Abstract

Background

Estimates of the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) (Hemoccult II) sensitivity differ widely between screening trials, and will lead to divergent conclusions on the effects of FOBT screening. We used microsimulation modeling to estimate a preclinical colorectal cancer (CRC) duration and sensitivity for unrehydrated FOBT from the data of 3 randomized controlled trials of Minnesota, Nottingham and Funen. In addition to two usual hypotheses on the sensitivity of FOBT, we tested a novel hypothesis where sensitivity is linked to the stage of clinical diagnosis in the situation without screening.

Methods

We used the MISCAN-Colon microsimulation model to estimate sensitivity and duration, accounting for differences between the trials in demography, background incidence and trial design. We tested three hypotheses for FOBT sensitivity: sensitivity is the same for all preclinical CRC stages, sensitivity increases with each stage, and sensitivity is higher for the stage in which the cancer would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening than for earlier stages. Goodness of fit was evaluated by comparing expected and observed rates of screen-detected and interval CRC.

Results

The hypothesis with a higher sensitivity in the stage of clinical diagnosis gave the best fit. Under this hypothesis, sensitivity of FOBT was 51% in the stage of clinical diagnosis and 19% in earlier stages. The average duration of preclinical CRC was estimated at 6.7 years.

Conclusion

Our analysis corroborates a long duration of preclinical CRC, with FOBT most sensitive in the stage of clinical diagnosis.

Keywords: Colorectal Neoplasms, Occult Blood, Sensitivity and Specificity, Statistical Models

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in developed countries.1 Because prognosis for CRC is mainly related to the extent of tumor spread at the time of diagnosis, earlier presymptomatic diagnosis offers hope of mortality reduction. Three large randomized trials have conclusively shown that screening with the Hemoccult II fecal occult blood test (FOBT) can reduce CRC mortality by 11%-33%.2-4

FOBT trials provide information on estimates of mortality reduction, as well as rates of screen-detected CRC, stage distribution of screen-detected CRC and interval cancers. This information can be used to obtain estimates of sensitivity of FOBT and sojourn time (i.e. the duration of the preclinical screen-detectable cancer period). Sensitivity of FOBT screening has been estimated individually for each screening trial, but these estimates differ from 54-59% for the Nottingham trial,5 62% for the Funen trial,6 to 94-96% for the Minnesota trial.7 These differences can at least partly be explained by differences in estimation methods. Using different estimates for sensitivity and how it relates to sojourn time to make predictions of CRC screening beyond the trial setting, will lead to diverging conclusions concerning the (cost-) effectiveness of FOBT screening. This not only holds for the guaiac FOBT, but also for new and more sensitive FOBTs, for which no randomized controlled trial results are available.

In this study, we used the MISCAN-Colon microsimulation model to estimate unrehydrated FOBT sensitivity and preclinical CRC duration simultaneously on the randomized controlled FOBT trials of Minnesota, Nottingham and Funen. Although, the methodology used is standard (we simulated the trials and evaluated with which values of sensitivity and duration the expected (i.e. simulated) outcomes are closest to the observed),8, 9 the exceptionality of this analysis I that we simulated three trial populations instead of one. Besides the usual hypotheses where FOBT sensitivity is the same for all CRC stages or increases with stage, we also evaluated a novel hypothesis where sensitivity is linked to the stage in which the cancer would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening. In the model each clinical CRC diagnosis in a certain stage is preceded by a preclinical phase in the same stage. In the novel hypothesis, we assumed that sensitivity was higher in this preclinical stage than in the earlier stages.

Material and Methods

FOBT trials

Table 1 contains an overview of the most important differences in trials design between the Minnesota, Nottingham and Funen trials, which we accounted for.

Table 1.

Overview of differences in design of three large FOBT screening trials. All three trials used 6-slide Hemoccult II FOBT.

