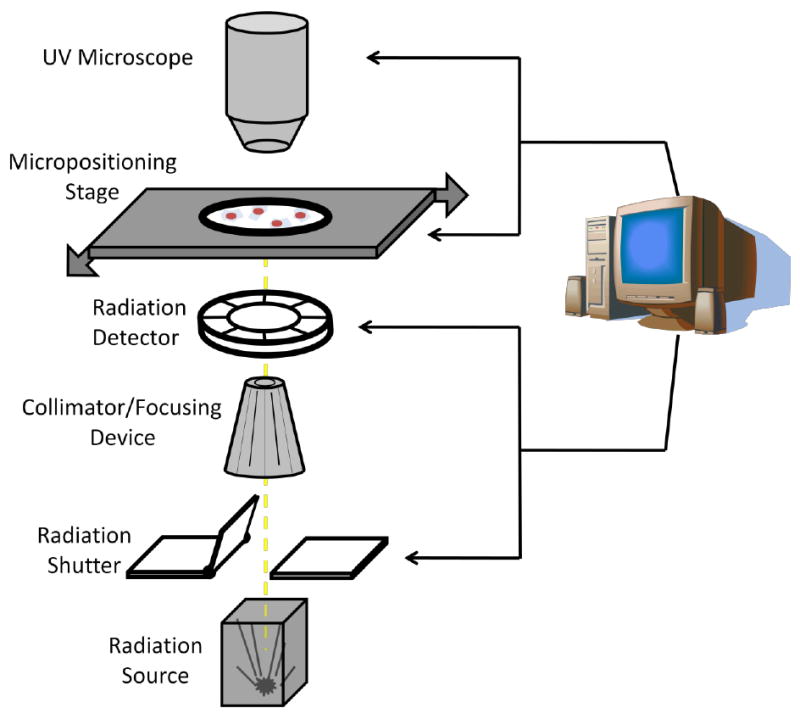

The majority of radiobiological microbeams are centred on particle accelerators in order to irradiated biological samples with an exact number of ions however X-ray and electron microbeams have also been developed and are routinely used. Many different experimental set-ups have been exploited in order to achieve a precise dose delivery to individual preselected cells (or part of them). In general, however, there are a few basic requirements that a microbeam facility has to fulfil in order to perform accurate radiobiological experiments (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the key components of a radiation microbeam.

These are:

Production of a stable radiation beam of micron or submicron size.

Radiation detectors able to monitor, with high efficiency, the dose delivered to the samples and trigger the beam stop mechanism when the desired dose has been reached.

Image system for sample localization. This will have to be supported by appropriate software for image analysis and co-ordinate recording.

Micropositioning stage to align the samples with the radiation probe with high spatial resolution and reproducibility. The stage speed is also critical in assuring the high throughput necessary to investigate low frequency events (i.e. oncogenic transformation).

3.1. Charged particle microbeams

Charged particle microbeams can be grouped into two main categories according to the approach used to reduce the radiation beam to sub-cellular dimensions. While collimation approaches were the preferred choice of the first radiobiological microbeams, electromagnetic focusing is currently the most popular approach reflecting both technological advances and the need for finer resolutions. The collimation approach is centred on the use of pinholes or collimators to physically obstruct the radiation beam allowing particles to emerge only through a narrow aperture. The advantages offered by the collimation approach include a relatively straightforward alignment and beam location, easy extraction into air (necessary for live cell irradiation) and reduction of particle flux to radiobiological relevant dose-rate ranges. On the other hand, particle scattering (which allows low energy particles to emerge with a wider lateral angle than the primary beam) represents a strong limitation to the final beam size and targeting accuracy. Collimators and set of apertures have been extensively used at the Gray Cancer Institute and Columbia University, pioneers of modern radiobiological microbeams. Using fused silica tubing with apertures as small as 1 μm in diameter, 90% protons and 99% of 3He2+ ions were confined within a 2 μm spot [27] while using laser-drilled micro apertures (5 and 6 μm) a 5 μm beam with 91% of unscattered particles was achieved [28]. Collimation methods are still successfully used at JAERI (Takasaki, Japan) [29] and the INFN-LNL (Italy) [30].

The focusing approach has rapidly increased in popularity mainly driven by the availability of existing facilities (previously used for nuclear microscopy) and the need to investigate the sensitivity of sub-cellular targets. Using a variety of electromagnetic quadrupole doublets [31,32], extremely narrow charged particle beams (down to a few 10s of nanometers) can be achieved in vacuum. Moreover existing nuclear microscopy microbeams can access a large range of ions and energies ranging from He to Au and U and LETs values up to 15000 keV/μm [33]. However, as the focused beam has to be extracted in air, significant scattering is introduced by the vacuum window, air gap and traversal of the cell support membrane. Focused spots of 1 μm or less on the samples are however achievable with a very low fraction of particles reaching the targets being scattered. Successful charged particle microbeams based on focus systems have been developed and are routinely used in Germany at the PTB [34], the GSI [35], the University of Munich [31] and Leipzig,[36], in Japan at the NIRS [37] and at Columbia University (USA) [32].

Another key feature of the modern microbeam facilities is the ability to deliver a precise number of particles. This requires a high efficiency detection system (which will trigger the signal when the pre-set number of events has been reached) coupled to a very fast beam shuttering system. Particle detection is probably the feature that differs most between microbeam facilities developed so far. They basically divide into two categories according to whether the detection occurs before or after the particles reach the biological sample. By placing the detector between the vacuum window and the samples, no further constraints are imposed on the sample holder or the cell environment while the inevitable detector-beam interaction reduces the quality and accuracy of the exposure. In order to minimize energy loss in the detector, only thin, transmission type detectors are appropriate. These detectors are generally thin films of plastic scintillators whose light flashes generated by the particles traversal are collected by a photomultiplier and then processed [38]. The alternative configuration consists of placing the detector behind the sample holder. Using this approach, no extra scattering is introduced by the detector and better targeting accuracy can in theory be reached. While conventional solid state detectors can be used [39], such configuration requires that the delivered particles have enough energy to pass through the samples setting a limit of the lowest energy usable. In many cases, it is also necessary to remove the culture medium requiring additional procedures (such as humidity control devices) to keep the cells viable during the irradiation process.

