Abstract

Muscle performance is closely related to the architecture and dimensions of the muscle–tendon unit and the effect of maturation on these architectural characteristics in humans is currently unknown. This study determined whether there are differences in musculo-tendinous architecture between adults and children of both sexes. Fascicle length and pennation angle were measured from ultrasound images at three sites along the length of the vastus intermedius, vastus lateralis, vastis medialis and rectus femoris muscles. Muscle volume and muscle–tendon length were measured from magnetic resonance images. Muscle physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) was calculated as the ratio of muscle volume to optimum fascicle length. Fascicle length was greater in the adult groups than in children (P < 0.05) but pennation angle did not differ between groups (P > 0.05). The ratios between fascicle and muscle length and between fascicle and tendon length were not different (P > 0.05) between adults and children for any quadriceps muscle. Quadriceps volume and PCSA of each muscle were greater in adults than children (P < 0.01) but the relative proportion of each head to the total quadriceps volume was similar in all groups. However, the difference in PCSA between adults and children (men ∼ 104% greater than boys, women ∼ 57% greater than girls) was greater (P < 0.05) than the difference in fascicle length (men ∼ 37% greater than boys, women ∼ 10% greater than girls). It is concluded that the fascicle, muscle and tendon lengthen proportionally during maturation, thus the muscle–tendon stiffness and excursion range are likely to be similar in children and adults but the relatively greater increase in PCSA than fascicle length indicates that adult muscles are better designed for force production than children’s muscles.

Keywords: architecture, force, growth, maturation, moment–angle relationship, scaling

Introduction

The functional significance of muscle size and architecture is well documented and understood (Gans & Bock, 1965; Alexander & Vernon, 1975; Bodine et al. 1982; Gans & de Vree, 1987; Zajac, 1989; Lieber & Fridén, 2000; Ward et al. 2006, 2009). The maximum force-producing potential of a muscle is largely dependent on its physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) and the excursion range and maximum shortening velocity depend on the length of the fascicles. In fact, the ratio between PCSA and fascicle length can be used to provide an insight into which of these tasks the muscle is best ‘designed’ for (Lieber & Fridén, 2000; Ward et al. 2009).

In addition, the fascicle length plays a significant role in determining the force–length properties of a muscle. Specifically, the fascicle length relative to the length of the serial tendon (fascicle : tendon length ratio) has important consequences for the contractile properties of the muscle–tendon unit (MTU) as a whole. Within a given MTU, a longer tendon (reduced fascicle : tendon length ratio) will reduce the active stiffness of the MTU necessitating a longer MTU length to achieve a similar degree of myo-filament overlap compared with an MTU with a shorter tendon (Zajac, 1989). In addition, an MTU with a tendon of a given length but short muscle fibres (small fascicle : tendon length ratio) will have a small resting MTU length compared with a muscle with longer fibres. This will increase sarcomere length at any given MTU length (Gans & Bock, 1965) and increase the excursion range of the serial sarcomeres that make up the muscle fascicle (Bodine et al. 1982). The mechanical importance of the fascicle : tendon length ratio is exemplified by the sensitivity of musculoskeletal models to this parameter (Garner & Pandy, 2003; De Groote et al. 2009).

During maturation from childhood to adulthood there are obvious, large increases in muscle size, which are accompanied by increases in fascicle length (Kubo et al. 2001) and pennation angle in some (Binzoni et al. 2001; Kurihara et al. 2007) but not all muscles (Kubo et al. 2001). As a result of these changes in muscle size and architecture it is possible that the fascicle : tendon length ratio, as well as the PCSA of the muscle, will change with maturation. Moreover, if the intra-muscular architecture variation (Blazevich et al. 2006) is different between adults and children then these previous measures of architecture from a single site may be misleading.

It would also be valuable to know if there is a scaling relationship between muscle, tendon and fascicle length in adults that is similar to that in children. Although it has been suggested that fascicle length increases proportionally to body mass0.3 (Alexander et al. 1981), a negative relationship between mass and the relative fascicle length (fascicle length per muscle length) was recently reported (Eng et al. 2008). However, this study was conducted across a wide range of species and whether this finding applies to size differences and growth within a single species is not clear. In fact, this finding is in contrast to the principle of isometry, which would suggest that the fascicle length should increase proportionally to other anatomical structures throughout maturation and growth (Alexander & Jayes, 1983). Findings from studies of humans are unclear as to whether the size and length of fascicles, muscle and tendon remain in proportion throughout maturation (Kubo et al. 2001; Kurihara et al. 2007), although it appears that they do with ageing (Morse et al. 2005). Knowledge of how muscle and tendon grow would not only provide information regarding how MTU lengthening with maturation is achieved but would potentially allow better scaling and prediction of parameters for musculoskeletal models of adults and children.

The purpose of the present study was therefore to determine whether there are differences in musculo-tendinous architecture between adults and children of both sexes and to investigate whether any structural changes occur proportionally with maturation.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 10 men, 10 women, 9 boys and 10 girls (participant demographics are presented in Table 1) volunteered for this study. The adults were aged between 23 and 35 years and were sedentary in their daily lives. The children were aged between 8 and 10 years and were not participating in any organized sport or physical activity outside school. The physical maturity of the children was not directly assessed but, based on the age range included (8–10 years for both boys and girls) and magnetic resonance image (MRI) confirmation that the growth plate of the femoral condyle was completely unfused (Grade I) in all of the children (Dvorak et al. 2007), it is likely that most children in both gender groups were of pre-pubertal (stage 1) status (Tanner, 1962). These restrictions to participant recruitment were put in place to ensure that the primary difference between the groups was the effect of pubertal maturation and that training state or early ageing effects were not confounding covariates. Participants did not perform any physical activity for 2 days prior to testing. This study was approved by the research institution’s local ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the parents/guardians of the children before the measurements.

