Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole for irritability in pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and Asperger's disorder.

Method

This is a 14-week, prospective, open-label investigation of aripiprazole in 25 children and adolescents diagnosed with PDD-NOS or Asperger's disorder. Primary outcome measures included the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) scale and the Irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC-I).

Results

Twenty-five subjects, ages 5–17 years (mean 8.6 years) received a mean final aripiprazole dosage of 7.8 mg/day (range 2.5–15 mg/day). Full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) scores ranged from 48 to 122 (mean 84). Twenty-two (88%) of 25 subjects were responders in regard to interfering symptoms of irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums, with a final CGI-I of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved) and a 25% or greater improvement on the ABC-I. The final mean CGI-I was 1.6 (p ≤ 0.0001). ABC-I scores ranged from 18 to 43 (mean 29) at baseline, whereas scores at week 14 ranged from 0 to 27 (mean 8.1) (p ≤ 0.001). Aripiprazole was well tolerated. Mild extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) were reported in 9 subjects. Age- and sex-normed body mass index (BMI) increased from a mean value of 20.3 at baseline to 21.1 at end point (p ≤ 0.04). Prolactin significantly decreased from a mean value of 9.3 at baseline to 2.9 at end point (p ≤ 0.0001). No subject exited the study due to a drug-related adverse event.

Conclusions

These preliminary data suggest that aripiprazole may be effective and well tolerated for severe irritability in pediatric patients with PDD-NOS or Asperger's disorder. Larger-scale placebo-controlled studies are needed to elucidate the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole in this understudied population.

Introduction

Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and Asperger's disorder are understudied neuropsychiatric disorders characterized by core social and communication impairments and repetitive interests and activities (American Psychiatric Association 2000). Moreover, severe irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums are observed frequently and can have a significant impact on the affected individual and his or her family (Dawson et al. 1998; Stigler et al. 2002; Towbin 2005). Despite numerous treatment studies in autistic disorder (autism), research focused specifically on the pharmacotherapy of PDD-NOS and Asperger's disorder is greatly lacking (McDougle et al. 2006). Recent epidemiological surveys of PDDs suggest that their prevalence may be increasing, with conservative estimates of autism at 13/10,000, Asperger's disorder at 2.6/10,000, and PDD-NOS at 20.8/10,000 (Fombonne 2005). These findings have heightened awareness regarding the various subtypes of PDDs.

The atypical antipsychotics have been the most studied class of medication for the treatment of irritability in PDDs. Encouraging open-label studies of risperidone, olanzapine, and ziprasidone, as well as relatively negative studies of quetiapine have been published for PDDs (Findling et al. 1997; McDougle et al. 1997; Nicolson et al. 1998; Martin et al. 1999; Potenza et al. 1999; Malone et al. 2001; Masi et al. 2001; McDougle et al. 2002; Corson et al. 2004; Findling et al. 2004; Hardan et al. 2005; Malone et al. 2007).

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-sponsored Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network conducted the first double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of an atypical antipsychotic for symptoms of irritability in pediatric subjects with autism (RUPP Autism Network 2002). In this 8-week study, 101 children and adolescents (mean age 8.8 years) received risperidone at a mean dosage of 1.8 mg/day. Response to risperidone was robust, with 69% of treatment subjects considered responders compared to 12% of the placebo group. Risperidone was associated with significant weight gain (2.7 kg vs. 0.8 kg for placebo). Although standardized measures of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia (TD) were not significantly different between groups, drooling was reported more frequently in subjects receiving risperidone. In a subsequent report, 63 subjects who responded to the 8-week trial of risperidone continued on 16-weeks of open-label treatment (RUPP Autism Network 2005). Only 8% discontinued treatment due to lack of efficacy or adverse effects. A second large double-blind, placebo-controlled study of risperidone (mean dose 1.2 mg/day) for irritability was conducted in 79 children (age range 5–12 years) with PDDs (Shea et al. 2004). In this 8-week study, 54% of risperidone-treated patients compared to 18% receiving placebo were considered responders. The mean weight gain was 2.7 kg in the risperidone group and 1 kg in the placebo group.

Recently, risperidone was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with autism. Although the use of risperidone for the treatment of irritability (aggression, self-injury, tantrums) in PDDs is supported, the compound is a full dopamine (DA) D2 antagonist and, as a result, is associated with specific adverse effects, including EPS and hyperprolactinemia (Anderson et al. 2007). Combining these adverse effects with the risk of significant weight gain that can occur in association with risperidone, there remains a need for effective, better-tolerated pharmacotherapies in PDDs (Aman et al. 2005).

Aripiprazole is a novel agent that is a partial DA D2 and serotonin (5-HT)1A agonist, and a 5-HT2A antagonist (Burris et al. 2002; Jordan et al. 2002). The drug has high affinity for DA D2 and D3, 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A, and moderate affinity for DA D4, 5-HT2C, 5-HT7, α1-adrenergic, and histamine H1 receptors, as well as the 5-HT reuptake site. Aripiprazole is hypothesized to function as an agonist or antagonist, depending on the receptor population and local concentrations of DA (Tamminga 2001).

Researchers have recently embarked upon investigations of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders. Retrospective studies suggesting the effectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole in youth with bipolar disorder (Barzman et al. 2004; Biederman et al. 2005), as well as developmental disorders with co-morbid diagnoses including PDDs, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), reactive attachment disorder, and sleep disorders (Valicenti-McDermott et al. 2006) have been published.

