Abstract

Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells (OHCs) with the unique capability of performing direct, rapid and reciprocal electromechanical conversion. Prestin consists of 744 amino acids with a molecular mass of ~81.4 kDa. The predicted membrane topology and molecular mass of a single prestin molecule appear inadequate to account for the size of intramembrane particles (IMPs) expressed in the OHC membrane. Although recent biochemical evidence suggests that prestin forms homo-oligomers, most likely as a tetramer, the oligomeric structure of prestin in OHCs remains unclear. We obtained the charge density of prestin in the gerbil OHCs by measuring their nonlinear capacitance (NLC). The average charge density (22,608 μm−2) measured was four times the average IMP density (5,686 μm−2) reported in the freeze-fracture study. This suggests that each IMP contains four prestin molecules, based on the general notion that each prestin transfers a single elementary charge. We subsequently compared the voltage dependency and the values of slope factor of NLC and somatic motility simultaneously measured from the same OHCs to determine whether NLC and motility are fully coupled and how prestin subunits function within the tetramer. We showed that the voltage dependency and slope factors of NLC and motility were not statistically different, suggesting that NLC and motility are fully coupled. The fact that the slope factor is the same between NLC and motility suggests that each prestin monomer in the tetramer is in parallel, each interacting independently with cytoplasmic or other partners to facilitate the mechanical response.

Keywords: prestin, oligomer, outer hair cell, electromotility, nonlinear capacitance, cochlear mechanics

INTRODUCTION

The outer hair cell is one of two receptor cells in the organ of Corti, and plays a critical role in mammalian hearing. OHCs are able to rapidly change their length (Brownell et al., 1985; Kachar et al., 1986) and stiffness (He and Dallos, 1999) when their membrane potential is altered. Morphological studies show that OHC membrane contains large protein particles (~12 nm in diameter) with the packing density exceeding 5,000 μm−2 (Forge, 1991). Correlation between the development of motility (He et al., 1994) and particle density in developing OHCs (Souter et al., 1995) suggests that the majority of the intramembrane particles (IMPs) are the motor protein which drives the length and stiffness changes (He et al., 2009). The motor protein named prestin has been identified (Zheng et al., 2000). Prestin has 744 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 81.4 kDa. The predicted amino-acid sequence and molecular mass of prestin monomer appear to be inadequate to account for the size of IMPs in the membrane. Some biochemical studies suggest that prestin forms homo-oligomer, possibly as a tetramer (Zheng et al., 2006; Mio et al., 2008), while another study shows that prestin forms dimmers (Detro-Dassen et al., 2007). Therefore, it is still not clear whether prestin forms tetramers, trimers, or dimmers.

Associated with OHC electromotility is an electrical signature, a voltage-dependent capacitance or, correspondingly, a gating charge movement (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991). Measures of the gating currents have been used in estimating the density of ion channels in a membrane (Hille, 1992). To determine whether prestin forms oligomers in the plasma membrane, we attempted to calculate the charge density of prestin by measuring prestin-associated charge movement in gerbil OHCs. The reason that we chose to measure charge density from gerbil OHCs is that the IMP density in the lateral membrane of gerbil OHCs has been determined using the freeze fracture and electron microscopy (Forge, 1991; Souter et al., 1995; Köpple et al., 2004). Comparison of the charge density with the IMP density in the same species would allow us to estimate how many prestin molecules constitute each 12-nm IMP in the membrane.

The function of mammalian prestin is generally defined by two essential electrophysiological properties: a voltage sensor that detects changes in the transmembrane potential of the cell and the actuator that undergoes a conformational change that results in somatic motility (Dallos and Fakler, 2002; Ashmore, 2008). The voltage sensor is manifested as nonlinear capacitance (NLC) while the actuator is reflected by somatic motility. There is a strong intimation in the literature that NLC and motility are essentially interchangeable measures reflecting the motor function of OHCs (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Ashmore, 2008). The experimental evidence, however, is sparse. We measured NLC and somatic motility simultaneously from gerbil OHCs to determine whether NLC and motility were indeed interchangeable measures. A more interesting question was whether the prestin monomers making up each IMP operate as one integrated motor unit or whether each monomer in the oligomer functions independently. If the mechanical response of each subunit in the oligomer is independent as each monomer is in parallel to each other, the slope of the motility function should be the same as that of the capacitance function. If, however, the monomers are required to form one single motor unit as monomers are in series, the length vs. voltage function should have steeper slope (4-times steeper if it is a tetramer). Therefore, comparison of the slope of NLC and motility would allow us to address this issue.

