Abstract

Actin-depolymerizing-factor (ADF)/cofilins have emerged as key regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics in cell motility, morphogenesis, endocytosis, and cytokinesis. The activities of ADF/cofilins are regulated by membrane phospholipid PI(4,5)P2 in vitro and in cells, but the mechanism of the ADF/cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction has remained controversial. Recent studies suggested that ADF/cofilins interact with PI(4,5)P2 through a specific binding pocket, and that this interaction is dependent on pH. Here, we combined systematic mutagenesis with biochemical and spectroscopic methods to elucidate the phosphoinositide-binding mechanism of ADF/cofilins. Our analysis revealed that cofilin does not harbor a specific PI(4,5)P2-binding pocket, but instead interacts with PI(4,5)P2 through a large, positively charged surface of the molecule. Cofilin interacts simultaneously with multiple PI(4,5)P2 headgroups in a cooperative manner. Consequently, interactions of cofilin with membranes and actin exhibit sharp sensitivity to PI(4,5)P2 density. Finally, we show that cofilin binding to PI(4,5)P2 is not sensitive to changes in the pH at physiological salt concentration, although the PI(4,5)P2-clustering activity of cofilin is moderately inhibited at elevated pH. Collectively, our data demonstrate that ADF/cofilins bind PI(4,5)P2 headgroups through a multivalent, cooperative mechanism, and suggest that the actin filament disassembly activity of ADF/cofilin can be accurately regulated by small changes in the PI(4,5)P2 density at cellular membranes.

Introduction

The actin cytoskeleton underlies multiple cell biological processes, such as motility, cytokinesis, endocytosis, phagocytosis, and intracellular signal transduction. Many human diseases, including cancer and neuronal and cardiovascular diseases, exhibit abnormalities in actin-dependent processes such as cell division and adhesion, as well as in the motile and invasive properties of a cell (1,2). The structure and dynamics of the actin cytoskeleton are regulated both spatially and temporally by a wide array of actin-binding proteins (3,4). ADF/cofilins are among the most central proteins that promote actin dynamics during cell motility (5,6), cytokinesis (7), and endocytosis (8). These small (molecular mass = 15–20 kDa) proteins are present in all eukaryotes and they bind both filamentous and monomeric actin with high affinity, with a preference for ADP-actin (9–11). ADF/cofilins alter the conformation of actin filaments (12) and increase actin dynamics by accelerating the dissociation of actin monomers from the filament pointed end (13) and by severing actin filaments (14). In addition, ADF/cofilins accelerate the dissociation of phosphate from ADP-Pi filaments and promote the debranching of the Arp2/3-nucleated actin filament network (15,16).

The activities of ADF/cofilins are tightly regulated by phosphorylation, acidity, and interactions with other proteins and phosphoinositides (17). Phosphoinositides are multifunctional lipids that modulate many cellular events, such as membrane traffic, intracellular signaling, cytoskeleton organization, and apoptosis (18,19). ADF/cofilins bind PI(4,5)P2, PI(3,4)P2, and PI(3,4,5)P3 with relatively high affinity, but they do not interact with IP3, the inositol headgroup of PI(4,5)P2 (20,21). The actin-binding and F-actin disassembly activities of ADF/cofilins are efficiently inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 both in vitro and in cells (20,22,23). The PI(4,5)P2-binding of ADF/cofilins has also been reported to be sensitive to pH (24).

Despite extensive studies, the molecular mechanism of the PI(4,5)P2-interaction by ADF/cofilins has remained controversial (21,24–28). Two peptides corresponding to residues D9-T25 and P26-V36 at the N-terminus of chick cofilin were shown to decrease the ability of PI(4,5)P2 to abrogate cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction, suggesting that these peptides bind PI(4,5)P2 (28). Mutagenesis studies on budding yeast and Acanthamoeba ADF/cofilins indicated that several different regions of the protein interact with phosphoinositides (21,25). However, in marked contrast to those works, a recent NMR study of vertebrate cofilin suggested that the protein binds PI(4,5)P2 through a specific binding pocket and may also interact with the acyl chains of the lipids (27). Thus, further studies were necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanism of ADF/cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction and to reveal whether different ADF/cofilins bind phosphoinositides through conserved or distinct mechanisms. In addition, the mechanism by which ADF/cofilins can sense relatively small changes in PI(4,5)P2 concentration at the plasma membrane in cells, and why these proteins do not interact with IP3, remained unknown.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Acrylamide was obtained from Sigma, and 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH) was obtained from Invitrogen. Bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 was purchased from Echelon (Salt Lake City, Utah). 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylethanolamine (POPE), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylserine (POPS), 1-palmitoyl-2-(6,7-dibromo-stearoyl) phosphatidylcholine ((6,7)-Br2- PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(9,10-dibromostearoyl) phosphatidyl-choline ((9,10)-Br2-PC), 1-palmitoyl-2-(11,12-dibromostearoyl) phosphatidylcholine ((11,12)-Br2-PC), and L-a-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Pyrenyl-actin was obtained from Cytoskeleton Inc. (Denver, CO).

Protein purification

Wild-type and mutant mouse cofilin-1 were expressed as glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-fusion proteins and were enriched using glutathione agarose beads as described previously (29). GST was cleaved with thrombin (10 U/mL), and cofilins were purified with a Superdex-75 gel filtration column (Pharmacia Biotech).

Circular dichroism measurements

Ultraviolet circular dichroism spectra from 250 to 190 nm were recorded with a JASCO J-810 instrument. The spectra were measured using a 0.1-cm path length quartz cell. The cofilin-1 concentration was 10 μM in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. The data are presented as the averages of five scans.

