SUMMARY

Objective

To examine the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms burden and disability in cognitively impaired older Latinos.

Methods

Subjects in the cross-sectional study were 95 cognitively impaired (both demented and non-demented) non-institutionalized Latino elderly participating in an epidemiological cohort study and their family caregivers. Care recipient neuropsychiatric symptoms (Neuropsychiatric Inventory) and level of functional impairment (i.e. impairment in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living) were assessed through interviews with family caregivers.

Results

Both NPI total score and NPI depression subscale score were significantly associated with disability before and after controlling for potential confounding variables. The strength of the association between higher neuropsychiatric symptom levels and higher disability was similar for both the cognitively impaired not demented and demented groups.

Conclusions

Neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with increased disability in a community sample of cognitively impaired Latino elderly. More effective identification and treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms may improve functioning in older Latinos and reduce health disparities for this population.

Keywords: neuropsychiatric symptoms, disability, Latinos, dementia, cognitively impaired not demented

INTRODUCTION

Latinos with dementia (Hinton et al., 2003; Sink et al., 2004; Ortiz et al., 2006) and those who are cognitively impaired but not demented (Hinton et al., 2003) have higher rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms compared to white non-Hispanics, yet how these symptoms impact the functioning of older Latinos is not known. Understanding the factors that generate disability in cognitively impaired older Latinos, a large and growing segment of the US elderly population, is important to clarify disparities in the ‘burden’ of dementia among older Latinos and to improve care.

In primarily Caucasian samples, neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in both dementia (Mega et al., 1996; Frisoni et al., 1999; Lyketsos et al., 2002) and MCI (Lyketsos et al., 2002; Feldman and McDonald, 2004; Geda et al., 2004). Studies of the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and disability are based on primarily Caucasian samples. Prior studies have found specific neuropsychiatric symptoms to be associated with disability. Depression severity, for example, has been fairly consistently linked to functional disability (Lenze et al., 2005; van Gool et al., 2005; Stein et al., 2006). Depression can have direct effects on both cognitive function (Rosenstein, 1998) and functional status (Espiritu et al., 2001; Mehta et al., 2002; De Ronchi et al., 2005) leading to ‘excess disability’ (i.e. disability beyond what may be expected based on level of cognitive functioning alone). Other neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy and behavioral disorders (i.e. hallucinations, agitation) have also been associated with disability, although less consistently than depression (Norton et al., 2001; Boyle et al., 2003; Tran et al., 2003).

This study examined the association between neuropsychiatric symptom severity and disability in a community sample of cognitively impaired Latino elderly participating in a longitudinal study of cognitive decline and disability. We hypothesize that increased neuropsychiatric symptom severity would be associated with increased functional disability. Additional, exploratory analyses were conducted to determine if the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptom severity and disability was similar in cognitively impaired not demented and demented sub-groups.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants

As previous described (Hinton et al., 2003), subjects were cognitively impaired (both demented and non-demented), non-institutionalized Latino elderly enrolled in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging (SALSA) and their informal caregivers. SALSA is a prospective epidemiological cohort study investigating the prevalence and incidence of dementia among 1789 older Latinos in the Sacramento area that began in 1998 (Haan et al., 2003). At inception SALSA participants were: (1) self-identified as Latino or Hispanic; (2) age 60 or above; (3) Spanish or English speakers; and (4) living in a non-institutionalized setting.

In SALSA, cognitive impairment at baseline was assessed in five steps: (1) screening using the Modified Mini-Mental State Exam, or 3MS (Teng and Chui, 1987) and a word-list learning test that is part of a battery of psychometrically matched English and Spanish-language neuropsychological assessment instruments (Mungas et al., 2000); (2) subjects below the 20th percentile (education, age, gender, and language adjusted) on either screening test and a random sub-sample of those scoring above the thresholds were referred for testing with five other neuropsychological tests; (3) subjects scoring below the 10th percentile on one or more neuropsychological tests and showing evidence of functional decline on a standardized instrument, the IQCODE (Jorm, 1994), were referred for neurological examination; (4) all subjects undergoing a neurological examination were case adjudicated by a team of neurologists and a neuropsychologist to determine the presence or absence of dementia according to DSM-III-R criteria; and (5) subjects meeting criteria for dementia were referred for an MRI and then case adjudicated again to determine their dementia subtype.