RESULTS

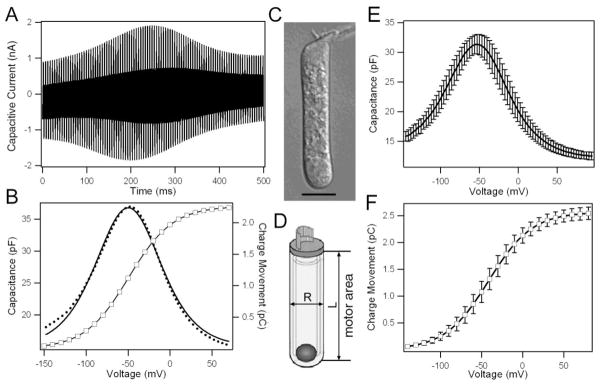

1. Prestin Forms Tetramer in the Plasma Membrane of OHCs

To determine charge density of prestin, we measured gating current from the gerbil OHCs in response to a 500-ms long voltage ramp ranging from −150 mV to 70 mV in 4 mV increment. Superimposed on the ramp were two sinusoids (10 mV in amplitude) with frequencies of 390.6 and 781.2 Hz. The voltage protocol and the subsequent fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis allowed us to obtain motility-related gating charge movement and the corresponding NLC (Santos-Sacchi et al., 1998). Fig. 1A shows an example of the voltage-evoked capacitive current obtained from an apical turn OHC whose image is shown in Fig. 1C. The capacitive current exhibited the peak response in the middle of the waveform with the response magnitude decreased in both ends as the membrane potential varied from −150 to 70 mV. We extracted the total charge movement from the capacitive response. As shown in Fig. 1B, the charge movement exhibited a sigmoid voltage-dependent relation (Q-V function, represented by open squares) with maximum charge movement reaching 2.3 pC. NLC was the derivative of the charge movement with respect to voltage, and thus had a bell-shaped dependence on the membrane potential (Fig. 1B) with peak capacitance near −50 mV. We measured 14 OHCs that have the largest NLC for analysis from the apical turn. The means and standard deviations (SDs) of NLC and Q-V function are exhibited in Figs. 1E and F, respectively. We computed five parameters from these cells. These parameters include: the maximum charge displacement (Qmax) the slope (α), the voltage at peak capacitance (V1/2), the NLC (Cnon-lin), and the linear capacitance (Clin). The means of Qmax and z derived from curve fitting of the NLC are 2.5 ± 0.2 pC and 0.8 ± 0.04, respectively, with the Qmax corresponding to 1.5 ± 0.1 × 107 elementary charges (1 C = 6.24 × 1018 elementary charges). The valence, z, is less than one, implying that one charge is transferred per prestin molecule (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Ashmore, 2008).

Figure 1.

A. Example of capacitive currents measured from the OHC shown in C. B. NLC and charge movement as a function of voltage. NLC (dotted lines) were fitted with the derivative of a first-order Boltzmann function (solid line). C. Micrograph of an apical turn gerbil OHC. The computed five parameters obtained from curve fitting are: Qmax: 2263 fC, α: 26.3 mV, V1/2: −49.3 mV, Clin: 15 pF. D. Schematic drawing of an OHC to show how the total surface area containing prestin is calculated. E. Means and SDs of the voltage-dependence of NLC from 14 cells. F: Means and SDs of the voltage-dependence of total charge movements.

