Abstract

ING proteins have been proposed to alter chromatin structure and gene transcription to regulate numerous aspects of cell physiology, including cell growth, senescence, stress response, apoptosis, and transformation. ING1, the founding member of the inhibitor of growth family, encodes p37Ing1, a plant homeodomain (PHD) protein that interacts with the p53 tumor suppressor protein and seems to be a critical cofactor in p53-mediated regulation of cell growth and apoptosis. In this study, we have generated and analyzed p37Ing1-deficient mice and primary cells to further explore the role of Ing1 in the regulation of cell growth and p53 activity. The results show that endogenous levels of p37Ing1 inhibit the proliferation of p53-wild-type and p53-deficient fibroblasts, and that p53 functions are unperturbed in p37Ing1-deficient cells. In addition, loss of p37Ing1 induces Bax expression and increases DNA damage–induced apoptosis in primary cells and mice irrespective of p53 status. Finally, p37Ing1 suppresses the formation of spontaneous follicular B-cell lymphomas in mice. These results indicate that p53 does not require p37Ing1 to negatively regulate cell growth and offers genetic proof that Ing1 suppresses cell growth and tumorigenesis. Furthermore, these data reveal that p37Ing1 can negatively regulate cell growth and apoptosis in a p53-independent manner.

Introduction

ING1 was initially isolated in a screen to identify genes that were underexpressed in transformed versus normal human epithelium (1). Subsequently, ING1 was identified as a member of a five-gene ING family that encode plant homeodomain (PHD)-finger domain proteins conserved in yeast and vertebrates (2). Forced overexpression of ING1 in normal human diploid fibroblast cells was found to inhibit cell growth by inducing a G1-phase cell cycle arrest. Conversely, down-regulation of ING1 in cell lines by antisense RNA increased cell proliferation and cell transformation, as assayed by colony formation in soft agar (1, 3), and inhibited Myc-induced apoptosis (4). The ability of ING1 to inhibit cell growth and promote apoptosis in these various assays indicated that ING1 might function as a tumor suppressor.

The murine Ing1 gene produces several spliced isoforms of Ing1 mRNA that generate two distinct Ing1 proteins (5). The larger 37-kDa protein (p37Ing1) contains all of the residues present in the smaller 31-kDa (p31Ing1) protein, as well as additional sequences at the NH2 terminus that interact with the p53 tumor suppressor protein (5). Both mouse p37Ing1 and the human orthologue p33 ING1 have been shown to coimmunoprecipitate with p53 in transfected cells (5, 6). Furthermore, p33 ING1 has been reported to stabilize p53 levels in transfected cells by binding with p53 and blocking murine double minute-2 (Mdm2)-p53 interactions and by inhibiting hSir2 deacetylation of p53 (6–8). Functional data linking Ing1 with regulation of p53 activity were provided by transfection studies in which forced overexpression of ING1 in cell lines was found to both increase cell sensitivity to DNA double-strand breaks in a p53-dependent manner (9) and induce the expression of certain p53 target genes such as p21 following DNA damage (7). In addition, the ability of exogenous p53 to inhibit cell growth in BALB/c 3T3 cells seems to be compromised in cells partially depleted for ING1 by antisense RNA (6).

These cell-based studies suggest that the negative effects of Ing1 on cell growth are mediated through p53. Furthermore, mutation of ING1 has also been detected in human primary tumors and in tumor-derived cell lines, further underscoring the possibility that ING1 functions as a tumor suppressor (2, 10). In support of this model, mice deleted for Ing1 via gene targeting experiments in embryonic stem cells were recently found to be smaller in size, have reduced viability following whole body irradiation, and display a slight increase in the rate of spontaneous tumor formation relative to wild-type (Wt) mice, particularly in lymphomagenesis (11). However, these Ing1-deficient mouse primary fibroblasts displayed little or no differences in replicative life span or in sensitivity to various forms of genotoxic stress. Thus, the link between Ing1, p53 activity, and tumor suppression remains unclear.

To determine if Ing1 regulates p53 functions in cell growth and tumorigenesis, we generated p37Ing1-deficient mice by using mouse embryonic stem cells bearing a gene trap mutation that specifically ablates p37Ing1. Analysis of p37Ing1-deficient mice and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) revealed that loss of p37Ing1 increased the growth rate of MEFs, providing direct genetic evidence in primary cells that the endogenous level of Ing1 negatively regulates cell proliferation. However, deletion of p37Ing1 also increased the proliferation of p53-deficient MEFs, showing a p53-independent role for p37Ing1 in the control of cell growth. Furthermore, loss of p37Ing1 failed to alter numerous other cell characteristics normally governed by p53, including the rate of primary cell immortalization, oncogene-induced cell senescence, or cell growth arrest following DNA damage by known inducers of p53 activity. In addition, p37Ing1 deletion did not affect the p53-induced embryonic lethality of Mdm2-null mice. These data indicate that p53 remains fully functional in cells lacking p37Ing1, indicating that p37Ing1 down-regulates cell growth in a p53-independent manner.

Although loss of p37Ing1 did not alter the levels of the proapoptotic p53 response gene Puma, p37Ing1 deletion was found to significantly increase Bax gene expression and promote apoptosis following DNA damage in thymocytes irrespective of p53 status, showing that p37Ing1 also has a p53-independent, prosurvival role in apoptosis. Whereas DNA damage–induced apoptosis was up-regulated in p37Ing1-deficient primary cells, mice lacking p37Ing1 developed spontaneous follicular B-cell lymphomas, indicating that p37Ing1 functions as a tumor suppressor in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Generation of p37Ing1b-deficient mice

Mouse (129 strain) embryonic stem cells (Omnibank no. OST206270, Lexicon Genetics, The Woodlands, TX) containing a retroviral promoter gene trap inserted into one allele of Ing1 were used to generate chimeric mice, which were bred to generate p37Ing1-heterozygous mice and subsequent p37Ing1-homozygous mice. Mice were genotyped by PCR analysis of genomic DNA using the following primer sequences: Wt allele, ING1g6673SN: 5′-TCCCCCGTGGAATGTCCTTATC-3′, ING1g7259ASN: 5′-CTGCCAACAGTAGTTCTGAGCAAG-3′; targeted allele, ING1gLTR: 5′-AAATGGCGTTACTTAAGCTAGCTTGC-3′, INGg1874ASN: 5′-CTTGTGGAGAAAAATGCC-3′. A Southern blot strategy using a BglII digest of genomic DNA and a probe to the p31/p37Ing1 common exon was used to confirm the PCR genotyping results. Ing1b-null mice were crossed to Mdm2+/− or p53-null mice and genotyped as previously described (12, 13). All mice were maintained and used in accordance with both federal guidelines and the University of Massachusetts Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell culture and proliferation assay

MEFs were generated from E13.5 day embryos as previously described (14). To determine the rates of cell proliferation, multiple lines of Wt, p53-null, p37Ing1-heterozygous, p37Ing1-null, or p37Ing1 /p53-double null MEFs were seeded at 2 × 105 per 60-mm plate or 1 × 105 per well of a six-well plate. Triplicate plates of each line were harvested and counted every 24 h using a Z1 Coulter Particle Counter (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). Duplicate gelatinized 10-cm plates with 10,000 cells per plate were seeded in MEF medium to assay for cell survival and growth at low plating density. At 8 to 12 days postplating, cells were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.1% crystal violet to visualize colony formation.

