Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the contribution of novelty and simplicity to compliance with a low energy diet among obese outpatients.

Design

Three arm randomised trial for 16 weeks.

Setting

NHS hospital obesity clinic.

Subjects

45 patients aged over 17 years with a body mass index >27 who were not diabetic, pregnant, or lactating.

Interventions

Conventional 3.4 MJ diet (control), isoenergetic novel diet of milk only, or milk plus one designated food daily. Follow up visit every 4 weeks.

Main outcome measure

Weight loss.

Results

Mean weight loss (kg) after 16 weeks on control, milk only, and milk plus diets was 1.7 (95% confidence interval −0.3 to 3.7), 9.4 (5.9 to 12.9), and 7.0 (2.7 to 11.3) respectively. Weight loss on the novel diets was significantly greater than on the control diet.

Conclusions

Dietary treatment can achieve as much weight loss in obese outpatients over 16 weeks as has been reported for the most successful drug treatment, but compliance with the prescribed diet is poor unless the diet is novel and simple.

Key messages

Energy reducing diets often work poorly in obese outpatients, although they are effective for inpatients

In this study patients put on a milk only diet had significant weight loss

Weight loss was comparable with that achieved by drugs

Patients are more likely to respond to a simple diet which they have not tried before than to advice on conventional diets

Introduction

Outpatient dietary weight reduction for obesity is unsatisfactory,1,2 but inpatient dieting is extremely effective.3 Obese patients lose weight more rapidly as inpatients than as outpatients when nominally on the same diet, which can be explained only by compliance.4 Some of the most impressive weight losses achieved by outpatient dietary treatment have been in the placebo control arm of drug trials.5,6 The ambience of a controlled drug trial seems to be conducive to high compliance with dietary treatment and hence good weight loss. The patient is reviewed regularly and believes that the treatment is something novel which may succeed.

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that prescription of simple, novel diets would result in higher levels of compliance and weight loss in an outpatient setting over 16 weeks. Patients were randomised to one of three diets, each of which was designed to produce an initial energy deficit of 4-7 MJ a day.

Subjects and methods

Recruitment and randomisation

All new patients aged over 17 attending an obesity outpatient clinic at St Bartholomew’s Hospital between 1 November 1993 and 13 May 1994 were eligible if their body mass index (weight (kg)/(height (m)2) was >27 and they were not diabetic, pregnant, or lactating. Eligibility was assessed by JSG, who was blind to the subsequent allocation of treatment.

All patients had their weight and height measured by the clinic nurse and were given appointments to return to the clinic every four weeks for 16 weeks. At the first visit JSG took a medical history and did a physical examination. CDS then performed the initial randomisation, gave dietary advice, and explained how to record dietary intake. Randomisation was achieved by using blocks of six sealed, opaque envelopes (equal allocation) from which sequential patients chose one. Exact blocking was disturbed because a partly used block of envelopes was mislaid. At subsequent visits patients were seen by JSG, and CDS and CW reviewed the food records and provided advice about the diet. CW administered psychological rating scales and a questionnaire (results not reported).

Interventions

Energy free fluid intake was unrestricted in all diets.

Control

—A conventional balanced diet composed of a variety of normal foods designed to supply about 3.4 MJ daily with at least 36 g protein.

Milk only

—A variable combination of full cream or semi-skimmed milk and unsweetened yoghurt to provide the energy equivalent of the control diet. This diet was novel and simple but very restrictive.

Milk plus

—This was the milk only diet with the addition of an unlimited amount of a single food selected by the patient on each day of the week. Of these seven extra foods, three were a fruit or vegetable, two were a high protein food, and two were a “favourite” food. The seven foods were repeated on the same day of successive weeks. It was intended to give the patient greater power to decide the nature of the diet without greatly affecting its nutritional characteristics. On average, this diet supplied 5.6 MJ.

Statistical analysis

We performed an intention to treat analysis (using last available weight) and an analysis of patients attending at both week 4 and 16. Confidence intervals are based on t tests, assuming unequal variances for comparisons. Mann-Whitney tests, performed because positive skew was introduced in the intention to treat analysis, did not alter significance; means are presented for simplicity.

Results

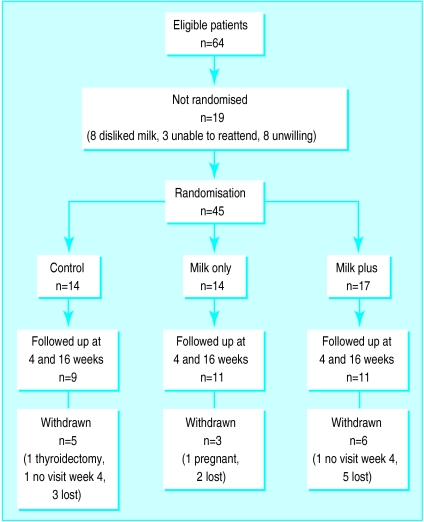

Sixty four patients met the criteria for the trial (figure). After the protocol was explained 19 patients declined to be randomised, leaving 45 patients. Baseline characteristics were similar in the three groups (table1) and a similar proportion in each group completed the trial. The table shows the weight loss from baseline at four and 16 weeks and table 2 shows the mean differences between the groups.

Table 2.