| Minnesota | Nottingham | Funen | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1975-1992* | 1981-1995 | 1985-2002 |

| Trial Population | Volunteers | General Population | General Population |

| Age at entry | 50-80 years | 45-75 years | 45-75 years |

| Interval | 1 year or 2 years | 2 years | 2 years |

| Rounds | 11 in yearly group | 3-6† | 9# |

| Invitation schedule | All were re-invited | Only attending individuals re-invited. From 1990 all were re-invited | Only attending individuals were re-invited |

| Test | Unrehydrated, later rehydrated | Unrehydrated | Unrehydrated |

| Dietary restrictions | Yes | No | Yes |

| Follow-up | Mainly Colonoscopy | 4 or less slides positive: re-test and eventually colonoscopy 5 or more positive: mainly colonoscopy | Colonoscopy |

| 5 or more positive: mainly colonoscopy |

FOBT: Fecal Occult Blood Test

Screening was not performed in the period 1982-1986

Results of first 5 rounds used

Results of first 8 rounds used

The Minnesota trial was originally designed to screen and follow participants from 1975 through 1982.10 In this period 46,551 participants aged 50 to 80 years were recruited among volunteers in Minnesota. In February 1986, screening was re-instituted and continued through February 1992. Participants were randomly assigned to screening once a year, to screening once every two years, or to a control group. Participants in the two screening groups were each asked to collect two samples from three consecutive stools on a Hemoccult II FOBT-kit. The participants were instructed to abstain from dietary factors influencing the specificity of the test. Initially the slides were processed unrehydrated; from 1977 onwards, slides were rehydrated with a drop of deionized water to increase sensitivity. Persons with one or more slides testing positive were referred for diagnostic follow-up, mainly by colonoscopy. All persons alive without CRC were re-invited for screening after one year or two years, depending on the study arm. Controls were not invited for screening. Eighteen years after initiation, the study reported a 33% CRC mortality reduction in the annual arm and 21% in the biennial arm.4

From 1981 to February 1995, 152,850 subjects from the area of Nottingham were randomly allocated to biennial FOBT screening or no screening (controls).2 Controls were not informed about the study. FOBTs were not rehydrated and dietary restrictions were imposed only for retesting borderline results (4 or less positive slides). Screening-group participants with a positive test were offered full colonoscopy. Initially, individuals who attended screening were invited to take part in further screening every two years. From 1990 onwards, also non-attenders to screening were re-invited. After 14 years, the study reported a 15% reduction in CRC mortality in the intervention group.

From 1985 to 2002, 61,933 inhabitants of Funen, Denmark aged 45-74 year were randomly allocated to either FOBT screening every two years or no intervention. 6-slide Hemoccult-II blood tests (with similar dietary restrictions as in Minnesota but without rehydration) were sent to screening-group participants. Only participants who completed screening were invited for further rounds. Participants with positive tests were offered colonoscopy whenever possible. The reported mortality reduction in this study was 18% after seven screening rounds.3

MISCAN-Colon

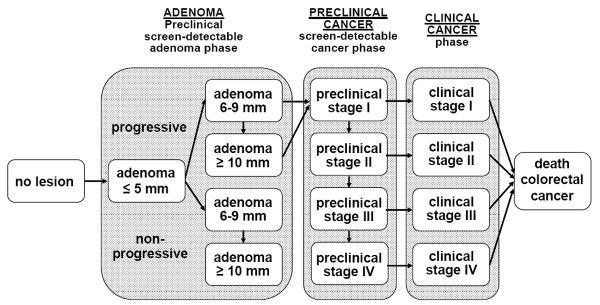

The MISCAN-Colon microsimulation model was developed at the Department of Public Health at Erasmus MC, the Netherlands, in collaboration with the US National Cancer Institute and experts in the field of CRC to assess the effect of different interventions on CRC. A graphical representation of the natural history in the model is given in Figure 1. A detailed description and the data sources that inform the quantification of the model can be found in previous studies,11-13 and in a standardized model profiler.14 In brief, the MISCAN-Colon model simulates the relevant biographies of a large population of individuals from birth to death, first without screening and subsequently the changes that would occur under the implementation of screening. CRC arises in this population from the development of adenomatous polyps which may progress to carcinoma.15, 16 More than one adenoma can occur in an individual and each can independently develop into CRC. Adenomas progress in size from small (1-5 mm) to medium (6-9 mm) to large (10+ mm). Some of the adenomas eventually become malignant, transforming to a localized (Dukes A) cancer. The cancer can then progress through Dukes B and C stages to metastasized (Dukes D) cancer. In every stage there is a chance of diagnosis of the cancer because of symptoms. The survival after clinical diagnosis depends on the stage in which the cancer was detected.

Figure 1.