Table 1.

The mean (SD) participant demographics.

| Age (years) | Height (m) | Mass (kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 28.2 (3.6) | 1.8 (0.08) | 78.8 (14) |

| Women | 27.4 (4.2) | 1.67 (0.08) | 64 (9.4) |

| Boys | 8.9 (0.7) | 1.38 (0.09) | 35.6 (9.5) |

| Girls | 9.4 (0.8) | 1.42 (0.07) | 42.3 (9.5) |

Magnetic resonance image protocol

Prior to the MRI scans being performed participants lay at rest in the scanning position for ∼ 15 min to allow fluid shifts to occur (Berg et al. 1993). Participants lay supine with their hip and knee joints fully extended while MRIs were taken along the entire length of the vastus intermedius (VI), vastus lateralis (VL), vastis medialis (VM) and rectus femoris (RF) MTUs of their dominant leg [turbo 3D T1, slice thickness 6.3 mm; inter-slice gap 0 mm; acquisition time 3 min 57 s; time to repetition/echo time/number of excitations (TR/TE/NEX) 40/16/1; field of view 180 × 180 mm2; matrix 256 × 256 pixels; 0.2-T E-scan; Esaote Biomedica, Genoa, Italy].

Muscle and tendon length

The length of each quadriceps femoris head muscle was measured from the MRIs. The proximal tendon and its origin could not be clearly identified from the MRIs for any of the muscles. Therefore, the tendon length for each muscle was calculated as the difference between length of the entire MTU and muscle length. The length of the MTU was estimated based on the distance between the bony landmarks typically considered as the origin and insertion of each muscle. The origins of the VI, VL and VM muscles extend along the linea aspera, with the most proximal attachment point being at the level of the greater trochanter, which we considered to be the origin of these three muscles. The RF MTU originates at the anterior inferior iliac spine. The insertion of the MTU of all muscles was the superior border of the patella. These landmarks were identified from the MRIs and the distance between them considered as the length of the respective MTU.

Muscle architecture

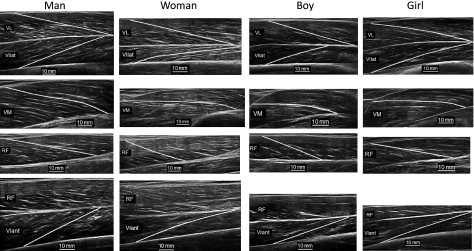

The fascicle architecture of each quadriceps muscle head was measured with the participants lying supine and their hip and knee joints fully extended. Ultrasound images (104 mm probe length; MyLab 70; Esaote Biomedica) were taken at three sites along the length of each muscle head. These sites were identified based on relative distances between the superior border of the patella and the anterior superior iliac spine (patella–iliac distance), identified through palpation. For the VM the sites were 5, 22 and 39%, for the VL they were 22, 39 and 56% and for the RF they were 39, 56 and 73% of the patella–iliac distance. The VI was considered to be made up of two distinct parts: the anterior VI (VIant) and lateral VI (VIlat). The VIlat architecture was imaged at 22, 39 and 56% and the VIant was imaged at 39, 56 and 73% of the patella–iliac distance. Example ultrasound images from the central region of each muscle head are presented in Fig. 1. These sites have previously been reported to correspond to the proximal, central and distal thirds of the length of these muscles (Blazevich et al. 2006) in adults and pilot testing for this study had shown that this was also the case in the children.

Fig. 1.

Example ultrasound images from the central region of each muscle head in a man, woman, boy and girl. VL, vastus lateralis; VIlat, lateral vastus intermedius; VIant, anterior vastus intermedius; VM, vastus medialis; RF, rectus femoris.

In each image three fascicles were identified and their length was measured, taking into account any curvature, from the origin at the superficial aponeurosis to the insertion at the deep aponeurosis. The angle of pennation of each fascicle was measured as the angle between the fascicle and the deep aponeurosis at the point of insertion. All measurements were made using ImageJ (version 1.38×; NIH, USA). The mean length and angle of pennation of the three fascicles was taken to represent the architecture of that region of the muscle.

It was not possible to obtain ultrasound images with a clear depiction of the fascicles for all regions of each muscle head in every participant. This problem was predominantly limited to imaging of the entire fascicle length rather than the pennation angle and probably reflects curvature of the fascicles outside the 2D ultrasound scanning plane. Interestingly, the regions that could not be imaged varied between groups. They were the proximal region of the VIant in six men, the proximal region of the VM in six girls and the distal RF in four boys and four girls.

As a result the mean fascicle length along the entire length of each muscle head (f) could not be calculated using all three regions for all four muscles. The approach taken was to exclude any region in which architecture could not be imaged in all participants. In the VL, f could be calculated as the mean of the three regions. However, in the RF, f was calculated from just the central and proximal regions and in the VM, f was calculated from the central and distal regions only. The VI was considered as a single muscle with an f equal to the mean of all three regions of the VIlat and the central and distal regions of the VIant.