Mean difference (95% confidence interval) in weight loss between patients randomised to control, milk only, and milk plus diets. Results shown for all randomised patients (intention to treat analysis) and for those completing trial

| Milk only v control

|

Milk plus v milk only

|

Milk plus v control

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised | Completed | Randomised | Completed | Randomised | Completed | |||

| 4 weeks | 5.5 (3.1 to 7.9) | 6.1 (3.2 to 8.9) | −3.6 (−6.0 to −1.1) | −3.1 (−5.6 to −0.6) | 1.9 (−0.3 to 4.1) | 2.9 (−0.2 to 6.1) | ||

| 16 weeks | 7.7 (3.8 to 11.6) | 8.6 (4.2 to 12.9) | −2.4 (−7.7 to 2.9) | −3.0 (−8.7 to 2.7) | 5.3 (0.7 to 9.9) | 5.6 (0.0 to 11.1) | ||

Discussion

This trial was a realistic test of what can be achieved by dietary treatment alone for obese patients in NHS facilities. The patients were typical of those referred by general practitioners to a hospital obesity clinic7: they travelled to the clinic at their own expense, neither paid nor received money, and bought the food they ate at normal retail outlets. No drug or surgical treatment was offered and no exercise or behavioural therapy programmes were provided.

Within the limitations of a trial lasting only 16 weeks our results support the received wisdom that “diets do not work,” at least as far as the conventional balanced reducing diet is concerned. The milk only diet was simple and patients had not tried it before. Patients completing the trial in this group achieved the highest overall mean weight loss (11.2 kg in 16 weeks), which is greater than the mean weight loss in one year in trials of dexfenfluramine,8 sibutramine,9 or orlistat.10,11 Patients consuming only milk might be expected to become deficient in some vitamins and iron, but this was not found in another longer trial4; constipation was the only serious side effect reported.

We expected that patients on the milk plus diet would have a greater weight loss than those on the milk only diet as it was still simple but much less boring and patients were more likely to comply with it. The milk plus diet is also theoretically superior as it provides a greater variety of nutrients and an energy deficit of about 4 MJ/day instead of a 7 MJ/day deficit on milk only, which would cause an excessive loss of lean tissue.4 Analysis of compliance (not reported) showed that it was similar for the two milk diets but much lower for the conventional diet.

We are not advocating milk only as a general long term reducing diet for obese outpatients, because in the long term it will cease to be novel and compliance will fall. Probably the best strategy is to rotate diets, just as rotation of anorectic drugs achieves greater long term weight loss than continuous use of a single drug.12

Figure.

Randomisation and follow up of patients in trial

Table 1.

Mean (SD) baseline characteristics and weight loss of patients who were randomised to control, milk only, and milk plus diets. Results shown for all randomised patients (intention to treat analysis) and for those completing trial

| Group | Control

|

Milk only

|

Milk plus

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised (n=14) | Completed (n=9) | Randomised (n=14) | Completed (n=11) | Randomised | Completed (n=11) | |||

| (n=17) | ||||||||

| Sex (M/F) | 3/11 | 1/8 | 3/11 | 2/9 | 4/13 | 3/8 | ||

| Age (years) | 39.5 (13.9) | 38.1 (15.0) | 45.2 (14.8) | 46.0 (14.3) | 41.1 (11.5) | 41.4 (13.4) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 122 (38) | 118 (33) | 116 (17) | 114 (17) | 129 (26) | 127 (28) | ||

| Body mass index | 43.0 (9.2) | 41.4 (9.0) | 43.1 (7.7) | 42.6 (8.1) | 46.6 (9.1) | 44.9 (9.3) | ||

| Weight loss at 4 weeks (kg) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.9 (2.7) | 1.4 (3.4) | 6.4 (3.5) | 7.4 (2.4) | 2.8 (3.3) | 4.3 (3.2) | ||

| Range | −3.7 to 7.9 | −3.7 to 7.9 | 0.0 to 11.5 | 3.3 to 11.5 | −0.7 to 10.5 | −0.7 to 10.5 | ||

| Weight loss at 16 weeks (kg) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (3.5) | 2.6 (4.1) | 9.4 (6.1) | 11.2 (5.2) | 7.0 (8.4) | 8.2 (7.4) | ||

| Range | −0.9 to 10.7 | −0.9 to 10.7 | −0.4 to 18.6 | −0.4 to 18.6 | 0.0 to 25.6 | −0.7 to 24.5 | ||

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Obesity in Scotland. Edinburgh: SIGN, Royal College of Physicians; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glenny A-M, O’Meara S, Melville A, Sheldon TA, Wilson C. The treatment and prevention of obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Obes. 1997;21:715–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bortz WM. A 500 pound weight loss. Am J Med. 1969;47:325–331. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(69)90159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrow JS, Webster JD, Pearson M, Pacy PJ, Harpin G. Inpatient-outpatient randomised comparison of Cambridge diet versus milk diet in 17 women over 24 weeks. Int J Obes. 1989;13:521–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Outpatient treatments of obesity: a comparison of methodology and clinical results. Int J Obes. 1979;3:261–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray GA. Coherent preventive and management strategies for obesity. In: Chadwick DJ, Cardew G, editors. The origins and consequences of obesity. CIBA symposium 201. Chichester: Wiley; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garrow JS. Obesity and related diseases. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guy-Grand B, Apfelbaum M, Crepaldi G, Gries A, Lefebvre P, Turner P. International trial of long-term dexfenfluramine in obesity. Lancet. 1989;ii:1142–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lean MEJ. Sibutramine—a review of clinical efficacy. Int J Obes. 1997;21(suppl 1):S30–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James WPT, Avenell A, Broom J, Whitehead J. A one-year trial to assess the value of orlistat in the management of obesity. Int J Obes. 1997;21(suppl 3):S24–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjostrom L, Rissanen A, Andersen T, Boldrin M, Golay A, Koppeschaar HPF, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial or orlistat for weight loss and prevention of weight regain in obese patients. Lancet. 1998;352:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub M. Long term weight control study: conclusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:642–646. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]