Abstract

Transgenic mouse models with nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) knockouts and knockins have provided important insights into the molecular substrates of addiction and disease. However, most studies of heterologously expressed neuronal nAChR have used clones obtained from other species, usually human or rat. In this work, we use mouse clones expressed in Xenopus oocytes to provide a relatively comprehensive characterization of the three primary classes of nAChR: muscle-type receptors, heteromeric neuronal receptors, and homomeric α7-type receptors. We evaluated the activation of these receptor subtypes with acetylcholine and cytisine-related compounds, including varenicline. We also characterized the activity of classic nAChR antagonists, confirming the utility of mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine as selective antagonists in mouse models of α3β4 and α4β2 receptors, respectively. We also conducted an in-depth analysis of decamethonium and hexamethonium on muscle and neuronal receptor subtypes. Our data indicate that, as with receptors cloned from other species, pairwise expression of neuronal α and β subunits in oocytes generates heterogeneous populations of receptors, most likely caused by variations in subunit stoichiometry. Coexpression of the mouse α5 subunit had varying effects, depending on the other subunits expressed. The properties of cytisine-related compounds are similar for mouse, rat, and human nAChR, except that varenicline produced greater residual inhibition of mouse α4β2 receptors than with human receptors. We confirm that decamethonium is a partial agonist, selective for muscle-type receptors, but also note that it is a nondepolarizing antagonist for neuronal-type receptors. Hexamethonium was a relatively nonselective antagonist with mixed competitive and noncompetitive activity.

Biomedical research is motivated largely by the desire to understand human diseases and develop therapeutic approaches for the treatment of those diseases. To those ends, animal models are frequently used, to both understand basic biology and determine the pharmacological potential of new drugs. In recent decades, research with in vivo animal models and acute ex vivo preparations has been supplemented, and in some cases largely replaced, by in vitro approaches, such as tissue culture models or heterologous expression systems. Both tissue culture and heterologous expression offer the advantage that the cells or molecules studied may be human in origin, obviating the concern that there may be species differences in the effects of drugs intended for human therapeutics. However, neither tissue culture nor heterologous expression systems are likely to provide adequate context to model disease states. Disease models still most often require whole-animal studies.

In the past 50 years biomedical research has relied primarily on rodent models, with the rat representing the most common rodent model. However, the number of mouse studies relative to rat studies has increased significantly since 1980, because the recent genesis of valuable transgenic mouse lines has provided important new disease models (Marubio and Changeux, 2000).

Transgenic mice have been very useful for nicotinic receptor research (Marubio and Changeux, 2000), with multiple strains of knockout mice allowing us to ask important probative questions regarding the molecular substrates of nicotine addiction and the appropriate molecular targets for potential therapeutics (Champtiaux and Changeux, 2004). Ironically, although one would expect that studies with knockout animals would go hand in glove with studies of heterologously expressed receptors, most studies of heterologously expressed neuronal nAChR have used cDNAs cloned from rats, humans, or chickens (Hussy et al., 1994; Zwart et al., 2006; Papke et al., 2008). Very few studies of neuronal nAChR have used mouse receptor clones, although many studies of muscle-type nAChR have used the embryonic form of the mouse receptor, because of the early cloning of those genes from the BC3H1 cell line (Patrick et al., 1987).

There are three broad classes of nAChR subtypes, all of which can function as ligand-gated cation channels (Millar and Gotti, 2009). The first nAChRs to be isolated and well studied were those expressed by muscle cells. They are pentamers with the subunit composition α1β1γδ in embryonic muscle (with two α1 subunits in each pentamer). In adult muscle an ε subunit substitutes for the γ. A second class of heteromeric nAChRs includes those expressed in neurons that contain specialized α subunits (α2, α3, α4, or α6) and non-α subunits (β2 or β4), sometimes coexpressed with the accessory subunits α5 or β3. In the heteromeric receptors of autonomic (i.e., ganglionic) neurons the primary α subunit is α3, whereas in the rodent central nervous system (CNS) the primary α subunit is α4. The third class of nAChR is considered ancestral, because those nAChRs function as homopentamers with only α subunits (usually α7). Such α7-type receptors are expressed by both neurons and some non-neuronal cell types, such as cells in the immune system (de Jonge and Ulloa, 2007).

In the present study, we present an analysis of the acetylcholine (ACh)-evoked activation of the three classes of mouse nAChR. We also characterized the effects of the cytisine derivative varenicline (Rollema et al., 2007), the most recently approved drug for the treatment of nicotine dependence, and compared its effects with the parent compound cytisine and the recently reported cytisine derivative 3-pyr-Cyt (Mineur et al., 2009) on important mouse neuronal nAChR subtypes. We further extend our studies to provide a comprehensive characterization of the putative neuromuscular blocker decamethonium (Paton and Zaimis, 1949) and the classical ganglionic blocker hexamethonium by using heterologously expressed mouse nAChR (Paton and Perry, 1953).

Materials and Methods

Preparation of RNA.

The mouse muscle α1, β1, γ, and δ nAChR clones were obtained from Dr. Jim Boulter (University of California, Los Angeles, CA), and the mouse muscle ε clone was from Paul Gardner (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA). The human α4, β2, and α5 clones, and the β2–6-α4 concatamer, were provided by Jon Lindstrom (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA). The cDNAs for mouse α3, α4, α5, α7, β2, and β4 were cloned as reported previously (Stitzel et al., 1996, 2001; Azam et al., 2005).

After linearization and purification of cloned cDNAs, RNA transcripts were prepared in vitro by using the appropriate mMessage mMachine kit from Ambion (Austin, TX).

Expression in Xenopus Oocytes.

Mature (>9 cm) female Xenopus laevis African frogs (Nasco, Fort Atkinson, WI) were used as a source of oocytes. Before surgery, the frogs were anesthetized by placing the animal in a 1.5g/l solution of MS222 for 30 min. Oocytes were removed from an incision made in the abdomen.

To remove the follicular cell layer, harvested oocytes were treated with 1.25 mg/ml type 1 collagenase (Worthington Biochemicals, Freehold, NJ) for 2 h at room temperature in calcium-free Barth's solution [88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.33 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 12 mg/l tetracycline chloride]. Subsequently, stage 5 oocytes were isolated and injected with 50 nl (5–20 ng) of each of the appropriate subunit cRNAs. The RNAs injected for αβ pairs were injected at a 1:1 ratio, and when α5 was included with an αβ pair, the RNAs were injected at a 1:1:1 ratio. Recordings were made 1 to 10 days after injection.

Chemicals.

Varenicline was provided by Targacept (Winston Salem, NC), and 3-pyr-Cyt (Mineur et al., 2009) was provided by Daniela Guendisch (University of Hawaii, Hilo, HI). All other chemicals for electrophysiology were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Fresh ACh stock solutions were made daily in Ringer's solution and diluted.

Electrophysiology.

Experiments were conducted by using OpusXpress 6000A (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). OpusXpress is an integrated system that provides automated impalement and voltage clamp of up to eight oocytes in parallel. Cells were automatically perfused with bath solution, and agonist solutions were delivered from a 96-well plate. Both the voltage and current electrodes were filled with 3 M KCl. The agonist solutions were applied via disposable tips, which eliminated any possibility of cross-contamination. Drug applications alternated between ACh controls and experimental applications. Flow rates were set at 2 ml/min for experiments with α7 receptors and 4 ml/min for other subtypes. Cells were voltage-clamped at a holding potential of −60 mV. Data were collected at 50 Hz and filtered at 20 Hz. ACh applications were 12 s in duration followed by 181-s washout periods with α7 receptors and 8 s in duration with 241-s washout periods for other subtypes.

Measurement of Functional Responses.

Pharmacological characterizations of ion channel responses often rely solely on the measurement of peak currents. However, with desensitizing receptors like nAChR, the peak amplitudes of agonist-evoked responses cannot be interpreted in any straightforward manner, because of their nonstationary nature. For heteromeric nAChR many factors determine peak current amplitudes, including agonist application rate, channel activation rates, desensitization, and even potentially channel block by agonist (Papke, 2009). For α7 receptors, the peak currents are associated with synchronization of channel activation that occurs well in advance of the full agonist application (Papke and Papke, 2002). Therefore, we have also measured and report the net charge of the responses to add insight into additional and important aspects of the functional responses.

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis.

Each oocyte received two initial control applications of ACh, then an experimental drug application and a follow-up control application of ACh. The specific control concentrations were chosen because they gave robust, reproducible responses that did not show significant rundown or cumulative desensitization with repeated applications. The control ACh concentrations for mouse α1β1γδ, α1β1εδ, α4β2, α3β2, α3β4, α3β2α5, α3β4α5, α4β2α5, and α7 receptors were 30, 3, 10, 100, 100, 100, 100, 10, and 100 μM, respectively. These concentrations represented the EC90, EC4, EC20, EC50, EC60, EC25, EC60, EC20, and EC100 values for each of the receptors, respectively (measured for net charge for α7 and peak current for all others). For the human high-sensitivity (HS) α4β2 [α3(2)β2(3)], low-sensitivity (LS) α4β2 [α3(3)β2(2)], and α4β2α5 receptors, the control ACh concentrations were 10, 100, and 10 μM, respectively. These represented the peak current EC100, EC50, and EC60 values for each of the receptors, respectively.

