Abstract

The polycomb repressive complex (PRC) 1 protein Ring1B is an ubiquitin ligase that modifies nucleosomal histone H2A, a modification which plays a critical role in regulation of gene expression. We have shown that self-ubiquitination of Ring1B generates multiply branched, “noncanonical” polyubiquitin chains that do not target the ligase for degradation, but rather stimulate its activity toward histone H2A. This finding implies that Ring1B is targeted by a heterologous E3. In this study, we identified E6-AP (E6-associated protein) as a ligase that targets Ring1B for “canonical” ubiquitination and subsequent degradation. We further demonstrated that both the self-ubiquitination of Ring1B and its modification by E6-AP target the same lysines, suggesting that the fate of Ring1B is tightly regulated (e.g., activation vs. degradation) by the type of chains and the ligase that catalyzes their formation. As expected, inactivation of E6-AP affects downstream effectors: Ring1B and ubiquitinated H2A levels are increased accompanied by repressed expression of HoxB9, a PRC1 target gene. Consistent with these findings, E6-AP knockout mice display an elevated level of Ring1B and ubiquitinated histone H2A in various tissues, including cerebellar Purkinje neurons, which may have implications to the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by deficiency of E6-AP in the brain.

Keywords: polycomb complexes, ubiquitin-proteasome system

Ubiquitination has been first described as a proteolysis signal, but it has recently become evident that this modification can serve numerous nonproteolytic functions. Substrates are typically modified on internal lysines, but they can also be ubiquitinated on the N-terminal residue or on internal threonine, serine, or cysteine residues. In many cases, the modification is in the form of a polyubiquitin chain where one ubiquitin moiety is linked via its C-terminal glycine residue to one of seven internal lysines in the previously conjugated moiety (K6, 11, 27, 29, 33, 48, and 63). In other cases, monoubiquitination, multiple monoubiquitinations, and modification by a linear ubiquitin chain (where the C-terminal residue is linked to the N-terminal residue of the previously conjugated moiety) have been described (1).

It appears that the type of modification determines the fate of the target protein. In general, targeting of substrates for proteasomal degradation is mediated by K48-based polyubiquitin chains. Other linkages result in different outcomes. For example, K63-based oligo- or polyubiquitin chains are involved in targeting of membrane proteins to the lysosome/vacuole (2) and in activation of NF-κB (3) that appears also to be dependent on linear chains (4).

The diversity of ubiquitination is exemplified by Ring1B, a component of the polycomb group (PcG) repressive complex (PRC) 1. PcG complexes act as epigenetic transcriptional repressors that modify nucleosomal histones, which in turn control embryogenesis, tissue differentiation, stem cell pluripotency, and X chromosome inactivation (5). Ring1B is a RING finger-containing E3 ligase that monoubiquitinates histone H2A (6). This modification is involved in the initiation and maintenance of the silenced state of PcG target genes. Ring1B is also controlled by the ubiquitin system. It was previously shown that it undergoes self-ubiquitination, but in contrast to the accepted notion that self-ubiquitination of RING finger E3s serves as a negative feedback loop, inducing their own degradation, here it serves to activate Ring1B as histone H2A ligase (7). Detailed analysis showed that the self-generated chains formed by Ring1B are based on K6, K27, and K48 of the ubiquitin molecule, and all these lysine residues must be present on the same ubiquitin moiety, suggesting the formation of mixed and multiply branched chains.

The finding that self-ubiquitination of Ring1B does not lead to its degradation, along with observations that its partner Bmi1 stabilizes it, and that it is a short-lived protein degraded by the proteasome following ubiquitination (7), suggested that a ligase exogenous to PRC1 targets it for degradation. Here we identify E6-AP (E6-associated protein) as a Ring1B ubiquitin ligase. We also show that E6-AP modifies the same lysine residues in Ring1B that are modified during self-ubiquitination and activation of the ligase. This dual control by self-ubiquitination and the exogenous ligase probably ensures delicate regulation of PcG-dependent gene expression.

