Abstract

Background

Variability of gene expression in human may link gene sequence variability and phenotypes; however, non-genetic variations, alone or in combination with genetics, may also influence expression traits and have a critical role in physiological and disease processes.

Methodology/Principal Findings

To get better insight into the overall variability of gene expression, we assessed the transcriptome of circulating monocytes, a key cell involved in immunity-related diseases and atherosclerosis, in 1,490 unrelated individuals and investigated its association with >675,000 SNPs and 10 common cardiovascular risk factors. Out of 12,808 expressed genes, 2,745 expression quantitative trait loci were detected (P<5.78×10−12), most of them (90%) being cis-modulated. Extensive analyses showed that associations identified by genome-wide association studies of lipids, body mass index or blood pressure were rarely compatible with a mediation by monocyte expression level at the locus. At a study-wide level (P<3.9×10−7), 1,662 expression traits (13.0%) were significantly associated with at least one risk factor. Genome-wide interaction analyses suggested that genetic variability and risk factors mostly acted additively on gene expression. Because of the structure of correlation among expression traits, the variability of risk factors could be characterized by a limited set of independent gene expressions which may have biological and clinical relevance. For example expression traits associated with cigarette smoking were more strongly associated with carotid atherosclerosis than smoking itself.

Conclusions/Significance

This study demonstrates that the monocyte transcriptome is a potent integrator of genetic and non-genetic influences of relevance for disease pathophysiology and risk assessment.

Introduction

The transcriptome, i.e. the whole set of RNA transcripts in a cell, is generally conceived as a system whose major function is to pass information encoded in the genome sequence to the realm of phenotypes that underlie physiological and pathological traits. This messenger paradigm justifies the current interest for the genetics of gene expression [1]–[6] which has been further enhanced by the numerous associations between genetic markers and diseases reported in recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and the expected relevance of genome wide expression (GWE) to characterize the biological basis of these associations [7]–[10]. However the variability of gene expression not only reflects genetic variation but depends on other factors as well such as environmental exposures [11], [12], metabolic conditions [13], ageing [14], [15] or gender [16]–[17].

Based on these premises we reasoned that if the state of the transcriptome and its changes are important determinants of cell functions, differences in transcript abundance whatever their origin, genetic or non genetic, may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Moreover, the transcriptome might integrate information from numerous sources and inform on the current pathophysiological state of the organism. To assess these possibilities, a global characterization of the variability of the transcriptome, integrating genetic and non genetic influences was undertaken. The study focused on peripheral blood monocytes because these cells may be isolated from an easily accessible tissue and play a key role in the pathogenesis of immune disorders and atherosclerosis-related diseases [18]. In addition, working on a single cell type reduces the complexity of transcriptome data and may avoid possible biases resulting from the heterogeneous cell-types distribution in different samples as it is the case when using whole blood or leucocytes RNAs.

Results

The genome-wide expression of circulating monocytes

To reduce potential artefacts, fresh samples were collected and processed in a short period of time according to a very strict protocol. Monocytes were obtained from 1,490 unrelated individuals, 730 women and 760 men, aged 35 to 74 years, recruited in the Gutenberg Heart Study (GHS), a community-based project conducted in a single centre in the region of Mainz (Germany) ( Table 1 ). GWE profiles were generated using Illumina Human HT-12 expression BeadChips, and after normalization and filtering out genes undetected in monocytes or non-well characterized (see Materials and Methods), 12,808 expressions traits (averaged over probes) remained for analysis.

Table 1. Description of the GHS study population.

| Men | Women | P-value | |

| N | 760 | 730 | |

| Age (years) | 56.4 (10.6) | 53.9 (11.2) | 2.4×10−5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 (3.9) | 26.2 (5.1) | 1.2×10−8 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.4 (14.9) | 69.2 (17.8) | 2.2×10−16 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 133.7 (36.1) | 133.0 (36.8) | NS |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 143.2 (97.5) | 114.4 (56.8) | 2.1×10−12 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135.8 (16.7) | 128.5 (18.2) | 2.3×10−16 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 85.2 (9.6) | 81.2 (9.5) | 5.4×10−16 |

| Current smoker | 128 (16.8%) | 113 (15.5%) | NS |

| Plasma CRP (mg/L) (sqrt) | 1.509 (0.818) | 1.545 (0.743) | NS |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 97.8 (18.5) | 91.8 (15.4) | 1.1×10−4 |

Values are means (SD) or numbers (%).

Identification of eSNPs and eQTLs

Genotyping was performed using Affymetrix 6.0 arrays. After filtering out SNPs poorly performing or having a minor allele frequency <0.01, 675,350 SNPs were kept for further analyses. All associations between SNPs and expression traits with a P-value <10−5 (n>225,000) were stored in the “GHS_Express” database (“GHS_Express” is available online, see Methods S1 ). At a study-wise threshold of significance correcting for the number of SNPs and expressions (P<5.78×10−12), 37,403 associations, involving 29,912 SNPs and 2,745 expression traits (referred to as eSNPs and eQTLs, respectively), were identified ( Table 2 ). The median number of eSNPs by eQTL was 11 with an interquartile range of 4 to 26. Owing to its large sample size, the study had an 80% power to detect a SNP effect accounting for 4% or more of the variability (R2) of any expression trait. Among the 2,745 significant eQTLs, the R2 observed for the best eSNP varied from 3.1% to >80% with a median of 7.7%. For 290 eQTLs, the R2 was greater than 25%.

Table 2. Number of gene expression-by-SNP associations at various levels of significance.

| Significance level | Minimum R2 $ | Total number of associations | cis/trans ratio for associations | Total number of associated expressions (eQTLs) | cis/trans ratio for eQTLs | Total number of associated SNPs (eSNPs) | cis/trans ratio for eSNPs |

| <10−6 | 0.016 | 93491 | 2.1 | 8575 | 0.5 | 67190 | 2.4 |

| <10−8 | 0.022 | 54749 | 7.3 | 3857 | 3.0 | 41425 | 11.2 |

| <10−10 | 0.028 | 42421 | 9.8 | 2998 | 6.0 | 33339 | 16.3 |

| <5.78×10−12 | 0.031 | 37403 | 10.7 | 2745 | 7.1 | 29912 | 17.1 |

| <10−15 | 0.042 | 27330 | 12.7 | 2180 | 9.5 | 22591 | 17.8 |

| <10−20 | 0.057 | 19655 | 14.7 | 1725 | 12.8 | 16883 | 19.2 |

| <10−25 | 0.071 | 15015 | 16.4 | 1429 | 16.2 | 13045 | 21.5 |

| <10−35 | 0.099 | 9673 | 17.1 | 1031 | 21.6 | 8516 | 22.9 |

| <10−50 | 0.140 | 5873 | 14.0 | 712 | 28.8 | 5224 | 21.7 |

| <10−100 | 0.263 | 1790 | 10.5 | 290 | 28.1 | 1598 | 11.1 |

| <10−150 | 0.371 | 922 | 5.5 | 156 | 21.4 | 772 | 5.9 |

| <10−200 | 0.463 | 635 | 3.7 | 97 | 15.3 | 504 | 3.9 |

| <10−300 | 0.606 | 321 | 1.7 | 38 | 11.7 | 213 | 1.7 |

Minimum R2 (proportion of gene expression variability explained by a SNP) observed for a given significance level. Numbers corresponding to study-wise significance are shown in bold. For investigating cis associations or performing any other hypothesis-based test, lower levels of significance may be considered.

Cis versus trans associations

Associations involving SNPs located within 1 Mb of either the 5′ or 3′ end of the associated gene were considered cis ( File S1 ) and other associations were considered trans. In accordance with previous results [2]–[6], most of the genetic variability affecting the transcriptome was of cis origin. At study-wise significance, the number of cis and trans eQTLs were 2,477 and 349, respectively, yielding a cis/trans ratio of 7.1 (81 eQTLs were both cis- and trans-modulated). At less stringent levels of significance the number of trans associations considerably increased, as expected by chance, whereas the number of cis eQTLs only modestly increased, indicating that the high stringency used for cis eQTLs identification did not result in an important under-estimation of the true number of cis eQTLs ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Number of eQTLs according to the significance threshold adopted and corresponding cis/trans eQTL ratio.

The vertical arrow indicates the study-wise level of significance correcting for the number of hypotheses tested. Some eQTLs being associated with both cis and trans-acting eSNPs, the sum of cis and trans eQTLs is greater than the total number of eQTLs.