In addition to retrospective studies, case reports have been published on the use of aripiprazole in children and adolescents. A prospective naturalistic case series of aripiprazole (mean dose 12 mg/day, range 10–15 mg/day) was conducted in 5 youths with PDDs (mean age 12.2 years, range 5–18 years) (Stigler et al. 2004). Over a mean duration of 12 weeks (range 8–16 weeks), all subjects were judged as treatment responders based on a score of much or very much improved on the Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement scale (CGI-I). Significant improvement was recorded in aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. No EPS were noted. Sedation was reported in 2 youths. Overall, subjects lost weight (mean change −3.7 kg; range −13.6 to + 0.45 kg), likely due to the discontinuation of treatment with prior atypical antipsychotics associated with weight gain. In another case report, Storch and colleagues (2007) reported on an adolescent male (13 years) with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) who had an incomplete response to combined sertraline and cognitive behavior therapy. The addition of aripiprazole (maximum dose 5 mg/day) over approximately 6 months resulted in a significant reduction in symptomatology. No clinically significant changes in weight or laboratory measures were recorded.

Several prospective, open-label trials have also been conducted, including an 8-week study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with bipolar I disorder (Biederman et al. 2007). In this study, aripiprazole (mean dose 9.4 mg/day) resulted in significant improvement on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). Two cases of EPS led to early termination. No statistically significant increase in weight was recorded. Yoo et al. (2006) conducted an 8-week pilot study of aripiprazole (mean dosage 10.9 mg/day, range 2.5–15 mg/day) in 14 youths (mean age 11.9 years, range 7–17 years) with Tourette disorder. A significant decrease of 40.1% was found on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) Total Tic score. Overall, the drug was well tolerated. The group subsequently published a larger 8-week study of aripiprazole (mean dose 9.8 mg/day, range 2.5–20 mg/day) in 24 subjects aged 7–18 years (mean age 11.8 years) with a tic disorder (Yoo et al. 2007). Treatment was associated with a 52.8% reduction in the YGTSS Total Tic score, with 19 subjects (79.2%) considered much or very much improved on the CGI-I. The drug was prematurely discontinued in 6 subjects due to adverse effects such as nausea or sedation. There were no significant changes in weight. A 12-week study of aripiprazole (mean dosage 8.2 mg/day, range 2.5–15 mg/day) in 15 subjects (mean age 12.2 years, range 7–19 years) with Tourette disorder or chronic tic disorder found significant decreases on YGTSS scores (Seo et al. 2008). Nausea and sedation were common adverse effects. No significant difference was recorded in the mean body mass index (BMI).

In regard to double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of aripiprazole that have been conducted in youths, data were presented on the efficacy of the drug in 302 adolescents (mean age 15.5 years, range 13–17 years) with schizophrenia (Robb et al. 2007). The study was a 6-week trial in which subjects were randomized to placebo or a fixed dose of 10 mg or 30 mg of aripiprazole daily. The study found both doses of aripiprazole superior to placebo at week 6. Overall, the drug was well tolerated, with similar discontinuation rates in the aripiprazole and placebo groups (Findling et al. 2007). The most common adverse effects were somnolence and EPS, which were higher in the 30 mg/day group. The mean change in weight from baseline was considered minimal (10 mg, no change; 30 mg, 0.2 kg; placebo, −0.8 kg). Aripiprazole is FDA-approved for the acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in adolescents aged 13–17 years.

Placebo-controlled research has also been conducted in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder (Nyilas et al. 2008). A 4-week multicenter trial of aripiprazole was completed in 296 patients aged 10–17 years with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, manic or mixed, with or without psychotic features. The subjects were randomly assigned to two fixed doses of aripiprazole (10 mg/day or 30 mg/day) or placebo. Both doses were superior to placebo as measured from baseline to week 4 on the YMRS. Common adverse effects included somnolence, EPS, fatigue, and nausea. Mean change in weight from baseline to week 4 was 0.6 kg, 0.9 kg, and 0.5 kg for aripiprazole 10 mg/day, 30 mg/day, and placebo, respectively. These findings, combined with others (Chang et al. 2007; Correll et al. 2007; Wagner et al. 2007), support the use of aripiprazole in this population. The drug has FDA approval for the acute and maintenance treatment of manic and mixed episodes in youth with bipolar I disorder, ages 10–17 years.

Recently, data from an 8-week, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study were presented on the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole (mean dosage 8.5 mg/day, range 2–15 mg/day) in 98 children and adolescents, aged 6–17 years, with autism (Owen et al. 2008a). Aripiprazole was found to be significantly superior to placebo on both the CGI-I and Aberrant Behavior Checklist–Irritability subscale (ABC-I). Common adverse effects included somnolence, fatigue, increased appetite, drooling, and tremor. Subjects in the aripiprazole group had a mean weight gain of 1.9 kg versus 0.5 kg in the placebo group. However, there was no significant difference in change in BMI between aripiprazole and placebo. The authors concluded that the drug was efficacious and generally safe and well tolerated in the treatment of irritability in this population. Another study presented by Owen et al. (2008b) was conducted in 218 children and adolescents (6–17 years) with autism and associated irritability. In this 8-week, multicenter, fixed-dose, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, subjects were randomized to aripiprazole (5, 10, or 15 mg/day) or placebo. Significantly greater improvement was seen in all three aripiprazole groups versus placebo as measured by the CGI-I and ABC-I. Common adverse effects included sedation, fatigue, increased appetite, vomiting, drooling, and tremor. Subjects in the aripiprazole group gained an average of 1.5 kg (5 mg/day), 1.4 kg (10 mg/day), and 1.6 kg (15 mg/day) versus 0.4 kg in the placebo group. There was a significant difference in change in BMI between aripiprazole and placebo at the 15-mg/day dosage (0.7 and 0.2, respectively) (p ≤ 0.02). Overall, aripiprazole was reported as efficacious for irritability and was generally safe and well tolerated.

This prospective, open-label study sought to determine the effectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole for the treatment of irritability in children and adolescents with PDD-NOS and Asperger's disorder. We hypothesized that aripiprazole would be effective for reducing severe irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. We also hypothesized that aripiprazole would be well tolerated, with a low risk for EPS, hyperprolactinemia, and weight gain. In addition, we expected that this open-label trial would serve to stimulate more definitive, controlled research in these understudied diagnostic subgroups.