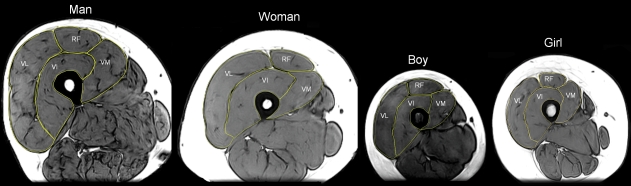

Physiological cross-sectional area

The PCSA of each quadriceps muscle was calculated as the ratio between muscle volume and optimum fascicle length. Muscle volume was measured as the sum of the cross-sectional areas (OsiriX dicom viewer version 2.2.1; Osirix Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland) of the serial axial-plane MRIs (example MRIs are presented in Fig. 2) multiplied by the thickness of each slice (1.89 cm). In most cases the boundaries of each muscle could be clearly seen. In a few instances the separation between VI and VL was not so clear, mainly towards the origin of the two heads, and guidance was provided by the axial-plane MRIs above and below the region of interest to estimate the boundaries of each muscle head. There was also some difficulty in identifying the axial-plane MRI in which the VM muscle terminated proximally as its is entangled within the adductor muscle group but appropriate image contrast and zoom made this possible. The muscle volume data have been presented previously (O’Brien et al. 2009c) but are included here for completeness. The optimum fascicle length (fo) was calculated using the following equation (Maganaris, 2004; Ward et al. 2006, 2009):

Fig. 2.

Example axial-plane magnetic resonance images of the quadriceps femoris muscle at mid-thigh length from a man, woman, boy and girl. The boundaries of the rectus femoris (RF), vastus lateralis (VL), vastus intermedius (VI) and vastus medialis (VM) muscles are marked.

fo = f (2.7/resting sarcomere length)

where 2.7 represents the optimum sarcomere length (in μm) (Walker & Schrodt, 1974) and resting sacromere length was obtained from cadaveric data (VL 2.14, VM 2.24, VI 2.17 and RF 2.42 μm) (Ward et al. 2009). The ratio between PCSA and fo in each quadriceps head was calculated for each group to provide an indication of whether the muscle is best suited for force production or large excursions and shortening velocities.

The same individual obtained all of the ultrasound and MRI scans and performed the morphometric analyses.

Statistical analysis

Using only the participants from which fascicle architecture could be imaged in all three regions of a specific muscle, a separate mixed 3 × 4 (region × group) analysis of variance (anova) was used for each muscle to test for differences in fascicle length and pennation angle between regions within each group and between groups within each region. Differences between groups in f, fo, muscle length, tendon length, volume and PCSA of each muscle were tested for with a Wilks’ Lambda anova. The f : muscle length, f : tendon length and f : patella–iliac distance were then calculated for each muscle. A Wilks’ Lambda anova was then performed to test for differences in these three ratios between the groups for each separate muscle. Pearson’s correlations were performed between f and muscle, tendon and patella–iliac distance for each muscle. The ratio between PCSA and fo in each quadriceps head was also analysed using a Wilks’ Lambda anova. All statistical tests were performed in spss (version 16.0.1) with two-tailed significance.

All results are presented as mean and SEM. Significance was accepted at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

The fascicle lengths in each region of the four knee extensor muscles were generally greater in adults compared with children. In all muscles there was a significant main effect of fascicle length between the regions (P < 0.05). In the VL, VIant and VIlat muscles there were no differences in the regional variation of fascicle length between groups. In the VM and RF there were significant region by group statistical interactions (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). Pennation angle did not differ between groups in any region of any muscle. Pennation angle differed between regions of the VM, VIant and VIlat but not in the VL and RF. There were no significant region by group statistical interactions for any muscle for pennation angle. The mean (SEM) fascicle length and pennation angle for the three regions of each muscle in the separate groups are presented with the post-hoc pair-wise comparisons in Tables 2–6.

Table 2.

Fascicle length and pennation angle of the proximal, central and distal thirds of the vastus lateralis.

| Fascicle length (cm) |

Pennation angle (°) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Central | Proximal | Distal | Central | Proximal | |

| Men | 85.3A (3.42) | 87.2b,g (3.07) | 85b,g (2.88) | 17.2 (1.44) | 15.3 (1.28) | 17.1 (1.45) |

| Women | 72.2A (2.3) | 82.4b,g (2.65) | 78.3b (3.7) | 17.1 (1.74) | 15.8 (1.02) | 17.1 (1.06) |

| Boys | 60.3m,w (1.93) | 64.4m,w (3.7) | 63.2m,w (2.88) | 16 (2.1) | 15.8 (0.6) | 16.2 (0.96) |

| Girls | 61m,w (3.09) | 68.3m,w (2.25) | 69.4m (2.64) | 18.2 (1.36) | 17 (1.31) | 15.2 (0.79) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups within region are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

No significant length or pennation differences between regions within any group.

Table 6.

Fascicle length and pennation angle of the proximal, central and distal thirds of the rectus femoris.

| Fascicle length (cm) |

Pennation angle (°) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Central | Proximal | Distal | Central | Proximal | |

| Men | 85.9Ac,p (4) | 66.3Ad (2.02) | 61.7gd (2.32) | 16.7p (1.68) | 22.2 (1.62) | 23.6d (1.42) |

| Women | 61.1m (4.3) | 57.1m (1.5) | 53.9 (2.08) | 19.3 (1.59) | 22 (0.9) | 19.9 (1.19) |

| Boys | 57.3m (5.44) | 52.4m (2.88) | 50.3 (3.04) | 21.1 (2.38) | 24 (1.24) | 22.3 (1.52) |

| Girls | 58.9m (3.85) | 55.6m (1.61) | 52.5 (2.23) | 20.7 (2.42) | 21.6 (1.74) | 19.7 (1.13) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups within region are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; g, girls).

