Abstract

Motivation: Document similarity metrics such as PubMed's ‘Find related articles’ feature, which have been primarily used to identify studies with similar topics, can now also be used to detect duplicated or potentially plagiarized papers within literature reference databases. However, the CPU-intensive nature of document comparison has limited MEDLINE text similarity studies to the comparison of abstracts, which constitute only a small fraction of a publication's total text. Extending searches to include text archived by online search engines would drastically increase comparison ability. For large-scale studies, submitting short phrases encased in direct quotes to search engines for exact matches would be optimal for both individual queries and programmatic interfaces. We have derived a method of analyzing statistically improbable phrases (SIPs) for assistance in identifying duplicate content.

Results: When applied to MEDLINE citations, this method substantially improves upon previous algorithms in the detection of duplication citations, yielding a precision and recall of 78.9% (versus 50.3% for eTBLAST) and 99.6% (versus 99.8% for eTBLAST), respectively.

Availability: Similar citations identified by this work are freely accessible in the Déjà vu database, under the SIP discovery method category at http://dejavu.vbi.vt.edu/dejavu/

Contact: merrami@collin.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

Most scientists today face intense competition in the race for peer recognition, visibility and international acclaim. Academic distinction is gained based on the number of peer-reviewed publications in highly circulated journals. This intense pressure to publish, not only to advance, but also simply to sustain one's career, is summarized in the adage, ‘publish or perish’. Because substantial amounts of time and resources are needed to complete scientific studies, there is often a natural desire to seek maximum benefits for the costs incurred. Unfortunately, this sometimes results in authors publishing the same piece of work multiple times or, worse, publishing someone else work as their own.

Some forms of duplicated content, such as those appearing in publications of conference proceedings, important updates to studies, confirmation of contested results in controversial studies and translations of important findings, may no doubt be beneficial to the scientific community. Duplication is seen as unethical when the primary intent is to deceive peers, supervisors and/or journal editors with false claims of novel data. Given the large number of papers published annually, the large diversity of journals with overlapping interests in which to publish, and the uneven access to journal publication content, it is not unreasonable to assume that the discovery of such duplication is rare. The recent development of algorithmic methods to systematically process published literature and identify instances of duplicated/plagiarized text as accurately as possible should serve as an effective deterrent to authors considering this dubious path. Unfortunately, the methods in place now have a very limited reach, and are confined to abstracts and titles only.

Several cases of duplicate publication have been described in the literature with the aim of identifying characteristics and signatures suggestive of duplication. However, the automatic detection of duplicate publication is still in its infancy. The majority of studies on this topic have been relegated to specific fields because most tools lack the technology necessary to quickly and efficiently identify cases of duplication (Bailey, 2002; Barnard and Overbeke, 1993; Blancett et al., 1995; Bloemenkamp et al., 1999; Chennagiri et al., 2004; Durani, 2006; Gotzsche, 1989; Kostoff et al., 2006; Martinson et al., 2005; Mojon-Azzi et al., 2004; Roig, 2005; Rosenthal et al., 2003; Schein and Paladugu, 2001). Findings among these studies consistently estimate the duplicate publication rate in biomedical literature to be a few percent.

We previously reported one of the first automated processes to identify highly similar citations in the MEDLINE database, many of which were later confirmed as duplicates where substantial portions of text were simply copied and pasted from the earlier to the later publication (Long et al., 2009). Conducted via text comparison algorithm eTBLAST, this process successfully identified duplicate citations in the biomedical literature with high specificity (over 99%) at the expense of a low sensitivity (∼50%) (Errami et al., 2007, 2008). We also performed the first large-scale automated detection of duplicate publications in MEDLINE (Errami and Garner, 2008) and deposited these findings into the Déjà vu database (Errami et al., 2009). Our estimate of ∼200 000 duplicate publications in MEDLINE is consistent with previous reports (Martinson et al., 2005; von Elm et al., 2004).

