Abstract

Rationale

The kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonist, JDTic, was reported to prevent stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-maintained responding and to have antidepressant-like effects.

Objectives

Our objectives were to determine whether analogs of JDTic retained KOR antagonist activity and whether an orally effective analog prevented footshock-induced cocaine reinstatement.

Methods

RTI-194 (i.g. 1–30 mg/kg, s.c. 0.3–10 mg/kg, and i.p. 30 mg/kg), RTI-212 (s.c. 0.3–10 mg/kg and i.p. 30 mg/kg), and RTI-230 (i.g. 3–30 mg/kg and i.p. 1–30 mg/kg) were evaluated for their ability to block diuresis induced by 10-mg/kg U50,488 in rats. RTI-194 was additionally evaluated i.g. (3–100 mg/kg) for its ability to prevent footshock-induced reinstatement of responding previously reinforced with 0.5-mg/kg/inf cocaine.

Results

RTI-194 significantly (p<0.05) attenuated U50,488-induced diuresis when given i.g., s.c., and i.p. RTI-194s effectiveness increased 1 week following administration. RTI-212 was ineffective. RTI-230 was ineffective when given i.g., but blocked diuresis at 24 h and 8 days (1, 10, and 30 mg/kg), 15 days (10 and 30 mg/kg), 22 and 29 days (30 mg/kg) following i.p. administration. Footshock reinstated responding in vehicle—but not RTI-194 (30 and 100 mg/kg)-treated rats.

Conclusions

RTI-194 and RTI-230 are effective KOR antagonists, and RTI-194 is now included with JDTic as the only reported compounds capable of antagonizing the KOR following oral administration. The failure of stress to reinstate cocaine seeking in rats treated with RTI-194 is consistent with results reported with JDTic, although it had less efficacy in lowering response levels than JDTic, suggesting a diminished overall effectiveness relative to it.

Keywords: Cocaine, Self-administration, Rats, Kappa, Opioid, JDTic, Reinstatement, Diuresis, Stress, Nor-binaltorphimine

Introduction

In recent years, the kappa opioid receptor (KOR) system has become increasingly implicated as a modulator of stress-related and addictive behaviors (for recent review, see Bruchas et al. 2009). For example, McLaughlin et al. have reported that the KOR antagonist, nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI), blocks stress-induced potentiation of cocaine-conditioned place preference (CPP) and analgesia and reduces stress-induced immobility produced following the forced-swim test in mice (McLaughlin et al. 2003, 2006). Others have reported that the KOR antagonists can attenuate (Land et al. 2008; Menendez et al. 1993; Takahashi et al. 1990), and KOR agonists augment, the behavioral effects to stress (Katoh et al. 1990).

Exaggerated responsivity to stress is often present in former opiate and cocaine abusers, and this has been linked to chronic relapse (Kreek 1987). Preclinically, KOR agonists have been reported to exacerbate, and KOR antagonists attenuate, stress-related precipitations of drug-seeking like behavior. For example, the KOR agonists, spiradoline and enadoline, induce reinstatement of lever pressing previously reinforced with cocaine in squirrel monkeys (Valdez et al. 2007); and the KOR agonist, U50,488, induces reinstatement of cocaine CPP in mice (Redila and Chavkin 2008). Additionally, several studies now have documented that KOR antagonists blunt stress-induced cocaine relapse-like behavior in laboratory animals. For example, the KOR antagonist JDTic ((3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-{(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl]methyl}-2-methylpropyl}-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide) blocks footshock-induced reinstatement of lever pressing previously reinforced with cocaine in rats (Beardsley et al. 2005), and nor-BNI blocks stress-induced potentiation of cocaine CPP in mice (McLaughlin et al. 2006), and nor-BNI (Redila and Chavkin 2008) and the KOR peptide antagonists zyklophin ([N-BenzylTyr1,cyclo(D-Asp5,Dap8)]Dyn A-(1–11) amide) (Aldrich et al. 2009) and arodyn ([AcPhe1,2,3, Arg4,D-Ala8]dynorphin A-(1–11) amide) (Carey et al. 2007) block stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine CPP in mice.

JDTic has other interesting properties, including high selectivity for the KOR relative to other opiate receptors, antidepressant-like effects, oral bioavailability, and an extremely long duration of action lasting several weeks (Beardsley et al. 2005; Carroll et al. 2004; Thomas et al. 2001, 2003, 2004), all of which could be favorable features of a pharmacotherapeutic. JDTic is in development as a pharmacotherapeutic for treating stress-initiated relapse in cocaine-dependent users, and an Investigational New Drug (IND) application is in preparation for its clinical evaluation. Very few compounds have been found to have KOR antagonistic effects in vivo when administered systemically, and evaluating analogs of JDTic could help identify compounds to add to this select number and could illuminate structural requirements to serve as selective KOR antagonists. An objective of the present study was to determine whether analogs of JDTic that had demonstrated potent and selective KOR antagonistic effects in vitro (Cai et al. 2008) also showed in vivo KOR antagonist properties like JDTic. For this aim, three analogs of JDTic, RTI-194 ((3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-[(1S,2S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl] methyl}-2-methylbutyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide dihydrochloride), RTI-212 ((3R)-N-[(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl] methyl}-2-methylpropyl]-7-methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroiso-quinoline-3-carboxamide dihydrochloride), and RTI-230 ((3R)-N-[(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-carbamoylphenyl)-3,4-dime-thylpiperidin-1-yl]methyl}-2-methylpropyl]-7-hydroxy-1, 2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (2) dihydrochloride) were evaluated for their ability to block diuresis induced by the KOR agonist U50,488 in rats as a demonstration of in vivo KOR antagonism. Because KOR agonist-induced diuresis is mediated by the central nervous system (Brooks et al. 1993; Cabral et al. 1997; Ko et al. 2003), we hypothesized that antagonists of this effect would likely also be effective as antagonists of KOR-mediated stress effects. Because we found that RTI-194 was able to block U50,488-induced diuresis and with a better overall profile than the other compounds tested, it was additionally evaluated for its ability to prevent footshock-induced reinstatement in rats that had been previously reinforced with cocaine.