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between regions within group are indicated with subscript text (d, distal; c, central; p, proximal).

Table 3.

Fascicle length and pennation angle of the proximal, central and distal thirds of the vastus medialis.

| Fascicle length (cm) |

Pennation angle (°) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Central | Proximal | Distal | Central | Proximal | |

| Men | 78.9Ac (2.82) | 91.9Ad (3.81) | 86.2b,g (3.62) | 36p,c (2.15) | 27.4d,p (2.21) | 21.5d,c (1.6) |

| Women | 69.5m (3.52) | 76.7m,b (4.01) | 73.5b,g (3.37) | 31.6p (1.79) | 27.7p (2.98) | 16.8d,c (1.21) |

| Boys | 61m (2.21) | 60.4m,w (2) | 53.6m,w (1.64) | 33c,p (1.58) | 20.7d (1.89) | 20.6d (1.05) |

| Girls | 66.2m (2.06) | 68m (1.99) | 53.9m,w (7.04) | 31.2p (1.81) | 24.7p (3.49) | 16.3d,c (2.32) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups within region are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between regions within group are indicated with subscript text (d, distal; c, central; p, proximal).

Table 4.

Fascicle length and pennation angle of the proximal, central and distal thirds of the lateral vastus intermedius.

| Fascicle length (cm) |

Pennation angle (°) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Central | Proximal | Distal | Central | Proximal | |

| Men | 67.6b (2.9) | 65.2p (3.1) | 76.3bc (3.82) | 10.7p (1.3) | 13.9 (1.13) | 16.6d (2.16) |

| Women | 57c,p (1.9) | 69.7bd (2.98) | 68.8d (2.44) | 11.1 (0.94) | 12.7 (0.93) | 12.9 (1.02) |

| Boys | 48.2p (4.45) | 50.8 (4.82) | 60.1d (3.76) | 11.8 (1.07) | 14.9 (1.28) | 15.4 (1.02) |

| Girls | 55.6 (2.66) | 59.5 (2.19) | 60.1 (2.03) | 11.4 (1.43) | 14.9 (1.72) | 15.6 (0.89) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups within region are indicated with superscript text (b, boys).

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between regions within group are indicated with subscript text (d, distal; c, central; p, proximal).

Table 5.

Fascicle length and pennation angle of the proximal, central and distal thirds of the anterior vastus intermedius.

| Fascicle length (cm) |

Pennation angle (°) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal | Central | Proximal | Distal | Central | Proximal | |

| Men | 71.7b,g (2.73) | 67.8b (1.84) | 76.9b,g (2.27) | 11.8c,p (0.65) | 15.5d (0.75) | 22.4d (4.64) |

| Women | 67.4bp (2.71) | 68.9b,g (3.58) | 77.9b,gd (3.07) | 14.1 (0.95) | 16 (2.34) | 18.4 (2.47) |

| Boys | 50.9A (2.31) | 53.3m,w (2.14) | 57.2m,w (2.94) | 11.1p (0.87) | 12.5 (0.43) | 16.7d (1.42) |

| Girls | 61.1m,b (2.13) | 60.2w (3.6) | 61.4m,w (1.16) | 12.3c (0.55) | 14.1d (1.16) | 14.8 (1.16) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups within region are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between regions within group are indicated with subscript text (d, distal; c, central; p, proximal).

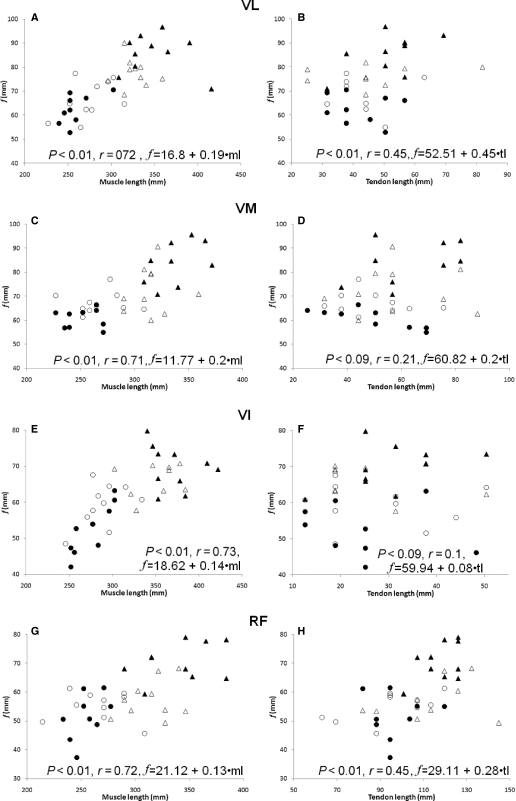

Significant main effects indicated that f and muscle lengths were greater in adults than children (P < 0.01), with no differences between men and women or between boys and girls (Tables 7–10). Tendon length was similar between all groups for the vasti muscles but there were significant differences in the length of the RF tendon between men and either child group. The mean f : muscle length and f : tendon length ratios were similar between groups in all four quadriceps muscles (Tables 7–10). When combining the data from all groups, f correlated with muscle length for all muscles (P < 0.01, r = 0.7–0.73) but f correlated with tendon length only in the VL and RF (P < 0.01, r = 0.45 for both) (Fig. 3).

Table 7.

