Abstract

A widely used technique for coordinate‐based meta‐analyses of neuroimaging data is activation likelihood estimation (ALE). ALE assesses the overlap between foci based on modeling them as probability distributions centered at the respective coordinates. In this Human Brain Project/Neuroinformatics research, the authors present a revised ALE algorithm addressing drawbacks associated with former implementations. The first change pertains to the size of the probability distributions, which had to be specified by the used. To provide a more principled solution, the authors analyzed fMRI data of 21 subjects, each normalized into MNI space using nine different approaches. This analysis provided quantitative estimates of between‐subject and between‐template variability for 16 functionally defined regions, which were then used to explicitly model the spatial uncertainty associated with each reported coordinate. Secondly, instead of testing for an above‐chance clustering between foci, the revised algorithm assesses above‐chance clustering between experiments. The spatial relationship between foci in a given experiment is now assumed to be fixed and ALE results are assessed against a null‐distribution of random spatial association between experiments. Critically, this modification entails a change from fixed‐ to random‐effects inference in ALE analysis allowing generalization of the results to the entire population of studies analyzed. By comparative analysis of real and simulated data, the authors showed that the revised ALE‐algorithm overcomes conceptual problems of former meta‐analyses and increases the specificity of the ensuing results without loosing the sensitivity of the original approach. It may thus provide a methodologically improved tool for coordinate‐based meta‐analyses on functional imaging data. Hum Brain Mapp 2009. © 2009 Wiley‐Liss, Inc.

Keywords: fMRI, PET, permutation, between‐subject variability, variance, random‐effects

INTRODUCTION

Functional neuroimaging has provided ample information about the location of cognitive and sensory processes in the human brain. Nevertheless, it carries several limitations, including rather small sample sizes, low reliability [Feredoes and Postle,2007; Raemaekers et al.,2007], and its inherent subtraction logic, which is only sensitive to differences between conditions [Price et al.,2005; Stark and Squire,2001]. Consequently, integration of data from several studies in order to identify locations, which show a consistent response across experiments (collectively involving hundreds of subjects and numerous variations in experimental design), has become an important task. Such meta‐analyses started by textual and graphical summaries [Joseph,2001; Peyron et al.,2000] and have progressed to quantitative approaches for detecting significant convergence among reported coordinates [Eickhoff et al.,2006a; Farrell et al.,2005; Price et al.,2005; Wager et al.,2004; Wager and Smith,2003].

One of the most common algorithms for coordinate‐based meta‐analyses is activation likelihood estimation [ALE; Turkeltaub et al.2002, Laird et al.2005], which treats reported foci not as points but as spatial probability distributions centered at the given coordinates. ALE maps are then obtained by computing the union of activation probabilities for each voxel. To differentiate true convergence of foci from random clustering (i.e., noise), a permutation test is applied: to obtain an ALE null‐distribution the same number of foci as in the real analysis are randomly redistributed throughout the brain and ALE maps are computed as described above. The histogram of the ALE scores obtained from several thousands of random iterations is then used to assign P values to the observed (experimental) values.

In spite of its success, ALE still has some conceptual drawbacks: First, the size of the modeled Gaussians is manually set to match the “average” smoothing kernel of the original experiments, and hence largely subjective. Moreover, the uncertainty in spatial location should not depend on the applied smoothing [Fox et al.,2001]. Rather, its main constituents are (i) the “between‐subject variance” (due to the small sample sizes) and (ii) the “between‐template variance” introduced by different normalization strategies (a main determinant of between‐laboratory variance).

Secondly, the permutation analysis is anatomically unconstrained and hence includes deep white matter in spite of the predominant location of “true” activations within the cerebral cortex, inducing a potential bias in the permutation statistics.

Finally, the current statistical approach is designed to test for above‐chance clustering of individual foci (fixed‐effects analysis) not of results from different experiments (random‐effects analysis). Only random‐effects studies, however, allows generalization of the results beyond the analyzed studies [Penny and Holmes,2003; Wager et al.,2007].

To overcome these limitations and to provide a more valid framework for ALE meta‐analyses, we here present an empirical estimation of both between‐subject and between‐template variances in fMRI studies, and propose a revised algorithm for ALE analyses, which includes an explicit modeling of the uncertainty associated with a given focus, an anatomically constrained analysis space and a random‐effects inference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Quantification of Between‐Subject and Between‐Template Variance

Experimental design and setup

In order to provide empirical estimates for the between‐subject and between‐template variance we used data from a previous fMRI study [Grefkes et al.,2008b] supplemented by additional volunteers. In total 21 subjects (13 males, age 39.6 ± 14.9 years) with no history of neurological or psychiatric diseases participated after informed consent and approval by the local ethics committee. In the experiment, subjects were asked to perform whole hand fist opening and closing movements with either the left (LH) or right (RH) hand (a third condition in the original experiment was not considered here) in a block‐design. The instruction for the upcoming block was first presented from video screen. After a jittered delay the circle started blinking at a frequency of 1.5 Hz, requiring the subjects to perform the fist closing movements synchronously to these blinks. After 15 s, the blinking circle was replaced by a white screen indicating the subjects to rest for 15 s until the next block started. The experiment consisted of 24 pseudo‐randomized activation blocks (counterbalanced across subjects) and 26 resting baselines between, before and after the activation blocks.

Image acquisition and processing

Functional MR images were acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) whole‐body scanner using a gradient echo EPI sequence sensitive to the blood oxygenation level‐dependent (BOLD) effect using the following imaging parameters: TR = 1600 ms, TE = 30 ms, FoV = 200 mm, 26 axial slices, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, in‐plane resolution = 3.1 × 3.1 mm, flip angle = 90°, and distance factor = 10%. Additional high‐resolution anatomical images were acquired for all subjects using a 3D MPRAGE (magnetization‐prepared, rapid acquisition gradient echo) sequence with the following parameters: TR = 2250 ms, TE = 3.93 ms, FoV = 256 mm, 176 sagittal slices, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, in‐plane resolution = 1.0 × 1.0 mm, flip angle = 9°, and distance factor = 50%. Each fMRI time series consisted of 457 images and was preceded by 4 dummy images allowing the MR scanner to reach a steady state in T2* contrast. After the acquisition of the dummy images, the experiment started with a baseline condition. For image preprocessing and analysis we used the SPM 5 software package (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk). The EPI volumes were first corrected for between scan movement [Ashburner and Friston,2003]. Each subject's data was then transformed into standard stereotaxic space using nine different normalization approaches (Table I). Importantly, all of these approaches spatially normalized the data into the standard space of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI).

Table I.

Normalization procedures applied to the data acquired for each of the 21 single subjects for spatial normalization into the MNI reference space

| Normalization | Source | Target | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lin2MNI152 | T1 | MNI‐152 template | 12 dof affine transformation |

| Norm2MNI152 | T1 | MNI‐152 template | Nonlinear discrete cosine transform |

| Lin2Colin27 | T1 | MNI single subject template | 12 dof affine transformation |

| Norm2Colin27 | T1 | MNI single subject template | Nonlinear discrete cosine transform |

| Lin2EPI | EPI | FIL EPI template (MNI space) | 12 dof affine transformation |

| Norm2EPI | EPI | FIL EPI template (MNI space) | Nonlinear discrete cosine transform |

| Seg2TPM | EPI | MNI tissue probability maps | Unified segmentation |

| Seg2Colin | EPI | MNI single subject template | Unified segmentation |

| Seg2TPM2Colin | EPI | MNI single subject template (via MNI tissue probability maps) | Unified segmentation |

For those normalization approaches, where the source image is designated as “EPI”, the mean of the subjects EPI images following movement correction was directly used for normalization. Those approaches, where the source image is designated as “T1”, the high‐resolution anatomical scan of each subject was first linearly coregistered to the corresponding mean EPI image before the transformation parameters (moving the individual subject's data into standard space) was computed from this T1 weighted image. Also note that while all computations were carried out using SPM5, the first approach (Lin2MNI152) is equivalent to the FLIRT procedure used for spatial normalization within FSL (www.fsl.fmrib.ox.ax.uk).

The images of all nine time‐series for each subject were spatially smoothed using an isotropic 6 mm Gaussian kernel. Identical single‐subject analyses were performed for each time‐series, using a general linear model consisting of box‐car reference functions for each condition convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response [Kiebel and Holmes,2003]. Movement parameters (estimated before normalization and hence identical across datasets) were added as covariates to control for movement related variance. Simple main effects for each experimental condition were calculated for each subject by applying appropriate baseline contrasts.

Random‐effects group analyses were computed separately for each normalization approach by feeding the respective first‐level (individual) contrasts into a second‐level ANOVA (factor: condition, blocking factor: subject). In the modeling of variance components, we allowed for violations of sphericity by modeling nonindependence across parameter estimates from the same subject, and allowing unequal variances both between conditions and subjects.

