Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effects of selective progesterone receptor modulator CDB4124 on cell proliferation and apoptosis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma smooth muscle (LSM) cells and control myometrial smooth muscle (MSM) cells in matched uteri.

Design

Laboratory research.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Patient(s)

Premenopausal women (n=12) undergoing hysterectomy for leiomyoma-related symptoms.

Intervention(s)

Treatment of primary LSM and MSM cells with CDB4124 (10-8-10-6M) or vehicle for 24, 48 or 72 hours.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Western blot for protein expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), cleaved poly-adenosine 5’-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP), Bcl-2 and Krüppel-like transcription factor 11 (KLF11); MTT assay to evaluate viable cell numbers; and real-time polymerase chain reaction to quantify mRNA levels.

Result(s)

Treatment with CDB4124 significantly decreased levels of the proliferation marker PCNA, the number of viable LSM cells, and the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2. On the other hand, treatment with CDB4124 increased levels of the apoptosis marker cleaved PARP and the tumor suppressor KLF11 in a dose- and time-dependent manner in LSM cells. In matched MSM cells, however, CDB4124 did not affect cell proliferation or apoptosis.

Conclusion(s)

CDB4124 selectively inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in LSM but not in MSM cells.

Keywords: uterine leiomyoma, myometrium, antiprogestin, proliferation, apoptosis, PCNA, PARP, Bcl-2

INTRODUCTION

Uterine leiomyoma (fibroids) are the most common tumors in women of reproductive age. They are symptomatic in 50% of cases, with the peak incidence of symptoms occurring among women in their 30s and 40s (1). Symptoms include irregular uterine bleeding, pressure symptoms such as increased urinary frequency and constipation; and they may interfere with reproduction. Symptoms associated with fibroids usually resolve with the onset of menopause, suggesting that these tumors are dependent on ovarian steroids (2). Thus, although benign, fibroids have a major impact on women’s health and their quality of life. Uterine fibroids are the single most underlying indication for hysterectomy (3). However, given the choice, many women would opt to avoid surgery. There is clearly a need for medical therapy that eliminates the need for surgery. Currently, there is no effective long-term medication for the treatment of uterine fibroids, but research is ongoing and promising avenues are being developed (4).

Although the etiology of uterine fibroids is unknown, antiprogestins have considerable potential in treatment of leiomyoma. Mifepristone is the first progesterone antagonist, which showed high affinity binding to the progesterone receptor (PR) (5-9). Clinical trials have shown that mifepristone led to a shrinkage of fibroids dependent on dose and duration of treatment and resulted in the relief of symptoms (10).

Other antiprogestins have been synthesized and tested in an attempt to identify relatively pure progesterone antagonists with little or no antiglucocorticoid activity, such as CDB2914 and CDB4124 (Proellex™)(11, 12). The 21-substituted 19-norprogestin, CDB4124, was developed as an antiprogestin for several gynecological indications, such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Previous studies suggested that CDB4124 lacks any estrogenic, androgenic, antiestrogenic, and antiandrogenic activity. CDB4124 was also suggested to be a potent antiprogestin with less antiglucocorticoid activity compared with mifepristone (7, 13-15). CDB4124 has been tested in clinical trials for treatment of hormone dependent diseases such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids. The manufacturer Repros Therapeutics announced on August 3, 2009 that it is voluntarily suspending all clinical trials of CDB4124 because of significant increases in liver enzymes associated with the drug use (16).

The precise mechanism underlying the beneficial action of CDB4124 on uterine leiomyoma remains to be elucidated. In the present study, we evaluated the effects of CDB4124 on the proliferation and apoptosis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma smooth muscle (LSM) cells and control myometrial smooth muscle (MSM) cells from matched uteri.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Collection and Primary Cell Culture

Human uterine leiomyoma and matched myometrial tissues were obtained at surgery from 12 women (mean age 40 years, range 33-48) undergoing hysterectomy at the Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago, IL for symptomatic leiomyoma. All of the subjects gave written informed consent for the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. The size of the tumors ranged from 3.5 to 15 cm in diameter. The subjects had not received any hormonal treatment for at least 3 months before surgery, and each uterine specimen was evaluated histologically by a pathologist. Six samples were obtained during the follicular phase, 4 during the luteal phase and 2 during menstruation. We isolated LSM cells from a peripheral portion at 1 cm to the outer capsule of a leiomyoma and isolated matched MSM cells from the adjacent myometrial tissue at 2 cm from a leiomyoma, and cultured them as previously described with minor modifications (17). Primary cells were used in first passage to minimize possible changes in phenotype and gene expression.

Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 1:1 (GIBCO/BRL, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The monolayer cultures, at approximately 70% confluency, were starved in serum-free medium overnight and then treated with CDB4124. Cells were incubated in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 medium 1:1 containing 1% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum with different concentrations of CDB4124 (10-8, 10-7 and 10-6M) for 24, 48, or 72 h. CDB4124 was dissolved in absolute ethyl alcohol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the same concentration of ethyl alcohol (1:1000) was used as a vehicle in control cultures.

Protein Isolation and Immunoblotting

Cultured LSM and MSM cells were lysed using Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (M-PER; Pierce, Rockford, IL) and 1× protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentrations were determined by colorimetric BCA protein Assay (Pierce), and equal amount total protein were loaded in each well. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Membranes were probed using antibodies against β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), human proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA, Millipore, Burlington, MA), Bcl-2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverley, MA), cleaved poly adenosine 5’-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP, Cell Signaling Technology) or KLF11 (Novus, Littleton, CO). Anti-mouse and anti-goat IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology) were used as secondary antibodies. Lastly, immunoreactive bands were visualized using an ECL-detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

Cell Viability Assay

The effects of CDB4124 on the viability of LSM and MSM cells were evaluated by Vybrant® MTT cell proliferation assay kit (V-13154) (Invitrogen). The cells were cultured to 70% confluence in a 96-well culture plate and starved in serum-free medium overnight. Then cells were treated with vehicle (ethyl alcohol 1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich) or various concentrations of CDB4124 (10−8, 10−7 and 10−6M) in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 with 1% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum for 72 h, and the MTT assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA Preparation and Real-time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from LSM and MSM cells was extracted using Tri-reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). Complementary DNA was prepared with qScript™ cDNA SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) from 1.5 micrograms of RNA. Primers against Bcl-2 were purchased from QIAGEN (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Specific oligodeoxynucleotide primers for KLF11 were synthesized based on its published cDNA sequence (F: 5’-CCATTCTTTATCGACTCTGTGC -3’; R: 5’-GCAGAGGACTGGAGAACATC -3’). Primers against the constitutively expressed glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as described in previous reports (18). Primer specificity was confirmed by single peaks demonstrated using dissociation curves after amplification of cDNA.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to determine the relative amounts of each transcript using the DNA-binding dye SYBR green (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the ABI Prism 7900HT Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions started at 50°C for 2 min followed by 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. The cycle threshold (Ct) was placed at a set level where the exponential increase in PCR amplification was approximately parallel between all samples. Relative fold change was calculated by comparing Ct values between the target gene and GAPDH as the reference guide. The 2-ΔΔCt method was used to analyze these relative changes in gene expression (19).

Statistical Analysis

The data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance followed by Fisher’s protected least significance difference test. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of CDB4124 on Proliferation in LSM and MSM Cells