Responses to each drug application were calculated relative to the preceding ACh control responses to normalize the data, compensating for the varying levels of channel expression among the oocytes. Drug responses were initially normalized to the ACh control response values and then adjusted to reflect the experimental drug responses relative to the ACh maximums. Responses were calculated as both the peak current amplitudes and net charge (Papke and Papke, 2002). Means and standard errors were calculated from the normalized responses of at least four oocytes for each experimental concentration. Because the application of some experimental drugs cause the subsequent ACh control responses to be reduced because of some form of residual inhibition (or prolonged desensitization), subsequent control responses were compared with the preapplication control ACh responses. When cells failed to recover to at least 75% of the previous control they were discarded and new cells were used.

For concentration-response relations, data derived from net charge analyses were plotted by using Kaleidagraph 3.0.2 (Abelbeck Software, Reading, PA), and curves were generated from the Hill equation:

where Imax denotes the maximal response for a particular agonist/subunit combination, and n represents the Hill coefficient. Imax was constrained to equal 1 for the ACh responses, because we used the maximal ACh responses to define full agonist activity. Negative Hill slopes were applied for the calculation of IC50 values associated with inhibition.

Results

ACh Activation

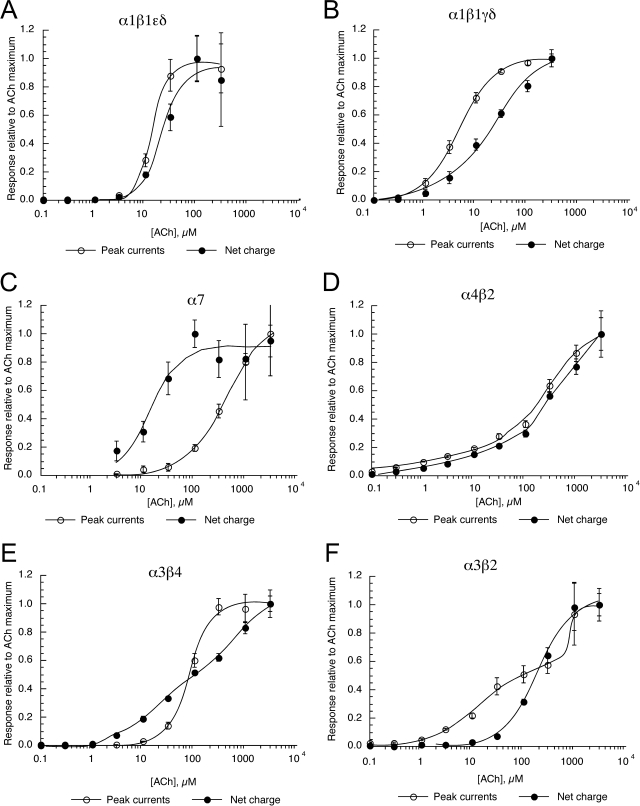

Shown in Fig. 1 are concentration-response studies for ACh activation of the two subtypes of mouse muscle nAChR, the adult form (α1β1εδ) and the embryonic form (α1β1γδ), α7 homopentamers, and the pairwise combinations of neuronal α and β subunits, α4β2, α3β4, and α3β2. Data were analyzed for both peak currents and net charge. Because ACh is our reference agonist, for all plots in Fig. 1, the Imax was constrained to equal one.

Fig. 1.

Concentration-response studies for mouse muscle and neuronal nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A, α1β1εδ. B, α1β1γδ. C, α7. D, α4β2. E, α3β4. F, α3β2. Data were obtained by alternating applications of ACh at fixed control concentrations (see Materials and Methods) and ACh at increasing concentrations. The control responses were relatively consistent throughout the entire range of test concentrations. Test responses were initially normalized relative to the ACh controls, and the data are expressed relative to the observed ACh maximum responses. Data were calculated for both peak current and net charge as described (Papke and Papke, 2002). Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

For the adult muscle receptor, the ACh concentration-response curves (CRCs) were nearly overlapping, whereas for the embryonic form of the receptor the net charge curve was shifted to the right.

The mouse heteromeric neuronal nAChR showed a tendency toward having ACh CRCs that were best-fit by two components, consistent with the recent distinction made between HS and LS forms of α4β2 nAChR of other species (Nelson et al., 2003; Moroni et al., 2006) and efflux studies with mouse brain tissues (Grady et al., 2009). Whereas α4β2 receptors had nearly overlapping peak current and net charge response curves, the same was not true for the α3-containing receptors. The population of α3β2 receptors with higher sensitivity to ACh seemed to contribute relatively little to the net charge concentration-response data. In contrast, putative HS α3β4 receptors appeared to have small peak currents but contributed relatively large amounts of net charge. The EC50 values for ACh activation of mouse nAChR are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

EC50 values for ACh activation of mouse nAChR (see Fig. 1)

| Receptor | Peak Current | Net Charge | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| α1β1εδ | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 21.7 ± 3.1 | 1.60 |

| α1β1γδ | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 22.9 ± 4.6 | 4.98 |

| α4β2(HS) | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.4 ± 3.3 | 1.75 |

| α4β2(LS) | 320 ± 66 | 560 ± 220 | 1.75 |

| α3β2(HS) | 15 ± 5 | 200 ± 14 | 13.3 |

| α3β2(LS) | 760 ± 1700 | 200 ± 14 | 0.263 |

| α3β4(HS) | 79 ± 6 | 17 ± 10 | 0.215 |

| α3β4(LS) | 79 ± 6 | 1200 ± 790 | 15.2 |

| α7 | 450 ± 37 | 13.3 ± 3.7 | 0.03 |

| α3β2+α5(HS) | 22 ± 37 | 29 ± 33 | 1.30 |

| α3β2+α5(LS) | 987 ± 86 | 651 ± 95 | 0.66 |

| α3β4+α5 | 80 ± 5 | 120 ± 5 | 1.50 |

| α4β2+α5(HS) | 1.2 ± 3.6 | 4.3 ± 4.3 | 3.6 |

| α4β2+α5(LS) | 231 ± 48 | 321 ± 25 | 1.38 |

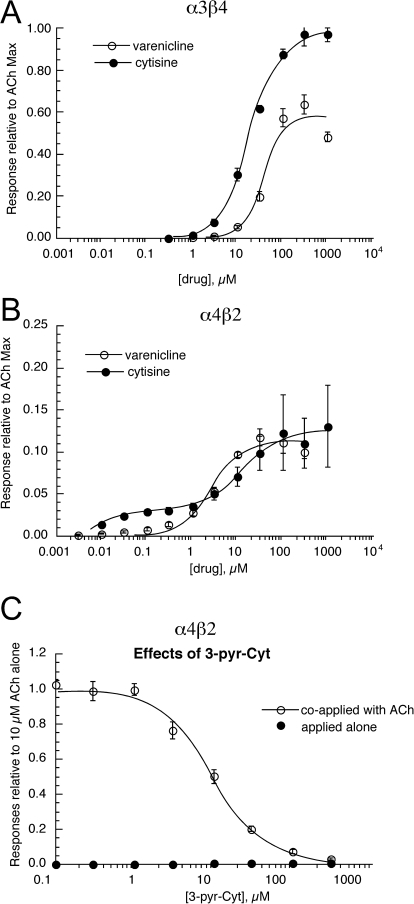

The Effects of Cytisine and Related Compounds

We evaluated the effects of cytisine and two cytisine derivatives, the antismoking drug varenicline (Coe et al., 2005) and the recently reported novel compound 3-pyr-Cyt (Mineur et al., 2009) on mouse neuronal nAChR. Peak current data are presented in Fig. 2. Similar results were obtained with the analysis of net charge (not shown). As reported for other species (Table 2), both cytisine and varenicline were effective activators of α3β4 receptors (Fig. 2A), with cytisine being both the most potent and most efficacious of the two. Likewise, both varenicline and cytisine were relatively weak partial agonists of mouse α4β2 nAChR, with maximal efficacies less than 15% that of ACh (Fig. 2B). Like ACh, the cytisine responses of α4β2 receptors were best-fit to a two-site model, whereas varenicline seemed to only work in a single concentration range, suggesting a potential selectivity for LS over HS α4β2 receptors in mice.

Fig. 2.

The effects of cytisine and related compounds on mouse neuronal nAChRs. A and B, data were obtained by alternating applications of ACh at fixed control concentrations (see Materials and Methods) and either cytisine or varenicline at increasing concentrations to cells expressing either mouse α3β4 (A) or α4β2 (B) subunits. Data shown are for the peak current responses normalized to the extrapolated maximum ACh responses for the different receptor subtypes. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of at least four oocyte responses. C, the effects of the cytisine derivative 3-pyr-Cyt on mouse α4β2 receptors, either applied alone or coapplied with ACh. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

TABLE 2.

