Abstract

We describe a patient with multiple congenital anomalies including deafness, lacrimal duct stenosis, strabismus, bilateral cervical sinuses, congenital cardiac defects, hypoplasia of the corpus callosum, and hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis. Mutation analysis of EYA1, SIX1, and SIX5, genes that underlie otofaciocervical and/or branchio-oto-renal syndrome, was negative. Pathologic diagnosis of the excised cervical sinus tracts was revised on re-examination to heterotopic salivary gland tissue. Using high resolution chromosomal microarray analysis, we identified a novel 2.52 Mb deletion at 19p13.12, which was confirmed by fluorescent in-situ hybridization and demonstrated to be a de novo mutation by testing of the parents. Overall, deletions of chromosome 19p13 are rare.

Keywords: craniofacial, 19p13, Chromosomal Microarray Analysis

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of communicatively significant hearing loss is approximately 2–4 in 1000 births [Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2000]. Data from infants with identified risk indicators for hearing impairment has suggested that 70% of hearing loss is nonsyndromic and 30% is syndromic [Bergstrom et al., 1971]. Both nonsyndromic and syndromic deafness are remarkably genetically heterogeneous [Brown et al., 2008]; even the most common syndromes associated with sensorineural hearing loss such as Waardenburg syndrome comprise <3% of congenital deafness cases [Morell et al., 1997]. Deafness may also be associated with contiguous gene deletion syndromes [Bitner-Glindzicz, 2002; Rickard et al., 2001]. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) has allowed identification of the molecular genetic etiology in children with multiple congenital anomalies without unifying clinical diagnoses. We report on a child with multiple congenital anomalies who was found to have a deletion of chromosome 19p13.12 by CMA, confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH).

CLINICAL REPORT

Patient

The patient is a 10-year-old girl born at term following pregnancy complicated by reduced amniotic fluid. She was delivered by emergent cesarean for decreased fetal movement, with Apgar scores of 3 and 9 at one and five minutes, respectively. Her birth weight was 2.13 kg, below the first centile. She required supplemental oxygen for the first few days of life.

Craniofacial anomalies noted at ages 6 months - 9 years (Fig 1A–D) include malar hypoplasia, tall forehead, marked occipital flattening, telecanthus, ptosis, down-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, glabellar hemangioma, short nose with anteverted nares, long philtrum, flattened vermillion border, and mild micrognathia. The soft and hard palates had no clefting. She also has small, rounded, mildly low set auricles with pitting of the lobule bilaterally and mild stenosis of the external auditory canals.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of the subject taken at age 6 months (A), 2 years (B), 6 years (C) and 9 years (D) of age demonstrate tall forehead, telecanthus, ptosis, downsloping palpebral fissures, short nose with anteverted nares, long philtrum, and flattened vermillion border.

The patient has a congenital right profound sensorineural hearing loss and a left mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss. She underwent tympanostomy tube placement on two occasions for treatment of Eustachian tube dysfunction. She had an additional variable conductive component to her left hearing loss depending on the status of her middle ear. Temporal bone computed tomography scan at 6 years of age (Fig 2A–B) showed mild dysplasia of the semicircular canals, with a blunted and bulbous lateral semicircular canal on the right. She currently wears an over-the-ear hearing aid in the left ear, and is a candidate for a bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA) in the future.

Fig. 2.

Temporal bone computed tomography scan obtained at age 6 years. 2A. Axial sections through the lateral semicircular canals (LSCC) show asymmetry of the LSCC (arrows), with the right LSCC more bulbous and blunt than the left. 2B. Asymmetry is more obvious on coronal sections through the LSCC (arrows).

Ocular anomalies included bilateral strabismus (for which she underwent bilateral inferior oblique myotomies), cupping of the optic discs bilaterally, and nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Oral anomalies noted subsequently included hypodontia (small, widely spaced teeth, with 4 missing teeth), and enamel defects of the molars.

The patient had several congenital cardiac anomalies, including small secundum atrial septal defect, small ventricular septal defect, and patent ductus arteriosus, all of which closed spontaneously by age 3 months. She also had supernumerary abdominal nipples bilaterally. Examination of the hands showed brachydactyly and terminal abbreviation of the digits with hypoplastic nails, particularly evident on the thumbs (Fig 3). Radiographs of the hands demonstrated reduction in size of all the distal phalanges (Fig 4).

Fig. 3.

Photographs of the dorsal (A) and ventral (B) surfaces of the hands illustrate brachydactyly and terminal abbreviation of the digits with hypoplastic nails, particularly evident on the thumbs.