3. Electron and X-ray microbeams

X-ray and electron microbeams have also been developed in order to provide quantitative and mechanistic radiobiological information that complement the charged particle studies. As photons do not suffer from scattering problems, X-ray microbeams are in theory capable of achieving radiation spots in air of an order of magnitude or smaller than those so far achieved with ion beams. Moreover, such high spatial resolution is maintained as the X-ray beam penetrates through cells making it possible to irradiate with micron and sub-micron precision, targets that are several tenths or hundreds of microns deep inside the samples. Current X-ray microbeams employ benchtop based electron bombardment X-ray sources [40] for energies up to a few keV or synchrotrons [41] for X-ray beams of a few 10s of keV. The X-ray focusing is generally achieved using diffraction gratings (Zone Plates) which are commonly used in X-ray microscopy to produce X-ray spots down to 50nm. Reflecting X-ray optics are also used [41] and current development [42] promise to significantly improve both spot size and dose rate.

As for X-ray, electron microbeams are generally self contained units with relatively low development and maintenance costs. They rely on standard electron guns and electrostatic devices to produce and accelerate energetic electron beams which are subsequently reduced to micrometer size by the use of apertures or electromagnetic focusing [43]. As electrons greatly scatter as they interact with biological samples, it is impossible for electron microbeams to achieve targeting resolutions at the micron or submicron level despite the actual size of the focused beam. However, the great advantage of electron (and X-ray) microbeams concerns the ability to easily vary the energy (and therefore the LET) in order to investigate the relative biological importance of various parts of the electron track. In this respect, electron and X-ray microbeams complement the work done with charged particle facilities to investigate the LET dependence.

Finally, the interest in using 3D biological samples and following the dynamics of the DNA damage formation/repair have highlighted the need to equip microbeam facilities with enhanced image stations. Multiphoton fluorescence microscopy is an imaging technique that allows imaging of living tissue samples up to a few millimeters thick using lasers to produce the desired excitation only at a specific depth. As a consequence, the insult induced by multiphoton imaging is considerably lower and high resolution images at depth of several hundred microns can be obtained. Moreover, the use of tunable lasers allows multiphoton microscopes to follow with great precision post-irradiation cellular dynamics by acquiring time-lapse images [32].

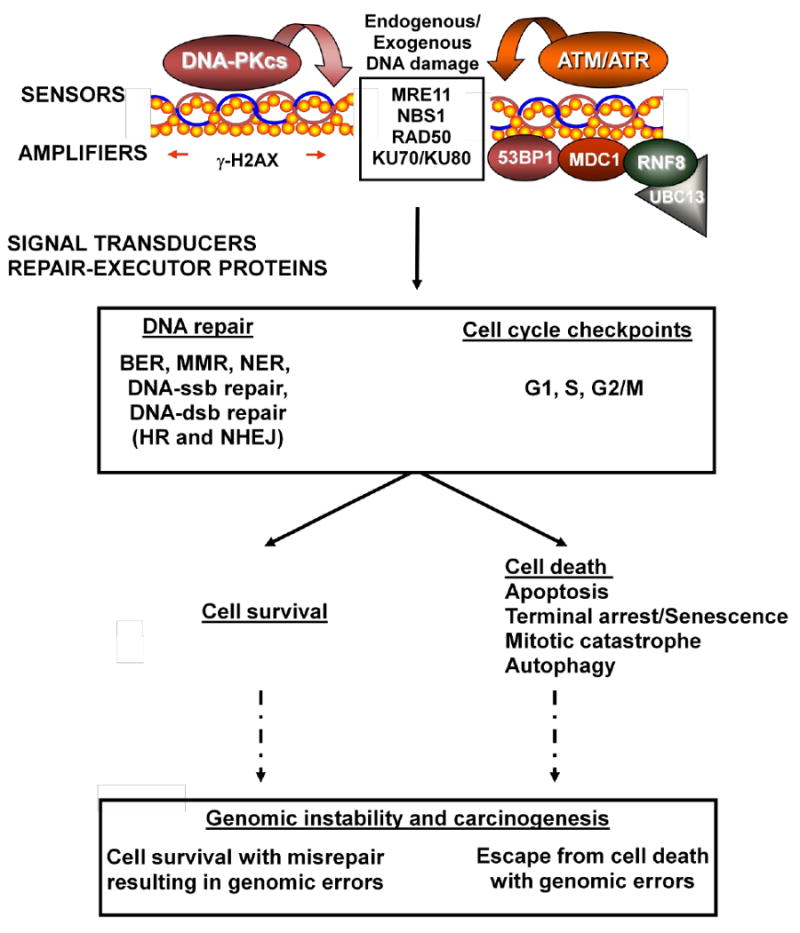

4. Probes of DNA damage and repair

The development of microbeams has allowed further dissection of cellular and molecular events involved in various types of DNA damage and repair. However, as previously mentioned, chromosomal and lesion mobility within the nucleus and the dynamic interaction between chromosomal and DNA repair proteins remain unclear and require further investigation. In addition to understanding the processes of DNA damage detection and repair within the cell, these studies have allowed the development of potential clinical and gene therapy targets that may be used for several syndromes and diseases, including hereditary disorders and cancers. Some of these developments have the potential as a single or combinatorial treatment together with current standard therapies. Together with the development of improved therapy, specialized probes to detect and monitor DNA damage induction and repair is critically important. Initial assays to detect DNA damage and repair utilized whole chromosomal analyses such the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and laser-induced fluorescence detection following capillary electrophoresis and single-cell analyses such as the COMET and COMET-FISH assays [44,45]. The TUNEL assay was another single-cell assay that was adapted from a nucleic acid end-labelling technique (i.e. used to detect apoptotic-associated DNA fragmentation), to detect DNA breaks by relying on the incorporation of halogenated nucleotides at sites of breaks which could be detected by specific antibodies against the halogenated-side groups. The latter method was used in conjunction with antibodies against DNA-dsb repair proteins, RAD50 and MRE11, as probes for DNA damage and repair in one of the first reports utilizing a soft X-ray microbeam and immunofluorescence microscopy analysis to observe accumulation of proteins at sub-nuclear sites of DNA damage [22]. Mammalian cells have developed many mechanisms to detect and repair DNA damage that constantly bombards the cells, from external and internal sources, including environmental carcinogens, replication errors and normal cellular metabolism. These specialized DNA repair pathways include nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER), mismatch repair (MMR), DNA single-strand break (DNA-ssb) repair and DNA double-strand break (DNA-dsb) repair pathways. These repair processes require sensor, amplifier, signal transducer and repair-executor proteins, which may be intimately- or transiently- associated with the chromosome and the cell cycle machinery throughout the cell cycle to maintain genomic stability (see Figure 4). Investigations to find probes include histone proteins which are stably-associated and chromatin-associated proteins (e.g. heterochromatin-proteins and cohesions) which are intimately associated within chromatin that act as sensors and amplifiers, transcription and cell cycle checkpoint proteins which may be transiently-associated within chromatin as global surveyors of genomic integrity and may act as sensors, amplifiers and/or transducers, and repair proteins which transiently associate with chromatin [46-48]. The development of specific antibodies to detect these proteins has proven invaluable and currently many of these are used as probes of DNA damage and repair in ummunofluorescence microscopy and immunohistochemistry analysis [49]. The histone variant, H2AX, which is phosphorylated at residue Ser139 (γ-H2AX) upon DNA dsb-induction, is the current gold standard probe. It is exquisitely responsive to DNA-dsbs and is observed to form foci at sites of damage within nuclei. Within the chromatin, γ-H2AX phosphorylation occurs over megabase domains surrounding a break site, making it a strong amplifier of the DNA damage signal [46]. γ-H2AX foci kinetics follows those of DNA-dsb rejoining kinetics and γ-H2AX foci can persist at sites of DNA damage following its repair. In addition to γ-H2AX, other histones have been identified as DNA damage probes (e.g. histone H1, H4) and other post-translational modifications of histones are additional indicators of the repair process (e.g. acetylation, methylation). Furthermore, high mobility group (HMG) proteins, structural maintenance of chromosome (SMC) proteins which are part of the cohesion complex, nuclear protein positive cofactor 4 (PC4), heterochromatin proteins (e.g. HP1) and polycomb group proteins (PHF-1) have also been shown to localize to DNA damage sites and these can be used as DNA damage probes [48,50-53].