Cell immortalization assay

A 3T9 assay was done as described (15) to examine the rate of spontaneous immortalization of Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs. Briefly, 3 × 106 cells were plated into MEF medium on 10-cm plates every 3 days. A total of three plates (9 × 106 cells) were maintained for two separate lines of fibroblasts for each genotype. Triplicate plates for each line were trypsinized before counting and replating at a density of 3 × 106 per 10-cm plate every 3 days.

Cell senescence assay

MEFs were transduced with a recombinant Ras retrovirus as previously described (16) and plated at 2 × 105 per 60-mm plate. Triplicate wells of each of two lines of cells per genotype were harvested and counted every 48 h following initial plating using a Z1 Coulter Particle Counter (Beckman Coulter). Data were expressed as a ratio of the cell number after 6 days in culture versus the cell number at initial plating.

Cell growth arrest studies

MEFs from three independent lines of each genotype were seeded onto 10-cm plates at a density of 8 × 105 per plate in 0.1% fetal bovine serum for 3 days. Cells were then fed with medium supplemented with 10% serum for 4 h, and the cultures left untreated or exposed to 8 Gy of γ-radiation in a cesium irradiator, 300 ng/mL Adriamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or 60 J/cm2 UVC in a UV Crosslinker (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX). At 15 h posttreatment, MEFs were pulse labeled with 60 µmol/L bromodeoxyuridine (BrdUrd) for 3 h, harvested by trypsinization into PBS, and fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. Flow cytometric analysis of DNA synthesis and total DNA content was done using an anti-BrdUrd antibody, propidium iodide staining, and Flowjo software. Data are presented as a ratio of percentage of cells in S phase for treated versus untreated cells.

Apoptosis studies

MEFs transduced with a recombinant retrovirus encoding the adenovirus E1A gene (17) were plated at 106 per 10-cm plate and treated with 0.3 µg/mL of Adriamycin for 24 h. Adherent and nonadherent cells were collected and assayed either for trypan blue exclusion or for propidium iodide staining by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. Wt, p37Ing1-heterozygous, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null mice that were 4 to 6 weeks old were whole-body irradiated with 10 Gy of ionizing radiation, and thymi harvested at 12 h post ionizing radiation. Thymi were ground between frosted glass slides and cells were assayed for viability by trypan blue exclusion. Approximately 106 thymocytes were stained with CD4-phycocyanin (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA; diluted 1:250) and CD8-allophycocyanin (BD PharMingen, diluted 1:100) for 30 min before FACS analysis. For spontaneous apoptosis experiments, single-cell suspensions of thymocytes were plated in RPMI medium with 5% FCS at 106 per 60-mm plate and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 96 h. Plates were harvested, fixed in 70% ethanol, propidium iodide stained, and analyzed by FACS. Ex vivo thymocyte apoptosis experiments were done by plating 106 thymocytes onto 60-mm plates in RPMI medium with 5% FCS and either mock treating or irradiating the plates with 2.5-Gy ionizing radiation. After 4 h, cells were harvested, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by FACS.

Quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR

Relative levels of mRNA expression were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) as previously described (18). cDNA was generated using Invitrogen SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for RT-PCR. The following primer sequences (shown 5′–3′) were used in the PCR reactions: Bcl-2, CTCGTCGCTACCGTCGTGACTTCG and GTGGCCCAGGTATGCACCCAG; Puma, CCTGGAGGGTCATGTACAATCT and TGCTACATGGTGCAGAAAAAGT; and Bax, CTGAGCTGACCTTGGAGC and GACTCCAGCCACAAAGATG. Samples were normalized to EF1α levels present in each tissue as previously described (18).

Tumor assays

A tumor cohort was established for p37Ing1-heterozygous and p37Ing1-homozygous null mice. Moribund mice or those that reached 22 months of age were sacrificed for necropsy, and select tissues harvested for DNA, RNA, and protein. A portion of each tissue was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, and stained with H&E. Tumors were classified by morphology and by immunostaining with antibodies against surface antigen B220 (BD PharMingen, diluted 1:50) or CD-3 (DAKO, Denmark; diluted 1:400).