Methods

Participants

The Indiana University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study. Twenty-five children and adolescents, aged 5–17 years, were enrolled. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant's legal guardian, and subjects provided assent when able. Diagnoses of PDD-NOS or Asperger's disorder using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) criteria were made by a board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrist experienced in the assessment and diagnosis of PDDs. Subjects were required to have a mental age of at least 18 months, as determined by the Wechsler Intelligence Scales (Wechsler 1999) or Leiter International Test of Intelligence–Revised (Roid and Miller 1997). Participants were required to be physically healthy, as well as free of all psychotropic medications for at least 2 weeks (4 weeks for fluoxetine). Additional inclusion criteria included a CGI–Severity (S) scale (Guy 1976) score of at least 4 (“Moderately Ill”) focused specifically on target symptoms of irritability (aggression, self-injury, tantrums); and a score ≥ 18 on the ABC-I (Aman et al. 1985; Aman and Singh 1994). Subjects with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of another PDD, other primary psychiatric disorder, active seizure disorder, significant medical condition, positive urine pregnancy test, or history of neuroleptic malignant syndrome were excluded.

Study design

A 14-week, prospective, open-label study design was chosen to gather pilot data on aripiprazole in children and adolescents with PDD-NOS or Asperger's disorder in anticipation of larger-scale, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies in this population. The study duration allowed for gradual titration, as well as an 8-week maintenance phase. All subjects underwent a screening and baseline visit. Follow-up visits occurred every two weeks during the 14-week open-label trial period.

Dosing

All subjects initially received 1.25 mg/day of aripiprazole for 3 days. The dosage was then increased to 2.5 mg/day and continued to the end of week 2. The investigators then increased the dosage to a maximum of 15 mg/day over the next 4 weeks, if optimal clinical response had not occurred and intolerable adverse effects had not emerged. The dosage maintenance phase lasted 8 weeks at the optimal dosage.

Measures

The CGI-S was administered at baseline as part of the eligibility criteria described above. In this study, the rater scored the CGI-S in regard to severity of irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. The CGI-S is rated from 1 to 7 (1 = normal, not at all ill; 2 = borderline ill; 3 = mildly ill; 4 = moderately ill; 5 = markedly ill; 6 = severely ill; 7 = among the most extremely ill patients).

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the CGI-I and the ABC-I. The CGI-I is a scale designed to assess global change from baseline. The CGI-I ranges from 1 to 7 (1 = very much improved; 2 = much improved; 3 = minimally improved; 4 = no change; 5 = minimally worse; 6 = much worse; 7 = very much worse). In this study, the CGI-I score was focused on improvement in the target symptoms of irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. The ABC-I is a subscale of the ABC, which is an informant-rated measure of severity of irritability commonly observed in PDDs. The ABC-I was used as a primary outcome measure in the aforementioned studies by the RUPP Autism Network (2002, 2005) and Shea and colleagues (2004). The ABC has confirmed reliability and validity in regard to the factor structure, distribution of scores, and sensitivity to change (Aman et al. 1985; Brown et al. 2002). The Irritability subscale consists of 15 items on temper tantrums, aggression, mood swings, irritability, property destruction, and self-injury. The CGI-I and ABC-I were administered at every visit after baseline.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures included the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) (Sparrow et al. 2005) and the Compulsion Subscale of the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for PDDs (CY-BOCS-PDD) (Scahill et al. 2006). The VABS, a normed parent interview designed to measure functional competence in daily living activities, were administered at baseline and end point. The VABS provide scores for Communication, Socialization, Daily Living Skills, and Motor Skills, as well as an Adaptive Behavior Composite. The VABS Maladaptive Behavior subscales (Part 1 and Part 2) were also completed by staff during the parent interview. Part 1 includes 27 items related to symptoms of aggression, withdrawal, impulsivity, tantrums, inattention, emotionality, and defiance. Part 2 consists of 9 items including self-injury, property destruction, mannerisms, preoccupations, and rocking.

The CY-BOCS-PDD is a semistructured clinician-rated instrument that measures repetitive behavior in individuals with PDDs (Scahill et al. 2006). A modified version of the CY-BOCS, this measure retains the compulsions checklist from the original CY-BOCS and expands upon it to include repetitive behaviors commonly seen in children with PDDs. In this study, restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior were measured at baseline and end point with the CY-BOCS-PDD.

Safety assessment and monitoring

Prior to entry into the study, all subjects underwent a medical history and full psychiatric examination. A physical examination was completed at baseline and end point. Vital signs, height, and weight were obtained at each visit. Laboratory testing including CBC with differential and platelet count, electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, liver function tests (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT], serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase [SGPT], total bilirubin, direct bilirubin), prolactin, and fasting glucose and lipid profiles were obtained at baseline and week 14. Urinalyses, including urine pregnancy test in females of childbearing potential, and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) with rhythm strip were obtained at baseline and end point. A pediatric cardiologist formally read every ECG. Adverse effects were systematically reviewed at each clinic visit by the investigators, and the Simpson–Angus Rating Scale (Simpson and Angus 1970) and Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (Guy 1976) were administered. In addition, the Side Effects Review Form, a listing of potential adverse effects common to aripiprazole, was completed.

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and entered into SAS (Littell et al. 1996). Data were analyzed according to the intent-to-treat principle (last observation carried forward [LOCF]). Unless otherwise specified, data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), with results considered significant when p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed). Subjects were considered treatment responders if they had a CGI-I score of 1 or 2, and a ≥25% improvement on the ABC-I. Analysis was based on SAS Proc Mixed. A linear mixed model with random slope and intercept was fitted to these data. A linear mixed model is a general linear regression framework that takes into account correlations among samples either from a longitudinal or clustering setting. The outcome variables were the scores, and they were regressed on time after drug therapy. Paired t-tests were calculated to determine change from baseline to the end of week 14 of aripiprazole treatment for the VABS and CY-BOCS-PDD.