Vesicle cosedimentation assay

Lipids in desired concentrations were mixed and then dried under a stream of nitrogen, and the lipid residue was subsequently maintained under reduced pressure for at least 4 h. The dry lipids were then hydrated in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl to obtain multilamellar vesicles. To obtain unilamellar vesicles, vesicles were extruded through a polycarbonate filter (100-nm pore size) using a mini extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). Proteins and liposomes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged at 100,000 rpm with a Beckman rotor (TLA 100) for 1 h. The final concentrations of cofilin and liposomes were 2 μM and 500 μM, respectively, in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5 buffer (with or without 100 mM NaCl). Equal proportions of supernatants and pellets were loaded for sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and after electrophoresis the gels were stained with Coomassie Blue. The intensities of the cofilin bands were quantified with the use of the Quantity One program (Bio-Rad).

F-actin binding assays

Pyrene-labeled actin (20 μM) was polymerized for 30 min in F-buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, and 100 mM KCl). After polymerization the actin filments were diluted at 1 μM in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, for fluorescence measurements. Liposomes with different PI(4,5)P2-densities (buffer alone was used as control) were incubated with cofilin for 10 min before they were added to the actin filament solution. The excitation and emission wavelengths for pyrene were 365 and 406 nm, respectively. Both the excitation and emission bandwidths were set at 10 nm. An F-actin cosedimentation assay was carried out using rabbit muscle actin as described previously (21).

Fluorescence spectroscopy experiments

All fluorescence measurements were performed in quartz cuvettes (3-mm path length) with a Perkin-Elmer LS 55 spectrometer. Emission and excitation band passes were set at 10 nm. Fluorescence anisotropy for DPH was measured with excitation at 360 nm and emission at 450 nm. Tryptophan (Trp) fluorescence was excited at 290 nm, and the emission spectra were recorded by averaging five spectra from 310 to 420 nm upon addition of different concentrations of liposomes. Spectra were corrected for the contribution of light scattering in the presence of vesicles. Bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 fluorescence was excited at 547 nm and the emission spectra were recorded from 555 to 600 nm in the presence of different concentrations of cofilin-1. Data were analyzed as described by Ward (30). The apparent dissociation constant, Kd, was calculated by the following equation:

where ΔF is the fluorescence quenching at a given PIP2 concentration, ΔFmax is the total fluorescence quenching of cofilin-1 saturated with PIP2, and [PIP2]T is the total accessible concentration of PIP2. ΔFmax is estimated by curve-fitting the binding data using the Hyperbol.fit program in Microcal Origin. The stoichiometry of binding, p, was derived according to Stinson and Holbrook (31).

For the acrylamide quenching assay, Trp was excited at 295 nm and the data were analyzed according to the Stern-Volmer equation (32), F0/F = 1 + Ksv[Q], where F0 and F represent the fluorescence intensities in the absence and the presence of the quencher (Q), respectively, and Ksv is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant, which is a measure of the accessibility of Trp to acrylamide. Collisional quenching of Trp by brominated phospholipids (Br2-PCs) was introduced to assess the localization of this residue in the bilayer (33).

Results

Binding of cofilin to membranes is dependent on the PI(4,5)P2-density

Cofilin-1 is the most abundant and ubiquitously expressed ADF/cofilin in mammals, and the corresponding isoform has been widely used to investigate interactions between ADF/cofilins and PI(4,5)P2 (23,27). In this work, vesicle cosedimentation and fluorometric assays were applied to assess the binding of mouse cofilin-1 to lipid membranes. The only Trp of mouse cofilin-1 (Trp-104) locates at the hydrophobic core of the protein (34). Our data show that upon PI(4,5)P2-binding, this residue is exposed to a more hydrophilic environment, which causes its fluorescence emission to decrease (Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material). Quenching of Trp fluorescence thus provides a tool for examining the cofilin-1-PI(4,5)P2 interaction by a fluorometric method. Both vesicle cosedimentation and Trp fluorescence assays showed weak binding of cofilin-1 to vesicles containing only PC/PE/PS (60:20:20). However, in the presence of PI(4,5)P2, the binding of cofilin-1 to membranes was significantly enhanced (Fig. 1, A and B). The affinity (Kd) of cofilin for 10% PI(4,5)P2 in the membrane was ∼4 μM, as calculated from Trp fluorescence assay (see Fig. 3 A).

Figure 1.

Cofilin-1 is a PI(4,5)P2-density sensor. (A) A vesicle cosedimentation assay shows that the binding of cofilin-1 to membranes is dependent on the PI(4,5)P2 density. The sigmoidal binding isotherm demonstrates that cofilin-1 binds PI(4,5)P2 cooperatively when the density of PI(4,5)P2 in the membrane is augmented. POPE and POPS were included at 20%. PIP2 was included at 0%, 2%, 4%, 6%, 8%, 10%, and 20%, and the POPC concentration was varied accordingly. For 0% PIP2, vesicles composed of POPC/POPE/POPS (6:2:2) were used. The final concentrations of cofilin-1 and liposomes were 2 μM and 500 μM, respectively, in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5 buffer. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate measurements, with the error bars indicating ±SD. (B) Membrane binding of cofilin-1 was also examined by quenching of Trp fluorescence. The percentage of quenching shows a sigmoidal PI(4,5)P2-binding isotherm, revealing that cofilin-1 binds PI(4,5)P2 cooperatively and that the interaction is dependent on PI(4,5)P2 density. The cofilin-1 concentration was 1 μM in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, and total lipid concentration was 140 μM. Lipid composition was as described in panel A. (C) PI(4,5)P2 inhibits the binding of cofilin-1 to actin filaments, and inhibition is PI(4,5)P2-density dependent. Pyrene-labeled actin (20 μM) was polymerized for 30 min in F-buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, and 100 mM KCl). The actin filaments were diluted to 1 μM in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, for fluorescence measurements. Liposomes with different PI(4,5)P2 densities (buffer alone was used as control) were incubated with cofilin-1 for 10 min before addition of the actin filament solution. Pyrene fluorescence was quenched upon cofilin-1 binding to actin filaments. PI(4,5)P2 containing lipsomes inhibited the binding of cofilin-1 to actin filaments, as detected by the decreased quenching of pyrene fluorescence. The final cofilin-1 concentration in the assay was 0.2 μM.

