Abstract

Sodium/proton exchangers (NHX) are key players in the plant response to salinity and have a central role in establishing ion homeostasis. NHXs can be localized in the tonoplast or plasma membranes, where they exchange sodium ions for protons, resulting in sodium ions being removed from the cytosol into the vacuole or extracellular space. The expression of most plant NHX genes is modulated by exposure of the organisms to salt stress or water stress. We explored the regulation of the vacuolar NHX1 gene from the salt-tolerant sugar beet plant (BvNHX1) using Arabidopsis plants transformed with an array of constructs of BvHNX1::GUS, and the expression patterns were characterized using histological and quantitative assays. The 5′ UTR of BvNHX1, including its intron, does not modulate the activity of the promoter. Serial deletions show that a 337 bp promoter fragment sufficed for driving activity that indistinguishable from that of the full-length (2,464 bp) promoter. Mutating four putative cis-acting elements within the 337 bp promoter fragment revealed that MYB transcription factor(s) are involved in the activation of the expression of BvNHX1 upon exposure to salt and water stresses. Gel mobility shift assay confirmed that the WT but not the mutated MYB binding site is bound by nuclear protein extracted from salt-stressed Beta vulgaris leaves.

Keywords: Abiotic stress, Arabidopsis, Betavulgaris, MYB, NHX, Promoter activity, Sodium/proton exchanger, Sugar beet

Introduction

Salinity and drought are the major abiotic stresses limiting the production of crop plants worldwide (Zhu 2001; Munns 2002). Plants exposed to these stress conditions respond in biochemical, physiological and molecular levels to establish a new homeostasis that would enable them to survive the stress condition (Hasegawa et al. 2000; Serrano and Rodriguez-Navarro 2001; Zhu 2001, 2003; Bohnert et al. 2006; Pardo et al. 2006; Sahi et al. 2006). Sodium/proton exchangers (NHX) are major players in maintaining ion homeostasis (Blumwald 2000; Serrano and Rodriguez-Navarro 2001; Pardo et al. 2006; Sahi et al. 2006). These membrane-bound antiporters utilize electrochemical gradient of protons across the tonoplast or plasma membrane to transport sodium or potassium ions into the vacuole or sodium ions outside the cell, respectively (Blumwald 2000; Serrano and Rodriguez-Navarro 2001; Zhu 2003). The overexpression of tonoplast NHXs was shown to improve plant salt tolerance (Yamaguchi and Blumwald 2005; Apse and Blumwald 2007). In agreement with this finding, decreased activity of tonoplast NHX resulted in increased salt sensitivity (Apse et al. 2003; Sottosanto et al. 2007).

Vacuolar NHXs were cloned from a number of glycophilic and halophilic plant species (Blumwald and Poole 1985; Barkla et al. 1995; Fukuda et al. 1998; Hamada et al. 2001; Yamaguchi et al. 2001; Xia et al. 2002; Aharon et al. 2003; Wu et al. 2004; Kagami and Suzuki 2005; Vasekina et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2005; Jiu et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2008). It was suggested that the activity of vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporters differ in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive plants. In agreement with this notion, following salt stress the induction of NHX genes is higher in salt-tolerant plants than in salt-sensitive plants (Chauhan et al. 2000; Hamada et al. 2001; Shi and Zhu 2002; Xia et al. 2002; Yokoi et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2008). In addition, comparison of the transcriptomes of salt-sensitive Arabidopsis thaliana with that of the related tolerant species Thellungiella halophila (salsuginea) (Taji et al. 2004; Gong et al. 2005; Wong et al. 2006) suggested that these plants mainly differ in the expression levels and expression patterns of stress-related genes and ion transporters.

A large number of regulatory genes are involved in signaling pathways that are responsive to abiotic stresses (Chen and Zhu 2004). Salt and water stresses involve a number of signaling pathways, some of which are ABA dependent (Hasegawa et al. 2000; Zhu 2002; Chen and Zhu 2004; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006). A large number of transcription factors have been shown to be associated in the regulation of expression of target stress-inducible genes. Osmotic stress signaling pathway involves the AREB/ABF and DREB2 transcription factors, which bind the ABRE/CE and DRE/CRT cis-acting elements, respectively (reviewed by Zhu 2002; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006). Other transcription factors such as MYB, MYC, NAC and AP2/ERF were also shown to be involved in the regulation of genes activity by these abiotic stresses (Zhu 2002; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006).

Tonoplasts of the salt-tolerant sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) plant were shown to possess high Na+/H+-exchange activity (Blumwald et al. 1987; Blumwald and Poole 1987; Pantoja et al. 1990). NHX activity was correlated with the salinity tolerance of B. vulgaris cell cultures (Blumwald and Poole 1987). A cDNA encoding BvNHX1 was isolated (Xia et al. 2002). The BvNHX1 transcript levels in both the suspension cell culture and whole plants increased following salt treatment and this increase was concomitant with elevated BvNHX1 protein and vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter activity.