Figure 4.

Cellular pathways to maintain genomic stability. Exogenous (ionizing radiation) or endogenous (reactive oxygen species) agents can induce various types of DNA damage. DNA damage sensors (e.g. MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN complex), ATM, ATR, DNA-PKcs-KU70-KU80 (DNA-PK complex)) localize and subsequently activate and recruit further factors that amplify the DNA damage signal (e.g. γ-H2AX) and initiate downstream signalling cascades including cell cycle checkpoint arrests and DNA repair processes. Ultimately, correct repair leads to cell survival or irreparable damage leads to cell death to eliminate the propagation of genomic errors and maintain genomic stability. However, in the presence of incorrect repair with cell survival or escape from cell death with genomic errors, accumulation of these errors can lead to genomic instability and carcinogenesis.

In addition to histones, DNA probes for various types of DNA lesions and repair have been developed: antibodies that detect various UV-photoproducts (e.g. pyrimidine-pyrimidone (6–4) photoproducts (6-4PPs), cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 8-oxoguanine (8-oxo)) and PCNA and the XP-associated proteins involved in NER, XRCC1 and FEN-1 in BER, MLH-associated proteins in MMR, PARP-1, RPA and hSSB1 proteins in DNA-ssb repair, and RAD50, MRE11, NBS1, KU70/80 heterodimer, DNA-PKcs, LigaseIV, XRCC4, ATM, WRN, BLM, RAD51-family and BRCA-family of proteins involved in the two main DNA-dsb repair pathways (i.e. homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ)) [54-59]. Furthermore, many of these proteins are also involved in multiple repair pathways, and this cross-talk increases the ability of the cell to maintain genomic stability [59-62].

Currently, the DNA-dsb repair proteins, MRE11 and KU70/80 heterodimer are thought to be the earliest sensors of DNA-dsbs [59,63]. The MRN complex (consisting of the MRE11, RAD50 and NBS1 DNA-dsb repair proteins) is thought to sense DNA-dsbs and recruit the ATM kinase to these sites, which facilitates the early activation (auto-phosphorylation of ATM at residue Ser1981) and subsequent downstream ATM signaling [59]. The Ku70/80 heterodimer, on the other hand, recruits the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PKcs) to DNA ends, which results in its activation and auto-phosphorylation at threonine 2609, to initiate NHEJ-mediated DNA-dsb repair. The Ku70/80 heterodimer has also been shown to modulate the ATM-dependent response to DNA-dsbs [64]. The collaboration between ATM and DNA-PK also extends from expression to activation, where while ATM has been shown to be important for the phosphorylation and full activation of DNA-PKcs and NHEJ-mediated DNA-dsb repair [65]; reciprocally, DNA-PKcs activity has been shown to be important for ATM expression [66]. The ATM, ATR and DNA-PK kinases all redundantly phosphorylate γ-H2AX. These phosphorylations recruit MDC1 (mediator of checkpoint-1), which then acts to amplify the DNA damage signal by recruiting other signal transducer proteins such as RNF8-UBC13, an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, and 53BP1, p53-binding protein 1. Furthermore, ATM phosphorylates the checkpoint protein, CHK2, at its Thr68 residue, and the tumour suppressor protein, p53, within the chromatin, which are then released to act as signal transducers of DNA damage and to initiate cell cycle checkpoint arrest or, in response to irreversible DNA damage, cell death.

Studies have confirmed in patient biopsies and tissue samples, that some of these probes are important indicators of DNA damage, absence of repair or misrepair and genomic instability. For example, a correlation of staining pattern has been observed with nuclear staining of γ-H2AX, activated ATMSer1981, Chk2Thr68 and p53Ser15: lower levels found within pre-malignant tissue and increased levels within increasingly malignant tumour tissue [67,68]. Furthermore, skin biopsies are also currently being tested to determine if these DNA damage and repair probes can be utilized for detection of exposures to low dose radiation or pre-screening of patients for radiotherapy and other forms of clinical therapy that induces DNA damage [49,69,70].

Finally, in addition to chromosome-associated, repair and checkpoint proteins, recent studies have also shown that cellular stress response proteins, such as PML nuclear bodies and heat shock proteins (e.g. HSP70 and HSP90) may be used as indicators of and sensitizers to DNA damage and repair [71-73]. Further investigation will confirm whether these can be definitively used as DNA damage and repair probes.