In order to calculate the charge density, we subsequently measured the total surface area of the lateral membrane from the cells from which the NLC data were acquired. OHCs are cylindrical and their surface area can be calculated as: As=πRL, with R being the diameter, and L, the length of the cell. The length of lateral membrane was measured from 2 μm below the cuticular plate to the plane of the end of the nucleus, whereas the cell’s diameter was measured in the midpoint of the cell (Fig. 1D). The reason to adopt such criteria is that the motor protein is not expressed in the ~ 2- μm tight-adherence apical junctional belt (Nunes et al., 2006). Dallos et al. (1991) and Huang and Santos-Sacchi (1993) showed that motility or NLC is not present in the membrane of synaptic pole below the top of the nucleus. With this adopted criteria, the average length and diameter are 37.8 ± 3.4 and 7.7 ± 0.3 μm, respectively. Therefore, the total area of the lateral membrane containing prestin is 910 ± 89 μm2. The total elementary charge density after correcting Qmax for z is 22,608 ± 1,525 μm− 2 (1C = 6.24 × 1018 elementary charges).

It is generally believed that each prestin molecule transfers a single elementary charge (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Dallos and Fakler, 2002). Therefore, the total charge can be considered equal to the total number of prestin molecules expressed in an OHC. Thus, the total charge density would represent the total amount of prestin molecules in the lateral membrane of OHCs. If we divided the total charge density per square micro by the IMP density obtained from freeze fracture count in gerbil OHCs, the results would reflect the number of prestin molecules contained in each IMP. It has been reported that the average IMP density in the adult gerbil OHCs is 5,686 particles μm− 2 (Köpple et al., 2004). Based on this number, the mean value of the number of prestin molecules in each IMP is estimated to be 4.0 ± 0.3. This value is not statistically different from the mean value of 4 (One-sample t test, P = 0.50) for a tetramer, suggesting that each IMP contains four prestin molecules.

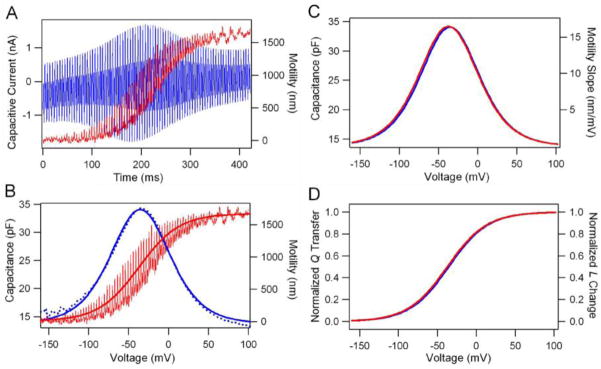

2. Each Prestin Molecule in the Tetramer Is Mechanically Independent

There is a strong intimation in the literature that NLC and motility are essentially interchangeable measures (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Ashmore, 2008). We measured NLC and motility simultaneously from gerbil OHCs to determine whether NLC and motility were indeed fully coupled. The comparison of the two responses would also allow us to determine whether each prestin subunit in the tetramer is independently operated or whether the 4 subunits form one mechanical unit. We used the same voltage protocol described above to elicit electromotility and motility-related charge movement. The resultant capacitive current and motility responses, simultaneously recorded from an apical turn gerbil OHC, are shown in Fig. 2A. The capacitive current response (in blue) had a peak response in the middle of the waveform as the membrane voltage stepped from −150 to 70 mV. In response to the ramp voltage commands, the motile response (in red) showed a sigmoid shape with saturation in the ends of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing directions. Superimposed on the sigmoid-shaped response was the cycle-by-cycle, or AC motility component, which was evoked by the AC signals (390.6 and 781.2) in the stimuli. The magnitude of the AC motility also depended on the voltage. The AC response was small in both ends where the motile response was already saturated. The maximum AC response was seen in the middle of the sigmoid curve where the slope was the steepest. In Fig. 2B, motility (in red) and NLC (in blue) are plotted as a function of voltage. The motile response was fit by the two-state Boltzmann function. The motility sensitivity (Fig. 2C) was obtained by differentiating the fitting values. The NLC was described as the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function and had a bell shape as a function of voltage (Fig. 2B and C). As shown, the two bell-shaped curves had similar slopes (Fig. 2C). In Fig. 2D, the normalized charge transferred and length change are plotted as a function of voltage. It is apparent that the two curves overlapped.

Figure 2.