Comparison with previous GWAS of gene expression

We examined the overlap between the cis eQTLs identified in the present study and those found in three previous association studies in which gene expression was explored in LCLs [1], [2] and hepatic cells [3]. For this comparison, a significance threshold of 3.9×10−6 (Bonferroni-corrected for 12,808 genes) was used for the analysis of eQTLs in GHS data, corresponding to a single hypothesis tested per gene. Among the cis eQTLs considered significant in each of the studies and involving expression traits detected in GHS, 66.7%, 56.5% and 54.1%, respectively, were significant in our data ( Table 3 , Files S2–S4). The proportion of cis eQTLs that replicated in GHS increased with the increasing level of significance reported in each study, consistent with the fact that stronger associations are more robust and more likely to be shared by different types of cells. These comparisons revealed a relatively high rate of replication of the previous findings in GHS. However, as a consequence of its greater power, P-values observed in GHS were considerably lower than those previously reported ( Figure 2 ).

Table 3. Number of cis eQTLs identified in previous studies and replicated in GHS.

| Stranger et al. | Dixon et al. | Schadt et al. | ||||

| Level of signifi-cance | Number of eQTLs at level of significance | Percent signifi-cant in GHS* | Number of eQTLs at level of significance | Percent significant in GHS* | Number of eQTLs at level of significance | Percent signifi-cant in GHS* |

| >10−8 | 86 | 55.8 | 110 | 50.9 | 928 | 47.9 |

| 10−8–10−10 | 63 | 69.8 | 162 | 50.0 | 168 | 57.7 |

| 10−10–10−15 | 144 | 63.2 | 237 | 54.8 | 211 | 57.3 |

| 10−15–10−20 | 60 | 70.0 | 102 | 60.7 | 120 | 66.7 |

| 10−20–10−25 | 38 | 89.5 | 73 | 65.7 | 73 | 67.1 |

| ≤10−25 | 48 | 70.8 | 89 | 67.4 | 103 | 73.8 |

| All | 439 | 66.7 | 773 | 56.5 | 1603 | 54.1 |

* Comparisons were based on sets of gene expressions overlapping between each study and GHS and were restricted to autosomal cis eQTLs. All cis eQTLs considered significant in each study were retrieved and replication was assessed in GHS (P<3.9×10−6 correcting for 12,808 gene expressions).

For Stranger et al [1], data were extracted from Table S2. We considered as significant the associations found in at least 3 HAPMAP populations. For Dixon et al [2], data were extracted from Table S1 and trans eQTLs were excluded. Matching of probes was done using a table provided by the authors on their web site. For Schadt et al [3], cis eQTLs considered significant (First.Pass.Indicator set to 1) were extracted from Table S3. For each eQTL, we selected in GHS the P-value of the best cis eSNP. The full data used to generate this table are provided in Files S2–S4.

Figure 2. Comparison of the distributions of P-values of cis eQTLs reported as significant in three previous association studies with P-values observed in GHS for the same eQTLs.

For each of the 3 comparisons, we selected in GHS the subset of gene expressions claimed as significant in the study of comparison. Only autosomal genes were considered in these comparisons. The data used to generate this figure are provided in Files S2–S4. See also footnote of Table S3 for details.

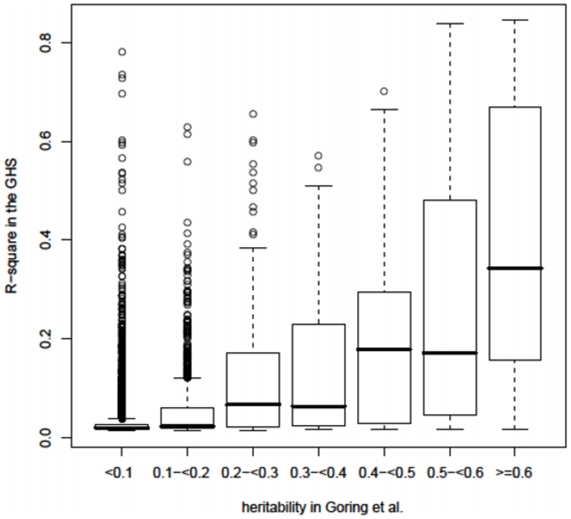

We also examined the overlap between cis eQTLs in GHS and cis-heritable eQTLs found by expression profiling of lymphocyte RNA in the San Antonio Family Heart Study (SAFHS) 4. Among the eQTLs with a cis heritability ≥0.1 in SAFHS, 62% were significantly cis modulated in GHS, and this proportion reached 89% for heritabilities ≥0.6 ( Figure 3 , File S5).

Figure 3. Comparison of the heritability of cis eQTLs estimated in the SAFHS study with the R2 of the corresponding cis eQTLs in GHS.

Data were extracted from Supplementary Table 4 in Göring et al. [4] and comparisons were restricted to genes having a corresponding gene symbol in GHS. Heritability in the SAFHS was estimated by linkage analysis and accounts for the whole variability at a locus while R2 refers to a single eSNP (the best eSNP) and therefore underestimates the global variability affecting gene expression at a locus. The data used to generate this figure are provided in File S5. The median R2 was globally lower than the heritability, consistent with the fact that the R2 is referring to a single SNP whereas heritability reflects the whole genetic variation at a locus.

Trans associations showed much weaker consistency across studies. Among the 50 eQTLs having a trans lod score >4.0 in SAFHS [4] with corresponding expression detected in GHS, only one, MAPK8IP1, was replicated in GHS (P<10−300). Replication of the trans associations in studies of similar power as the present one would be of interest.

Identifying eQTLs that may result from the presence of SNPs in probe sequences

For all probes present on the Illumina HT12 array, a systematic search for sequence polymorphisms was undertaken, using the HapMap database as reference (Release 27; Phase II+III, Feb09, on NCBI B36 assembly and dbSNP b126). Among the 2,477 genes whose expression was associated with cis eSNPs, 173 (7%) were probed by one or several polymorphic sequences (180 probes) (Table S1). For 32 of these probes, the HapMap SNP was present on the Affymetrix array used in this study and for 41 other probes, the HapMap SNP had one or several perfect proxies on the array. For those eQTLs, we cannot exclude the possibility of an artefactual association due to a differential binding of the probe to its target sequence.

Gene expression, a link between DNA sequence variability and clinical phenotypes?

A link between genetic variability and clinical phenotypes is supported in human studies by several observations relating variants in regulatory gene regions to protein phenotypes or diseases [19], [20]. However, this message-passing paradigm has never been evaluated on a genome-wide basis. We therefore tested whether monocytes gene expression might mediate the effects of loci recently identified by GWAS of cardiovascular risk factors. For each locus identified in GWAS of lipid variables [21], blood pressure (BP) [22] and body mass index (BMI) [23], we selected the lead SNP or a tag SNP having an r2≥0.8 with the lead SNP in GHS data. Associations between lead/tag SNPs and corresponding risk factors were checked in all GHS subjects for whom genome-wide data was available (n = 3,175). Most previous GWAS loci for circulating lipids were replicated in our data ( Table 4 ) but only few of the findings of GWAS of BMI and BP were replicated (Table S2). This low replication is probably due to a lack of power, as the maximum R2 observed in the GWAS of BP [22] was 0.09% and the power of GHS to replicate such an association was only 38%.

Table 4. Loci identified in GWAS of circulating lipids – associations of lead/tag SNPs with phenotypes and expression, and of expression with phenotype in GHS.