Adenoma and cancer stages in the MISCAN-Colon model. Cancer stages correspond to the Dukes staging system for colorectal cancer. Adenomas are categorized by size. The size-specific prevalence of adenomas as well as the proportion of adenomas that ever develop into cancer is dependent on age. It is assumed that the proportion of progressive adenomas increases from 16% at age 65 to 37% at age 75, and 96% at age 100. It is assumed that 50% of non-progressive adenomas will remain 6-9 mm stage until death and that 50% will progress to the ≥10 mm stage. For progressive adenomas, it is assumed that 30% will develop through the sequence ≤5 mm adenoma → 6-9 mm adenoma → preclinical cancer stage I and that 70% will develop through the sequence ≤5 mm adenoma →6-9 mm adenoma → ≥10 mm adenoma → preclinical cancer stage I. The mean duration time for progressive adenoma to clinical cancer is assumed to be 20 years (with an exponential distribution). The model is calibrated to reproduce observed CRC incidence and stage distribution in the control groups for each of the three trials (see Methods and Materials).

After the life-history of an individual in the absence of screening is generated, the model simulates if and when screening interrupts the development of CRC in that same life-history. With screening, adenomas are detected and removed and cancers are detected and treated earlier in time. The probability of detection of a certain lesion depends on the sensitivity of the test for the stage the lesion is in. Because the life-history in the absence of screening is first simulated, the stage in which the cancer would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening is known in the model.

The model as quantified for the general US population,11, 13 served as the basis of this analysis. The model was the same for each trial with respect to the natural history of disease and FOBT sensitivity, but differed with respect to trial specific characteristics such as the age distribution of the eligible population, the attendance pattern and CRC risk. Table 2 contains an overview of model parameters that were adjusted to the trial-specifics. We assumed that differences in CRC incidence between the general US population and the control groups in the three trials, were caused by differences in adenoma onset, and we adjusted the adenoma risk parameter accordingly (Table 2). Also, the probability of clinical diagnosis for each CRC stage was varied between the trials, reflecting differences in stage distribution of CRC in the control groups. Screening ages, invitation protocol and compliance with screening and follow-up of positive test results were explicitly modeled in each population according to what was observed in each of the corresponding trials. As observed in the trials in first and consecutive rounds, not all invited individuals attend screening in the model. Each invited individual has a certain probability to attend first screening. For consecutive screenings, previous attenders have a higher probability to attend the consecutive screen round than non-attenders. The adenoma risk in the non-attenders was adjusted to reproduce observed CRC incidence in this group in each trial. Because based on randomization, on average the CRC risk in the total intervention group should match that of the control group, the attenders were left with a correspondingly lower adenoma risk. Because of the difference in dietary restrictions between the trials, specificity of FOBT was allowed to vary between the three trials. With this complete set of adjustments, simulated incidence and stage distribution of the control group were within 1% of observed for all three trials (data not shown).

Table 2.

MISCAN-Colon model parameters as adjusted specifically to the trials.

| Parameter | Minnesota | Nottingham | Funen |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1975-1981, 1987-1992 | 1981-1995* | 1985-2000† |

| Birth years population | 1895-1925 | 1906-1936 | 1910-1940 |

| RR for incidence compared to US population 1978 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.92 |

| RR for incidence non-attenders versus attenders | 1 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Stage distribution clinically diagnosed CRC | |||

| Dukes A | 25% | 13% | 12% |

| Dukes B | 34% | 35% | 38% |

| Dukes C | 23% | 31% | 24% |

| Dukes D | 19% | 21% | 26% |

| 10-years survival by stage | |||

| Dukes A | 91% | 87% | 87% |

| Dukes B | 75% | 69% | 69% |

| Dukes C | 44% | 43% | 43% |

| Dukes D | 1% | 4% | 4% |

| Screen interval | 1 year or 2 years | 2 years | 2 years |

| Attendance to | |||

| first screen | Age-dependent: 56-81% | 63% | 67% |

| repeat screen, if attended previously | 90% | 87% | 93% |

| repeat screen, if not attended previously | 42% | 14% | not re-invited: 0% |

| Specificity | Unrehydrated: 98% | 99% | 99% |

| Rehydrated: 90% |

RR: Relative risk

CRC: Colorectal Cancer

Results of first 5 rounds used

Results of first 8 rounds used

Sensitivity hypotheses and duration

We assessed three different hypotheses for FOBT sensitivity:

- Hypothesis A: Sensitivity of FOBT is the same for all four preclinical cancer stages (one parameter).