E6-AP is a HECT (homologous to the E6-AP carboxyl terminus) domain-containing E3 that was first described as the ligase that targets p53 for degradation in the presence of the human papillomavirus oncogene E6, a process that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of human uterine cervical carcinoma (8). It was obvious that it must also target proteins in an E6-independent manner. Indeed, several such substrates such as members of the Src family of protein kinases (9) and the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) protein (10) have been described. Defects in the E6-AP gene were found to underlie the pathology of Angelman syndrome, a severe neurodevelopmental pathology characterized by mental retardation and motor disorders. E6-AP is imprinted in different regions of the brain, for example, in cerebellar Purkinje cells and the hippocampus, and its absence in these areas due to defects in the normally expressed allele results in this severe syndrome (11–13). The possible involvement of Ring1B in this pathology was studied in E6-AP-deficient mice where we found increased level of Ring1B in cerebellar Purkinje cells and in other body tissues accompanied by elevated level of ubiquitinated histone H2A.

Results

Identification of E6-AP as an Ubiquitin Ligase of Ring1B.

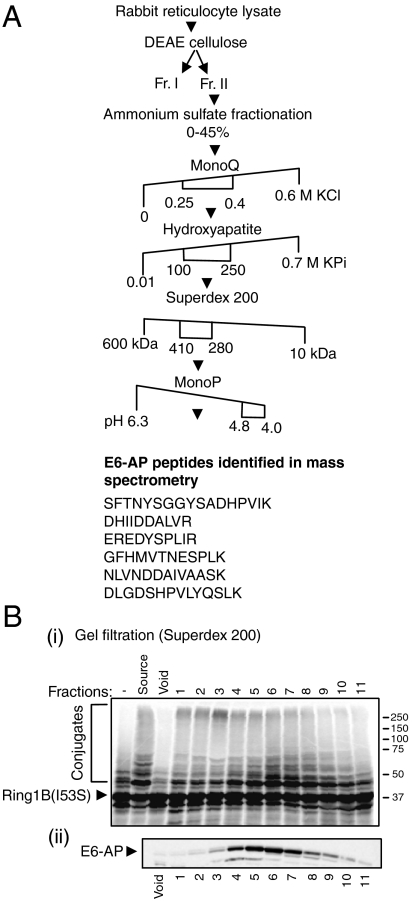

To identify the exogenous ligase that targets Ring1B, we employed successive chromatographical separations of crude reticulocyte extract coupled to reconstituted cell free ubiquitination assays where the resolved fractions were used as a source for the ligase (Fig. 1A). We used a catalytically inactive mutant of Ring1B (I53S) as a substrate to ensure that the conjugates formed are generated solely by the exogenous E3. After the final fractionation step (pH gradient), the active fractions were subjected to mass spectrometrical analysis which identified high abundance of peptides derived from the HECT domain-containing ligase E6-AP (Fig. 1A). The presence of E6-AP in active fractions was corroborated by Western blot analysis of the gel filtration-derived (fractions 4–7), which overlapped with one peak of conjugation of Ring1B (Fig. 1B). It should be noted that an additional, yet unidentified, E3 that conjugates Ring1B has also been resolved (Fig. 1B, mostly in fraction 3).

Fig. 1.

Identification of E6-AP as Ring1B E3 ligase. (A) Chromatographical resolution of the E3 ligase of Ring1B and its identification as E6-AP. Numbers represent salt concentrations (M), molecular weight (kDa), or the pH at which the E3 ligase activity was eluted from the respective column. (B) Activity assay of the fractions resolved by the Superdex 200 gel filtration column. 35S-labeled Ring1BI53S was subjected to in vitro ubiquitination as described under Materials and Methods. The SDS-PAGE-resolved proteins were visualized via PhosphorImaging (i) or following Western blotting using anti-E6-AP antibody (ii).

Ring1B is Ubiquitinated and Degraded by E6-AP in Vitro.

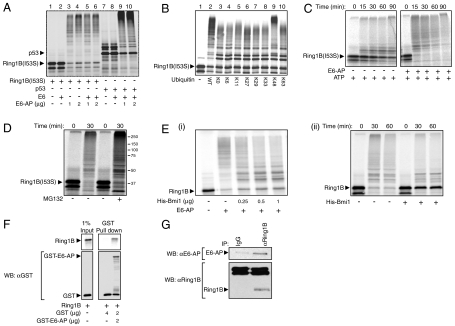

In order to corroborate that E6-AP mediates ubiquitination of Ring1B and to test whether this reaction is stimulated by E6, we subjected Ring1B to ubiquitination in a reconstituted cell free system composed of purified components. As seen in Fig. 2A, Ring1B is ubiquitinated by E6-AP, and in contrast to ubiquitination of p53, this reaction does not require E6.