5. Comparison with other targeted damage approaches

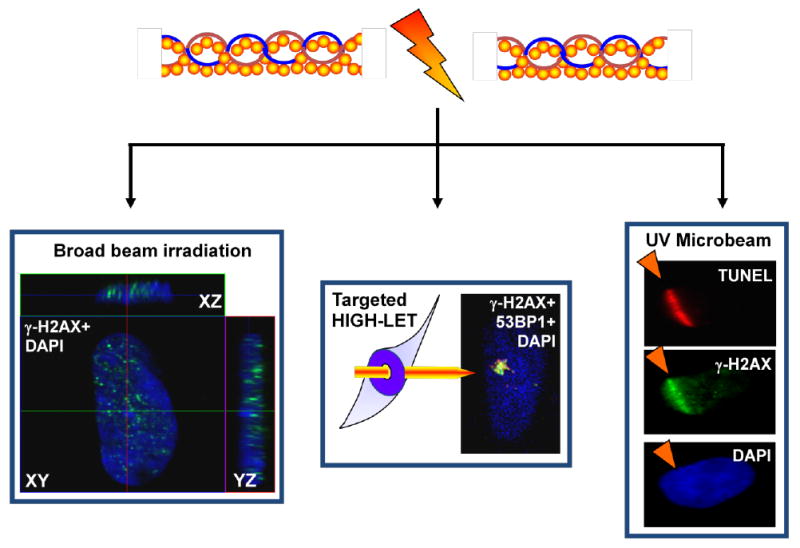

Most of the DNA damage and repair pathways that are analysed based on X-ray and electron microbeams are of complex and DNA-dsb repair pathways, as DNA-dsbs are considered to be the most critical lesion leading to the cellular responses and death that is observed (e.g. correlation with cell survival, chromosomal aberrations and carcinogenesis). A novel method was then introduced by Limoli and Ward [74] to induce DNA-ssbs and -dsbs using ultraviolet (UV) irradiation in combination with DNA containing incorporated halogenated nucleotide analogues and intercalators (e.g. Hoechst 33258). This sparked laser microirradiation methods including those by Rogakou and colleagues who first showed γ-H2AX foci accumulation within nuclei similar to foci formed in response to X-ray irradiation [75] (see figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sub-nuclear targeting methods to detect and track DNA damage signalling and repair complexes in situ. All three images are of fixed nuclei from immunofluorescence microscopy analyses following exposure to broad beam γ-irradiation (i.e. 137Cs-source), high-LET (i.e. Helium-3 ion) targeted microbeam irradiation and UV+Hoechst-laser microirradiation, left to right, respectively. Fixed cell immunofluorescence microscopy analyses have been invaluable in obtaining qualitative and quantitative morphological, sub-nuclear distribution and kinetics of DNA sensor and repair proteins. By combining sub-nuclear targeting techniques with live cell imaging of fluorescently-tagged DNA sensor and repair proteins, for example through FLIM and FRAP analyses, these have allowed the determination of protein-chromatin mobility, and further sensitive and specific observations of the temporal and spatial distributions of DNA sensor and repair proteins (see text).

X-ray and electron microbeams have a higher energy spectrum and induce DNA damage through ionizations and generation of reactive oxygen species to create a range of DNA lesions (i.e. inter- and intra-strand cross-links, base damage, ssbs and dsbs) including sites with complex lesions (i.e. local sites containing a combination of lesions). UV laser microirradiations have a lower energy spectrum. Alone, UV-A (>330nm) and UV-C (∼254nm) wavelengths of laser microirradiation induce a different spectrum of DNA damage, including various UV-photoproducts (e.g. pyrimidine-pyrimidone (6–4) photoproducts (6-4PPs), cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 8-oxoguanine (8-oxo)), which have greatly assisted the dissection of NER pathways [58].

In addition to the UV-A and UV-C spectrum, laser microirradiation has been used beyond these wavelengths ranging into the near infra-red region to induce sub-nuclear damage [53,76,77]. However, the characteristics and complexity of the lesions created by the different laser systems have not been clearly determined. In the past three years, several groups have attempted to directly compare the quality of DNA lesions and DNA repair induced by X-ray and high LET microbeams with these UV laser microirradiation methods including comparing the induction of DNA-dsbs by using UV lasers alone and in combination with DNA containing incorporated halogenated nucleotide analogues and intercalators [59,78-81]. This is a critical area of microirradiation studies because the cellular damage and repair responses and pathways obtained from them depends on the types of lesions that are generated and the accuracy of determining these lesions. In comparing 337nm UV-A laser irradiation with and without DNA containing incorporated halogenated nucleotide analogues, different pulses of 532nm laser irradiation, and femtosecond 800nm laser irradiation, it has been found that the type of DNA damage and repair induced is greatly dependant on the wavelength and duration of the laser pulses which subsequently affects the DNA damage and repair factors that are recruited [79-81]. The ratio of base damage, cross-links, UV-photoproducts, DNA-ssbs, and DNA-dsbs varied greatly and only under certain conditions were compared to X-ray irradiation-induced DNA damage [59,81]. Many studies have used these methods, indicating that mostly DNA-dsbs were being induced [77]. Therefore, accurate and precise steps to confirm the types and complexity of DNA lesions that are induced are required when using these laser systems [76,77,82].

In combination with these sub-nuclear targeting microirradiation systems and immunofluorecence microscopy analyses, further developments in live cell imaging using fluorescently-tagged proteins and chromatin-immunoprecipitation techniques have enabled highly specific temporal mobility and kinetics, and spatial determinations of DNA damage sensor, signalling and repair proteins [48,51,61,83-87]. For example, the low diffusion mobility of H2AX following DNA damage induction was determined using FRAP and confirmed that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of H2AX occurred within the sites of breaks as opposed to the recruitment and release of H2AX from other nuclear regions [88]. Both fluorescence life-time imaging (FLIM) and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)_analyses revealed that chromatin immobilization at sites of DNA damage and release of DNA-PKcs is dependent on its phosphorylation status and affected by the expression of HMGA2 proteins [51,86]. By using chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP), the distribution of γ-H2AX, ATM and NBS1 proteins at and around the site of DNA breaks were analysed: in comparison to γ-H2AX phosphorylations which occur mostly beyond 2kb from the site of a DNA break, ATM and NBS1 proteins can be found directly at and within 2kb of the DNA break [87].

In addition to comparing the different laser microirradiation systems and mechanisms of DNA damage generation, Kong and colleagues also outlined the generation of thermal effects in these systems [80]. While Gragaravicius and colleagues found comparable levels and types of damage generated by the UV-laser microirradiation in combination with DNA intercalator and X-ray whole beam irradiation, it was suggested that this was due to the difference in focussed deposition of energy. Therefore, it compels the question, what are thermal effects in the X-ray and electron microbeam irradiation systems compared to the laser microirradiation systems, would there be differences in its non-targeted effects, and would these allow for further development of the latter in having a higher therapeutic index (reduced normal tissue with increased target tissue effects) and current clinical settings.