- Hypothesis B: Sensitivity of FOBT increases with each preclinical cancer stage (four parameters).

- Hypothesis C: Sensitivity of FOBT is higher in the stage in which the cancer would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening than in earlier stages (two parameters).

Four parameters for average duration were estimated, one for each preclinical CRC stage.

In the Minnesota trial, both unrehydrated and rehydrated FOBT were used. As part of the estimation procedure, we therefore also estimated sensitivity for rehydrated FOBT assuming the same hypotheses as for unrehydrated FOBT. Because the Nottingham and Funen trials did not rehydrate tests, rehydrated FOBT was not the focus of our analysis.

Analysis

The sensitivity and duration parameters for each hypothesis were estimated by minimizing the difference between observed and expected trial outcomes. Trial outcomes used for estimation were: 1) screen-detected cancers by screening round, 2) stage distribution of screen-detected cancers for first and consecutive screening rounds and 3) interval cancers by years since negative screening. Because the trials differed in number of screening rounds and interval, the number of outcomes per trial was different. There were 26 outcomes for Minnesota, 15 for Nottingham and 18 for Funen. The corresponding expected outcomes were generated per trial with the MISCAN-Colon microsimulation model. The significance of the difference between observed and expected outcomes was assessed by the following chi-square statistic:

The overall chi-square statistic of each hypothesis was calculated as the sum of the chi-square statistics of the individual outcomes. We assumed outcomes to be independent and uncorrelated. This overall chi-square statistic was minimized with an adaptation of the Nelder-and-Mead Simplex Method.8 The Nelder-and-Mead method is a common approach to estimating parameters with microsimulation models, because derivatives of equations of these models are often too complex to use Maximum-Likelihood approaches. The resulting chi-square statistic after estimation of the parameters was a measure of the goodness of fit of each hypothesis. The degrees of freedom of the chi-square statistic were equal to the total number of trial outcomes compared minus the number of parameters under the respective hypothesis. The chi-square statistics of hypotheses B and C could not be directly compared statistically because there is no hierarchical relationship between the hypotheses. We used the Akaike Information Criterion to compare these two hypotheses. We assumed the outcomes were Poisson distributed. The formula for the Akaike Information Criterion with Poisson distributed outcomes is:

The Akaike Information Criterion is a standard tool for model selection, with the model having the lowest value being the best.

We also derived conditional confidence intervals around the estimated parameters. We determined to what values we could change each of the estimated parameters without significantly worsening the goodness-of-fit of the model. The values closest to the estimated parameter at which the goodness-of-fit of the model significantly worsened (p=0.05), constituted the boundaries of the confidence interval.

Results

Sensitivity and duration

Table 3 shows the estimates for sensitivity and duration. Assuming the same sensitivity of FOBT for all preclinical CRC stages, resulted in shorter duration of Dukes A and B (1.6 and 2.1 years) than in Dukes C and D (4.0 and 3.2 years), due to higher detection rates in later stages than in earlier ones. With these durations it took on average 6.0 years for a preclinical cancer to become clinically diagnosed. The estimated sensitivity of FOBT under this hypothesis was 33%. Assuming a higher sensitivity of FOBT with each Dukes stage resulted in a longer duration for Dukes A and C (3.8 and 3.6 years respectively) compared with Dukes B and D (2.4 and 2.1 years). The average duration of preclinical CRC was 8.0 years. The sensitivity of FOBT is comparable for Dukes B and C disease (35-38%), and lower for Dukes A (13%) and higher for Dukes D (66%). Assuming a higher sensitivity of FOBT in the stage of clinical diagnosis, Dukes C has longer duration (3.7 years) than the other three stages (2.5 years for Dukes A and B and 1.5 years for Dukes D). The average duration of preclinical CRC is 6.7 years. Sensitivity is considerably higher in stage of clinical diagnosis than in earlier stages (51% versus 19%).

Table 3.