One weakness of this process, however, is that when calibrated for high specificity, eTBLAST omits about one-half of the potential duplicate publications, and thus has a low sensitivity of detection. We therefore present a new approach to identify potential duplicate citations overlooked by the eTBLAST method and provide succinct search strings suitable for use in online searches. This approach uses ‘statistically improbable phrases’ (SIPs), a concept similar to that implemented by Amazon.com (http://www.amazon.com/gp/search-inside/sipshelp.html). Since Amazon.com reveals very little about how SIPs are calculated or can be used by readers and customers, we have established our own process to define, score and use SIPs to discover previously unidentified pairs of duplicate citations within MEDLINE.

2 METHODS

2.1 Hardware and programming tools

Our analysis was performed using a PC with 3.0 GHz processors and 4 GB RAM under Linux (Suze 10.3). The various scripts for this work were written in Python (http://www.python.org), but the interpreter was Jython 2.2.1 (http://www.jython.org) rather than Python. This allowed us to combine the simple and elegant scripting syntax of Python with the powerful indexing capabilities of Lucene, written in Java. Jython fully interprets Python scripts and also provides simple ways to call Java native libraries.

2.2 MEDLINE datasets

This work was conducted using the entire MEDLINE database as of January 2009. The database was stored as pairs of values (PMID, ‘title+abstract’) in a MySQL database (http://www.mysql.com) and combined with a Lucene index (http://lucene.apache.org) for fast and efficient retrieval. The indexing mode was set to keep the text structure intact and include punctuation signs, e.g. ‘thus’ and ‘thus’, are distinct. From this database, we constructed three test sets of citation pairs—two sets with no duplicate pairs and one set of duplicates. The first set of 5000 non-duplicate pairs was obtained by pairing 10 000 randomly selected MEDLINE abstracts. Almost all pairs of articles in this set are non-duplicates because the occurrence of duplicate citations in MEDLINE is low enough that the probability of two randomly selected citations being duplicates is almost zero (Errami et al., 2008). That is, if 1% of papers are duplicates, then the odds of selecting a duplicate pair is .01*.01 = 0.0001. A second set of 5000 pairs was obtained by randomly pairing 10 000 related but non-duplicate citations. For each of the pairs in this second set, one citation was randomly chosen from MEDLINE and then paired with one article returned from PubMed's ‘Related articles’ feature, excluding the top-most related article. We already know that if a citation has a duplicate, it appears as the top-most related article 73% of the time (Errami et al., 2008). However, if the duplicate is not the top-most related article, there is a low probability of the duplicate appearing in PubMed's related article list (data not shown). Therefore, pairs of related articles are likely not duplicates if the top-most related article is not chosen. The third test set contained 1300 manually verified duplicate citation pairs obtained from the Déjà vu database (Errami et al., 2008).

In order to estimate the performance of SIPs for the identification of highly similar citations, a set of 10 000 random citation pairs, as well as a 171 MEDLINE duplicates (citations tagged as duplicates in MEDLINE), were used to estimate the algorithm performance, following our previously reported method (Errami et al., 2008).

2.3 SIP analysis

2.3.1 SIP scoring as the product of successive bigram transition probabilities

In this study, the words ‘sentences’ and ‘phrases’ are used interchangeably without underlying grammatical notion. Both words simply refer to a set of n words in a particular order. As a measure of SIP quality, we established a scoring scheme based on an n-gram model of word to word transition probabilities. In an ideal n-gram model, the n-th word depends on the n − 1 previous words and the transition probability from word 1 to word n is P(wn | wn−1, wn−2,…, w1). Assuming a model where n = 2, i.e. a string is 2 words in length, we counted 164.3 million bigrams in the 2009 version of MEDLINE and calculated their associated transition probabilities as the likelihood of word B following word A. Since there are almost 16 million unique words in MEDLINE, if every word was equally likely to follow another, there would be 2.7*1016 possible bigrams. This equates to an average of 10.3 possible words B likely to follow each unique word A, assuming a non-linear distribution. Extrapolating this to approximate the number of possible 6-grams produces close to two trillion combinations of words, each with its own associated probability. Thus, it is impractical to use a 6-gram model because its many possible combinations do not permit the efficient storage, indexing and searching of a database of n-gram expressions and their transition probabilities. Therefore, we approximated the transition probabilities by decomposing n-grams into successive bigrams. The transition probability for an n-gram is then the product of the transition probabilities obtained for the pairs of words in the n-gram:

Bigram probabilities for MEDLINE were calculated using Python and the Natural Language ToolKit (NLTK) package (http://nltk.sourceforge.net). We chose the phrase size for this study to be six words, and obtained probabilities for 6-grams ranging from 10−22 to 1. For each phrase, we defined its probability of being observed in another document as score = −log(P).

2.3.2 Measuring citation similarity using SIP score ratios

For each pair of citations, the SIP score ratio was defined as follows:

Six-word phrases common to both citations were identified by moving a six-word window on the target citation one word at a time. A SIP score was determined for each phrase's individual probability of being observed in MEDLINE, and the scores were summed. This sum is denoted Sfound because it is the sum of the scores of the SIPs found in both citations.

For whichever citation of the pair had fewer words, the SIP score was obtained by summing the scores of all its SIPs. This sum is denoted Smax because it is the score that would be obtained for Sfound if the two citations were identical.

The score ratio for the two citations was calculated as score ratio = Sfound/Smax. Score ratio is a measure of the degree of similarity between the two citations and ranges from zero, if the two citations have no SIPs in common, to one, if the citations are identical.

2.3.3 SIP performance evaluation

In order to evaluate SIP performance, we estimated sensitivity (recall), specificity, positive predictive value (precision) and negative predictive value as described previously for the search engine eTBLAST (Errami et al., 2008).

2.3.4 SIP comparison with eTBLAST

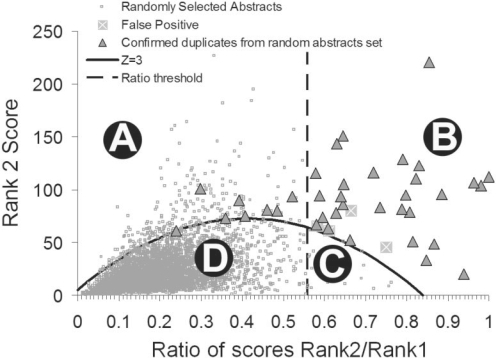

We have previously shown that eTBLAST can be used to detect highly similar citations (Errami et al., 2008). The calibration of eTBLAST for the detection of duplicate citations in MEDLINE has been described in detail (Errami et al., 2008). Briefly, when the title and abstract of a MEDLINE citation are queried against the MEDLINE database using eTBLAST, the algorithm returns a list of citations in order of their similarity to the query, as well as a similarity score for each. The most similar citation is, of course, the citation itself, labeled the Rank 1 citation. We label the most similar non-identical citation the Rank 2 citation, the second most similar non-identical citation Rank 3, etc. Figure 1 displays the similarity scores of Rank 2 citations plotted against the ratios of Rank 2 to Rank 1 similarity scores. The division of this plot into four distinct regions separates the citations pairs into groups with the following characteristics:

Fig. 1.

Four regions in the 2D space used for eTBLAST calibration to detect highly similar citations. Region B is the region in which eTBLAST predicts citations to be highly similar. Regions A and C do not contain many duplicate pairs of citations. Region D contains most MEDLINE citations and therefore most of the duplicate citations missed by eTBLAST. This figure is a modification of Figure 2 in Reference (14).

Region A: despite relatively high eTBLAST scores, the ratios of Rank 2 to Rank 1 scores are too low to merit classification of these pairs as highly similar while still maintaining high sensitivity and specificity.

Region B: highly similar citation pairs with a specificity >99% and a sensitivity of ∼50%. Separation of this region was specifically chosen to maximize specificity at the expense of sensitivity.