Weight analysis

In regard to analysis of change in weight, due to the length of this study, weight would be expected to increase over time in growing children and adolescents. Thus, rather than using change in weight, in this study age- and sex-adjusted BMI was used to determine change in body composition more accurately. The BMIs were then transformed to standardized z scores, which permits the quantitative tracking of all subjects, via the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention age- and sex-normed growth charts (http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts; Martin et al. 2004). Paired t-tests were used to determine change between baseline and end point for BMIs and z scores.

Results

Of 39 subjects screened, 25 (64%) met eligibility criteria and were enrolled. The sample consisted of 19 males and 6 females, aged 5–17 years (mean 8.6 years), consistent with the higher male-to-female ratio observed in PDDs. Twenty-one subjects were diagnosed with PDD-NOS and 4 subjects were diagnosed with Asperger's disorder. Twenty two (88%) of 25 participants were Caucasian. Minority subjects included African-American (n = 2) and Asian (n = 1) youths. Full scale intelligence quotient (IQ) scores ranged from 48 to 122, with a mean score of 84. Subjects received a mean final aripiprazole dosage of 7.8 mg/day (range 2.5–15 mg/day).

Twenty two of 25 (88%) subjects completed the study. The remaining 3 subjects were included in the analysis according to LOCF. They had completed either 6 weeks (n = 1) or 8 weeks (n = 2) of treatment with aripiprazole prior to exiting the study. One subject withdrew due to their parent's request for their child to resume prior medication for anxiety (in addition to aripiprazole for irritability) and another subject was withdrawn by their parent secondary to ineffectiveness of the medication. One subject with a history of seizure disorder exited from the study due to a possible seizure described as “shakiness.” Poststudy electroencephalography (EEG) was remarkable for a pattern consistent with “prematurity of birth,” and the subject's neurologist concluded that the reported “seizure-like” activity was not related to study drug.

Treatment response

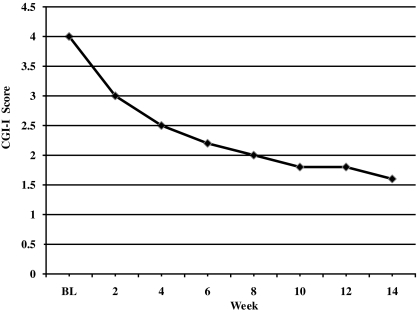

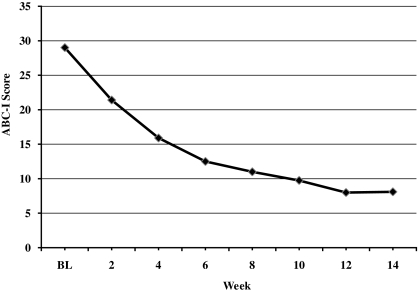

Twenty-two (88%) of 25 subjects were considered responders, as determined by a CGI-I score of 1 or 2 and a ≥25% improvement on the ABC-I. All 4 subjects diagnosed with Asperger's disorder were responders to treatment, whereas 18 of 21 (86%) subjects with PDD-NOS responded. The mean CGI-I score at end point was 1.6 ± 0.9, with 22 (88%) of 25 subjects rated as much or very much improved in regards to interfering target symptoms of irritability (aggression, self-injury, tantrums) (p ≤ 0.0001) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). ABC-I scores ranged from 18 to 43 (mean score, 29 ± 7.3) at baseline, whereas scores at week 14 ranged from 0 to 27 (mean score, 8.1 ± 7.5) (p ≤ 0.001) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). When a linear mixed model with random slope and intercept was fitted to the data, the drug effect on the CGI-I and ABC-I was −0.124 unit-change/week (standard error [SE] = 0.01; p ≤ 0.0001) and −1.45 unit-change/week (SE = 0.14; p ≤ 0.0001), respectively.

FIG. 1.

Change in mean CGI-I score. Assigned baseline score of 4 (“no change”). CGI-I, Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement; BL, baseline.

Table 1.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Measure Results

| Measure | Baseline (mean ± SD) | End point (mean ± SD) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) | 4.0 ± 0.0b | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 0.0001 |

| Aberrant Behavior Checklist–Irritability (ABC-I) | 29 ± 7.3 | 8.1 ± 7.5 | 0.001 |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS) | |||

| Communication | 80.6 ± 13 | 80.7 ± 14.7 | 0.97 |

| Motor skills | 90.7 ± 19.1 | 91.8 ± 14.9 | 0.71 |

| Daily living skills | 69.4 ± 20.4 | 72.8 ± 13.7 | 0.2 |

| Socialization | 72.4 ± 12.8 | 83.6 ± 15.2 | 0.0001 |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Composite | 69.6 ± 12.8 | 74.2 ± 12.6 | 0.036 |

| Maladaptive Domain Part I | 26.2 ± 5.3 | 14.6 ± 7.5 | 0.0001 |

| Maladaptive Domain Part II | 6.3 ± 3.4 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.0001 |

| Maladaptive Total (Part I + Part II) | 32.6 ± 7.8 | 16.2 ± 8.3 | 0.0001 |

| Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Modified for PDD (CY-BOCS-PDD) | 11.9 ± 2 | 6.8 ± 4.1 | 0.0001 |

Statistical analyses: CGI-I and ABC-I = linear mixed model; VABS and CY-BOCS-PDD = paired t-test.

Assigned baseline of “no change.”

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; PDD = pervasive developmental disorder.

FIG. 2.

Change in mean ABC-I score. ABC-I, Aberrant Behavior checklist–Irritability subscale; BL, baseline.