This study was ancillary to SALSA and included elderly with dementia and who were cognitively impaired but not demented (Hinton et al., 2003). Because we were initially interested in caregiving to cognitively impaired Latinos, we drew a sample consisting of all SALSA elderly with dementia, all SALSA participants who were referred for clinical exam but were found not to be demented, and a random sub-sample of those who scored below the 20th percentile but were not referred for neurological examination. For the purposes of this study, the CIND group is defined as the latter two sub-samples (i.e. subjects who scored below the 20th percentile on either of cognitive screening tests but were not referred for further examination as well as all subjects who were referred for examination but were determined not to be demented).

Procedures

Two interviews were conducted: (1) an initial in-home interview with the cognitively impaired elderly (or a proxy) that included a standardized set of questions to identify their primary, informal caregiver, followed by (2) a semi-structured interview with the primary informal caregiver. All interviews were conducted in either Spanish or English by a bilingual research assistant trained by the PI (LH). The study interviews were conducted from November of 1999 through August of 2000.

Measures

Neuropsychiatric disturbances were assessed by the neuropsychiatric symptom inventory or NPI (Cummings et al., 1994). The instrument was administered to caregivers, who were asked to rate the presence, frequency, and severity of ten symptom domains during the previous month: depression, anxiety, apathy, euphoria, aggression, irritability, disinhibition, hallucinations, delusions, and abnormal motor activity. In the present study, a version developed, field-tested, and validated in Spain (Vilalta-Franch et al., 1999) was further refined through a translation and back-translation process to ensure appropriateness for use in Mexican-Americans. For each NPI item, caregivers rate frequency on a scale of 1 to 4 and severity on a scale of 1 to 3 (or ‘0’ if the symptom is absent). To generate a score for each individual symptom, the frequency and severity score are multiplied, generating a range of 0 to 12. The total NPI score is the summed scores across individual symptoms (range 0 to 120).

Activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) were measured using a standard Likert-type scale (Lawton and Brody, 1969; Katz et al., 1963). Subject’s caregiver were queried about the care recipient’s ability to perform 13 common activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). For each item, the caregiver was asked whether the care recipient didn’t need any help (0), needed some help (1) or needed help all the time (2). For the purposes of analysis, activities of daily living were scored ‘0’ if the care recipient didn’t need any help and ‘1’ if at least some help was needed. Scale items were then summed yielding a range of 0–13.

The Modified Mini Mental State Exam or 3MS (Teng and Chui, 1987) is a global measure of cognitive functioning and is based on a 100-point scale that was designed to expand the range of measurement and increase the sensitivity of the MMSE (Folstein et al., 1975). Data on care recipient sociodemographics, 3MSE (range 0–100), and the presence or absence of dementia based on DSM-III-R criteria (as described above) were drawn from the SALSA database.

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analysis revealed that some measures departed from normality. For instance, the NPI total score was skewed toward the right with a large number of zeroes. Accordingly, non-parametrics (i.e. Mann–Whitney U-test and Spearman correlation) were used to quantify the strength of bivariate relationships. The bivariate relationships between the total ADL score on the one hand and the NPI total scale, the NPI depression subscale, the total 3MS scale, and age and other variables were determined separately for the demented group and the CIND group and for the sample as a whole.