Mean fascicle length and its ratio to muscle and tendon length in the vastus lateralis.

| Fascicle length (mm) | Muscle length (mm) | Fascicle : muscle length | Tendon length (mm) | Fascicle : tendon length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 85.9b,g (2.5) | 349.7b,g (10.6) | 0.25 (0.01) | 51.7 (3.4) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Women | 77.7b (1.9) | 326.9b,g (5.7) | 0.24 (0.01) | 49.7 (4.8) | 1.7 (0.17) |

| Boys | 62.6m,w (2) | 258.4m,w (6.2) | 0.24 (0.01) | 42.2 (3) | 1.6 (0.13) |

| Girls | 66.4m (2.5) | 274.7m,w (8.3) | 0.24 (0.01) | 42.2 (2.8) | 1.6 (0.11) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated with superscript text (m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

Mean fascicle length and its ratio to muscle and tendon length in the rectus femoris.

| Fascicle length (mm) | Muscle length (mm) | Fascicle : muscle length | Tendon length (mm) | Fascicle : tendon length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 70.4A (2.1) | 334.5b,g (11.7) | 0.21 (0.01) | 124.1b,g (7.7) | 0.58 (0.02) |

| Women | 57.3m (2.1) | 314.4b,g (7.1) | 0.18 (0.01) | 112.1 (6.1) | 0.52 (0.03) |

| Boys | 51.5m (2.6) | 254.7m,w (4.8) | 0.2 (0.01) | 96.9m (3.8) | 0.54 (0.04) |

| Girls | 55.2m (1.6) | 265.9m,w (8.7) | 0.21 (0.01) | 95.1m (5.7) | 0.60 (0.03) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

Fig. 3.

Correlations of fascicle length (f) with muscle length (A, C, E, G) and tendon length (B, D, F, H) for the four quadriceps heads [men (▴), women (▵), boys (•) and girls (○)]. Regression equations are presented for the prediction of f from muscle length or tendon length. VI, vastus intermedius; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus medialis; RF, rectus femoris.

Table 8.

Mean fascicle length and its ratio to muscle and tendon length in the vastis medialis.

| Fascicle length (mm) | Muscle length (mm) | Fascicle : muscle length | Tendon length (mm) | Fascicle : tendon length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 85.4A (3.1) | 338.3b,g (6.5) | 0.25 (0.01) | 63 (4.8) | 1.42 (0.11) |

| Women | 72.5m,b (3.1) | 317.8b,g (5.9) | 0.23 (0.01) | 58.8 (6.1) | 1.37 (0.14) |

| Boys | 60.7m (1.3) | 251.5m,w (5.6) | 0.24 (0.01) | 49 (5.3) | 1.40 (0.2) |

| Girls | 67.1m (1.4) | 267.1m,w (7.3) | 0.25 (0.01) | 49.8 (4.2) | 1.44 (0.13) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated with superscript text (A, all other groups; m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

Table 9.

Mean fascicle length and its ratio to muscle and tendon length in the vastus intermedius.

| Fascicle length (mm) | Muscle length (mm) | Fascicle : muscle length | Tendon length (mm) | Fascicle : tendon length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 69.7b,g (1.9) | 371.1b,g (8.7) | 0.19 (0.01) | 30.2 (3.2) | 2.56 (0.3) |

| Women | 66.9b (1.5) | 317.3b,g (8.7) | 0.21 (0.01) | 26.6 (3.6) | 2.82 (0.3) |

| Boys | 52.4m,w (2.4) | 275.6m,w (7.2) | 0.19 (0.005) | 25 (3.9) | 2.54 (0.41) |

| Girls | 59.2m (1.9) | 288.5m,w (7.7) | 0.21 (0.01) | 28.4 (4.0) | 2.52 (0.37) |

Significant differences (P < 0.05) between groups are indicated with superscript text (m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

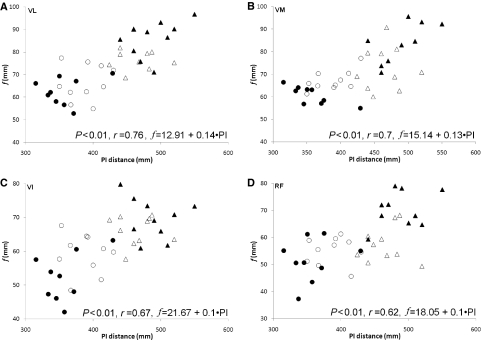

The patella–iliac distance was greater in adults than children (P < 0.01) and there were also no significant differences in the f : patella–iliac distance ratio between groups in any muscle (Table 11). There was a significant correlation between f and patella–iliac distance for all muscles when including all participants (P < 0.01, r = 0.62–0.76) (Fig. 4).

Table 11.

Patella–iliac distance and its ratio to f in each muscle.

|

f:patella–iliac distance ratio |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patella–iliac distance (mm) | VL | VM | VI | RF | |

| Men | 488b,g (10.4) | 0.18 (0.005) | 0.18 (0.006) | 0.14 (0.006) | 0.14 (0.004) |

| Women | 465b,g (9) | 0.17 (0.005) | 0.16 (0.007) | 0.14 (0.004) | 0.12 (0.005) |

| Boys | 356.9m,w (11) | 0.18 (0.007) | 0.17 (0.008) | 0.15 (0.006) | 0.14 (0.008) |

| Girls | 387.5m,w (8.7) | 0.17 (0.007) | 0.17 (0.003) | 0.15 (0.006) | 0.14 (0.005) |

Significant differences between groups are indicated with superscript text (m, men; w, women; b, boys; g, girls).