Response on secondary measures

In regard to the VABS standard scores, significant changes were recorded on the Socialization domain, which improved from 72.4 ± 12.8 at baseline to 83.6 ± 15.2 at end point (p ≤ 0.001), whereas no significant changes were found on the Communication, Motor Skills, or Daily Living Skills Domains. The Adaptive Behavior Composite improved from 69.6 ± 12.8 at baseline to 74.2 ± 12.6 at end point (p ≤ 0.036). Significant improvement was also recorded on Part 1 (from 26.2 ± 5.3 to 14.6 ± 7.5 [p ≤ 0.0001]) and Part 2 (from 6.3 ± 3.4 to 1.6 ± 1.2 [p ≤ 0.0001]) of the Maladaptive Behavior subscales. In addition, the total score of the Maladaptive Behavior subscales (Part I + Part II) improved from 32.6 ± 7.8 to 16.2 ± 8.3 (p ≤ 0.0001). The Compulsion Subscale score of the CY-BOCS-PDD was also found to improve significantly from baseline (11.9 ± 2) to end point (6.8 ± 4.1) (p ≤ 0.0001). Table 1 summarizes these data.

Safety measures and adverse effects

No clinically significant changes in heart rate or blood pressure were recorded during the study. In addition, no clinically significant changes were found between baseline and end point on ECG measures, including the QTc interval, which decreased from 413.6 ± 17.9 (baseline) to 410.6 ± 16.4 (end point) (p = 0.28). Prolactin levels decreased significantly over the 14 weeks, from 9.3 ± 5.2 at baseline to 2.9 ± 3.4 at end point (p ≤ 0.0001). During the study, 19 of 25 (76%) subjects gained weight (mean + 2.7 kg, range −3.3 to +8.1 kg), with mean age- and sex-adjusted BMIs increasing from 20.3 ± 6.1 at baseline to 21.1 ± 5.7 at end point (p ≤ 0.04). Age- and sex-normed z scores increased from a mean of 0.94 ± 1.2 at baseline to 1.2 ± 1.2 at end point (p ≤ 0.03). Fasting glucose levels increased nonsignificantly over the 14 weeks, from 87.2 ± 9.5 to 91.8 ± 10.2 mg/dL (p = 0.06) (Indiana University [I.U.] reference range, 70–109 mg/dL]. Two subjects had glucose levels that exceeded 109 mg/dL at end point, with one subject having a value of 112 mg/dL and the other subject having a value of 111 mg/dL; neither subject was fasting. Mean fasting lipid measures obtained at baseline and end point revealed no significant changes. However, 1 subject had an increase from baseline to end point in total cholesterol (187 to 216) (I.U. reference range, ≤200) and low-density lipoprotein () (118–142) (I.U. reference range, ≤100), 1 subject had an increase in LDL (116–139), and another subject had an increase in triglycerides (135–184) (I.U. reference range, ≤150); all subjects were fasting. Table 2 summarizes these data. Other test results, including laboratory testing and urinalyses (as described in Methods) showed no clinically significant changes.

Table 2.

Selected Safety Measures

| Measure | Baseline (mean ± SD) | End point (mean ± SD) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| QTc interval | 413.6 ± 17.9 | 410.6 ± 16.4 | 0.28 |

| Prolactin | 9.3 ± 5.2 | 2.9 ± 3.4 | 0.0001 |

| Fasting lipid panel | |||

| Total cholesterol | 156.4 ± 28.5 | 159.2 ± 28.7 | 0.64 |

| HDL | 48.9 ± 14.8 | 47.3 ± 14.9 | 0.67 |

| LDL | 93.3 ± 24.1 | 93.4 ± 27.9 | 0.98 |

| Triglycerides | 71.3 ± 45.4 | 73.6 ± 40.3 | 0.77 |

| Fasting glucose | 87.2 ± 9.5 | 91.8 ± 10.2 | 0.06 |

Statistical analyses: paired t-test.

Abbreviations: SD = standard deviation; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein.

Aripiprazole was well tolerated overall, with no severe or serious adverse effects recorded during the study. Assessment with the Simpson–Angus Rating Scale and the AIMS revealed no EPS, and no benztropine or diphenhydramine was necessary during the study. However, caregivers reported mild sialorrhea (n = 4), mild tremor (n = 2), and mild sialorrhea and mild tremor (n = 1), mild sialorrhea and muscle stiffness (n = 1), as well as moderate neck stiffness and mild tremor (n = 1). The most common adverse events as reported by caregivers included mild tiredness (n = 14), cough (n = 12), increased appetite (n = 11), nausea/vomiting (n = 10), and rhinitis (n = 10) (Table 3). None of the adverse effects was treatment limiting. No subject exited the study due to a drug-related adverse event.

Table 3.

Caregiver Reported Adverse Effects of Aripiprazole Treatment

| Adverse Event | Mild (n) | Moderate (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Tiredness | 14 | 1 |

| Cough | 12 | |

| Increased appetite | 11 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 10 | |

| Rhinitis | 10 | |

| Constipation | 7 | 2 |

| Diarrhea | 9 | |

| Dry mouth | 8 | |

| Dyspepsia | 8 | |

| Weight gain | 8 | |

| Trouble waking up | 8 | |

| Headaches | 4 | 3 |

| Sialorrhea | 6 | |

| Rash | 4 | |

| Tremor | 4 | |

| Anxiety | 2 | 1 |

| Enuresis | 3 | |

| Decreased appetite | 2 | |

| Dysuria | 2 | |

| Trouble falling asleep | 2 | |

| Blood in stool | 1 | |

| Decreased urination | 1 | |

| Dizziness | 1 | |

| Fever | 1 | |

| Hematuria | 1 | |

| Knee pain | 1 | |

| Lip biting | 1 | |

| Muscle stiffness | 1 | |

| Nasal congestion | 1 | |

| Neck stiffness | 1 | |

| “Seizure”a | 1 | |

| Sinusitis | 1 | |

| Tearfulness | 1 | |

| Tinnitus | 1 |

Note: The greatest severity reported by each subject is recorded.

See text.

Abbreviations: n = number of subjects.