Subsequently, multiple regression models were fit with total ADL score as the outcome variable. For the multiple regression models, variables other than NPI score were included if associated with disability at the p <0.10 level. This was done to confirm that bivariate correlations could not have resulted merely from both variables being associated with a third variable in the current data. For regression analyses, age was centered by subtracting 75 (sample median age) from care recipient age (i.e. age-75).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Characteristics of the 95 subjects who participated in this study are presented in Table 1. Fifty-four were female, 38 demented, 20 had had a stroke, and 38 had diabetes. Ages ranged from 60–97 (mean 74, SE 0.75). Mean years of formal education in this sample was 5.0 years.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| Subject characteristics | CIND (n = 57) | Dementia (n = 38) | Combined (n = 95) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women, % (n) | 63% (36) | 47% (18) | 57% (54) |

| Education years, mean (SD) | 4.6 (5.2) | 5.7 (5.3) | 5.01 (5.2) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 73.8 (7.1) | 74.9 (7.7) | 74.2 (7.3) |

| 3MSE score, mean (SD) | 72 (12.1) | 56.0 (24.4) | 65.5 (19.7) |

| Stroke, % (n) | 12.3% (7) | 34.2 (13) | 21% (20) |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 40.4% (23) | 40.0% (15) | 40% (38) |

| Functional impairment, mean (SD) | 3.4 (2.9) | 7.0 (2.9) | 4.8 (3.4) |

| NPI score, mean, (SD) | 3.7 (6.6) | 13.9 (16.6) | 7.8 (12.7) |

Bivariate analysis

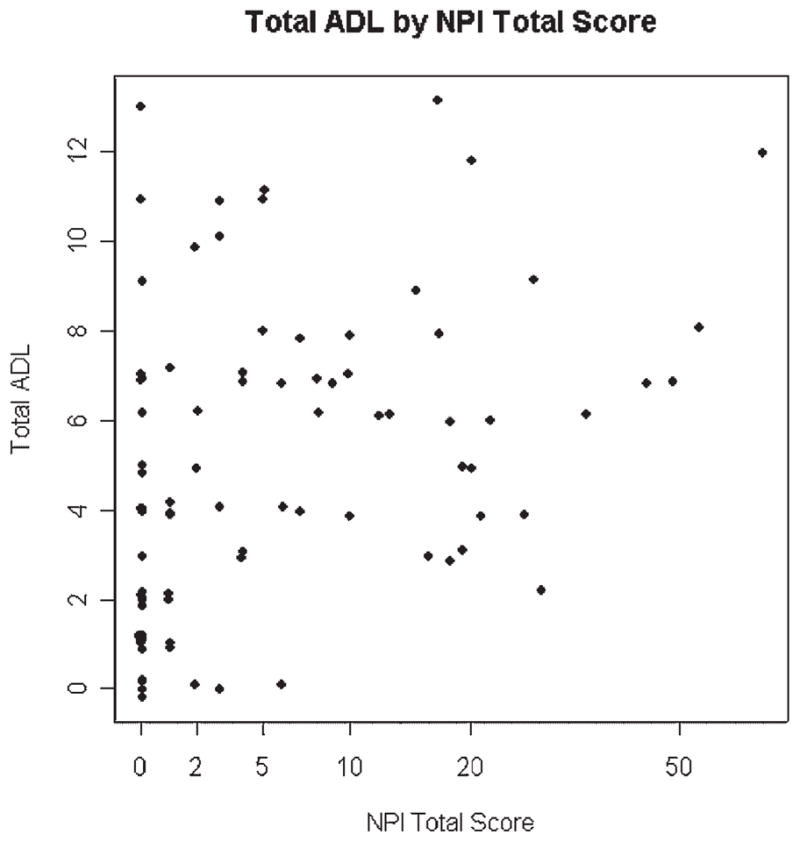

The association of variables with ADL impairment is shown in Table 2. In addition to NPI total score or depression score, greater cognitive impairment, older age, and history of stroke were associated with greater functional impairment. Results are generally consistent across the CIND and dementia groups. A scatter plot of total ADL score by NPI score may be seen in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Correlates of functional impairment in cognitively impaired not demented, demented, and combined sample

| Subject characteristics | CIND (n = 57) | Dementia (n = 38) | Combined (n = 95) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous/ordinal variables | Spearman rho (p) | Spearman rho (p) | Spearman rho (p) |