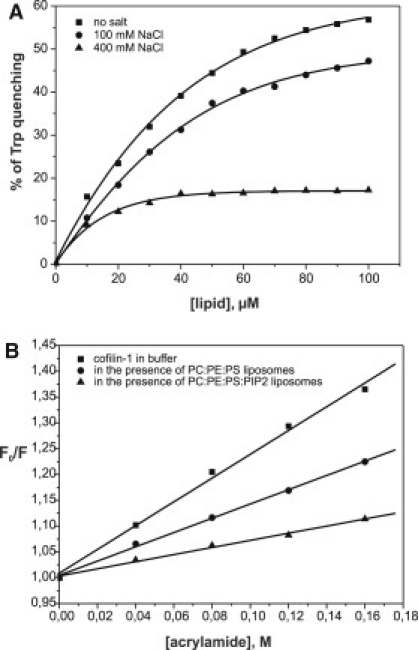

Figure 3.

Trp fluorescence assay shows that cofilin-1 binds PI(4,5)P2, and salt inhibits the interaction. (A) PI(4,5)P2 binding quenches the Trp fluorescence of cofilin-1, suggesting that the environment of Trp-104 is altered due to the binding. Salt inhibits the cofilin-1-PI(4,5)P2 interaction, as detected by the decreased quenching of Trp fluorescence. The final concentration of cofilin-1 in this assay was 1 μM and the lipid composition was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2 (5:2:2:1). (B) Stern-Volmer plots for the quenching of cofilin-1 Trp fluorescence by acrylamide in buffer and in the presence of liposomes. Quenching of Trp fluorescence by acrylamide was diminished in the presence of liposomes, indicating that Trp-104 is protected by lipid binding. The final concentrations of cofilin-1 and liposomes were 1 μM and 140 μM, respectively, in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5.

Cosedimentation and fluorometric assays carried out using vesicles with different PI(4,5)P2 densities (0–20%) revealed that cofilin binding is sensitive to the spatial PI(4,5)P2 density in the membrane (Fig. 1, A and B). The PI(4,5)P2 density-dependent binding curve showed a typical sigmoidal shape indicative of cooperative binding. The half-maximal binding in both vesicle cosedimentation and fluorometric binding assays was observed at ∼6% PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 1, A and B). Of note, the F-actin binding activity of cofilin-1, as detected by steady-state quenching of pyrenyl-actin fluorescence by cofilin-1, also displayed a similar dependence on PI(4,5)P2 density (Fig. 1 C). The inhibition curve was sigmoidal, showing a sharp threshold between 4% and 9% PI(4,5)P2. Thus, interaction of cofilin-1 with membranes and inhibition of its F-actin binding activity are dependent on the spatial PI(4,5)P2 density in the membrane.

Cofilin clusters PI(4,5)P2 molecules at the membrane surface

Because the interaction of cofilin with membranes is dependent on the PI(4,5)P2 density, we next investigated whether cofilin could simultaneously bind multiple PI(4,5)P2 molecules in the membrane. For this purpose, PI(4,5)P2 labeled with bodipy-TMR at the sn-1 position of the acyl chains was applied for a fluorometric PI(4,5)P2-clustering assay. This fluorescent probe has highly superimposable absorption and emission spectra, and exhibits self-quenching properties when two or more molecules are brought together in close proximity. We experimentally tested whether cofilin-1 could induce self-quenching of bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 when the fluorescent lipid was incorporated into the vesicles at a concentration below the level at which self-quenching occurs without proteins (35). Of importance, strong quenching of bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 fluorescence was detected upon cofilin binding, indicating an increased proximity of neighboring bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 molecules sequestered by cofilin-1 (Fig. 2 A). The degree of bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 fluorescence quenching was similar to that previously reported for I-BAR domains, which are efficient PI(4,5)P2-clustering molecules (36). The stoichiometry of the binding derived from the graph indicates that ∼2,6 PI(4,5)P2 molecules are bound per one cofilin molecule. Therefore, this assay demonstrates that cofilin simultaneously binds multiple PI(4,5)P2 molecules and induces their clustering in the membrane.

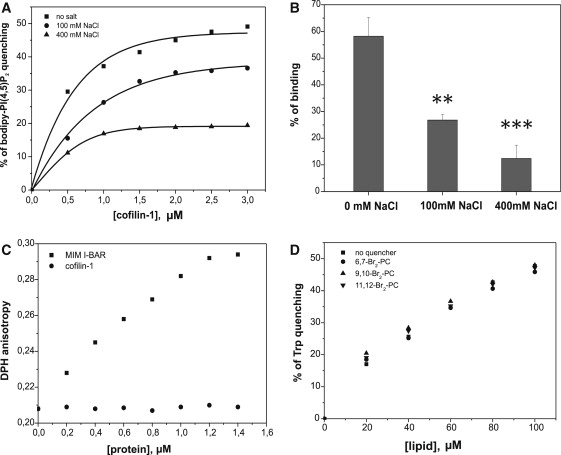

Figure 2.