The effects of cytisine and derivates on neuronal nAChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes

| Species | Receptor | EC50 | IC50 | Imax | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||||

| Cytisine | |||||

| Rat | α4β2 | ≈3 | 0.14 | Papke and Heinemann, 1994 | |

| Human | HS α4β2 | <0.05 | Mineur et al., 2009 | ||

| Mouse | α4β2(HS)1 | 2 | 0.08 | ||

| Human | LS α4β2 | 13 | 0.1 | Mineur et al., 2009 | |

| Mouse | α4β2(LS) | 13 | 0.04 | ||

| Rat | α3β4 | N.D.2 | ≥1.0 | Papke and Heinemann, 1994 | |

| Mouse | α3β4 | 20 | 1.0 | ||

| Rat | α3β2 | 0.025 | Papke and Heinemann, 1994 | ||

| Mouse | α3β2 | <0.02 | |||

| Rat | α7 | 13 | 0.73 | Papke and Papke, 2002 | |

| Human | α7 | 14 | 0.90 | Papke and Papke, 2002 | |

| Mouse | α7 | 70 | 1.0 | ||

| Varenicline | |||||

| Rat | α4β2 | 2.2 | 0.13 | Mihalak et al., 2006 | |

| Human | HS α4β2 | 0.1 | 0.13 | ||

| Human | LS α4β2 | 6 | 0.08 | ||

| Mouse | α4β2 | 2.6 | 0.11 | ||

| Rat | α3β4 | 55 | 0.75 | Mihalak et al., 2006 | |

| Mouse | α3β4 | 37 | 0.58 | ||

| Rat | α3β2 | <0.10 | Mihalak et al., 2006 | ||

| Mouse | α3β2 | <0.03 | |||

| Rat | α7 | 183 | 0.93 | Mihalak et al., 2006 | |

| Human | α7 | 2.4 | 1.2 | ||

| Mouse | α7 | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||

| 3-pyr-Cyt | |||||

| Human | HS α4β2 | 12 | 0.08 | Mineur et al., 2009 | |

| Human | LS α4β2 | 31 | 0.03 | Mineur et al., 2009 | |

| Mouse | α4β2 | <0.01 | |||

| Mouse | α3β4 | <0.01 | |||

| Mouse | α3β2 | <0.01 | |||

| Human | α7 | >100 | ≈0.20 | Mineur et al., 2009 | |

| Mouse | α7 | >3000 | ≈0.94 | ||

| Inhibition by 3-pyr-Cyt | |||||

| Human | α4β2 | 60 | Mineur et al., 2009 | ||

| Mouse | α4β2 | 10 | |||

Data without specific references were obtained as part of the current study.

The designations HS α4β2 and LS α4β2 indicate receptors with defined subunit composition formed by the coexpression of either α4 or β2 with linked α4 β2 concatamers. The designations α4β2(HS) and α4β2(LS) indicate that data were obtain from a mixed receptor populations that were best-fit with a two-site model.

Not determined, because a full concentration-response study was not conducted.

Likely an underestimate of potency because data are based on peak current rather than net charge.

Estimated as described previously (Papke, 2006).

Although with our standard 5-min washout period, the ACh responses of cells expressing mouse α4β2 receptors recovered readily after the applications of cytisine throughout the concentration range studied, after the application of varenicline at concentrations ≥1 μM, subsequent responses to ACh were greatly reduced in a concentration-dependent manner. This residual inhibition of mouse α4β2 receptors was significantly greater than when varenicline was applied to cells expressing human α4β2 receptors in the same manner (i.e., by expressing α4 and β2 cRNAs at a 1:1 ratio). This was determined by exposing cells expressing either mouse α4β2 or human α4β2 receptors to two applications of 30 μM ACh before the application of varenicline, followed by further applications of 30 μM ACh. After the application of 1 μM varenicline, the peak current responses of mouse α4β2 receptors were reduced to only 29 ± 6% of the initial controls, whereas human α4β2 receptor responses were significantly larger (p < 0.05), 61 ± 7% of the initial controls (data not shown). In contrast, after the application of 10 μM varenicline, the peak current responses of mouse α4β2 receptors were further reduced to only 7 ± 1% of the initial controls, whereas human α4β2 receptor responses were significantly (p < 0.0001) larger, 44 ± 22% of the initial controls. Similar differences were seen in the net charge measurements (not shown). These results suggest that the effects of varenicline may be similar to those of mouse and human nAChR during acute applications, but with prolonged treatments, varenicline may be more effective at down-regulating mouse α4β2 nAChR than human α4β2 nAChR.

As expected, both varenicline and cytisine were efficacious activators of mouse α7 receptors (Table 2; data not shown). Varenicline was a very potent full agonist at mouse α7 receptors, with an EC50 of 0.8 μM. However, the potency of cytisine for mouse α7 receptors was less than previously reported for rat and human α7 receptors (Table 2).

Like what has been reported for human receptors, 3-pyr-Cyt was able to activate mouse α7 receptors at very high concentrations. When applied at 1 mM, it evoked a net charge response that was 40 ± 15% of the ACh maximum. At this concentration, the peak currents were only approximately 12% the ACh maximum, indicative of very low potency activation. We estimate that although the efficacy of 3-pyr-Cyt, extrapolated to higher concentrations than we normally test, might be as high as 80 to 100% that of ACh, the EC50 would be >3 mM, 40-fold higher than that of cytisine.

Neither cytisine nor the other two related compounds produced detectable levels of activation of mouse α3β2 receptors (not shown). The cytisine derivative 3-pyr-Cyt (Mineur et al., 2009) was also ineffective at the other heteromeric mouse neuronal nAChR tested, as evidenced by no currents generated above our reliable level of detection (approximately 1% ACh maximum). Although 3-pyr-Cyt was not an effective activator of human α4β2 receptors expressed in oocytes, it was able to inhibit ACh-evoked responses when coapplied with ACh. Similar results were obtained with mouse α4β2 receptors (Fig. 2C), with an inhibition of ACh-evoked responses approximately 6-fold more potent (Table 2) than previously reported for human α4β2 receptors (Mineur et al., 2009).

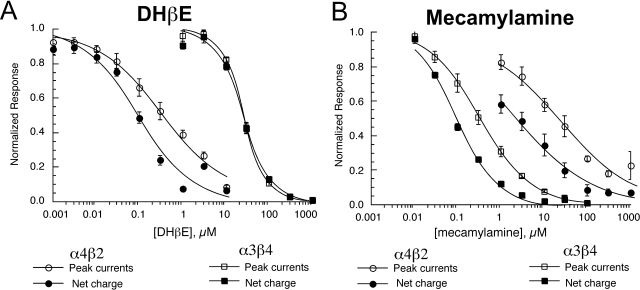

Effects of the Neuronal Nicotinic Antagonists Mecamylamine and Dihydro-β-Erythroidine

Mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE) are commonly used neuronal nAChR antagonists. Previous studies using rat nAChR clones (Papke et al., 2008) showed the noncompetitive antagonist mecamylamine to have a selectivity for rat β4-containing nAChR, whereas DHβE, a competitive antagonist, was selective for α4-containing receptors (Papke et al., 2008). To confirm whether this distinction would hold for mouse nAChR, we tested DHβE and mecamylamine over a range of concentrations by using cells expressing mouse α3β4 or α4β2 receptors. As shown in Fig. 3, the effects of DHβE and mecamylamine on the mouse receptors compare well with previous results obtained with rat α4β2 and α3β4 nAChR. With the exception of DHβE inhibition of α3β4, the IC50 values for the inhibition of net charge were lower than for peak current (Table 3). Our data indicate that DHβE was 70- to 300-fold (based on inhibition of peak currents and net charge, respectively) more potent for the inhibition of α4β2 receptors than for α3β4 receptors, not unlike the 260-fold potency difference reported for the inhibition peak currents for rat α4β2 relative to α3β4 receptors (Papke et al., 2008). Mecamylamine was 63- to 23-fold more potent for the inhibition of mouse α3β4 receptors than for α4β2 receptors (based on inhibition of peak currents and net charge, respectively), a potency difference much greater than the 9.2-fold difference reported for the inhibition of peak currents for the corresponding rat receptors (Papke et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Inhibition of mouse α4β2 and α3β4 receptors by DHβE (A) and mecamylamine (B). Data were obtained by alternating applications of ACh at fixed control concentrations (see Materials and Methods) and ACh with increasing concentrations of antagonist. The control responses were relatively consistent throughout the entire range of test concentrations, and the data were normalized relative to the control responses to ACh applied alone. Data were calculated for both peak current and net charge. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

TABLE 3.