6. Subcellular targeting and studies in tissue

Although radiation microbeams are playing an important role in studies of DNA damage and repair, a major advantage is the ability to target different regions within cells and tissues. This has been utilised by several groups interested in responses to low dose targeted irradiation. The standard paradigm for radiation effects has been based on direct energy deposition in nuclear DNA driving biological response [5]. Previous studies using radioisotope incorporation have shown that the DNA within the nucleus is a key target as 131I-conconavalin A bound to cell membranes was very inefficient at cell killing, in contrast to 131I-UdR incorporated into the nucleus [89]. These authors also found that dose delivered to the nucleus, rather than cytoplasm or membranes, determined the level of cell death. Recently it has been shown that irradiation of cytoplasm alone can induce an effect. Wu et al. [90] found increased levels of mutations in AL cells after cytoplasmic irradiation using an α-particle microbeam. The types of mutations were similar to those that occurred spontaneously in unirradiated cells and were formed as a consequence of increased ROS species. Using a charged particle microbeam, it has been shown that bystander responses are induced in radioresistant glioma cells even when only the cell cytoplasm is irradiated, proving that direct damage to cellular DNA by radiation is not required to trigger the effect [91]. Under conditions of cytoplasmic-induced bystander signalling, disruption of membrane rafts also inhibits the response [91]. More recently several groups have reported an involvement of mitochondria in the signalling pathways involved in both cytoplasmically irradiated and bystander cells [92-94]. This is an expanding area of research which is beginning to understand subcellular radiosensitivity.

Several groups have now extended studies from cell-culture models to more complex tissue models and in vivo systems. These are providing convincing evidence for a role for bystander responses of relevance to the in vivo situation. The original work done in this area used human and porcine ureter models. The ureter is highly organised with 4-5 layers of urothelium, extending from the fully differentiated uroepithelial cells at the lumen to the basal cells adjacent to the lamina propria or supporting tissue. Using a charged particle microbeam, it was possible to locally irradiate a single small section of ureter such that only 4 – 8 urothelial cells were targeted. The tissue was then cultured to allow an explant outgrowth of urothelial cells to form. When micronucleated or apoptotic cells were scored in this outgrowth, a significant bystander response was observed. Also, a significant elevation in the number of terminally differentiated urothelial cells was detected. Overall, this involves a much greater fraction of cells than those which were expressing damage. Typically in the explant outgrowth 50 – 60% of the cells are normally differentiated, but this increases by 10 – 20 % when a localised region of the original tissue fragment is irradiated with the microbeam [95]. Therefore, in this model, the major response of the tissue is to switch off cell division which may be a protective response where proliferation leading to additional damage propagation is prevented [96]. Further studies with microbeams have been done in other tissue models. In recent work in commercially available skin reconstruct models it has been possible to use localised irradiation with microbeam approaches and measure the range of bystander signalling. After localised irradiation of intact 3-D skin reconstructs, these can be incubated for up to 3 days before being sectioned for histological analysis of sections at different distances away from the irradiated area. With this approach it was observed that both micronucleated and apoptotic bystander cells could be detected up to 1mm away from the originally irradiated area [97]. Further studies have utilised other tissue reconstruct models including ones aiming to mimic radon exposure in the lung [98] and observed similar long-range effects. The role of cell to cell communication either directly via GJIC or indirectly via autocrine and paracrine factors may be highly tissue specific and unlikely to be exactly mimicked in an in vitro test system, so a combination of studies with both in vitro and in vivo models will need to be developed in the future.