Quantification of variances

The goal of this study was to provide empirical estimates for the between‐subject and between‐template variance of the stereotaxic locations of local maxima. The reason behind this approach is that local maxima coordinates are usually reported in fMRI studies and represent the data for ALE meta‐analyses. We hence identified the local maxima for 16 different brain regions (summarized in Table II) in each of the nine random‐effects analyses (analyzing the same subjects but differing in the applied spatial normalization). Moreover, all coordinates for the local maxima of these16 regions were also identified in the 189 (21 subjects × 9 normalizations) individual single subject analyses. The stereotaxic coordinates for the local maxima in the single‐subject analyses were determined based on assessing the individual SPM[t] maps for the contrasts listed in Table II. In these maps the local maximum (at P < 0.05 uncorrected) closest to the corresponding group maximum was then located. This approach has emerged as the standard for identifying the location of corresponding activations in individual subjects as needed for example to extract time courses for effective connectivity analyses [Booth et al.,2007; Heim et al., in press; Mechelli et al.,2005] and represents the robust approach for localizing functionally equivalent regions in single‐subject neuroimaging datasets. All local maxima were recorded in terms of their stereotaxic coordinates in millimetres, i.e., “world‐space.”

Table II.

Overview of the regions whose variance with respect to stereotaxic location between subjects and normalization procedures analyzed in the present study

| Region | Abbreviation | Contrast |

|---|---|---|

| M1 left | M1 L | R > 0 ∩ R > L |

| SMA left | SMA L | R > 0 ∩ R > L |

| SII left | SII L | R > 0 ∩ R > L |

| M1 right | M1 R | L > 0 ∩ L > R |

| SMA right | SMA R | L > 0 ∩ L > R |

| SII right | SII R | L > 0 ∩ L > R |

| PMC left | PMC L | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| PMC right | PMC R | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| Caudate nucleus left | CN L | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| Caudate nucleus right | CN R | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| V5 left | V5 L | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| V5 right | V5 R | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| Dorsal PFC left | PFC | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| Ventral PMC left | vPMC | L > 0 ∩ R > 0 |

| V1 | V1 | 0 > (L + R) |

| Medial posterior parietal cortex | PPC | 0 > (L + R) |

The contrasts refer to the following experimental conditions: L, paced left hand movements; R, paced right hand movements; 0, resting baseline.

To obtain an estimate for the between‐subject variance of the spatial localization of the local maxima, we computed (separately for each normalization procedure) the average Euclidean distance between the corresponding maxima of different subjects. That is, for each region, we computed the mean of the distances between the individual local maxima for that region obtained for each possible pair of subjects. Likewise, the between‐template variance in spatial localization of local maxima was estimated by the average Euclidean distance between the corresponding maxima of the different group analyses obtained from the same set of subjects.

The Modified ALE Algorithm

Uncertainty modeling

The width of the modeled probability distribution should reflect the uncertainty of the reported spatial location due to between‐template and between‐subject variance. In the subsequent paragraphs, the mean Euclidean Distance between corresponding foci of different subjects will be referred to as EDsub, the mean Euclidean Distance between corresponding maxima as observed in the different group‐analyses (differing only in spatial normalization) as EDtemp. These values (EDsub/EDtemp) will henceforth be used as empirical estimates of the between‐subject and between‐template variability in the stereotaxic coordinates of functional neuroimaging results. In order to model the spatial uncertainty associated with a reported focus, these EDs first have to be transformed into the equivalent kernel sizes of Gaussian distributions used in ALE analysis. Note, that this procedure requires the assumption of an isotropic normal distribution of all displacements relative to the “true” locations. That is, we have to assume that EDsub and EDtemp reflect the mean distance between locations that are independent realizations of an isotropic and stationary (across voxels) Gaussian displacement. This is a strong assumption but necessary in the absence of voxel‐wise empirical data on spatial uncertainty. If these assumptions are made, however, the displacement can readily be described using a Maxwell‐Boltzmann distribution. This distribution stems from the kinetic theory of gases and describes the distribution of distances (vector magnitudes) between particles that result from their random motion in three dimensions. In this theory, the motion components along each dimension are assumed to be independently and normally distributed, i.e., following the same assumptions we made for the misplacement of the activation foci. In the basic form of the Maxwell‐Boltzmann distribution, each of the three underlying normal distributions (X, Y, Z displacement) has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of α. The Euclidean distances computed from our empirical data should hence be distributed according to a Maxwell‐Boltzmann distribution whose α‐parameter corresponds to the desired σ (standard deviation) of the underlying Gaussians displacement. Importantly, the point‐estimator μ of a Maxwell‐Boltzmann distribution (corresponding the mean of our empirical data) can easily be derived if its α‐parameter is known [μ = 2α√(2/π)]. In order to derive this α‐parameter and hence the σ of the Gaussian displacement, the mean Euclidean Distances calculated from our data were thus substituted the empirical estimate of μ. Solving the equation for α then yields the σ of the underlying Gaussian distribution of the displacements.

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

Given the σ of a Gaussian distribution, the corresponding FWHM parameters can readily be computed as follows:

| (2a) |

| (2b) |

Since the measuring error in Gaussian systems scales inversely to the square root of the number of observations (reduction of sampling error), an approximation of the spatial uncertainty due to inter‐subject variability in a group of N (appropriately sampled) subjects can be estimated as

| (3) |

In order to obtain the spatial uncertainty of a given coordinate the two components outlined above have to be combined into one Gaussian distribution. As Gaussian kernels combine by Pythagoras' rule, the final FWHM used to model the uncertainty in spatial location of the activations reported by a particular study is hence given by

|

(4) |

Spatial inference

The focus of spatial inference in meta‐analysis should lie on answering the question: “Where is the convergence across experiments higher as it would be expected if their results were independently distributed?” Importantly, however, this independence under the null‐distribution should only pertain to the relationship between different studies. In contrast, the spatial relationship between the individual foci reported for any given study (i.e., their codistribution structure) must be considered a given property of this study and hence unchangeable. This distinction represents a key modification of previous ALE implementations and entails the change from fixed‐effects (convergence between foci) to random‐effects (convergence between studies but not individual foci reported for the same study) inference. In other words, to allow random‐effects inference the distribution of foci within each study must be conserved as a fixed property, focusing the analysis on convergence across different experiments. In order to accommodate these requirements we applied the following procedure. First, all foci reported for a given study are modeled as Gaussian probability distributions as described above. The information provided by the foci of a given study is then merged into a single 3D‐volume. To this end, the modeled probabilities are combined over all foci reported in that experiment by taking the voxel‐wise union of their probability values (i.e.,

, where p(i) is the probability associated with the ith focus at this particular voxel). Hereby a “modeled activation” (MA) map is computed. This map contains for each voxel the probability of an activation being located at exactly that position based on the reported coordinates and the employed model of spatial uncertainty (cf. Fig. 6, panel B1). The MA map can hence be conceptualized as a summary of the results reported in that specific study taking into account the spatial uncertainty associated with the reported coordinates.

, where p(i) is the probability associated with the ith focus at this particular voxel). Hereby a “modeled activation” (MA) map is computed. This map contains for each voxel the probability of an activation being located at exactly that position based on the reported coordinates and the employed model of spatial uncertainty (cf. Fig. 6, panel B1). The MA map can hence be conceptualized as a summary of the results reported in that specific study taking into account the spatial uncertainty associated with the reported coordinates.

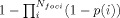

Figure 6.

A1: Location of the 24 individual activation foci as reported in an exemplary finger tapping experiment (Gerardin et al.,2000). A2: Summary of the 883 individual activation foci reported in all 73 experiments included in the meta‐analysis (cf. Table III). B1: modeled activation (MA) map resulting from centring Gaussian distributions of 7.02 mm FWHM (based on 8 subjects and estimates of 11.6 mm for EDsub and 5.7 mm for EDtemp) at the location of the foci displayed in A1. B2: Activation likelihood estimates (ALE), reflecting, for each voxel, the union of the MA maps (exemplified in B1) across all experiments. C1: Histogram of the ALE scores obtained in the permutation analysis, i.e., under the assumption of a random spatial association between studies. The values summarized in this histogram hence reflect the null‐distribution against which the experimental ALE scores are compared in order to compute their respective P values. Note, that the empirical null‐distribution is sufficiently smooth even in regions of higher ALE scores to allow a reliable attribution of significance levels to the obtained experimental ALE scores, underlining the benefit of the large numbers of permutations used in their construction. C2: The clusters of significant (P < 0.05, corrected) convergence across studies, i.e., significant voxels from B2 and hence results of the performed meta‐analysis, as assessed by comparison with an empirical null distribution by permutation testing (cf. C1). All data is displayed on a surface view of the MNI single subject template.

Following the original definition of ALE scores are then calculated on a voxel‐by‐voxel basis by taking the union of these individual MA maps. Given that functional activations are predominantly located in the grey matter, this computation was confined to a broadly defined grey matter shell (>10% probability for grey matter, based on the ICBM tissue probability maps [Evans et al.,1994]). The resulting images then contain for each voxel of this anatomically constrained analysis space an ALE score representing the convergence of reported foci at that position.