Selectivity of mecamylamine and DHβE for the inhibition of α3β4 and α4β2 receptors

| IC50 values |

||

|---|---|---|

| Mecamylamine | DHβE | |

| μM | ||

| α4β2 Peak | 21 ± 4 | 0.38 ± 0.04 |

| α4β2 Charge | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| α3β4 Peak | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 25 ± 1 |

| α3β4 Charge | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 25 ± 2 |

Effects of Decamethonium and Hexamethonium

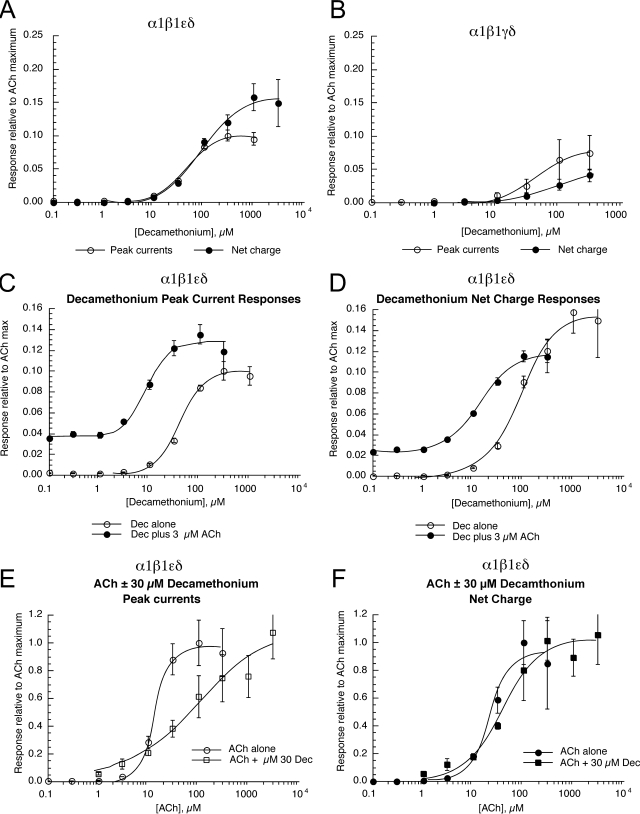

Selective Partial Agonism of Muscle-Type nAChR by Decamethonium.

Decamethonium has been reported to be a depolarizing blocker of the neuromuscular junction (Paton and Zaimis, 1949). Therefore, we conducted concentration-response studies of the two forms of mouse muscle receptors to determine whether decamethonium was a partial agonist for these receptors (Fig. 4, A and B). The data indicate that for α1β1εδ receptors decamethonium has an efficacy approximately 10% that of ACh for peak currents and 15% that of ACh for net charge with EC50 values of 40 ± 3 and 86 ± 10 μM, respectively. For α1β1γδ receptors, decamethonium has an efficacy approximately 8% that of ACh for peak currents and 5% for net charge with EC50 values of 44 ± 6 and 89 ± 8 μM, respectively. Decamethonium did not evoke any detectable responses from any of the neuronal nAChR subtypes (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Decamethonium and ACh interactions on mouse muscle-type receptors. A and B, the concentration-response results for decamethonium activation of α1β1εδ (adult type) (A) or α1β1γδ (fetal) (B) muscle-type receptors, expressed relative to the extrapolated ACh maximal peak current or net charge responses. C–F, the peak current (C) and net charge (D) responses of cells expressing α1β1εδ receptors to 3 μM ACh coapplied with increasing concentrations of decamethonium compared with the responses to decamethonium alone (taken from A), and the peak current (E) and net charge (F) responses of cells expressing α1β1εδ receptors to increasing concentrations of ACh coapplied with 30 μM decamethonium (Dec) compared with the responses to ACh alone (taken from Fig. 1A). Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

The effects of decamethonium on α1β1εδ-expressing cells were studied in further detail (Fig. 4, C–F). Figure 4, C and D, shows plots of the responses to 3 μM ACh plus decamethonium compared with the responses to decamethonium alone, normalized to ACh maximum responses. When increasing concentrations of decamethonium were coapplied with 3 μM ACh to cells expressing mouse α1β1εδ receptors, responses were obtained that were up to four to five times larger than the responses to 3 μM ACh alone (3 μM ACh being a relatively low effective concentration for the muscle-type receptor). This was consistent with decamethonium acting as a partial agonist for the muscle-type receptor.

We also conducted ACh concentration-response studies in the presence of a fixed concentration (30 μM) of decamethonium to confirm the competitive interactions between ACh and decamethonium (Fig. 4, E and F). Interestingly, there was a more notable shift in the ACh EC50 for peak currents than for net charge.

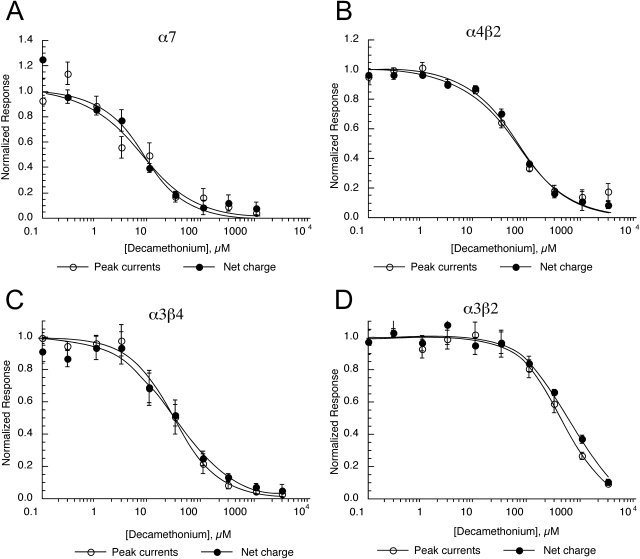

Antagonism of Neuronal nAChR by Decamethonium.

We tested the effectiveness of decamethonium as an antagonist of mouse homomeric and neuronal nAChRs. The data indicate that decamethonium was equally potent for inhibition of peak and net charge for homomeric and all of the heteromeric neuronal nAChRs (Fig. 5). Decamethonium was most potent as an antagonist of α7 receptors (Table 4). In addition, as shown in Fig. 5, decamethonium was more potent as an antagonist of α4β2 and α3β4 nAChRs than for α3β2 nAChRs. This is somewhat curious because antagonist sensitivity frequently can be related to the presence or absence of single subunits (Papke et al., 2008). For example, β4-containing receptors tend to be more sensitive to mecamylamine than β2-containing receptors, regardless of the α subunit. Likewise, α4-containing receptors tend to be more sensitive to DHβE than α3-containing receptors, regardless of the β subunit (Papke et al., 2008).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of mouse homomeric and neuronal nAChRs by decamethonium. A, α7. B, α4β2. C, α3β4. D, α3β2. Data were obtained by alternating applications of ACh at fixed control concentration (see Materials and Methods) and ACh with increasing concentrations of decamethonium. The control responses were relatively consistent throughout the entire range of test concentrations, and the data were normalized relative to the control responses to ACh applied alone. Data were calculated for both peak current and net charge. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

TABLE 4.

Inhibition of mouse neuronal nAChR by decamethonium: IC50 values for data shown in Fig. 5

| Receptor | Peak Current | Net Charge | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| α7 | 7.4 ± 2.2 | 7.8 ± 2.2 | 1.05 |

| α3β2 | 405 ± 134 | 549 ± 57 | 1.35 |

| α3β2+α5 | 925 ± 338 | 670 ± 95 | 0.72 |

| α3β4 | 28 ± 3 | 30 ± 5 | 1.07 |

| α3β4+α5 | 14.2 ± 0.5 | 17 ± 2 | 1.2 |

| α4β2 | 59 ± 11 | 64 ± 7 | 1.08 |

| α4β2+α5 | 49 ± 3 | 59 ± 7 | 1.20 |

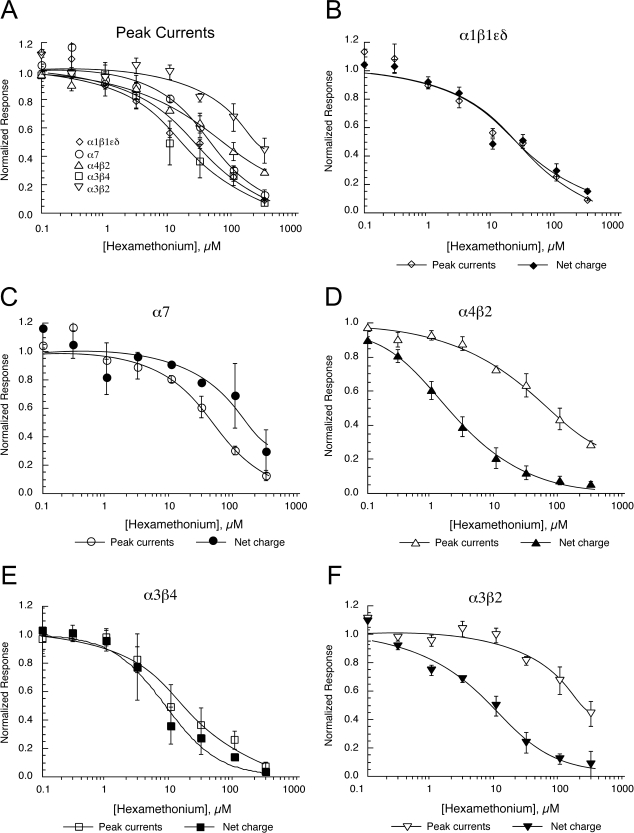

Antagonism of nAChRs by Hexamethonium.