Here, the promoter of BvNHX1 was cloned and its activity was studied in transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the BvNHX1::GUS construct. Interestingly, the promoter of BvNHX1 does not contain ABRE or DRE cis-acting elements, common in promoters of osmotic stress regulated genes. The minimal 337 bp promoter sequence that was up-regulated by salt treatment and osmotic stress was identified by constructs containing serial deletions of the promoter. A number of potential cis-acting element sequences were mutated to evaluate their possible role in stress-modulated expression. Of these mutations only that in the binding site for the MYB transcription factor abolished the salt stress and water stress response.

Materials and methods

Cloning of the BvNHX1 promoter

Sugar beet genomic DNA was digested with DraI, EcoRV, PvuII, or StuI and ligated to GenomeWalker™ adapter using the Clontech GenomeWalker™ Universal Kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Screening for BvNHX1 upstream sequences was performed using general primer and gene-specific primers according to the protocol in the instructions manual. Two steps of DNA walking were performed. For the first step, the isolation of genomic DNA fragment containing partial promoter sequence and 5′ UTR, the primers used were: ptH, GCGAAGCTTCGACGGCCCGGGCTG; ptN AACTGCTCCACCATGGCTTCACATAC. The primers used for the second step (cloning of distal promoter) were: GSP6-5, CCCAGAAACCCAAGTTACAGAAAAG; BvP1, CAAGGCCCAATGCAAGTGACAAATG; BvP2, GTGTGGAGGAGAGAGAGTCGTGTTG.

Construction of promoter serial deletions

Deletions were prepared by PCR using a combination of either Bv-ShortEcoRI and each of the five primers designated Bv+NNNBamHI (where NNN stands for the primer position), or Bv-LongEcoRI and each of the five Bv+NNNBamHI primers, or the primer Bv+UTRBamHI. PCR was done using the Takara EX-Taq. Products were isolated from gels, digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and subcloned into the respective sites of the pCAMBIA 1391Z vector. The serial deletions forward primers were: Bv+1BamHI, ATTGGATCCTCATGTCGAAGAGGACAAT; Bv+271BamHI, ATTGGATCCTCTATGGTGCCCTGTATG; Bv+535BamHI, ATTGGATCCGTGCATATTTATGATGAGATAG; Bv+803BamHI, ATTGGATCCACAGACATACATGCATCTG; Bv+1042BamHI, ATTGGATCCGAGACGGTCTAATTTTAGTAC; Bv+UTRBamHI, ATTGGATCCACGTCTGCCATAATTTTG. The serial deletions reverse primers were: Bv-ShortEcoRI, CCAGAATTCAGTAGAAAAATCAGGAAATAG; Bv-LongEcoRI, CCAGAATTCACACCAAACAACCACAAT for the cloning promoter sequences without or with 5′ UTR, respectively.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis of promoter sequences was performed using the QuikChange II® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) employing the following mutation-containing primer pairs (mutation in bold): MYB 1AT, CTTAAAAATTATTGGATTAATTCTCTTCTTACTCGAGAATTGCATTAAACTAATCAC and GTGATTAGTTTAATGCAATTCTCGAGTAAGAAGAGAATTAATCCAATAATTTTTAAG; MYB ST1, CCAAAAAAAAAAAAAATCACTAAAAAATGGATCCATTCATTATTCGATTAATTCTCTTTC and GAAAGAGAATTAATCGAATAATGAATGGATCCATTTTTTAGTGATTTTTTTTTTTTTTGG; MYC, GGATTAATTCTCTTCTTAATAACTCTAGACATTAAACTAATCACTAAAAAATTTTTG and CAAAAATTTTTTAGTGATTAGTTTAATGTCTAGAGTTATTAAGAAGAGAATTAATCC; napA, TAAAAATAAACGATTTTTTATAAGACCTCGAGTTTCCTTTTATATTCCTTCTGC and GCAGAAGGAATATAAAAGGAAACTCGAGGTCTTATAAAAAATCGTTTATTTTTA. The mutated sequences were designed to contain a unique restriction site to assist in the selection of plasmids containing mutated sequences. First screening was performed by PCR amplification of the promoter sequence using Bv-ShortEcoRI and Bv+271BamHI primers (see above), followed by digestion with the respective restriction enzyme. Mutations were further confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Plant material and transformation

Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia; Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center, Columbus, OH, USA) were grown at 25°C and 50% humidity under a 12 h light/12 h dark regime. The plants were grown either in pots or in Petri dishes containing 0.5× MS medium solidified by 0.7% agar. Transformation vectors containing the respective constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium GV3101 cells, and used for genetic transformation of Arabidopsis (Clough and Bent 1998). Homozygous T2 and T3 generation transformed plants with a single transgene insert each were selected on hygromycin and used in this study. Beta vulgaris seeds (Genesis seeds Ltd., Rehovot, Israel) were sown in potting mix and were grown at 28°C and 50% humidity under a 16 h light/8 h dark regime.

GUS activity

Histochemical staining of GUS was performed essentially as described (Jefferson 1987). Quantitative GUS activity was assayed spectrophotometrically using p-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, The Netherlands) (Jefferson 1987).