Fig. 4.

Radiographs of the hands demonstrate reduction in size of all the distal phalanges.

She had bilateral cervical sinuses which were excised at age 6 due to chronic drainage. The left sinus tract was approximately 1.5 cm in length and appeared to terminate in the region of the thoracic duct, near the base of the internal jugular vein, in a course atypical of branchial cleft sinus tracts. The right cervical anomaly was little more than a skin dimple, and was excised with a small cuff of subcutaneous tissue. While the initial pathological interpretation was nonspecific, re-examination was consistent with heterotopic salivary gland tissue.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain during infancy demonstrated minor hypoplasia of the corpus callosum and cerebellar vermis, prominence of the cisterna magna and fourth ventricle, but normal sized lateral and third ventricles and no evidence of Dandy-Walker or Chiari malformation. She was also found to be developmentally delayed. IQ testing performed at age 5 showed a verbal IQ of 69, and full scale IQ of 63. At age 9 she was able to count to 10.

Onset of menarche occurred at age 9 years. She experienced heavy menstrual bleeding with one episode at age 10 years requiring transfusion for symptomatic anemia. Platelet aggregation and secretion studies demonstrated abnormal platelet secretion responses to all agonists, consistent with a storage pool disorder. Hematologic evaluation was otherwise negative, and no bleeding tendency had been noted at the time of surgical procedures.

Medical genetic evaluation included a normal karyotype, fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) 22q11 analysis, renal ultrasound, and skeletal survey. Both parents as well as an older brother are asymptomatic.

METHODS

DNA samples

The proposita and her parents were referred to the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) cytogenetics laboratory for clinical array-comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analysis. DNA samples were obtained with informed consents approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Subject Research at BCM. DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Puregene DNA extraction kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Array –based comparative genomic hybridization

The chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) is a clinically-available microarray containing 853 BAC and PAC clones designed to cover genomic regions of 75 known genomic disorders, all 41 subtelomeric regions, and 43 pericentromeric regions [Cheung et al., 2005]; Chromosome Microarray Analysis, V.5, http://www.bcm.edu/geneticlabs/cma/tables.html). For each sample, two experiments were performed with reversal of the dye labels for the control and test samples, and the data from both dye-reversed hybridizations were integrated to determine inferences for each case. The fluorescent signals on the slides were scanned into image files using an Axon microarray scanner and ScanArray software (GenePix 4000B from Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The quantization data were subjected to normalization as described [Lu et al., 2007].

Fluorescent in-situ hybridization (FISH) analysis

FISH was performed on PHA-stimulated peripheral blood lymphocytes obtained from the proband and her parents using a standard protocol. FISH analysis used the clone RP11-56K21 to confirm the deletion observed by CMA.

Whole genome array analysis on the proposita and both parents

The whole Genome Oligo Microarray Kits 244K (Agilent Technologies, Inc, CA, USA) were used in both of the parents and proposita respectively, to further refine the identified genomic gains and losses. The procedures for DNA digestion, labeling, and hybridization were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions with some modifications [Probst et al., 2007].

Mutation screening of BOR genes

All exons and flanking intronic sequences of EYA1, SIX1, and SIX5 were sequenced as previously described [Hoskins et al., 2007; Ruf et al., 2004].