To enable spatial inference on these ALE scores, an empirical null‐distribution has to be established which allows distinguishing random convergence (noise) from locations of true convergence in the reported coordinates. Importantly, this distribution should reflect the null‐hypothesis of a random spatial association between experiments. That is, the null‐distribution against which the experimental ALE scores are compared should represent the distribution of ALE scores that would be obtained if no true (neurobiological) convergence would be present. In such a case, any overlap between the MA maps of different studies would only happen by chance. In line with previous approaches [Laird et al.,2005; Turkeltaub et al.,2002; Wager et al.,2007], the null‐distribution for inference on the ALE scores is computed nonparametrically by a permutation procedure. In this procedure, a random association between the MA maps obtained from each study was established by sampling each map at an independently chosen random location. In order to constrain the sampling of the individual MA maps to the same locations as considered in the actual analysis, however, the voxels from which the random locations were drawn were restricted to the same grey matter mask as described above. In practice, this approach consists of picking a random grey matter voxel from the MA map of study 1, then picking a (independently sampled) random grey matter voxel from the MA map of study 2, study 3, etc. until one voxel was selected from each MA map. The respective activation probabilities (i.e., the values of the MA maps at the selected voxels) were then recorded, yielding as many values as there had been studies included in the meta‐analysis. Importantly, however, these values correspond to MA values, i.e., activation probabilities, that were sampled from random, spatially independent locations. The union of these activation probabilities is then computed in the same manner as done for the meta‐analysis itself in order to yield an ALE score under the null‐hypothesis of spatial independence. This ALE score is recorded and the procedure iterated by selecting a new set of random locations and computing another ALE score under the null‐distribution.

It is important to note that in this permutation approach each of the individual iterations only yields a single ALE value under the null‐distribution. This is an important distinction to the conventional approach to ALE analyses, where a complete volume of ALE scores (consisting of ∼400,000 voxels, i.e., individual values) under the null‐hypothesis is obtained in a single iteration. Consequently, the number of iterations has to be increased accordingly to compensate for this imbalance. In the present analysis, we used 1011 iterations of the permutation in order to construct a sufficient sample of the ALE null‐distribution against which the experimental data may be assessed, as opposed to 10,000 or more full volumes as in the conventional analysis. This number could easily be lowered to speed up the computation, e.g., for obtaining preliminary results. It should, however, be considered, that even this amount of iterations (which can usually be computed in about a day) is rather small in relation to the number of theoretically possible permutations and that reliability and efficiency of nonparametric statistics depend on the number of samplings relative to the possible permutations [Nichols and Holmes,2002].

Example Data

Real data

The modified ALE approach is illustrated by a meta‐analysis on the brain activity evoked by finger tapping experiments [Laird et al.,2008]. Using the BrainMap database (http://www.brainmap.org), 38 papers reporting 73 individual experiments (347 subjects) with a total of 883 activation foci were obtained (Table III, cf. Fig. 6). For comparison, meta‐analysis on these reported activations was also carried out using the original ALE algorithm [Turkeltaub et al.,2002] as implemented in the UTHSC GingerALE software (http://www.brainmap.org/ale) using 10,000 permutation to establish the null‐distribution. Both analyses were thresholded at a false discovery rate (FDR) corrected threshold of P < 0.05 [Genovese et al.,2002; Laird et al.,2005] and an additional cluster extend threshold of k = 10 voxels.

Table III.

Overview of the individual experiments included in the meta‐analysis used to exemplify the new approach for activation likelihood estimation (ALE)

| Work | Modality | Contrasts | Reported foci | Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aoki et al.,2005 | PET | 3 | 1/7/12 | 10 |

| Aramaki et al.,2006 | fMRI | 2 | 18/7 | 15 |

| Blinkenberg et al.,1996 | PET | 1 | 10 | 8 |

| Boecker et al.,1998 | PET | 1 | 20 | 7 |

| Calautti et al.,2001 | PET | 4 | 10/10/4/10 | 7 |

| Catalan et al.,1998 | PET | 1 | 9 | 13 |

| Catalan et al.,1999 | PET | 1 | 12 | 13 |

| Colebatch et al.,1991 | PET | 2 | 3/8 | 6 |

| De Luca et al.,2005 | fMRI | 1 | 4 | 7 |

| Denslow et al.,2005 | fMRI | 1 | 13 | 11 |

| Fox et al.,2004 | PET | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Gelnar et al.,1999 | fMRI | 1 | 8 | 8 |

| Gerardin et al.,2000 | fMRI | 1 | 24 | 8 |

| Gosain et al.,2001 | fMRI | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Hanakawa et al.,2003 | fMRI | 1 | 25 | 10 |

| Indovina and Sanes,2001 | fMRI | 1 | 9 | 15 |

| Jancke et al.,1999 | fMRI | 6 | 2/2/2/2/2/2 | 6 |

| Jancke et al.,2000a | fMRI | 4 | 12/11/13/12 | 8 |

| Jancke et al.,2000b | fMRI | 6 | 3/3/1/2/1/2 | 11 |

| Joliot et al.,1998 | PET | 1 | 13 | 5 |

| Joliot et al.,1999 | PET/fMRI | 3 | 11/16/20 | 8 |

| Kawashima et al.,1999 | PET | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Kawashima et al.,2000 | fMRI | 1 | 10 | 8 |

| Kuhtz‐Buschbeck et al.,2003 | fMRI | 2 | 8/12 | 12 |

| Larsson et al.,1996 | PET | 1 | 14 | 8 |

| Lehericy et al.,2006 | fMRI | 3 | 8/11/27 | 12 |

| Lerner et al.,2004 | PET | 1 | 9 | 10 |

| Lutz et al.,2000 | fMRI | 2 | 17/7 | 10 |

| Mattay et al.,1998 | fMRI | 3 | 8/12/15 | 8 |

| Muller et al.,2002 | fMRI | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Ramsey et al.,1996 | PET/fMRI | 2 | 1/1 | 10 |

| Riecker et al.,2006 | fMRI | 2 | 6/8 | 10 |

| Rounis et al.,2005 | PET | 1 | 17 | 8 |

| Sadato et al.,1996 | PET | 1 | 6 | 10 |

| Sadato et al.,1997 | PET | 6 | 13/15/3/6/ 12/13 | 12 |

| Seitz et al.,2000 | fMRI | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Wilson et al.,2004 | fMRI | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| Yoo et al.,2005 | fMRI | 1 | 17 | 10 |

If more than one number is given in the column “Reported foci”, multiple experiments from the same article have been analyzed (cf. Laird et al.,2008).

Simulation analysis

In order to assess the face validity of our modification to the ALE approach we also performed ALE meta‐analyses on two simulated datasets. It should be noted that the “studies” included into these datasets do not correspond to any real data as published in the literature. Rather each study solely refers to a set of individual foci, i.e., MNI coordinates, which were generated in order to simulate situations occurring in meta‐analyses.

The first simulated dataset consists of 25 studies. Each of these studies is supposed to have investigated 12 subjects in order to avoid confounding effects of different sample sizes. For every study, we set one focus on the inferior frontal gyrus corresponding to BA 44. Hence, this region is the location of the “true” activation, which is to be revealed by the meta‐analyses. Furthermore, a single one out of the 25 studies also features an activation in the inferior parietal lobe (IPL). For this activation, however, 10 individual foci are given, corresponding to a situation where individual local maxima are listed in a very detailed fashion. This analysis aims at revealing the distinction between fixed‐ and random‐effects analyses. Fixed‐effects analyses as implemented in classical ALE assess the convergence between individual foci. It should therefore reveal a significant effect in the IPL because 10 foci cluster closely within this area. In contradistinction, this location should not become significant in a random‐effects analysis, as all of these foci were reported in the same study and the object of inference is to reveal a convergence across studies. Both methods, however, should identify the clustering of activations in the inferior frontal gyrus.

The second dataset also consists of 25 studies, and again features a true convergence of the reported activations in BA 44. Out of these 25 studies, four are assumed to have investigated 30 subjects each. Due to the higher reliability resulting from such larger samples, these four foci all cluster very tightly around a presumed true location of the effect. The remaining 21 studies, however, only examined four subjects, i.e., had very small sample sizes. Consequently, the locations of the reported foci are simulated to be more variable (due to the larger influence of sampling effects). This analysis aims at testing the explicit variance model employed in the revised ALE approach. As outlined above, the between‐subject variance enters the variance model scaled by the sample size resulting in smaller FWHMs for studies investigating larger samples. Consequently the latter studies should have increased localizing power in the ALE meta‐analysis. In the present simulation, we would hence expect that the results obtained from the revised ALE algorithm would be less influenced by the foci obtained from the smaller studies and, therefore, more confined to the location of the foci reported in the four larger studies.

To each of the individual studies in both simulated meta‐analyses, 10 further foci are added, which were randomly (and independently across studies) allocated to grey matter voxels. In real datasets, these foci would correspond to activations evoked by other components of the respective tasks. In the context of these meta‐analyses, however, they represent noise, as there is no convergence between them. Both datasets are then analyzed using the original ALE algorithm and its revised version in the same manner as the experimental data described above.