7. Future perspectives

Microbeams are making a significant impact on our understanding of radiation responses in cells and tissue models. They are powerful probes alongside other approaches (such as UV lasers) for following DNA damage and repair on an individual cell basis. They have a major advantage in that they allow these processes to be followed under conditions of direct physiological relevance to environmental, occupational and therapeutic doses. Future advances in biology with the impact of live cell imaging approaches will allow DNA damage processing to be carefully mapped in real-time. A major challenge is to gain further insights into subcellular radiosensitivity mechanisms by probing at the nuclear and non-nuclear levels in both cell and tissue models. These studies need to consider both spatial and temporal aspects following responses in cells through to functional biological changes. A future advance will be to translate these approaches into in vivo models to understand the responses of these particularly to low dose exposure. The technology for producing microbeam source is changing rapidly allowing finer resolution beams and more optimal integration with cell imaging approaches. This will allow high throughput approaches where biological changes occur at low frequency in response to low dose exposures of relevance to radiation risk studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Cancer Research UK [CUK] grant number C1513/A7047, the European Union NOTE project (FI6R 036465) and the US National Institutes of Health (5P01CA095227-02) for funding their work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zirkle RE, Bloom W. Irradiation of parts of individual cells. Science. 1953;117:487–493. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3045.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner DJ, Miller RC, Huang Y, Hall EJ. The biological effectiveness of raon-progeny alpha particles lll. Quality factors. Radiat Res. 1995;142:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadhim MA, Lorimore SA, Townsend KM, Goodhead DT, Buckle VJ, Wright EG. Radiation-induced genomic instability: delayed cytogenetic aberrations and apoptosis in primary human bon marrow cells. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 1995;67:287–293. doi: 10.1080/09553009514550341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marples B, Joiner MC. The Response of Chinese Hamster V79 Cells to Low Radiation Doses: Evidence of Enhanced Sensitivity of the Whole Cell Population. Radiation Research. 1993;133:41–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prise KM, Schettino G, Folkard M, Held KD. New insights on cell death from radiation exposure. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:520–528. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prise KM, O'Sullivan JM. Radiation-induced bystander signalling in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:351–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boreham DR, Dolling JA, Broome J, Maves SR, Smith BP, Mitchel REJ. Cellular adaptive response to single tracks of low-LET radiation and the effect on nonirradiated neighboring cells. Radiation Research. 2000;153:230–231. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller RC, Randers-Pehrson G, Geard CR, Hall EJ, Brenner DJ. The oncogenic transforming potential of the passage of single alpha particles through mammalian cell nuclei. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:19–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prise KM, Folkard M, Malcolmson AM, Pullar CH, Schettino G, Bowey AG, Michael BD. Single ion actions: the induction of micronuclei in V79 cells exposed to individual protons. Adv Space Res. 2000;25:2095–2101. doi: 10.1016/s0273-1177(99)01060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadhim MA, Marsden SJ, Goodhead DT, Malcolmson AM, Folkard M, Prise KM, Michael BD. Long-term genomic instability in human lymphocytes induced by single-particle irradiation. Radiat Res. 2001;155:122–126. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0122:ltgiih]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schettino G, Folkard M, Prise KM, Vojnovic B, Bowey AG, Michael BD. Low-Dose Hypersensitivity in Chinese Hamster V79 Cells Targeted with Counted Protons Using a Charged-Particle Microbeam. Radiat Res. 2001;156:526–534. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0526:ldhich]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prise KM, Belyakov OV, Folkard M, Michael BD. Studies of bystander effects in human fibroblasts using a charged particle microbeam. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 1998;74:793–798. doi: 10.1080/095530098141087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schettino G, Folkard M, Michael BD, Prise KM. Low-dose binary behavior of bystander cell killing after microbeam irradiation of a single cell with focused c(k) x rays. Radiat Res. 2005;163:332–336. doi: 10.1667/rr3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodhead DT. The initial physical damage produced by ionising radiations. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 1989;56:623–634. doi: 10.1080/09553008914551841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenner TJ, deLara CM, O'Neill P, Stevens DL. Induction and rejoining of DNA double-strand breaks in V79-4 mammalian cells following γ and α-irradiation. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 1993;64:265–273. doi: 10.1080/09553009314551421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prise KM, Pinto M, Newman HC, Michael BD. A Review of Studies of Ionizing Radiation-Induced Double-Strand Break Clustering. Radiat Res. 2001;156:572–576. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0572:arosoi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paretzke HG. Physical events of heavy ion interactions with matter. Adv Space Res. 1986;6:67–73. doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(86)90278-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosswendt B, Pszona S. The track structure of alpha-particles from the point of view of ionization-cluster formation in “nanometric” volumes of nitrogen. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2002;41:91–102. doi: 10.1007/s00411-002-0144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakob B, Scholz M, Taucher-Scholz G. Biological imaging of heavy charged-particle tracks. Radiat Res. 2003;159:676–684. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0676:biohct]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikjoo H, O'Neill P, Wilson WE, Goodhead DT. Computational approach for determining the spectrum of DNA damage induced by ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2001;156:577–583. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0577:cafdts]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson RM, Stevens DL, Goodhead DT. M-FISH analysis shows that complex chromosome aberrations induced by alpha -particle tracks are cumulative products of localized rearrangements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12167–12172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182426799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelms BE, Maser RS, Mackay JF, Lagally MG, Petrini JHJ. In situ visualisation of DNA double-strand break repair in human fibroblasts. Science. 1998;280:590–592. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Essers J, Houtsmuller AB, van Veelen L, Paulusma C, Nigg AL, Pastink A, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JH, Kanaar R. Nuclear dynamics of RAD52 group homologous recombination proteins in response to DNA damage. Embo J. 2002;21:2030–2037. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aten JA, Stap J, Krawczyk PM, van Oven CH, Hoebe RA, Essers J, Kanaar R. Dynamics of DNA double-strand breaks revealed by clustering of damaged chromosome domains. Science. 2004;303:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.1088845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asaithamby A, Uematsu N, Chatterjee A, Story MD, Burma S, Chen DJ. Repair of HZE- particle-induced DNA double-strand breaks in normal human fibroblasts. Radiat Res. 2008;169:437–446. doi: 10.1667/RR1165.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakob B, Rudolph JH, Gueven N, Lavin MF, Taucher-Scholz G. Live cell imaging of heavy-ion-induced radiation responses by beamline microscopy. Radiat Res. 2005;163:681–690. doi: 10.1667/rr3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folkard M, Prise KM, Schettino G, Shao C, Gilchrist S, Vojnovic B. New insights into the cellular response to radiation using microbeams. Nuclear Instruments and Methods B. 2005;231:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randers-Pehrson G, Geard C, Johnson G, Brenner D. Technical characteristics of the Columbia University single-ion microbeam. Radiation Research. 2000;153:221–223. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0210:tcusim]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi Y, Funayama T, Wada S, Furusawa Y, Aoki M, Shao C, Yokota Y, Sakashita T, Matsumoto Y, Kakizaki T, Hamada N. Microbeams of heavy charged particles. Biol Sci Space. 2004;18:235–240. doi: 10.2187/bss.18.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerardi S, Galeazzi G, Cherubini R. A microcollimated ion beam facility for investigations of the effects of low-dose radiation. Radiat Res. 2005;164:586–590. doi: 10.1667/rr3378.