Discussion

The results of this 14-week prospective, open-label study suggest that aripiprazole may be effective and well tolerated for targeting irritability in pediatric patients with PDD-NOS. Although the drug may also be effective in patients with Asperger's disorder, our small sample size limits interpretation of data in this PDD subtype. Treatment with aripiprazole at dosages from 2.5 to 15 mg/day resulted in significant improvement in irritability, including aggression, self-injury, and tantrums. In light of research suggesting that a dysregulation of DA and 5-HT contributes to maladaptive behavior in PDDs (McDougle et al. 2005), aripiprazole's unique mechanism of action as a partial DA D2 and 5-HT1A agonist, and 5-HT2A antagonist, may prove to be important for both its effectiveness and tolerability in PDDs.

The significant reduction found on the ABC-I subscale from baseline to end point is noteworthy in that the subjects in this study had higher baseline irritability subscale scores than those in the RUPP Autism Network study of risperidone for irritability in autism (RUPP Autism Network 2002). This finding highlights that youth with PDDs other than autism, such as PDD-NOS, often suffer from a significant degree of similar symptomatology (Dawson et al. 2002). It also demonstrates the potential marked effectiveness of aripiprazole in targeting severe irritability in this understudied subtype of PDD. In addition to the improvement found on the ABC-I, significant improvement was recorded on the Vineland Maladaptive Behavior subscales (Part I and Part 2), which also assess symptoms of irritability such as aggression, self-injury, and tantrums.

Treatment with aripiprazole was found to improve impaired socialization as measured by the VABS Socialization domain. Significant improvement on the standard score of the VABS Socialization domain was observed in a relatively brief period of time. This is of particular importance because standardized scores are unlikely to show significant change with such a short treatment duration (Michael Aman, Ph.D., and Eric Butter, Ph.D., personal communication). Indeed, our finding of positive change in socialization with aripiprazole as measured by the standard score of the VABS Socialization domain was not observed in the RUPP Autism Network study of risperidone (Williams et al. 2006). Although highly speculative, it may be that we observed these positive changes in socialization due to aripiprazole's mechanism of action as a partial 5-HT1A agonist (Jordan et al. 2002). A putative association has been hypothesized between partial agonism at 5-HT1A receptors and improvements in anxiety and depression, as well as negative symptoms of schizophrenia (Millan 2000). Thus, it is possible that aripiprazole may have targeted these symptoms, thereby potentially resulting in an increased ability and/or interest of the subject to interact with others. It also may be that by decreasing irritability, the children and adolescents were better able to improve their social functioning over time. In addition to the Socialization domain, The VABS Adaptive Composite scores demonstrated overall improvement, also suggesting that a decrease in irritability might allow for better compliance regarding adaptive behavior.

The improvement noted on the CY-BOCS-PDD is also of interest because children and adolescents diagnosed with a PDD often struggle with associated repetitive behaviors and interests. McDougle and colleagues (2005) reported a baseline CY-BOCS Compulsion subscale score of 15.5 and an end point score of 11.6 in subjects receiving risperidone in the RUPP Autism Network study (2002); this is a statistically significant decrease. Although baseline CY-BOCS-PDD scores were not as severe in this higher functioning group of subjects (baseline 11.9, end point 6.8), there clearly was a significant decrease observed in repetitive symptoms by week 14. Repetitive behaviors are also observed in OCD and Tourette's disorder. The ability of aripiprazole to target repetitive behavior in this study is supported by preliminary evidence suggesting that the drug may be beneficial in the treatment of repetitive behaviors in OCD and Tourette's disorder (Yoo et al. 2006; De Rocha et al. 2007; Friedman et al. 2007; Storch et al. 2007; Yoo et al. 2007).

In terms of safety measures, ECGs revealed no clinically significant changes, including the QTc interval. Prolactin was found to decrease significantly from baseline to week 14. It is possible that aripiprazole's mechanism of action as a partial dopamine agonist may have resulted in the lowering of prolactin observed during this study. Although no EPS were recorded during this study using standardized physician-administered measures, they were reported by parents in 9 subjects, highlighting that EPS may occur with the use of aripiprazole in this population. In regard to weight gain, to date, a generally accepted definition of clinically significant weight gain does not exist for youths (Correll et al. 2006). However, use of standardized BMI z scores permits the quantitative tracking of all subjects based on age- and gender-normed indices (Martin et al. 2004). Correll and colleagues (2006) proposed a threshold of ≥0.5 increase in BMI z score for any duration greater than 12 weeks as indicative of a significant increase in body composition in youth. In this study, although there was an increase in the mean BMI z score, the change was only 0.26, which is approximately 50% less than the threshold proposed by Correll et al. (2006). Although this suggests that the amount of weight gain was not outside of the expected range for growing youth over this treatment duration, a mean weight gain of 2.7 kg did occur during this 14-week study. Longer-term, placebo-controlled studies are needed to better understand whether aripiprazole treatment is associated with clinically significant weight gain in children and adolescents. Fasting glucose measures did not rise beyond the upper limit of the normal range; however, mean values did increase over the 14-week study. These findings suggest a need for longer-term, controlled studies to better understand any potential effects of aripiprazole on fasting glucose measures in this population. Aside from 3 subjects, aripiprazole was not associated with clinically significant changes in lipid measures. Overall, aripiprazole was well tolerated, with no severe or serious adverse effects associated with the drug. As shown in Table 3, the majority of adverse effects were mild.

This study has several limitations that could potentially impact the reliability and validity of these findings. Because of its open-label design, bias as well as a placebo effect could be a factor in our findings of improvement in irritability as well as socialization. In this study, diagnoses were made by child and adolescent psychiatrists experienced in the diagnosis of PDDs using DSM-IV-TR criteria. However, it will be important to incorporate additional diagnostic instruments into future studies to augment the diagnostic assessment of individuals with subtypes of PDDs, such as PDD-NOS. The number of subjects in this study was relatively small. In addition, the absence of a control group limits any conclusions that can be definitively drawn regarding the safety and tolerability of aripiprazole in this population.