Cofilin simultaneously binds multiple PI(4,5)P2 molecules on the membrane surface and does not insert into the lipid bilayer. (A) Quenching of bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 demonstrates that cofilin-1 sequesters PI(4,5)P2 on the membrane, and this activity is salt-sensitive. The lipid composition in this assay was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2/bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 (50:20:20:9.5:0.5) and the total lipid concentration was 40 μM. Salt inhibits PI(4,5)P2 clustering by cofilin-1, suggesting electrostatic interactions between cofilin-1 and PI(4,5)P2. (B) A vesicle cosedimentation assay reveals that the cofilin-1-PI(4,5)P2 interaction is inhibited in the presence of high salt, indicative of electrostatic interactions between cofilin-1 and PI(4,5)P2. The assay was carried out under the same conditions (excluding the variation in the salt concentration) as in Fig. 1A. Each data point represents the mean of three independent assays, with the error bars indicating ±SD. A t-test was used to analyze p-values (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0.01). (C) Cofilin-1 does not display detectable effects on DPH anisotropy, suggesting that cofilin-1 does not insert into the lipid bilayer upon membrane binding. The I-BAR domain of missing-in-metastasis protein (36) was used as a positive control in this assay. The lipid composition in the assay was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2 (5:2:2:1, DPH is incorporated into liposomes at a molar ratio of 1:500) and the total lipid concentration was 40 μM. The assay was carried out in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. (D) Trp fluorescence of cofilin-1 is not affected by lipids that are brominated at different positions along the acyl chains, indicating that cofilin-1 does not interact with the acyl chains of the lipids. The lipid composition in this assay was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2/brominated phosphatidylcholine (2:2:2:1:3). The cofilin-1 concentration was 1 μM.

Cofilin-1 interacts with PI(4,5)P2 through electrostatic interactions and does not insert into the lipid bilayer

When the PI(4,5)P2-clustering assay was carried out at different NaCl concentrations, we noticed that the lateral sequestration of PI(4,5)P2 decreased as the salt concentration was increased (Fig. 2 A). We further examined the salt sensitivity of the cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction by vesicle cosedimentation and fluorometric binding assays. The results revealed that the cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction is indeed salt-sensitive (Figs. 2, A and B, and 3 A). These data indicate that the interaction between cofilin and PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes is mediated by electrostatic interactions.

However, a previous study suggested that cofilin may penetrate into the lipid bilayer upon PI(4,5)P2 binding (27). To examine whether cofilin-1 is capable of inserting into the membrane bilayer, we monitored the steady-state fluorescence anisotropy of a membrane probe, DPH. DPH locates at the hydrophobic core of a lipid bilayer without affecting the physical properties of the membranes. It can thus be applied to monitor changes in the rotational diffusion of acyl chains in the membrane interior (37). In contrast to the I-BAR domain of missing-in-metastasis protein, which inserts into the lipid bilayer (36), cofilin-1 did not induce detectable changes in the DPH anisotropy (Fig. 2 C). We further investigated membrane insertion of cofilin-1 by quenching Trp fluorescence using lipids that are brominated at different positions along the lipid acyl chains and can thus be used to estimate the depth of Trp insertion into the bilayer (36). Consistent with the DPH anisotropy data, no further fluorescence quenching of Trp-104 was observed by means of the brominated lipids (Fig. 2 D). Together, these data provide evidence that cofilin-1 binds solely PI(4,5)P2 headgroups at the membrane surface without inserting into the hydrophobic core of the lipid bilayer.

The microenvironment of Trp-104 of cofilin-1 became more hydrophilic upon PI(4,5)P2 binding because its fluorescence was significantly quenched (Fig. 3 A). We further examined the change in the microenvironment of Trp-104 due to PI(4,5)P2 binding by performing assays with an aqueous quencher acrylamide. Collisional quenching of Trp fluorescence by acrylamide provides information concerning the accessibility of Trp to this quencher (38). Maximum quenching occurs when Trp is freely accessible to the quencher. However, when Trp is protected by ligand binding, fluorescence quenching by acrylamide is expected to decrease. The Trp fluorescence intensity was quenched by acrylamide in a concentration-dependent manner in the absence and presence of liposomes (Fig. 3 B). Of interest, the value for Ksv was significantly smaller in the presence of liposomes (Ksv = 0.69 vs. Ksv = 2.3 in the absence of liposomes), suggesting that Trp-104 was protected by membrane binding and became less accessible to the aqueous quencher. Together, these data suggest that Trp-104 is located at the bilayer interface close to the polar PI(4,5)P2 headgroups when cofilin-1 binds to PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes.

Identification of the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of cofilin-1