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauptner A, Dietzel S, Drexler GA, Reichart P, Krucken R, Cremer T, Friedl AA, Dollinger G. Microirradiation of cells with energetic heavy ions. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2004;42:237–245. doi: 10.1007/s00411-003-0222-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bigelow A, Garty G, Funayama T, Randers-Pehrson G, Brenner D, Geard C. Expanding the question-answering potential of single-cell microbeams at RARAF, USA. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2009;50 A:A21–28. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08134s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heiss M, Fischer BE, Jakob B, Fournier C, Becker G, Taucher-Scholz G. Targeted Irradiation of Mammalian Cells Using a Heavy-Ion Microprobe. Radiat Res. 2006;165:231–239. doi: 10.1667/rr3495.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greif K, Beverung W, Langner F, Frankenberg D, Gellhaus A, Banaz-Yasar F. The PTB microbeam: a versatile instrument for radiobiological research. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2006;122:313–315. doi: 10.1093/rpd/ncl436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heiss M, Fischer BE, Cholewa M. Status of the GSI microbeam facility for cell irradiation with single ions. Radiation Research. 2004;161:98–99. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiedler A, Reinert T, Tanner J, Butz T. DNA double strand breaks and Hsp70 expression in proton irradiated living cells. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 2007;260:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Imaseki H, Ishikawaa T, Isoa H, Konishia T, Suyaa N, Hamanoa T, Wanga X, Yasudaa N, Yukawaa M. Progress report of the single particle irradiation system to cell (SPICE) Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms. 2007;260:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folkard M, Vojnovic B, Hollis KJ, Bowey AG, Watts SJ, Schettino G, Prise KM, Michael BD. A charged particle microbeam: II A single-particle micro-collimation and detection system. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 1997;72:387–395. doi: 10.1080/095530097143167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Randers-Pehrson G, Geard CR, Johnson G, Elliston CD, Brenner DJ. The Columbia University single-ion microbeam. Radiat Res. 2001;156:210–214. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0210:tcusim]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folkard M, Schettino G, Vojnovic B, Gilchrist S, Michette AG, Pfauntsch SJ, Prise KM, Michael BD. A focused ultrasoft x-ray microbeam for targeting cells individually with submicrometer accuracy. Radiat Res. 2001;156:796–804. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0796:afuxrm]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi Y, Funayama T, Hamada N, Sakashita T, Konishi T, Imaseki H, Yasuda K, Hatashita M, Takagi K, Hatori S, Suzuki K, Yamauchi M, Yamashita S, Tomita M, Maeda M, Kobayashi K, Usami N, Wu L. Microbeam irradiation facilities for radiobiology in Japan and China. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2009;50 A:A29–47. doi: 10.1269/jrr.09009s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prewett PD, Michette AG. MOXI: a novel microfabricated zoom lens for x-ray imaging. In: Freund AK, Ishikawa T, Khounsary AM, Mancini DC, Michette AG, Oestreich S, editors. Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE) Conference Series. 2001. pp. 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sowa MB, Murphy MK, Miller JH, McDonald JC, Strom DJ, Kimmel GA. A variable- energy electron microbeam: a unique modality for targeted low-LET radiation. Radiat Res. 2005;164:695–700. doi: 10.1667/rr3463.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xing JZ, Lee J, Leadon SA, Weinfeld M, Le XC. Measuring DNA damage using capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detection. Methods. 2000;22:157–163. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumaravel TS, Vilhar B, Faux SP, Jha AN. Comet Assay measurements: a perspective. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2009;25:53–64. doi: 10.1007/s10565-007-9043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickey JS, Redon CE, Nakamura AJ, Baird BJ, Sedelnikova OA, Bonner WM. H2AX: functional roles and potential applications. Chromosoma. 2009;118:683–692. doi: 10.1007/s00412-009-0234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Attikum H, Gasser SM. Crosstalk between histone modifications during the DNA damage response. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Venkitaraman AR. Mobilization and recruitment of HP1: a bimodal response to DNA breakage. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2945–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhogal N, Jalali F, Bristow RG. Microscopic imaging of DNA repair foci in irradiated normal tissues. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:732–746. doi: 10.1080/09553000902785791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mortusewicz O, Roth W, Li N, Cardoso MC, Meisterernst M, Leonhardt H. Recruitment of RNA polymerase II cofactor PC4 to DNA damage sites. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:769–776. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li AY, Boo LM, Wang SY, Lin HH, Wang CC, Yen Y, Chen BP, Chen DJ, Ann DK. Suppression of nonhomologous end joining repair by overexpression of HMGA2. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5699–5706. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong Z, Jiang J, Lan L, Nakajima S, Kanno S, Koseki H, Yasui A. A polycomb group protein, PHF1, is involved in the response to DNA double-strand breaks in human cell. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:2939–2947. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim JS, Krasieva TB, LaMorte V, Taylor AM, Yokomori K. Specific recruitment of human cohesin to laser-induced DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45149–45153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heale JT, Ball AR, Jr, Schmiesing JA, Kim JS, Kong X, Zhou S, Hudson DF, Earnshaw WC, Yokomori K. Condensin I interacts with the PARP-1-XRCC1 complex and functions in DNA single-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2006;21:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kubota Y, Takanami T, Higashitani A, Horiuchi S. Localization of X-ray cross complementing gene 1 protein in the nuclear matrix is controlled by casein kinase II-dependent phosphorylation in response to oxidative damage. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mocquet V, Laine JP, Riedl T, Yajin Z, Lee MY, Egly JM. Sequential recruitment of the repair factors during NER: the role of XPG in initiating the resynthesis step. EMBO J. 2008;27:155–167. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoogstraten D, Bergink S, Ng JM, Verbiest VH, Luijsterburg MS, Geverts B, Raams A, Dinant C, Hoeijmakers JH, Vermeulen W, Houtsmuller AB. Versatile DNA damage detection by the global genome nucleotide excision repair protein XPC. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2850–2859. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katsumi S, Kobayashi N, Imoto K, Nakagawa A, Yamashina Y, Muramatsu T, Shirai T, Miyagawa S, Sugiura S, Hanaoka F, Matsunaga T, Nikaido O, Mori T. In situ visualization of ultraviolet-light-induced DNA damage repair in locally irradiated human fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1156–1161. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bekker-Jensen S, Lukas C, Kitagawa R, Melander F, Kastan MB, Bartek J, Lukas J. Spatial organization of the mammalian genome surveillance machinery in response to DNA strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:195–206. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461:1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim JS, Krasieva TB, Kurumizaka H, Chen DJ, Taylor AM, Yokomori K. Independent and sequential recruitment of NHEJ and HR factors to DNA damage sites in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:341–347. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lazzaro F, Giannattasio M, Puddu F, Granata M, Pellicioli A, Plevani P, Muzi-Falconi M. Checkpoint mechanisms at the intersection between DNA damage and repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lisby M, Rothstein R. Localization of checkpoint and repair proteins in eukaryotes. Biochimie. 2005;87:579–589. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tomimatsu N, Tahimic CG, Otsuki A, Burma S, Fukuhara A, Sato K, Shiota G, Oshimura M, Chen DJ, Kurimasa A. Ku70/80 Modulates ATM and ATR Signaling Pathways in Response to DNA Double Strand Breaks. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10138–10145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen BP, Uematsu N, Kobayashi J, Lerenthal Y, Krempler A, Yajima H, Lobrich M, Shiloh Y, Chen DJ. Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) is essential for DNA-PKcs phosphorylations at the Thr-2609 cluster upon DNA double strand break. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6582–6587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peng Y, Woods RG, Beamish H, Ye R, Lees-Miller SP, Lavin MF, Bedford JS. Deficiency in the catalytic subunit of DNA-dependent protein kinase causes down-regulation of ATM. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1670–1677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bartkova J, Bakkenist CJ, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE, Sehested M, Lukas J, Kastan MB, Bartek J. ATM activation in normal human tissues and testicular cancer. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:838–845. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.6.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bartkova J, Horejsi Z, Koed K, Kramer A, Tort F, Zieger K, Guldberg P, Sehested M, Nesland JM, Lukas C, Orntoft T, Lukas J, Bartek J. DNA damage response as a candidate anti-cancer barrier in early human tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;434:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nature03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Simonsson M, Qvarnstrom F, Nyman J, Johansson KA, Garmo H, Turesson I. Low-dose hypersensitive gammaH2AX response and infrequent apoptosis in epidermis from radiotherapy patients. Radiother Oncol. 2008;88:388–397. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Koike M, Sugasawa J, Yasuda M, Koike A. Tissue-specific DNA-PK-dependent H2AX phosphorylation and gamma-H2AX elimination after X-irradiation in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Koll TT, Feis SS, Wright MH, Teniola MM, Richardson MM, Robles AI, Bradsher J, Capala J, Varticovski L. HSP90 inhibitor, DMAG, synergizes with radiation of lung cancer cells by interfering with base excision and ATM-mediated DNA repair. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1985–1992. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anders M, Mattow J, Digweed M, Demuth I. Evidence for hSNM1B/Apollo functioning in the HSP70 mediated DNA damage response. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1725–1732. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dellaire G, Bazett-Jones DP. Beyond repair foci: subnuclear domains and the cellular response to DNA damage. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1864–1872. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.15.4560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Limoli CL, Ward JF. A new method for introducing double-strand breaks into cellular DNA. 1993;134:160–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rogakou EP, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner WM. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tirlapur UK, Konig K. Femtosecond near-infrared laser pulse induced strand breaks in mammalian cells. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2001;47:OL131–134. Online Pub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gomez-Godinez V, Wakida NM, Dvornikov AS, Yokomori K, Berns MW. Recruitment of DNA damage recognition and repair pathway proteins following near-IR femtosecond laser irradiation of cells. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:020505. doi: 10.1117/1.2717684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim JS, Heale JT, Zeng W, Kong X, Krasieva TB, Ball AR, Jr, Yokomori K. In situ analysis of DNA damage response and repair using laser microirradiation. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;82:377–407. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)82013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dinant C, de Jager M, Essers J, van Cappellen WA, Kanaar R, Houtsmuller AB, Vermeulen W. Activation of multiple DNA repair pathways by sub-nuclear damage induction methods. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2731–2740. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kong X, Mohanty SK, Stephens J, Heale JT, Gomez-Godinez V, Shi LZ, Kim JS, Yokomori K, Berns MW. Comparative analysis of different laser systems to study cellular responses to DNA damage in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e68. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grigaravicius P, Rapp A, Greulich KO. A direct view by immunofluorescent comet assay (IFCA) of DNA damage induced by nicking and cutting enzymes, ionizing (137)Cs radiation, UV-A laser microbeam irradiation and the radiomimetic drug bleomycin. Mutagenesis. 2009;24:191–197. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gen071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mari PO, Florea BI, Persengiev SP, Verkaik NS, Bruggenwirth HT, Modesti M, Giglia-Mari G, Bezstarosti K, Demmers JA, Luider TM, Houtsmuller AB, van Gent DC. Dynamic assembly of end-joining complexes requires interaction between Ku70/80 and XRCC4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18597–18602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609061103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Essers J, Houtsmuller AB, Kanaar R. Analysis of DNA recombination and repair proteins in living cells by photobleaching microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 2006;408:463–485. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pryde F, Khalili S, Robertson K, Selfridge J, Ritchie AM, Melton DW, Jullien D, Adachi Y. 53BP1 exchanges slowly at the sites of DNA damage and appears to require RNA for its association with chromatin. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2043–2055. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hashiguchi K, Matsumoto Y, Yasui A. Recruitment of DNA repair synthesis machinery to sites of DNA damage/repair in living human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2913–2923. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uematsu N, Weterings E, Yano K, Morotomi-Yano K, Jakob B, Taucher-Scholz G, Mari PO, van Gent DC, Chen BP, Chen DJ. Autophosphorylation of DNA-PKCS regulates its dynamics at DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:219–229. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Berkovich E, Monnat RJ, Jr, Kastan MB. Roles of ATM and NBS1 in chromatin structure modulation and DNA double-strand break repair. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:683–690. doi: 10.1038/ncb1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Siino JS, Nazarov IB, Svetlova MP, Solovjeva LV, Adamson RH, Zalenskaya IA, Yau PM, Bradbury EM, Tomilin NV. Photobleaching of GFP-labeled H2AX in chromatin: H2AX has low diffusional mobility in the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1318–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Warters RL, Hofer KG. Radionuclide toxicity in cultured mammalian cells. Elucidation of the primary site for radiation-induced division delay. Radiat Res. 1977;69:348–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu LJ, Randers-Pehrson G, Xu A, Waldren CA, Geard CR, Yu Z, Hei TK. Targeted cytoplasmic irradiation with alpha particles induces mutations in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4959–4964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shao C, Folkard M, Michael BD, Prise KM. Targeted cytoplasmic irradiation induces bystander responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13495–13500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404930101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou H, Ivanov VN, Lien YC, Davidson M, Hei TK. Mitochondrial function and nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated signaling in radiation-induced bystander effects. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2233–2240. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen S, Zhao Y, Han W, Zhao G, Zhu L, Wang J, Bao L, Jiang E, Xu A, Hei TK, Yu Z, Wu L. Mitochondria-dependent signalling pathway are involved in the early process of radiation-induced bystander effects. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1839–1844. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tartier L, Gilchrist S, Burdak-Rothkamm S, Folkard M, Prise KM. Cytoplasmic irradiation induces mitochondrial-dependent 53BP1 protein relocalization in irradiated and bystander cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5872–5879. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Belyakov OV, Folkard M, Mothersill C, Prise KM, Michael BD. Bystander-induced apoptosis and premature differentiation in primary urothelial explants after charged particle microbeam irradiation. Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 2002;99:249–251. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.rpd.a006775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Belyakov OV, Folkard M, Mothersill C, Prise KM, Michael BD. Bystander-induced differentiation: A major response to targeted irradiation of a urothelial explant model. Mutat Res. 2006;597:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Belyakov OV, Mitchell SA, Parikh D, Randers-Pehrson G, Marino SA, Amundson SA, Geard CR, Brenner DJ. Biological effects in unirradiated human tissue induced by radiation damage up to 1 mm away. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14203–14208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sedelnikova OA, Nakamura A, Kovalchuk O, Koturbash I, Mitchell SA, Marino SA, Brenner DJ, Bonner WM. DNA Double-Strand Breaks Form in Bystander Cells after Microbeam Irradiation of Three-dimensional Human Tissue Models. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4295–4302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]