Region C: despite high score ratios, the Rank 1 and Rank 2 scores are too low for eTBLAST to achieve acceptable performance in the detection of potential duplicate pairs. This region is small and relatively unpopulated.

Region D: because most of the citations in this region have very little in common, both the similarity scores and score ratios are low. eTBLAST is considered ineffective at this point. Most citation pairs in MEDLINE, whether related, duplicates, or not, fall into this region. It is important to note that this region contains most of the potential duplicate pairs missed by eTBLAST due to specificity constraints.

SIPs proved successful in the identification of duplicate citation pairs in Regions B and C. Because Region A contained very few (<20) known duplicates (data not shown), we focused on using SIPs to identify duplicate citation pairs contained in Region D.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Identification of the smallest number of words able to constitute a SIP

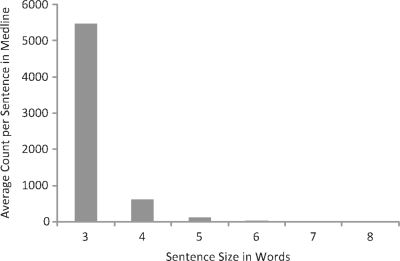

To identify the minimum number of successive words needed to constitute a SIP for use in searches and comparisons, 6 sets of 200 random abstracts were created and scanned using an n-word-window where n is the number of words, ranging from 3 to 8. To minimize the bias that occurs when smaller phrases are found, different sets of 200 abstracts were used for each value of n. Therefore, counts of common longer phrases (i.e. five words) will not be biased if two pairs of citations have common shorter phrases (i.e. three or four words). The number of SIPs and abstracts used are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Abstract and sentence counts used to identify the smallest SIP size

| Sentence size (words) | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Count in 200 abstracts | 24 239 | 26 845 | 26 468 | 24 782 | 25 608 | 22 197 |

For each sentence size, the cumulative sentence count and the average count per sentence in MEDLINE were calculated. The cumulative sentence count is the sum of the counts of all sentences of size n. The average count is the cumulative count divided by the number of sentences used, ranging from 5470 for 3 word-sentences to 2 for 8-word sentences. We chose to set the standard SIP size to six words because it represents the smallest possible sentence size for which the average count is acceptably small (22 versus 109 for 5-word sentences). See Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative average count per sentence in MEDLINE.

3.2 SIPs outperform eTBLAST in the identification of highly similar citations

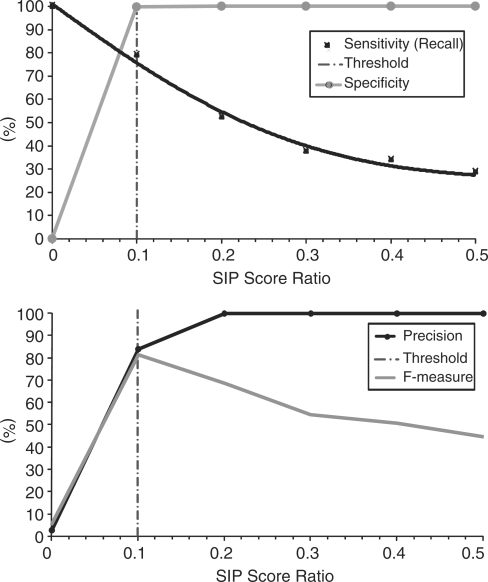

We examined SIP performance for the detection of duplicate publications as a function of the SIP score ratio threshold. The best compromise between precision and recall is obtained at a threshold of 0.1 (F-measure = 81.4%), as shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 3.

SIP duplicate detection performance evaluation as a function of the SIP score ratio.

The compared statistics presented in Table 2 show that because of the substantial increase in sensitivity, SIPs largely outperform eTBLAST in the detection of duplication publications.

Table 2.