Results

Generation of p37Ing1-deficient mice

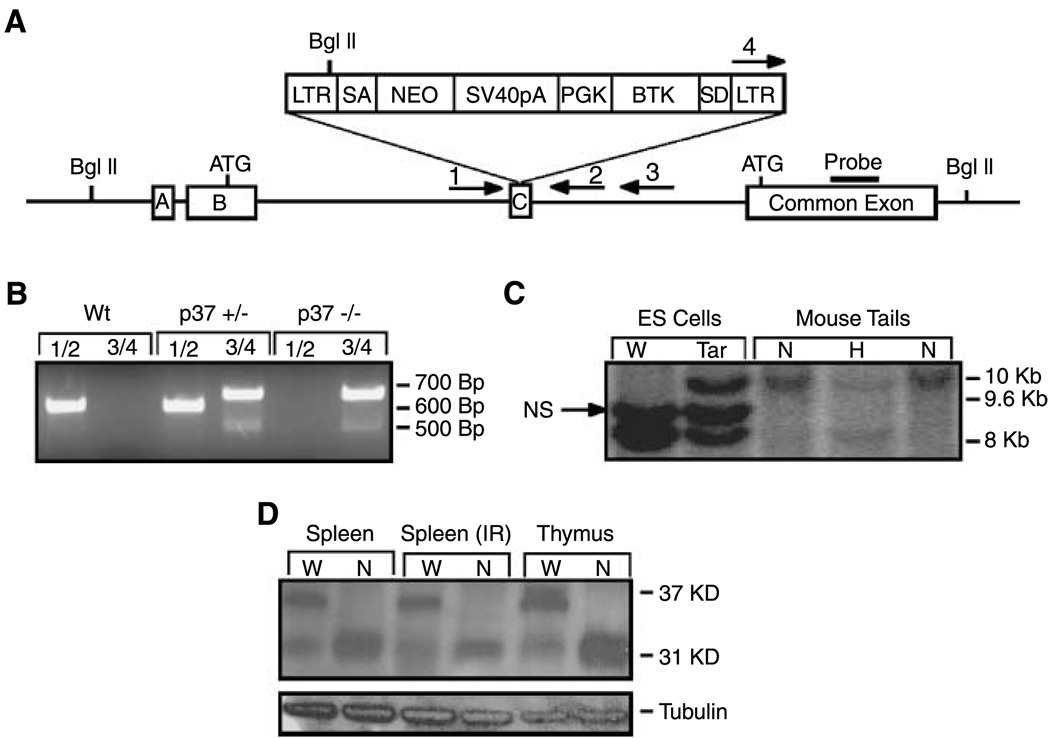

A mouse embryonic stem cell line bearing a retroviral promoter trap inserted into one allele of the Ing1 gene was used in standard blastocyst injection experiments to generate chimeric mice (19). DNA sequence analysis of the gene-trapped locus revealed that the retrovirus inserted into exon C, the third exon of Ing1 (5), interrupting the coding of the longer Ing1b transcript that encodes p37Ing1 (Fig. 1A). Several high-degree chimeric mice were bred with C57Bl/6 mice to generate agouti offspring, and genomic DNA was harvested from tail biopsies and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization (Fig. 1B) and PCR (Fig. 1C) to identify mice that inherited the Ing1-targeted allele. Heterozygous F1 generation mice were intercrossed to obtain mice homozygous for the mutant Ing1 allele, which were recovered with normal Mendelian frequency. Similar to a recent report of mice mutated at the Ing1 locus (11), homozygous mutant mice weighed ~15% less at weaning but were otherwise indistinguishable from the Ing1-heterozygous and Wt littermates. Western blot analysis of Ing1 proteins harvested from the spleens and thymi of Wt and homozygous mutant mice revealed that the homozygous mutant mice retained expression of the p31Ing1 protein in the presence (4 Gy whole body) or absence of DNA damage, but displayed loss of p37Ing1 protein (Fig. 1D). Thus, retroviral insertion into the Ing1 locus in the embryonic stem cells resulted in a p37Ing1-specific knockout allele.

Figure 1.

Generation of p37Ing1-deficient mice. A, schematic of the gene-trapped locus showing the gene trap inserted into exon C. The trap interrupts the Ing1b message isoform and corresponding p37 protein but encodes the shorter Ing1c isoform and p31 protein. B, PCR genotyping of the embryonic stem cells and mouse tail biopsies showing the presence of the gene trap. A 650-bp fragment is generated from Wt Ing1 using primers 1 and 2 and a 700-bp fragment is generated from the targeted Ing1 allele using primers 3 and 4. C, a Southern blot strategy using a BglII digest and a probe to the common exon was used to confirm germ-line transmission of the gene trap. The Wt fragment is ~8 kb and the mutant fragment is ~10 kb in length. A nonspecific (NS) band corresponding to an Ing1 pseudogene present in 129 strain mouse DNA is also observed. D, to confirm that the longer p37Ing1 form was specifically deleted, a Western blot was done with an Ing1 antibody that recognizes sequences encoded in the common exon. The presence of the shorter form (p31) and the absence of the longer form (p37) were observed. Tubulin was used as a loading control.

Negative regulation of cell growth by p37Ing1

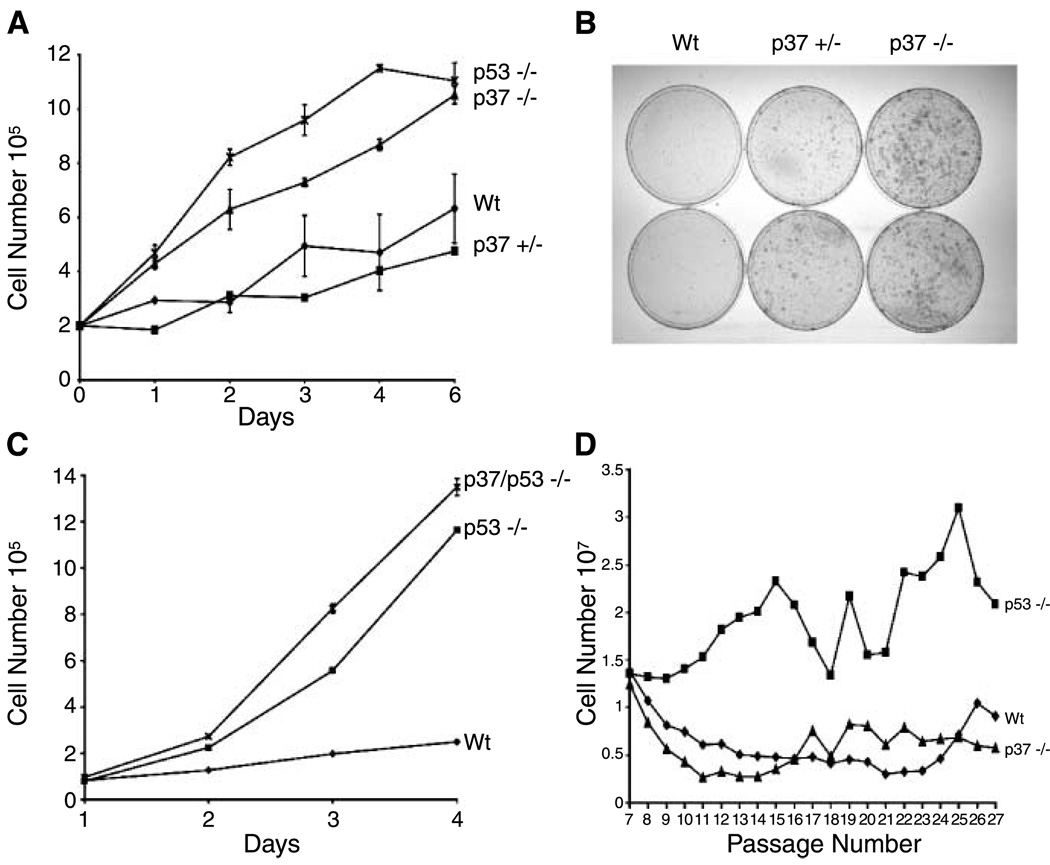

We generated primary fibroblasts from Wt, heterozygous p37Ing1-deficient, and homozygous p37Ing1-deficient embryos to characterize and compare the growth rates of these cells with p53-null MEFs (Fig. 2A). The results indicate that the proliferation rate of p37Ing1-heterozygous MEFs is similar to Wt MEFs. However, p37Ing1-null MEFs proliferate significantly faster than Wt MEFs, although not as fast as MEFs lacking p53. Although p37Ing1-null MEFs displayed Wt plating efficiencies under normal conditions, these cells showed increased survival and growth relative to Wt MEFs when plated at low density (Fig. 2B), similar to results obtained with p53-null MEFs (15). To determine if the down-regulation of cell proliferation by p37Ing1 is mediated through p53, we bred the p37Ing1-deficient mice with p53-null mice (12) and generated p37Ing1/p53-double null MEFs. Analysis of the growth rate of these-double null cells revealed that deletion of p37Ing1 enhanced the growth of p53-deficient primary fibroblasts (Fig. 2C), indicating that the increased proliferation rate of p37Ing1-null MEFs was not due to alteration of p53 activity in these cells.

Figure 2.