Fig. 2.

Ring1B is ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation by E6-AP in vitro. (A) In vitro translated and 35S-labeled Ring1BI53S and p53 were ubiquitinated in a cell free reconstituted system in the presence or absence of recombinant E6 and His-E6-AP as indicated. (B) 35S-labeled Ring1BI53S was conjugated in a cell free reconstituted system in the presence of ubiquitin species that contain the indicated lysine residues. (C and D) 35S-labeled Ring1BI53S was subjected to in vitro degradation in the presence of ATP and an ATP-regenerating system, E6-AP, and MG132 (20 μM) as indicated. (E) Ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of Ring1B by E6-AP is inhibited by the addition of Bmi1. 35S-labeled Ring1B was subjected to in vitro ubiquitination (i) and degradation (ii) in the presence of His-E6-AP and His-Bmi1 as indicated. Conjugation and degradation assays were carried out as described under Materials and Methods. The SDS-PAGE resolved proteins were visualized via PhosphorImaging. (F) 35S-labeled WT Ring1B was pulled down by GST or GST-E6-AP using glutathione beads. The SDS-PAGE-resolved proteins were visualized using PhosphorImaging (Ring1B) or following Western blotting (GST). (G) Endogenous Ring1B was immunoprecipitated from U2OS cell extract using a specific antibody. The precipitates were resolved via SDS-PAGE and analyzed for the presence of E6-AP and Ring1B using specific antibodies.

E6-AP catalyzes the formation of K48-based polyubiquitin chains that target the modified substrates to proteasomal degradation (14). This is true also for its substrate Ring1B. As seen in Fig. 2B, only a ubiquitin species that contain lysine in position 48 could promote generation of high molecular mass conjugates of Ring1B (lanes 2 and 9). All other ubiquitin variants behaved similarly to a lysine less ubiquitin (K0), and probably supported multiple monoubiquitinations of Ring1B (lanes 3–8 and 10). As expected, the K48-based polyubiquitination catalyzed by E6-AP led to the degradation of Ring1B (Fig. 2C) that was mediated by the proteasome, as it was inhibited by MG132 (Fig. 2D).

Previously we observed that Bmi1, another component of the PRC1, stabilizes Ring1B, which led us to hypothesize that it protects Ring1B from proteasomal degradation (7). Now we show that both ubiquitination and degradation of Ring1B by E6-AP were inhibited when Bmi1 was present (Fig. 2E).

Next we aimed to demonstrate that E6-AP interacts physically with Ring1B. As seen in Fig. 2F, Ring1B coprecipitates with GST-E6-AP in a cell free system. The same is true for the endogenous proteins in cells, as E6-AP was readily identified in Ring1B precipitates from U2OS cells (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these experiments strongly suggest that E6-AP can target Ring1B for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation.

Lysine Residues That Are Targeted During Self-Ubiquitination Are also Conjugated by E6-AP.

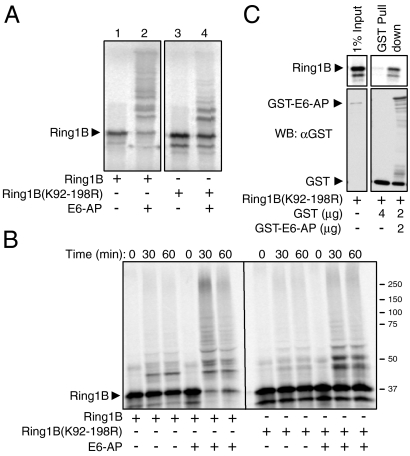

We previously showed that self-ubiquitination of Ring1B that activates the enzyme occurs on a cluster of 10 lysines located between residues 92–198 (7). Because ubiquitination of Ring1B serves two distinct and apparently opposing functions—activation and destruction—it was important to identify the lysine(s) that are involved in destruction. As seen in Fig. 3A, Ring1B(K92–198R) (a mutant in which all the lysines in the cluster were substituted with arginines) was poorly ubiquitinated by E6-AP (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 2 to 4). Not surprisingly, Ring1B(K92–198R) was also stable (Fig. 3B). The failure of E6-AP to ubiquitinate and degrade Ring1B(K92–198R) was not due to the lack of interaction between the two proteins, as they bound one another efficiently (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