Estimated values (confidence interval) for sensitivity of FOBT and duration of preclinical CRC for three sensitivity hypotheses

| Parameters | Hypothesis A | Hypothesis B | Hypothesis C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average duration in years | |||

| Dukes A | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 3.8 (3.3-4.2) | 2.5 (2.3-2.8) |

| Dukes B | 2.1 (1.9-2.5) | 2.4 (2.1-2.7) | 2.5 (2.2-3.0) |

| Dukes C | 4.0 (3.2-4.6) | 3.6 (3.0-4.3) | 3.7 (3.1-4.7) |

| Dukes D | 3.2 (2.2-4.3) | 2.1 (1.4-2.8) | 1.5 (1.2-2.7) |

| Total* | 6.0 (5.2-6.9) | 8.0 (7.1-9.0) | 6.7 (5.8-7.7) |

| Sensitivity unrehydrated FOBT (%):† | |||

| Dukes A | 33 (30-37) | 13 (12-16) | |

| Dukes B | 33 (30-37) | 35 (33-42) | |

| Dukes C | 33 (30-37) | 38 (36-44) | |

| Dukes D | 33 (30-37) | 66 (61-76) | |

| Stage of clinical diagnosis | 51 (47-65) | ||

| Earlier stages | 19 (16-25) |

FOBT: Fecal Occult Blood Test

CRC: Colorectal Cancer

Hypothesis A: same sensitivity of FOBT for all cancer stages.

Hypothesis B: sensitivity different for each cancer stage.

Hypothesis C: sensitivity of FOBT different in stage of clinical diagnosis than in earlier stages.

Calculated as (% in stage A * duration A) + (% in stage B * duration A+B) + (% in stage B * duration A+B+C) + (% in stage D * duration A+B+C+D)

For the Minnesota trial sensitivity of rehydrated FOBT were: 28% for Hypothesis A; 10% Dukes A, 26% Dukes B, 56% Dukes C and 63% Dukes D for Hypothesis B; 55% stage of clinical diagnosis, 10% earlier stages for Hypothesis C.

Goodness-of-fit

Comparison of aggregated trial results

Table 4 shows observed and expected detection and interval cancer rates aggregated for the three FOBT trials and the associated goodness of fit for each hypothesis. For hypothesis A, the expected outcomes differed significantly from observed (p<0.01). This was mainly due to a significantly lower number of expected screen-detected cancers in Dukes A (first round, 91 expected vs. 116 observed), and a significantly higher rate of interval cancers in the first two years after screening (432 expected versus 369 observed). For hypothesis B, the expected outcomes also differed significantly from observed (p<0.01). Three expected outcomes under this hypothesis were different from observed: like with hypothesis A, the expected number of first round screen-detected cancer cases in Dukes A was lower than observed (93 vs. 116) and the number of interval cancers was higher than observed (421 vs. 369). Moreover, the observed number of screen-detected cancer cases in stage B in consecutive screen rounds was 157, where 134 were expected. Hypothesis C had the lowest chi-square statistic (Table 4). Although none of the expected outcomes aggregated over the three trials differed significantly from observed under hypothesis C, summed together the outcomes significantly differed (p=0.02). Nonetheless, hypothesis C was significantly better than hypothesis A (p<0.01), whereas hypothesis B was not significantly better than hypothesis A (p=0.37). Finally, hypothesis C had a better goodness-of-fit than hypothesis B with fewer parameters. This also showed from the Akaike Information Criterion, which was -10,582 for hypothesis C, better than the -10,563 for hypothesis B.

Table 4.

Observed and expected screen-detected CRC, stage distribution of screen-detected cancers by phase for first and consecutive rounds and interval cancers and chi-square statistic for three hypotheses for FOBT sensitivity, three trials aggregated

| Outcome | Observed | Expected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis A 6 parameters | Hypothesis B 12 parameters | Hypothesis C 8 parameters | ||

| Screen-detected CRC, round 1 | ||||

| Cases (rate per 1,000 persons screened) | 247 (2.21) | 256 (2.29) | 249 (2.23) | 256 (2.29) |

| Cases (%) Dukes A | 116 (48) | 91 (38)* | 93 (39)† | 101 (42) |

| Cases (%) Dukes B | 60 (25) | 76 (32) | 69 (29) | 76 (32) |

| Cases (%) Dukes C | 52 (22) | 59 (24) | 63 (26) | 53 (22) |

| Cases (%) Dukes D | 12 (5) | 14 (6) | 15 (6) | 11 (5) |

| Screen-detected CRC, consecutive rounds | ||||

| Cases (rate) per 1,000 persons screened | 492 (1.56) | 531 (1.68) | 529 (1.68) | 522 (1.66) |