RESULTS

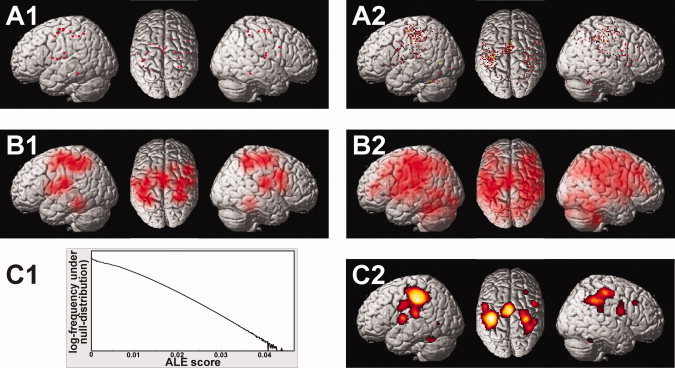

Between‐Subject Variance

There was a considerable variability in the location of the local maxima of activation between the 21 subjects analyzed in the current study (see Fig. 1). In order to quantify the uncertainty in spatial localization of the local maxima, the Euclidean distance between corresponding maxima was computed pairwise for all possible combinations, separately for each normalization procedure employed (see Fig. 2). The area‐specific mean Euclidean distances (averaged across normalizations) ranged from 7.6 mm (left caudate nucleus) to 17.6 mm (prefrontal cortex/middle frontal gyrus) (Fig. 2A). The effects of the approach used for spatial normalization on the between‐subject variance (averaged across all areas), on the other hand (Fig. 2B), was less pronounced. In particular, depending on the applied normalization procedure, the between‐subject variances ranged from 11.0 mm (Norm2EPI) to 12.1 mm (Lin2MNI152). The grand‐average Euclidean distance between corresponding maxima, averaged across all areas and normalization procedures, which will subsequently be considered the estimate of the between subject variance (EDsub) was 11.6 mm, corresponding to a FWHM of the Gaussian uncertainty model of

mm.

mm.

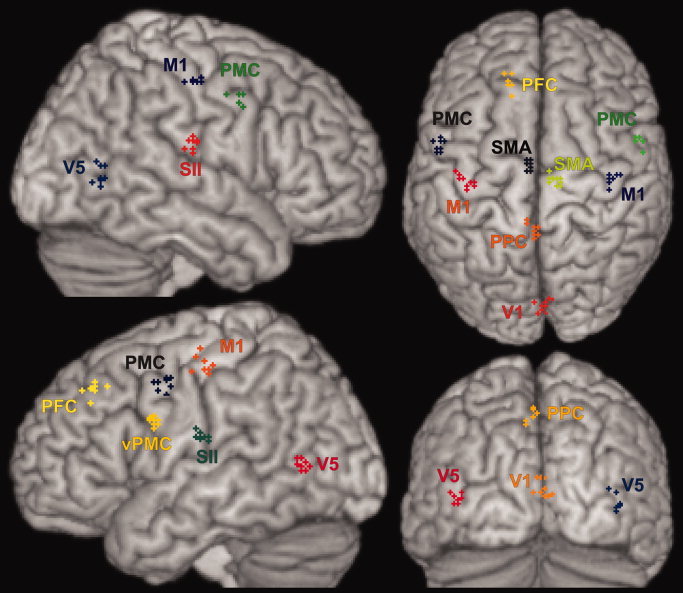

Figure 1.

Localization of the statistical maxima for the areas listed in Table II identified in the single subject analyses (N = 21). The data shown here is based on normalizing each subjects data into standard stereotaxic space using a linear transformation to the MNI152 template (Lin2MNI152, cf. Table I) and is displayed on a surface view of the MNI single subject template.

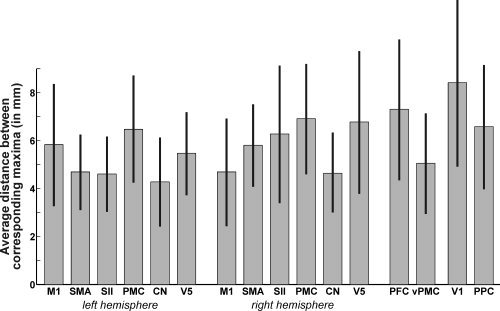

Figure 2.

Mean Euclidean distance between corresponding maxima (computed pairwise for all possible combination of group‐analyses) shown separately for each region (A: averaged over normalization approaches) and normalization procedure (B: averaged across regions). The average across all areas and normalization s, i.e., the estimate of the between subject variance (EDsub) was 11.6 mm. In A, bars denote the standard deviation across normalization approaches, in B across regions.

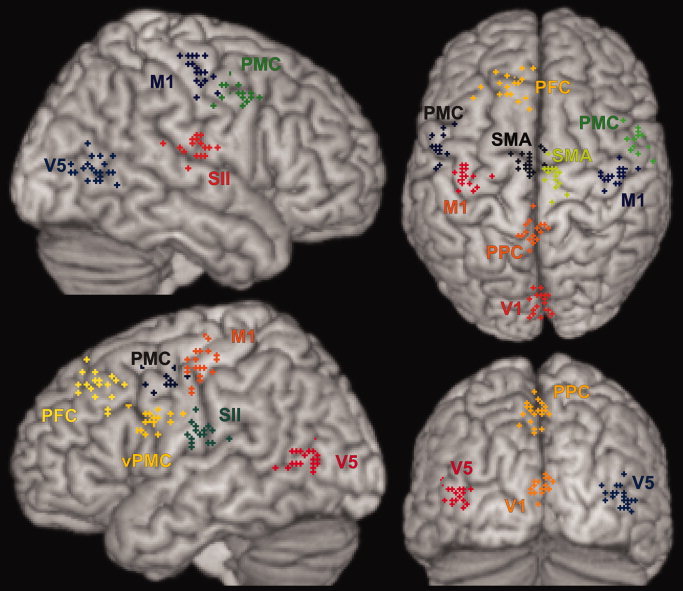

Between‐Template Variance

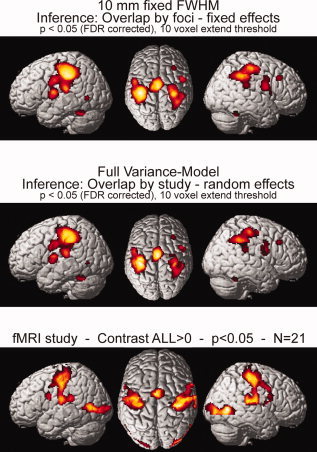

For each of the nine normalization approaches considered in this experiment, a separate group (random‐effects) analysis was computed, and linear contrasts as listed in Table II were evaluated. For illustration, Figure 3 shows surface renderings of the contrast “L > 0 ∩ R > 0”, as tested in each individual group‐analysis. It becomes evident, that although identical statistical analysis performed on the exactly same fMRI data, the results (thresholded at the same significance level) differ from each other with respect to the size and the precise location of the activated clusters of voxels. That is, the applied normalization procedure does indeed affect the results of fMRI group analysis, illustrating the need for considering the between‐template variance in meta‐analysis.

Figure 3.

Significant results for the contrast “L > 0 ∩ R > 0”, i.e., regions that were considered active independently of the moved hand at a threshold of P < 0.001 (uncorrected). Data is shown for each of the nine group analyses performed in identical fashion on the same subjects but differing in the approaches used to transform each subject's data into MNI space. All results are displayed on a surface view of the MNI single subject template. The juxtaposition of these results illustrates that in spite of identical primary data and statistical processing, the results of fMRI group analyses are indeed influenced by the applied spatial normalization. A more detailed description and in particular a quantitative assessment of these spatial normalization effects on the stereotaxic location of local maxima (equivalent to the between‐template variance in meta‐analyses) are provided in the main text.

As the present report is concerned with coordinate‐based meta‐analysis, we did not test for voxel‐wise differences between the ensuing contrast maps. In particular, while such an analysis would be interesting in its own right, it would not contribute to the quantification of the spatial uncertainty associated with stereotaxic coordinates for local maxima as reported in research papers and subjected to meta‐analyses. To quantify this uncertainty, however, is one of the major aims of the present revision to the ALE approach. Our analysis and the ensuing estimation of between‐template variance hence focused on the variability of local maxima coordinates induced by different normalization procedures.

As illustrated (see Fig. 4), the local maxima for the 16 investigated brain regions (cf. Table II) were close but clearly not identical across the nine performed analyses. Again, it has to be stressed, that the only difference between the datasets used to compute these contrasts was the applied spatial normalization. The variance in the maxima coordinates (Table IV) can hence be attributed only to between‐template variability. In order to quantify the uncertainty in the spatial localization of reported maxima induced by different normalization procedures, the between‐template variability was assessed using the coordinates for these local maxima (Table IV) as resulting from applying different spatial normalization procedures to the same original data. To this end, we computed the Euclidean distance between corresponding maxima pairwise for all possible combinations of group‐analyses (Fig. 5, Table IV). The area‐specific mean Euclidean distances ranged from 4.3 mm (left caudate nucleus) to 8.4 mm (V1). The average Euclidean distance across all areas, which will subsequently be considered the estimate of the between template variance (EDtemp), was 5.7 mm, corresponding to a FWHM of the Gaussian uncertainty model of 8.4 mm.

Figure 4.

Localization of the statistical maxima identified for the areas listed in Table II by the nine group‐analyses using the normalization approaches shown in Table I displayed on a surface view of the MNI single subject template. All group analyses were based on the same data from 21 subjects and performed in the same fashion.