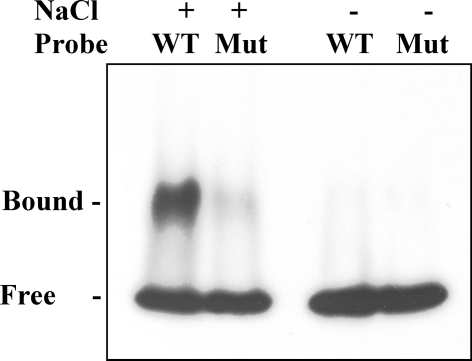

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Four-week-old seedlings were treated with 0.2 M NaCl for 24 h. Leaves were harvested, nuclei and nuclear proteins were prepared as previously described (Giuliano et al. 1988). EMSA was preformed as described (Shkolnik and Bar-Zvi 2008). Mixtures containing 2.4 μg of each forward and reverse oligonucleotides containing WT (ggTAACCAtataTAACCAaaTAACCAatttaaTAACCA, ggTGGTTAttaaatTGGTTAttTGGTTAtataTGGTTA) or mutated (ggCTCGAGtataCTCGAGaaCTCGAGatttaaCTCGAG, ggCTCGAGttaaatCTCGAGttCTCGAGtataCTCGAG) MYB binding sites were annealed by heating for 100°C and slowly cooling to RT. WT and mutated MYB binding sites are shown in CAPS, and linkers in small letters. Annealed oligonucleotides were end-labeled using Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and [α-32P]dCTP. Free nucleotides were removed by gel filtration, and the resulting labeled dsDNAs were used as probes for EMSA. Nuclear proteins (1.2 μg) were preincubated at RT for 10 min in a reaction mix contained in a final volume of 20 μl: 20 mM Hepes KOH pH 8, 50 mM KCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 12.5 ng poly(dI-dC).poly(dI-dC) (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). End-labeled DNA probe (1 μl, 3,000 cpm) was added, and mix was incubated for an additional 20 min. Reaction mixes were loaded onto 5% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.25× TBE buffer (22.25 mM Tris–borate, 0.5 mM EDTA). Samples were electrophoresed at 30 V, gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Results

Cloning of the BvNHX1 promoter

GenomeWalker B. vulgaris libraries were screened for upstream sequences using a gene-specific primer, designed from the 5′ UTR sequences of BvNHX1 cDNA (Xia et al. 2002) and a 370 bp upstream of the translation start ATG start codon sequence was localized. The first amplification round yielded a 704 bp fragment. To clone the DNA sequence comprised 704 bp promoter DNA fragment and the 5′ UTR, genomic DNA was used as a template for the amplification using ptH and ptN primers, corresponding to the upstream and downstream sequences of this DNA fragment, respectively. PCR reactions using genomic DNA template and ptH and ptN primers to amplify the DNA sequence of the 704 bp promoter fragment cloned in the first round of gene walking and 5′ UTR GeneWalking using ptN and GSP6-5 resulted in a DNA fragment corresponding to sequences 1 and upstream of the translation start codon, respectively. The expected size of the PCR product was 1,073 bp. The amplified sequence was 1,678 bp long and sequencing analysis revealed that the DNA encoding the 5′ UTR of the BvNHX1 gene is interrupted by a 605-bp long intron.

A second round of walking was preformed using the gene-specific primers BvP1 and BvP2 which were designed from sequences in the 704 bp fragment and yielded a 911 bp DNA fragment. The final combined promoter sequence comprised 2,464 bp upstream the translation start codon, composed of 1,378 bp promoter, 304 bp 5′ UTR exon I, 605 bp intron and 200 bp 5′ UTR exon II (Fig. 1a).

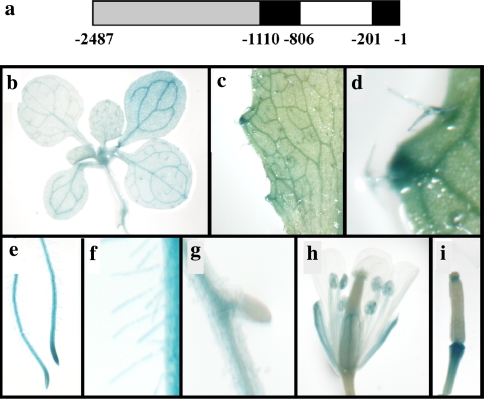

Fig. 1.

Expression pattern of the full-size BvNHX1 promoter. a Scheme of full-size BvNHX1 promoter structure. Upstream promoter sequence, 5′ UTR, and intron are marked in gray, black and white, respectively. Nucleotides are numbered in according to the translation start ATG start sequence. b–i Arabidopsis plants expressing the 2,487 bp BvNHX1::GUS constructs were grown under non-stressed conditions. Histochemical staining of GUS was performed as described in “Materials and methods”. b Shoot of soil grown plant. c Section of a mature leaf. d Close-up of the edge of the leaf shown in (c). e Primary roots. f Root hairs. g Emerging lateral root. h Flower. i Silique

Expression pattern of the BvNHX1 gene

To study the expression pattern of BvNHX1, we produced transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the GUS reporter gene driven by the 2,464 bp BvNHX1 sequence starting from 23 bp upstream of the translation start codon (construct L1::GUS). Histochemical GUS staining showed that the promoter was active in all vegetative tissues (Fig. 1b–g). In addition, high expression levels were detected in hydathodes and trichomes (Fig. 1c, d). The promoter was not highly active in guard cells and the roots showed a higher staining intensity at the tips and elongation zones (Fig. 1e). The BvNHX1 promoter was expressed in root hairs (Fig. 1f) but was not active in emerging lateral roots (Fig. 1g). Sepals and anthers were stained, whereas petals and carpels were not (Fig. 1h). Expression in pedicels was detected at the fruit stage but not at the flower stage (Fig. 1h, i).