| Lead SNP in GWAS | Phenotype | Chr | Position (Mb) | Genes in region | Tag SNP in Affy 6.0 with r2>0.8 | r2 between lead SNP and tag SNP | Association between tag SNP and phenotype (P-value) | eQTL associated with tag SNP | Association between tag SNP and eQTL (P-value) | Association between eQTL and phenotype (P-value) |

| rs10889353 | TG | 1 | 62.83 | DOCK7 | rs10889353 | 1.00 | 1.86E-04 | DOCK7 | 7.09E-52 | 0.3970 |

| rs646776 * | LDL | 1 | 109.53 | CELSR2/PSRC1/SORT1 | rs629301 | 1.00 | 2.62E-04 | PSRC1 | 2.34E-56 | 0.0190 |

| CELSR2 | 7.56E-06 | 0.6195 | ||||||||

| rs693 | LDL | 2 | 21.14 | APOB | rs693 | 1.00 | 1.61E-04 | none | ||

| rs6754295 | HDL | 2 | 21.12 | APOB | rs673548 | 0.86 | 0.0435 | none | ||

| rs673548 | TG | 2 | 21.15 | APOB | rs673548 | 1.00 | 4.10E-05 | none | ||

| rs780094 | TG | 2 | 27.65 | GCKR | rs780094 | 1.00 | 3.15E-08 | none | ||

| rs6756629 | LDL | 2 | 43.98 | ABCG5 | rs4953023 | 1.00 | 7.87E-05 | none | ||

| rs3846662 | LDL | 5 | 74.69 | HMGCR | rs12654264 | 0.84 | 9.26E-06 | none | ||

| rs12670798 | LDL | 7 | 21.38 | DNAH11 | none | |||||

| rs2240466 | TG | 7 | 72.3 | MLXIPL | rs2074755 | 1.00 | 0.0015 | none | ||

| rs2083637 | HDL | 8 | 19.91 | LPL | rs17489282 | 1.00 | 5.91E-05 | LPL | 2.18E-06 | 0.0006 |

| rs2083637 | TG | 8 | 19.91 | LPL | rs17489282 | 1.00 | 3.31E-07 | LPL | 2.18E-06 | 0.3520 |

| rs3905000 | HDL | 9 | 104.74 | ABCA1 | rs3890182 | 1.00 | 0.33 | none | ||

| rs7395662 | HDL | 11 | 48.48 | MADD-FOLH1 | rs7395662 | 1.00 | 0.17 | MYBPC3 | 1.17E-09 | 0.1435 |

| SPI1 | 4.42E-06 | 0.0222 | ||||||||

| rs174570 | LDL | 11 | 61.35 | FADS2/3 | rs174570 | 1.00 | 0.0386 | none | ||

| rs12272004 | TG | 11 | 116.11 | APO(A1/A4/A5/C3) | rs10488699 | 1.00 | 1.63E-06 | none | ||

| rs1532085 | HDL | 15 | 56.47 | LIPC | none | |||||

| rs1532624 | HDL | 16 | 55.56 | CETP | none | |||||

| rs2271293 | HDL | 16 | 66.46 | CTCF-PRMT8 | rs2271293 | 1.00 | 0.0145 | DPEP3 | 5.09E-17 | 0.8275 |

| DUS2L | 5.15E-42 | 0.1410 | ||||||||

| GFOD2 | 1.48E-17 | 0.6400 | ||||||||

| LCAT | 6.00E-06 | 0.3347 | ||||||||

| PARD6A | 7.88E-07 | 0.8772 | ||||||||

| PRMT7 | 2.03E-06 | 0.1690 | ||||||||

| rs4939883 | HDL | 18 | 45.42 | LIPG | rs7240405 | 1.00 | 0.0233 | none | ||

| rs2228671 | LDL | 19 | 11.07 | LDLR | none | |||||

| rs157580 | LDL | 19 | 50.09 | TOMM40-APOE | none |

GWAS loci were taken from Table 2 in ref. 21.

*This SNP was also found in GWAS of CAD. The association between tag SNP and phenotype was tested in the 3,175 GHS subjects having GWV data. Association between eQTL and tag SNP or phenotype was tested in the 1,490 GHS subjects having GWE data. In bold are shown the loci for which the SNP-phenotype association found in GWAS is compatible with mediation by gene expression. Similar analyses for BMI and BP are given in Table S2.

For each GWAS locus, we examined whether the lead/tag SNP correlated with any expression trait in GHS data and when a significant association was found, we checked whether the expression trait was significantly associated with the risk factor under consideration. This analysis revealed that very few GWAS results were compatible with an effect mediated by gene expression at the locus ( Table 4 and Table S2). There were, however, two exceptions: the first one concerned the LPL locus, where the minor allele of rs17489282 was associated with higher HDL-cholesterol (P = 5.91×10−5) and LPL expression (P = 2.18×10−6), while HDL-cholesterol and LPL expression were positively correlated (P = 6×10−4), consistent with an effect mediated by LPL; the second one concerned the association between the 1p13.3 locus and LDL-cholesterol. This locus encompasses three potential candidate genes, CELSR2, PSRC1 and SORT1, and it has been suggested that CELSR2 or SORT1 could be responsible for the reported associations of this locus with LDL [3], [24], [25]. In our data, the minor allele of rs629301 (a perfect tag of the lead SNP identified by GWAS), was associated with lower LDL-cholesterol (P = 2.6×10−4) and higher PRSC1 expression (P = 2.3×10−56) while PRSC1 expression and LDL-cholesterol were negatively correlated (P = 0.019). Results for CELSR2 were much less consistent and SORT1, the third gene at the locus, was not cis-modulated in monocytes.

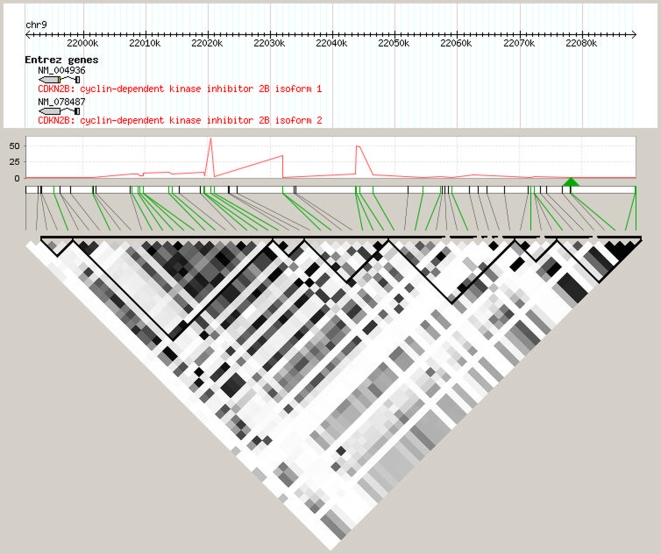

Several loci associated with coronary artery disease (CAD) have been identified by GWAS [26]–[29]. The strongest association involves SNPs in the 9p21 region. Recently it was reported that deletion in mice of the region orthologous to the 9p21 CAD interval in human affects the expression of the nearby cdkn2a and cdkn2b genes as well as the properties of proliferation of vascular cells [30]. The Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor coding genes, CDNK2A and CDNK2B, are also located close to the CAD locus in humans. CDKN2A expression in monocytes was not detected in our study, we therefore focused our analysis on CDKN2B. All SNPs available in GHS in the region encompassing the CAD locus were tested for association with the expression of CDKN2B. Figure 4 shows that CDKN2B expression was strongly associated with several SNPs located in a region upstream of the gene sequence (P<10−60). However, these SNPs were not associated with CAD (this result was obtained in a yet unpublished GWAS comparing GHS individuals to a cohort of CAD patients), whereas proxies of the CAD-associated SNPs were unrelated with CDKN2B expression (see legend of Figure 4 for more details). The SNPs associated with CDKN2B expression are located within the sequence of the non-coding alternatively spliced gene ANRIL (also named CDKN2BAS) whose implication in the association with CAD has been hypothesized [31]. Although our results are limited by the fact that neither CDKN2A nor ANRIL expressions could be evaluated, they reveal that in humans, SNPs that affect CDKN2B expression are different from those that are known to affect CAD risk ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 4. The loci affecting CDKN2B expression and CAD on chromosome 9p21 are independent.

The lead SNP rs1333049 generally reported at the CAD locus was not present on the Affymetrix 6.0 array, we therefore selected its best proxy, rs10757272 (position 22078260, r2 = 0.9 with rs1333049), using SNAP (https://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/snap). Positions of genotyped SNPs are shown using a green link and position of the proxy SNP, rs10757272, is represented by a green triangle. The red curve reflect the –log10(P-value) for the association between SNPs and CDKN2B expression. The LD (r2) between pairs of SNPs is shown at the bottom of the figure using a range of colors between white (r2 = 0) and black (r2 = 1). The CDKN2B and CAD-associated SNPs are located in different blocks of LD strongly suggesting that the genetic effects on CDKN2B expression and CAD are independent.

Expression traits associated with risk factors

To investigate gene expression in relation to risk factors (age, gender, BMI, HDL and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, Systolic and Diastolic Blood pressure, smoking and plasma CRP), the study-wise significance threshold was set at 3.9×10−7 to correct for the number of risk factors (n = 10) and expressions (n = 12,808) tested. Overall, 1,662 expression traits (13.0%) were associated with at least one risk factor ( Table 5 and File S6). Gender and age were the two major factors influencing expression levels (807 gene expressions were affected by gender and 396 by age). BMI, smoking and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were also correlated with numerous expression traits (230, 294 and 328, respectively). Conversely, few associations with BP and lipids were observed ( Table 5 ).