Material and methods

Subjects

Adult male experimentally naïve Long–Evans hooded rats (Harlan Sprague–Dawley, USA) were used. They were housed one per cage (VCU) or four per cage (RTI) in a temperature-controlled (22°C) facility on a regular 12/12 light/dark cycle. They were allowed ad libitum water and rat chow and habituated to the vivarium for at least 1 week prior to commencement of testing. All animals received care according to Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, DHHS Publication, Revised, 1996. The animal care facilities were certified by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee either at the Virginia Commonwealth University or the Research Triangle Institute.

Evaluating KOR antagonism by blocking the diuretic effect of U50,488

Procedure

The effectiveness of test compounds to block U50,488-induced diuresis was evaluated using methods adapted from Leander (1983) that were similar to those used during a previous evaluation of JDTic for its ability to block U50,488-induced diuresis (Beardsley et al. 2005; Carroll et al. 2004).

Tests with RTI-194 and RTI-212 (conducted at RTI International)

On test days, rats were brought to the metabolism suite approximately 1 h before injections and immediately returned to the vivarium following testing. There were two test days separated by 7 days. On each test day, a rat received two consecutive injections and immediately placed into a standard metabolism cage. The first injection was either the vehicle appropriate for the tested route of administration or a dose of the test compound, and the second injection was either 10-mg/kg s.c. U50,488 or its vehicle. If a rat was scheduled to receive a dose of a test compound, it was only administered drug on the first test day; 7 days later on the second test day, it received the drug’s vehicle instead. During test sessions, the weight in grams of urine output was measured hourly for 5 h and converted to mls. Only the cumulative 5-h totals of urine volume were used in the analyses. The drugs were tested following their s.c. (0.3–10 mg/kg) administration. Additionally, because of RTI-194s effectiveness when administered s.c., it was also tested following its i.g. (1–30 mg/kg) administration. Because it was surprising to us that RTI-212 was ineffective following s.c. testing, it was additionally tested i.p. at dose (30 mg/kg) sufficiently large to preclude further interest as a drug developmental candidate if also found ineffective. RTI-194 and JDTic were also tested i.p at 30 mg/kg as positive controls to RTI-212. Rats tested with U50,488s vehicle+water were not concurrently tested with the rats tested with RTI-194 and RTI-212; however, groups of rats tested with U50,488s vehicle+water are routinely tested in this laboratory and results with three such treated groups are provided in the text.

Tests with RTI-230 (conducted at VCU)

Tests were conducted similarly as those with the other antagonists except that for the first test, each rat was administered either vehicle or the test compound and 24 h later was administered 10-mg/kg U50,488 s.c., and then were individually placed in standard metabolism cages in which urine was collected and measured by volume after 5 h (consistent with the way JDTic had been previously tested and reported by this laboratory) (Beardsley et al. 2005). Tests were conducted at 1, 10 and 30 mg/kg i.p. of RTI-230 (N=8 per group) and at 3, 10 and 30 mg/kg i.g. (N=4 per group). JDTic (30 mg/kg i.g., N=8) was also tested as a positive control during i.g. studies. The rats were subsequently tested at 8 and 15 days post-administration during i.p. studies and at 10 days post-administration during i.g. studies. Subsets (N=4) of the water-vehicle and the 30-mg/kg RTI-230 groups tested i.p. were additionally tested 22 days and 29 days following their administration.

Reinstatement testing procedures

Subjects

Rats used in reinstatement studies were approximately 9 weeks old at the start of studies and were similarly handled as those described for diuresis studies (VCU), except that they were allowed ad libitum water and rat chow for at least 1 week prior to commencement of training and then were food restricted to maintain their body weight at approximately 320 g. After acclimation to the vivarium, indwelling venous catheters were implanted into the right external jugular vein using procedures and catheters similar to that described previously (Shelton and Beardsley 2005; Shelton et al. 2004). Rats were allowed to recover from surgery for at least 5 days before self-administration training began. Between sessions, the catheters were flushed and filled with 0.1 ml of a 25% glycerol/75% sterile saline locking solution containing 250 units/ml heparin, 250 mg/ml ticarcillin, and 9 mg/ml clavulanic acid. Periodically throughout training, metho-hexital (1.5 mg/kg) or ketamine (5 mg/kg) was infused through the catheters to determine patency as inferred when immediate anesthesia was induced. If a catheter was determined to have lost patency, the left external jugular was catheterized and the rat was returned to testing.

Apparatus

Commercially obtained test chambers equipped with two retractable levers, a 5-W house light and a Sonalert® tone generator (MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA) emitting a 2,900 Hz 60-dB tone, were used. Positioned above each lever was a white cue light. The grid floors of the chambers were connected to a shock generating device which could deliver 0.87 mA scrambled footshock. Infusions were delivered in a 0.18-ml volume by a 6-s activation of infusion pumps (Model PHS-100; MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA). Recordings of lever presses and activations of lights, shockers, pumps, and Sonalerts were accomplished by a microcomputer, interface, and associated software (MED-PC® IV, MED Associates, Inc., St. Albans, VT, USA).

Self-administration training and extinction

Cocaine self-administration training sessions were conducted 5 days per week (M–F) for 2 h daily. Initially, each response (fixed ratio 1 (FR1)) on the right-side lever resulted in the delivery of 0.5-mg/kg cocaine infusion (0.18 ml/6 s). For the duration of the infusion, the tone sounded and the stimulus lights above both levers flashed at 3 Hz. Active (right side) lever presses during the infusions as well as all inactive (left side) lever presses were recorded but were without scheduled consequences. Rats were eligible for extinction and reinstatement testing after they had received a minimum of 17 cocaine training sessions, with 15 or more cocaine infusions per session for four consecutive sessions. Extinction sessions were identical to cocaine self-administration sessions except that responding did not result in cocaine infusions. Two-hour extinction sessions were conducted once daily, 7 days per week, for 12 days. Unlike during self-administration training, extinction sessions were conducted 7 days per week to prevent variations in the durations of drug abstinence prior to testing. To acclimate the rats to compound administration, all were gavaged with vehicle 30 min after the end of the session on days 9–11 of extinction. After the last day of extinction, they were considered eligible for testing if the mean number of active-lever presses on the last 3 days of extinction was lower than the mean number of active-lever presses on the first 3 days of extinction, and the number of active-lever presses was ≤62 during the final extinction session (≤62 presses was chosen based upon “62” being 2 SD from the mean number of presses from an earlier, untreated pilot group of 36 cocaine-trained rats). Rats that did not meet this extinction criterion were omitted from the study (11 rats were excluded for failing to meet these extinction criteria).