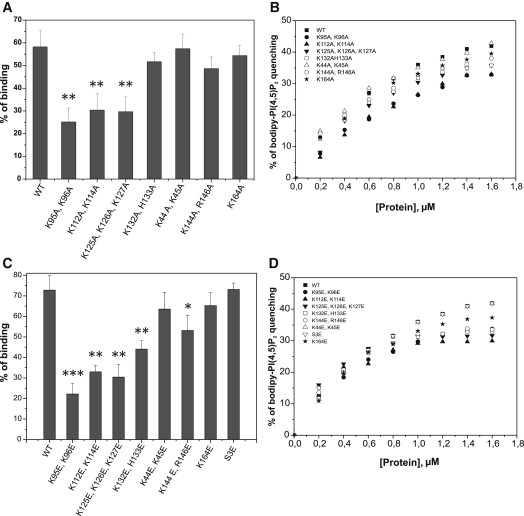

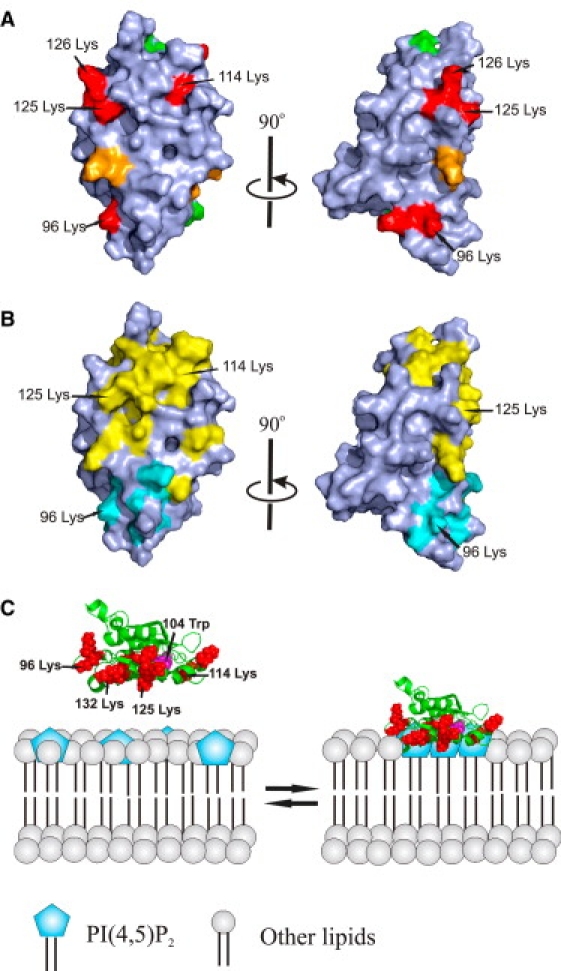

Several techniques, including NMR and native gel electrophoresis, have been applied to map the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of ADF/cofilins. However, both methods have technical limitations, which may explain the discrepancies in the results. The NMR chemical shift experiments were carried out with water-soluble di-C8 forms of PI(4,5)P2, whereas the native gel electrophoresis assays were performed under nonphysiological ionic conditions (21,27). To unambiguously identify the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of ADF/cofilins, we carried out a systematic mutagenesis of mouse cofilin-1 combined with cosedimentation and fluorometric PI(4,5)P2-clustering assays. Because our analysis demonstrated that the interaction between cofilin-1 and PI(4,5)P2 is mainly electrostatic, we mutated nine positively charged clusters of mouse cofilin-1 to alanines and glutamates, and all of the mutants were properly folded (Fig. 4 and Fig. S2). The data revealed that the positively charged clusters K95, K96; K112, K114; and K125, K126, K127 of cofilin-1 are most critical for PI(4,5)P2-binding (Fig. 5, A and C), because substituting these residues with either alanines or glutamates resulted in statistically significant defects in the vesicle cosedimentation assay (Fig. 5, A and C). In addition, residues K132, H133 and K144, R146 appear also to be located at the binding interface, because substitution of these residues by glutamates significantly reduced binding to PI(4,5)P2-rich vesicles (Fig. 5 C). However, substitution of K132, H133 and K144, R146 clusters by alanines resulted in only small defects in the vesicle cosedimentation assay, and these were not statistically significant. This suggests that K132, H133 and K144, R146 make only a minor contribution to PI(4,5)P2 binding (Fig. 5 A). Of importance, the bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 quenching assay demonstrated that the same residues that have a central role in PIP2 binding also play an important role in PI(4,5)P2 clustering (Fig. 5, B and D). Together, these data show that the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of mouse cofilin-1 is a large, positively charged surface located on one face of the molecule (Fig. 6 A).

Figure 4.

Multiple sequence alignment of selected ADF/cofilins. The residues mutated in mouse cofilin-1 in this study are indicated by lines above the sequences. The mutated residues that displayed severe (red) or moderate (yellow) defects in the PI(4,5)P2-binding assays are highlighted. The conserved Trp, Trp-104, is also highlighted (black).

Figure 5.

Determination of the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of cofilin-1. (A) Vesicle cosedimentation assay for examining the effects of various cofilin-1 mutants (alanine substitution) on its PI(4,5)P2-binding activity. This assay suggests that the positively charged clusters K95, K96; K112, K114; and K125, K126, K127 play important roles in PI(4,5)P2 binding by cofilin-1. The assay was carried out under the same conditions described in Fig. 1A. Each data point represents the mean value of three measurements, with the error bars indicating ±SD. A t-test was applied to analyze p-values (∗∗p < 0.01). (B) A bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 quenching experiment to examine the effects of various cofilin-1 mutants (alanine substitution) for PI(4,5)P2 clustering. This assay revealed the importance of the three positively charged clusters (K95, K96; K112, K114; and K125, K126, K127) in PI(4,5)P2 interactions with cofilin-1. The lipid composition in the assay was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2 (5:2:2:1) and the total lipid concentration was 40 μM. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate measurements. (C) The vesicle cosedimentation assay with cofilin-1 mutants (glutamate substitution) suggests that K95, K96; K112, K114; and K125, K126, K127 are the most critical residues in PI(4,5)P2 binding. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate measurements, with the error bars indicating ±SD. A t-test was applied to analyze p-values (∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗p < 0,01, ∗p < 0,05). (D) In similarity to the vesicle cosedimentation assay, the bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 quenching experiment with cofilin-1 mutants (glutamate substitution) also revealed the importance of the same positively charged clusters (K95, K96; K112, K114; and K125, K126K, 127) on PI(4,5)P2 binding. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate measurements.

Figure 6.

A schematic model for the interaction of cofilin with PI(4,5)P2-containing membranes. (A) Space-filling model of the molecular surface of human cofilin-1. The most critical residues in PI(4,5)P2 binding are colored in red and other positively charged residues contributing to PI(4,5)P2 binding are in orange. The mutated residues that did not display effects on PI(4,5)P2 binding are in green. The view on the right represents a 90° clockwise rotation around the long axis of the protein. (B) G-actin and F-actin binding sites of cofilin. Residues that are critical for ADF/cofilin interactions with G-actin and F-actin are in yellow (21,34,41). Residues that are critical for interaction with F-actin, but not G-actin, are in cyan (42–44). The view on the right represents a 90° clockwise rotation around the long axis of the protein. (C) A schematic model for the interaction of cofilin-1 with PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes. The residues that are critical for PI(4,5)P2 binding are indicated in red and PI(4,5)P2 headgroups are indicated in blue. Trp-104 is indicated in magenta. Cofilin-1 simultaneously binds multiple PI(4,5)P2 headgroups through its large, positively charged interface, and thus induces clustering of PI(4,5)P2 on the membrane.