Table 5. Number of expression traits associated with risk factors and cis eSNPs.

| Risk factor | Number of expression traits associated with the specified risk factor | Number (%) of expression traits also associated with cis eSNPs | Odds ratio (95% CI)* |

| Gender | 807 | 230 (28.5%) | 1.73 (1.47–2.03) |

| Age | 396 | 94 (23.7%) | 1.31 (1.03–1.66) |

| BMI | 230 | 72 (31.3%) | 1.92 (1.45–2.56) |

| HDL | 9 | 1 (11.1%) | ND |

| LDL | 1 | 0 | ND |

| Triglycerides | 9 | 3 (33.3%) | ND |

| SBP | 48 | 6 (12.5%) | 0.59 (0.25–1.40) |

| DBP | 18 | 2 (11.1%) | ND |

| Smoking | 294 | 126 (42.9%) | 3.24 (2.56–4.10) |

| CRP | 328 | 116 (35.4%) | 2.34 (1.86–2.95) |

| All (irrespective of any association with risk factor) | 12,808 | 2,477 (19.3%) |

Study-wise levels of significance were considered for associations of expression traits with risk factors and SNPs (3.9×10−7 and 5.78×10−12, respectively). Associations of expression traits with BMI, CRP and smoking were adjusted for age and sex, and association with HDL, LDL, triglycerides, SBP and DBP were additionally adjusted for BMI.

*Odds ratio (OR) of being influenced by a cis eSNP for an expression trait associated with a given risk factor. For example, gender-related expression traits have an OR of 1.73 of being influenced by cis eSNPs by comparison to expression traits unrelated to gender. ND: not determined because of small numbers.

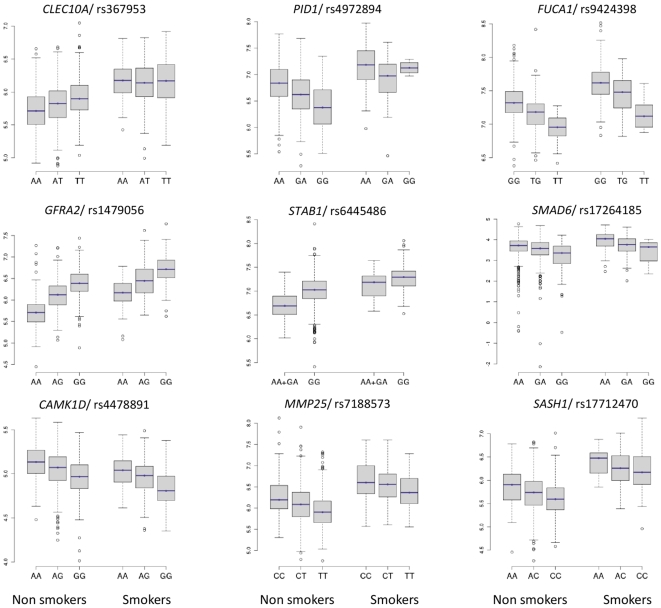

Genetic and non-genetic factors act additively on gene expression

Cis eQTLs were over-represented among expression traits that were also affected by gender, age, BMI, smoking and CRP, with odds ratios as high as 3.24 for cigarette smoking ( Table 5 ). This suggests that some genes are more responsive than others to the influence of multiple factors. For expression traits that were simultaneously associated with cis eSNPs and risk factors (n = 465), we determined the joint effects of the two sources of variability on expression level. For this purpose, each eQTL was modelled as a function of the best cis-acting eSNP, the associated risk factor and the interaction between the two. When several risk factors were associated with the same eQTL, each of them was tested separately for interaction with the corresponding SNP. The best FDR-corrected P-values for interaction (File S7) were 0.014 (ISCU expression, gender and rs4830487) and the second one was 0.042 (HIST1H2AE expression, smoking and rs16891378). This first genome-wide exploration of interaction between cis eSNPs and risk factors on gene expression therefore suggests that the two sources of variability mostly act additively on expression. This is illustrated for eQTLs affected by smoking in Figure 5 . It must be noted however that despite the large size of this study, its power may nevertheless be insufficient to assess weak interaction.

Figure 5. Effect of the best cis eSNP and smoking on expression of smoking-related eQTLs.

The proportion of variability of expression explained by the best cis eSNP varied from 3.1% for CLEC10A to 27.2% for GFRA2 while the proportion explained by smoking varied from 2.8% for SMAD6 to 21.6% for SASH1. The lowest P-value for interaction between SNP and smoking was 0.02 for STAB1.

Expressions influenced by genetic and risk factors are enriched in immunity and defense genes

An ontology analysis using the Panther system demonstrated that, by reference to the list of 12,808 genes expressed in monocytes, the set of 465 expression traits affected by multiple sources of variability was enriched in “Immunity and defense” genes (69 observed/35.8 expected, P = 4.5×10−6), especially in the sub-categories of “Macrophage-mediated immunity” (18/3.6, P = 7.5×10−6).

The variability of each risk factor can be characterized by a limited set of independent gene expressions

The preceding analyses revealed that each risk factor was associated with a large number of expression traits, thus emphasizing the multiple inter-relations existing between the transcriptomic and risk factor profiles of an individual. While it is important from a biological and mechanistic perspective to characterize at best all the genes that are influenced by a given condition, from a clinical perspective, it might be more relevant to identify a limited set of gene expressions that could efficiently discriminate individuals with different risk profiles. Indeed, because of the tight co-regulation of genes within biological systems, numerous gene expressions are inter-correlated and consequently, their association with risk factors are not independent. To account for this inter-dependency, we conducted a multivariate analysis to identify expression traits that were independently associated with each risk factor.

To obtain reliable results, we randomly divided the study population into two sub-samples of equal size which were used for screening and validation purposes respectively (see Materials and Methods). In these analyses, each risk factor was considered separately whereas all expression traits were envisaged jointly for their potential association with the risk factor, considered here as the dependent variable. The screening/validation procedure was repeated 250 times and for each risk factor, we report expression traits associated (P<0.01) with the risk factor in more than 25% of the replicates. This stringent approach led to the identification of 106 independent expression correlates for the ten risk factors ( Table 6 ), a much reduced number compared to the 1,662 expression traits previously identified by the one-to-one association analysis presented in Table 5 .

Table 6. Subsets of expression traits showing robust independent association with the different risk factors in the validation sample.

| Risk factor | Median (range) of the global P-values across replicates* | List of gene expressions associated with risk factor after adjustment on covariates$ |

| Gender# | All P<10−100 | CCDC106, MMEL1, ANKRD57, CXCR7, FCGR2B, SOX15, FCGBP, LPXN, CD24, HOXA9, PTK6, DDX43, RAB11FIP1, PTK2, CLEC4G, ADARB1, PROK2, MYBPH, PER3, TPPP3, MPO, FAM24B, EMR3, ENOSF1, TPM2, PTTG1IP, CELSR3, CD1A, FOLR2, BOLA3, OPLAH |

| Age | 1.1×10−50(2.9×10−70–3.6×10−37) | PARP3, PDGFRB, NEFH, P2RY2, SPINK2, GPER, NFKBIZ, ZSCAN18, IGLL1, BLK, ITM2C, C1RL |

| BMI | 1.5×10−37(2.6×10−50–2.7×10−26) | CX3CR1, MAP3K6, FCGBP, CD209, LYPD2, VSIG4, RPGRIP1, PACAP, LGALS3BP, ELA2, CD36, ABCA1 |

| HDL-chol | 5.5×10−10(2.2×10−15–2.7×10−3) | PRDM1, SCD, DPEP2,TMEM43 |

| LDL-chol | 2.3×10−3(3.8×10−7–0.5) | BYSL, ABCA1 |

| Triglycerides | 4.2×10−6(2.1×10−11–0.08) | MYLIP, PHGDH, ABCA1, ELA2, ABCG1, SASH1 |

| SBP | 5.0×10−20(4.6×10−27–2.6×10−12) | CRIP1, GFOD1, DHRS9, NR4A2, TSC22D3, ARID5B, PAPSS2, HVCN1 |

| DBP | 1.8×10−10(3.6×10−16–1.2×10−4) | GFOD1, CRIP1, TPPP3, NR4A2,EMP1 |

| CRP | 6.1×10−51(7.3×10−67–2.0×10−30) | FAM20A, CETP, FCGBP, COL9A2, C1RL, ADM, CREB5, APBB1IP, CX3CR1, C1QB, MS4A4A, FCER1A, ALDH1A1, FLVCR2 |

| Smoking | 9.7×10−108(1.9×10−128–3.7×10−84) | SASH1, P2RY6, PTGDS, PID1, CYP4F22, MMP25, WWC3, FUCA1, PDE4B, STAB1, GFRA2, CLEC10A, CAMK1D, DHRS9, CNTNAP2, IQCK, ITGB7, SMAD6, |

*The global P-value is the P-value obtained by comparing the model with all significant expression traits and covariates to the model with covariates only.