To study the salt-induced expression of the BvNHX1 promoter, seeds expressing the L1::GUS construct (Fig. 2a) were germinated in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. Seedlings were harvested 2 weeks later, and GUS activity was determined (Fig. 2b, c). The exposure of the seedlings to 50 mM NaCl did not affect seedling growth, but resulted in a marked increase in promoter activity. The expression levels observed with this physiologically relevant long-term mild stress were much higher than those obtained with a brief exposure of non-stressed seedlings to high-salt (>0.25 M) concentrations (not shown) according to the stress application protocol used by others (e.g., Shi and Zhu 2002). Na2SO4 and mannitol resulted in similar levels of GUS activation to that obtained using NaCl (Fig. 2c), suggesting that the activity can also be induced by osmotic stress. Interestingly, a similar concentration of KCl resulted in higher expression rates. ABA, on the other hand, had a slight, statistically non-significant increase in GUS activity. The various mild stress treatments resulted in less than 30% differences in the size of the seedlings.

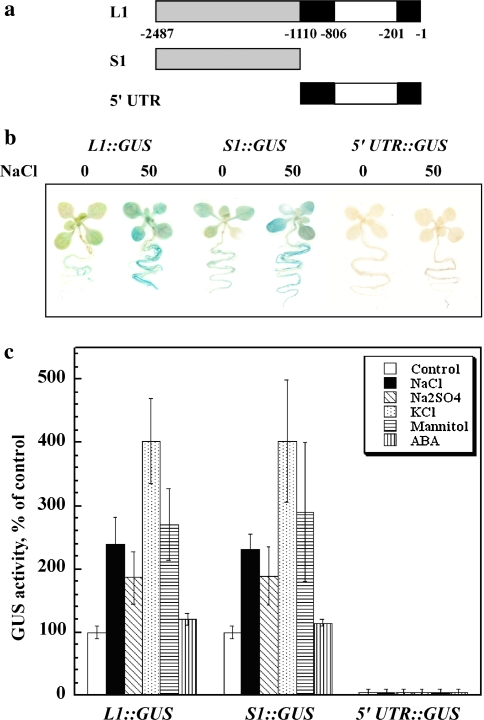

Fig. 2.

Expression of constructs containing BvNHX1 full-size promoter, promoter sequence upstream of the 5′ UTR, and 5′ UTR including intron. a Constructs used. Upstream promoter sequence, 5′ UTR, and intron are marked in gray, black and white, respectively. Nucleotides are numbered in according to the translation start ATG start sequence. b Histochemical staining of seedlings germinated and grown on solid medium without or with salt. Homozygous seeds of Arabidopsis transformed with the indicated constructs were sown on plates containing 0.5× MS solid medium (0) or the same medium supplemented with 50 mM NaCl (50). Two-week-old seedlings were stained for GUS. c Quantitative GUS expression in non-stressed and stressed Arabidopsis seedlings. GUS activity was assayed in homogenates of homozygous seedlings described in (b). Data shown represent average activity determined in homogenates prepared from 50 seedlings each of five independent lines of each constructs germinated and grown for 2 weeks on plates containing solid 0.5× MS medium without (white bars) or containing in addition 50 mM NaCl (black bars), 25 mM Na2SO4 (diagonally dashed), 50 mM KCl (dotted), 100 mM mannitol (horizontally dashed), or 20 μM ABA (vertically dashed). Activity is normalized to allow averaging between different transgenic lines and different experiments. GUS activities of L1::GUS and S1::GUS constructs under control conditions were similar, and were not statistically different

Interestingly, similar to DNA sequence encoding the 5′ UTR of the Arabidopsis AtNHX1, the 5′ UTR of BvNHX1 also contains an intron. To explore whether the 5′ UTR and intron play a role in the transcription regulation of the BvNHX1 gene, we transformed Arabidopsis plants with constructs in which the promoter sequence upstream of the transcription start (S1::GUS) or containing the 5′ UTR + intron (5′ UTR::GUS) were fused with GUS (Fig. 2a), and the plants were tested for GUS activity. GUS activities assayed in plants transformed with L1::GUS and S1::GUS were similar and differences were not statistically significant (not shown). The expression pattern of the S1::GUS lines, containing a 1,378 bp promoter sequence upstream of the transcription start, was indistinguishable to that of plants transformed with the L1::GUS construct both qualitatively (Fig. 2b) and quantitatively (Fig. 2c). On the other hand, the 5′ UTR::GUS construct had GUS activity similar to that of non-transformed control plants (Fig. 2b, c), suggesting that this sequence is not likely to affect the transcription of this gene.