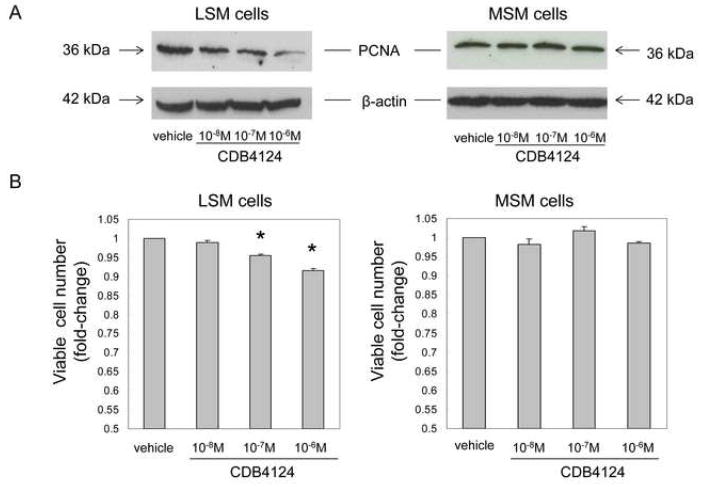

We treated primary LSM and MSM cells with graded concentrations of CDB4124 for 24, 48 or 72 h, and determined protein levels of the proliferation marker named proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) using western blot analysis. At 24 h, no changes were noted in PCNA levels in either cell type (data not shown). At 48 h, only 10-6M CDB4124 decreased PCNA in LSM but not in MSM cells (data not shown). At 72 h, however, CDB4124 reduced PCNA levels in LSM cells in a dose (10-8-10-6M)-dependent manner (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Effects of CDB4124 on PCNA expression in LSM and MSM cells by western blot analysis. Blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody as a loading control. Data were presented from one representative subject. Results were reproduced in cells from two other subjects. (B) Effects of CDB4124 on the number of viable LSM and MSM cells, as assessed by MTT assay. Data were reported as the mean ± SEM using cells from three subjects. Each count was performed using cells cultured in triplicate wells. * P < 0.05 vs. vehicle treatment.

Alterations in primary LSM and MSM cell proliferation after treatment with CDB4124 for 72 h were verified by an MTT assay. As shown in Figure 1B, CDB4124 reduced LSM cell viability significantly in a dose-dependent manner. CDB4124 did not affect viability of MSM cells at any time point or concentration. Each western or MTT experiment was reproduced in matched LSM and MSM cells from 3 different subjects.

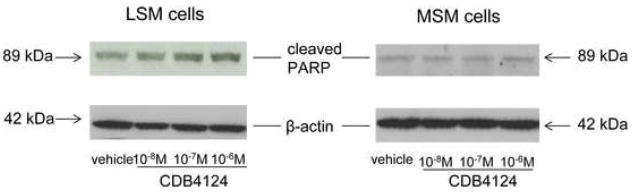

Effects of CDB4124 on Cleaved PARP Expression in LSM and MSM Cells

Cleaved PARP expression is a marker of cells undergoing apoptosis. To check whether CDB4124 differentially regulates apoptosis in primary LSM and MSM cells, cleaved PARP levels were determined after CDB4124 treatment. As shown in Figure 2, treatment with CDB4124 for 72 h increased cleaved PARP levels in a dose-dependent manner in LSM cells but not in normal MSM cells. This result was reproduced in matched LSM and MSM cells from two other subjects and indicates that CDB4124 selectively induced apoptosis of LSM cells.

FIGURE 2.

Effects of CDB4124 on cleaved PARP protein expression in LSM and MSM cells. Cleaved PARP protein expression was determined by western blotting. Equal loading was confirmed by immunoblotting with a β-actin antibody. Data were presented from one representative subject. Results were reproduced using cells from two other subjects.