Footshock-induced reinstatement testing

Twelve different rats were tested in each of six reinstatement conditions in which they were gavaged with either sterile water (vehicle used for all doses except 100 mg/kg of RTI-194), 2% methylcellulose in water (vehicle used only for 100 mg/kg of RTI-194), or 3-, 10-, 30- or 100-mg/kg RTI-194, 30 min after the last extinction session. Sterile water and doses lower than 100-mg/kg RTI-194 were tested first. Subsequently, methylcellulose-vehicle and 100-mg/kg RTI-194 were tested. Assignment of a rat to a particular group was made immediately after the last extinction session and was made to maximize the similarity of the number of rats tested in each group and their lever pressing levels emitted on the last day of extinction at that point in time. On the following day, the “testday”, all rats were given 15 min of intermittent shock and then tested during a 2-h reinstatement session. Shock was administered intermittently at 0.87 mA, with a 0.5-s activation time and an average inter-activation interval of 40 s, during the 15 min immediately prior to the start of a test session.

Drugs

JDTic ((3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-((1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl]methyl}-2-methyl-propyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide (Thomas et al. 2003), RTI-194 ((3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-[(1S,2S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl] methyl}-2-methylbutyl]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide dihydrochloride), RTI-212 ((3R)-N-[(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl] methyl}-2-methylpropyl]-7-methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroiso-quinoline-3-carboxamide dihydrochloride), and RTI-230 ((3R)-N-[(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-Carbamoylphenyl)-3, 4-dimethylpiperidin-1-yl]methyl}-2-methylpropyl]-7-hydroxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxamide (2) dihydrochloride) were synthesized as previously reported (Cai et al. 2008). Cocaine HCl (National Institute on Drug Abuse, USA) was diluted in heparinized (5 units/ml) sterile 0.9% saline for i.v. self-administration. U50,488 was dissolved in sterile 0.9% saline and administered s.c. All other drugs were dissolved or suspended in sterile water, except when RTI-194 was administered in a dose of 100 mg/kg i.g., in which case it was suspended in 2% methylcellulose in sterile water because of its inability to be satisfactorily suspended in plain water (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, #M0430, USA). All test compounds administered i.g., i.p. or s.c. were given in a volume equivalent to 1 ml/kg.

Data analysis

Analysis of U50,488 results

To determine the efficacy of each drug to antagonize the diuretic effects of U50,488, the volumes of urine collected (ml) after 5 h were analyzed by drug (including vehicle) and route of administration using a mixed-model ANOVA (“dose” and repeated measures on “time”) with groups compared within time of testing using Bonferroni post hoc tests. Because not all rats were tested at all time points during i.p. administration of RTI-230, a repeated measures ANOVA was precluded. Instead, data were analyzed at 1, 8 and 15 days post-administration using a one-way ANOVA within each time point with test groups compared to vehicle using Dunnett’s post tests. Because only water-vehicle and 30-mg/kg i.p. RTI-230 were tested 22 and 29 days post-RTI-230 administration, unpaired t tests were conducted comparing the effects of RTI-230 with those of water at those time points. AD50 values (±95% CI) for reducing by 50% the levels of the volume of urine excreted by the vehicle-treated group challenged with U50,488 were determined using curvilinear fit procedures assuming a standard Hill slope.

Analysis of cocaine reinstatement results

Initially, reinstatement testday data were analyzed using the Grubbs test for outliers (Extreme Studentized Deviate), and a rat’s data were excluded from all analyses if p<0.05 (GraphPad QuickCalcs Web site: http://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/Grubbs1.cfm, accessed October 2009). Of the 72 rats evaluated, one rat in the methylcellulose-vehicle group had its data excluded for failing to meet the Grubbs test. Subsequently, water-vehicle and RTI-test groups of 3, 10 and 30 mg/kg were analyzed separately from the methylcellulose-vehicle treated and 100-mg/kg RTI-194 groups. Numbers of active-lever presses (i.e., the right-side lever, the presses of which were previously reinforced with cocaine) during the last day of self-administration, the last day of extinction, and during the test day were subjected to a mixed-model ANOVA (repeated measures on “phase of testing”) with groups compared within phase of testing using Bonferroni post hoc tests regardless of each ANOVA’s overall significance. To evaluate whether foot-shock effectively reinstated responding, paired t tests were conducted on active-lever presses comparing results occurring on the last day of extinction with those during the reinstatement test session separately for the water-treated and methylcellulose-treated groups, and for any test group for which responding was reduced to below vehicle levels during the reinstatement test (this only occurred at RTI-194 30 and 100 mg/kg, the two highest doses tested) to determine if footshock effectively reinstated responding in these groups. All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism Software (v. 5.0c for Macintosh, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