Construction of serial deletions

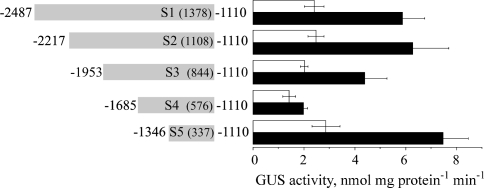

Five constructs comprising upstream sequences fused to reporter gene GUS were made. These constructs, designated S1::GUS to S5::GUS, contained 1,378, 1,108, 844, 576, and 337 bp promoter sequences upstream of the 5′ UTR. T2 and T3 generation plants from homozygous lines containing a single insertion were selected and at least five independent lines of each construct were tested. GUS activity in homogenates prepared from non-stressed and salt-treated seedlings was determined (Fig. 3). Deletions of 270 and 534 bp from the 5′ of the promoter sequence (S2 and S3, respectively) did not affect the promoter activity. Deletion of an additional 268 bp fragment inhibited the activation capacity of the resulting 567 bp promoter fragment (construct S4) both in the absence and presence of salt. On the other hand, the S5::GUS construct containing the shortest, 337 bp long, promoter fragment was sufficient to drive GUS expression to similar levels to that obtained by the S1::GUS construct both in the presence and absence of salt (Fig. 4). These results suggested that the transactivation capacity of the S5 promoter fragment was essentially identical to that of the full-length S1.

Fig. 3.

Serial deletion analysis of the BvNHX1 promoter activity. The 5′ serial deletions of the upstream promoter sequence (corresponding to the S1 sequence in Fig. 2) were fused to GUS and used to transform Arabidopsis. Nucleotides are numbered as in Fig. 2. GUS was assayed in homogenates prepared from 50 seedlings of each of five independent lines of each constructs, germinated and grown for 2 weeks on plates containing solid 0.5× MS medium without (white bars) or containing in addition 50 mM NaCl (black bars)

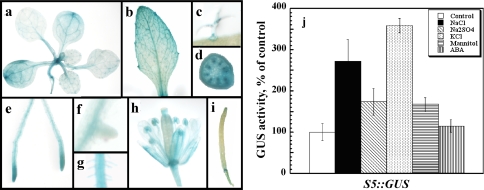

Fig. 4.

Activity of the 337 bp upstream promoter fragment. Homozygous plants expressing the S5 construct (Fig. 3, 337 bp promoter fragment fused to GUS) were assayed for the activity of the reporter gene. a–i Histochemical staining of non-stressed plants. a Shoot of soil grown plant. b Mature leaf of soil grown plant. c Trichome. d Cross-section of inflorescence stem. e Roots. f Emerging lateral root. g Root hairs. h Flower. i Silique. j Quantitative analysis using homogenates (five independent lines, 50 seedling each) from seedlings grown for 2 weeks in the 0.5× MS solid medium without (white bar) or containing in addition 50 mM NaCl (black bar), 25 mM Na2SO4 (diagonally dashed), 50 mM KCl (dotted), 100 mM mannitol (horizontally dashed), or 20 μM ABA (vertically dashed)

Analysis of potential cis-acting elements in the BvNHX1 minimal promoter region

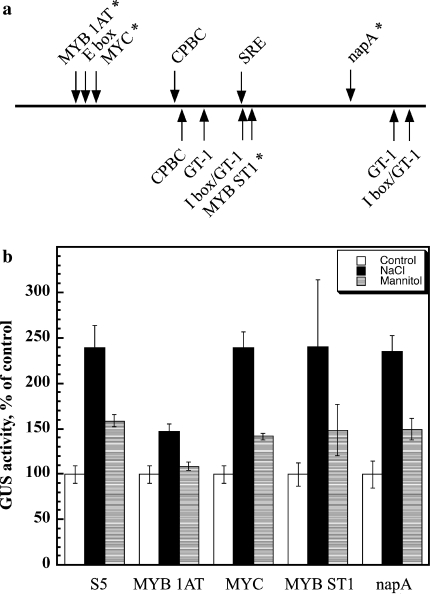

The DNA sequence of the S5 construct was used to search for potential binding sites of known trans-acting factors through the Plant cis-acting Regulatory DNA Elements (PLACE) database (Higo et al. 1999) http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/ (Fig. 5a). Four of these potential sites were further studied using site-directed mutagenesis (Table 1). The sequences are putative binding sites for MYB 1AT, MYC, MYB ST1, and napA transcription factors. Transcription factors from the MYC and MYB families are known to be also involved in the modulation of salt stress and water stress regulated genes (Zhu 2002; Shinozaki et al. 2003), whereas napA was shown to function in seeds (Stalberg et al. 1996). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using Stratagene QuikChange II®, where the putative cis-acting sequence was changed into a restriction enzyme recognition sequence (Table 1). Mutated sequences were confirmed by restriction digests and DNA sequence analyses, and were used for the genetic transformation of Arabidopsis plants. Homozygous transgenic plants were selected and assayed for GUS activity. The basal expression levels in non-stressed plants were not affected by the mutation of any of the potential cis-acting elements (Fig. 5b). Mutation in the MYB 1AT box (position −1362) almost abolished the induction of promoter activity by NaCl and mannitol, suggesting that the BvNHX1 promoter is regulated mainly by a MYB 1AT transcription factor. Other mutations did not affect the expression of the GUS reporter gene compared to the non-mutated S5 promoter fragment.

Fig. 5.