RF, rectus femoris; VI, vastus intermedius; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastis medialis.

Fig. 4.

Correlations of fascicle length (f) with patella–iliac (PI) distance for the four quadriceps heads [men (▴), women (▵), boys (•) and girls (○)]. Regression equations are presented for the prediction of f from PI distance. (A) VL, vastus lateralis; (B) VM, vastus medialis; (C) VI, vastus intermedius; (D) RF, rectus femoris.

The optimum fascicle length, volume and PCSA of each quadriceps muscle were greater in adults than children (P < 0.01) (Table 12). However, the relative proportions of each muscle to total quadriceps volume and PCSA was similar between groups (volume: 34% VL, 24% VM, 28% VI, 14% RF; PCSA: 31% VL, 21% VM, 30% VI, 18% RF).

Table 12.

Muscle volume, optimum fascicle length (fo) and physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) calculated for each quadriceps muscle head.

| VL |

VM |

VI |

RF |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (cm3) | fo (mm) | PCSA (cm2) | Volume (cm3) | fo (mm) | PCSA (cm2) | Volume (cm3) | fo (mm) | PCSA (cm2) | Volume (cm3) | fo (mm) | PCSA (cm2) | |

| Men | 691.2 (46.8) | 108.3 (3.2) | 64.0 (4.5) | 523.2 (42.3) | 102.9 (3.8) | 50.7 (3.7) | 557.6 (45.3) | 86.8 (2.4) | 64.2 (4.9) | 280.7 (20.9) | 78.5 (2.3) | 35.7 (2.3) |

| Women | 455.9 (34.3) | 98.0 (2.3) | 46.6 (3.4) | 350.7 (27.8) | 87.4 (3.7) | 40.5 (3.4) | 373.7 (25.6) | 82.3 (1.7) | 45.5 (3.1) | 178.8 (10.4) | 64.0 (2.3) | 28.3 (2.1) |

| Boys | 237.3 (13.3) | 79.0 (2.4) | 30.7 (1.5) | 157.4 (9.6) | 73.2 (1.5) | 22.2 (1.4) | 198.1 (15.2) | 65.2 (2.8) | 31.5 (1.0) | 116.0 (7.5) | 57.5 (2.8) | 20.6 (1.2) |

| Girls | 267.1 (16.3) | 83.8 (3.1) | 32.0 (2.0) | 182.3 (13.0) | 80.9 (1.7) | 22.7 (1.8) | 228.8 (14.6) | 73.7 (2.3) | 30.8 (1.3) | 111.1 (7.3) | 61.6 (1.7) | 18.0 (1.1) |

RF, rectus femoris; VI, vastus intermedius; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastis medialis.

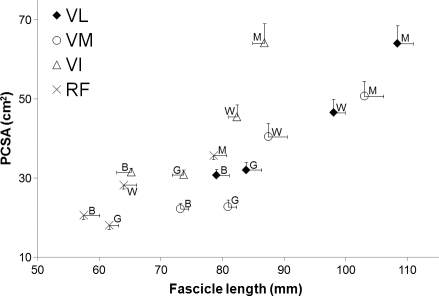

The mean PCSA of the four quadriceps heads was 104% greater in men than boys and 57% greater in women than girls. The mean fo of the four quadriceps heads was 37% greater in men than boys and 10% greater in women than girls. Consequently, the ratio of PCSA to fo was generally greater in adults than children (Fig. 5). Statistical differences (P < 0.05) existed between men and boys in the VL, VM and VI and between women and girls in the VM, VI and RF. Statistical differences between men and women only existed in the VL but no differences existed between boys and girls in any muscle head.

Fig. 5.

The relationship between physiological cross-sectional area (PCSA) and optimum fascicle length in each quadriceps head. Data points are the mean ± SE for each group (M, men; W, women; B, boys; G, girls) and muscle head. VI, vastus intermedius; VL, vastus lateralis; VM, vastus medialis; RF, rectus femoris.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether there are differences in musculo-tendinous architecture between adults and children of both genders and to investigate whether any structural changes occur proportionally with maturation and whether these may have functional consequences for movement. It was found that muscle volume and muscle and fascicle lengths were greater in adults than children but there were no differences in the angle of pennation. The f : muscle length ratios were equal in adults and children of both genders, and the correlations were significant and strong. The f : tendon length ratio was also similar between groups, with the correlations being significant for the VL and RF MTUs. These results indicate that the differences in the length of the knee extensor MTUs between adults and children and between men and women are predominantly due to an almost proportional increase in fascicle, muscle and tendon lengths. As a result, in the VL and RF, the optimum MTU length and sarcomere excursion range are unlikely to alter due to changes in muscle architecture with maturation. In the VM and VI, although there is between-subject variability, the mean ratio in each group remained constant, so the same conclusions can be tentatively made. This finding is supported by the similar joint moment–angle relationship between adults and children (O’Brien et al. 2009a).

As a consequence of these results, provided that the stiffness of the quadriceps tendon is proportional to the maximum tendon force in all groups [this is the case for the patellar tendon, so it is possible that it is also the case for the quadriceps tendon (O’Brien et al. 2009b)], the sarcomeres in adult and child muscles would undergo a similar absolute elongation or shortening as a result of similar relative MTU lengthening or shortening. The longer fascicles in adults allow a greater absolute maximum shortening velocity compared with the children. However, the similar ratios of f to muscle and tendon length in all groups mean that the maximum relative shortening velocity (MTU lengths/s) will be equal in adults and children.