The lysine residues in Ring1B that are self-ubiquitinated and are essential for its histone H2A ligase activity are also ubiquitinated by E6-AP. (A and B) In vitro translated and 35S-labeled WT Ring1B or Ring1B(K92-198R) were subjected to ubiquitination (A) or degradation (B) in a cell free reconstituted system in the presence of recombinant His-E6-AP as described under Materials and Methods. (C) 35S-labeled Ring1B(K92-198R) was pulled down by GST or GST-E6-AP as described in the legend to Fig. 2F.

Activating Self-Ubiquitination of Ring1B Prevents Its Targeting by E6-AP, and Ubiquitination by E6-AP Inhibits Ring1B Histone H2A Ligase Activity.

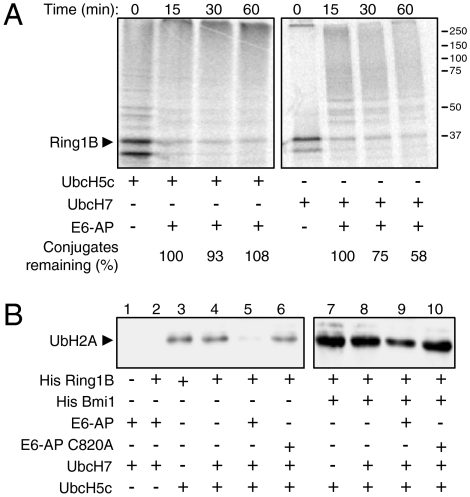

The observation that the same lysine residues that are modified during the activating self-ubiquitination of Ring1B are also targeted by E6-AP for destruction of the protein, led us to hypothesize that these two distinct modes of ubiquitination are interplaying to regulate the abundance and activity of Ring1B. To study the relationship between the two processes, we preincubated labeled Ring1B with UbcH5c (Fig. 4A, Left) or UbcH7 (Right). UbcH5c supports self-ubiquitination of Ring1B but also ubiquitination by E6-AP, whereas UbcH7 supports only E6-AP activity (7). Following the preincubation, E6-AP and crude extract that contains proteasomes were added. As is evident, when Ring1B was allowed to catalyze its own ubiquitination, it was protected from degradation (Fig. 4A, Left). In contrast, when Ring1B was not protected by the self-ubiquitination, the E6-AP generated-chains targeted it to degradation (Fig. 4A, Right). Next, it was important to examine whether the interplay between the two modes of ubiquitination affects also Ring1B function as histone H2A ligase. Toward this end, we subjected purified nucleosomes to ubiquitination by Ring1B, initially (5 min) in the presence of E6-AP and UbcH7. This was followed by the addition of UbcH5c (Fig. 4B). The reaction was carried out in the absence (Fig. 4B, Left) and presence (Fig. 4B, Right) of Bmi1 that is known to increase the activity of Ring1B (7, 15). As the experiment shows, WT E6-AP inhibited significantly the ability of Ring1B to ubiquitinate the histone molecule (Fig. 4B, compare lane 5 to lane 4, and lane 9 to lane 8). The inability of catalytically inactive E6-AP (C820A) to inhibit Ring1B activity (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 6 to 5 and 10 to 9), demonstrates that the inhibition is attributed to the ligase activity of E6-AP.

Fig. 4.

The activating self-ubiquitination of Ring1B protects it from targeting by E6-AP, and E6-AP ubiquitination of Ring1B inhibits its activity as histone H2A ligase. (A) In vitro translated and 35S-labeled Ring1B was preincubated with UbcH5C (can promote both self- and E6-AP-mediated ubiquitination) or UbcH7 (can promote only E6-AP-mediated ubiquitination) in a cell free reconstituted system. Recombinant His-E6-AP and reticulocyte lysate (as a source of proteasomes) were then added for the indicated times. The SDS-PAGE-resolved proteins were visualized via PhosphorImaging. (B) Nucleosomes were subjected to ubiquitination in a cell free reconstituted system in the presence of the indicated bacterially purified proteins as described under Materials and Methods. Monoubiquitinated histone H2A was detected using a specific antiubiquitinated histone H2A antibody.