Simultaneous measurements of motility and gating currents associated with prestin from a 40 μm gerbil OHC. A. Capacitive currents (blue) and motility (red) in response to voltage commands stepping from −170 mV to 100 mV in 4 mV step. Superimposed on the ramp were two sinusoids (10 mV in amplitude) with frequencies of 390 and 781 Hz. The cell was held at −70 mV. The responses in A were the result of average of 3 trials. B. The voltage dependence of motility and NLC. Motility response (thin red line) was fit with a two-state Boltzmann function (heavy red line). NLC (dotted blue lines) was fit by a two state Boltzmann function (heavy blue line). C. Motility sensitivity and NLC. Note that the slopes of motility and NLC were essentially identical. D. Normalized charge movement and length change as a function of voltage.

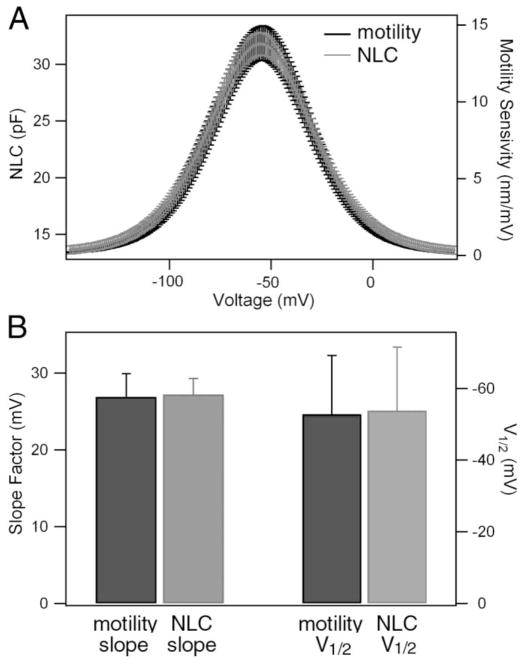

Fig. 3A exhibits the means and SDs of the NLC and motility sensitivity as a function of voltage from 14 gerbil OHCs. The two curves overlapped, suggesting that their voltage dependency was essentially identical. We computed the slope factor (α) and V1/2 from these cells. The two parameters are presented in Fig. 3B. The mean values of the slope factor for electromotility and NLC were 26.9 ± 3.0 mV and 27.2 ± 2.1 mV, respectively, whereas the mean V1/2 values were −53.8 ± 17.7 mV and −55.8 ± 16.4 mV, respectively. No statistical difference was found between them in either groups (Student’s t test: P > 0.05 for both groups).

Figure 3.

A. The means ± SD of the slope functions of NLC and motility (n=14). B. Slope factor and V1/2 obtained from these cells. The slope factor of NLC is defined as α, where α = ze/kT (see the methods section).

DISCUSSION

One of the distinctive morphological features of OHCs is the possession of high density IMP particles (Gulley and Reese, 1977) with packing density estimated to be from 2,500 to 3,000 μm−2 (Saito, 1983; Kalinec et al., 1992) to as much as 6,000 μm−2 (Forge, 1991) in the lateral plasma membrane. The diameter of the particles is between 10 and 15 nm, with the highest population at 12 nm. This is also supported by AFM observation of similar sized particles on the surface of prestin-transfected human embryonic kidney cells (Murakoshi et al. 2006). Based on the packing density of IMPs and the density of charge transferred with a two-state model, we conclude that each IMP contains four prestin molecules in gerbil OHCs. In mouse OHCs where both IMP density and charge density were measured and compared in a previous study (He et al., 2010), it was also concluded each IMP contained four prestin molecules. The conclusion is consistent with two recent studies which suggest that prestin exists as a higher order oligomer, most likely as a tetramer (Zheng et al., 2006; Mio et al., 2008).