RESULTS

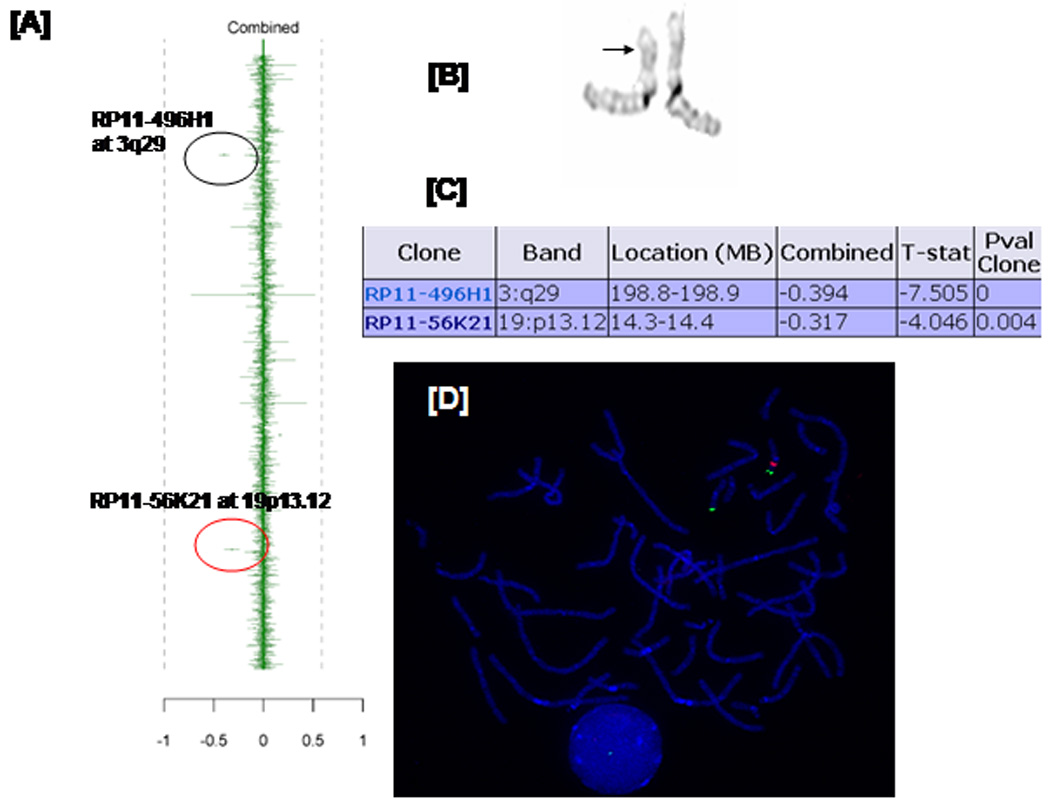

CMA revealed a loss in copy number in the proximal region of the short arm of chromosome 19 (19p13.12), detected with one clone (RP11-56K21) as indicated in the red circle. (Fig 5A). There is also a loss in copy number in the distal long arm of chromosome 3 at band 3q29 detected with one clone (RP11- 496H1) as indicated by the black circle. This loss is considered a common polymorphism in the Baylor and Toronto data bases. Karyotype of G-banded chromosomes revealed an apparent cryptic deletion on the short arm of one chromosome 19 between bands p13.11 and p13.13 as indicated by the arrow (Fig 5B). The combined log ratio of −0.317 is significant by T statistics (p value = 0.004), as shown in Figure 5C, indicating a loss in copy number in this region. The deletion was further confirmed by FISH analysis (Figure 5D) and is considered de novo, as FISH analysis with the above clone showed no evidence of a deletion in either parent.

Fig. 5.

Chromosome microarray data demonstrating 19p13.1 deletion. [A] Graphic representation. Each dot with vertical line deviating from the mean represents a value corresponding to loss or gain in copy number. In the combined column, data are average with gains to the right and losses to the left. Red circle indicates strong indication of a loss of the clone corresponding to the 19p13.1 region while the black circle indicates a loss of the clone corresponding to 3q29. The latter represents a commonly seen polymorphism. [B] Partial karyotype for chromosome 19 showing subtle differences on the short arm of chromosome 19 as indicated by the arrow. [C] The combined log ratio of −0.317 is significant by T statistics with p value at 0.004 suggesting a deletion in this region.

[D] FISH confirmation. Only one red signal is demonstrated for BAC clone RP11-56K21, confirming haploinsufficiency shown by CMA, while the subtelomeric probe (129F16/SP6) located on the distal short arm of chromosome 19 showed a normal hybridization pattern (two green signals).

In order to more precisely characterize the deletion, the use of the whole genome 244 K array (Agilent Techologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) revealed a 2.52 Mb deletion on the short arm of chromosome 19 at band p13.12, from 13.93 Mb to 16.36 Mb (Fig 6A). Neither parent carries the deletion (Fig 6B). A list of genes mapping to this interval is presented in Table I.

Fig. 6.

The loss on the chromosome 19 at band p13.12 is displayed from Test/Reference ratio data of this patient in a 244K microarray from Agilent. The Agilent aberration detection algorithm detects intervals of consistent high or low log ratios within an ordered set of probes by measuring a set of genomic locations and considering their genomic order to make amplification or deletion calls. [A] ~2.52 mega base loss at 19p13.12 is observed. [B] High-resolution view of the deleted region of the patient as compared to her normal parents indicating this is a de novo event.

Table 1.