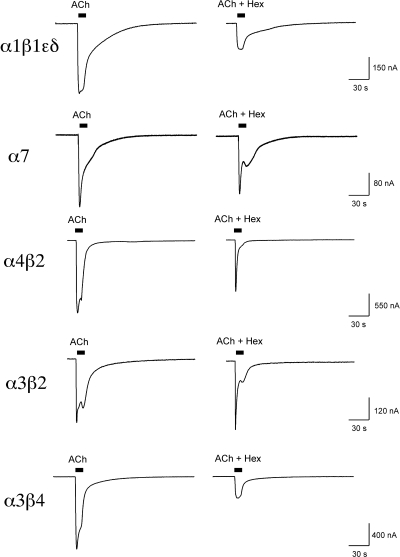

Muscle, homomeric, and neuronal heteromeric mouse receptors were tested for sensitivity to inhibition by the putative ganglionic blocker hexamethonium (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6A, the sensitivity of neuronal receptors to inhibition of peak currents by hexamethonium did not differ from that of muscle-type receptors. In fact, the peak currents of α3β2 receptors were 10-fold less sensitive to inhibition by hexamethonium than the peak currents of muscle receptors (Table 5). However, for neuronal nAChR-mediated responses, the net charge was more potently inhibited by hexamethonium than the peak current responses (Fig. 6, C–F), unlike the muscle receptor for which peak currents and net charge were inhibited similarly (Fig. 6B). The disparity between the inhibition of peak currents and net charge was most striking for β2-containing receptors (Fig. 6, D and F; see also raw data traces in Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of mouse nAChRs by hexamethonium. Data were obtained by alternating applications of ACh at fixed control concentration (see Materials and Methods) and ACh with increasing concentrations of hexamethonium. The control responses were relatively consistent throughout the entire range of test concentrations, and the data were normalized relative to the control responses to ACh applied alone. Data were calculated for both peak current and net charge. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes. A, the peak current results for all of the receptor subtypes. B–F, the results for both peak current and net charge for each of the receptor subtypes tested. B, α1β1εδ. C, α7. D, α4β2. E, α3β4. F, α3β2.

TABLE 5.

Inhibition of mouse nAChR by hexamethonium: IC50 values for data shown in Fig. 6

| Receptor | Peak Current | Net Charge | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| α1β1εδ | 21 ± 6 | 23 ± 7 | 1.05 |

| α7 | 44 ± 9 | 157 ± 54 | 3.56 |

| α3β2 | 221 ± 47 | 7.8 ± 1.6 | 0.035 |

| α3β2+α5 | 254 ± 83 | 21 ± 5 | 0.083 |

| α3β4 | 15.6 ± 2.9 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 0.551 |

| α3β4+α5 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 0.88 |

| α4β2 | 67 ± 7 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.027 |

| α4β2+α5 | 24 ± 8 | 7.7 ± 1.9 | 0.148 |

Fig. 7.

Representative raw data traces showing ACh control responses and the responses to ACh coapplied with 10 μM hexamethonium (Hex). Note the large relative effect on net charge compared with peak current with the β2-containing receptors.

Mechanistic Studies

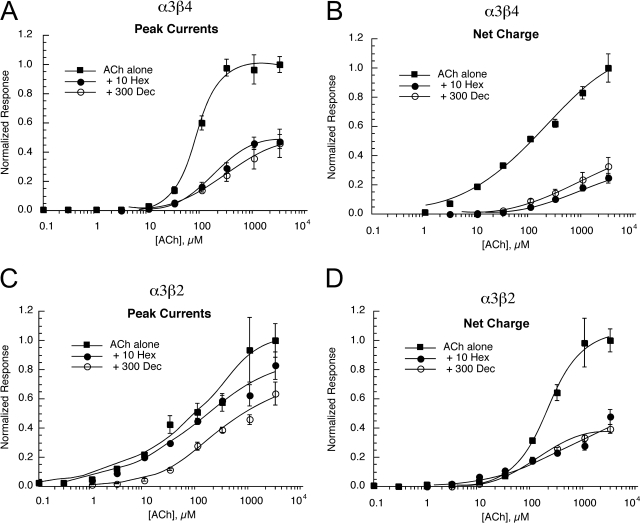

Effects of Coapplication of Antagonist on ACh CRCs.

We conducted competition experiments with both hexamethonium and decamethonium on muscle nAChR and the two pairwise subunit combinations most likely related to ganglionic receptors, α3β4 and α3β2 receptors (Fig. 8). The results, summarized in Table 6, would suggest that the inhibition of α3β2 receptors by decamethonium, and the inhibition of α1β1εδ and α3β2 receptors by hexamethonium, was noncompetitive, because there were changes in Imax without significant changes in EC50. However, the inhibition of α3β4 receptors by both drugs may be through both competitive and noncompetitive mechanisms.

Fig. 8.

Competition between hexamethonium (Hex) and decamethonium (Dec) with ACh. Shown are the peak current (A and C) and net charge (B and D) responses of cells expressing α3β4 (A and B) or α3β2 (C and D) receptors to increasing concentrations of ACh coapplied with either 10 μM hexamethonium or 300 μM decamethonium, compared with the responses to ACh alone (taken from Fig. 1). Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

TABLE 6.

Characterization of antagonist effects on ACh concentration-response curves

| Receptor | Peak Current |

Net Charge |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imax | EC50 | Imax | EC50 | |

| Decamethonium | ||||

| α1β1εδ | No change | 900% Increase | No change | 50% Increase |

| α3β2 | 30% Decrease | No effect | 60% Decrease | No effect |

| α3β4 | 45% Decrease | 500% Increase | 60% Decrease | 300% Increase |

| Hexamethonium | ||||

| α1β1εδ | 50% Decrease | No effect | 30% Decrease | No effect |

| α3β2 | 40% Decrease | No effect | 40% Decrease | 50% Increase |

| α3β4 | 50% Decrease | 120% Increase | 80% Decrease | 300% Increase |

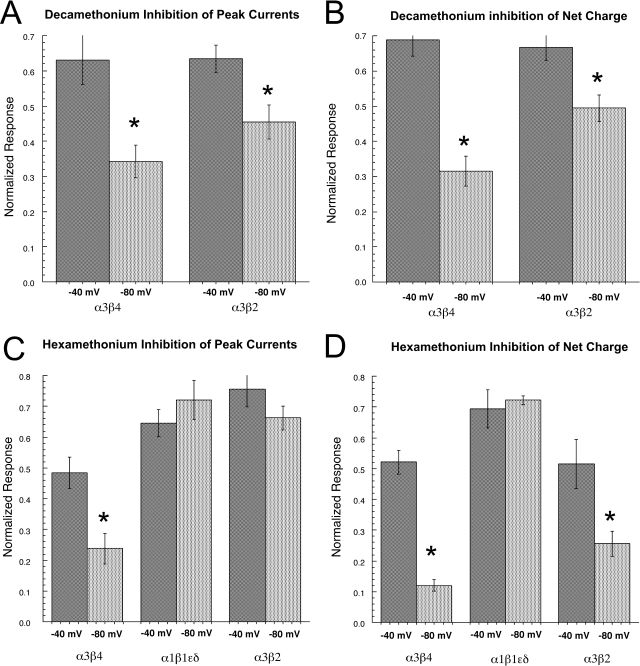

Voltage Dependence.

Because decamethonium and hexamethonium are charged molecules, if they inhibited nAChR function as channel blockers, binding to sites within the membrane electric field, then inhibition should be increased at more negative holding potentials. As shown in Fig. 9, A and B, decamethonium produced significantly more inhibition of the ganglionic homologs α3β2 and α3β4 when the cells were voltage-clamped at −80 mV than when cells were voltage-clamped at −40 mV.

Fig. 9.

Voltage dependence of the inhibitory effects of decamethonium and hexamethonium. Cells expressing mouse nAChR were tested for the inhibitory effects of 300 μM decamethonium (A and B) or 10 μM hexamethonium (C and D) at both −40 and −80 mV. Data are expressed relative to control responses to ACh alone at the same voltages. Data were calculated for both peak current and net charge. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

Although the competition experiments suggested that the inhibition of muscle-type nAChR by hexamethonium was noncompetitive (Table 6), the inhibition did not appear to be voltage-dependent (Fig. 9, C and D). In contrast, hexamethonium inhibition of the ganglionic homolog α3β4 increased with hyperpolarization for measures of both peak current and net charge, whereas increased inhibition of α3β2 receptors by hyperpolarization was apparent only for the net charge measurement.