Activities of mutated 337 bp BvNHX1 promoter fragments. a Putative cis-acting elements in the S5 promoter fragment. Sites in forward or reverse modes are marked above and below the line, respectively. Mutated sequences are marked by asterisks. b GUS activity was assayed in homogenates made from five homozygous lines of Arabidopsis containing S5::GUS constructs with the indicated mutations (see also Table 1). Seeds were sowed on 0.5× MS (white bars) supplemented with 50 mM NaCl (black bars) or 100 mM mannitol (dashed bars), and seedlings harvested and analyzed 2 weeks later

Table 1.

Mutations of putative DNA binding sites of transcription factors

| Recognition | Location | Orientation | DNA sequence | Restriction site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | Mutated | ||||

| MYB 1AT | −1362 | + | ATAACCA | CTCGAGA | XhoI |

| MYC | −1358 | ± | CAATTG | TCTAGA | XbaI |

| MYB ST1 | −1228 | − | TATCCT | GGATCC | BamHI |

| napA | −1136 | + | CAAACAC | CCTCGAG | XhoI |

DNA sequences of putative DNA binding motifs (in bold) were mutagenized into a sequence containing restriction site (underlined)

To determine if the MYB 1AT box found in the heterologous A. thaliana species is also recognized in B. vulgaris, we challenged nuclear protein preparation extracted from salt-treated B. vulgaris seedlings for binding probes containing the WT or mutated MYB 1AT box. Figure 6 shows that B. vulgaris nuclear proteins bind WT MYB 1AT DNA sequence, but are incapable of binding the mutated sequence. Moreover, nuclear extract prepared from irrigated leaves did not show DNA binding activity under the conditions tested (Fig. 6) in agreement with Fig. 5.

Fig. 6.

B. vulgaris nuclear proteins bind WT but not mutated MYB 1AT DNA sequence. End-labeled dsDNA probes containing WT and mutated sequence were incubated with protein nuclear extract prepared from control or salt-treated B. vulgaris leaves. Mixes were resolved by native electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide, the gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film. Free and Bound, migration of the free and protein bound dsDNA probe, respectively

Discussion

NHX-like sodium/proton exchangers play important roles in establishing pH and ion homeostasis during salt stress (Pardo et al. 2006; Apse and Blumwald 2007). It has been suggested that an important difference between NHX genes from salt-sensitive and salt-tolerant plants is not in possible differences in the gene sequences but it resides in their expression patterns and the regulation of their expression. Similar to the Arabidopsis thaliana AtNHX1, BvNHX1 is expressed in leaves and roots and also in stamen, petal fruit bases and fruit tips (Shi and Zhu 2002). On the other hand, unlike AtNHX1, BvNHX1 is highly expressed in root tips and trichomes, but not in guard cells, at least in Arabidopsis (Fig. 1).

The 5′ UTR of BvNHX1 contains a 605 bp intron (Fig. 1a). Introns have been shown in some cases to increase transcriptional activity in plants (Rose 2004) in a process known as intron-dependent enhancement of transcription (IME) (Rose 2008). A recent bioinformatics study suggested that almost 20% of genomic sequences in Arabidopsis contain 5′ UTR introns (Chung et al. 2006). The BvNHX1 5′ UTR and its intron do not seem to affect the extent of gene expression, since their removal did not have any effect on the expression driven by 5′ upstream sequences in both the absence or presence of salt- and osmotic-stress (Fig. 2). Moreover, the DNA encoding the 5′ UTR and intron was not sufficient for driving expression (Fig. 2). Thus, the role of the BvNHX1 5′ UTR intron remains to be determined.

Activity assays of the 5′ deletion series of the BvNHX1 promoter suggested that nucleotides at positions −2487 to −1954 do not contain major cis-acting elements affecting gene expression (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the positions −1953 to −1686 and −1685 to −1347 might contain positive and negative elements, respectively (Fig. 3). Interestingly, a 347 bp promoter fragment (−1346 to −1110) could drive the expression of the GUS reporter gene (Figs. 3, 4) to similar levels to that of the full-length promoter sequence (Fig. 1, 2).

Bioinformatics analysis suggested a number of potential cis-acting elements occurring within this 347 bp promoter sequence (Fig. 5). Some of the proposed transcription factors are known to be regulated by salinity and drought. There are two binding sites for MYB transcription factors: the MYB 1AT binding site [consensus sequence (A/T)AACCA, TAACC in BvNHX1] in the promoters of dehydration-responsive gene rd22 and many other genes (Abe et al. 2003), and the MYB ST1 (Baranowskij et al. 1994), a MYB homolog containing only one repeat that can function as a transcriptional activator. The Myb motif of the MybSt1 protein (GGATA) is distinct from the plant Myb DNA binding domain described so far. MYC (consensus sequence CANNTG, CAATTG in BvNHX1) was shown to act in promoters of genes regulated by drought and cold stress (Abe et al. 2003; Chinnusamy et al. 2004; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2006). The napA element conserved in many seed-expressed genes (Stalberg et al. 1996). Interestingly the BvNHX1 promoter lacks a binding site for ABRE, a major transcription factor regulating genes modulated by salt and water stresses (Yamaguchi-Shinozaki and Shinozaki 2005). Mutating the MYB 1AT-binding site eliminated the salt and osmotic activation of the transcription activity of BvNHX1, whereas the other mutations did not affect its expression. EMSA assay using nuclear extract prepared from B. vulgaris leaves (Fig. 6) confirmed the results obtained with the heterologous A. thaliana plants (Fig. 5), e.g. DNA binding activity of the MYB 1AT sequence was induced by salt treatment, and was abolished when the DNA binding site was mutated. These results suggest that the mechanism is conserved between some sensitive and tolerant species. In vitro binding of the tobacco NtMYBJS1 to the AACC core motif was reduced by mutation of this sequence (Galis et al. 2006). The MYB family is the largest transcription factor family in plants with family size of up to 258 members, depending on the prediction algorithm used (Qu and Zhu 2006). The nature of the MYB protein(s) that modulate the activity of this gene is yet to be discovered. Nevertheless, this protein activity is not dependent on ABA. Expression analysis of 163 genes of the Arabidopsis MYB transcription factor family revealed that about 25% of them are affected by ABA (Yanhui et al. 2006).