E6-AP Affects Ring1B Function in Cells Through Regulation of Its Stability.

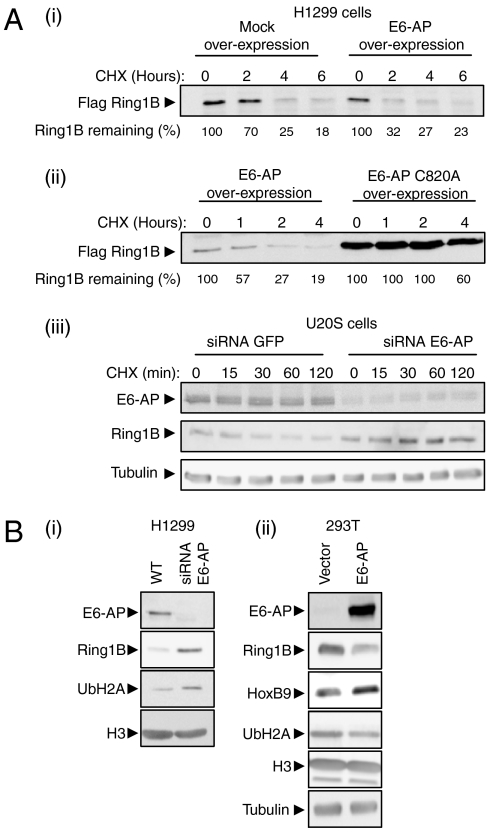

To study the effects of E6-AP on Ring1B in cells, we monitored its abundance and stability following manipulation of E6-AP level. As seen in Fig. 5A (i), overexpression of WT E6-AP in H1299 cells decreases both the abundance and the stability of Ring1B. In contrast, expression of a catalytically inactive E6-AP increases the abundance and stabilizes Ring1B [Fig. 5A (ii)]. Consistent with these results, silencing of E6-AP expression in U2OS cells (siRNA) resulted in stabilization of Ring1B [Fig. 5A (iii)]. As expected, depletion of E6-AP is accompanied by elevation in the steady-state level of ubiquitinated histone H2A, the ligase target of Ring1B [Fig. 5B (i)].

Fig. 5.

E6-AP affects Ring1B downstream targets: ubiquitination of histone H2A and expression of HoxB9. (A, i and ii) Time-dependent stability of Flag-Ring1B expressed along with E6-AP, E6-AP(C820A), or an empty vector, was monitored in H1299 cells following the addition of CHX. (iii) Stability of endogenous Ring1B was monitored in U2OS cells in the presence of siRNA targeting either GFP or E6-AP following the addition of CHX. (B) Endogenous Ring1B steady state level was studied in (i) H1299 cells following depletion of E6-AP, and (ii) 293T cells overexpressing E6-AP. Cell extracts were analyzed (after SDS-PAGE and Western blotting) for ubiquitinated histone H2A, HoxB9, and histone H3 (as loading control) using specific antibodies.

To investigate the downstream effects of E6-AP expression on Ring1B function in cells, we analyzed the level of HoxB9, a downstream target of PcG-mediated gene repression (16). As seen in Fig. 5B (ii), HoxB9 level is increased following E6-AP overexpression. This is most probably due to the degradation of Ring1B and decreased ubiquitination of histone H2A which alleviates the PcG repressive activity. It should be noted that although, most probably, the effect on HoxB9 is transcriptional, direct monitoring of the protein's mRNA did not yield conclusive evidence. Thus, other effects of E6-AP on HoxB9 regulation cannot be ruled out. Taken together, these data implicate E6-AP as a regulator of Ring1B abundance, thereby affecting the expression of genes regulated by PcG complexes.

Analysis of Ring1B and Ubiquitinated Histone H2A in E6-AP Knockout Mice.