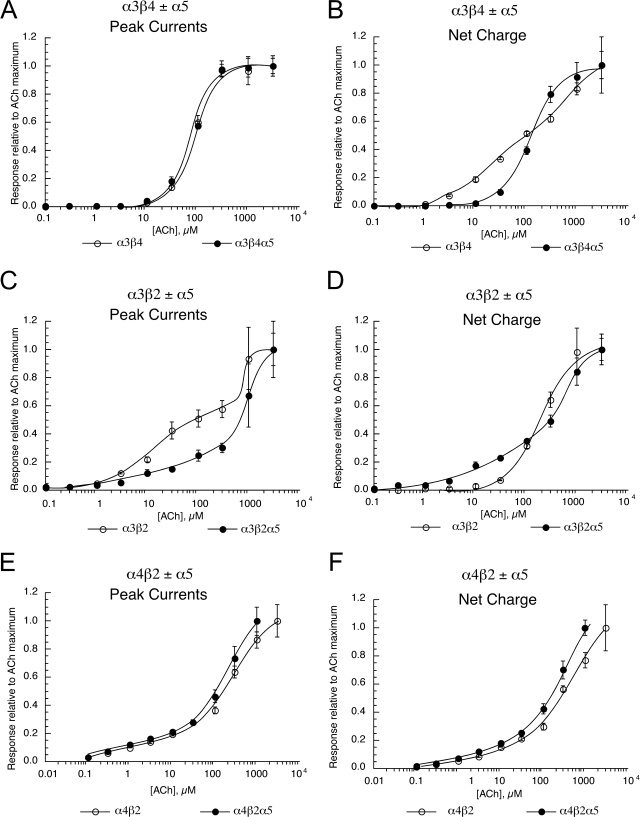

Effects of α5 Coexpression with Pairwise Combination of Mouse Neuronal nAChR.

The nicotinic α5 subunit is expressed in both the CNS and autonomic ganglia (Yu and Role, 1998; Kuryatov et al., 2008). Although α5 will coassemble with other subunits, it is not believed to form either the primary or complementary face of ligand binding domains, but rather has been hypothesized to function as a “structural” subunit (Kuryatov et al., 2008), like the β subunit of muscle-type receptors. Because α5 is not required for function, it is sometimes difficult to confirm whether it does, in fact, coassemble with other functional subunits when it is coexpressed with them. Whether there are detectable effects of α5 coexpression may depend on the expression system used, or even the species origin of the clones being used. For example, the effects of α5 coexpression are readily detectable in oocytes when human clones are used (Kuryatov et al., 2008), but not when rat clones are used (R. L. Papke, unpublished work).

We coexpressed mouse α5 subunits with either mouse α3 and β4 subunits, mouse α3 and β2 subunits, or mouse α4 and β2 subunits and measured the ACh concentration response functions. As shown in Fig. 10, α5 coexpression had marked effects on the responses of α3-containing receptors, but relatively little effect when coexpressed with α4 and β2 subunits. Coexpression of α5 with α3 and β4 did not affect ACh-evoked peak currents (Fig. 10, A and B). However, net charge was affected by the addition of the α5 subunit, which abolished the two components evident for α3β4 receptors, consistent with the hypothesis that for α3β4 receptors α5 coexpression shifted the receptor population toward a single α5-containing form.

Fig. 10.

Effects of α5 subunit coexpression with pairwise combinations of mouse nAChR subunits. ACh concentration response data are shown for mouse α3β4-containing receptors (A and B), α3β2-containing receptors (C and D), and α4β2-containing receptors (E and F) with or without the coexpression of the mouse α5 subunit. Data were calculated for both peak current (A, C, and E) and net charge (B, D, and F). Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes. Data for the receptors formed without the coexpression of α5 subunits were taken from Fig. 1.

In the case of α3β2 receptors, α5 coexpression altered both peak current and net charge. However, these CRCs remained at least as complex with the addition of the α5 subunit as with the absence of the subunit, suggesting that there may be an even more heterogeneous population of receptors with α5 subunit coexpression than there was without it. In addition, the responses of cells coexpressing α5 subunits with α3 and β2 subunits were generally very low, suggesting that α5 subunit expression may have limited the formation of functional receptors or α5-containing receptors have different activation properties, resulting in a low probability of being open.

The coexpression of α5 subunits with mouse α3β2 and α3β4 subunits also affected inhibition by decamethonium and hexamethonium. For α3β2-containing receptors, α5 subunit coexpression reduced the potency of decamethonium, whereas for α3β4-containing receptors α5 subunit coexpression increased the potency of both decamethonium and hexamethonium (Tables 4 and 5). In contrast, the coexpression of mouse α5 with mouse α4 and β2 subunits did not alter the IC50 values (Tables 4 and 5) for inhibition by decamethonium and hexamethonium relative to cells expressing only α4 and β2 subunits (data not shown), suggesting that the α5 subunit was not being efficiently incorporated into α4β2-containing receptors.

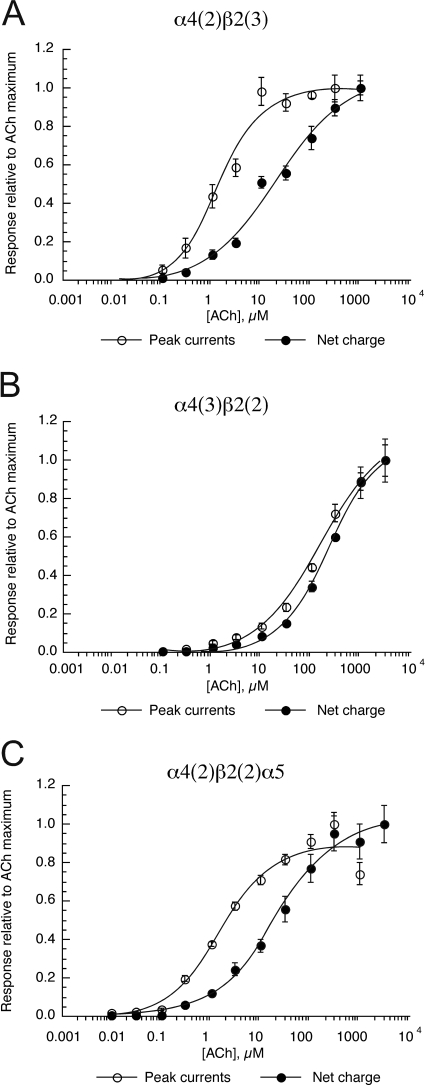

Effects of Coexpression of the Human β2–6-α4 Concatamer with Human α4, β2, or α5 Subunits.

Because the coexpression of α5 subunits had little effect on mouse receptors expressing α4 and β2 subunits, to further test the potential importance of α5 subunit coexpression on the inhibitory activity of hexamethonium and decamethonium experiments were conducted with linked human α4 and β2 subunits to generate receptors with fixed subunit composition (Zhou et al., 2003). As reported, coexpression of the β2–6-α4 construct with either monomeric β2, α4, or α5 subunits generates three distinct homogeneous receptor populations (Tapia et al., 2007). The CRCs for ACh peak currents and net charge for these receptors are shown in Fig. 11. Note that the HS α4(2)β2(3) (Fig. 11A) and α4(2)β2(2)α5 (Fig. 11C) receptors show a shift in the apparent potency of ACh for the net charge measure compared with the peak currents. The reason for this is that, although the peak currents of these receptors reach a maximal amplitude at relatively low ACh concentration, the HS receptors continue to respond as the agonist concentration decreases in the chamber, generating broad responses with progressively larger amounts of net charge (not shown). In contrast, the LS α4(3)β2(2) receptors (Fig. 11B) require a higher ACh concentration to activate, and the responses decay rapidly as soon as the ACh concentration begins to decrease (not shown).

Fig. 11.

ACh responses of human nAChR formed with concatamers. Shown are the peak current and net charge data for human α4β2 receptors with fixed subunit composition, formed by the coexpression of the linked β2 and α4 subunits (β2–6-α4 construct; Zhou et al., 2003) with monomeric β2 (A), α4 (B), or α5 (C). Data are expressed relative to the ACh maximal responses. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

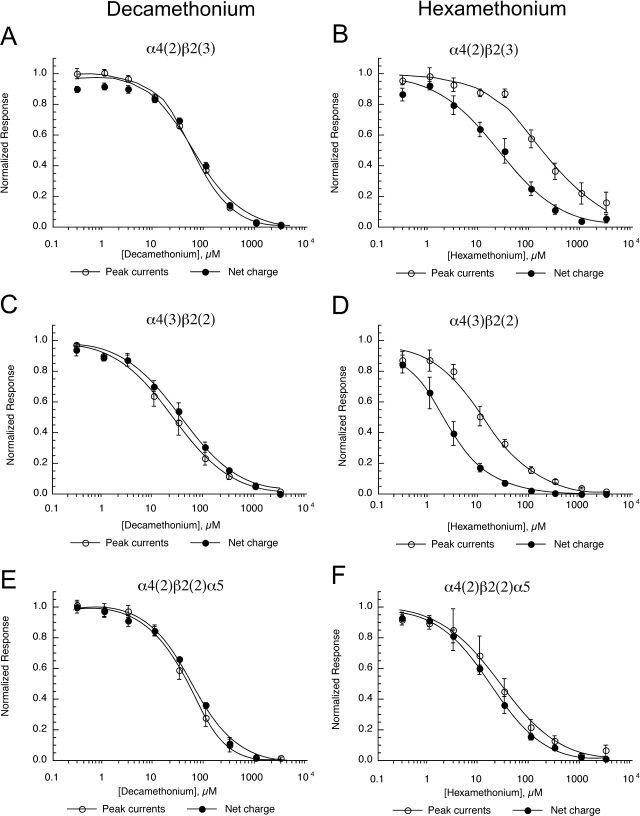

Coexpression of the β2–6-α4 construct with monomeric β2, α4, or α5 subunits did not alter the effects of decamethonium on the receptors (Fig. 12). However, the relative inhibition of net charge and peak current by hexamethonium was influenced by the expression of α5 subunits in place of either α4 or β2 subunits. The α5-containing receptors showed a decrease in the separation of the two inhibition curves to a point where there were no differences in the inhibition of net charge and peak currents, in contrast to the receptor subtypes containing only α4 and β2 subunits. A summary of the effects of the concatamers on ACh responses and inhibition by decamethonium and hexamethonium is presented in Table 7.