Expressions that are underlined are associated negatively to the risk factor (or to male gender), others are associated positively (or to female gender).

Covariates: age and gender for BMI, CRP and smoking; age, gender and BMI for lipids and BP.

Gender-associated traits were selected from autosomal genes only.

Gender and age

Even after exclusion of sex-linked genes, gender was independently associated with the largest number of expression traits (n = 31) which, considered all together, contributed to a highly significant discrimination between males and females (P<10−100). By contrast the number of expression traits independently associated with age was more limited (n = 12).

BMI and CRP

Both factors were independently associated with 12 and 14 expression traits respectively. Inspection of the genes listed in Table 6 shows that several of them, including CX3CR1, CD209, CLEC10A, FCER1A, FCGBP, C1RL, C1QB, CD36, ADM and VSIG4, encode proteins involved in the differentiation or maturation of immunity-related cells and in host defence [32]–[38]. We may speculate that the variability of expression of these genes is the consequence of an already present heterogeneity of monocytes [39], [40] or reflects a particular transcription pattern that prefigures future functional changes. The example of CX3CR1 which was positively associated with both BMI and CRP is particularly interesting as this gene encodes the fractalkine receptor whose role is essential in the migration of monocytes to sites of inflammation and injury, especially in atherosclerotic lesions [41].

Lipids

ABCA1 and ABCG1 gene expressions were both associated with circulating lipids. The proteins encoded by these genes are key players in reverse cholesterol transport and the regulation of lipid-trafficking mechanisms in macrophages respectively [42], [43]. MYLIP (Idol) is a ligase involved in the ubiquitination and degradation of LDL receptors [44], [45] and SCD is a stearoyl-CoA desaturase involved in the conversion of saturated into monounsaturated fatty acids that regulates lipid metabolism and may be modulated by dietary intake [46].

Blood pressure

One of the main independent correlates of SBP was ARID5B (MRF2), whose relevance in the physiology of BP regulation is supported by its role as a regulator of smooth muscle differentiation and proliferation [47]. GFOD1, another expression correlate of SBP and DBP is a gene of unknown function which has been associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [48].

Cigarette smoking has a major impact on gene expression and atherosclerosis

Smoking was independently associated with 18 expression traits ( Table 6 ) which, considered all together, contributed to a highly significant discrimination between smokers and non smokers (P<10−107, R2>50%). Nine of these genes were modulated by cis eSNPs ( Table 7 ) and as already mentioned above, the genetic and smoking effects on these gene expressions were additive ( Figure 5 ).

Table 7. Smoking-related expression traits: association of expression with cis-acting eSNP, smoking and extent of atherosclerosis.

| Smoking-related gene expressions | Association of the best cis eSNP with expression | Association of the best cis eSNP with the extent of atherosclerosis | Association of expression with smoking | Association of expression with the extent of atherosclerosis | ||||

| SNP number | P-value | t- value | P-value | t- value | P-value | t- value | P-value | |

| CAMK1D | rs4478891 | 1.1×10−26 | 0.7 | 0.51 | −7.4 | 2.3×10−13 | −3.1 | 0.002 |

| CLEC10A | rs367953 | 3.6×10−12 | 0.5 | 0.65 | 13.0 | 5.4×10−37 | −0.4 | 0.68 |

| CNTNAP2 | rs1110144 | 8.6×10−12 | −1.1 | 0.28 | 6.5 | 7.3×10−11 | 1.7 | 0.082 |

| CYP4F22 | rs11253478 | 1.5×10−6 | 0.0 | 1.00 | −17.5 | 1.8×10−62 | −2.2 | 0.027 |

| DHRS9 | rs1386426 | 4.3×10−7 | 2.5 | 0.012 | −6.3 | 3.5×10−10 | 0.2 | 0.82 |

| FUCA1 | rs9424398 | 6.8×10−42 | 1.0 | 0.34 | 13.7 | 1.4×10−40 | 2.1 | 0.035 |

| GFRA2 | rs1479056 | 1.6×10−108 | 0.5 | 0.62 | 13.3 | 3.1×10−38 | 0.8 | 0.44 |

| IQCK | rs1879894 | 1.1×10−7 | 0.6 | 0.52 | −7.6 | 2.7×10−14 | −1.7 | 0.089 |

| ITGB7 | rs17080239 | 1.0×10−6 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 6.3 | 3.9×10−10 | 0.3 | 0.73 |

| MMP25 | rs7188573 | 4.7×10−18 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 15.6 | 5.4×10−51 | 3.6 | 3.51×10−4 |

| P2RY6 | rs3781305 | 9.0×10−7 | −1.0 | 0.34 | 16.0 | 1.5×10−53 | 0.5 | 0.58 |

| PDE4B | rs4352802 | 4.5×10−7 | −1.2 | 0.24 | −7.7 | 1.2×10−14 | −1.8 | 0.077 |

| PID1 | rs4972894 | 1.1×10−25 | −0.1 | 0.95 | 10.5 | 6.2×10−25 | 1.4 | 0.16 |

| PTGDS | rs10870158 | 6.0×10−9 | 0.7 | 0.49 | −14.0 | 3.5×10−42 | −5.2 | 1.77×10−7 |

| SASH1 | rs17712470 | 5.6×10−14 | 0.5 | 0.63 | 20.5 | 5.1×10−83 | 4.4 | 1.38×10−5 |

| SMAD6 | rs17264185 | 2.7×10−15 | −1.5 | 0.13 | 6.8 | 9.6×10−12 | 1.6 | 0.11 |

| STAB1 | rs9867823 | 2.8×10−28 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 12.3 | 2.9×10−33 | 0.7 | 0.50 |

| WWC3 | rs1013478 | 8.0×10−6 | −1.1 | 0.26 | 10.6 | 1.8×10−25 | 3.4 | 6.32×10−4 |

Atherosclerosis was assessed by the number of carotid plaques.

Associations of expressions with smoking and number of carotid plaques were adjusted on gender and age. Cis eSNPs significant at a study-wise level (P<5.78×10−12) and associations with carotid plaques significant after correction for multiple testing (n = 18 tests) are shown in bold characters.

Among the 18 expression traits associated with smoking, SASH1, P2RY6 and PTGDS were systematically retrieved in all screening/validation replicates (Table S3). SASH1 is a tumor suppressor gene [49], P2RY6 encodes a G-protein-coupled receptor involved in the proinflammatory response to UDP in monocytes [50] and PTGDS encodes a prostaglandin D synthase involved in smooth muscle contraction/relaxation and inhibition of platelet aggregation, two functions known to be modified by tobacco consumption. Recently, in a GWE study of leukocytes RNA, PTGDS and SASH1 expressions were found associated with cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine used as a marker of tobacco exposure [51].

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for atherosclerosis [52]. In GHS participants, the prevalence of atherosclerotic plaques in the right and left carotid arteries, assessed by echography, was strongly increased in smokers (P = 9.1×10−7 after adjustment for age and gender). Among the 18 gene expressions independently associated with smoking, four were individually correlated with the number of carotid plaques, PTGDS (P = 1.8×10−7) negatively and MMP25 (P = 3.5×10−4), SASH1 (P = 1.4×10−5) and WWC3 (P = 6.3×10−4) positively ( Table 7 ). In a multivariate model including the four expression traits and smoking, as well as age and gender, PTGDS (P = 5.7×10−4) and SASH1 (P = 0.012) remained significantly associated with the number of plaques whereas MMP25 (P = 0.09), WWC3 (P = 0.10) and smoking (P = 0.5) were no longer significant, suggesting that the association between smoking and atherosclerosis was mostly reflected (or mediated) by its effect on the expression of these four genes. The fact that PTGDS and SASH1 expression remained associated with carotid plaques after adjustment on smoking status may indicate a broader implication of these genes in atherosclerosis than the sole effect induced by smoking. However it is also possible that the expression of these two genes more faithfully reflects tobacco consumption than the dichotomous variable used to define smoking. This illustrates the dual aspect of the transcriptome which may be viewed either as an element in a causal chain or as reflecting ongoing processes with no implied causation. Because genetics may help to dissect causal pathways, we examined whether the best cis eSNPs associated with expression of the smoking-related genes were also associated with carotid atherosclerosis, but no such association was detected (Table 7).