Genes contained in 2.52 Mb deleted interval.

| Gene | Description |

|---|---|

| ABHD9 | Abhydrolase domain-containing protein 9 precursor |

| AKAP8 | A-kinase anchor protein 8 |

| AKAP8L | A-kinase protein 8-like |

| AP1M1 | Medium chain clathrin-associated protein complex Ap1 |

| ASF1B | Anti-silencing function 1B |

| BRD4 | Bromodomain –containing protein 4 |

| CASP14 | Caspase 14 precursor |

| CC2D1A | Coiled-coil and C2 domains-containing protein 1A |

| CCDC105 | Coiled-coil domain containing 105 |

| CIB3 | Similar to DNA-dependent protein-kinase catalytic subunit- interacting protein 2 |

| CD97 | CD97 antigen isoform 1 precursor |

| CYP4F8 | Cytochrome P450 family 4 (also CYP4F3, CYP4F2, CYP4F11) |

| DDX39 | Dead Box protein 39 |

| DNAJB1 | DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 1 |

| EMR2 | Egf-like module-containing mucin like receptor 2 |

| EMR3 | Egf-like module containing mucin-like receptor 3 |

| EPS15L1 | Epidermal growth factor receptor substrate 15-like 1 |

| GIPC1 | PDZ domain-containing protein GIPC1 |

| GPSN2 | Synaptic glycoprotein SC2 |

| HSH2D | Hematopoeitic SH2 domain containing |

| IL27RA | Interleukin-27 receptor subunit alpha precursor |

| ILVBL | Similar to thiamine pyrophosphate binding proteins |

| KIN27 | Protein kinase A-Alpha |

| KLF2 | Krueppel-like factor 2 |

| LPHN1 | Latrophilin 1 isoform 1 precursor |

| NDUFB7 | NADH dehydrogenase 1 beta subcomplex subunit 7 |

| NOTCH3 | Homologue of Drosophila Notch |

| PODNL1 | Podocan-like 1 |

| OR1/1, | Olfactory receptors (also OR10H2, OR10H4, OR10H5, OR10H1) |

| OR7A10 | Olfactory receptor, family 7, subfamily A (also OR7A17, OR7A5) |

| OR7C1 | Olfactory receptor, family 7, subfamily C (also OR7C2) |

| PGLYRP2 | Peptidoglycan recognition protein L precursor |

| PKN1 | Protein kinase N1 |

| PTGER1 | Prostaglandin E receptor 1, subtype EP1 |

| PRKACA | cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit |

| RLN3 | Relaxin 3 preprotein |

| RFX1 | MHC class II regulatory factor |

| SAMD1 | Sterile alpha motif domain containing 1 |

| SC2 | Synaptic glycoprotein SC2 |

| SLC1A6 | Solute carrier family 1 |

| SYDE1 | Synapse defective 1 |

| TPM4 | Tropomyosin alpha-4 chain |

| ZNF333 | Zinc finger protein 333 |

DISCUSSION

Isolated deletions of chromosome 19p13 are rare. Subtelomeric FISH analysis identified a deletion of 19p13.3-pter in a patient with cleft palate, hearing impairment, congenital heart malformation, keloid scarring, immunodeficiency, seizures, umbilical hernia, and learning disability [Archer et al., 2005]. Facial dysmorphisms included thick eyebrows, long face with hypoplastic maxillae, narrow nose with a short philtrum, thin upper lip and full lower lip, large low-set ears, and occipital patchy alopecia. Like our patient, hearing loss was mixed (sensorineural and conductive), and bilateral hearing aids were required. A patient with a 19p deletion identified by karyotype analysis was reported with dysmorphic facies, deafness and umbilical hernia [Hurgoiu and Suciu, 1984].

Several nonsyndromic deafness loci overlap with the deletion found in our patient. In a consanguineous family with prelingual severe-to-profound deafness, linkage analysis identified two regions of significant linkage, a 32 cM region on 19p13.3-p13.1 and a 39 cM region on 3q21.3-q25.2, both with LOD scores of 2.78 [Chen et al., 1997]. This family was assigned the locus name DFNB15, and a family with dominant low to mid frequency sensorineural hearing loss was found to map to an overlapping locus, DFNA57 [Bonsch et al., 2008]. Neither the DFNB15 nor DFNA57 genes have yet been identified. GTPBP3, mitochondrial GTP binding protein 3, is a putative modifier for mitochondrial deafness and maps to the deleted region [Bykhovskaya et al., 2004]. Two additional loci for autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness, DFNB68 and DFNB72, have been mapped to chromosome 19p13 [Ain et al., 2007; Santos et al., 2006]. However, both of these loci are telomeric to our patient’s deletion.