Fig. 12.

Decamethonium and hexamethonium inhibition of human nAChR formed with concatamers. Shown are the peak current and net charge data for human α4β2 receptors with fixed subunit composition, formed by the coexpression of the linked β2 and α4 subunits (β2–6-α4 construct; Zhou et al., 2003) with monomeric β2 (A and B), α4 (C and D), or α5 (E and F) obtained in the presence of increasing concentrations of decamethonium (A, C, and E) or hexamethonium (B, D, and F). Data are expressed relative to the control responses to applications of ACh alone. Each point is the average ± S.E.M. of responses from at least four oocytes.

TABLE 7.

Activation and inhibition of human α4β2* receptors with fixed subunit composition

| Receptor | Peak Current | Net Charge | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| μM | |||

| Activation: EC50 values for ACh (Fig. 10) | |||

| α4(2)β2(3) (HS) | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 22 ± 9 | 14.6 |

| α4(3)β2(2) (LS) | 155 ± 23 | 261 ± 28 | 1.68 |

| α4β2α5 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 20.5 ± 3.5 | 13.3 |

| Antagonism of human α4β2 nAChR subtypes by decamethonium: IC50 values (Fig. 12) | |||

| α4(2)β2(3) (HS) | 56 ± 3 | 60 ± 8 | 1.07 |

| α4(3)β2(2) (LS) | 23 ± 1.5 | 33 ± 3 | 1.4 |

| α4β2α5 | 43 ± 1.3 | 53 ± 3.5 | 1.23 |

| Antagonism of human α4β2 nAChR subtypes by hexamethonium: IC50 values (Fig. 12) | |||

| α4(2)β2(3) (HS) | 178 ± 25 | 23 ± 3 | 0.13 |

| α4(3)β2(2) (LS) | 11.9 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.16 |

| α4β2α5 | 23.5 ± 2.3 | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 0.66 |

Discussion

These studies provide an important reference for comparing mouse nAChR with published studies that have used receptors cloned from other species (Hussy et al., 1994; Zwart et al., 2006; Papke et al., 2008). The ACh responses of mouse nAChR are generally similar to those of human and rat receptors. The complex CRCs obtained with the pairwise expression of mouse neuronal α and β subunits support the hypothesis that the oocyte expression system allows the assembly of receptors with varying subunit composition and agonist sensitivity. In these studies this complexity was further revealed by the comparison of measures of peak current and net charge. These observations are also consistent with the complex concentration-response relationships obtained with native receptors from mouse brain (Grady et al., 2009). The ACh concentration-response studies for mouse α7 receptors are also consistent with what has been reported for α7 receptors of several other species (Papke, 2006).

Because the mouse is frequently used as a model for depression (Mineur et al., 2009; Rollema et al., 2009) and nicotine dependence (Picciotto et al., 1998), it is important that these studies have confirmed the extent to which the pharmacology of cytisine and its derivatives varenicline and 3-pyr-Cyt are similar to what has been reported for the receptors from other species (Table 2). However, it is also important to note the difference in the reversibility of the effects of varenicline on mouse receptors compared with rat and human α4β2 receptors. Varenicline is potent in mouse models of antidepressant activity (Rollema et al., 2009), and, at least in part, this may be a reflection of the slow reversibility of its effects, which could lead to relatively large equilibrium desensitization of α4β2 receptors in the mouse. However, it should also be noted that there are two functionally distinguishable genetic variants of the mouse α4 subunit that differ by a single amino acid at residue 529 (Dobelis et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2003). The most common α4 variant in mice contains a threonine at this position, whereas the less common variant has an alanine. The experiments reported here used the common variant of α4 because it is the form of α4 found in C57BL/6 mice, the mouse strain most frequently used in research. Whether varenicline would have the same effect on α4β2 nAChRs possessing the other variant of α4 remains to be determined. Regardless, the varenicline data would, at the very least, caution against straightforward translation of data from mice possessing the threonine variant of α4 to human therapeutics.

The results obtained with 3-pyr-Cyt, a compound shown to be efficacious in the mouse forced-swim model of depression (Mineur et al., 2009), are consistent with the hypothesis that the efficacy of this compound involves inhibition rather than activation of α4β2 receptors. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation that the nonselective nAChR antagonist mecamylamine is also effective in the forced-swim model.

Decamethonium continues to be used clinically as a muscle relaxant and experimentally as a pharmacological tool (Ball and Westhorpe, 2005). Consistent with previous reports (Liu and Dilger, 1993), we confirmed that decamethonium was a partial agonist for muscle receptors and had no agonist activity on any of the neuronal receptor subtypes tested. Our experiments therefore confirm the traditional classification of decamethonium as a selective depolarizing blocker of muscle-type nAChR (Paton and Zaimis, 1949). With single-channel measurements of Popen, which are effectively equivalent to measurement of net charge, Liu and Dilger (1993) estimated the efficacy of 100 μM decamethonium to be only 2% that of ACh. We also estimated the efficacy of 100 μM decamethonium to be approximately 2% the ACh maximum. Although decamethonium was a selective partial agonist on muscle-type receptors, it was nonetheless an effective antagonist of mouse neuronal nAChR, and particularly potent for inhibition of homomeric α7 receptors, compared with other subtypes (Table 4).

Hexamethonium continues to be used as an experimental tool for distinguishing between the CNS and peripheral effects of nicotine and other cholinergic drugs (Andreasen et al., 2008) by comparing and contrasting its effects with those of mecamylamine. Because hexamethonium does not cross the blood-brain barrier, but mecamylamine does, hexamethonium blocks only the peripheral effects of nicotinic drugs.

Although hexamethonium is typically classified as a “ganglionic blocker ” (Paton and Perry, 1953), our data indicate that it showed no great selectivity for mouse α3-containing receptors that serve as models for ganglionic receptors. The inhibitory potency of hexamethonium for muscle-type receptors and α4β2-type receptors, which serve as models for high-affinity receptors in the brain, was essentially comparable with its potency for inhibiting α3-containing receptors. This would suggest that perhaps the traditional classification of hexamethonium as a ganglionic blocker might have been caused by the functional protection of muscle and brain receptors in early whole-animal studies. The function of α4β2 receptors in the brain would have been maintained by the exclusion of hexamethonium at the blood-brain barrier, whereas muscle function would have been protected by the large receptor reserve of the neuromuscular junction.

Although the inhibition of muscle-type receptors by decamethonium is clearly through a competitive mechanism, hexamethonium decreased the maximum responses of muscle receptors without change in the apparent EC50, suggesting a strictly noncompetitive mechanism. However, although the competition studies suggested noncompetitive inhibition of muscle-type receptors by hexamethonium, the inhibition was not voltage-dependent, which suggests that the site of binding of hexamethonium to muscle receptors was not within the electric field of the membrane.

Differential effects on peak current amplitude and net charge measures provide insight into the mechanism of action and kinetics of inhibition (Neher and Steinbach, 1978; Jonsson et al., 2006). The preferential inhibition of net charge compared with peak current is often indicative of use-dependent inhibition (Neher and Steinbach, 1978). This trend was only strongly apparent for the inhibition of β2-containing receptors by hexamethonium (Figs. 5 and 6). In general, the data suggest that inhibition of all the neuronal receptors by either agent may have been caused by both competitive and noncompetitive activities.

The coexpression of α5 subunits with α3-containing receptors had functional effects, perhaps decreasing the receptor heterogeneity that was apparent when α3 and β4 subunits were expressed alone. Recent data with knockout mice have suggested that the majority of functional receptors in autonomic ganglia have α3β4 subunit composition, sometimes coassembled with α5 (Wang et al., 2005). Our data show that the α3β4α5 receptors had greater sensitivity to hexamethonium than did the other potential ganglionic models, α3β4, α3β2, and α3β2α5 (Table 5). Interestingly, it has been reported that α5 knockout mice are more sensitive than wild type to cardiac blockade by hexamethonium (Wang et al., 2002), suggesting that the knockout might have decreased the receptor reserve in the cardiac ganglia, indirectly increasing sensitivity to hexamethonium.