Table IV.

Stereotaxic location of the local maxima identified for the 16 brain regions listed in table 2 by random‐effects group analyses of the 21 subjects depending on the normalization procedure used to transform the individual data into the MNI reference space

| Region | M1 L | SMA L | SII L | M1 R | SMA R | SII R | V1 | PCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin2MNI152 | −36/−20/54 | −6/−8/52 | −48/−16/22 | 42/−16/50 | 10/−18/50 | 46/−20/22 | 0/−90/16 | −2/−44/52 |

| Norm2MNI152 | −38/−22/50 | −4/−12/50 | −44/−22/18 | 38/−24/48 | 12/−22/50 | 46/−20/16 | 4/−86/10 | −6/−42/44 |

| Lin2Colin | −34/−20/54 | −4/−8/52 | −46/−16/18 | 44/−16/48 | 12/−18/48 | 50/−20/20 | 4/−90/16 | 0/−44/50 |

| Norm2Colin | −34/−22/52 | −4/−12/50 | −44/−18/20 | 38/−20/48 | 12/−20/48 | 46/−22/20 | 2/−88/16 | −6/−40/46 |

| Lin2EPI | −34/−22/48 | −4/−10/50 | −46/−20/18 | 38/−16/48 | 6/−18/48 | 40/−20/14 | 4/−84/6 | −2/−48/48 |

| Norm2EPI | −38/−24/52 | −4/−14/52 | −46/−22/16 | 40/−18/48 | 10/−22/48 | 42/−20/16 | 2/−86/8 | −2/−50/48 |

| Seg2TPM | −36/−20/50 | −6/−10/54 | −44/−20/18 | 38/−18/48 | 8/−18/48 | 46/−18/20 | 6/−82/6 | −2/−44/48 |

| Seg2Colin | −42/−16/56 | −6/−14/56 | −48/−20/18 | 38/−20/48 | 6/−14/54 | 42/−24/16 | −2/−84/8 | 0/−48/50 |

| Seg2TPM2Colin | −36/−20/49 | −4/−12/55 | −46/−18/17 | 38/−20/49 | 6/−20/51 | 48/−18/19 | 8/−82/7 | −2/−46/53 |

| Mean | −36/−21/52 | −5/−11/52 | −46/−19/18 | 39/−19/48 | 9/−19/49 | 45/−20/18 | 3/−86/10 | −2/−45/49 |

| ED | 5.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 6.3 | 8.4 | 6.6 |

| Region | PMC L | PMC R | CN L | CN R | V5 L | V5 R | PFC | vPMC |

| Lin2MNI152 | −52/4/44 | 54/4/42 | −18/8/24 | 20/6/24 | −46/−66/8 | 38/−66/10 | −14/26/42 | −52/2/24 |

| Norm2MNI152 | −54/−2/38 | 52/4/36 | −16/10/24 | 26/6/28 | −44/−68/6 | 42/−64/8 | −16/32/44 | −58/4/24 |

| Lin2Colin | −56/2/40 | 58/4/42 | −16/8/26 | 24/8/24 | −46/−66/8 | 42/−64/8 | −14/26/42 | −58/4/26 |

| Norm2Colin | −50/2/44 | 52/2/38 | −14/10/24 | 24/6/26 | −40/−64/8 | 42/−62/8 | −14/32/42 | −58/4/28 |

| Lin2EPI | −52/2/40 | 54/6/46 | −18/8/22 | 22/8/26 | −42/−66/2 | 42/−64/−2 | −18/38/40 | −60/4/22 |

| Norm2EPI | −54/−2/46 | 56/2/42 | −18/6/24 | 22/8/26 | −42/−70/4 | 44/−64/2 | −14/38/40 | −60/4/24 |

| Seg2TPM | −54/−4/46 | 54/4/46 | −18/10/22 | 20/8/24 | −42/−66/4 | 44/−62/2 | −16/32/40 | −60/6/26 |

| Seg2Colin | −52/−4/42 | 56/−4/42 | −20/4/24 | 18/4/26 | −44/−68/2 | 42/−68/0 | −16/34/34 | −62/2/26 |

| Seg2TPM2Colin | −52/−2/45 | 56/0/45 | −18/10/23 | 20/8/23 | −40/−64/5 | 44/−64/1 | −16/34/41 | −58/6/27 |

| Mean | −53/0/43 | 55/2/42 | −17/8/24 | 22/7/25 | −43/−66/5 | 42/−64/4 | −15/32/41 | −58/4/25 |

| ED | 6.5 | 6.9 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 5.1 |

The two lowest lines denote the mean stereotaxic location (averaged across the nine different group analyses) as well as the mean Euclidean distance (in mm) between the local maxima coordinates as resulting from the individual group analyses.

Figure 5.

Mean Euclidean distance between corresponding maxima (computed pairwise for all possible combination of group‐analyses) for each of the analyzed brain regions. The average across all areas, i.e., the estimate of the between template variance (EDtemp) was 5.7 mm.

Modified ALE Analysis

Using the estimates for between‐subject and between template variability and formula (4) listed in the methods section of this paper, the FWHM describing the uncertainty in spatial location and hence the probability distribution for each focus was computed for each experiment. The average FWHM across all experiments was 10.2 ± 0.4 mm (mean ± SD), ranging from 9.5 to 11.4 mm. ALE meta‐analysis was then performed as outlined above: First a modeled activation (MA) map was computed for each experiment from the reported foci (see Fig. 6). ALE scores for each voxel in the reference space were then computed as the union of these activation probabilities across experiments, tested against a null‐distribution reflecting a random spatial association of the MA maps across experiments and thresholded at P < 0.05 (FDR corrected) as shown in Figure 6.

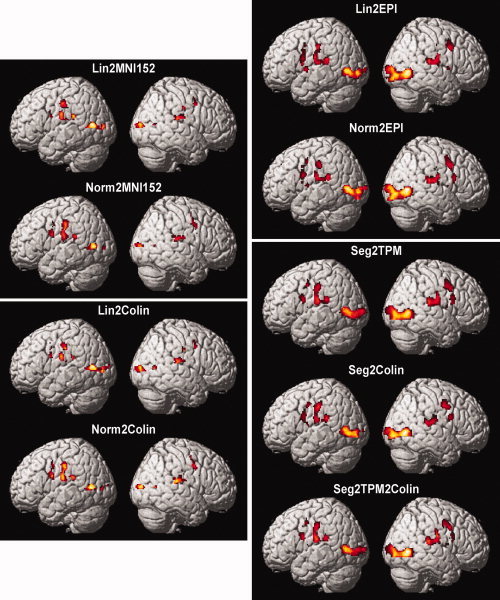

The regions, which showed a significant convergence of literature foci reported for finger‐tapping experiments, corresponded anatomically [Eickhoff et al.,2005] to the motor cortex, the dorsal and ventral premotor cortices, the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices, the cerebellum and the thalamus, all of which were activated bilaterally. In addition, left hemispheric convergence was observed in the anterior insula and the basal ganglia while right hemispheric convergence was found in the prefrontal cortex. These results are in good accordance to the well established network for the control of hand movements [e.g., Grefkes et al.,2008a; Rizzolatti and Luppino,2001; Vogt et al.,2007]. Furthermore, there is also a good agreement between the findings obtained in the meta‐analysis and the main effect (L + R > 0, as studies included in the meta‐analysis reported coordinates for the movement of either hand) calculated for the fMRI data described in this paper (see Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Comparison of the results obtained for the coordinate‐based meta‐analysis as performed using the classical ALE algorithm (10 mm FWHM, fixed‐effects inference, no grey‐matter mask) and the new approach outlined in the present paper (FWHM based on empirically derived variance mode, random‐effects inference, grey matter mask). For comparison the results obtained in the present fMRI study for the contrast “L + R > 0” (as also the studies included in the meta‐analysis reported coordinates for the movement of either hand). All data is displayed on a surface view of the MNI single subject template.

To evaluate the impact of the two theoretically motivated changes to the ALE algorithm proposed in this paper (explicit modeling of uncertainty, testing for convergence across experiments), we also analyzed the same finger‐tapping dataset using the classical ALE algorithm (see Fig. 7). A comparison of the significant activations yielded by either approach showed that the results were very virtually identical across methods. In particular, no analysis revealed any activation not displayed by the other method (indicative of a higher sensitivity) nor did we observe a diverging pattern of ALE peak locations. This implicates, that the modifications proposed here do not lead to a decreased sensitivity of the analysis in spite of the more rigorous random‐effects approach. Also, there was a good correspondence between the regions which became significant in the meta‐analysis of finger‐tapping experiments and those which were activated when testing for the main effect of single fist opening‐closing movements in the fMRI study reported in the present paper. This corroboration of meta‐analysis results by fMRI data further supports the validity of the proposed approach.

Simulation Analysis

The comparative analysis of the two simulated datasets using the classical ALE algorithm and its revised version then clearly pinpointed the advantages of the modified approach.