Branchio-oculo-facial (BOF) syndrome is a very rare disorder characterized by the presence of variable craniofacial, ocular, cervical, auricular, dental, renal, and sometimes neurodevelopmental anomalies. These anomalies may include cervical and/or pre-auricular branchial cleft sinuses or skin lesions, low-set, posteriorly rotated, malformed auricles, conductive and/or sensorineural hearing loss, upper lip and palate malformations ranging from pseudocleft to complete cleft of lip and palate, ocular abnormalities including nasolacrimal duct obstruction and coloboma of the iris, oligodontia, and often some degree of developmental delay [Fujimoto et al., 1987; Lin et al., 1995]. While our patient shared some of these features, she has a normal palate and does not have the typical facial features of BOF; nor are cardiac malformations typical of BOF. The gene underlying BOF syndrome has recently been identified as TFAP2A, transcription factor AP-2 alpha [Milunsky et al., 2008].

Branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome (OMIM: 113650) and branchio-otic (BOS) syndrome (OMIM: 608389) are characterized by hearing loss, lacrimal duct stenosis, and branchial cleft fistulas, with or without renal anomalies. We analyzed the three known genes for BOR/BOS (EYA1, SIX5, and SIX1) without identifying mutations, and the patient’s deletion does not involve any known BOR genes or loci. In addition, the cervical sinuses were diagnosed as heterotopic salivary gland tissue on pathologic re-examination, and the tracts did not follow a typical course of branchial cleft anomalies.

Otofaciocervical [OFC] syndrome [OMIM 166780] represents another potentially related syndrome, as it is characterized by similar facial features, branchial cleft fistulas, mild developmental delay, sensorineural hearing loss, and congenital heart defects. Two patients with OFC syndrome have been reported to have deletions involving EYA1 [Estefania et al., 2006; Rickard et al., 2000].

Precisely defining the microdeletion boundaries provides positional candidate genes which can be assayed for point mutations in other patients with similar phenotypes, as has been shown for CHARGE [Vissers et al., 2004] and Usher syndromes [Bitner-Glindzicz 2002]. By describing the phenotype of a patient with an unusual deletion of chromosome 19p13, we hope that diagnosis and prognosis will improve for additional patients with this constellation of clinical findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the family for their cooperation and participation, and Laura Miller for assistance in preparing the manuscript. F.H. is supported by NIH grant 1R01-HD45345.