| Education years | −0.06 (0.68) | −0.21 (0.21) | −0.02 (0.86) |

| Age | 0.27 (0.04) | 0.28 (0.09) | 0.24 (0.02) |

| 3MSE score | −0.14 (0.30) | −0.28 (0.09) | −0.32 (0.002) |

| NPI total score | 0.38 (0.004) | 0.27 (0.10) | 0.47 (0.0001) |

| NPI depression score | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.28 (0.09) | 0.32 (0.002) |

| Dichotomous variables | Ranksum (p) | Ranksum (p) | Ranksum z (p) |

| Stroke | −1.68 (0.09) | −0.37 (0.71) | −2.65 (0.008) |

| Diabetes, % (n) | −0.63 (0.53) | −0.48 (0.63) | −0.85 (0.85) |

| Female, % (n) | 0.0 (1.0) | −1.3 (0.20) | 0.193 (0.85) |

Figure 1.

Functional impairment score by Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) total score. NPI total score is log transformed (points on plot have been jittered––moved an insignificant amount) to make identical values visible.

Because the NPI is a summary measure that includes ten different symptoms, the relationship of individual neuropsychiatric symptoms with disability was examined for the entire sample and separately for the CIND and dementia groups (Table 3). With two exceptions (disinhibition and aberrant motor activity), individual neuropsychiatric symptoms are significantly associated (p <0.05) with disability in the overall group with consistent patterns for both the CIND and dementia groups (though not always reaching statistical significance).

Table 3.

Association of Neuropsychiatric Inventory subscale symptom scores with functional impairment in cognitively impaired not demented, demented, and combined sample

| Individual NPI symptoms | CIND (n =57) | Dementia (n =38) | Combined (n =95) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spearman rho (p) | Spearman rho (p) | Spearman rho (p) | |

| Depression | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.28 (0.09) | 0.47 (0.0001) |

| Anxiety | 0.36 (0.007) | 0.29 (0.08) | 0.35 (0.0005) |

| Elation | 0.17 (0.20) | 0.11 (0.49) | 0.26 (0.01) |

| Apathy | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.19 (0.25) | 0.24 (0.02) |

| Disinhibition | 0.23 (0.08) | −0.19 (0.24) | 0.15 (0.14) |

| Irritability | 0.17 (0.20) | 0.16 (0.33) | 0.28 (0.007) |

| Aberrant Motor | 0.22 (0.10) | −0.01 (0.98) | 0.16 (0.12) |

| Delusions | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.24 (0.16) | 0.35 (0.0006) |

| Hallucinations | 0.13 (0.33) | 0.36 (0.03) | 0.37 (0.0002) |

| Agitation | 0.27 (0.04) | 0.21 (0.21) | 0.35 (0.0006) |

| NPI total | 0.38 (0.004) | 0.27 (0.10) | 0.47 (0.0001) |

Multivariate analysis

Multivariate analyses results are presented in Tables 4 and 5. The results are consistent when either the NPI total score (Table 4) or NPI depression subscale score (Table 5) was included in the model, although the statistical significance of the NPI depression subscale was less than for the full scale (p =0.04). Alternate multiple regression models were fit with variables transformed to achieve approximately normal distributions, and results were similar.

Table 4.

Final multivariate regression of Neuropsychiatric Inventory total score on functional impairment score

| Beta | SE | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total NPI | 0.078 | 0.025 | 3.16 | 0.002 |

| Total 3MS | −0.042 | 0.016 | −2.6 | 0.011 |

| Age | 0.1335 | 0.040 | 3.31 | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.98 | 0.7115 | 2.78 | 0.007 |

| Constant | −3.7 | 3.6 | −1 | 0.3 |

Table 5.