Results

Effects on U50,488-induced diuresis

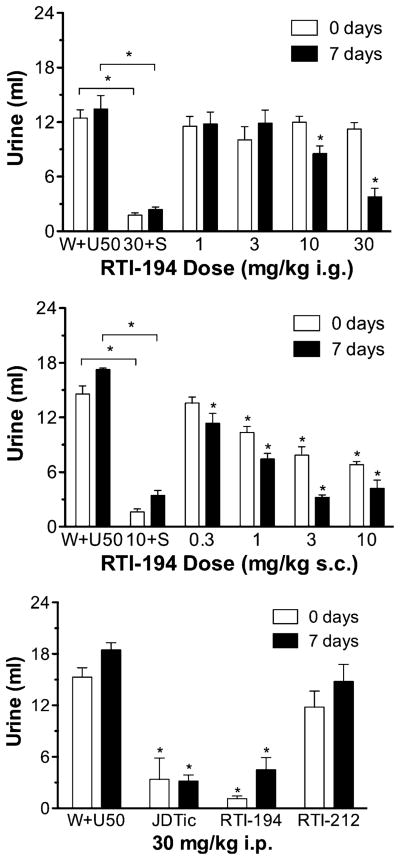

RTI-194 administered i.g. had a significant main effect of dose ([F(5, 18)=18.01, p<0.0001] and time ([F(1, 18)=10.99, p=0.0039] and a dose×time interaction ([F (5, 18)=16.33, p<0.0001] (Fig. 1, upper panel). No dose significantly reduced U50,488-induced diuresis when tested immediately, but 10 mg/kg (t=3.376, p<0.01) and 30 mg/kg (t=3.803, p<0.001) did so 1 week after administration. The AD50 (CI) for inhibiting U50,488-induced diuresis at 1 week was 34.43 (2.29–518.1) mg/kg. Although rats tested with U50,488s vehicle s.c.+ water s.c. were not concurrently tested with the rats tested with RTI-194 and RTI-212 (see Methods), such treatments are routinely and periodically evaluated in the laboratory. The mean (±SEM) values (ml) for three such groups (N=4/group) tested with U50,488s vehicle s.c.+ water s.c. and composed of experimentally naive rats tested after tests with RTI-194 and RTI-212 had been completed were 2.1 (±1.0), 2.3 (±2.3), and 1.7 (±0.6) ml when tested immediately following initial water injection and were 1.0 (±0.6), 2.5 (±0.2), and 1.0 (±0.6) ml when tested 1 week following initial water injection.

Fig. 1.

Upper panel: Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session when RTI-194 was given i.g. “W+U50” = water vehicle co-administered with 10-mg/kg U50,488; “30+S” = 30-mg/kg RTI-194 co-administered with saline. Vertical brackets indicate SEM. Asterisks above horizontal brackets indicate that the connected conditions were significantly (p<0.05) different from one another. Asterisks without associated horizontal brackets indicate significantly (p<0.05) different relative to corresponding vehicle levels. N=4 for all conditions. Middle panel: Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session when RTI-194 was given s.c. “10+S”=10-mg/kg RTI-194 co-administered with saline. Other details as described for the upper panel. Lower panel: Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session during i.p. tests with 30-mg/kg JDTic, 30-mg/kg RTI-194, and 30-mg/kg RTI-212. Other details as described for the upper panel

RTI-194 s.c. had a significant main effect of dose ([F(5, 18)=82.77, p<0.0001] and time ([F(1, 18)=16.54, p= 0.0007] and a dose×time interaction ([F(5, 18)=13.60, p< 0.0001] (Fig. 1, middle panel). In contrast to the i.g. results, RTI-194 given s.c. and tested immediately significantly reduced U50,488-induced diuresis at all doses but 0.3 mg/kg, the lowest dose tested. All doses significantly reduced U50,488-induced diuresis 1 week following RTI-194s administration. The AD50s for reducing U50,488-induced diuresis when RTI-194 was tested immediately and 1 week following its administration were 1.069 (0.42–2.69) mg/kg and 0.35 (0.20–0.64) mg/kg, respectively. At 30 mg/kg i.p. (Fig. 1, bottom panel), it also blocked U50,488-induced diuresis immediately (t=6.66, p<0.001) and 1 week later (t=6.57, p<0.001).

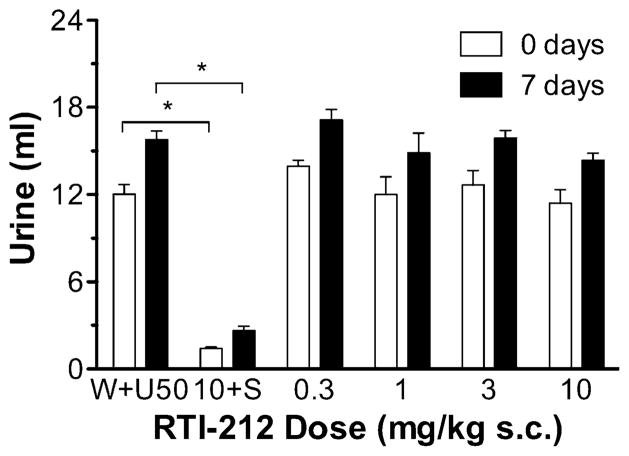

RTI-212 s.c. had a significant main effect of dose ([F (5, 18)=60.42, p<0.0001] and time ([F(1, 18)=58.94, p< 0.0001] but not a dose×time interaction (Fig. 2). However, no dose significantly reduced U50,488-induced diuresis immediately or 1 week later. As a probe, RTI-212 was also tested at 30 mg/kg i.p. (Fig. 1, bottom panel), but it neither had a significant effect immediately nor 1 week later. As a positive control, JDTic was also tested at 30 mg/kg i.p. (Fig. 1, bottom panel); it significantly reduced U50,488-induced diuresis immediately (t=5.595, p<0.001) and 1 week later (t=7.193, p<0.001).

Fig. 2.

Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session when RTI-212 was given s.c. “10+S”=10-mg/kg RTI-212 co-administered with saline. Other details as described for Fig. 1, upper panel