Discussion

This large-scale investigation of the transcriptome of monocytes in healthy individuals provides new biological insights into the mechanisms by which gene expression might contribute to disease pathogenesis. In the line of previous studies [1]–[5], we could build a detailed map of cis-regulated eQTLs in monocytes. Even if cell-specific eQTLs exist [53], a large fraction of them are likely to be common to other cell types, and the eQTL map provided here constitutes the most extensive one so far.

Despite the large number of eQTLs identified, the transcriptome of circulating monocytes, contrary to initial expectations [7]–[10], appeared of modest help to dissect the relationship between genome variability and complex human traits such as cardiovascular risk factors. One explanation for this finding might be that monocytes are not the most relevant cells for unravelling links between genome variation and the risk factors investigated. With regard to circulating lipids for example, only 28 of the 45 genes located in regions harbouring SNPs associated with circulating lipids in GWAS [24] were expressed in monocytes. The difficulty to corroborate the messenger paradigm in human clinical studies may also relate to the fact that the linear model of causality generally assumed to reflect the relation between genome variability, expression and phenotype may be too simplistic to account for a much more complex biological reality. The effects of genetic variants may be too weak to allow detection even in a study of this size. It is also important to keep in mind that most reported eSNPs are acting in cis, whereas trans eSNPs may actually be those that mainly drive the changes in gene expression that affect disease risk.

Most importantly, the present study highlighted for the first time the strong link existing between the transcriptome of an individual and his (her) clinical and epidemiological profile. The fact that the transcriptome tightly mirrors the variability of risk factors at a cellular level may have profound implications from a biological and clinical perspective. Until now, the traditional way of viewing the role of genes in the susceptibility to human diseases was through the effect of their variability of sequence. The present findings suggest that another important, if not greater, impact of genes on human phenotypes relates to the variability of their expression, whatever the origin of this variability. The global association observed between most cardiovascular risk factors and the transcriptome and the fact that each risk factor could be characterized by a limited and specific set of independent gene expressions further suggests that this relationship might be clinically relevant. This was particularly well illustrated by the response of the transcriptome to cigarette smoking. We showed that less than 20 genes among the 12,000 expressed in monocytes could highly discriminate smokers and non-smokers, and among them, four genes were sufficient to account for the strong association existing between smoking and atherosclerosis. Whether these genes are causally involved in the mechanisms linking smoking to the development of atherosclerotic plaques or whether they are only markers of ongoing pathological processes remains to be elucidated.

In conclusion, the variability of the transcriptome of monocytes can be viewed from two perspectives. On one hand it reflects the accumulation of effects originating from the genome and the environment and may inform on a number of ongoing processes relevant to disease. On the other hand, it may reflect or anticipate differences in monocytes biology that could have pathophysiological implications. This dual perspective suggests that a better understanding of the sources of variability of the transcriptome of monocytes and other easily accessible cells, will contribute in an important way to our understanding of complex diseases.

Materials and Methods

Ethic statement

The study protocol and drawing of the blood sample have been approved by the local ethics committee and by the local and federal data safety commissioners (Ethik-Kommission der Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz). All subjects included signed an informed consent.

Study population

The Gutenberg Heart Study (GHS) is designed as a community-based, prospective, observational single-center cohort study in the Rhein-Main region in western mid-Germany. The primary aim of the study is to improve the individual cardiovascular risk prediction by identifying genetic and non genetic risk factors contributing to cardiovascular diseases, with a strong emphasis on atherosclerosis.

A sample of eligible participants was randomly drawn from the registers of the local registry offices in the city of Mainz and the district of Mainz-Bingen. This sample was stratified in a ratio of 1∶1 for gender and residence, and in equal numbers for decades of age. Inclusion criteria were an age between 35 and 74 years and a written consent; exclusion criteria were insufficient knowledge of the German language to understand explanations and instructions, and physical or psychic inability to participate in the examinations in the study center. Individuals were invited for a 5-hour baseline-examination to the study center where clinical examinations and collection of blood samples were performed. The present analysis was based on an initial sample of 3,336 subjects successively enrolled into the GHS from April 2007 to April 2008. Genomic DNA was isolated from all participants. Monocyte RNA was isolated from half of the participants recruited each day to ensure rapid sample processing and isolation of total RNA. For approximately 1,500 study participants, both DNA and RNA were available.

Measurement and definition of cardiovascular risk factors

Blood pressure measurements were performed by an automated sphygmomanometer blood pressure meter (Omron 705CP-II, OMRON Medizintechnik Handesgesellschaft GmbH, Germany) after 5, 8 and 11 minutes of rest. The mean from the 2nd and 3rd standardized measurement was calculated for the systolic and diastolic blood pressure. For the anthropometric measurements, calibrated, digital scales (Seca 862, Seca Germany), a measuring stick (Seca 220, Seca, Germany) and a waist measuring tape were used. The blood sampling was carried out under fasting conditions. HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and C-reactive protein (CRP) measurements were performed on an Architect c8000 by commercially available tests (CRP, Ultra HDL, Direct LDL and Triglycerides) from Abbott (www.abbottdiagnostics.de). All tests were measured under standardized conditions in an accredited laboratory of the institute of clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine at the University of Mainz. Smoking was defined by dichotomizing the population into non-smokers (never smokers and former smokers) and smokers (occasional smoker, i.e. <1 cigarette/day, and smoker, i.e. >1 cigarette/day).

Ultrasound of the Carotid Arteries and evaluation of the number of atherosclerotic plaques

IMT was assessed with an ie33 ultrasound system (Philips, NL) using an 11 to 3 MHz linear array transducer. Experienced technologists blinded to participants' clinical data made all ultrasound measurements. The IMT was visualized bilaterally at the far wall of the CCA. In brief, a cursor representing the region of interest (10 mm) was positioned 1 cm in front of the beginning before the carotid bulb. Evaluation was performed using an automatic computerized system (Philips, NL Qlab software) and triggering was performed according to the Q wave of the ECG to enable measurement in complete relaxation of the ventricle. IMT was recorded 1 cm before the carotid bulb in a part without plaque on the left and right side. As mean IMT, the CCA was reported with the sum of IMT of the left and right side and afterwards divided by two. Plaques were defined as thickening of the IMT of at least 1.5 mm and presence was checked in all measured arteries. The number of plaques from both sides was recorded and subjects being classified as plaque positive when at least one plaque was measured on either side or plaque negative, when no plaque was recorded.

Genotyping

For each participant genomic DNA was extracted from buffy-coats prepared from EDTA blood samples (9 mL) using the method of Miller [54]. Genotyping was performed using the Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (http://www.affymetrix.com), as described by the Affymetrix user manual. Genotypes were called using the Affymetrix Birdseed-V2 calling algorithm and quality control was performed using GenABEL (http://mga.bionet.nsc.ru/nlru/GenABEL/). Individuals with a call rate below 97% or a too high autosomal heterozygosity (False Discovery Rate <1%) were excluded. After applying standard quality criteria (minor allele frequency >1%, genotype call rate >98% and P-value of deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium >10−4), 675,350 out of 900,392 SNPs remained for analysis.

Separation of monocytes

Separation of monocytes was conducted within 60 min after blood collection and RNA was extracted the same day. Total RNA was isolated from monocytes using Trizol extraction and purification by silica-based columns. To separate monocytes, 8 mL blood was collected using the Vacutainer CPT Cell Preparation Tube System (BD, Heidelberg, Germany) and 400 µL Rosette Sep Monocyte Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) was added immediately after blood collection. Monocytes, not labeled by antibodies, are collected as a highly enriched fraction at the interface between plasma and the density medium in the tube. After separation, cells were washed twice in ice cold PBS buffer containing 2 mM EDTA. Success of monocyte separation was controlled using an ADVIA 2120 Analyser (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Eschborn, Germany) for part of the samples.

Preparation of RNA

After separation, cells were resuspended in 1.5 mL Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) immediately and frozen at −20°C until isolation of RNA at the same day (maximal storage time 5 h). After thawing, samples were transferred into Phase Lock Gel Tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), 200 mL chloroform was added and phases were separated by centrifugation at 4600 rpm for 15 min. Purification of total monocytes RNA was performed using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufactures' Animal Cell Spin and RNA Cleanup protocols including an additional DNase digestion step. Total RNA was eluted in 20 µL RNase-free water. Yield of RNA was checked spectrophotometrically by NanoDrop N-1000 measuring the OD260 as well as the ratio OD260 and OD280. The integrity of the total RNA was assessed through analysis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Boeblingen, Germany).