| Cases (%) Dukes A | 178 (39) | 204 (45) | 202 (44) | 202 (44) |

| Cases (%) Dukes B | 157 (34) | 137 (30) | 134 (29)† | 142 (31) |

| Cases (%) Dukes C | 98 (21) | 94 (21) | 101 (22) | 92 (20) |

| Cases (%) Dukes D | 25 (5) | 23 (5) | 21 (5) | 22 (5) |

| Interval cancers (rate) in first two years after screening per 1,000 person years | 369 (0.73) | 432 (0.85)* | 421 (0.83)† | 386 (0.76) |

| Chi-square statistic# | 83* | 76* | 73† | |

| Akaike Information Criterion# | -10,569 | -10,563 | -10,582 | |

CRC: Colorectal Cancer

FOBT: Fecal Occult Blood Test

Expected outcome significantly different from observed (p < 0.01)

Expected outcome significantly different from observed (p < 0.05)

Based on 59 trial specific outcomes

Hypothesis A: Same sensitivity for all cancer stages

Hypothesis B: Sensitivity different for each cancer stage

Hypothesis C: Sensitivity is higher in stage of clinical diagnosis

Comparison of detailed trial specific results (results not shown)

Under hypothesis C, five expected trial-specific outcomes differed significantly from observed: the expected interval cancer rate in the first year after screening in the Minnesota trial; the expected number of screen-detected cases in the first screening round in the Nottingham trial; and the number of screen-detected cases in the first screening round, the number of screen-detected cases in the second round and the percentage of screen-detected cases in Dukes B in the Funen trial. In addition to these outcomes, there were three other significant differences under hypotheses A and B: the expected rate of interval cancers in the second year after screening in the Minnesota trial; the interval cancers after the first screening round in the Nottingham trial; and the screen-detected cancers in the seventh round in the Funen trial.

Discussion

We have fitted sensitivity and duration for three different sensitivity models to the Minnesota, Nottingham and Funen trial results. We found that the hypothesis in which sensitivity of FOBT is highest in the stage in which the cancer would have been clinically diagnosed in the absence of screening gave the best fit with an estimate of 51%. In earlier stages, estimated sensitivity was 19%. The mean preclinical CRC duration was estimated at 6.7 years.

The hypothesis that sensitivity of FOBT is highest in the stage of clinical diagnosis was best for three reasons. Firstly, it gave the best statistical fit to observed trial outcomes (although differences in goodness-of-fit between the hypotheses are small). Secondly, it is also biologically the most plausible one, because tumor bleeding resulting in (macroscopic) detection of blood in stool is often the symptom leading to clinical detection of CRC. About 34%-58% of CRC present with rectal bleeding.17-20 It is very plausible that occult bleeding precedes macroscopic bleeding and thus that sensitivity of FOBT depends on time to clinical diagnosis. Interestingly the range of cancers that present with bleeding compares well with our sensitivity estimate of 51%. Thirdly, this hypothesis is able to explain the discrepancy between the high FOBT sensitivity estimates based on trial results (54%-96%)5-7 and the low estimates based on back-to-back studies with colonoscopy (11-50%).21-26 With a 1-2 year screening interval, trials mainly estimate sensitivity in the last phase of cancer progression, i.e. the stage before diagnosis in the absence of screening. Our sensitivity estimate of 51% for this phase, is in line with the individual estimates by the investigators of the Nottingham and Funen trials.5, 6 Colonoscopy is sensitive for all stages of CRC and showed that FOBT detects a much smaller proportion of all CRC. The weighted average of our sensitivity in stage of clinical diagnosis and our sensitivity in earlier stages of 32% is in line with that observation.

In all three trials the observed stage distribution in repeat screening rounds is less favorable than the stage distribution in the first screening round, while for all three hypotheses this is predicted to be the other way around. This discrepancy can be explained by assuming the presence of occult bleeding indolent cancers (i.e. early-stage cancers never progressing or giving symptoms), especially in stage A. These indolent cancers would be detected during first screening, allowing for many early stage cancers in the first screening round. At consecutive screening rounds these cancers would no longer be present, so that then fewer early-stage cancers are detected. This would be adding a considerable amount of length-biased sampling. With the current assumption of an exponential distribution, there already is a considerable variability in the duration of CRC and therefore amount of length-biased sampling accounted for in the model, but modeling indolent cancers would further increase length-biased sampling. This would potentially further improve the fit of the model, not only for the favorable stage distribution in first screenings but potentially also regarding the sensitivity of rehydrated FOBT. Currently, our estimate for rehydrated FOBT in stages before the stage of clinical detection is lower than for unrehydrated FOBT. Several studies have shown that rehydration of FOBT slides increases sensitivity.10, 27-30 Rehydration of FOBT slides was mainly done in the second phase of the Minnesota trial with only follow-up screening rounds. Because the modeled detection rates in follow-up rounds, and thus in this phase, are higher than observed, the estimated sensitivity for rehydrated FOBT needed to be low to compensate. With indolent cancers, the detection rates at consecutive screenings would be lower and consequently the estimate for rehydrated FOBT sensitivity higher.