Modulation of cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction by pH

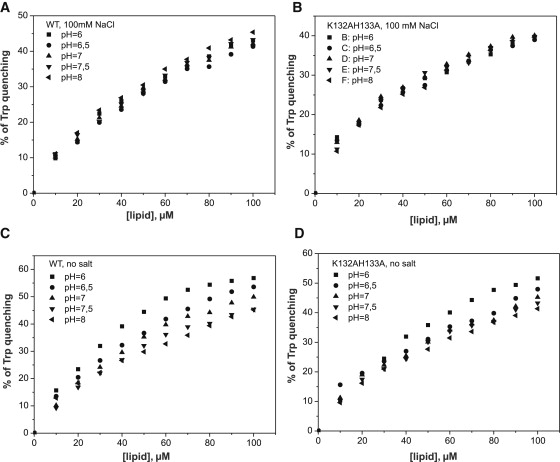

It was recently reported that phosphoinositide binding of ADF/cofilin is pH-sensitive, with diminished binding at a high pH. His-133, which is located at the previously proposed PIP2-binding pocket of cofilin, was shown to play a central role in the pH sensitivity of phosphoinositide binding by cofilin (24). Because our data revealed that ADF/cofilins do not contain a specific phosphoinositide-binding pocket, but instead interact with multiple PI(4,5)P2 headgroups through a large, positively charged interface (see above), we reexamined the pH dependency of phosphoinositide binding by ADF/cofilins. Both the Trp fluorescence and vesicle cosedimentation assays revealed that at physiological ionic conditions, PI(4,5)P2 binding of wild-type cofilin or a cofilin mutant (K132A, H133A) were not affected by changes in the pH (Fig. 7, A and B, and Fig. S3). However, in the absence of NaCl, PI(4,5)P2 binding was pH-sensitive for wild-type cofilin and to a somewhat lesser extent for the K132A, H133A mutant (Fig. 7, C and D). Although no pH sensitivity was detected for cofilin binding to PI(4,5)P2 by Trp fluorescence quenching or vesicle cosedimentation assays at physiological salt, the PI(4,5)P2-clustering activity of wild-type cofilin displayed a clear defect at elevated pH (Fig. 8 A). At identical conditions, the K132A, H133A mutant showed no pH dependency in its ability to cluster PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 8 B), suggesting that His-133 indeed contributes to the pH sensitivity of the PI(4,5)P2-clustering activity of cofilin-1.

Figure 7.

The pH dependency of cofilin-1 binding to PI(4,5)P2. (A and B) PI(4,5)P2 binding quenches the Trp fluorescence of cofilin-1. Based on this assay, the binding of wild-type cofilin-1 (A) and mutant K132A, H133A (B) to PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes is not pH-sensitive under physiological ionic conditions. The final concentration of cofilin-1 in this assay was 1 μM in a total volume of 100 μL of 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. (C and D) PI(4,5)P2 binding of wild-type cofilin-1 (C) is sensitive to changes in pH in the absence of NaCl. However, the binding of mutant K132A, H133A to PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes was less sensitive to changes in pH in the absence of NaCl (D). The final concentration of cofilin-1 was 1 μM in a total volume of 100 μL of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5. In both assays the lipid composition was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2 (5:2:2:1).

Figure 8.

The pH dependency of PI(4,5)P2 clustering by cofilin-1. (A and B) The bodipy-TMR-PI(4,5)P2 quenching assay reveals that PI(4,5)P2 clustering by wild-type cofilin-1 (A) displays moderate pH sensitivity, whereas the K132A, H133A mutant (B) shows no detectable pH sensitivity at physiological ion strength. The final concentration of liposomes was 40 μM in a total reaction volume of 100 μL in 20 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5. The lipid composition was POPC/POPE/POPS/PIP2/Bodipy-TMR-PIP2 (50:20:20:9.5:0.5). The K132A, H133A mutant showed no pH dependency in its ability to cluster PI(4,5)P2, suggesting that His-133 indeed contributes to the pH sensitivity of the PI(4,5)P2-clustering activity of cofilin-1.

Discussion

By applying a combination of biochemical, biophysical, and mutagenesis methods, we were able to reveal several new important aspects concerning the mechanism by which ADF/cofilin family proteins bind to and are regulated by phosphoinositides. We found that 1), ADF/cofilins simultaneously bind multiple PI(4,5)P2 headgroups in a cooperative manner; 2), ADF/cofilins act as sensors of spatial PI(4,5)P2 density at the membrane; 3), ADF/cofilins do not interact with the acyl chains of lipids or insert into the membrane bilayer; 4), ADF/cofilins do not contain a specific phosphoinositide-binding pocket, but instead interact with PI(4,5)P2 headgroups by unspecific electrostatic interactions through a large, positively charged interface of the protein; and 5), PI(4,5)P2-clustering activity of ADF/cofilins is diminished at elevated pH.

Our work reveals a large, positively charged interface of cofilin that simultaneously interacts with multiple PI(4,5)P2 headgroups, and thus provides an explanation for earlier studies demonstrating that ADF/cofilins do not bind IP3 with detectable affinity (20,21). Because cofilin binding to membranes displays a sharp sensitivity to PI(4,5)P2 density, cofilin is not expected to bind soluble IP3 molecules that are not aligned into lateral clusters. Of importance, as previously proposed for N-WASP (39), ADF/cofilins can function as PI(4,5)P2-density sensors at the plasma membrane. Thus, our work provides a biochemical explanation for the results of previous cell biology studies in which a relatively small decrease in the plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 concentration upon EGF stimulation efficiently activated ADF/cofilin in carcinoma cells (22). It is also important to note that the binding threshold of cofilin occurs at 3–8% PI(4,5)P2, which is similar to that reported recently for N-WASP and close to the estimated physiological PI(4,5)P2 density at the plasma membrane (39,40). Thus, ADF/cofilins bind PI(4,5)P2 headgroups in a multivalent manner and sense the density of phosphoinositides at the plasma membrane. Therefore, the F-actin disassembly activity of ADF/cofilins can be efficiently regulated by small changes in the PI(4,5)P2 concentration or spatial distribution of PI(4,5)P2 at the plasma membrane.