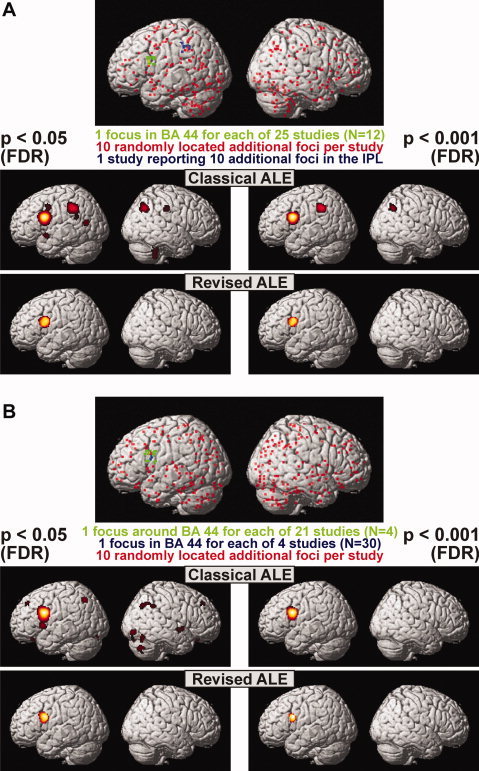

For the analysis of the first dataset (25 studies showing a focus in BA 44, and only one study reporting 10 additional foci in the inferior parietal lobe), both ALE approaches reliably detected the inferior frontal activation focus at P < 0.05 and P < 0.001 (FDR‐corrected). Only the classical (fixed‐effects) algorithm, however, indicated an additional significant convergence in the inferior parietal lobe consistent with the location of the additional foci reported in one of the studies. Importantly, this activation is entirely consistent with the definition and aim of fixed‐effects analyses, i.e., to find significant convergence across foci (Fig. 8A). However, given that all foci converging in this region were derived from one study only (and were hence not present in the remaining 24 studies), this simulated analysis also demonstrates the major drawback of fixed‐effects meta‐analyses, i.e., their strong tendency to be dominated by one or a few individual studies. In contrast, the revised random‐effects approach to ALE did not yield any significance for this region (P > 0.05). Moreover, the simulations also revealed that the fixed‐effects analyses were somewhat more sensitive to noise as introduced by adding 10 foci to each study, which were randomly located across the grey matter. While it should be noted, that 5% false‐positives are expected when thresholding at a FDR corrected significance level of P < 0.05, activation outside of BA 44 (i.e., the true convergence of the simulated foci) was not observed in the more conservative random‐effects approach.

Figure 8.

Results of the two simulated ALE analyses. The dataset examined in panel (A) consisted of 25 studies (12 subjects each) each featuring one focus in BA 44 and 10 randomly distributed additional foci. Moreover, a single study reported 10 foci in the inferior parietal lobule. Classical ALE analysis indicated significance for both regions (and locations of unintentional convergence between the random foci). In turn, the revised random‐effects approach revealed only the inferior frontal gyrus to have a true convergence between foci from different experiments. The dataset examined in panel (B) consisted of four studies investigating 30 subjects showing well localized foci in BA 44 and 21 studies investigating four subjects featuring more variable foci (each study also contained 10 randomly distributed foci). As hypothesized from the scaling of the FWHM by the sample size, the significant activation was more confined when the revised approach was used, confirming that the revised approach does indeed give higher localizing power to larger and hence more representative studies. As in the first dataset, classical ALE analysis but not the more conservative random‐effects approach also revealed spurious convergence between the random foci.

The ALE analysis of the second dataset featuring four tightly clustered foci (from studies investigating larger samples), and 21 more variable foci (from studies with relatively small sample sizes) showed that both algorithms correctly identified the respective convergence of the data in the inferior frontal gyrus (Fig. 8B). As hypothesized from the scaling of the FWHM by the sample size, however, the significant activation was more confined when the revised approach was used. This observation, which was independent of the applied threshold, indicates that the proposed uncertainty model reasonably weights the localizing power of individual studies in favor for those with larger sample sizes. Similar to the results of the first simulated dataset, classical ALE meta‐analysis also showed significant results in other parts of the brain, while such spurious convergence was rejected by the modified ALE algorithm.

In summary, the simulated analyses and the meta‐analysis of real fingertapping experiments suggest that the revised ALE approach features a higher specificity than the classical algorithm employing a fixed‐effects model and a predefined FWHM, while sensitivity is comparable with that of previous ALE algorithms.

DISCUSSION

In this report we outlined a revision of the ALE algorithm for coordinate‐based neuroimaging meta‐analyses addressing several shortcomings of the original implementation: By providing empirical estimates for between‐subject and between‐template variability, the subjective choice of FWHM for the Gaussian probability distributions could be replaced by a quantitative uncertainty model. The inference on the ensuing ALE maps was constrained to grey matter voxels and modified to reflect a null‐hypothesis of random spatial association between experiments (random‐effects) rather than foci (fixed‐effects).

Spatial Variability of Neuroimaging Results

In spite of high number of functional neuroimaging experiments in recent years, surprisingly few studies investigated between‐subject variability using current imaging protocols [la‐Justina et al.,2008; Otzenberger et al.,2005; Seghier et al.,2004] and none provided quantitative estimates of the spatial uncertainty associated with reported stereotaxic coordinates. Earlier work, comparing the spatial uncertainty associated with fMRI and PET images, however, found these to be comparable between both imaging techniques. In these reports, the average inter‐subject distance of functional activations was generally estimated in the range of 10–20 mm [Bookheimer et al.,1997; Clark et al.,1996; Fox et al.,1999,2001; Hasnain et al.,1998; Xiong et al.,2000]. These studies hence suggested a somewhat higher between‐subject variance as opposed to our current data, which may be attributable to the fact that more recent neuroimaging studies trend to employ smaller voxel sizes and that normalization procedures have generally become more refined over the course of continued development.

There have already been quantitative evaluations of inter‐subject realignment using the dispersion of anatomical landmarks after spatial normalization [Ardekani et al.,2005; Grachev et al.,1999; Hammers et al.,2002; Hellier et al.,2003]. In these studies, the residual anatomical uncertainty was different between regions (lower for subcortical regions) but generally estimated in the range of 6–9 mm average ED between corresponding landmarks. While we could confirm the generally lower variability in subcortical regions, the inter‐subject variability of local BOLD maxima was clearly higher than that of anatomical landmarks. Our results hence imply that between‐subject variability in functional neuroanatomy can only partially be explained by the inexactness of spatial normalization. This argument is further supported by the observation that functional variability was similar for all normalization approaches tested. It seems, therefore, that the observed dispersion of local maxima is a direct reflection of the microstructural variability of the cortex rendering the location of cortical areas partially independent of cortical landmarks [Amunts et al.,2004; Eickhoff et al.,2006b; Grefkes et al.,2001; Malikovic et al.,2007; Rottschy et al.,2007]. Our analysis moreover showed that the between‐subject variance was inhomogeneous across brain regions. The smallest variability was found for the caudate nucleus, while the PFC was particularly variable. It must be assumed that both biological and technical effects contribute to these differences: The functional neuroanatomy of regions like the PFC is more variable due to pronounced inter‐individual differences in the relative size and shape of the different areas jointly occupying this part of the brain. This increased variability of “higher” cortical regions, compared to primary areas, has been well documented in neuroimaging experiments and histological mapping studies [Caspers et al.,2008; Hasnain et al.,1998; Scheperjans et al.,2007; Walters et al., in press; Watson et al., 1992; Xiong et al.,2000 Zilles et al.,2003]. The less conserved cortical organization may provide an important biological basis for the observation that some regions show a higher inter‐individual variability in the location of functional activations. From this line of argument, the high variability of M1 activations seems surprising at first. It may, however, be explained by between‐subject variability in the topological arrangement of different body parts in this somatotopically organized area. In summary, there is hence clear evidence for a biological underpinning of the inter‐regional differences in variability. It should, however, also be considered that some particularly variable areas (like the PFC) are at the same time located in brain regions where normalization into standard space is usually less reliable due to the absence of prominent anatomical landmarks and marked inter‐individual differences in cortical folding pattern. In contrast, macroanatomically distinct and less variable structures like the caudate nucleus may be normalized more reliably by automated registration algorithms. This was shown by previous analyses of the registration accuracy for various cortical and subcortical landmarks, showing best accuracy for subcortical structures and those located close to the major cortical landmarks [Grachev et al.,1999; Hellier et al.,2003]. Some of the differences evident in Figure 2 may hence not be biological in nature but result from in local homogeneities in image registration precision.