Growth regulation byp37Ing1. A, proliferation of p37Ing1-deficient cells. Two independent MEF cell lines of p37Ing1-Wt, p37Ing1-heterozygous, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null genotypes were plated in triplicate in 60-mm plates and growth was analyzed over the course of 7 d. Statistical analysis between Wt and p37Ing1-heterozygous curves shows no significant difference (P < 1.00), but there is statistical difference between Wt and p37Ing1-null curves (P < 0.005). B, growth of p37Ing1-deficient cells at low density. Two lines of Wt, p37Ing1-heterozygous, or p37Ing1-homozygous genotype were seeded at 104 cells per 10-cm plate and incubated for 8 to 12 d before staining with crystal violet. C, growth inhibition by p37Ing1 is independent of p53 status. Three MEF cell lines deficient for p53 or for p53 and p37Ing1 were plated in triplicate in six-well plates and counted over a 7-d period. Wild-type MEFs were also similarly plated as a control. A statistical difference exists between the proliferation rates of p53-null and p37Ing1/p53-double null MEFs (P < 0.0005). D, immortalization of p37Ing1-deficient cells. A 3T9 assay was done using two independent MEF cell lines of p37Ing1-Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs.

Immortalization of p37Ing1 null MEFs

Spontaneous immortalization of MEFs is dependent, in part, on p53 functions. To analyze further the role of p37Ing1 in cell growth, we did a modified 3T3 (3T9) cell immortalization assay. MEFs were generated from Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null embryos and passed continuously in culture following a standard protocol (15). In agreement with our previous reports (15, 20), p53-null MEFs displayed a rapid rate of cell growth throughout the course of the assay relative to Wt MEFs (Fig. 2D). In contrast, p37Ing1-deficient MEFs continued to divide more slowly than p53-null MEFs and never exhibited robust induction of cell growth. Thus, unlike deletion of p53, loss of p37Ing1 does not alter the immortalization rate of primary cultured cells.

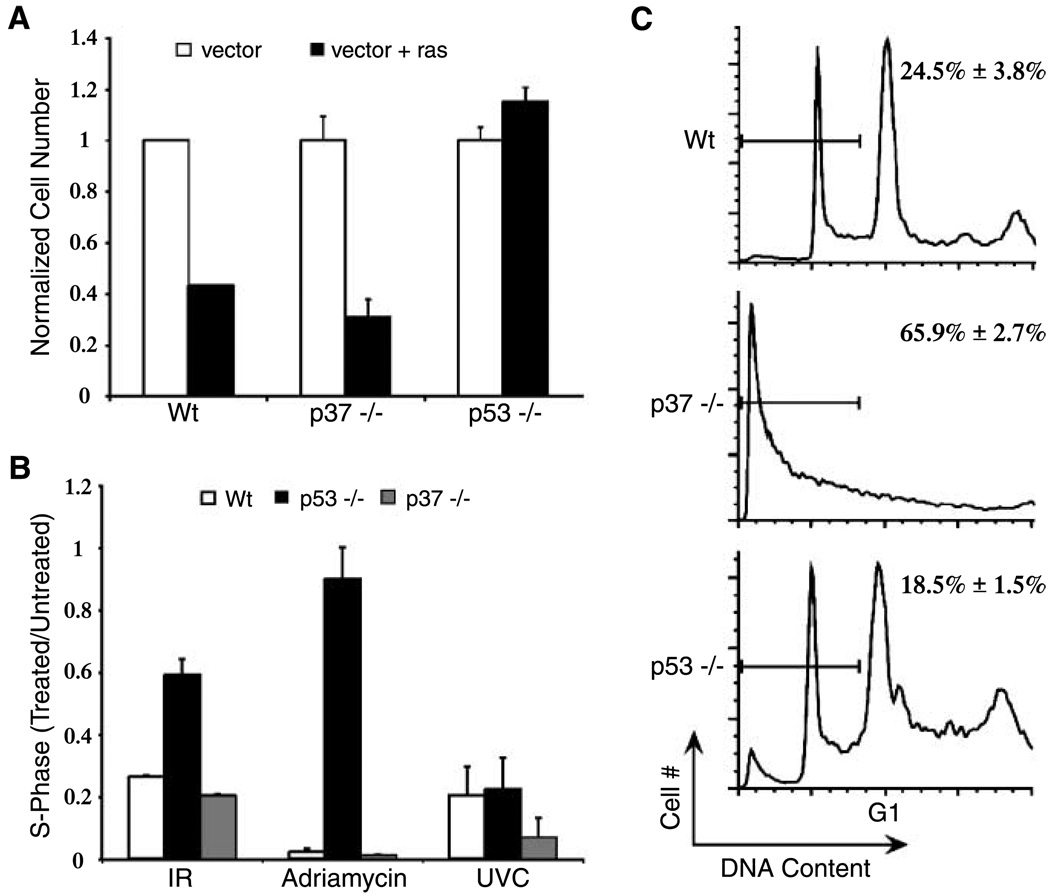

Ras-induced cell senescence in p37Ing1-deficient MEFs

Oncogene-induced stress effects a p53-dependent, replicative senescent phenotype in MEFs (16). To determine if forced expression of an activated ras oncogene induces senescence in p37Ing1-deficient fibroblasts, MEFs that were either Wt, p37Ing1 null, or p53 null were infected with pBABE retrovirus (vector) or with pBABE bearing an activated H-ras gene (vector + ras). After puromycin selection for 72 h, the transduced cells were plated at equal densities and scored for cell growth at day 6 postinfection. Vector alone (no ras) had little effect on the growth of MEFs regardless of genotype (Fig. 3A). As expected, exogenous ras suppressed the growth of Wt MEFs whereas the growth of p53-null MEFs was not affected by activated Ras expression. Similar to Wt MEFs, the growth of p37Ing1-null MEFs was suppressed following oncogene transduction. These data indicate that p53-mediated cell senescence induced by inappropriate oncogene expression in MEFs is unaffected by the presence or absence of p37Ing1.

Figure 3.

Cell cycle arrest and ras-induced senescence are normal in p37Ing1-deficient MEFs, but apoptosis is elevated. A, oncogene-induced senescence in p37Ing1-deficient cells. Triplicate experiments were done wherein multiple lines each of Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs were transduced with recombinant virus with or without H-ras, and cells were plated at equal densities and counted. Columns, ratio of cell number after 6 d in culture versus the cell number at initial plating. B, absence of p37Ing1 does not alter cell cycle arrest due to DNA-damaging agents. Three lines each of wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs were plated in duplicate and synchronized in their growth before mock treatment or treatment with Adriamycin, ionizing radiation, or UVC. Cells were stained with BrdUrd and propidium iodide and analyzed by FACS. Columns, ratio of treated cells in S phase versus untreated cells in S phase. C, triplicate experiments of multiple lines of E1A-transduced MEFs were mock treated or treated with Adriamycin for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by staining with propidium iodide before FACS analysis. Representative result and sub-G1 content derived from three separate experiments. Columns, mean; bars, SD.