REFERENCES

- Ain Q, Nazli S, Riazuddin S, Jaleel AU, Riazuddin SA, Zafar AU, Khan SN, Husnain T, Griffith AJ, Ahmed ZM, Friedman TB. The autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness locus DFNB72 is located on chromosome 19p13.3. Hum Genet. 2007;122:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0418-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer HL, Gupta S, Enoch S, Thompson P, Rowbottom A, Chua I, Warren S, Johnson D, Ledbetter DH, Lese-Martin C, Williams P, Pilz DT. Distinct phenotype associated with a cryptic subtelomeric deletion of 19p13.3-pter. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2005;136A:38–44. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom L, Hemenway WG, Downs MP. A high risk registry to find congenital deafness. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1971;4:369–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner-Glindzicz M. Hereditary deafness and phenotyping in humans. Br Med Bull. 2002;63:73–94. doi: 10.1093/bmb/63.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsch D, Schmidt CM, Scheer P, Bohlender J, Neumann C, am Zehnhoff-Dinnesen A, Deufel T. [A new locus for an autosomal dominant, non-syndromic hearing impairment (DFNA57) located on chromosome 19p13.2 and overlapping with DFNB15] HNO. 2008;56:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s00106-007-1633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Hardisty-Hughes RE, Mburu P. Quiet as a mouse: dissecting the molecular and genetic basis of hearing. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:277–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykhovskaya Y, Mengesha E, Wang D, Yang H, Estivill X, Shohat M, Fischel-Ghodsian N. Phenotype of non-syndromic deafness associated with the mitochondrial A1555G mutation is modulated by mitochondrial RNA modifying enzymes MTO1 and GTPBP3. Mol Genet Metab. 2004;83:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Wayne S, Bell A, Ramesh A, Srisailapathy CR, Scott DA, Sheffield VC, Van Hauwe P, Zbar RI, Ashley J, Lovett M, Van Camp G, Smith RJ. New gene for autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss maps to either chromosome 3q or 19p. Am J Med Genet. 1997;71:467–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung SW, Shaw CA, Yu W, Li J, Ou Z, Patel A, Yatsenko SA, Cooper ML, Furman P, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR, Chinault AC, Beaudet AL. Development and validation of a CGH microarray for clinical cytogenetic diagnosis. Genet Med. 2005;7:422–432. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000170992.63691.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estefania E, Ramirez-Camacho R, Gomar M, Trinidad A, Arellano B, Garcia-Berrocal JR, Verdaguer JM, Vilches C. Point mutation of an EYA1-gene splice site in a patient with oto-facio-cervical syndrome. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70:140–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto A, Lipson M, Lacro RV, Shinno NW, Boelter WD, Jones KL, Wilson MG. New autosomal dominant branchio-oculo-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1987;27:943–951. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320270422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins BE, Cramer CH, Silvius D, Zou D, Raymond RM, Orten DJ, Kimberling WJ, Smith RJ, Weil D, Petit C, Otto EA, Xu PX, Hildebrandt F. Transcription factor SIX5 is mutated in patients with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:800–804. doi: 10.1086/513322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurgoiu V, Suciu S. Occurrence of 19p- in an infant with multiple dysmorphic features. Ann Genet. 1984;27:56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Pediatrics. 2000;106:798–817. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AE, Gorlin RJ, Lurie IW, Brunner HG, van der Burgt I, Naumchik IV, Rumyantseva NV, Stengel-Rutkowski S, Rosenbaum K, Meinecke P, Muller D. Further delineation of the branchio-oculo-facial syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1995;56:42–59. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320560112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Shaw CA, Patel A, Li J, Cooper ML, Wells WR, Sullivan CM, Sahoo T, Yatsenko SA, Bacino CA, Stankiewicz P, Ou Z, Chinault AC, Beaudet AL, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Ward PA. Clinical implementation of chromosomal microarray analysis: summary of 2513 postnatal cases. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milunsky JM, Maher TA, Zhao G, Roberts AE, Stalker HJ, Zori RT, Burch MN, Clemens M, Mulliken JB, Smith R, Lin AE. TFAP2A mutations result in branchio-oculo-facial syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1171–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell R, Friedman TB, Asher JH, Jr, Robbins LG. The incidence of deafness is nonrandomly distributed among families segregating for Waardenburg syndrome type 1 (WS1) J Med Genet. 1997;34:447–452. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.6.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst FJ, Roeder ER, Enciso VB, Ou Z, Cooper ML, Eng P, Li J, Gu Y, Stratton RF, Chinault AC, Shaw CA, Sutton VR, Cheung SW, Nelson DL. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) detects a large X chromosome deletion including FMR1, FMR2, and IDS in a female patient with mental retardation. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:1358–1365. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard S, Boxer M, Trompeter R, Bitner-Glindzicz M. Importance of clinical evaluation and molecular testing in the branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome and overlapping phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2000;37:623–627. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.8.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard S, Parker M, van't Hoff W, Barnicoat A, Russell-Eggitt I, Winter RM, Bitner-Glindzicz M. Oto-facio-cervical (OFC) syndrome is a contiguous gene deletion syndrome involving EYA1: molecular analysis confirms allelism with BOR syndrome and further narrows the Duane syndrome critical region to 1 cM. Hum Genet. 2001;108:398–403. doi: 10.1007/s004390100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf RG, Xu PX, Silvius D, Otto EA, Beekmann F, Muerb UT, Kumar S, Neuhaus TJ, Kemper MJ, Raymond RM, Jr, Brophy PD, Berkman J, Gattas M, Hyland V, Ruf EM, Schwartz C, Chang EH, Smith RJ, Stratakis CA, Weil D, Petit C, Hildebrandt F. SIX1 mutations cause branchio-oto-renal syndrome by disruption of EYA1-SIX1-DNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8090–8095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308475101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos RL, Hassan MJ, Sikandar S, Lee K, Ali G, Martin PE, Jr, Wambangco MA, Ahmad W, Leal SM. DFNB68, a novel autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment locus at chromosomal region 19p13.2. Hum Genet. 2006;120:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers LE, van Ravenswaaij CM, Admiraal R, Hurst JA, de Vries BB, Janssen IM, van der Vliet WA, Huys EH, de Jong PJ, Hamel BC, Schoenmakers EF, Brunner HG, Veltman JA, van Kessel AG. Mutations in a new member of the chromodomain gene family cause CHARGE syndrome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:955–957. doi: 10.1038/ng1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]