Our conclusion that prestin forms tetramers relies on two conclusions from previous studies: 1) The 12-nm IMPs densely packed in the basolateral membrane of OHCs are indeed prestin; 2) The average density of IMPs is about 5,500 particles μm−2 for adult gerbil (Köpple et al., 2004). Several studies have provided strong evidence that the IMPs with diameter of 10 to 15 nm are prestin. The first piece of evidence comes from developmental studies in which the onset of OHC motility and appearance of IMPs were compared in the same species. Souter et al. (1995) examined the maturation of the membrane specializations of the neonatal gerbil OHCs. They showed that IMP density increased significantly from 2,200 μm−2 to 4,131 μm−2 between 2 and 8 days after birth. OHCs develop electromotility and NLC from 4 to 7 days after birth (He et al., 1994), concomitant with increase in the density of IMPs. Another piece of evidence comes from studies using prestin knockout mice. When prestin no longer exists in the membrane, the density of IMPs is significantly reduced from an average density of ~5,500 μm−2 in the wild-type to ~2,000 μm−2 in the prestin knockout OHCs (He et al., 2010). The average size of the remaining particles is significantly reduced (to ~8 nm). These small size proteins are apparently not prestin and are repopulating the lateral plasma membrane in place of the missing prestin (He et al., 2010). The density and size of the IMPs of prestin-null OHCs resemble those of cochlear Deiters’ cells. Collectively, these studies suggest that the large-size IMPs densely packed in the basolateral membrane of OHCs are prestin.

Our conclusion is also based on the IMP density count obtained by freeze-fracture techniques and electron microscopy. The IMP density shows a large variation among different studies and species. In gerbils where data from newborn and adult animals are available for comparison, the density varies from 4,160 to 7,150 particles μm−2 (Köppl et al., 2004). Using the median density of 5686 μm−2 (Köppl et al. 2004), we estimated that the number of prestin molecules in each IMP was 4. However, if we used the high- or low-end value (4,160 or 7,150 μm−2), each IMP would then contain 3 or 5 prestin molecules. Since the median value used represents the majority of the population, it is likely that most prestin molecules exist as tetramers in the membrane. Nevertheless, we can not rule out the possibility that prestin molecules may form other higher-order oligomers. Dimer, trimer, and tetramer are among those seen in the prestin-expressing cell lines and in OHCs using biochemical methods (Zheng et al., 2006; Detro-Dassen et al., 2007). We should point out that the total motility-related charge density per square micron reported in our study is significantly higher than that reported by Santos-Sacchi et al. (1998). This may reflect the fact that in a typical measurement, the charge density can be underestimated due to the detrimental effect of enzymatic digestion and damage during isolation. Therefore, we only selected OHCs that had the higher charge density for our calculation. We noted that our measurements were obtained from apical turn OHCs. It is not clear whether the charge density and the IMP density would be different in the basal turn OHCs.

One more issue that can affect our conclusion and requires further discussion is z, valence of charge movement according to the two-state Boltzmann function (Eq. 1, 2). The valence is ~0.8 for both OHCs (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991) and prestin-transfected heterologous cells (Zheng et al., 2000; Oliver et al., 2001), implying that a fraction of ~0.8 of an elementary charge is moved across the cell membrane. Equivalently, this value represents a single elementary charge moved across the 80% of the membrane electric field. The valences calculated from motility function and NLC measurements in our study are both ~0.8. The general assumption is that the similarity of the valences of OHC motility and charge movement indicates the existence of a single voltage-sensing particle with an absolute charge magnitude close to 1e− (Santos-Sacchi, 1991). Our conclusion that each IMP contains 4 prestin monomers is based on the assumption that each prestin molecule contains one single voltage sensing particle. We should point out that the valence of 0.8 could also be interpreted as two elementary charges transferring across 40% of the membrane electrical field (Dallos and Fakler, 2002). Each IMP would contain two prestin molecules in that case.