Uncertainty Modeling

In the original ALE approach, literature foci were modeled by Gaussian probability distributions of identical, user specified width [Laird et al.,2005; Turkeltaub et al.,2002]. This approach was now modified in favor of a more flexible and principled solution. Here the size of the modeled probability distribution that is to reflect the “true” location of a reported activation is based on the spatial uncertainty associated with each experiment. In order to explicitly model this uncertainty, empirical estimates of both between‐subject and between‐template (inter‐laboratory) were provided in the present study. These were subsequently used to model the spatial uncertainty associated with each particular set of coordinates when performing the ALE computation. It should be noted, that the current algorithm models the spatial uncertainty associated with the foci reported in a particular experiment using the same Gaussian distribution widths across all brain regions. Theoretically, however, it would be very straightforward to incorporate nonstationary variances in the proposed model in order to account for regionally specific uncertainties by substituting the (grand mean) Euclidean distances in formula (1) by local estimates depending on the position of a particular focus. In practice, however, one major obstacle renders this approach unfeasible at present: The computation of regionally specific uncertainty models requires empirical data for each region or ideally every voxel of the reference space. In the present study, we demonstrated how estimates for the between‐subject and between‐template variances could be derived by investigating 14 cortical and 2 subcortical brain regions. To our knowledge, this analysis constitutes the most comprehensive assessment of variance associated with functional imaging data to date. It is nevertheless still clearly not sufficient to generate a whole‐brain variance map. Such a map, however, would be a prerequisite for a more flexible model representing regionally specific uncertainties. Given an adequate amount of empirical data on the spatial variability of functional imaging results in various brain regions (which could be derived from a series of experiments employing a similar approach as described here), however, such a map could be constructed and then readily be integrated into the proposed framework.

While the motivation for modeling between‐template variance is straightforward (coordinates from any of the normalization approaches described here would be reported as “MNI space”), including the between‐subject variance in meta‐analyses of group results may seem counterintuitive. The main reason for this approach is the small sample size in typical neuroimaging studies and the resulting influence of unsystematic sampling errors on the localization of group results. It should moreover be noted, that in the proposed model the between‐subject variance is inverse scaled by the (square root of the) sample size. This accounts for the notion, that an activation reported in a study examining a small sample size is potentially less reliable as these results are more susceptible to individual outliers (in a single case, the added uncertainty equal between‐subject variance). Conversely, if the sample size increases the sampling error and hence the uncertainly associated with a given focus will decrease.

Using the outlined model, foci derived from studies examining many subjects will hence be modeled by tighter distributions as compared to those foci that were reported in experiments investigating fewer subjects. Consequently, foci provided by the latter studies will be more blurred and have less localizing impact on the ALE maps. In other words, studies that provide the most reliable information about the location of a particular process also receive the highest weight in the meta‐analysis. Modeling the reduced spatial uncertainty in larger studies may therefore represent a well‐motivated approach to weighting the sample size for coordinate‐based meta‐analyses. The comparative ALE meta‐analyses of simulated datasets using both the original and the revised ALE approach clearly showed that the revised ALE model does indeed give a higher localizing power to larger studies (cf. Fig. 8B). Assuming that larger studies are less susceptible to sampling errors and hence report local maxima closer to their true location (as in our simulations), we suggest that this modification should result in a higher validity of coordinate‐based meta‐analysis results. In contrast to the simulated datasets, differences between both algorithms were inconspicuous in the analysis of the real finger‐tapping data. This observation may predominantly be attributable to the rather small range of sample sizes among the analyzed experiments. In particular, 28 of the 37 included experiments were based on the analysis of groups comprising between 8 and 13 subjects. In comparison to the more extreme situation in the simulated data, the influence of the specifically computed uncertainty was consequently much lower. The second major advantage of the proposed uncertainty model, however, also pertains to the exemplary analysis presented here: Unlike previous algorithms using ALE or kernel density estimation (KDE), the revised meta‐analysis approach does not require the kernel width to be subjectively specified by the user but rather makes use of an (empirical) model for spatial uncertainty.

Random Effects Versus Fixed‐Effects Analyses

In the original ALE algorithm permutation testing is performed by randomly relocating foci across the brain resulting in a null‐distribution for above‐chance clustering of individual activations. The object of meta‐analyses, however, should pertain to above chance clustering between experiments rather than a convergence across individual foci. This difference becomes most evident, when considering, that in some studies several different coordinates for local maxima within the same (larger) activation may be reported. In this case, an observed above‐chance clustering of these coordinates may not indicate convergence between (independent) experiments, but just a clustering of foci within a single one of the included experiments. To focus on the convergence of information across studies the (noninformative) clustering between individual foci reported for any given experiment should hence be considered fixed. This approach has been implemented in the current version of the ALE algorithm by computing a “modeled” activation (MA) volume for each individual experiment as the sum of the Gaussian probability distribution for its foci. ALE scores are then obtained by the (voxel‐wise) union of these MA maps across studies. To compute the appropriate null‐distribution, one random voxel is drawn from each MA map (discarding its spatial location), and an ALE score is computed. By repeating this procedure, a null‐distribution is constructed reflecting a random spatial association between different studies. Comparing the “true” ALE score to this distribution then allows focusing inference only on convergence between studies while preserving the relationship between individual foci within each study. Critically, this modification is conceptually equivalent to the distinction between a fixed‐effect analysis, allowing generalization only to the studies included in the analysis, and a random‐effects model, allowing an inference about the population of studies from which the analyzed experiments were drawn. In the current paper, both approaches were compared to each other based on real (meta‐analysis of finger tapping experiments) and simulated datasets. Interestingly, the analysis of the finger tapping data did not show pronounced differences between both algorithms. These congruent results indicate that the activations revealed by the classical ALE analysis of this dataset were predominantly driven by random‐effects (i.e., convergence between studies). In the simulation analysis, however, we also tested a case where the assumption that a convergence between foci is equivalent to a convergence between experiments was explicitly violated. In particular, we simulated a dataset, which contained a region of strongly converging foci across different experiments as well as a second region, which also showed a strong convergence between foci. Critically, however, all of these foci were derived from the same original experiment. That is, there was a dissociation between a fixed‐effects convergence across foci (which was present) and a random‐effects convergence across studies (which was absent). Comparative analysis then showed, that the classical ALE approach indicated significance for both regions (as well as for other locations of accidental convergence between the randomly allocated foci). In contrast, the random‐effects approach described here revealed the inferior frontal gyrus as the only region where a true convergence between foci reported in different experiments occurred. This (simulated) example highlights the more conservative approach taken by random‐effects analyses and provides a strong argument for the increased specificity (though apparently not reduced sensitivity) achieved by the revision of the classical ALE algorithm.

An alternative technique allowing random‐effects inference in coordinate‐based meta‐analysis is KDE. Both KDE and ALE aim at identifying locations where reported coordinates show a higher convergence as expectable by chance, but they do so using different approaches. ALE investigates how much the location probabilities modeled for each study overlap in different voxels. KDE, on the other hand, assesses how many foci are reported close to any individual voxel [Wager et al.,2007]. The concept of RDFX‐analyses is nevertheless very similar between the algorithm described here and multi‐level kernel density estimation (MKDE). In particular, in both approaches RDFX analyses are based on summarizing all foci reported for any given study in a single image (the “modeled activation” (MA) map in ALE and “comparison indicator maps” (CIM) in MKDE). These are then combined across studies. Inference is subsequently sought on those voxels where MA maps (ALE) or CIMs (MKDE) overlap stronger as would be expected if there were a random spatial arrangement, i.e., no correspondence between studies. Both approaches also use a weighting for the study size based on the square root of the number of subjects. While this factor is multiplicative in KDE, however, it influences the obtained uncertainty model in our approach (cf. formula 3). Other differences pertain to the permutation algorithm (randomly relocating cluster centers versus combining randomly selected voxels) and the fact, that MKDE uses a discount‐factor for fixed‐effect studies, which is not the case in the approach described here.

Restriction of Analysis Space

Neuroimaging using fMRI and PET is based on hemodynamic changes initiated by vasodilatory mediators released by cortical and subcortical grey matter under increased computational and metabolic demand [Buxton et al.,2004; Fox and Raichle,1986; Logothetis,2003]. Conversely, white matter, consisting only of fibre bundles, may not be expected to show task evoked changes in blood flow. Activations should hence be confined to cortical and subcortical grey matter, even when considering the spatial dispersion of hemodynamic signals [Buxton et al.,2004; Fox and Raichle,1986; Logothetis,2003]. This assumption was retrospectively confirmed by analyzing the location of 35,196 activation foci included in the BrainMap database. After transformation into MNI space, 98.5% of these foci were located within the grey matter ROI used in our algorithm.

The fact that “true” activations occur almost exclusively in grey matter has important implications for the applied permutation test. In particular, if all intracranial voxels were to be included in this procedure, many of them would be drawn from regions where activation is known to be absent, like the ventricles or the deep white matter. Evidently, these regions will show values close to zero in their MA maps. Hence, the null‐distribution will become left skewed and the significance of the experimental ALE scores is overestimated. To correct for this bias and to provide a null‐distribution closer to the experimental situation, the analysis space of the modified ALE algorithm was restricted to those voxels of the MNI space, where the probability for grey matter was >10%.

CONCLUSIONS

The proposed revision of the ALE algorithm overcomes several important drawbacks of the original implementation, namely the need for a manually defined width of the localization probability distribution, the anatomically uninformed analysis space and its fixed‐effects inference. In order to address the first shortcoming, we provided empirical estimates for between‐subject and between‐template variance of neuroimaging foci. The subsequent analysis was then revised in order to test for convergence between studies (random‐effects) rather than foci (fixed‐effects). This was achieved by a modification of the permutation procedure, which now reflects a null‐distribution of a random spatial association between studies not between foci. Importantly, this change to a random‐effects approach now allows generalization of the results to the entire population of studies from which the analyzed one were drawn. Finally, rather than analyzing each voxel in the reference space, including those in deep white matter or the ventricles, the revised ALE algorithm now works with an explicit grey matter mask, solving the problem of an anatomically uninformed analysis space.