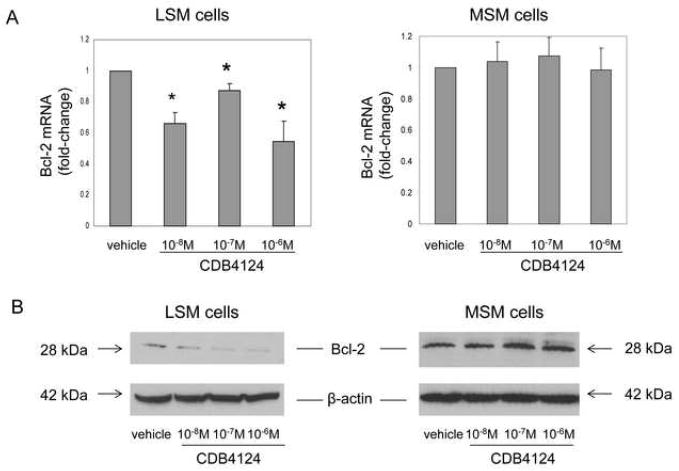

Regulation of Bcl-2 Expression by CDB4124 in LSM and MSM Cells

We and others previously showed that progesterone up-regulated the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 in LSM cells (20, 21). Thus, we hypothesized that CDB4124 could induce LSM cell apoptosis through down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression. To test this possibility, the effects of CDB4124 on Bcl-2 mRNA expression in primary LSM and MSM cells were assessed by real-time PCR at 24 or 48 h; and the effects on Bcl-2 protein expression were measured by western blot analysis at 72 h. Treatment with 10-8-10-6M CDB4124 for 48 h significantly reduced Bcl-2 mRNA levels in LSM but not in MSM cells (Fig. 3A). Shorter treatment (24 h) decreased Bcl-2 mRNA levels in LSM but not in MSM cells only at 10-6 M concentration (data not shown). Treatment with CDB4124 for 72 h markedly decreased Bcl-2 protein expression in LSM cells; its expression, however, was not affected in MSM cells (Fig. 3B). In summary, CDB4124 decreased Bcl-2 expression in LSM but not in MSM cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Experiments in Figure 3 are representative of findings using matched LSM and MSM cells from 3 different subjects.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Effects of CDB4124 on Bcl-2 mRNA levels in LSM and MSM cells. Data were shown as the mean ± SEM from one representative experiment. Each experiment was performed using cells in triplicate wells and repeated in two other subjects. * P < 0.05 vs. vehicle treatment. (B) Effects of CDB4124 on Bcl-2 protein levels in LSM and MSM cells. Blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody as a loading control. Data shown were from one representative experiment and reproduced using cells from a total of three subjects.

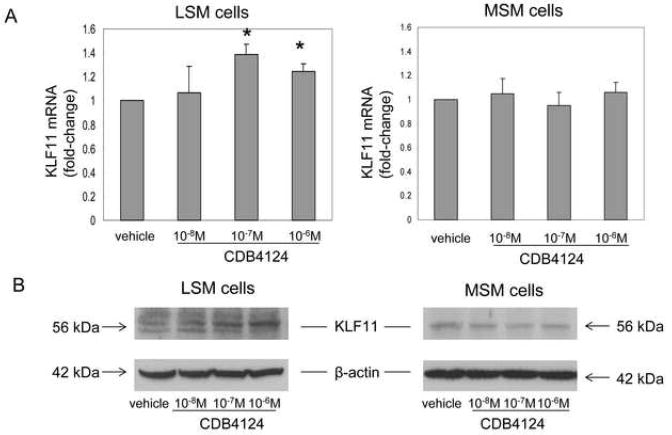

Regulation of KLF11 Expression by CDB4124 in LSM and MSM Cells

KLF11 is a tumor suppressor. We checked whether CDB4124 differentially regulates KLF11 expression in LSM or MSM cells. As Figure 4A shows, KLF11 mRNA levels in LSM cells were significantly induced by treatment with CDB4124 for 48 h. In contrast, this treatment did not change KLF11 expression in MSM cells. Treatment with 10-6M CDB4124 for 24 h also increased KLF11 mRNA expression in LSM cells but not in MSM cells (data not shown). Treatment with CDB4124 for 72 h markedly increased KLF11 protein expression in LSM but not in MSM cells (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that CDB4124 induced the expression of the tumor-suppressor KLF11 in LSM but not in MSM cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner. Figure 4 illustrates representative experiments reproduced in matched cells from two other subjects.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Regulation of CDB4124 on KLF11 mRNA expression in LSM and MSM cells. Data were shown as the mean ± SEM from one representative experiment. Each experiment was done in triplicate wells and repeated using cells from two other subjects. * P < 0.05 vs. vehicle treatment. (B) Regulation of CDB4124 on KLF11 protein levels in LSM and MSM cells. Blots were reprobed with a β-actin antibody as a loading control. Data shown were from one representative experiment and reproduced using cells from a total of three subjects.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated that CDB4124 exerts remarkable and selective growth inhibitory effects on primary LSM cells by decreasing proliferation and increasing apoptosis, but it does not affect these key biologic end-points in MSM cells. CDB4124 has been shown to be a potent antiprogestin in a variety of in vivo and in vitro assays (15). Progesterone antagonists are capable of binding to progesterone receptors, and cause conformational changes that are distinct from those caused by progesterone agonists (22, 23). According to a previous report, progesterone antagonists modify the ability of receptors to interact with co-activators or co-repressors (24). Co-activators and co-repressors are nuclear proteins that modulate the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors. Co-activators enhance the transcriptional activity of nuclear receptors, whereas co-repressors elicit inhibitory effects on nuclear receptors (25). Thus, the properties of CDB4124 to oppose progesterone action with respect to possible co-repressor or co-activator recruitment to key target gene promoters in LSM cells remain to be elucidated.