Despite these inherent limitations, the preliminary results of this study suggest that aripiprazole has the potential to be an effective and well-tolerated treatment for severe irritability in pediatric patients with PDD-NOS, and possibly in Asperger's disorder. In addition, the improvement in socialization observed with aripiprazole treatment is intriguing and deserves further study. Taken together, these favorable initial findings are of particular clinical relevance given the high prevalence of children and adolescents diagnosed with PDD-NOS. In fact, PDD-NOS is the most common subtype of PDD and worthy of more formal investigation, given the impairment it bestows upon those who have it (Fombonne 2005; Towbin 2005). Controlled research and longitudinal studies are needed to further determine the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole for the treatment of irritability in this greatly understudied PDD subtype.

Footnotes

This study was supported, in part, by an American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Pilot Research Award (Dr. Stigler), a Daniel X. and Mary Freedman Fellowship in Academic Psychiatry (Dr. Stigler), an investigator-initiated research grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. (Drs. Stigler and McDougle), the National Institutes of Health (K12 UL1 RR025761, Dr. Erickson), and the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH68627, Dr. Posey; R01 MH072964, Dr. McDougle).

Disclosures

Dr. Stigler has affiliations with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., and Janssen Pharmaceutica. Mr. Diener, Ms. Kohn, and Dr. Li have no financial ties or conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Erickson has affiliations with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. and F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., and Seaside Therapeutics. Dr. Posey has affiliations with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Eli Lilly and Co., Forest Research Institute, and Shire. Dr. McDougle has affiliations with Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., F. Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd., and Forest Research Institute.

References

- Aman MG. Singh NN. East Aurora (New York): Slosson Educational Publications; 1994. Supplement to Aberrant Behavior Checklist Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG. Singh NN. Stewart AW. Field CJ. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: A behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. 1985;89:485–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman MG. Arnold LE. McDougle CJ. Vitiello B. Scahill L. Davies M. McCracken JT. Tierney E. Nash PL. Posey DJ. Chuang S. Martin A. Shah B. Gonzalez NM. Swiezy NB. Ritz L. Koenig K. McGough J. Ghuman JK. Lindsay RL. Acute and long term safety and tolerability of risperidone in children with autism. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:565–569. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM. Scahill L. McCracken JT. McDougle CJ. Aman MG. Tierney E. Arnold LE. Martin A. Katsovich L. Posey DJ. Shah B. Vitiello B. Effects of short- and long-term risperidone treatment on prolactin levels in children and adolescents with autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzman DH. DelBello MP. Kowatch RA. Garnert B. Fleck DE. Pathak S. Rappaport K. Delgado SV. Campbell P. Strakowski SM. The effectiveness and tolerability of aripiprazole for pediatric bipolar disorder: A retrospective chart review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:593–600. doi: 10.1089/cap.2004.14.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J. McDonnell MA. Wozniak J. Spencer T. Aleardi M. Falzone R. Mick E. Aripiprazole in the treatment of pediatric bipolar disorder: A systematic chart review. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:141–148. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J. Mick E. Spencer T. Doyle R. Joshi G. Hammerness P. Kotarski M. Aleardi M. Wozniak J. An open-label trial of aripiprazole monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:683–689. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900021519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EC. Aman MG. Havercamp SM. Factor analysis and norms on parent ratings with the Aberrant Behavior Checklist: Community for young people in special education. Res Dev Disabil. 2002;23:45–60. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(01)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris KD. Molski TF. Xu C. Ryan E. Tottori K. Kikuchi T. Yocca FD. Molinoff PB. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang KD. Nyilas M. Aurang C. Johnson MS. Jin N. Marcus R. Forbes RA. Carson WH. Kahn A. Findling RL. Boston (MA): 54th American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Meeting; 2007. Efficacy of aripiprazole in children (10–17 years old) with mania. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU. Carlson HE. Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:771–791. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220851.94392.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU. Nyilas M. Aurang C. Johnson B. Jin N. Marcus R. Pikalov A. McQuade RD. Iwamoto T. Weller E. Boston (Massachusetts): 54th American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Meeting; 2007. Safety, tolerability of aripiprazole in children (10–17) with mania. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Corson AH. Barkenbus JE. Posey DJ. Stigler KA. McDougle CJ. A retrospective analysis of quetiapine in the treatment of pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1531–1536. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JE. Matson JL. Cherry KE. An analysis of maladaptive behaviors in persons with autism, PDD NOS, and mental retardation. Res Dev Disabil. 1998;19:439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(98)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G. Webb S. Shellenberg GD. Dager S. Friedman S. Aylward E. Richards T. Defining the broader phenotype of autism: Genetic, brain, and behavioral perspectives. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14:581–611. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rocha FF. Correa H. Successful augmentation with aripiprazole in clomipramine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (letter to the editor) Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31:1550–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL. Maxwell K. Wiznitzer M. An open clinical trial of risperidone monotherapy in young children with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL. McNamara NK. Gracious BL. O'Riordan MA. Reed MD. Demeter C. Blumer JL. Quetiapine in nine youths with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:287–294. doi: 10.1089/1044546041649129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL. Robb AS. Nyilas M. Forbes RA. McQuade RD. Mallikaarjun S. Pikalov A. San Diego (California): American Psychiatric Association 160th Annual Meeting; 2007. Tolerability of aripiprazole in the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 10):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S. Abdallah TA. Oumaya M. Rouillon F. Guelfi JD. Aripiprazole augmentation of clomipramine-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder (letter to the editor) J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:972–973. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0624d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. Washington (DC): DHEW, NIMH; 1976. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology (NIMH Publication No. 76–338) [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY. Jou RJ. Handen BL. Retrospective study of quetiapine in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35:387–391. doi: 10.1007/s10803-005-3306-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S. Koprivica V. Chen R. Tottori K. Kikuchi T. Altar CA. The antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;441:137–140. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC. Milliken GA. Stroup WW. Wolfinger RD. Cary: SAS Inst. Inc.; 1996. SAS system for mixed models; pp. 31–63. [Google Scholar]