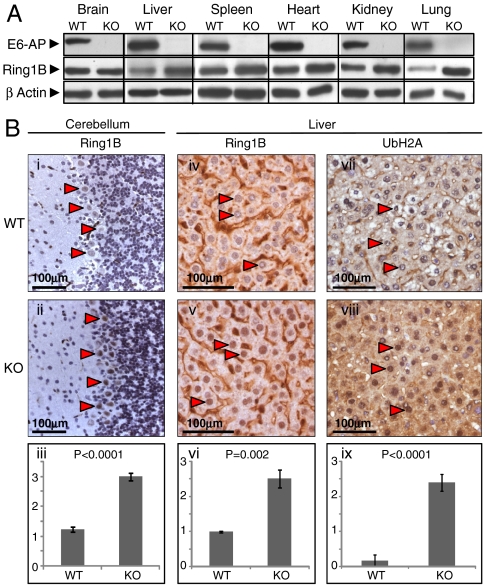

To further investigate the relevance of Ring1B regulation by E6-AP, we followed its expression in various tissues from E6-AP knockout mice. As seen in Fig. 6A, in all tissues tested except for the brain, the steady-state level of Ring1B was elevated in the E6-AP-deficient mice. Because Angelman syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder where E6-AP is missing in specific regions of the brain, among them the cerebellar Purkinje cells and the hippocampus, we decided to further dissect the pattern of Ring1B expression in the brain via immunohistochemical analysis. As clearly seen in Fig. 6B (i and ii), expression of Ring1B was elevated specifically in cerebellar Purkinje cells of E6-AP knockout mice. Not surprisingly, Ring1B was also elevated in the livers of these mice (iv and v). Importantly, ubiquitinated histone H2A was also elevated in the liver (vii and viii), suggesting a direct relationship between the ligase and its substrate.

Fig. 6.

E6-AP knockout mice display elevated Ring1B level in various tissues and cerebellar Purkinje cells. (A) Brain, liver, spleen, heart, kidney, and lung tissues were homogenized in p300 buffer and analyzed following Western blotting for Ring1B expression as described under Materials and Methods. (B) Representative photomicrographs of immunohistochemical staining for Ring1B in the cerebellum (i and ii) and liver (iv and v), and for ubiquitinated histone H2A in the liver (vii and viii) of E6-AP wild type and knockout mice. In all sections, arrows point to representative stained nuclei of cerebellar Purkinje cells (i and ii) or hepatocytes (iv, v, vii, and viii); (iii, vi, and ix) represent semiquantitative assessment of the data presented in panels i and ii, iv and v, and vii and viii, respectively. For these assessments, the intensity of staining was scored by a pathologist that was blinded to the genotype, using an arbitrary scale of 0–3. Two-sided Student’s t test was used to assess statistical significance. Values are average ± SEM.

Discussion

One of the most important, yet unsolved, problems in the rapidly expanding ubiquitin field is how more than 1,500 of its components (∼7% of the entire human genome) are degraded. Particularly interesting is the mechanism of degradation of the ∼800 ligases that constitute the specific substrates recognition elements of the system. The two major groups of these proteins, the RING finger- and the HECT domain-containing E3s can catalyze their own ubiquitination, which was suggested to serve as a mechanism for their autocatalytic destruction (17–19). However, it appears that this is only partially true. Thus, in the cases of Ring1B, Nedd4, and Diap1, for example, the self-ubiquitination serves to regulate the activity of the enzymes (7, 20, 21). These findings imply that these ligases must have “external” ligases that target them for degradation, as has been previously described for gp78 that is targeted by Hrd1 (22, 23), and for the Cbl ligases that are targeted by Nedd4 and Itch (24). In the present study, we identified E6-AP as an ubiquitin ligase that governs the stability of Ring1B. This was demonstrated in a cell free reconstituted system, cells, and E6-AP knockout mice. These observations highlight an as yet unexplored layer of complexity in the hierarchy of the ubiquitin system—how the degradation pathways of its own components are organized. One can conceive a linear hierarchical structure where one ligase controls the other, or a pyramidal structure with master ligases controlling several ligases that reside in lower layers, or a circle where two or more ligases control one another. It should be noted that in both the pyramidal and the linear models, the uppermost ligase(s) should control itself.

The finding that the same cluster of lysines in Ring1B that is subjected to self-ubiquitination is also targeted by E6-AP suggests the formation of different ubiquitin chains in the same region of Ring1B as a mechanism of regulating both the abundance of the enzyme and its activity as a ligase toward histone H2A. Such a mechanism commits Ring1B to a single route at a time; however, how the navigation is regulated is still an enigma.