In our study, CDB4124 induced apoptosis of LSM cells in a dose-dependent manner through up-regulating cleaved PARP expression and down-regulating Bcl-2 protein expression. The cleavage of PARP is regarded as a hallmark event for the apoptotic paradigm (26). Bcl-2, which has anti-apoptotic properties, is associated with the outer mitochondrial membrane. Bcl-2 stabilizes membrane permeability, thereby preserving mitochondrial integrity, suppressing the release of cytochrome c and inhibiting apoptosis (27). Our results suggest that CDB4124 may act to trigger an intrinsic mitochondria-mediated apoptotic pathway by down-regulating Bcl-2 expression and increased PARP expression.

KLF11 is a tumor suppressor, which was initially reported to be a transcription factor and a downstream effector of TGF-β dependent signaling (28). Although the mechanism involved in KLF11-regulated cell proliferation needs to be further clarified, it is down-regulated in human cancers, inhibits cell growth in vitro and in vivo, and inhibits neoplastic transformation (28). Our results indicate that CDB4124 inhibits LSM cell proliferation at least in part through up-regulation of KLF11.

The pharmacokinetic studies showed that subjects who received 200 mg of CDB4124 daily, maintained blood levels of approximately 1.6-4.2 × 10-6M of this drug (29). Therefore, 10-8-10-6M concentrations, used in our experiments were within or below this range. Unlike LSM cells, CDB4124 did not affect the growth and survival of MSM cells. The precise mechanisms underlying the differential effects of CDB4124 in LSM and MSM cells remain to be determined. The differential responses to CDB4124 in LSM vs. MSM cells might be due to higher levels of PR in leiomyoma vs. myometrial tissues and cells or differential availability and functions of co-activators and co-repressors and their recruitment to key promoters in these cell types (18, 30-33).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the antiprogestin CDB4124 selectively inhibits the proliferation and induces apoptosis of human LSM cells without affecting the proliferation or apoptosis in MSM cells. Our observations regarding the differential effects of CDB4124 on leiomyoma vs. myometrial cells are consistent with the previous publications on CDB2914 (32, 33). Also, it was demonstrated that other antiprogestins, such as RU486 and asoprisnil, inhibit leiomyoma cell survival (34-36). Thus, our current findings lend further credence to the notion that antiprogestins as a class of compounds may act through a common mechanism to suppress fibroid growth and exert their therapeutic effects.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01-057877. Dr. Bulun received consultant fees from Repros Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wise LA, Palmer JR, Stewart EA, Rosenberg L. Age-specific incidence rates for self-reported uterine leiomyomata in the Black Women’s Health Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:563–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154161.03418.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh EE, Bulun SE. Steroid hormones and leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilcox LS, Koonin LM, Pokras R, Strauss LT, Xia Z, Peterson HB. Hysterectomy in the United States, 1988-1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:549–55. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankaran S, Manyonda IT. Medical management of fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22:655–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadepond F, Ulmann A, Baulieu EE. RU486 (mifepristone): mechanisms of action and clinical uses. Annu Rev Med. 1997;48:129–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kloosterboer HJ, Deckers GH, van der Heuvel MJ, Loozen HJ. Screening of anti-progestagens by receptor studies and bioassays. J Steroid Biochem. 1988;31:567–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neef G, Beier S, Elger W, Henderson D, Wiechert R. New steroids with antiprogestational and antiglucocorticoid activities. Steroids. 1984;44:349–72. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(84)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitz IM, Croxatto HB, Robbins A. Antiprogestins: mechanism of action and contraceptive potential. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:47–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teutsch G, Philibert D. History and perspectives of antiprogestins from the chemist’s point of view. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(Suppl 1):12–31. doi: 10.1093/humrep/9.suppl_1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinauer J, Pritts EA, Jackson R, Jacoby AF. Systematic review of mifepristone for the treatment of uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:1331–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000127622.63269.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benagiano G, Bastianelli C, Farris M. Selective progesterone receptor modulators 3: use in oncology, endocrinology and psychiatry. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:2487–96. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.14.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levens ED, Potlog-Nahari C, Armstrong AY, Wesley R, Premkumar A, Blithe DL, et al. CDB-2914 for uterine leiomyomata treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1129–36. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181705d0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busso N, Collart M, Vassalli JD, Belin D. Antagonist effect of RU 486 on transcription of glucocorticoid-regulated genes. Exp Cell Res. 1987;173:425–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90282-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gagne D, Pons M, Crastes de Paulet A. Analysis of the relation between receptor binding affinity and antagonist efficacy of antiglucocorticoids. J Steroid Biochem. 1986;25:315–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(86)90242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attardi BJ, Burgenson J, Hild SA, Reel JR, Blye RP. CDB-4124 and its putative monodemethylated metabolite, CDB-4453, are potent antiprogestins with reduced antiglucocorticoid activity: in vitro comparison to mifepristone and CDB-2914. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;188:111–23. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.reprosrx.com/proellex.html.