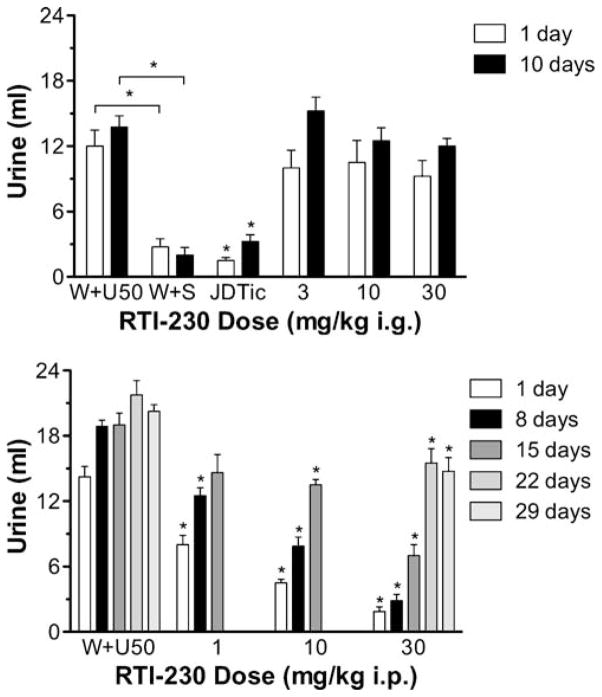

RTI-230 was without effects on U50,488-induced diuresis following i.g. administration (Fig. 3, upper panel). JDTic at 30 mg/kg i.g. as a positive control significantly blocked U50,488-induced diuresis immediately (q=6.737, p<0.001) and 10 days later (q=8.81, p<0.001). In contrast to the i.g. results, all tested doses of RTI-230 administered i.p. (1, 10, and 30 mg/kg) significantly (p<0.05) reduced U50,488-induced diuresis 24 h and 8 days later (Fig. 3, bottom panel). The AD50s (CI) at 24 h and at 8 days i.p. were 0.77 (0.36–1.62) mg/kg and 2.67 (0.94–7.60) mg/kg, respectively. At 15 days, 10 mg/kg (q=2.870, p<0.05) and 30 mg/kg (q=5.423, p<0.001) remained effective. Only 30 mg/kg was tested at 22 and 29 days; although urine output approached that of water+U50,488, it remained significantly reduced at 22 days (t=3.351, p=0.0154) and 29 days (t=3.390, p=0.0077).

Fig. 3.

Upper panel: Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session when RTI-230 or 30-mg/kg JDTic was given i.g. “W+S” = water co-administered with saline; “JDTic”=30-mg/kg JDTic. N=4 except for JDTic in which N=8. Other details as described for Fig. 1. Lower panel: Mean ml of urine accumulated during the 5-h test session when RTI-230 was given i.p. days 1 and 8, N=8; day 15, “W+U50” and 30-mg/kg RTI-230, N=4; 30-mg/kg JDTic, N=6; 1 and 10-mg/kg RTI-230, N=8; days 22 and 29, N=4. Other details as described for Fig. 1, upper panel

Effects of RTI-194 on stress-induced cocaine reinstatement

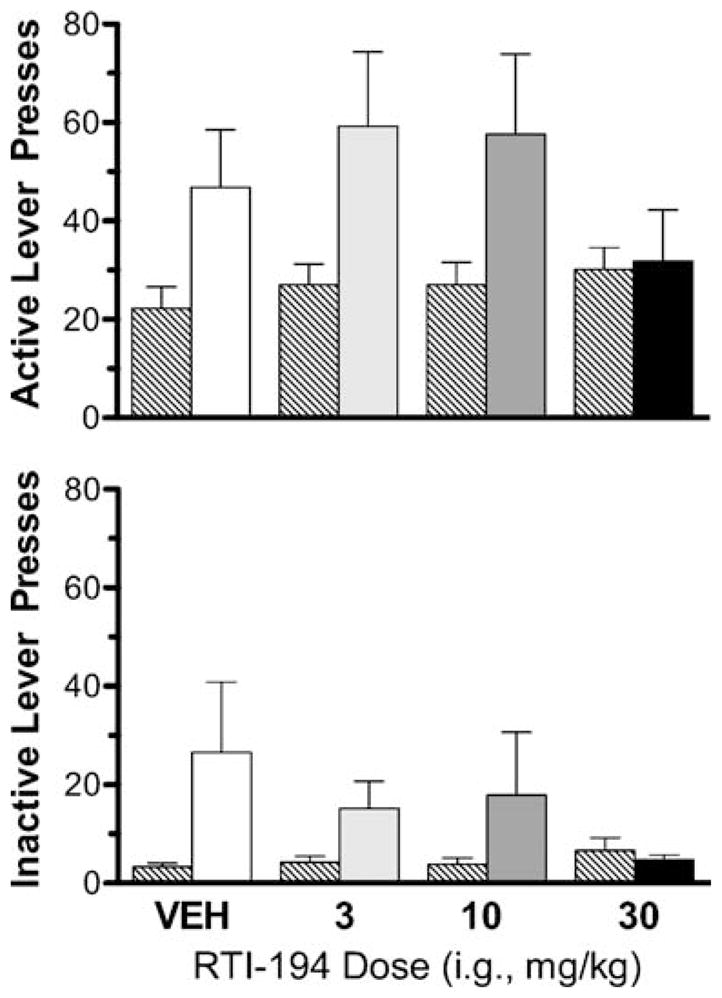

Groups were all trained to similar levels of self-administration and extinguished to similar levels; Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that none of the pairwise comparisons of active-lever presses during the last session of self-administration, or during the last session of extinction, amongst test groups in which water was the vehicle (water, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg), or between test groups in which methylcellulose was the vehicle (methylcellulose and 100 mg/kg) were significantly different (p>0.05). The footshock conditions were effective in reinstating responding in that greater numbers of lever presses that occurred during the reinstatement test condition relative to the last session of extinction for both the water-vehicle (t=2.382, p=0.0363) and methylcellulose-vehicle (t=2.353, p= 0.0404) groups. Figure 4 shows results of RTI-194 when tested from 3 to 30 mg/kg i.g. during the last session of extinction (striped bars) and during the reinstatement test condition (un-striped bars) for the active lever (upper panel) and inactive lever (lower panel). Active-lever responding was slightly higher at 3 and 10 mg/kg relative to water levels and reduced at 30 mg/kg. Administering 30-mg/kg RTI-194 prior to the shock reinstatement test session resulted in a mean (±SEM) of 31.83 (±10.43) responses on the active lever, the lowest level of all test groups observed, and was similar to this group’s level of responding on the last day of extinction (30.17±4.43) and non-significantly different from it. Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that levels of active-lever responding by the water-vehicle and 30-mg/kg groups, however, were not statistically different. Administering 100 mg/kg prior to the shock reinstatement test session resulted in a mean (±SEM) of 38.17 (±9.201) responses on the active lever, which was not significantly different from the number (21.83±4.258) this group emitted during the last session of extinction (because of the different vehicle conditions, the methylcellulose and 100-mg/kg groups are not included in Fig. 4). The reduced responding on the active lever by the 100-mg/kg group was not significantly different from the methylcellulose group.