Prestin is a highly hydrophobic protein (Zheng et al., 2000; Deak et al., 2005). Proteins with hydrophobic natures have a propensity to aggregate. Several studies using coimmuno-precipitation and colocalization, and fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy have showed that prestin indeed interacts with itself and possibly other proteins (Deak et al., 2005; Navaratnam et al., 2005; Zheng et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2007). It is well known that ion channels and transporters in the membrane form oligomers and that the nature of oligomerization influences the properties of gating and selectivity. For example, the voltage-gated K+ channel, KcsA, is a tetramer (Sansom et al., 2002; Swartz, 2008). The sodium (Na+)-coupled aspartate (GltPh) transporter is a trimer and contains a dual intramembrane gating system that prevents formation of a channel (Boudker et al., 2007; Yernool et al., 2004). In both cases, the subunits form one functional unit that determines the ion selectivity and pore size. Since prestin molecules can interact and form tetramers or other higher-order oligomers, it is important to determine whether the monomers in the oligomer form one single motor unit or whether each monomer in the oligomer is mechanically independent from each other with each interacting with cytoplasmic or other partners to facilitate the mechanical response. We addressed this issue by measuring NLC and motility simultaneously from the same cells. If the mechanical responses of the 4 elements of the tetramer are independent and in parallel, then the slope of the motility function should be the same as that of the NLC function. If, however, the 4 units constitute a single mechanical unit (in series), one would expect that the motility function is 4-times steeper than the NLC function. We showed that the slope factors of motility and NLC were the same. This suggests that each prestin subunit is mechanically independent in the tetramer. Therefore, while prestin is structurally a tetramer, it is functionally four parallel monomers (Zheng et al., 2006) with each monomer interacting independently with cytoplasmic or downstream partners to facilitate the mechanical response.

Ashmore (1990) showed that motility and NLC have the same activation kinetics. Santos-Sacchi (1991) further demonstrated that the two measures can reversibly be blocked by external application of gadolinium ions. Two recent studies using prestin knock-in models have shown that prestin mutations causing shift and reduction in the voltage dependence and magnitude of NLC also produce the comparable shift and reduction in the voltage dependence and magnitude of motility (Gao et al., 2007; Dallos et al., 2008). These observations have led to the notion that motility and NLC are essentially exchangeable measures (Dallos and Fakler, 2002; Ashmore, 2008) and thus, the NLC can serve as an electrical ‘signature’ of motility. Although previous studies have measured and compared NLC and motility (Santos-Sacchi, 1991; Tunstall et al., 1995), the measurements were not entirely consistent and the results were inconclusive. We took the advantage of measuring motility and NLC simultaneously from the same OHCs to minimize the influence of the changes of mechanical (e.g., turgor pressure) and metabolic conditions of the cells during recordings. This would allow us to determine whether the voltage sensor and the actuator were fully coupled. We showed that the values of α and V1/2 between motility and NLC were not statistically different (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3), supporting the general notion that the NLC and motility are fully coupled. Thus, we conclude that the charge movement is directly converted into conformational change of the prestin molecule.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

1. Whole-Cell Voltage-Clamp and Nonlinear Capacitance Measurements

Adult gerbils (aged between 28 and 35 days after birth) were decapitated following a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital injection (200 mg/kg, IP). Care and use of the animals in this study were approved by grants from the NIDCD/NIH, and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Creighton University. The cochleae were dissected and kept in cold tissue culture medium (Leibovitz’s L-15). The organ of Corti was isolated, and after brief enzymatic digestion (1 mg/mL type IV Collagenase, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), the tissues were transferred to small plastic chambers filled with enzyme-free culture medium. Solitary cells were obtained after gentle trituration. The bath solution contained (mM): 120 NaCl, 20 TEA-Cl, 2 CoCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose. Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were performed on an Olympus inverted microscope (IX71) with differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. The patch pipette with the headstage of an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments) was held by a Narishige 3D micromanipulator (MHW-3). Whole cell voltage-clamp tight-seal recordings were established. The patch electrodes were pulled from 1.5 mm glass capillaries (WPI) using a Flaming/Brown Micropipette Puller (Sutter Instrument Company, Model P-97). Recording pipettes had open tip resistances of 2–3 MΩ and were filled with an internal solution that consisted of (mM): 140 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES. The osmolarity and pH for both intracellular and extracellular solutions were adjusted to 300 mOsm/l and 7.3. The access resistance typically ranges from 6 to 12 MΩ after the whole-cell recording configuration was established. Voltage error due to the uncompensated series resistance was compensated off-line. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22±2°C).