Comparison of SIPs and eTBLAST in the detection of duplicate publications

| % | eTBLAST (ratio 0.46) | SIPs (ratio 0.1) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (recall) | 50.3 | 78.9 |

| Specificity | 99.8 | 99.6 |

| Positive predictive value (precision) | 87.8 | 84 |

| Negative predictive value | 99.3 | 99.4 |

| F-measure | 63.7 | 81.4 |

F-measure is the harmonic mean f precision and recall.

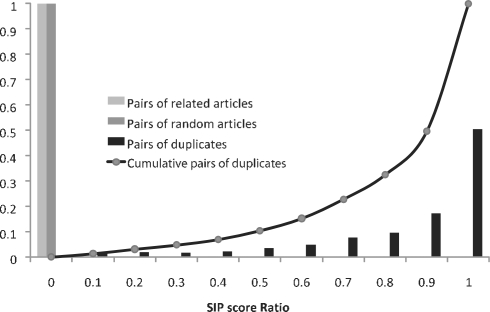

To confirm our results, SIP overlap was analyzed in the three sets of randomly selected citation pairs, related citation pairs and duplicate citation pairs. Summarized in Figure 4, these results verify that, although the same SIP is seldom found in two random articles or two related but non-duplicate articles, one or more identical SIPs are commonly found in both abstracts of a duplicate pair.

Fig. 4.

SIP score ratios between 5000 randomly paired citations, 5000 related but non-duplicate citation pairs and 1300 duplicate citation pairs, all obtained from Déjà vu. Fraction represents the proportion of citation pairs found with a particular SIP score ratio. In the case of related articles, all pairs have a SIP score ratio below 0.1.

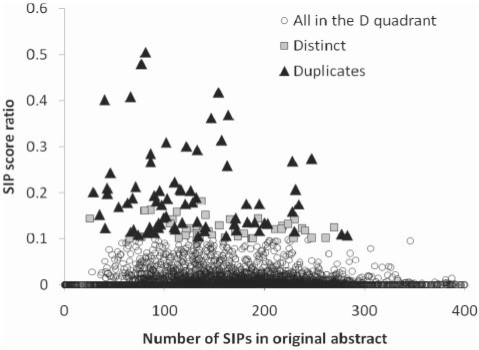

3.3 SIPs identify duplicate citations when eTBLAST cannot

To test the SIP method for identifying duplicate citation pairs not found by eTBLAST, 10 000 citation pairs were selected from region D of Figure 1. SIP scores were calculated for each of the citations and the score ratio was subsequently calculated for each pair. Beginning with the highest score ratios, pairs of citations were compared by eye to determine whether or not they were duplicates. Findings are summarized in Figure 5. All citation pairs with score ratios above 0.2 were duplicates. As the score ratio decreased below 0.2, the false positive rate of duplicates increased. Optimum performance was obtained with a score ratio of 0.1, a threshold for which 65% [65/(65 + 35)] of the pairs were duplicates. These results confirm that SIP analysis identifies with near 100% specificity the duplicate citation pairs not amenable to analysis by eTBLAST.

Fig. 5.

A total of 10 000 citations predicted as not highly similar by eTBLAST and submitted to a SIP analysis. The SIP ratio represents the SIP similarity between two citations. The X-axis of this figure is non-discriminatory and is used to improve readability of the figure.

4 DISCUSSION

SIPs have been shown to provide a more sensitive method of duplicate identification than eTBLAST, the only tool currently used to identify duplicate citations. We have demonstrated that the SIP method performs well in areas where eTBLAST operates with low sensitivity. Indeed, eTBLAST has been shown to underperform in abstracts whose text similarity is low and whose size is small, i.e. below four sentences (data not shown). SIPs also outperform eTBLAST in computation power. Whereas eTBLAST runs on a 40 CPU cluster and typically compares one abstract to all others in PubMed in ∼40 s to 1 min, the SIPs of an abstract are searched through PubMed in 69 s on average and the process can be run on a single CPU. Although the parallelization of the SIP code has not been performed on a cluster of 40 CPUs, it would likely result in a substantial gain of speed when compared with eTBLAST.