Fig. 4.

Upper panel: Mean active-lever presses during extinction and footshock reinstatement tests with RTI-194. The left-side bar of each pair of bars indicates results on the final session of extinction. The right-side bar of each pair of bars represents results during the footshock reinstatement test. Vertical brackets indicate SEM. N=12 at all conditions. Lower panel: Mean lever presses on the inactive lever during extinction and footshock reinstatement tests with RTI-194. Other details as described for the upper panel

During the reinstatement test condition, inactive-lever presses were irregularly related to dose of RTI-194 tested (Fig. 4, lower panel). Bonferroni post hoc tests indicated that none of the pairwise comparisons of inactive-lever presses during the last session of self-administration, during the last session of extinction, and during the reinstatement test condition for test groups in which water was the vehicle (water, 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg) or for which methylcellulose was the vehicle (methylcellulose and 100 mg/kg) were significantly different (p>0.05).

Discussion

Two of the tested compounds, RTI-194 and 230, heretofore unexamined in vivo, were found to effectively block U50,488-induced diuresis and serve as KOR antagonists in rats, adding to the short list of systemically effective and selective KOR antagonists that include JDTic (Carroll et al. 2004), nor-BNI (Portoghese et al. 1987; Tortella et al. 1989), GNTI (Jewett et al. 2001; Negus et al. 2002), and zyklophin (Aldrich et al. 2009). Surprisingly, RTI-212, although previously found potent for inhibiting U69,593-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Cai et al. 2008; Cuevo et al. 2010), was ineffective via both the i.p. and s.c. routes. During reinstatement tests, footshock reinstated responding in vehicle-treated groups, but failed to do so in rats treated with RTI-194 30 or 100 mg/kg i.g.

RTI-194 was found to effectively block U50,488-induced diuresis indicative of a KOR antagonist. This result is consistent with its ability to inhibit U69,593-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding (Ke value of 0.03 (±0.02) nM) in which it was more selective for the KOR relative to the MOR and DORs by 100- and 800-fold, respectively (Cai et al. 2008; Cuevo et al. 2010). The potency of RTI-194 for blocking U69,593-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was similar to that of JDTic that has a Ke value of 0.02 (±0.01) nM (Cai et al. 2008). Similarly, when examined under identical routes of administration (s.c.) and across a complete dose–effect curve, these compounds had similar potencies when tested immediately after administration for inhibiting U50,488-induced diuresis with AD50s for RTI-194 of 1.069 (0.42–2.69) mg/kg (the present study) and for JDTic of 2.81 mg/kg (Carroll et al. 2004). Both compounds gained potency when tested 1 week following s.c. administration, with the AD50 of RTI-194 dropping to 0.36 (0.20–0.64) mg/kg (this study) and of JDTic to 0.41 mg/kg (Carroll et al. 2004). The slow onset and long duration of activity of both JDTic and RTI-194 are reminiscent of similar characteristics of nor-BNI (Broadbear et al. 1994; Endoh et al. 1992) and GNTI (Negus et al. 2002) but differ from those reported for the KOR peptide antagonist, zyklophin (Aldrich et al. 2009).

RTI-212 differs from JDTic by having a methyl ether in place of the 7-Hydroxy group on the 7-Hydroxy-D-Tic portion of JDTic. RTI-212 demonstrated highly potent in vitro antagonistic activity against U69,593-stimulated [35S] GTPγS binding with a Ke value of 0.06 (±0.01) nM, and was more selective for the KOR relative to the MOR and DORs by 857- and 1976-fold, respectively (Cai et al. 2008). In this in vitro assay, it was only slightly less potent than JDTic (see above) (Cai et al. 2008), yet RTI-212 was ineffective in vivo in antagonizing U50,488-induced diuresis when tested up to 10 mg/kg s.c. or 30 mg/kg i.p., either when evaluated immediately following its administration or 1 week later. It was not functioning as an opioid agonist because it has no intrinsic efficacy in the [35S]GTPγS assay at all three opioid receptors at 10 μM (Cai et al. 2008; Cuevo et al. 2010), and it did not induce diuresis in the rat indicative of a KOR agonist in the present study. The lack of in vivo efficacy was all the more surprising because its calculated logBB (−0.33) value was not indicative of low blood–brain barrier penetration and represented a favorable 0.22 positive log unit shift relative to JDTic (Cuevo et al. 2010). With these favorable physio-chemical parameters, we had predicted that RTI-212 would have a 66% increased presence in the brain relative to JDTic, but its lack of efficacy in attenuating U50,488-induced diuresis suggests otherwise.

RTI-230, the 3-carboxamidophenyl derivative of JDTic, had previously been reported to have potent in vitro antagonistic activity in the U69,593-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding assay (Ke value of 0.10 (±0.04)), with 21- and 478-fold selectivity for the KOR relative to the MOR and DOR, respectively (Cai et al. 2008). Here, it did not block U50,488-induced diuresis up to 30 mg/kg i.g., but was potently effective i.p. with an AD50 of 0.77 (0.36–1.62) mg/kg. Even when 30-mg/kg RTI-230 was evaluated at 22 days and 29 days following its i.p. administration, U50,488-induced urine levels were still lower than those of vehicle control. Thus, its duration of activity is at least as long as that reported for JDTic when it was given s.c. (Carroll et al. 2004). This extreme duration of activity for antagonizing KOR agonist-induced diuresis is representative of all potent and selective KOR antagonists (Carroll et al. 2004). In addition, nor-BNI, GNTI, and JDTic were reported to have similarly long (~2–3 weeks) durations of activity in antagonizing KOR agonist-induced analgesia in mice (Broadbear et al. 1994; Bruchas et al. 2007; Carroll et al. 2004; Horan et al. 1992), rats (Jones and Holtzman 1992), and rhesus monkeys (Butelman et al. 1993), and rate-decreasing effects on operant performance in pigeons (Jewett and Woods 1995). The mechanism for these extended durations of action is not known. It is unlikely that these KOR antagonists are being sequestered in lipid and are then slowly leaching into the CNS over a period of several weeks because pretreatment with reversible, short-acting non-selective KOR antagonists prior to their administration can permanently block expression of their antagonistic activity (Bruchas et al. 2007). Also, it does not appear that these long-acting KOR antagonists reduce KOR receptor populations or irreversibly bind with the KOR receptor, because nor-BNI does not decrease the total KOR density in mouse brain membranes or alter the affinity of KOR agonists (Bruchas et al. 2007). Bruchas et al. (2007) have hypothesized that the long duration of activity of these antagonists is possibly caused by a functional disruption of KOR signaling, because both nor-BNI and JDTic were observed to stimulate c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation, and pretreatment with the JNK inhibitor, SP600125, blocked nor-BNIs long-acting antagonism. The KOR agonists U50,488 and dynorphin, however, also cause a concentration-dependent increase in phospho-JNK activity (Bruchas et al. 2007). The mechanism mediating the extremely long durations of activity of nor-BNI, GNTI, and JDTic awaits definitive identification.