Importantly, we could show that the results derived from this novel, theoretically motivated algorithm to ALE meta‐analysis are comparable to those obtained from previous implementations and experimental fMRI data. Simulation analysis confirmed this observation and demonstrated that the revised approach has a better specificity than classical ALE analysis while retaining the high sensitivity of the previous approach. Incorporated into the BrainMap application GingerALE, the revised ALE algorithm will thus provide an improved tool for conducting coordinate‐based meta‐analyses on functional imaging data, which in turn should become of growing importance for summarizing the multitude of results obtained by neuroimaging research.

Acknowledgements

K.Z. acknowledges funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KFO‐112) and the Volkswagenstiftung. A.R.L. and P.T.F. were supported by the Human Brain Project of the NIMH (R01‐MH074457‐01A1).

REFERENCES

- Amunts K,Weiss PH,Mohlberg H,Pieperhoff P,Eickhoff S,Gurd J,Marshall JC,Shah NJ,Fink GR,Zilles K ( 2004): Analysis of neural mechanisms underlying verbal fluency in cytoarchitectonically defined stereotaxic space—The roles of Brodmann areas 44 and 45. Neuroimage 22: 42–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T,Tsuda H,Takasawa M,Osaki Y,Oku N,Hatazawa J,Kinoshita H ( 2005): The effect of tapping finger and mode differences on cortical and subcortical activities: A PET study. Exp Brain Res 160: 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramaki Y,Honda M,Okada T,Sadato N ( 2006): Neural correlates of the spontaneous phase transition during bimanual coordination. Cerebral Cortex 16: 1338–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardekani BA,Guckemus S,Bachman A,Hoptman MJ,Wojtaszek M,Nierenberg J ( 2005): Quantitative comparison of algorithms for inter‐subject registration of 3D volumetric brain MRI scans. J Neurosci Methods 142: 67–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J,Friston KJ ( 2003) Rigid body registration In: Frackowiak RS,Friston KJ, Frith CD, Dolan RJ, Price CJ, Ashburner J, Penny WD, Zeki S, editors. Human Brain Function, 2 ed. San Diego: Academic Press; pp 635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Blinkenberg M,Bonde C,Holm S,Svarer C,Andersen J,Paulson OB,Law I ( 1996): Rate dependence of regional cerebral activation during performance of a repetitive motor task: A PET study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 16: 794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boecker H,Dagher A,Ceballos‐Baumann AO,Passingham RE,Samuel M,Friston KJ,Poline J,Dettmers C,Conrad B,Brooks DJ ( 1998): Role of the human rostral supplementary motor area and the basal ganglia in motor sequence control: Investigations with H2 15O PET. J Neurophysiol 79: 1070–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer SY,Zeffiro TA,Blaxton T,Malow BA,Gaillard WD,Sato S,Kufta C,Fedio P,Theodore WH ( 1997): A direct comparison of PET activation and electrocortical stimulation mapping for language localization. Neurology 48: 1056–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth JR,Wood L,Lu D,Houk JC,Bitan T ( 2007): The role of the basal ganglia and cerebellum in language processing. Brain Res 1133: 136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton RB,Uludag K,Dubowitz DJ,Liu TT ( 2004): Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. Neuroimage 23 ( Suppl 1): S220–S233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calautti C,Serrati C,Baron JC ( 2001): Effects of age on brain activation during auditory‐cued thumb‐to‐index opposition: A positron emission tomography study. Stroke 32: 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspers S,Eickhoff SB,Geyer S,Scheperjans F,Mohlberg H,Zilles K,Amunts K ( 2008): The human inferior parietal lobule in stereotaxic space. Brain Struct Funct 212: 481–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan MJ,Honda M,Weeks RA,Cohen LG,Hallett M ( 1998): The functional neuroanatomy of simple and complex sequential finger movements: A PET study. Brain 121(Pt 2): 253–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalan MJ,Ishii K,Honda M,Samii A,Hallett M ( 1999): A PET study of sequential finger movements of varying length in patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain 122 (Pt 3): 483–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark VP,Keil K,Maisog JM,Courtney S,Ungerleider LG,Haxby JV ( 1996): Functional magnetic resonance imaging of human visual cortex during face matching: A comparison with positron emission tomography. Neuroimage 4: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colebatch JG,Deiber MP,Passingham RE,Friston KJ,Frackowiak RS ( 1991): Regional cerebral blood flow during voluntary arm and hand movements in human subjects. J Neurophysiol 65: 1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M,Smith S,De Stefano N,Federico A,Matthews PM ( 2005): Blood oxygenation level dependent contrast resting state networks are relevant to functional activity in the neocortical sensorimotor system. Exp Brain Res 167: 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denslow S,Lomarev M,George MS,Bohning DE ( 2005): Cortical and subcortical brain effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)‐induced movement: An interleaved TMS/functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry 57: 752–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB,Stephan KE,Mohlberg H,Grefkes C,Fink GR,Amunts K,Zilles K ( 2005): A new SPM toolbox for combining probabilistic cytoarchitectonic maps and functional imaging data. Neuroimage 25: 1325–1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB,Amunts K,Mohlberg H,Zilles K ( 2006a): The human parietal operculum. II. Stereotaxic maps and correlation with functional imaging results. Cerebral Cortex 16: 268–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB,Schleicher A,Zilles K,Amunts K ( 2006b): The human parietal operculum. I. Cytoarchitectonic mapping of subdivisions. Cerebral Cortex 16: 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AC,Kamber M,Collins DL,MacDonald D ( 1994): An MRI based probabilistic atlas of neuroanatomy In: Shorvon S,Fish D, Andermann F, Bydder GM, editors. Magnetic Resonance Scanning and Epilepsy. New York: Plenum Press; pp 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MJ,Laird AR,Egan GF ( 2005): Brain activity associated with painfully hot stimuli applied to the upper limb: A meta‐analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 25: 129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feredoes E,Postle BR ( 2007): Localization of load sensitivity of working memory storage: Quantitatively and qualitatively discrepant results yielded by single‐subject and group‐averaged approaches to fMRI group analysis. Neuroimage 35: 881–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT,Raichle ME ( 1986): Focal physiological uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism during somatosensory stimulation in human subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83: 1140–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT,Huang AY,Parsons LM,Xiong JH,Rainey L,Lancaster JL ( 1999): Functional volumes modeling: Scaling for group size in averaged images. Hum Brain Mapp 8: 143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT,Huang A,Parsons LM,Xiong JH,Zamarippa F,Rainey L,Lancaster JL ( 2001): Location‐probability profiles for the mouth region of human primary motor‐sensory cortex: Model and validation. Neuroimage 13: 196–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT,Narayana S,Tandon N,Sandoval H,Fox SP,Kochunov P,Lancaster JL ( 2004): Column‐based model of electric field excitation of cerebral cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 22: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelnar PA,Krauss BR,Sheehe PR,Szeverenyi NM,Apkarian AV ( 1999): A comparative fMRI study of cortical representations for thermal painful, vibrotactile, and motor performance tasks. Neuroimage 10: 460–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR,Lazar NA,Nichols T ( 2002): Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. Neuroimage 15: 870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerardin E,Sirigu A,Lehericy S,Poline JB,Gaymard B,Marsault C,Agid Y,Le BD ( 2000): Partially overlapping neural networks for real and imagined hand movements. Cerebral Cortex 10: 1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosain AK,Birn RM,Hyde JS ( 2001): Localization of the cortical response to smiling using new imaging paradigms with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg 108: 1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grachev ID,Berdichevsky D,Rauch SL,Heckers S,Kennedy DN,Caviness VS,Alpert NM ( 1999): A method for assessing the accuracy of intersubject registration of the human brain using anatomic landmarks. Neuroimage 9: 250–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C,Geyer S,Schormann T,Roland P,Zilles K ( 2001): Human somatosensory area 2: Observer‐independent cytoarchitectonic mapping, interindividual variability, and population map. Neuroimage 14: 617–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C,Eickhoff SB,Nowak DA,Dafotakis M,Fink GR ( 2008a): Dynamic intra‐ and interhemispheric interactions during unilateral and bilateral hand movements assessed with fMRI and DCM. Neuroimage 41: 1382–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefkes C,Nowak DA,Eickhoff SB,Dafotakis M,Kust J,Karbe H,Fink GR ( 2008b): Cortical connectivity after subcortical stroke assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 63: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammers A,Koepp MJ,Free SL,Brett M,Richardson MP,Labbe C,Cunningham VJ,Brooks DJ,Duncan J ( 2002): Implementation and application of a brain template for multiple volumes of interest. Hum Brain Mapp 15: 165–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanakawa T,Immisch I,Toma K,Dimyan MA,Van GP,Hallett M ( 2003): Functional properties of brain areas associated with motor execution and imagery. J Neurophysiol 89: 989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]