From our experiments, it became evident that E6-AP is not the only ligase that targets Ring1B (Fig. 1B). This observation may explain the differential abundance of Ring1B in different tissues, and the finding that in a total brain homogenate, unlike in specific brain regions such as in the cerebellar Purkinje cell layer known to be affected in Angelman syndrome (25), Ring1B level was similar in both WT and E6-AP knockout mice (Fig. 6 A and B). The presence of more than one E3 that targets Ring1B and its (their) possible different tissue distribution suggests a complex regulation of Ring1B rather than simple functional redundancy.

As expected, E6-AP deficiency results in an elevated level of ubiquitinated nucleosomal histone H2A (Fig. 6B). This may result in increased global repressive transcriptional activity, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of Angelman syndrome. This hypothesis can be tested experimentally by the generation of tissue-specific Ring1B overexpressing mice. It is expected that, if the hypothesis is correct, the mice will display a phenotype similar to that displayed by the E6-AP knockout mice, however, in the presence of WT E6-AP.

Materials and Methods

Additional methods are described in the SI Text.

Antibodies.

Antibodies to E6-AP (H-182), β actin (C-2), HoxB9 (H-80), histone H3 (C-16), and GST (B-14) were from Santa Cruz. Mouse anti-Flag (M2) and antitubulin (DM1A) were from Sigma. Monoclonal antiubiquitinated histone H2A (E6C5) was from Upstate, and monoclonal anti-Ring1B (3-3) and isotype control IgG2b were from MBL International.

Plasmids and siRNAs.

Ring1B cDNA in pCS2+ for in vitro translation and cell expression, and in pT7-7 for bacterial expression, and Bmi1 cDNA in pT7-7 were described elsewhere (7). Flag-Ring1B for cell expression was cloned into pEBB (26). cDNAs for the different ubiquitin lysine mutants and for 6xHis-E6-AP cloned into pET14b bacterial expression vector were kindly provided by R. Baer (Columbia University, New York). GST-E6-AP was the kind gift of Jon Huibregtse (University of Texas, Austin). cDNA coding for p53 was in pSP64 (Promega). Mutations were introduced using the QuickChange® kit (Stratagene). The validity of all cDNAs was verified by sequencing. siRNA oligonucleotides to target E6-AP were designed as described (27).

Protein Interaction Analyses.

For analysis of endogenous Ring1B-E6-AP complexes, U2OS cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation using the indicated antibodies and immobilized proteins A and G (Roche). The immune complexes were resolved via SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and the component proteins visualized using ECL. For GST pulldown, 2 µg of GST-E6-AP and 35S-labeled Ring1B or Ring1B(K92–198R) (∼60,000 cpm) were pulled down using immobilized glutathione (Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. GST (2 μg) was added to all reactions as a blocking protein to ascertain specificity of binding.

In Vitro Conjugation and Degradation.