Final multivariate regression of Neuropsychiatric Inventory depression subscale score on functional impairment score

| Beta | SE | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPI depression | 0.241 | 0.111 | 2.2 | 0.034 |

| Total 3MS | −0.042 | 0.016 | −2.6 | 0.011 |

| Age | 0.131 | 0.042 | −3.0 | 0.003 |

| Stroke | 2.134 | 0.734 | 2.9 | 0.015 |

| Constant | −2.52 | 3.53 | −0.72 | 0.476 |

Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted examining the relationship of NPI total score to disability separately for the dementia and CIND groups. In the unadjusted models, the direction and size of the coefficients was similar for the two groups and consistent with results for the entire sample. However, the association of NPI total score with disability did not reach statistical significance (i.e. 10 <p <0.20) likely due to reduced sample size.

DISCUSSION

We found overall neuropsychiatric symptom score to be significantly associated with disability among older, cognitively impaired, Latinos. This effect was present even after accounting for the effects of other potentially confounding variables, including socio-demographic characteristics, co-morbid medical illness, and level of cognitive impairment. In addition, our results indicate the neuropsychiatric symptoms have a similar effect on disability among those who are cognitively impaired but not demented and those who are demented. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms on cognitively impaired Latino elderly and therefore extends similar previous findings in largely Caucasian samples.

There are several potential reasons why neuropsychiatric symptoms may influence everyday function and lead to increased disability. For example, depression along with other neuropsychiatric symptoms such as apathy are associated with a lack of energy and interest that may lead to decreased motivation to engage in or follow-through completely with various instrumental ADLs (Raji et al., 2002). Other symptoms, such as irritability, agitation, or psychosis, may lead to resistance to care that may be interpreted by caregivers as functional impairment.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, our study is based on an epidemiological sample that was assessed through a muti-stage process that relied heavily up on cognitive screening instruments and a neuropsychological battery. While our approach is consistent with other large epidemiological studies (e.g. Cache County or Cardiovascular Health Study), it is possible that some persons meeting criteria for dementia may have been missed and misclassified as being cognitively impaired not demented. However, there is evidence that this type of error is not substantial, including the significant lower rates of almost all types of neuopsychiatric symptoms in the CIND group compared with the dementia group (Hinton et al., 2003). A second limitation of this study is the modest size of the sample which made it difficult to conduct subgroup analyses due to reduced power.

This study has potentially important public health implications, particularly with respect to disparities and health. Prior research suggests that Latinos with dementia and milder forms of cognitive impairment suffer from higher levels of neuropsychiatric symptoms compared with white non-Hispanics (Sink et al., 2004). This study adds to our prior work and highlights the adverse consequences of higher neuropsychiatric symptom burden in cognitively impaired Latinos. The significant association of neuropsychiatric symptoms with disability underscores their clinical importance and supports the validity of the specific measure used in this study (i.e. the Neuropsychiatric Inventory) among Latinos. It should be emphasized that the most common neurospychiatric symptom in both the dementia and the CIND group was depression, a clinical condition for which we have effective interventions (Hinton and Arean, in press), including for those with dementia (Lyketsos et al., 2003). Also, among older adults, clinical depression may also underpin other neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as irritability and aggression. In prior studies, we found a strong association of neuropsychiatric symptoms with caregiver depression and considerable gaps in formal care as perceived by Latino families caring for someone with dementia (Hinton et al., 2003; Hinton et al., 2006). Future studies are needed to examine creative ways of providing more timely and effective care to Latino elderly suffering from neuropsychiatric symptoms, particularly in primary care settings where the vast majority of elderly with dementia are seen.