Footshock stress did not reinstate responding in either the 30- or the 100-mg/kg group, in that levels of responding during the last session of extinction relative to those during the reinstatement test session were non-significantly (p> 0.05) different from one another. Footshock stress, however, was able to reinstate responding in both the water-vehicle and the methylcellulose-vehicle groups. Although neither the 30- nor the 100-mg/kg RTI-194 dosage group reinstated and both vehicle groups did, it should be noted that there were no statistical differences in mean response levels (given the analysis used) between RTI-194-treated groups relative to their respective vehicle conditions. Jointly, these observations suggest an incomplete ability of RTI-194 to normalize responding of rats previously reinforced with cocaine when confronted with a stressor. Given that JDTic was able to both prevent footshock-induced reinstatement and to significantly reduce response levels relative to vehicle levels in an earlier study (Beardsley et al. 2005), the data suggest that RTI-194 is likely less efficacious in this regard than JDTic. The direction of change in responding induced by RTI-194, however, is consistent with that seen with JDTic (Beardsley et al. 2005) and is consistent with that observed with other KOR antagonists that have been reported to block the ability of stressors to induce reinstatement of conditioned place preference (Aldrich et al. 2009; Carey et al. 2007; Land et al. 2009; Redila and Chavkin 2008).

The results of this study now add RTI-194 and RTI-230 to the very short list of compounds that include nor-BNI (Portoghese et al. 1987; Tortella et al. 1989), GNTI (Jewett et al. 2001; Negus et al. 2002), JDTic (Carroll et al. 2004), and zyklophin (Aldrich et al. 2009) which are selective in vitro for the kappa versus the mu or delta opiate receptors, and can antagonize the KOR receptor when given systemically. Of these drugs, JDTic and RTI-194 remain the only KOR antagonists which have been demonstrated to have oral bioavailability in antagonizing KOR agonist effects (this study and Beardsley et al. 2005). The observation that RTI-194 prevented footshock-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats adds to the accumulating number of reports implicating the KOR receptor system’s involvement in stress-promoted drug relapse, and in a broader sense, in stress-related phenomena in general, and strengthens interest in exploiting this system for possible pharmacotherapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, U19 DA021002.

Abbreviations

- JDTic

(3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-{(1S)-1-{[(3R,4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl] methyl}-2-methylpropyl}-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide

- KOR

kappa opioid receptor

- nor-BNI

nor-binaltorphimine

- U50,488

trans-3,4-Dichloro-N-methyl-N-(2-[1-pyrrolidinyl] cyclohexyl)benzeneacetamide

- RTI-194

RTI compound RTI-5989-194

- RTI-212

RTI compound RTI-5989-212

- RTI-230

RTI compound RTI-5989-230

- i.g

intragastric

- i.p

intraperitoneal

- s.c

subcutaneous

Contributor Information

Patrick M. Beardsley, Email: pbeardsl@vcu.edu, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA. VCU Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies, Richmond, VA, USA

Gerald T. Pollard, Howard Associates, LLC, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

James L. Howard, Howard Associates, LLC, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