Dividing FOBT sensitivity in a phase with low sensitivity and a phase with high sensitivity is a novel way of describing the occult blood detection process. Despite its plausibility, this hypothesis was never tested, may be because it can not be observed in studies (time of clinical manifestation of a disease is not known), or estimated through classical sensitivity estimation. With microsimulation, time of clinical manifestation is pseudo-observed and therefore sensitivity of the test can be varied accordingly. But up to now, microsimulation models have assigned a certain sensitivity of FOBT for preclinical CRC stages, regardless of when individual cancers become clinical.31 In these models, sensitivity was not varied at all between stages (our hypothesis A).

Our improved estimates can be used to better extrapolate the trial results to newer and more sensitive FOBTs, for which no randomized controlled trial results are available. Because these tests have higher sensitivity, one could argue that the screening interval could be lengthened with these tests. However, the mechanism of detection of occult blood is the same for these tests, so it is likely that these more sensitive tests are also mainly sensitive for lesions shortly before clinical diagnosis. Therefore also with a higher sensitivity, it will remain important to screen with FOBT frequently. Our results also have implications for endoscopy screening. Although the attention of endoscopy is often on detection and treatment of pre-cancerous adenomas, the effectiveness due to detection of cancers in an (very) early stage is stressed by this analysis. A longer preclinical CRC duration improves the efficacy of endoscopy screening. All together, the improved model will be more fitted to compare (newer) FOBT testing to endoscopy screening. In order to test the 6.7 years dwell time for preclinical cancer as estimated here, the CRC detection rates of endoscopy together with incidence in the control group are required.

In conclusion, the results of the Minnesota, Nottingham and Funen trials were best explained by the hypothesis that FOBT becomes more sensitive shortly before clinical diagnosis. The total preclinical cancer duration was estimated to be as long as 6.7 years. FOBT has only 20% sensitivity for the majority of this period. Only for cancers in the stage in which the cancer would have been diagnosed in the absence of screening (on average the last 2.5 years before diagnosis), sensitivity becomes 50%.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to their collaborators in this study: Prof. O. Kronborg, Mrs. Dr. D. Gyrd-Hansen, Odense University Hospital, Prof. J. Faivre, Mrs. Dr. C. Lejeune, Burgundy Cancer Registry, Prof. J.D. Hardcastle, Prof. D.K. Whynes, University of Nottingham, Dr. N. Segnan, Dr. G. Castiglione, Dr. C. Senore, Centro Prevenzione Oncologica Regione Piemonte, Dr. G. Hoff, Telemark Central Hospital, Dr. E Thiis-Evensen, Riskhospitalet, Dr. H. Brevinge, Sahlgrens Hospital, Dr. T. Church, University of Minnesota, Dr. F. Loeve and Dr. G. van Oortmarssen, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam. Their cooperation was essential for the successful completion of the study.

Funding: European Commission (99/CAN/36898); National Cancer Institute (U01 CA97426)

Biography

Rob Boer has participated since 1989 in the screening research group at the Department of Public Health of the Erasmus MC. He is affiliated with RAND since 2000. Since 2007, he is a Director of Evidence Based Strategies - Disease Modeling and Economic Evaluation at Pfizer Inc, which develops and sells various medicines for cancer and other diseases. This research and article were not funded or supported by Pfizer.