- Malone RP. Cater J. Sheikh RM. Choudhury MS. Delaney MA. Olanzapine versus haloperidol in children with autistic disorder: An open-pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:887–894. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone RP. Delaney MA. Hyman SB. Cater JR. Ziprasidone in adolescents with autism: An open-label pilot study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17:779–790. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. Koenig K. Scahill L. Bregman J. Open-label quetiapine in the treatment of children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 1999;9:99–107. doi: 10.1089/cap.1999.9.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. Scahill L. Anderson GM. Aman M. Arnold LE. McCracken J. McDougle CJ. Tierney E. Chuang S. Vitiello B. The Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network: Weight and leptin changes among risperidone-treated youths with autism: 6-month prospective data. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1125–1127. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi G. Cosenza A. Mucci M. Brovedani P. Open trial of risperidone in 24 young children with pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1206–1214. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ. Holmes JP. Bronson MR. Anderson GM. Volkmar FR. Price LH. Cohen DJ. Risperidone treatment of children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders: A prospective, open-label study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:685–693. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ. Kem DL. Posey DJ. Case series: Use of ziprasidone for maladaptive symptoms in youths with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:921–927. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ. Erickson CA. Stigler KA. Posey DJ. Neurochemistry in the pathophysiology of autism. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl):9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougle CJ. Posey DJ. Stigler KA. Pharmacological treatments. In: Moldin SO, editor; Rubenstein JLR, editor. Understanding Autism: From Basic Neuroscience to Treatment. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: Focus on serotonin (5-HT)1A receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:853–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolson R. Awad G. Sloman L. An open trial of risperidone in young autistic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;41:921–927. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199804000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyilas M. Chang K. Forbes RA. Jin N. Johnson B. Owen R. Pikalov A. McQuade RD. Iwamoto T. Carson WH. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association 161st Annual Meeting; 2008. Acute efficacy, tolerability of the treatment of bipolar I disorder in pediatric patients. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Owen R. Findling RL. Carlson G. Nyilas M. Iwamoto T. Mankoski R. Assuncao-Talbott S. Carson WH. McQuade R. Oren DA. Chicago (Illinois): 55th American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Meeting; 2008a. Efficacy, safety of aripiprazole in the treatment of serious behavioral problems associated with autistic disorder in children, adolescents (6–17 years old): Results from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Owen R. Marcus R. Aman MG. Manos G. Mankoski R. Assuncao-Talbott S. Nyilas M. Iwamoto T. Carson W. Oren DA. Chicago (Illinois): 55th American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Meeting; 2008b. Efficacy, safety of aripiprazole in the treatment of serious behavioral problems associated with autistic disorder in children, adolescents (6–17 years old): Results from a fixed-dose, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN. Holmes JP. Kanes SJ. McDougle CJ. Olanzapine treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with pervasive developmental disorders: An open-label pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:37–44. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network. Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:314–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology (RUPP) Autism Network. Risperidone treatment of autistic disorder: Longer term benefits and blinded discontinuation after 6 months. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1361–1369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb AS. Findling RL. Nyilas M. Forbes R. McQuade RD. Mallikaarjun S. Pikalov A. Marcus R. Carson WH. San Diego (California): American Psychiatric Association 160th Annual Meeting; 2007. Efficacy of aripiprazole in the treatment of adolescents with schizophrenia. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH. Miller LJ. Wood Dale (Illinois): Stoelting Company; 1997. Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L. McDougle CJ. Williams SK. Dimitropoulos A. Aman MG. McCracken JT. Tierney E. Arnold LE. Cronin P. Grados M. Ghuman J. Koenig K. Lam KS. McGough J. Posey DJ. Ritz L. Swiezy NB. Vitiello B. Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network: Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale modified for pervasive developmental disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1114–1123. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220854.79144.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo WS. Sung HM. Sea HS. Bai DS. Aripiprazole treatment of children and adolescents with Tourette disorder or chronic tic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:197–205. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S. Turgay A. Carroll A. Schulz M. Orlik H. Smith I. Dunbar F. Risperidone treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e634–e641. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0264-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GM. Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS. Cicchetti DV. Balla DA. (Vineland II), Survey Interview Form/Caregiver Rating Form. Second. Livonia (Minnesota): Pearson Assessments; 2005. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler KA. Posey DJ. McDougle CJ. Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of autism. Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics. 2002;2:499–510. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stigler KA. Posey DJ. McDougle CJ. Aripiprazole for maladaptive behavior in pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:455–463. doi: 10.1089/cap.2004.14.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA. Lehmkuhl H. Gefken GR. Touchton A. Murphy TK. Aripiprazole augmentation of incomplete treatment response in an adolescent male with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25:172–174. doi: 10.1002/da.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA. Partial dopamine agonists in the treatment of psychosis. J Neural Transm. 2001;109:411–420. doi: 10.1007/s007020200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin KE. Pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified. In: Volkmar FR, editor; Paul R, editor; Klin A, editor; Cohen D, editor. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 165–200. [Google Scholar]

- Valicenti-McDermott MR. Demb H. Clinical effects and adverse reactions of off-label use of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:549–560. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KD. Nyilas M. Johnson B. Aurang C. Forbes A. Marcus R. Carson WH. Iwamoto T. Carlson GA. Boston (Massachusetts): 54th American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Meeting; 2007. Long-term efficacy of aripiprazole in children (10–17 years old) with mania. (poster). [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. 3rd. San Antonio (Texas): Psychological Corporation; 1999. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. [Google Scholar]

- Williams SK. Scahill L. Vitiello B. Aman MG. Arnold LE. McDougle CJ. McCracken JT. Tierney E. Ritz L. Posey DJ. Swiezy NB. Hollway J. Cronin P. Ghuman J. Wheeler C. Cicchetti D. Sparrow S. Risperidone and adaptive behavior in children with autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:431–439. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000196423.80717.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HK. Kim JY. Kim CY. Letter to the Editor: A pilot study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with Tourette's disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:505–506. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HK. Choi SH. Park S. Wang HR. Hong JP. Kim CY. An open-label study of the efficacy and tolerability of aripiprazole for children and adolescents with tic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1088–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]