- 17.Rossi MJ, Chegini N, Masterson BJ. Presence of epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, and their receptors in human myometrial tissue and smooth muscle cells: their action in smooth muscle cells in vitro. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1716–27. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.3.1311246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa H, Reierstad S, Demura M, Rademaker AW, Kasai T, Inoue M, et al. High aromatase expression in uterine leiomyoma tissues of African-American women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1752–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yin P, Lin Z, Cheng YH, Marsh EE, Utsunomiya H, Ishikawa H, et al. Progesterone receptor regulates Bcl-2 gene expression through direct binding to its promoter region in uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4459–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuo H, Maruo T, Samoto T. Increased expression of Bcl-2 protein in human uterine leiomyoma and its up-regulation by progesterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:293–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.1.3650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein-Hitpass L, Cato AC, Henderson D, Ryffel GU. Two types of antiprogestins identified by their differential action in transcriptionally active extracts from T47D cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1227–34. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spitz IM. Progesterone antagonists and progesterone receptor modulators: an overview. Steroids. 2003;68:981–93. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitz IM, Chwalisz K. Progesterone receptor modulators and progesterone antagonists in women’s health. Steroids. 2000;65:807–15. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chwalisz K, Perez MC, Demanno D, Winkel C, Schubert G, Elger W. Selective progesterone receptor modulator development and use in the treatment of leiomyomata and endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:423–38. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pieper AA, Verma A, Zhang J, Snyder SH. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, nitric oxide and cell death. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:171–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jang JH, Surh YJ. Bcl-2 protects against Abeta(25-35)-induced oxidative PC12 cell death by potentiation of antioxidant capacity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:880–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez-Zapico ME, Mladek A, Ellenrieder V, Folch-Puy E, Miller L, Urrutia R. An mSin3A interaction domain links the transcriptional activity of KLF11 with its role in growth regulation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4748–58. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.http://www.drugs.com/clinical_trials/repros-therapeutics-inc-announces-proellex-shows-no-adverse-cardiac-pilot-trial-4237.html.

- 30.Englund K, Blanck A, Gustavsson I, Lundkvist U, Sjoblom P, Norgren A, et al. Sex steroid receptors in human myometrium and fibroids: changes during the menstrual cycle and gonadotropin-releasing hormone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4092–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.11.5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo X, Yin P, Reierstad S, Ishikawa H, Lin Z, Pavone ME, et al. Progesterone and Mifepristone Regulate L-Type Amino Acid Transporter 2 and 4F2 Heavy Chain Expression in Uterine Leiomyoma Cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Q, Ohara N, Chen W, Liu J, Sasaki H, Morikawa A, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 down-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor, adrenomedullin and their receptors and modulates progesterone receptor content in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2408–16. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Q, Ohara N, Liu J, Amano M, Sitruk-Ware R, Yoshida S, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 induces extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:181–91. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morikawa A, Ohara N, Xu Q, Nakabayashi K, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, et al. Selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil down-regulates collagen synthesis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells through up-regulating extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:944–51. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohara N, Morikawa A, Chen W, Wang J, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, et al. Comparative effects of SPRM asoprisnil (J867) on proliferation, apoptosis, and the expression of growth factors in cultured uterine leiomyoma cells and normal myometrial cells. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:20–7. doi: 10.1177/1933719107311464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki H, Ohara N, Xu Q, Wang J, DeManno DA, Chwalisz K, et al. A novel selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil activates tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-mediated signaling pathway in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells in the absence of comparable effects on myometrial cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:616–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]