Our mutagenesis studies demonstrate that the PI(4,5)P2-binding site of cofilin-1 overlaps extensively with both G-actin and F-actin binding sites of ADF/cofilin (17,41) (see also Fig. S4), which explains why the actin-binding activities of ADF/cofilins are inhibited by PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 6). However, in contrast to the previous NMR study performed with water-soluble di-C8 forms of PI(4,5)P2 (27), our work revealed no specific PI(4,5)P2-binding pocket(s) in cofilin-1. Although neutralization of the three positively charged clusters significantly decreased the PI(4,5)P2-binding and -clustering affinities of cofilin-1, none of the mutants completely abolished PI(4,5)P2 binding. The lack of specific phosphoinositide-binding pocket in ADF/cofilins also explains the lack of phosphoinositide specificity in this family of actin-binding proteins. It is important to note that the PI(4,5)P2-binding residues identified here for mouse cofilin-1 are relatively well conserved in all eukaryotic ADF/cofilins, and that all ADF/cofilins contain a similar positively charged interface that is also critical for actin binding (Figs. 4 and 6). Furthermore, a similar positively charged interface in yeast cofilin was previously suggested to contribute to phosphoinositide binding (21). Therefore, the PI(4,5)P2-binding mechanism identified here for mouse cofilin-1 likely represents a general PI(4,5)P2-binding mechanism of all ADF/cofilins.

In our Trp fluorescence and vesicle cosedimentation analyses, the cofilin-1 interaction with membranes did not display a detectable pH dependency at physiological salt concentration, although PI(4,5)P2 clustering was inhibited at elevated pH (Figs. 7 and 8, and Fig. S3). Thus, it is possible that the previously reported pH sensitivity of the cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interaction is detectable only at nonphysiological low-salt conditions. It is also important to note that a mutation in the previously identified pH-sensor residue H133 (24) resulted only in relatively small defects in PI(4,5)P2 binding and clustering. Thus, H133 and its neighboring residues do not form an important PI(4,5)P2-binding pocket as previously proposed (27). Furthermore, the corresponding histidine is not conserved in invertebrate, plant, or yeast ADF/cofilins. Thus, protonation-deprotonation of H133 is unlikely to have a general role in regulating ADF/cofilin-PI(4,5)P2 interactions in cells.

Taken together, our results show that ADF/cofilins can act as PI(4,5)P2-density sensors that bind and stabilize PI(4,5)P2 clusters at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6 C). Because the large, positively charged phosphoinositide-binding site overlaps with the G-actin/F-actin binding sites of ADF/cofilins, the activity of these proteins is inhibited at PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes. Thus, a relatively small increase in PI(4,5)P2 density at the plasma membrane can significantly inhibit ADF/cofilin-induced filament severing and depolymerization. Furthermore, an increase in PI(4,5)P2 density will lead to the activation of N-WASP-Arp2/3-promoted actin filament assembly (39). These biochemical results are in agreement with recent findings that an increase in PI(4,5)P2 concentration at the plasma membrane promotes actin filament assembly in mammalian cells (45,46). It is important to note that the binding of ADF/cofilins to PI(4,5)P2-rich membranes appears to be transient, and their dissociation from the membranes can be further facilitated by PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis (22,23). Therefore, unspecific, multivalent electrostatic interactions of ADF/cofilins with phosphoinositide-rich membranes appear to be ideally suited for down-regulating the activity of this protein.

Supporting Material

Four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(10)00211-0.

Supporting Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Vartiainen, Juha Saarikangas, and Elena Kremneva for critical readings of the manuscript. Anna-Liisa Nyfors, and Riitta Kivikari (Department of Applied Chemistry and Microbiology, University of Helsinki) are acknowledged for providing technical assistance and access to facilities, respectively.

This study was supported by grants from the Academy of Finland (to H.Z. and P.L.), and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation and Biocentrum Helsinki (to P.L.).