KEY POINTS

Overall neuropsychiatric symptom burden is significantly associated with disability in cognitively impaired Latino elderly

Depression is also significantly associated with disability in persons who are cognitively impaired but not demented and those with dementia

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grants K2319809, R01AG12975, and P30AG010129 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

References

- Boyle PA, Malloy PF, Salloway S, et al. Executive dysfunction and apathy predict functional impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:214–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ronchi D, Bellini F, Berardi D, et al. Cognitive status, depressive symptoms, and health status as predictors of functional disability among elderly persons with low-to-moderate education: the Faenza Community Aging Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:672–685. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espiritu DA, Rashid H, Mast BT, et al. Depression, cognitive impairment and function in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1098–1103. doi: 10.1002/gps.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PH, McDonald MV. Conducting translation research in the home care setting: lessons from a Just-in-Time Reminder Study. Worldviews Eviden Based Nurs. 2004;1:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2004.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-Mental State’: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatric Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB, Rozzini L, Gozzetti A, et al. Behavioral symdromes in Alzheimer’s disease: description and correlates. Dement Geriatr Cog Disord. 1999;10:130–138. doi: 10.1159/000017113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geda YE, Smith GE, Knopman DS, RC, et al. De novo genesis of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) Int Psychogeriatr. 2004;16:51–60. doi: 10.1017/s1041610204000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haan MN, Mungas DM, Gonzalez HM, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older latinos: the influence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, stroke and genetic factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:169–177. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Chambers D, Velasquez A, et al. Dementia neuropsychiatric symptom severity, help-seeking patterns, and family caregiver unmet needs in the Sacramento area Latino study on aging (SALSA) Clin Gerontologist. 2006;29:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Haan M, Geller S, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Latino elderly with dementia and mild cognitive impairment without dementia and factors that modify their impact on caregivers. Gerontologist. 2003;43:669–677. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Areán P. Epidemiology, assessment and treatment of depression in older Latinos. In: Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Gullotta TP, editors. Depression in Latinos: Epidemiology, Treatment, and Prevention. Springer; New York: NY: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A. A short form of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychologic Med. 1994;24:145–153. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002691x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford A, Moskowitz R, Jackson B, Jaffe M. Studies of illness in the aged: the index of ADL, a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. J Am Medic Assoc. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Schulz R, Martire LM, et al. The course of functional decline in older people with persistently elevated depressive symptoms: longitudinal findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatric Society. 2005;53:569–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, et al. Prevalance of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. J Am Medic Assoc. 2002;288:1475–1843. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, et al. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):737–746. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mega M, Cummings J, Fiorello T, Gorbein J. The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996;46:130–135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE. Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. J Am Geriatr Society. 2002;50:1045–4050. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50259.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungas D, Reed BR, Marshall SC, Gonzalez HM. Development of psychometrically matched English and Spanish language neuropsychological tests for older persons. Neuropsychology. 2000;14:209–223. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton LE, Malloy PF, Salloway S. The impact of behavioral symptoms on activities of daily living in patients with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz F, Fitten LJ, Cummings JL, et al. Neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms in a community sample of Hispanics with Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Alzheim Dis Other Dement. 2006;21:263–273. doi: 10.1177/1533317506289350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raji MA, Ostir GV, Markides KS, Goodwin JS. The interaction of cognitive and emotional status on subsequent physical functioning in older Mexican Americans: findings from the Hispanic established population for the epidemiologic study of the elderly. J Gerontology Series A: Biologic Sci Medic Sci. 2002;57:M678–M682. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.10.m678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein AH. Outcome assessment: aggregate outcome management across the continuum of care. Ambulatory Outreach. 1998:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Yaffe K. Ethnic differences in the prevalence and pattern of dementia-related behaviors. J Am Geriatr Society. 2004;52:1277–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Does co-morbid depressive illness magnify the impact of chronic physical illness? A population-based perspective. Psychologic Mede. 2006;36:587–596. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran M, Bedard M, Molloy DW, JA, et al. Associations between Psychotic symptoms and dependence in activities of daily living among older adults with Alzheimer’s Disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003;15:171–179. doi: 10.1017/s1041610203008858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gool CH, Kempen GI, Penninx BWJH, et al. Impact of depression on disablement in late middle aged and older persons: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilalta-Franch J, Lozano-Gallego M, Hernandez-Ferrandiz M, et al. The neuropsychiatric inventory: Psychometric properties of its adaptation into Spanish. Revista de Neurologica. 1999;29:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]