Response of p37Ing1-deficient MEFs to DNA damage

Induction of DNA double-strand breaks in MEFs by treatment with ionizing radiation or Adriamycin induces stabilization of p53 and subsequent inhibition of cell growth. To determine if loss of p37Ing1 alters the ability of p53 to arrest cells following DNA damage, Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs were synchronized in their cycling and mock treated or treated with either 8-Gy ionizing radiation or 0.3 µg/mL Adriamycin. The results of this experiment (Fig. 3B) are expressed as the ratio of treated cells in S phase to untreated cells in S phase. As expected, Wt MEFs treated with either ionizing radiation or Adriamycin had a large reduction in the numbers of cells present in the S phase of the cell cycle, whereas p53-null MEFs displayed far less cell growth inhibition following treatment with ionizing radiation or Adriamycin. However, MEFs lacking p37Ing1 were indistinguishable from Wt MEFs in their response to these DNA-damaging agents, indicating that the ability of p53 to induce cell growth arrest in response to DNA double-strand breaks is unaltered in p37Ing1-null MEFs. In addition, Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null MEFs were treated with 60 J/cm2 UVC and assayed for a damage-induced reduction in S phase. Although UVC treatment strongly inhibits cell growth in Wt MEFs, this effect requires functional c-jun NH2-terminal kinase signaling and is not p53 dependent in MEFs (21, 22). Similar to Wt and p53-deficient MEFs, cells lacking p37Ing1 were also growth inhibited by UVC treatment.

Deletion of p37Ing1 does not alter p53-induced lethality in Mdm2-null mice

Mdm2 is a well-established regulator of p53 activity and p53 stability in cells (23, 24), and mice deleted for Mdm2 display an early embryonic lethal phenotype that is rescued by deletion of p53 (13). Recently, the NH2 terminus of p33ING1, the human orthologue of p37Ing1, has been found to complex with the p19-ADP ribosylation factor (ARF) tumor suppressor (25). In cells, p19-ARF regulates p53 activity by binding with Mdm2 and inhibiting Mdm2 ubiquitination of p53 (26). Interaction of p19-ARF and p33ING1 suggests that Ing1 may play a role in p19-Mdm2-p53 signaling, and Ing1 has previously been proposed to alter p53 stability, possibly by interfering with Mdm2-p53 interactions (25).

To explore whether deletion of p37Ing1 alters p53 activity and Mdm2-p53 signaling during development, we bred p37Ing1-null mice with mice bearing a mutated Mdm2 allele (13). Intercrosses of the resulting Mdm2+/−, p37Ing1-null mice were done, and DNA isolated from the offspring (n = 40) of these matings was genotyped to determine Mdm2 status. This experiment failed to generate any Mdm2-null mice (expected n = 10), indicating that the embryonic lethality induced by p53 in the absence of Mdm2 was not dependent on p37Ing1 function. This result is in keeping with our finding that p37Ing1-null MEFs are not compromised in p53-mediated cell growth arrest following DNA damage.

Antiapoptotic role of p37Ing1 in DNA damage response

MEFs transduced with adenovirus E1A undergo p53-induced apoptosis following treatment with Adriamycin (24). To determine if p53 apoptosis was compromised in p37Ing1-null cells, MEFs that were Wt, p53 null, or p37Ing1 null were infected with a recombinant retrovirus encoding both the adenovirus E1A gene and a puromycin resistance gene. Following a 2-day selection in puromycin, E1A-transduced MEFs were recovered, plated in triplicate at equal cell density, and mock treated or treated with 0.3 µg/mL Adriamycin for 24 h. Cell viability was scored by trypan blue exclusion. As expected, Wt MEFs displayed reduced cell viability on treatment with Adriamycin (35.3 ± 4% viable cells), whereas p53-null MEFs were much less susceptible to treatment with this DNA-damaging agent (64.7 ± 4% cell viability). Surprisingly, p37Ing1-null MEFs showed far greater sensitivity to Adriamycin-induced death (9.7 ± 1% viable cells) than Wt cells. To confirm that cell death was due to apoptosis, the experiment was repeated and the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was determined by FACS analysis of the sub-G1 DNA content for each genotype (Fig. 3C). As before, p53-null MEFs were compromised in their ability to undergo apoptosis relative to Wt MEFs, whereas p37Ing1-null MEFs were highly sensitive to the effects of Adriamycin with most of the p37Ing1-null MEFs undergoing apoptosis.