The use of linked subunits can provide improved control over the subunit composition of receptors formed in the oocyte expression system (Zhou et al., 2003; Kuryatov et al., 2008). Because we have shown that the inhibitory activity of the novel antagonist 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-yl heptanoate was strongly regulated by the presence or absence of the α5 subunit (Papke et al., 2005), we used human β2–6-α4 concatamers to achieve a controlled condition for the presence or absence of α5 subunits. The inhibitory activity of decamethonium was unaffected by α4, β2, or α5 in the position of the structural subunit. The potency for decamethonium inhibition of these human α4β2-containing receptors was also not significantly different from its potency for inhibiting the mouse α4β2 receptors (compare Tables 4 and 7).

The primary effect of the inclusion of the α5 subunit in human α4β2-containing receptors on inhibition by hexamethonium was to reduce the IC50 values for peak current and net charge. This effect might have been caused by a change in the relative contributions of competitive and noncompetitive inhibitory activity.

The ultimate power of transgenic mouse models for human disease and therapeutics will have to rely on the translation of scientific results on multiple levels, in particular, at the molecular level. In this study we have demonstrated that mouse nicotinic receptor clones are an important model for human nAChR function, and we have identified the molecular properties of the three primary classes of receptors. This is one necessary step on the path that will bridge mouse disease models to the human conditions we desire to treat. As demonstrated by the difference in varenicline reversibility between human and mouse α4β2 receptors, it may be dangerous to assume that any single expression system will be sufficient for predictive in vitro pharmacology. Comparisons between species are important at both the level of the intact organisms and the level of the single identified effector molecules.

Acknowledgments

We thank Clare Stokes, Lynda Cortés, Shehd Abdullah Abbas Al Rubaiy, and Sara Braley for technical assistance; Marina Picciotto and Sigismund Huck for helpful comments; and Daniela Gündisch for the supply of 3-pyr-Cyt.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants GM57481, DA014369].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.109.164566.

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- ACh

- acetylcholine

- CRC

- concentration-response curve

- HS

- high sensitivity

- LS

- low sensitivity

- 3-pyr-Cyt

- 3-(pyridin-3′-yl)-cytisine

- DHβE

- dihydro-β-erythroidine

- CNS

- central nervous system

- MS222

- 3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester.

References

- Andreasen JT, Olsen GM, Wiborg O, Redrobe JP. (2008) Antidepressant-like effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists, but not agonists, in the mouse forced swim and mouse tail suspension tests. J Psychopharmacol 23:797–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, Dowell C, Watkins M, Stitzel JA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. (2005) α-Conotoxin BuIA, a novel peptide from Conus bullatus, distinguishes among neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem 280:80–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball C, Westhorpe R. (2005) Muscle relaxants: decamethonium. Anaesth Intensive Care 33:709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Changeux JP. (2004) Knockout and knockin mice to investigate the role of nicotinic receptors in the central nervous system. Prog Brain Res 145:235–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, Sands SB, Davis TI, Lebel LA, Fox CB, et al. (2005) Varenicline: an α4β2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem 48:3474–3477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge WJ, Ulloa L. (2007) The α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor as a pharmacological target for inflammation. Br J Pharmacol 151:915–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobelis P, Marks MJ, Whiteaker P, Balogh SA, Collins AC, Stitzel JA. (2002) A polymorphism in the mouse neuronal α4 nicotinic receptor subunit results in an alteration in receptor function. Mol Pharmacol 62:334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady SR, Salminen O, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Collins AC. (2009) Mouse striatal dopamine nerve terminals express α4α5β2 and two stoichiometric forms of α4β*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Mol Neurosci 40:91–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussy N, Ballivet M, Bertrand D. (1994) Agonist and antagonist effects of nicotine on chick neuronal nicotinic receptors are defined by α and β subunits. J Neurophys 72:1317–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson M, Gurley D, Dabrowski M, Larsson O, Johnson EC, Eriksson LI. (2006) Distinct pharmacologic properties of neuromuscular blocking agents on human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a possible explanation for the train-of-four fade. Anesthesiology 105:521–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Flanagin BA, Qin C, Macdonald RL, Stitzel JA. (2003) The mouse Chrna4 A529T polymorphism alters the ratio of high- to low-affinity α4β2 nAChRs. Neuropharmacology 45:345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Onksen J, Lindstrom J. (2008) Roles of accessory subunits in α4β2* nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 74:132–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dilger JP. (1993) Decamethonium is a partial agonist at the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Synapse 13:57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marubio LM, Changeux J. (2000) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor knockout mice as animal models for studying receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol 393:113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. (2006) Varenicline is a partial agonist at α4β2 and a full agonist at α7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol 70:801–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar NS, Gotti C. (2009) Diversity of vertebrate nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 56:237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Eibl C, Young G, Kochevar C, Papke RL, Gundisch D, Picciotto MR. (2009) Cytisine-based nicotinic partial agonists as novel antidepressant compounds. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, Cassels BK, Bermudez I. (2006) α4β2 Nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol 70:755–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Steinbach JH. (1978) Local anaesthetics transiently block current through single acetylcholine receptor channels. J Physiol 277:135–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. (2003) Alternate stoichiometries of α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 63:332–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL. (2006) Estimation of both the potency and efficacy of α7 nAChR agonists from single-concentration responses. Life Sci 78:2812–2819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL. (2009) Tricks of perspective: insights and limitations to the study of macroscopic currents for the analysis of nAChR activation and desensitization. Mol Neurosci 40:77–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Buhr JD, Francis MM, Choi KI, Thinschmidt JS, Horenstein NA. (2005) The effects of subunit composition on the inhibition of nicotinic receptors by the amphipathic blocker 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-yl heptanoate. Mol Pharmacol 67:1977–1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA, Zheng G, Zhang Z, McIntosh JM, Stokes C. (2008) Extending the analysis of nicotinic receptor antagonists with the study of α6 nicotinic receptor subunit chimeras. Neuropharmacology 54:1189–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Heinemann SF. (1994) The partial agonist properties of cytisine on neuronal nicotinic receptors containing the β2 subunit. Mol Pharm 45:142–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Papke JKP. (2002) Comparative pharmacology of rat and human α7 nAChR conducted with net charge analysis. Br J Pharmacol 137:49–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton WDA, Perry WLM. (1953) The relationship between depolarization and block in the cat's superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol 119:43–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton WDA, Zaimis EJ. (1949) The pharmacological actions of polymethylene bis-trimethylammonium salts. Br J Pharmacol 4:381–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick J, Boulter J, Goldman D, Gardner P, Heinemann S. (1987) Molecular biology of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Ann NY Acad Sci 505:194–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto M, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio L, Pich E, Fuxe K, Changeux J. (1998) Acetylcholine receptors containing the β2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature 391:173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Mather RJ, Rovetti CC, et al. (2007) Pharmacological profile of the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology 52:985–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Guanowsky V, Mineur YS, Shrikhande A, Coe JW, Seymour PA, Picciotto MR. (2009) Varenicline has antidepressant-like activity in the forced-swim test and augments sertraline's effect. Eur J Pharmacol 605:114–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JA, Dobelis P, Jimenez M, Collins AC. (2001) Long sleep and short sleep mice differ in nicotine-stimulated 86Rb+ efflux and α4 nicotinic receptor subunit cDNA sequence. Pharmacogenetics 11:331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel JA, Farnham DA, Collins AC. (1996) Linkage of strain-specific nicotinic receptor α7 subunit restriction fragment-length polymorphisms with levels of α-bungarotoxin binding in brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 43:30–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia L, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. (2007) Ca2+ permeability of the (α4)3(β2)2 stoichiometry greatly exceeds that of (α4)2(β2)3 human acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol 71:769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Orr-Urtreger A, Chapman J, Ergun Y, Rabinowitz R, Korczyn AD. (2005) Hidden function of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor β2 subunits in ganglionic transmission: comparison to α5 and β4 subunits. J Neurol Sci 228:167–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Orr-Urtreger A, Chapman J, Rabinowitz R, Nachman R, Korczyn AD. (2002) Autonomic function in mice lacking α5 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Physiol 542:347–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CR, Role LW. (1998) Functional contribution of the α5 subunit to neuronal nicotinic channels expressed by chick sympathetic ganglion neurones. J Physiol 509:667–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi C, Cooper J, Lindstrom J. (2003) Human α4β2 acetylcholine receptors formed from linked subunits. J Neurosci 23:9004–9015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Broad LM, Xi Q, Lee M, Moroni M, Bermudez I, Sher E. (2006) 5-I A-85380 and TC-2559 differentially activate heterologously expressed α4β2 nicotinic receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 539:10–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]