Footnotes

All authors declare to have no proprietary, financial, professional or other personal interest of any nature in any product, service and/or company that could be affected by the position presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorgensen OD, Kronborg O, Fenger C. A randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood testing: results after 13 years and seven biennial screening rounds. Gut. 2002;50:29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:434–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss SM, Hardcastle JD, Coleman DA, Robinson MH, Rodrigues VC. Interval cancers in a randomized controlled trial of screening for colorectal cancer using a faecal occult blood test. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:386–90. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gyrd-Hansen D, Sogaard J, Kronborg O. Analysis of screening data: colorectal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:1172–81. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.6.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church TR, Ederer F, Mandel JS. Fecal occult blood screening in the Minnesota study: sensitivity of the screening test. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1440–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neddermeijer HG, Piersma N, Oortmarssen GJv, Habbema JDF, Dekker R. Comparison of response surface methodology and the Nelder and Mead simplex method for optimization in microsimulation models. Econometric Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright MH. Direct Searh Methods: once scorned, now respectable. In: Griffiths DF, Watson GA, editors. Numerical Analysis 1995 (Proceedings of the 1995 Dundee Biennial Conference in Numerical Analysis) Addison Wesley Longman; Harlow, United Kingdom: 1996. pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, et al. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeve F, Boer R, Ballegooijen Mv, Oortmarssen GJv, Habbema JDF. Final Report MISCAN-COLON Microsimulation Model for Colorectal Cancer. Department of Public Health, Erasmus University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeve F, Boer R, van Oortmarssen GJ, van Ballegooijen M, Habbema JDF. The MISCAN-COLON simulation model for the evaluation of colorectal cancer screening. Comput Biomed Res. 1999;32:13–33. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1998.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loeve F, Brown ML, Boer R, van Ballegooijen M, van Oortmarssen GJ, Habbema JD. Endoscopic colorectal cancer screening: a cost-saving analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:557–63. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.7.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, et al. Department of Public Health; Erasmus MC: 2004. [September 9, 2008]. Model Profiler of the MISCAN-Colon microsimulation model for colorectal cancer. Available from: http://cisnet.cancer.gov/profiles. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morson B. The polyp-cancer sequence in the large bowel. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:451–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muto T, Bussey HJR, Morson BC. The evolution of cancer of the colon and rectum. Cancer. 1975;36:2251–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820360944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyle SM, Isbister WH, Yeong ML. Presentation, duration of symptoms and staging of colorectal carcinoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991;61:137–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lanier AP, Wychulis AR, Dockerty MB, Elveback LR, Beahrs OH, Kurland LT. Colorectal cancer in Rochester, Minnesota 1940-1969. Cancer. 1973;31:606–15. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197303)31:3<606::aid-cncr2820310317>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majumdar SR, Fletcher RH, Evans AT. How does colorectal cancer present? Symptoms, duration, and clues to location. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3039–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speights VO, Johnson MW, Stoltenberg PH, Rappaport ES, Helbert B, Riggs M. Colorectal cancer: current trends in initial clinical manifestations. South Med J. 1991;84:575–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allison JE, Tekawa IS, Ransom LJ, Adrain AL. A comparison of fecal occult-blood tests for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:155–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601183340304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins JF, Lieberman DA, Durbin TE, Weiss DG, Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study G Accuracy of screening for fecal occult blood on a single stool sample obtained by digital rectal examination: a comparison with recommended sampling practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:81–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-2-200501180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Turnbull BA, Ross ME, Colorectal Cancer Study G Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2704–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study G One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:555–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrelli N, Michalek AM, Freedman A, Baroni M, Mink I, Rodriguez-Bigas M. Immunochemical versus guaiac occult blood stool tests: results of a community-based screening program. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson MH, Marks CG, Farrands PA, Thomas WM, Hardcastle JD. Population screening for colorectal cancer: comparison between guaiac and immunological faecal occult blood tests. Br J Surg. 1994;81:448–51. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castiglione G, Biagini M, Barchielli A, et al. Effect of rehydration on guaiac-based faecal occult blood testing in colorectal cancer screening. Br J Cancer. 1993;67:1142–4. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1993.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kewenter J, Bjork S, Haglind E, Smith L, Svanvik J, Ahren C. Screening and rescreening for colorectal cancer. A controlled trial of fecal occult blood testing in 27,700 subjects. Cancer. 1988;62:645–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<645::aid-cncr2820620333>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levin B, Hess K, Johnson C. Screening for colorectal cancer. A comparison of 3 fecal occult blood tests. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:970–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macrae FA, St John DJ. Relationship between patterns of bleeding and Hemoccult sensitivity in patients with colorectal cancers or adenomas. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:891–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pignone M, Saha S, Hoerger T, Mandelblatt J. Cost-effectiveness analyses of colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:96–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]