In spite of this enhanced performance, the false positive rate of SIP analysis is roughly equivalent to that of eTBLAST. False positives are highly similar citations not otherwise considered to be duplicates. For these cases, the use of a text similarity tool (using a bag of word approach like eTBLAST or short similar sentences with SIPs) would fail because text similarity does not account for natural syntactic inconsistencies such as synonym use or grammatical variations.

When using an appropriate threshold for the SIP score ratio—0.1 in this analysis—few false negatives were found. Although we cannot measure the exact number without visually inspecting thousands of pairs, we estimate the false negative rate of SIP analysis to be ∼18% when calculated using duplicates tagged in PubMed.

Both eTBLAST and SIP analysis use exceedingly simple text comparison techniques compared to advanced natural language processing algorithms, yet these tools have proven effective at identifying the majority of duplicate citations. The exhaustive identification of all duplicates in MEDLINE will necessitate the development of more sophisticated tools to analyze grammar and extract meaning from sentences rather than rely on word comparisons only. Unfortunately, increased awareness of such technology could lead to an ‘arms race’, whereby authors wishing to plagiarize seek to exploit these areas of weakness in order to avoid detection. However, since most publications are now stored electronically, these authors will have to contend with the possibility that although the technology needed to detect these exploitations is not available now, it may be in the near future—at which point any hidden indiscretions may quickly rise to the surface.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Wayne Fisher for helpful comments and discussion and Linda Gunn for administrative assistance.

Funding: Hudson Foundation; National Institutes of Health/National Library of Medicine (R01 grant number LM009758-01).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Bailey BJ. Duplicate publication in the field of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:211–216. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.122698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard H, Overbeke AJ. [Duplicate publication of original manuscripts in and from the nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde] Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 1993;137:593–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blancett SS, et al. Duplicate publication in the nursing literature. Image J. Nurs. Sch. 1995;27:51–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1995.tb00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemenkamp DG, et al. [duplicate publication of articles in the dutch journal of medicine in 1996] Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 1999;143:2150–2153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chennagiri R.JR, et al. Duplicate publication in the journal of hand surgery. J. Hand Surg. Br. 2004;29:625–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durani P. Duplicate publications: redundancy in plastic surgery literature. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2006;59:975–977. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errami M, Garner H. A tale of two citations. Nature. 2008;451:397–399. doi: 10.1038/451397a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errami M, et al. Etblast: a web server to identify expert reviewers, appropriate journals and similar publications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W12–W15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errami M, et al. Deja vu-a study of duplicate citations in Medline. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:243–249. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errami M, et al. Deja vu: a database of highly similar citations in the scientific literature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D921–D924. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotzsche PC. Multiple publication of reports of drug trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1989;36:429–432. doi: 10.1007/BF00558064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostoff RN, et al. Duplicate publication and ‘paper inflation’ in the fractals literature. Sci. Eng. Ethics. 2006;12:543–554. doi: 10.1007/s11948-006-0052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long TC, et al. Responding to possible plagiarism. Science. 2009;323:1293–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1167408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson BC, et al. Scientists behaving badly. Nature. 2005;435:737–738. doi: 10.1038/435737a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojon-Azzi SM, et al. Redundant publications in scientific ophthalmologic journals: the tip of the iceberg? Ophthalmology. 2004;111:863–866. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig M. Re-using text from one's own previously published papers: an exploratory study of potential self-plagiarism. Psychol. Rep. 2005;97:43–49. doi: 10.2466/pr0.97.1.43-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal EL, et al. Duplicate publications in the otolaryngology literature. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:772–774. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein M, Paladugu R. Redundant surgical publications: tip of the iceberg? Surgery. 2001;129:655–661. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.114549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Elm E, et al. Different patterns of duplicate publication: an analysis of articles used in systematic reviews. JAMA. 2004;291:974–980. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.8.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]