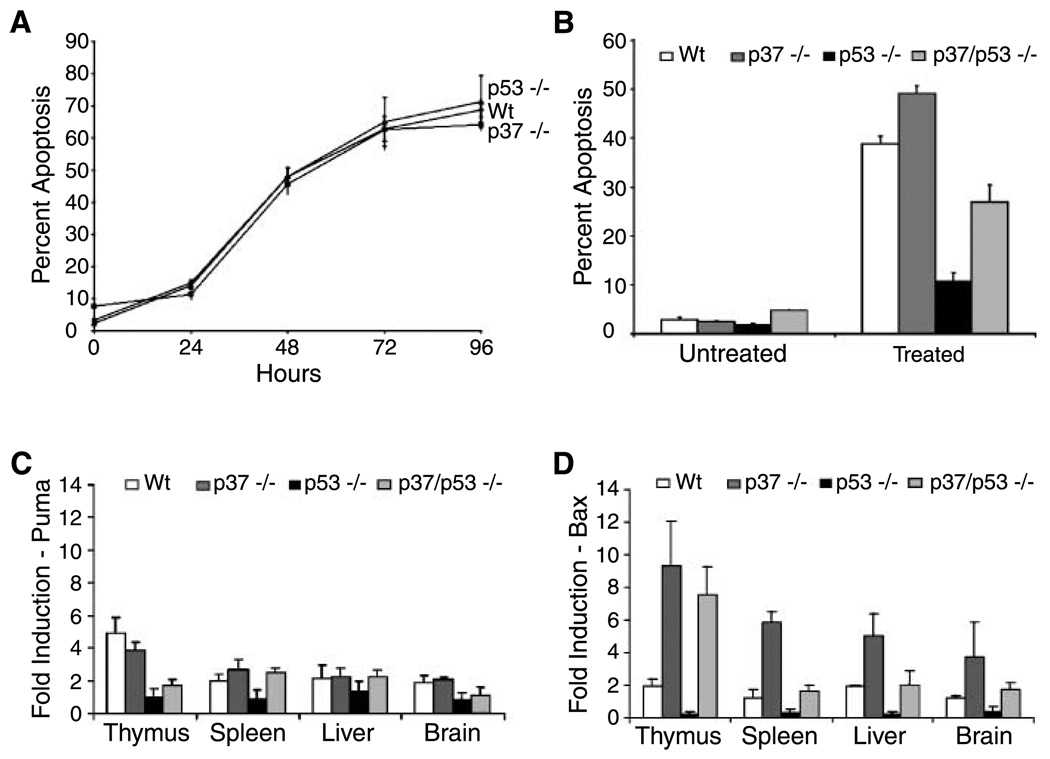

To further explore aberrant apoptosis in p37Ing1-null mice, we isolated thymocytes from 6-week-old Wt, p53-null, or p37Ing1-null mice. The total number of thymocytes recovered from the thymi of p37Ing1-null mice was reduced 2-fold relative to the cell numbers recovered from Wt mice, whereas no differences were observed in the cellularity of the spleens or peripheral lymph nodes in these mice (data not shown). However, Wt, p53-null, and p37Ing1-null thymocytes displayed similar kinetics of cell death when plated in culture (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the spontaneous, non-DNA damage–induced thymocyte death that occurs under these culture conditions is independent of either p53 or p37Ing1 status.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis is altered in p37Ing1-deficient thymocytes. A, spontaneous apoptosis is unchanged in p37Ing1-deficient thymocytes. Thymocytes were isolated from two Wt, p37Ing1-null, or p53-null mice, plated in triplicate, and cultured for 4 d ex vivo. Cells were harvested at 24-h intervals, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stained with propidium iodide and analyzed by FACS. B, thymocytes were isolated from Wt, p37Ing1-null, p53-null, or p37Ing1/p53-double null mice and either mock treated or irradiated with 2.5 Gy of ionizing radiation, fixed in 70% ethanol after 4 h, and stained with propidium iodide for FACS. Columns, average of three separate experiments. The difference in apoptosis between Wt and p37Ing1-null or between p53-null and p37Ing1/p53-double null thymocytes is statistically significant (P < 0.005). C and D, real-time PCR was done with primers to Puma or Bax on tissues harvested from mice that were either mock treated or whole-body treated with 10 Gy of ionizing radiation and harvested 4 h later. Columns, average values (relative fold induction) of three mice for each genotype. The difference in Bax expression is statistically significant between Wt and p37Ing1-null tissues for thymus and spleen (P < 0.05), but not for brain and liver (P < 0.07). The difference in Bax expression between p53-null and p37Ing1/p53-double null tissues is statistically significant for thymus, spleen, and brain (P < 0.05), but not for liver (P < 0.06).

Mouse immature thymocytes (CD4/CD8 double-positive T cells) will undergo p53-dependent apoptosis in response to ionizing radiation (27, 28). To determine if DNA damage–induced cell death is up-regulated in thymocytes lacking p37Ing1, three 4- to 6-week-old mice that were Wt, p53 null, p37Ing1 null, or p37Ing1/p53 double null were whole-body treated with 10-Gy ionizing radiation and thymocytes were recovered at 12 h posttreatment from these mice and from age-matched, nontreated mice. FACS analysis of thymocyte populations stained with CD4 and CD8 antibodies revealed that 45.5 ± 3.1% of the Wt CD4/CD8 double-positive cells survived ionizing radiation treatment, whereas only 31.4 ± 2.1% of the nondamaged levels of p37Ing1-null double-positive T cells were recovered after ionizing radiation treatment. As expected, far more p53-null double-positive T cells survived ionizing radiation damage (78.5 ± 1.4%). However, deletion of p37Ing1 also significantly reduced the survival of p53-null double-positive T cells (56.3 ± 0.3%). These data suggest that p37Ing1 plays a prosurvival role in thymocytes following DNA damage irrespective of p53 status. To confirm that p37Ing1 deletion alters thymocyte apoptosis, thymocytes were harvested from Wt, p53-null, p37Ing1-null, or p53/p37Ing1-double null mice and either untreated or treated with 2.5 Gy of ionizing radiation. Cells were collected 4 h after treatment or mock treatment and analyzed by propidium iodide staining and FACS to measure sub-G1 DNA content (Fig. 4B). In agreement with the findings of the previous E1A-MEF experiments, deletion of p37Ing1 led to increased DNA damage–induced apoptosis in Wt thymocytes. Furthermore, although deletion of p53 correlated with reduced thymocyte apoptosis following ionizing radiation damage, loss of p37Ing1 also resulted in increased apoptosis following DNA damage in p53-null cells, indicating that p37Ing1 has a p53-independent, antiapoptotic role in thymocytes.

To determine if increased apoptosis in p37Ing1-null thymocytes reflected up-regulated expression of the proapoptotic p53 target gene Puma, an important regulator of DNA damage–induced apoptosis in lymphocytes and MEFs (29), the levels of Puma RNA transcripts were measured by quantitative PCR before and after DNA damage. Total RNA was harvested at 4 h posttreatment from the thymi, spleens, livers, and brains of mock-treated or ionizing radiation–treated (10 Gy) mice that were Wt, p53 null, p37Ing1 null, or p53/p37Ing1 double null, and real-time PCR analysis was done to determine the expression levels. As expected, Puma expression was increased in the thymi of Wt mice in response to DNA damage, but not in mice lacking functional p53 (Fig. 4C). However, there was no significant difference in the levels of Puma induction in thymi of Wt mice and p37Ing1-null mice, or in p53-null mice in the presence or absence of p37Ing1.

Bax is also a critical inducer of apoptosis in T cells and in other cell types, but it is not thought to be an important transcriptional target of p53 (30, 31). In keeping with this model, Bax RNA levels were only slightly up-regulated in Wt thymus, spleen, and liver following DNA damage and were unchanged or slightly decreased following ionizing radiation treatment in p53-null samples. In contrast, Bax mRNA levels were induced ~8- to 10-fold after DNA damage in both p37Ing1-null and p37Ing1/p53-double null thymi (Fig. 4D). Induction of Bax expression following DNA damage was also elevated 4- to 6-fold in the spleens, livers, and brains of p37Ing1-null mice and ~2-fold in these tissues in p37Ing1-null mice lacking p53. In addition, levels of Bcl-2 RNA, an antiapoptotic gene, were not significantly altered in these tissues by the presence or absence of either p37Ing1 or p53 (data not shown).

These data suggest that loss of p37Ing1 does not promote thymocyte apoptosis by altering p53 transactivation of Puma following DNA damage. Instead, loss of p37Ing1 leads to up-regulated Bax gene expression following DNA damage of thymocytes irrespective of p53 status.

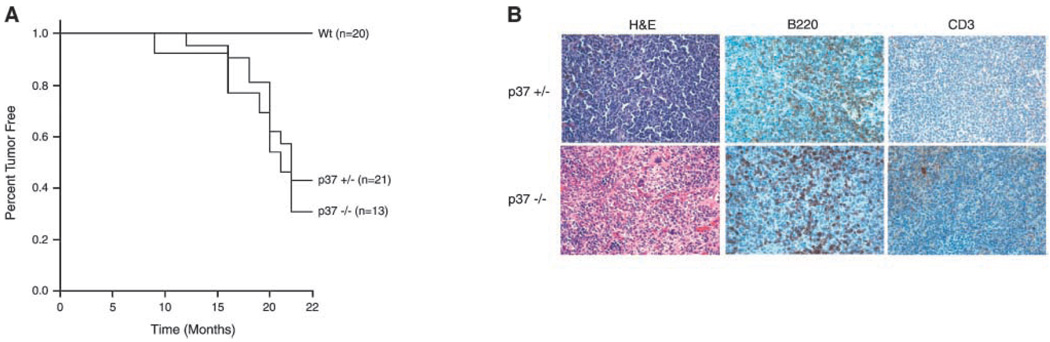

Tumorigenesis in p37Ing1-deficient mice

To determine if mice specifically deleted for p37Ing1 are tumor prone, we generated cohorts of Wt, p37Ing1-heterozygous (p37Ing1+/−), and p37Ing1-null (p37Ing1−/−) mice and monitored these mice for the development of spontaneous tumors. Approximately 40% of the p37Ing1+/− mice and half of the p37Ing1−/− mice formed tumors by 22 months of age, whereas spontaneous tumorigenesis was not observed in the Wt (C57Bl/6 × 129-SV hybrid) mice during this time (Fig. 5A). All of the tumors arose in the spleen or peripheral lymph nodes in these mice and were classified as follicular B-cell lymphomas. Staining of tumor tissues with antibody against B220 or CD3 confirmed that these tumors originated in the B-cell compartment (Fig. 5B) and not in T cells. Thus, although deletion of p37Ing1 does not alter p53 growth control and greatly up-regulates apoptosis in response to DNA damage, p37Ing1 clearly functions as a tumor suppressor in B cells in mice.