In vitro conjugation and degradation assays, and nucleosomes preparation were carried out as described (7). For conjugation of WT Ring1B by E6-AP, we used the UbcH7 E2 that does not promote self-ubiquitination of Ring1B. Ubiquitination of histone H2A by Ring1B in the presence of E6-AP was conducted as follows: Ring1B, E6-AP, nucleosomes, and UbcH7 were preincubated for 5 min in order to allow for ubiquitination of Ring1B by E6-AP. Following the preincubation, UbcH5c was added to promote self-ubiquitination of Ring1B which is necessary for its activation as the histone H2A ligase. For degradation assays, Ring1B was incubated in the presence of a similar system used to monitor conjugation, except that reticulocyte lysate (50 μg) was added as a source of proteasomes, and ATP (0.5 mM) and ATP-regenerating system (phosphocreatine 10 mM, creatine phosphokinase 1 μg) were used instead of ATPγS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. Jon Huibregtse, (University of Texas, Austin) for the bacterial vectors expressing E6-AP, Dr. Richard Baer (Columbia University, New York) for the cDNAs coding for bacterially expressed ubiquitin proteins and His-tagged E6-AP, and Dr. Arthur L. Beaudet (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston) and Dr. Ygal Haupt (Hebrew University, Jerusalem) for the E6-AP knockout mice. We also thank Dr. Aaron Razin (Hebrew University–Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem) for thoughtful advice. This research was generously supported by the Angelman Syndrome Foundation. The research was also supported by grants from the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon Adelson Foundation for Medical Research, the Israel Science Foundation, the German–Israeli Foundation for Research and Scientific Development, the European Union Network of Excellence Rubicon, an Israel Cancer Research Fund USA Professorship, and a grant from the Foundation for Promotion of Research in the Technion.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1003108107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ye Y, Rape M. Building ubiquitin chains: E2 enzymes at work. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:755–764. doi: 10.1038/nrm2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rotin D, Kumar S. Physiological functions of the HECT family of ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:398–409. doi: 10.1038/nrm2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skaug B, Jiang X, Chen ZJ. The role of ubiquitin in NF-κB regulatory pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:769–796. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.102750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tokunaga F, et al. Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-κB activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:123–132. doi: 10.1038/ncb1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon JA, Kingston RE. Mechanisms of polycomb gene silencing: Knowns and unknowns. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:697–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, et al. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. 2004;431:873–878. doi: 10.1038/nature02985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Saadon R, Zaaroor D, Ziv T, Ciechanover A. The polycomb protein Ring1B generates self atypical mixed ubiquitin chains required for its in vitro histone H2A ligase activity. Mol Cell. 2006;24:701–711. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheffner M, Huibregtse JM, Vierstra RD, Howley PM. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oda H, Kumar S, Howley PM. Regulation of the Src family tyrosine kinase Blk through E6-AP-mediated ubiquitination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9557–9562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louria-Hayon I, et al. E6-AP promotes the degradation of the PML tumor suppressor. Cell Death Differ. 2009;10:1156–1166. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albrecht U, et al. Imprinted expression of the murine Angelman syndrome gene, Ube3a, in hippocampal and Purkinje neurons. Nat Genet. 1997;17:75–78. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vu TH, Hoffman AR. Imprinting of the Angelman syndrome gene, UBE3A, is restricted to brain. Nat Genet. 1997;17:12–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rougeulle C, Glatt H, Lalande M. The Angelman syndrome candidate gene, UBE3A/E6-AP, is imprinted in brain. Nat Genet. 1997;17:14–15. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Pickart CM. Different HECT domain ubiquitin ligases employ distinct mechanisms of polyubiquitin chain synthesis. EMBO J. 2005;24:4324–4333. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao R, Tsukada Y, Zhang Y. Role of Bmi-1 and Ring1A in H2A ubiquitylation and Hox gene silencing. Mol Cell. 2005;20:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki M, et al. Involvement of the Polycomb-group gene Ring1B in the specification of the anterior-posterior axis in mice. Development. 2002;129:4171–4183. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryoo HD, Bergmann A, Gonen H, Ciechanover A, Steller H. Regulation of Drosophila IAP1 degradation and apoptosis by reaper and ubcD1. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:432–438. doi: 10.1038/ncb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y, Fang S, Jensen JP, Weissman AM, Ashwell JD. Ubiquitin protein ligase activity of IAPs and their degradation in proteasomes in response to apoptotic stimuli. Science. 2000;288:874–877. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce MC, et al. Regulation of Nedd4-2 self-ubiquitination and stability by a PY motif located within its HECT-domain. Biochem J. 2008;415:155–163. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ryoo HD, Ciechanover A, Gonen H. Regulation of the Drosophila ubiquitin ligase DIAP1 is mediated via several distinct ubiquitin system pathways. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:861–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woelk T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of coupled monoubiquitination. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1246–1254. doi: 10.1038/ncb1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shmueli A, Tsai YC, Yang M, Braun MA, Weissman AM. Targeting of gp78 for ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation by Hrd1: Cross-talk between E3s in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ballar P, Ors AU, Yang H, Fang S. Differential regulation of CFTRDeltaF508 degradation by ubiquitin ligases gp78 and Hrd1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magnifico A, et al. WW domain HECT E3s target Cbl RING finger E3s for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43169–43177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clayton-Smith J, Laan L. Angelman syndrome: A review of the clinical and genetic aspects. J Med Genet. 2003;40:87–95. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.2.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka M, Gupta R, Mayer BJ. Differential inhibition of signaling pathways by dominant-negative SH2/SH3 adapter proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6829–6837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley ML, Keiger KE, Lee CJ, Huibregtse JM. The global transcriptional effects of the human papillomavirus E6 protein in cervical carcinoma cell lines are mediated by the E6-AP ubiquitin ligase. J Virol. 2005;79:3737–3747. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3737-3747.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.