The AC technique was used to obtain motility-related gating charge movement and the corresponding nonlinear membrane capacitance. This technique has been described in details elsewhere (Santos-Sacchi et al. 1998). In brief, it utilized a continuous high-resolution two-sine voltage stimulus protocol (10 mV for both 390.6 and 781.2 Hz), with subsequent fast Fourier transform-based admittance analysis. In some cases, 20 mV were used for both 390.6 and 781.2 Hz to evoke large motility. These high frequency sinusoids were superimposed on staircase voltage (in 4 mV steps) stimuli. The evoked capacitive currents were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 100 kHz using jClamp software (SciSoft Company), running on an IBM-compatible computer and a 16-bit A/D converter (Digidata 1322, Molecular Devices).

The prestin-related charge movement (Q) derived from gating current data can be described by the two-state Boltzmann function as:

| (1) |

where Qmax is the maximum charge transfer, V1/2 is the voltage at which Q = 0.5 Qmax, α is the slope of the voltage dependence of charge transfer based on the statistical mechanics of a charge distributed across the electric field of the plasma membrane and is given by α = ze/kT, where e is the elementary charge on electron (1.64 × 10−19 Coulombs), z is the valence of the charge movement, kB = 1.35 × 10−16 J/0K, is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

The nonlinear capacitance can be described as the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function relating nonlinear charge movement to voltage (Ashmore, 1989; Santos-Sacchi, 1991). The capacitance function is described as:

| (2) |

2. Motility Measurements

Motility and NLC evoked by the voltage protocol described above were acquired simultaneously using the two input channels. Motility was measured and calibrated by a photodiode-based measurement system (Jia and He 2005) mounted on the Olympus microscope. The magnified image of the edge of the cell was projected onto a photodiode through a rectangular slit. Somatic length changes, evoked by voltage stimuli, modulated the light influx to the photodiode. The photocurrent response was calibrated to displacement units by moving the slit a fixed distance (0.5 μm) with the image of the cell in front of the photodiode. After amplification, the photocurrent signal was low-pass filtered by an anti-aliasing filter before being digitized by a 16-bit A/D board (Digidata 1322, Molecular Devices). The photodiode system had a cutoff (3 dB) frequency of 1100 Hz. The motile responses were filtered at 1100 Hz and digitized at 100 kHz. The voltage dependence of the cell length change also fits with the two-state Boltzmann function and can be described as:

where Lmax is the maximal length change, V1/2 is the voltage at which L = 0.5Lmax, α is the slope factor indicating the voltage sensitivity of the length change. Slope function was obtained as the derivative of the Boltzmann function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant R01 DC004696 from the NIDCD to DH, and by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 30628030 to SY and DH. We thank Drs. Peter Dallos, Stephen Neely, Yi-Wen Liu, and Ben Currall for many helpful discussions. The project described was, in part, supported by grant number G20RR024001 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashmore JF. Motor coupling in mammalian outer hair cells. In: Wilson JP, Kemp DT, editors. Cochlear Mechanisms. Plenum; New York: 1989. pp. 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore JF. Forward and reverse transduction in the mammalian cochlea. Neurosci Res Suppl. 1990;12:S39–S50. doi: 10.1016/0921-8696(90)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore JF. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudker O, Ryan RM, Yernool D, Shimamoto K, Gouaux E. Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature. 2007;445:387–393. doi: 10.1038/nature05455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, De RY. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Evans B, Hallworth R. Nature of the motor element in electrokinetic shape changes of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 1991;350:155–157. doi: 10.1038/350155a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Fakler B. Prestin, a new type of motor protein. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:104–111. doi: 10.1038/nrm730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallos P, Wu X, Cheatham MA, Gao J, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Jia S, Wang X, Cheng WH, Sengupta S, He DZ, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deák L, Zheng J, Orem A, Du GG, Aguiñaga S, Matsuda K, Dallos P. Effects of cyclic nucleotides on the function of prestin. J Physiol. 2005;563:483–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detro-Dassen S, Schanzler M, Lauks H, Martin I, zu Berstenhorst SM, Nothmann D, Torres-Salazar D, Hidalgo P, Schmalzing G, Fahlke C. Conserved dimeric subunit stoichiometry of SLC26 multifunctional anion exchangers. J Biol Chem. 2007;283:4177–4188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A. Structural features of the lateral walls in mammalian cochlear outer hair cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;265:473–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00340870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Wang X, Wu X, Aguinaga S, Huynh K, Jia S, Matsuda K, Patel M, Zheng J, Cheatham M, He DZ, Dallos P, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell electromotility in knockin mice does not appear to adjust the operating point of a cilia-based amplifier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12542–12547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700356104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulley RL, Reese TS. Regional specialization of the hair cell plasmalemma in the organ of Corti. Anat Rec. 1977;189:109–123. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091890108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZ, Evans BN, Dallos P. First appearance and development of electromotility in neonatal gerbil outer hair cells. Hear Res. 1994;78:77–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZ, Dallos P. Somatic stiffness of cochlear outer hair cells is voltage-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8223–8228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He DZ, Jia SP, Sato T, Zuo J, Andrade LR, Riordan GP, Kachar B. Changes in plasma membrane structure and electromotile properties in prestin deficient outer hair cells. Cytoskeleton. 2010;67:43–55. doi: 10.1002/cm.20423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates Inc; Sunderland: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Santos-Sacchi J. Mapping the distribution of the outer hair cell motility voltage sensor by electrical amputation. Biophys J. 1993;65:2228–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia S, He DZ. Motility-associated hair-bundle motion in mammalian outer hair cells. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1028–1034. doi: 10.1038/nn1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachar B, Brownell WE, Altschuler R, Fex J. Electrokinetic shape changes of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 1986;322:365–368. doi: 10.1038/322365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec F, Holley MC, Iwasa KH, Lim DJ, Kachar B. A membrane-based force generation mechanism in auditory sensory cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8671–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köpple C, Forge A, Manley GA. Low density of membrane particles in auditory hair cells of lizards and birds suggests an absence of somatic motility. J Comp Neurol. 2004;479:149–155. doi: 10.1002/cne.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio K, Kubo Y, Ogura T, Yamamoto T, Arisaka F, Sato C. The motor protein prestin is a bullet-shaped molecule with inner cavities. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1137–1145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakoshi M, Gomi T, Iida K, Kumano S, Tsumoto K, Kumagai I, Ikeda K, Kobayashi T, Wada H. Imaging by atomic force microscopy of the plasma membrane of prestin-transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2006;7:267–278. doi: 10.1007/s10162-006-0041-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaratnam D, Bai JP, Samaranayake H, Santos-Sacchi J. N-terminal-mediated homomultimerization of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Biophys J. 2005;89:3345–3352. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes FD, Lopez LN, Lin HW, Davies C, Azevedo RB, Gow A, Kachar B. Distinct subdomain organization and molecular composition of a tight junction with adherens junction features. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4819–4827. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K. Fine structure of the sensory epithelium of guinea-pig organ of Corti: subsurface cisternae and lamellar bodies in the outer hair cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;229:467–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00207692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom MS, Shrivastava IH, Bright JN, Tate J, Capener CE, Biggin PC. Potassium channels: structures, models, simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1565:294–307. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3096–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacchi J, Kakehata S, Kikuchi T, Katori Y, Takasaka T. Density of motility-related charge in the outer hair cell of the guinea pig is inversely related to best frequency. Neurosci Lett. 1998;256:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00788-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souter M, Nevill G, Forge A. Postnatal development of membrane specializations of gerbil outer hair cells. Hear Res. 1995;91:43–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz KJ. Sensing voltage across lipid membranes. Nature. 2008;456:891–897. doi: 10.1038/nature07620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall MJ, Gale JE, Ashmore JF. Action of salicylate on membrane capacitance of outer hair cells from the guinea-pig cochlea. J Physiol. 1995;485:739–752. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Currall B, Yamashita T, Parker LL, Hallworth R, Zuo J. Prestin-prestin and prestin-GLUT5 interactions in HEK293T cells. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67:483–497. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yernool D, Boudker O, Jin Y, Gouaux E. Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature. 2004;431:811–888. doi: 10.1038/nature03018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Shen W, He DZ, Long KB, Madison LD, Dallos P. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–155. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Du GG, Anderson CT, Keller JP, Orem A, Dallos P, Cheatham M. Analysis of the oligomeric structure of the motor protein prestin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19916–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]