Figure 5.

Tumorigenesis in mice deficient for p37Ing1. A, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of cohorts of Wt, p37Ing1-heterozygous, or p37Ing1-null mice. Mice that were either moribund or reached 22 mo of age were sacrificed for necropsy and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin. The rate of tumor incidence between Wt and either p37Ing1-heterozygous or p37Ing1-null mice is statistically significant (P < 0.005 or P < 0.05, respectively). B, tumors arising in mice were paraffin embedded and H&E stained for pathologic analysis. Tumor sections were also stained with either B220 or CD3 antibodies to determine tissue of tumor origin.

Discussion

ING family members are highly conserved, PHD-containing proteins that are linked to chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation through their association with histone acetyl transferase and histone deacetylase complexes (2, 32–34). Previous studies have implicated Ing1 (or human ING1) as an important regulator of numerous aspects of mammalian cell physiology, including cell growth, apoptosis, senescence, and tumorigenesis (2). The Ing1 gene encodes for three alternatively spliced isoforms of Ing1 message: Ing1a and Ing1c encode a 31-kDa protein and Ing1b encodes for a 37-kDa protein in mice (p33 kDa in human). Forced Ing1b overexpression or antisense RNA knockdown experiments in cultured cells have indicated that p37Ing1 (or p33ING) and p53 coimmunoprecipitate and can function in a synergistic manner to inhibit cell growth or promote apoptosis following DNA damage (5–7). Furthermore, some ING proteins, including p33ING, have been proposed to regulate cellular p53 levels by modifying p53 interactions with components of the p19-Mdm2-p53 signaling pathway (2, 8). In addition to altering p53 activity, transfection experiments have also suggested possible p53-independent roles for ING1b in the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis (4, 35).

In this study, we generated p37Ing1-deficient mice and primary cells to examine the role of this p53-binding protein in the regulation of cell growth, cell death, and tumorigenesis. Specific deletion of p37Ing1 in MEFs increases the rate of cell proliferation and growth at low plating densities, confirming that physiologic levels of an Ing protein can function to inhibit cell growth in primary cells. However, this regulation does not seem to involve p53 because deletion of p37Ing1 also increases the proliferation of MEFs lacking p53. Furthermore, p37Ing1-deficient MEFs fail to exhibit perturbation of other cell growth parameters governed by p53, including spontaneous cell immortalization, oncogene-induced senescence, or cell cycle arrest following DNA damage. In addition, deletion of p37Ing1 failed to rescue the p53-dependent embryonic lethality seen in Mdm2-null mice, offering further support that loss of p37Ing1 does not seem to compromise p53 activities in cells or in mice.

Human ING1b (p33ING1) has previously been proposed to play a proapoptotic role in fibroblasts (4, 36). In contrast, analysis of apoptosis in p37Ing1-deficient MEFs indicates that physiologic levels of p37Ing1 strongly inhibit apoptosis in these cells following DNA damage. To confirm a prosurvival role for p37Ing1 following DNA damage, we analyzed ionizing radiation–induced apoptosis in primary thymocytes and in thymus tissue in vivo. As expected, apoptosis was decreased in cells lacking p53 following DNA damage. However, apoptosis was increased in thymocytes both in vitro and in vivo in p37Ing1-deficient cells, in keeping with our previous results in primary fibroblasts. Notably, apoptosis was dramatically increased in thymocytes isolated from both p37Ing1-deficient mice and p37Ing1/p53-double null mice following DNA damage. Thus, in contrast to the proapoptotic role of p53 in these cells, p37Ing1 plays an antiapoptotic role in thymocytes following DNA damage that is clearly p53 independent.

Puma is a p53 transcriptional target validated in vivo as important regulator of apoptosis following DNA damage (29). In thymocytes, p53-mediated apoptosis is governed primarily through Puma activation because mice deleted for either Puma or p53 are equally deficient in ionizing radiation–induced thymocyte apoptosis. However, Puma expression was equally up-regulated in Wt and p37Ing1-null thymocytes following DNA damage, further supporting a p53-independent role for p37Ing1 in the suppression of apoptosis. Bax, another critical regulator of mitochondrial-associated apoptosis, functions by altering permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Deletion of p37Ing1 dramatically increased up-regulation of Bax expression in vivo in both Wt and p53-null thymocytes following DNA damage. Loss of p37Ing1 also up-regulated Bax levels to a lesser extent in spleen, liver, and brain tissues. Increased levels of Bax induction in p37Ing1-deficient mice following DNA damage occurred independent of p53 status in all tissues, confirming a p53-independent role for p37Ing1 in suppressing Bax expression following DNA damage.

The results of our study indicate that p37Ing1 suppresses cell proliferation in the presence or absence of p53 and does not alter p53-mediated cell growth arrest following DNA damage. In addition, p37Ing1 negatively regulates Bax levels in vivo and functions as a prosurvival molecule following DNA damage in thymocytes regardless of p53 status. These data suggest that p37Ing1 might also suppress tumor formation in a p53-independent manner. Interestingly, all of the tumors that arose in the p37Ing1-deficient colonies were classified as follicular B-cell lymphoma. This tumor type is rarely observed in p53-null mice (12), which present mainly with thymic lymphomas and osteosarcomas, offering further support that p53 and p37Ing1 may suppress tumorigenesis through different mechanistic pathways. Furthermore, whereas there is a significant acceleration of tumorigenesis in mice haploinsufficient or deleted for p37Ing1, the onset of tumors in heterozygous or homozygous p37Ing1-null mice is similar, suggesting that any reduction in p37Ing1 levels might promote spontaneous tumor formation.

Recently, mice lacking both p37Ing1 and p31Ing1 have been analyzed (11). The p37Ing1/p31Ing1–deficient mice undergo normal development but have reduced body size and present with spontaneous tumors later in life. In addition, MEFs derived from p37Ing1/p31Ing1–deficient mice display little or no changes in cell cycling after treatment with Taxol or other DNA-damaging agents. As these characteristics are also observed in p37Ing1-deficient mice, it is possible that loss of p37Ing1 is the underlying cause of the defects observed in the p37Ing1/p31Ing1–deficient mice and cells. However, in addition to B-cell lymphomas, histiocytic sarcomas and myeloid leukemias were also observed in p37Ing1/p31Ing1–deficient mice, suggesting that the p31Ing1 protein may also have unique tumor-suppressing properties. Interestingly, expression of p31Ing1 seems to be slightly elevated in mice lacking the p37Ing1 isoform. Therefore, it is also possible that up-regulation of p31Ing1 may contribute in some way to the increased proliferation and DNA damage–induced apoptosis observed in p37Ing1-ablated cells and mice. However, any contribution of increased p31Ing1 levels to the phenotype of p37Ing1-deficient mice and cells must also be p53 independent.