The short promoter sequence identified here could be used as a water deficit-regulated promoter for driving gene expression in transgenic plants.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tao Xia for construction of the genomic library and the initial screen and Marina Large for technical help in preparation of DNA constructs and screening of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Research was supported by a grant from NSF-MCB-0343279. Dudy Bar-Zvi is the incumbent of The Israel and Bernard Nichunsky Chair in Desert Agriculture, Ben-Gurion University. Eduardo Blumwald is the incumbent of The Will Lester Endowed Chair in Pomology, University of California, Davis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- AtNHX1

Arabidopsis NHX1

- BvNHX1

Sugar beet NHX1

- EMSA

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- GUS

β-Glucoronidase

- MS

Murashige and Skoog basal plant medium

- MYB

Myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog

- MYC

Myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog

- NHX1

Sodium/proton exchanger 1

References

- Abe H, Urao T, Ito T, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2003;15:63–67. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharon GS, Apse MP, Duan SL, Hua XJ, Blumwald E. Characterization of a family of vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporters in Arabidopsisthaliana. Plant Soil. 2003;253:245–256. doi: 10.1023/A:1024577205697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Blumwald E. Na+ transport in plants. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2247–2254. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apse MP, Sottosanto JB, Blumwald E. Vacuolar cation/H+ exchange, ion homeostasis, and leaf development are altered in a T-DNA insertional mutant of AtNHX1, the Arabidopsis vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter. Plant J. 2003;36:229–239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranowskij N, Frohberg C, Prat S, Willmitzer L. A novel DNA-binding protein with homology to Myb oncoproteins containing only one repeat can function as a transcriptional activator. EMBO J. 1994;13:5383–5392. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkla BJ, Zingarelli L, Blumwald E, Smith JAC. Tonoplast Na+/H+ antiport activity and its energization by the vacuolar H+-ATPase in the halophytic plant Mesembryanthemumcrystallinum L. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:549–556. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.2.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E. Sodium transport and salt tolerance in plants. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:431–434. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E, Poole RJ. Na+/H+ antiport in isolated tonoplast vesicles from storage tissue of Betavulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:163–167. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E, Poole RJ. Salt tolerance in suspension cultures of sugar beet—induction of Na+/H+ antiport activity at the tonoplast by growth in salt. Plant Physiol. 1987;83:884–887. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.4.884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumwald E, Cragoe EJ, Poole RJ. Inhibition of Na+/H+ antiport activity in sugar beet tonoplast by analogs of amiloride. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:30–33. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert HJ, Gong QQ, Li PH, Ma SS. Unraveling abiotic stress tolerance mechanisms—getting genomics going. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan S, Forsthoefel N, Ran YQ, Quigley F, Nelson DE, Bohnert HJ. Na+/myo-inositol symporters and Na+/H+-antiport in Mesembryanthemumcrystallinum. Plant J. 2000;24:511–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQJ, Zhu T. Networks of transcription factors with roles in environmental stress response. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Schumaker K, Zhu JK. Molecular genetic perspectives on cross-talk and specificity in abiotic stress signalling in plants. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:225–236. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung BYW, Simons C, Firth AE, Brown CM, Hellens RP. Effect of 5′ UTR introns on gene expression in Arabidopsisthaliana. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsisthaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Yazaki Y, Ishikawa T, Koike S, Tanaka Y. Na+/H+ antiporter in tonoplast vesicles from rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Galis I, Simek P, Narisawa T, Sasaki M, Horiguchi T, Fukuda H, Matsuoka K. A novel R2R3 MYB transcription factor NtMYBJS1 is a methyl jasmonate-dependent regulator of phenylpropanoid-conjugate biosynthesis in tobacco. Plant J. 2006;46:573–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano GE, Pichersky E, Malik VS, Timko MP, Scolnik PA, Cashmore AR. An evolutionarily conserved protein binding sequence upstream of a plant light-regulated gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7089–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong QQ, Li PH, Ma SS, Rupassara SI, Bohnert HJ. Salinity stress adaptation competence in the extremophile Thellungiellahalophila in comparison with its relative Arabidopsisthaliana. Plant J. 2005;44:826–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada A, Shono M, Xia T, Ohta M, Hayashi Y, Tanaka A, Hayakawa T. Isolation and characterization of a Na+/H+ antiporter gene from the halophyte Atriplexgmelini. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;46:35–42. doi: 10.1023/A:1010603222673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA, Zhu JK, Bohnert HJ. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:463–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.51.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucl Acids Res. 1999;27:297–300. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson RA. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: the GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1987;5:387–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02667740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiu JJ, Zhang XJ, Lu CF. Characterization of the Na+/H+ antiporter in tonoplast vesicles from Populustremula calli. Prog Biochem Biophys. 2007;34:1303–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Kagami T, Suzuki M. Molecular and functional analysis of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene of Rosahybrida. Genes Genet Syst. 2005;80:121–128. doi: 10.1266/ggs.80.