F. Ivy Carroll, Organic and Medicinal Chemistry, Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA.

References

- Aldrich JV, Patkar KA, McLaughlin JP. Zyklophin, a systemically active selective kappa opioid receptor peptide antagonist with short duration of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(43):18396–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Howard JL, Shelton KL, Carroll FI. Differential effects of the novel kappa opioid receptor antagonist, JDTic, on reinstatement of cocaine-seeking induced by footshock stressors vs cocaine primes and its antidepressant-like effects in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbear JH, Negus SS, Butelman ER, de Costa BR, Woods JH. Differential effects of systemically administered nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) on kappa-opioid agonists in the mouse writhing assay. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;115:311–319. doi: 10.1007/BF02245071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DP, Giardina G, Gellai M, Dondio G, Edwards RM, Petrone G, DePalma PD, Sbacchi M, Jugus M, Misiano P, et al. Opiate receptors within the blood–brain barrier mediate kappa agonist-induced water diuresis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Yang T, Schreiber S, Defino M, Kwan SC, Li S, Chavkin C. Long-acting kappa opioid antagonists disrupt receptor signaling and produce noncompetitive effects by activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29803–29811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705540200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Land BB, Chavkin C. The dynorphin/kappa opioid system as a modulator of stress-induced and pro-addictive behaviors. Brain Res. 2009;1314:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelman ER, Negus SS, Ai Y, de Costa BR, Woods JH. Kappa opioid antagonist effects of systemically administered nor-binaltorphimine in a thermal antinociception assay in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1269–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral AM, Varner KJ, Kapusta DR. Renal excretory responses produced by central administration of opioid agonists in ketamine and xylazine-anesthetized rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:609–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai TB, Zou Z, Thomas JB, Brieaddy L, Navarro HA, Carroll FI. Synthesis and in vitro opioid receptor functional antagonism of analogues of the selective kappa opioid receptor antagonist (3R)-7-hydroxy-N-((1S)-1-{[(3R, 4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3, 4-dimethyl-1-pipe ridinyl]methyl}-2-methylpropyl)-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecarboxami de (JDTic) J Med Chem. 2008;51:1849–1860. doi: 10.1021/jm701344b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey AN, Borozny K, Aldrich JV, McLaughlin JP. Reinstatement of cocaine place-conditioning prevented by the peptide kappa-opioid receptor antagonist arodyn. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;569:84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll I, Thomas JB, Dykstra LA, Granger AL, Allen RM, Howard JL, Pollard GT, Aceto MD, Harris LS. Pharmacological properties of JDTic: a novel kappa-opioid receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;501:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cueva JP, Cai TB, Mascarella SW, Thomas JB, Navarro HA, Carroll FI. Synthesis and in vitro opioid receptor functional antagonism of methyl-substituted analogues of (3R)-7-Hydroxy-N-[(1S)-1-{[(3R, 4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3, 4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl] methyl}-2-methylpropyl]-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydro-3-isoquinolinecar-boxamide (JDTic) Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;52(23):7463–72. doi: 10.1021/jm900756t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh T, Matsuura H, Tanaka C, Nagase H. Nor-binaltorphimine: a potent and selective kappa-opioid receptor antagonist with long-lasting activity in vivo. Arch Int Pharma-codyn Ther. 1992;316:30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan P, Taylor J, Yamamura HI, Porreca F. Extremely long-lasting antagonistic actions of nor-binaltorphimine (nor-BNI) in the mouse tail-flick test. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:1237–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DC, Woods JH. Nor-binaltorphimine: an ultra-long acting kappa-opioid antagonist in pigeons. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:815–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett DC, Grace MK, Jones RM, Billington CJ, Portoghese PS, Levine AS. The kappa-opioid antagonist GNTI reduces U50, 488-, DAMGO-, and deprivation-induced feeding, but not butorphanol- and neuropeptide Y-induced feeding in rats. Brain Res. 2001;909:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02624-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DN, Holtzman SG. Long term kappa-opioid receptor blockade following nor-binaltorphimine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;215:345–348. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh A, Nabeshima T, Kameyama T. Behavioral changes induced by stressful situations: effects of enkephalins, dynorphin, and their interactions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253:600–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko MC, Willmont KJ, Lee H, Flory GS, Woods JH. Ultra-long antagonism of kappa opioid agonist-induced diuresis by intra-cisternal nor-binaltorphimine in monkeys. Brain Res. 2003;982:38–44. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02938-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ. Multiple drug abuse patterns and medical consequences. In: Meltzer HY, editor. Psychopharmacology: the third generation of progress. Raven; New York: 1987. pp. 1597–1604. [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin kappa-opioid system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:407–414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land BB, Bruchas MR, Schattauer S, Giardino WJ, Aita M, Messinger D, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD, Chavkin C. Activation of the kappa opioid receptor in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediates the aversive effects of stress and reinstates drug seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(45):19168–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910705106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leander JD. A kappa opioid effect: increased urination in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;224:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Marton-Popovici M, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor antagonism and prodynorphin gene disruption block stress-induced behavioral responses. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5674–5683. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05674.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin JP, Li S, Valdez J, Chavkin TA, Chavkin C. Social defeat stress-induced behavioral responses are mediated by the endogenous kappa opioid system. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1241–1248. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez L, Andres-Trelles F, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Involvement of spinal kappa opioid receptors in a type of footshock induced analgesia in mice. Brain Res. 1993;611:264–271. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90512-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK, Linsenmayer DC, Jones RM, Portoghese PS. Kappa opioid antagonist effects of the novel kappa antagonist 5′-guanidinonaltrindole (GNTI) in an assay of schedule-controlled behavior in rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:412–419. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portoghese PS, Lipkowski AW, Takemori AE. Binaltorphimine and nor-binaltorphimine, potent and selective kappa-opioid receptor antagonists. Life Sci. 1987;40:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redila VA, Chavkin C. Stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking is mediated by the kappa opioid system. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200:59–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1122-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Beardsley PM. Interaction of extinguished cocaine-conditioned stimuli and footshock on reinstatement. Int J Comp Psychol. 2005;18:154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KL, Hendrick E, Beardsley PM. Interaction of noncontingent cocaine and contingent drug-paired stimuli on cocaine reinstatement. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;497:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Senda T, Tokuyama S, Kaneto H. Further evidence for the implication of a kappa-opioid receptor mechanism in the production of psychological stress-induced analgesia. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1990;53:487–494. doi: 10.1254/jjp.53.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JB, Atkinson RN, Rothman RB, Fix SE, Mascarella SW, Vinson NA, Xu H, Dersch CM, Lu Y, Cantrell BE, Zimmerman DM, Carroll FI. Identification of the first trans-(3R, 4R)-dimethyl-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)piperidine derivative to possess highly potent and selective opioid kappa receptor antagonist activity. J Med Chem. 2001;44:2687–2690. doi: 10.1021/jm015521r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JB, Atkinson RN, Vinson NA, Catanzaro JL, Perretta CL, Fix SE, Mascarella SW, Rothman RB, Xu H, Dersch CM, Cantrell BE, Zimmerman DM, Carroll FI. Identification of (3R)-7-hydroxy-N-((1S)-1-[[(3R, 4R)-4-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3, 4-dimethyl-1-piperidinyl]methyl]-2-methylpropyl)-1, 2, 3, 4-tetrahydro-3-iso-quinolinecarboxamide as a novel potent and selective opioid kappa receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3127–3137. doi: 10.1021/jm030094y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JB, Fix SE, Rothman RB, Mascarella SW, Dersch CM, Cantrell BE, Zimmerman DM, Carroll FI. Importance of phenolic address groups in opioid kappa receptor selective antagonists. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1070–1073. doi: 10.1021/jm030467v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortella FC, Echevarria E, Lipkowski AW, Takemori AE, Portoghese PS, Holaday JW. Selective kappa antagonist properties of nor-binaltorphimine in the rat MES seizure model. Life Sci. 1989;44:661–665. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez GR, Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Ruedi-Bettschen D, Spealman RD. Kappa agonist-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in squirrel monkeys: a role for opioid and stress-related mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;323:525–533. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.125484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]