The results of this study show a p53-independent role for p37Ing1 in the negative regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis and highlight a role for p37Ing1 in the suppression of B-cell lymphomagenesis. Furthermore, the data indicate that loss of p37Ing1 correlates with increased Bax expression in thymocytes following DNA damage. Although up-regulation of Bax has been found to also increase cell proliferation in some settings (37, 38), it is possible that increased apoptosis in p37Ing1 null thymocytes might prevent tumor formation in this tissue. Further work will be needed to better characterize the role of Bax in the p37Ing1 regulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis, and B-cell lymphomagenesis.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Program project grant P30DK32529 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and NIH grant CA77735 from the National Cancer Institute (S.N. Jones).

We thank David Garlick and members of the University of Massachusetts Medical School Morphology Core for assistance with pathology; Richard Konz and the University of Massachusetts Medical School Flow Cytometry Core for help with thymocyte analysis; Joy Riley and Judy Gallant in the University of Massachusetts Medical School Transgenic Animal Modeling Core for assistance with blastocyst injections; Jianyan Luo for helpful discussion; and Charlene Baron for assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Garkavtsev I, Kazarov A, Gudkov A, Riabowol K. Suppression of the novel growth inhibitor p33ING1 promotes neoplastic transformation. Nat Genet. 1996;14:415–420. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos EI, Chin MY, Kuo WH, Li G. Biological functions of the ING family tumor suppressors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2597–2613. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4199-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goeman F, Thormeyer D, Abad M, et al. Growth inhibition by the tumor suppressor p33ING1 in immortalized and primary cells: involvement of two silencing domains and effect of Ras. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:422–431. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.1.422-431.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helbing CC, Veillette C, Riabowol K, Johnston RN, Garkavtsev I. A novel candidate tumor suppressor, ING1, is involved in the regulation of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1255–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeremski M, Hill JE, Kwek SS, et al. Structure and regulation of the mouse ing1 gene. Three alternative transcripts encode two phd finger proteins that have opposite effects on p53 function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32172–32181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garkavtsev I, Grigorian IA, Ossovskaya VS, et al. The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control. Nature. 1998;391:295–298. doi: 10.1038/34675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kataoka H, Bonnefin P, Vieyra D, et al. ING1 represses transcription by direct DNA binding and through effects on p53. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5785–5792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leung KM, Po LS, Tsang FC, et al. The candidate tumor suppressor ING1b can stabilize p53 by disrupting the regulation of p53 by MDM2. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4890–4893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung KJ, Li G. p33(ING1) enhances UVB-induced apoptosis in melanoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2002;279:291–298. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouman GS, Anderson JJ, Lunec J, Angus B. The role of the tumour suppressor p33 ING1b in human neoplasia. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:491–496. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.7.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kichina JV, Zeremski M, Aris L, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse ing1 locus results in reduced body size, hypersensitivity to radiation and elevated incidence of lymphomas. Oncogene. 2006;25:857–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, et al. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones SN, Roe A, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature. 1995;378:206–208. doi: 10.1038/378206a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harvey M, Sands AT, Weiss RS, et al. In vitro growth characteristics of embryo fibroblasts isolated from p53-deficient mice. Oncogene. 1993;8:2457–2467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferbeyre G, de Stanchina E, Lin AW, et al. Oncogenic ras and p53 cooperate to induce cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:3497–3508. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.10.3497-3508.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinman HA, Hoover KM, Keeler ML, Sands AT, Jones SN. Rescue of Mdm4-deficient mice by Mdm2 reveals functional overlap of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in development. Oncogene. 2005;24:7935–7940. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marfella CGA, Ohkawa Y, Coles AH, Garlick DS, Jones SN, Imbalzano AN. Mutation of the SNF2 family member Chd2 affects mouse development and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:162–171. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zambrowicz BP, Friedrich GA, Buxton EC, Lilleberg SL, Person C, Sands AT. Disruption and sequence identification of 2,000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1998;392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones SN, Sands AT, Hancock AR, et al. The tumorigenic potential and cell growth characteristics of p53-deficient cells are equivalent in the presence or absence of Mdm2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14106–14111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, et al. Requirement of JNK for stress-induced activation of the cytochrome c-mediated death pathway. Science. 2000;288:870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attardi LD, de Vries A, Jacks T. Activation of the p53-dependent G1 checkpoint response in mouse embryo fibroblasts depends on the specific DNA damage inducer. Oncogene. 2004;23:973–980. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balint EE, Vousden KH. Activation and activities of the p53 tumour suppressor protein. BJC. 2001;85:1813–1823. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.González L, Freije JM, Cal S, López-Otín C, Serrano M, Palmero I. A functional link between the tumour suppressors ARF and p33ING1. Oncogene. 2006;25:5173–5179. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe SW, Sherr CJ. Tumor suppression by Ink4a-Arf: progress and puzzles. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:77–83. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clarke AR, Purdie CA, Harrison DJ, et al. Thymocyte apoptosis induced by p53-dependent and independent pathways. Nature. 1993;362:849–852. doi: 10.1038/362849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe SW, Schmitt EM, Smith SW, Osborne BA, Jacks T. p53 is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in mouse thymocytes. Nature. 1993;362:847–849. doi: 10.1038/362847a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chipuk JE, Maurer U, Green DR, Schuler M. Pharmacologic activation of p53 elicits Bax-dependent apoptosis in the absence of transcription. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doyon Y, Cayrou C, Ullah M, et al. ING tumor suppressor proteins are critical regulators of chromatin acetylation required for genome expression and perpetuation. Mol Cell. 2006;21:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng X, Hara Y, Riabowol K. Different HATS of the ING1 gene family. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:532–538. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02391-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nourani A, Doyon Y, Utley RT, Allard S, Lane WS, Cote J. Role of an ING1 growth regulator in transcriptional activation and targeted histone acetylation by the NuA4 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7629–7640. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.22.7629-7640.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsang FC, Po LS, Leung KM, Lau A, Siu WY, Poon RY. ING1b decreases cell proliferation through p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 2003;553:277–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott M, Bonnefin P, Vieyra D, et al. UV-induced binding of ING1 to PCNA regulates the induction of apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3455–3462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.19.3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brady HJ, Gil-Gomez G, Kirberg J, Berns AJ. Baxα perturbs T cell development and affects cell cycle entry of T cells. EMBO J. 1996;15:6991–7001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gil-Gomez G, Berns A, Brady HJ. A link between cell cycle and cell death: Bax and Bcl-2 modulate Cdk2 activation during thymocyte apoptosis. EMBO J. 1998;17:7209–7218. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]