Genome-Wide Expression analysis

GWE analysis was performed on monocytes RNA samples using the Illumina HT-12 v3 BeadChip (http://www.Illumina.com). RNA samples were processed in batches of 96 samples. Two hundred ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed, amplified and biotinylated using the Illumina TotalPrep-96 RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion/Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). 700 ng of each biotinylated cRNA was hybridized to a single BeadChip at 58°C for 16–18 hours. BeadChips were scanned using the Illumina Bead Array Reader.

Pre-processing of expression data

The summary probe-level data delivered by the Illumina scanner (mean and SD computed over all beads for a particular probe) was loaded in Beadstudio. The pre-processing done by the Illumina software, at the level of the scanner and by Beadstudio included: correction for local background effects, removal of outlier beads, computation of average bead signal and SD for each probe and gene, calculation of detection P-values using negative controls present on the array, quantile normalization across arrays, check of outlier samples using a clustering algorithm, check of positive controls. Analyses were carried out on the mean level for all probes in each gene. To stabilise variance across expression levels, we applied an arcsinh transformation to the expression data [55]. Compared to a log transformation, this transformation has the advantage not to discard negative expression values which can occur in Illumina data.

The Illumina HT-12 BeadChip included 37,804 genes (some probes being not assigned to RefSeq genes). A gene was declared significantly expressed in the dataset, i.e. expressed above background (as measured by the negative controls present on each array), when the detection P-value calculated by Beadstudio was <0.05 in more that 5% of the samples. This resulted in 22,305 genes considered as being significantly expressed in our dataset. After removing 8,058 putative and/or non well characterized genes, i.e. gene names starting by KIAA (n = 165), FLJ (n = 214), HS (n = 4,262), Cxorf (n = 842), MGC (n = 72), LOC (n = 2,503), 12,808 well characterized detected genes remained for analysis.

Genome wide association analysis

To test all associations between SNPs and expressions in a reasonable amount of time, a C script calling the GNU Scientific Library (GSL) “TAMU ANOVA” (www.stat.tamu.edu/~aredd/tamuanova/) was written. For all significant associations, results were checked against the R-lm library [56]. When the numbers of homozygotes for the minor allele of a SNP was lower than 30, they were grouped with heterozygotes. We used a family-wise error rate of 0.05 corrected for the number of tested SNP x expression associations, which corresponds to declare significant any association with a P-value <5.78×10−12. To increase robustness, associations significant by ANOVA were further checked by a Kruskall-Wallis (KW) test and only associations with a P-value <10−10 by the KW test were retained. P-values given in the results and in the GHS-Express database are those obtained by ANOVA. For SNPs on chromosome X, associations with gene expression were assessed separately in women and men and the P-values were combined using the Fisher method [57].

Association of gene expressions with CVD risk factors

The relationship between gene expression and each CHD risk factor was tested by a linear regression model using R-lm, with gene expression as the dependent variable. Association with age was adjusted for gender while association with other risk factors were adjusted for gender, age and, if specified, BMI. A square root transformation was applied to CRP levels to remove positive skewness. A study-wise statistical significance threshold of 3.9×10−7 was used to correct for the number of tests (10 risk factors ×12,808 gene expressions). For each expression trait that was associated with a risk factor and also affected by cis eSNPs, we tested the interaction between the risk factor and the best cis eSNP on expression in a regression model.

Global assessment of associations between the monocyte transcriptome and CVD risk factors

The goal of this analysis was to identify subsets of expression traits independently associated with each risk factor. To increase the robustness of the analysis the population was randomly divided into 2 sub-samples of equal size which were used for screening and validation purpose respectively. The screening step was focused on the subsets of expression traits that were associated with each covariate-adjusted risk factor in univariate analysis at P<3.9×10−6 (Bonferroni correction for 12,808 expressions). Each risk factor and corresponding subset of expression traits were included as dependent and predictor variables respectively in a forward stepwise regression model to identify expression traits that were independently associated with the risk factor (P<0.01). Gene expressions selected at the screening step were then jointly tested in the validation sample for association with the risk factor by multiple regression analysis. This screening/validation procedure was repeated 250 times and for each risk factor, expression traits associated (P<0.01) with the risk factor in more than 25% of the replicates are reported.

Power of the SNP-expression association analysis

Power was calculated using the program Quanto (http://hydra.usc.edu/GxE/). Assuming a quantitative expression trait with mean 0 and SD 1, a sample size of 1,490 subjects, a type I error of 5.78×10−12 and an additive allele effect, the study had a 82% power to detect the effect of a SNP explaining 4% of gene expression.

Functional classification of genes

An ontology analysis was performed using the Panther database (http://www.pantherdb.org/). Lists or sublists of genes involved in associations with eSNPs or risk factors were compared to the background list of the 12,808 genes. The P-value calculated by the binomial statistic and Bonferroni-corrected was used.

Quality checking and exclusion of outliers

Population stratification and quality of genotypes and expression data were tested extensively and outliers were excluded on the basis of multidimensional scaling analysis (see Methods S2)

GHS_Express

A downloadable SQL database compiling the results of the various associations tested is available online (http://genecanvas.ecgene.net/uploads/ForReview/), see also Methods S1. This database can be used to test specific hypotheses.

Supporting Information

Characterization of polymorphic probes in eQTLs.

(0.33 MB DOC)

Loci identified in GWAS of BMI and BP - associations of lead/tag SNPs with phenotypes and expressions, and of expressions with phenotype in GHS.

(0.07 MB DOC)

Sets of gene expressions robustly and independently associated with each risk factor in the validation samples.

(0.21 MB DOC)

GHS-Express database.

(0.18 MB DOC)

Data quality checking.

(0.21 MB DOC)

GHS - Characteristics of cis eQTLs.

(0.40 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Stranger et al.

(0.10 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Dixon et al.

(0.14 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Schadt et al.

(0.28 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Goring et al.

(0.83 MB XLS)

GHS - Expression traits associated with risk factors.

(0.29 MB XLS)

GHS - Interaction cis eSNPs with risk factors.

(0.12 MB XLS)

Acknowledgments

We thank John Todd and Chris Wallace for very helpful comments on our manuscript.

We acknowledge Carolin Neukirch, Fatma Karaman, Jutta Bähr and Stefanie Müller for technical assistance, Andreas Weith for help during technical performance of GWV and GWE experiments and Alexandru Munteanu for assistance in informatics.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: In this study, Boehringer Ingelheim provided payment for two employees for expression microarray analyses and array purchase and PHILIPS Medical Systems provided instruments for ultrasound studies. However, this does not alter the authors' adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials, as detailed online in the guide for authors of the Journal.