It was found that muscle length was significantly greater in adults than children and also tendon length was greater in adults than children but this did not reach statistical significance for some tendons (Tables 7–10). It was also found that fascicle : tendon and fascicle : muscle length ratios were similar between all groups (Tables 7–10). The lack of statistical difference between the tendon lengths of adults and children represents the short tendon lengths and large intra-group variability, rather than a disproportionate lengthening of muscle and tendon. This is confirmed by the ratio of tendon length to total MTU length, which was similar between groups in each muscle (∼ 13, 16, 8 and 28% in VL, VM, VI and RF, respectively), and the significant correlations with f in most cases.

The increase in muscle volume with maturation is due to the increase in f (Table 7–10) and PCSA (Table 12), indicating the addition of sarcomeres in series and in parallel. As the increase in PCSA is greater than the increase in fo (Fig. 5), it appears as though with maturation the muscle is adopting an architectural design that is better suited for maximal force production. However, the increase in PCSA was mainly due to an increase in muscle volume, which was partly caused by an increase in fascicle length, and this factor alone would indicate a greater excursion range and shortening velocity in the adults. Typically, intervention-induced hypertrophy (e.g. by resistance training) is accompanied by increases in pennation angle (Kawakami et al. 1995; Kearns et al. 2000; Reeves et al. 2004; Seynnes et al. 2007; Suetta et al. 2008). In contrast to this conventional ‘model’ of hypertrophy, but in accordance with previous findings in the VL (Kubo et al. 2001), we found no differences between adults and children in pennation angle. This can be explained by the muscle lengthening creating space for the addition of parallel sarcomeres along the length of the aponeurosis, unlike hypertrophy in intervention models when the additional attachment area is acquired by increasing pennation angle.

The contribution of each muscle head to total quadriceps volume and PCSA was similar between groups, indicating that the growth of the quadriceps MTU as a whole is due to the similar relative increase in each separate muscle. The proportional size of each quadriceps head and scaling of fascicle, muscle and tendon lengths between adults and children of both genders, which mirrors findings in the elderly (Morse et al. 2005), is in keeping with the principles of isometry and in contrast to the inter-species variations reported by Eng et al. (2008). This indicates that the negative relationship between the fascicle : muscle length ratio and mass reported in that study is a result of inter-species differences and cannot be applied to scaling fascicle lengths between large and small or mature and immature animals within the same species, at least for humans. The finding that f correlates with the externally measured patella–iliac distance equally in all groups (Table 11, Fig. 4) allows the use of the regression equations presented in Fig. 4 for the estimation of f in all individuals for musculoskeletal modelling. Further, the muscle length for all quadriceps heads and tendon length for the VL and RF can be predicted from the calculated f for muscles that are known to constitute a proportionally equal fraction of the entire quadriceps volume. Care must be taken in the interpretation and application of the f : tendon length ratios in the VM and VI, and future study should examine the nature of the apparent variability. It appears that, with respect to the MTUs of the quadriceps group, children can be considered as small-scale adults. The exact mechanism that governs this proportional growth is not clear but there may be a ‘regulatory’ factor governing muscle growth to ensure that muscle coordination patterns developed in childhood remain similar throughout maturation.

This study found intra-muscular differences in the fascicle length and pennation angle in the VM, VI and RF. This is in accordance with previous findings on pennation angle in adults, although the pattern between regions is slightly different (Blazevich et al. 2006). These differences are possibly a result of variation between the participants in the two studies. The participants here were sedentary, whereas, based on the exclusion criteria, those in the previous study may have been more active. This intra-muscle variation in pennation angle was not different between the groups in any muscle. In contrast, there were differences in the intra-muscle fascicle length variation between groups in the VM and RF muscles. These results show that maturation does not alter the pennation of muscle but that disproportionate increases in fascicle length may occur between the different regions of a muscle.

In the calculation of f for each muscle head not all regions could be accounted for due to the inability to obtain adequate images in the proximal VM and VIant and distal RF (as described in Materials and methods). This could have had a confounding effect of the subsequent analysis of the calculated f. However, the proximal VM, although it represents approximately one-third of the total muscle length, consists of only a small portion of the total VM muscle volume due to its ‘tapered’ shape. Consequently, the proximal VM contains relatively few fascicles compared with the central and distal thirds and so will make a relatively small contribution to the actual overall f. In the VIant, fascicle length does not change significantly between regions and therefore the distal and central regions will equally represent the proximal region and the calculated f would not be adversely affected. Thus, we remain confident in the validity of the present findings for the vasti muscles. However, the RF showed intra-muscle fascicle length variation that differed between groups and, in contrast to the proximal VM, the distal RF constitutes a major portion of the total volume. Consequently, the calculated RF f may not be equally representative of the whole muscle in all groups. Nonetheless, we considered it more appropriate to calculate the f from the regions that could be imaged in all groups, rather than include inconsistent data in the analysis for each group. Future study should seek to determine the validity of this approach.

The present findings of similar ratios for f : muscle length and f : patella–iliac distance in the quadriceps muscles, confirmed with significant correlations, of adults and children are in contrast to the findings of Kubo et al. (2001) who reported an increased fascicle : femur length in the VL with adolescence. These differences are potentially explained by the previous authors using measures of fascicle length from a single site along the muscle. However, care must be taken if applying the present findings to pubertal children, as it is known that bone growth occurs prior to muscle lengthening and the ratios may only be restored post-puberty when the muscle lengthening has been able to ‘catch-up’ with bone growth.