References

- 1.Bamburg J.R., Wiggan O.P. ADF/cofilin and actin dynamics in disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:598–605. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedl P., Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollard T.D. The cytoskeleton, cellular motility and the reductionist agenda. Nature. 2003;422:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nature01598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paavilainen V.O., Bertling E., Lappalainen P. Regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics by actin-monomer-binding proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zebda N., Bernard O., Condeelis J.S. Phosphorylation of ADF/cofilin abolishes EGF-induced actin nucleation at the leading edge and subsequent lamellipod extension. J. Cell Biol. 2000;151:1119–1128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.5.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiuchi T., Ohashi K., Mizuno K. Cofilin promotes stimulus-induced lamellipodium formation by generating an abundant supply of actin monomers. J. Cell Biol. 2007;177:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe H., Obinata T., Bamburg J.R. Xenopus laevis actin-depolymerizing factor/cofilin: a phosphorylation-regulated protein essential for development. J. Cell Biol. 1996;132:871–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lappalainen P., Drubin D.G. Cofilin promotes rapid actin filament turnover in vivo. Nature. 1997;388:78–82. doi: 10.1038/40418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maciver S.K., Weeds A.G. Actophorin preferentially binds monomeric ADP-actin over ATP-bound actin: consequences for cell locomotion. FEBS Lett. 1994;347:251–256. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00552-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlier M.F., Pantaloni D. Control of actin dynamics in cell motility. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;269:459–467. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchoin L., Pollard T.D. Mechanism of interaction of Acanthamoeba actophorin (ADF/cofilin) with actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:15538–15546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galkin V.E., Orlova A., Egelman E.H. ADF/cofilin use an intrinsic mode of F-actin instability to disrupt actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:1057–1066. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlier M.F., Laurent V., Pantaloni D. Actin depolymerizing factor (ADF/cofilin) enhances the rate of filament turnover: implication in actin-based motility. J. Cell Biol. 1997;136:1307–1322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.6.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrianantoandro E., Pollard T.D. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanchoin L., Pollard T.D., Mullins R.D. Interactions of ADF/cofilin, Arp2/3 complex, capping protein and profilin in remodeling of branched actin filament networks. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00749-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan C., Beltzner C.C., Pollard T.D. Cofilin dissociates Arp2/3 complex and branches from actin filaments. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:537–545. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ono S. Mechanism of depolymerization and severing of actin filaments and its significance in cytoskeletal dynamics. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2007;258:1–82. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)58001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niggli V. Regulation of protein activities by phosphoinositide phosphates. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;21:57–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.021704.102317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Paolo G., De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonezawa N., Nishida E., Sakai H. Inhibition of the interactions of cofilin, destrin, and deoxyribonuclease I with actin by phosphoinositides. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:8382–8386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojala P.J., Paavilainen V., Lappalainen P. Identification of yeast cofilin residues specific for actin monomer and PIP2 binding. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15562–15569. doi: 10.1021/bi0117697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Rheenen J., Song X., Condeelis J.S. EGF-induced PIP2 hydrolysis releases and activates cofilin locally in carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 2007;179:1247–1259. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leyman S., Sidani M., Van Troys M. Unbalancing the phosphatidylinositol-(4,5) bisphosphate-cofilin interaction impairs cell steering. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:4509–4523. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frantz C., Barreiro G., Barber D.L. Cofilin is a pH sensor for actin free barbed end formation: role of phosphoinositide binding. J. Cell Biol. 2008;183:865–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Troys M., Dewitte D., Ampe C. The competitive interaction of actin and PIP2 with actophorin is based on overlapping target sites: design of a gain-of-function mutant. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12181–12189. doi: 10.1021/bi000816c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yonezawa N., Homma Y., Nishida E. A short sequence responsible for both phosphoinositide binding and actin binding activities of cofilin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:17218–17221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorbatyuk V.Y., Nosworthy N.J., King G.F. Mapping the phosphoinositide-binding site on chick cofilin explains how PIP2 regulates the cofilin-actin interaction. Mol. Cell. 2006;24:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kusano K., Abe H., Obinata T. Detection of a sequence involved in actin-binding and phosphoinositide-binding in the N-terminal side of cofilin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1999;190:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vartiainen M.K., Mustonen T., Lappalainen P. The three mouse actin-depolymerizing factor/cofilins evolved to fulfill cell-type-specific requirements for actin dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:183–194. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward L.D. Measurement of ligand binding to proteins by fluorescence spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 1985;117:400–414. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)17024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stinson R.A., Holbrook J.J. Equilibrium binding of nicotinamide nucleotides to lactate dehydrogenases. Biochem. J. 1973;131:719–728. doi: 10.1042/bj1310719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eftink M.R., Ghiron C.A. Exposure of tryptophanyl residues in proteins. Quantitative determination by fluorescence quenching studies. Biochemistry. 1976;15:672–680. doi: 10.1021/bi00648a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladokhin A.S. Analysis of protein and peptide penetration into membranes by depth-dependent fluorescence quenching: theoretical considerations. Biophys. J. 1999;76:946–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pope B.J., Zierler-Gould K.M., Ball L.J. Solution structure of human cofilin: actin binding, pH sensitivity, and relationship to actin-depolymerizing factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:4840–4848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blin G., Margeat E., Picart C. Quantitative analysis of the binding of ezrin to large unilamellar vesicles containing phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1021–1033. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saarikangas J., Zhao H., Lappalainen P. Molecular mechanisms of membrane deformation by I-BAR domain proteins. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaritsky A., Parola A.H., Masalha H. Homeoviscous adaptation, growth rate, and morphogenesis in bacteria. Biophys. J. 1985;48:337–339. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83788-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Kroon A.I., Soekarjo M.W., De Kruijff B. The role of charge and hydrophobicity in peptide-lipid interaction: a comparative study based on tryptophan fluorescence measurements combined with the use of aqueous and hydrophobic quenchers. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8229–8240. doi: 10.1021/bi00488a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papayannopoulos V., Co C., Lim W.A. A polybasic motif allows N-WASP to act as a sensor of PIP(2) density. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McLaughlin S., Wang J., Murray D. PIP(2) and proteins: interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2002;31:151–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paavilainen V.O., Oksanen E., Lappalainen P. Structure of the actin-depolymerizing factor homology domain in complex with actin. J. Cell Biol. 2008;182:51–59. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lappalainen P., Fedorov E.V., Drubin D.G. Essential functions and actin-binding surfaces of yeast cofilin revealed by systematic mutagenesis. EMBO J. 1997;16:5520–5530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pope B.J., Gonsior S.M., Weeds A.G. Uncoupling actin filament fragmentation by cofilin from increased subunit turnover. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:649–661. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ono S., McGough A., Weeds A.G. The C-terminal tail of UNC-60B (actin depolymerizing factor/cofilin) is critical for maintaining its stable association with F-actin and is implicated in the second actin-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5952–5958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozelle A.L., Machesky L.M., Yin H.L. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate induces actin-based movement of raft-enriched vesicles through WASP-Arp2/3. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto M., Hilgemann D.H., Yin H.L. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate induces actin stress-fiber formation and inhibits membrane ruffling in CV1 cells. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:867–876. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.