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munns R. Comparative physiology of salt and water stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:239–250. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoja O, Dainty J, Blumwald E. Tonoplast ion channels from sugar-beet cell-suspensions. Inhibition by amiloride and its analogs. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:1788–1794. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.4.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo JM, Cubero B, Leidi EO, Quintero FJ. Alkali cation exchangers: roles in cellular homeostasis and stress tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2006;57:1181–1199. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu LJ, Zhu YX. Transcription factor families in Arabidopsis: major progress and outstanding issues for future research—commentary. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:544–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AB. The effect of intron location on intron-mediated enhancement of gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004;40:744–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AB. Nuclear pre-mRNA processing in plants. Curr Topic Microbiol Immunol. 2008;326:227–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahi C, Singh A, Blumwald E, Grover A. Beyond osmolytes and transporters: novel plant salt-stress tolerance-related genes from transcriptional profiling data. Physiol Plant. 2006;127:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00610.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano R, Rodriguez-Navarro A. Ion homeostasis during salt stress in plants. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:399–404. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi HZ, Zhu JK. Regulation of expression of the vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene AtNHX1 by salt stress and abscisic acid. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;50:543–550. doi: 10.1023/A:1019859319617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Seki M. Regulatory network of gene expression in the drought and cold stress responses. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:410–417. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkolnik D, Bar-Zvi D. Tomato ASR1 abrogates the response to abscisic acid and glucose in Arabidopsis by competing with ABI4 for DNA binding. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:368–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottosanto JB, Saranga Y, Blumwald E. Impact of AtNHX1, a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter, upon gene expression during short-term and long-term salt stress in Arabidopsisthaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalberg K, Ellerstom M, Ezcurra I, Ablov S, Rask L. Disruption of an overlapping E-box/ABRE motif abolished high transcription of the napA storage-protein promoter in transgenic Brassicanapus seeds. Planta. 1996;199:515–519. doi: 10.1007/BF00195181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taji T, Seki M, Satou M, Sakurai T, Kobayashi M, Ishiyama K, Narusaka Y, Narusaka M, Zhu JK, Shinozaki K. Comparative genomics in salt tolerance between Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis-related halophyte salt cress using Arabidopsis microarray. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1697–1709. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasekina AV, Yershov PV, Reshetova OS, Tikhonova TV, Lunin VG, Trofimova MS, Babakov AV. Vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter from barley: Identification and response to salt stress. Biochem Mosc. 2005;70:100–107. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CE, Li Y, Labbe A, Guevara D, Nuin P, Whitty B, Diaz C, Golding GB, Gray GR, Weretilnyk EA, Griffith M, Moffatt BA. Transcriptional profiling implicates novel interactions between abiotic stress and hormonal responses in Thellungiella, a close relative of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;140:1437–1450. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.070508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CA, Yang GD, Meng QW, Zheng CC. The cotton GhNHX1 gene encoding a novel putative tonoplast Na+/H+ antiporter plays an important role in salt stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:600–607. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T, Apse MP, Aharon GS, Blumwald E. Identification and characterization of a NaCl-inducible vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter in Betavulgaris. Physiol Plant. 2002;116:206–212. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1160210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Blumwald E. Developing salt-tolerant crop plants: challenges and opportunities. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Fukada-Tanaka S, Inagaki Y, Saito N, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Tanaka Y, Kusumi T, Iida S. Genes encoding the vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger and flower coloration. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001;42:451–461. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:781–803. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang QC, Wu MS, Wang PQ, Kang JM, Zhou XL. Cloning and expression analysis of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene from Alfalfa. DNA Seq. 2005;16:352–357. doi: 10.1080/10425170500272742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanhui C, Xiaoyuan Y, Kun H, Meihua L, Jigang L, Zhaofeng G, Zhiqiang L, Yunfei Z, Xiaoxiao W, Xiaoming Q, Yunping S, Li Z, Xiaohui D, Jingchu L, Xing-Wang D, Zhangliang C, Hongya G, Li-Jia Q. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;60:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2910-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoi S, Quintero FJ, Cubero B, Ruiz MT, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM, Pardo JM. Differential expression and function of ArabidopsisthalianaNHX Na+/H+ antiporters in the salt stress response. Plant J. 2002;30:529–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GH, Su Q, An LJ, Wu S. Characterization and expression of a vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene from the monocot halophyte Aeluropuslittoralis. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Plant salt tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6:66–71. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53:247–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2003;6:441–445. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]