From the present study of the knee extensor muscle group it can be concluded that, with maturation, the lengthening of the MTU is achieved by a proportional increase in muscle, tendon and f lengths. Thus, with respect to the length parameters in the MTU, children can be considered as small-scale adults. Similarly, the proportional contribution of each muscle head to total quadriceps PCSA remained constant in each group, so with respect to the cross-sectional size of the muscle, children can again be considered as small-scale adults. However, the increase in PCSA is relatively greater than the increase in fo, indicating that the same scaling parameters cannot be applied between adults and children to the muscle as a whole and separate approaches are required for f and PCSA. Moreover, these findings suggest that the quadriceps femoris muscle design in adults is better suited to force production than that in children.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Adrian W. Midgley of The University of Hull for his advice and assistance in the statistical analyses.

References

- Table 10.Alexander RM, Jayes AS. A dynamic similarity hypothesis for the gaits of quadrupedal mammals. J Zool. 1983;201:135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RM, Vernon A. The dimensions of knee and ankle muscles and the forces they exert. J Hum Mov Stud. 1975;1:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RM, Jayes AS, Maloiy GMO, et al. Allometry of the leg muscles of mammals. J Zool. 1981;194:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Berg H, Tedner B, Tesch P. Changes in lower limb muscle cross-sectional area and tissue fluid volume after transition from standing to supine. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993;14:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binzoni T, Bianchi S, Hanquinet S, et al. Human gastrocnemius medialis pennation angle as a function of age: from newborn to the elderly. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2001;20:293–298. doi: 10.2114/jpa.20.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazevich AJ, Gill ND, Zhou S. Intra- and intermuscular variation in human quadriceps femoris architecture assessed in vivo. J Anat. 2006;209:289–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine SC, Roy RR, Meadows DA, et al. Architectural, histochemical, and contractile characteristics of a unique biarticular muscle – the cat semi-tendinosus. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:192–201. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groote F, Van Campen A, Jonkers I, et al. Cape Town: 2009. Sensitivity of dynamometric experiment to muscle parameters. Abstract No. 117. In XXIInd Congress of the International Society of Biomechanics. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak J, George J, Junge A, et al. Age determination by magnetic resonance imaging of the wrist in adolescent male football players. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:45–52. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2006.031021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng CM, Smallwood LH, Rainiero MP, et al. Scaling of muscle architecture and fiber types in the rat hindlimb. J Exp Biol. 2008;211:2336–2345. doi: 10.1242/jeb.017640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C, Bock W. The functional significance of muscle architecture: a theoretical analysis. Ergeb Anat Entwicklungsgesch. 1965;38:115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans C, de Vree F. Functional bases of fiber length and angulation in muscle. J Morphol. 1987;192:63–85. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1051920106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BA, Pandy MG. Estimation of musculotendon properties in the human upper limb. Ann Biomed Eng. 2003;31:207–220. doi: 10.1114/1.1540105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Abe T, Kuno SY, et al. Training-induced changes in muscle architecture and specific tension. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1995;72:37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF00964112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns CF, Abe T, Brechue WF. Muscle enlargement in sumo wrestlers includes increased muscle fascicle length. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;83:289–296. doi: 10.1007/s004210000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K, Kanehisa H, Kawakami Y, et al. Growth changes in the elastic properties of human tendon structures. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22:138–143. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara T, Kanehisa H, Abe T, et al. Gastrocnemius muscle architecture and external tendon length in young boys. J Biomech. 2007;40:S690. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Fridén J. Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1647–1666. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200011)23:11<1647::aid-mus1>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maganaris CN. A predictive model of moment-angle characteristics in human skeletal muscle: application and validation in muscles across the ankle joint. J Theor Biol. 2004;230:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse CI, Thom JM, Birch KM, et al. Changes in triceps surae muscle architecture with sarcopenia. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;183:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2004.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien T, Reeves N, Baltzopoulos V, et al. The effects of agonist and antagonist muscle activation on the knee extension moment-angle relationship in adults and children. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009a;106:849–856. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien T, Reeves N, Baltzopoulos V, et al. Mechanical properties of the patellar tendon in adults and children. J Biomech. 2009b. in press doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed]

- O’Brien T, Reeves N, Jones D, et al. Strong relationships exist between muscle volume, joint power and whole-body external mechanical power in adults and children. Exp Physiol. 2009c;94:731–738. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.045062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves ND, Narici MV, Maganaris CN. In vivo human muscle structure and function: adaptations to resistance training in old age. Exp Physiol. 2004;89:675–689. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.027797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seynnes OR, de Boer M, Narici MV. Early skeletal muscle hypertrophy and architectural changes in response to high-intensity resistance training. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:368–373. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00789.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetta C, Andersen JL, Dalgas U, et al. Resistance training induces qualitative changes in muscle morphology, muscle architecture, and muscle function in elderly postoperative patients. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:180–186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01354.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JM. Growth at Adolescence. London: Blackwell, Scientific Publications; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Walker SM, Schrodt GR. I. Segment lengths and thin filament periods in skeletal-muscle fibres of rhesus-monkey and human. Anat Rec. 1974;178:63–81. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091780107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SR, Hentzen ER, Smallwood LH, et al. Rotator cuff muscle architecture: implications for glenohumeral stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;448:157–163. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194680.94882.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SR, Eng CM, Smallwood LH, et al. Are current measurements of lower extremity muscle architecture accu-rate? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0594-8. DOI 10.1007/s11999-008-0594-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac FE. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 1989;17:359–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]