Funding: The Gutenberg Heart Study is funded through the government of Rheinland-Pfalz (Stiftung Rheinland Pfalz für Innovation, contract number AZ 961-386261/733), the research programs Wissen schafft Zukunft and Schwerpunkt Vaskuläre Prävention of the Johannes Gutenberg-University of Mainz and its contract with Boehringer Ingelheim and PHILIPS Medical Systems including an unrestricted grant for the Gutenberg Heart Study. Specifically, the research reported in this article was supported by the National Genome Network NGFNplus (contract number project A3 01GS0833) by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany. For this particular research paper, Boehringer Ingelheim provided payment of two employees for expression microarray analyses and array purchase. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Stranger BE, Nica AC, Forrest MS, Dimas A, Bird CP, et al. Population genomics of human gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1217–24. doi: 10.1038/ng2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon AL, Liang L, Moffatt MF, Chen W, Heath S, et al. A genome-wide association study of global gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1202–7. doi: 10.1038/ng2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Yang X, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Göring HHH, Curran JE, Johnson MP, Dyer TD, Charlesworth J, et al. Discovery of expression QTLs using large-scale transcriptional profiling in human lymphocytes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1208–16. doi: 10.1038/ng2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emilsson V, Thorleifsson G, Zhang B, Leonardson AS, Zink F, et al. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature. 2008;452:423–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idaghdour Y, Czika W, Shianna KV, Lee SH, Visscher PM, et al. Geographical genomics of human leukocyte gene expression variation in southern Morocco. Nat Genet. 2010;42:62–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cookson W, Liang L, Abecasis G, Moffatt M, Lathrop M. Mapping complex disease traits with global gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:184–94. doi: 10.1038/nrg2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nica AC, Dermitzakis ET. Using gene expression to investigate the genetic basis of complex disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R129–134. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung VG, Spielman RS. Genetics of human gene expression: mapping DNA variants that influence gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:595–604. doi: 10.1038/nrg2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilad Y, Rifkin SA, Pritchard JK. Revealing the architecture of gene regulation: the promise of eQTL studies. Trends Genet. 2008;24:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crujeiras AB, Parra D, Milagro FI, Goyenechea E, Larrarte E, et al. Differential expression of oxidative stress and inflammation related genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in response to a low-calorie diet: a nutrigenomics study. OMICS. 2008;12:251–261. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Büttner P, Mosig S, Funke H. Gene expression profiles of T lymphocytes are sensitive to the influence of heavy smoking: A pilot study. Immunogenetics. 2007;59:37–43. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capel F, Klimcáková E, Viguerie N, Roussel B, Vítková M, et al. Macrophages and adipocytes in human obesity: adipose tissue gene expression and insulin sensitivity during calorie restriction and weight stabilization. Diabetes. 2009;58:1558–1567. doi: 10.2337/db09-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Magalhães JP, Curado J, Church GM. Meta-analysis of age-related gene expression profiles identifies common signatures of aging. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:875–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan Q, Zhao J, Li S, Christiansen L, Kruse TA, et al. Differential and correlation analyses of microarray gene expression data in the CEPH Utah families. Genomics. 2008;92:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, Schadt EE, Wang S, Wang H, Arnold AP, et al. Tissue-specific expression and regulation of sexually dimorphic genes in mice. Genome Res. 2006;16:995–1004. doi: 10.1101/gr.5217506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellegren H, Parsch J. The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:689–698. doi: 10.1038/nrg2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber C, Zernecke A, Libby P. The multifaceted contributions of leukocyte subsets to atherosclerosis: lessons from mouse models. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:802–15. doi: 10.1038/nri2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Garnier S, Grundberg E, Kwan T, et al. A risk haplotype of STAT4 for systemic lupus erythematosus is over-expressed, correlates with anti-dsDNA and shows additive effects with two risk alleles of IRF5. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2868–2876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Handunnetthi L, Ramagopalan SV, Ebers GC, Knight JC. Regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II gene expression, genetic variation and disease. Genes Immun. 2010;11:99–112. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aulchenko YS, Ripatti S, Lindqvist I, Boomsma D, Heid IM, et al. Loci influencing lipid levels and coronary heart disease risk in 16 European population cohorts. Nat Genet. 2009;41:47–55. doi: 10.1038/ng.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton-Cheh C, Johnson T, Gateva V, Tobin MD, Bochud M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight loci associated with blood pressure. Nat Genet. 2009;41:666–76. doi: 10.1038/ng.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kathiresan S, Willer CJ, Peloso GM, Demissie S, Musunuru K, et al. Common variants at 30 loci contribute to polygenic dyslipidemia. Nat Genet. 2009;41:56–65. doi: 10.1038/ng.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linsel-Nitschke P, Heeren J, Aherrahrou Z, Bruse P, Gieger C, et al. Genetic variation at chromosome 1p13.3 affects sortilin mRNA expression, cellular LDL-uptake and serum LDL levels which translates to the risk of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;208:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samani NJ, Braund PS, Erdmann J, Götz A, Tomaszewski M, et al. The novel genetic variant predisposing to coronary artery disease in the region of the PSRC1 and CELSR2 genes on chromosome 1 associates with serum cholesterol. J Mol Med. 2008;86:1233–1241. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trégouët D, König IR, Erdmann J, Munteanu A, Braund PS, et al. Genome-wide haplotype association study identifies the SLC22A3-LPAL2-LPA gene cluster as a risk locus for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:283–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erdmann J, Grosshennig A, Braund PS, König IR, Hengstenberg C, et al. New susceptibility locus for coronary artery disease on chromosome 3q22.3. Nat Genet. 2009;41:280–282. doi: 10.1038/ng.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, Musunuru K, Ardissino D, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet. 2009;41:334–341. doi: 10.1038/ng.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Visel A, Zhu Y, May D, Afzal V, Gong E, et al. Targeted deletion of the 9p21 non-coding coronary artery disease risk interval in mice. Nature. 2010;464:409–12. doi: 10.1038/nature08801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarinova O, Stewart AFR, Roberts R, Wells G, Lau P, et al. Functional analysis of the chromosome 9p21.3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1671–1677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auffray C, Fogg DK, Narni-Mancinelli E, Senechal B, Trouillet C, et al. CX3CR1+ CD115+ CD135+ common macrophage/DC precursors and the role of CX3CR1 in their response to inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:595–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou T, Chen Y, Hao L, Zhang Y. DC-SIGN and immunoregulation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2006;3:279–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collot-Teixeira S, Martin J, McDermott-Roe C, Poston R, McGregor JL. CD36 and macrophages in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:468–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zudaire E, Portal-Núñez S, Cuttitta F. The central role of adrenomedullin in host defense. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:237–44. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0206123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan Y, Chiang M, Tsai Y, Su S, Chen M, et al. Absence of the Transcriptional Repressor Blimp-1 in Hematopoietic Lineages Reveals Its Role in Dendritic Cell Homeostatic Development and Function. J Immunol. 2009;183:7039–7046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He JQ, Wiesmann C, van Lookeren Campagne M. A role of macrophage complement receptor CRIg in immune clearance and inflammation. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:4041–4047. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood Monocytes: Development, Heterogeneity, and Relationship with Dendritic Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:669–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Heterogeneous In Vivo Behavior of Monocyte Subsets in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1424–32. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Combadière C, Potteaux S, Gao J, Esposito B, Casanova S, et al. Decreased atherosclerotic lesion formation in CX3CR1/apolipoprotein E double knockout mice. Circulation. 2003;107:1009–16. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057548.68243.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oram JF, Vaughan AM. ATP-Binding cassette cholesterol transporters and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:1031–43. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250171.54048.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitz G, Langmann T, Heimerl S. Role of ABCG1 and other ABCG family members in lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1513–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zelcer N, Hong C, Boyadjian R, Tontonoz P. LXR regulates cholesterol uptake through Idol-dependent ubiquitination of the LDL receptor. Science. 2009;325:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1168974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindholm D, Bornhauser BC, Korhonen L. Mylip makes an Idol turn into regulation of LDL receptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3399–3402. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flowers MT, Ntambi JM. Role of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase in regulating lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:248–256. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282f9b54d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe M, Layne MD, Hsieh C, Maemura K, Gray S, et al. Regulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation by AT-rich interaction domain transcription factors Mrf2alpha and Mrf2beta. Circ Res. 2002;91:382–389. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000033593.05545.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasky-Su J, Neale BM, Franke B, Anney RJL, Zhou K, et al. Genome-wide association scan of quantitative traits for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identifies novel associations and confirms candidate gene associations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1345–1354. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rimkus C, Martini M, Friederichs J, Rosenberg R, Doll D, et al. Prognostic significance of downregulated expression of the candidate tumour suppressor gene SASH1 in colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1419–1423. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cox MA, Gomes B, Palmer K, Du K, Wiekowski M, et al. The pyrimidinergic P2Y6 receptor mediates a novel release of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in monocytic cells stimulated with UDP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Charles PC, Alder BD, Hilliard EG, Schisler JC, Lineberger RE, et al. Tobacco use induces anti-apoptotic, proliferative patterns of gene expression in circulating leukocytes of Caucasian males. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:38. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-1-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–1737. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimas AS, Deutsch S, Stranger BE, Montgomery SB, Borel C, et al. Common regulatory variation impacts gene expression in a cell type-dependent manner. Science. 2009;325:1246–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1174148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huber W, von Heydebreck A, Sültmann H, Poustka A, Vingron M. Variance stabilization applied to microarray data calibration and to the quantification of differential expression. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(Suppl 1):S96–104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.suppl_1.s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Development Core Team. 2008. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing Available at: http://www.R-project.org.

- 57.Fisher R. London: Oliver and Boyd; 1932. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characterization of polymorphic probes in eQTLs.

(0.33 MB DOC)

Loci identified in GWAS of BMI and BP - associations of lead/tag SNPs with phenotypes and expressions, and of expressions with phenotype in GHS.

(0.07 MB DOC)

Sets of gene expressions robustly and independently associated with each risk factor in the validation samples.

(0.21 MB DOC)

GHS-Express database.

(0.18 MB DOC)

Data quality checking.

(0.21 MB DOC)

GHS - Characteristics of cis eQTLs.

(0.40 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Stranger et al.

(0.10 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Dixon et al.

(0.14 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Schadt et al.

(0.28 MB XLS)

Comparison cis eQTL in GHS and the study of Goring et al.

(0.83 MB XLS)

GHS - Expression traits associated with risk factors.

(0.29 MB XLS)

GHS - Interaction cis eSNPs with risk factors.

(0.12 MB XLS)