Abstract

Substitution of arginine-137 of the vasopressin type 2 receptor (V2R) for histidine (R137H-V2R) leads to nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), whereas substitution of the same residue to cysteine or leucine (R137C/L-V2R) causes the nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (NSIAD). These two diseases have opposite clinical outcomes. Still, the three mutant receptors were shown to share constitutive β-arrestin recruitment and endocytosis, resistance to vasopressin-stimulated cAMP production and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation, and compromised cell surface targeting, raising questions about the contribution of these phenomenons to the diseases and their potential treatments. Blocking endocytosis exacerbated the elevated basal cAMP levels promoted by R137C/L-V2R but not the cAMP production elicited by R137H-V2R, demonstrating that substitution of Arg137 to Cys/Leu, but not His, leads to constitutive V2R-stimulated cAMP accumulation that most likely underlies NSIAD. The constitutively elevated endocytosis of R137C/L-V2R attenuates the signaling and most likely reduces the severity of NSIAD, whereas the elevated endocytosis of R137H-V2R probably contributes to NDI. The constitutive signaling of R137C/L-V2R was not inhibited by treatment with the V2R inverse agonist satavaptan (SR121463). In contrast, owing to its pharmacological chaperone property, SR121463 increased the R137C/L-V2R maturation and cell surface targeting, leading to a further increase in basal cAMP production, thus disqualifying it as a potential treatment for patients with R137C/L-V2R-induced NSIAD. However, vasopressin was found to promote β-arrestin/AP-2-dependent internalization of R137H/C/L-V2R beyond their already elevated endocytosis levels, raising the possibility that vasopressin could have a therapeutic value for patients with R137C/L-V2R-induced NSIAD by reducing steady-state surface receptor levels, thus lowering basal cAMP production.

The arginine vasopressin (AVP) system plays a crucial role in water homeostasis. AVP is synthesized in the hypothalamus and is released upon increased plasma osmolality, decreased arterial pressure, and heart volume reduction (Treschan and Peters, 2006; Ball, 2007). In the distal collecting tubules of the kidney, AVP promotes water reabsorption through the aquaporin 2 water channel (AQP2) by binding to and activating the vasopressin type 2 receptor (V2R). This receptor, which belongs to the family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), promotes cAMP production through the activation of Gαs and adenylyl cyclase. It has been suggested that the resulting phosphorylation of AQP2 by protein kinase A promotes its insertion into the apical plasma membrane of the renal collecting duct principal cells, leading to increased water permeability (Treschan and Peters, 2006; Ball, 2007). Renal insensitivity to AVP results in a failure to reabsorb water, leading to excessive water excretion (>30 ml/kg body weight per day for adults) and diluted urine (<250 mmol/kg), causing dehydration and pathological hypernatremia, a disease known as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) (Fujiwara and Bichet, 2005). Most NDI cases result from mutations in the V2R gene (AVPR2). To date, more than 200 NDI-causing mutations in AVPR2 have been associated with loss of function of V2R signaling (Fujiwara and Bichet, 2005; Spanakis et al., 2008). One of these missense mutations, leading to substitution of an arginine to a histidine at position 137 (R137H), was shown to cause loss of function of the V2R as a result of a dramatic decrease in cell surface expression induced by both constitutive internalization and intracellular retention of the receptor caused by its impaired maturation (Barak et al., 2001; Bernier et al., 2004b). Unexpectedly, Feldman et al. (2005) reported that substitution of the same arginine residue by either cysteine or leucine (R137C or R137L) caused a distinct renal disorder associated with a V2R gain of function, leading to excessive water reabsorption, hyponatremia, and seizures. This newly described syndrome was termed nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (NSIAD) (Feldman et al., 2005). Characterization of the R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R signaling properties revealed constitutively elevated basal V2R-promoted cAMP production (Feldman et al., 2005). Although the structural mechanisms involved in GPCR activation are still incompletely understood, the well conserved DR137Y/H motif is thought to be involved in the intramolecular interactions that stabilize inactive and/or activated conformations of various GPCRs (Rovati et al., 2007).

Although previous studies have extensively investigated the loss-of-function R137H-V2R (Barak et al., 2001; Bernier et al., 2004b), only limited data are available for R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. Kocan et al. (2009) have reported that, as previously shown for R137H-V2R (Bernier et al., 2004b), R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R promote agonist-independent recruitment of β-arrestin to the receptor and the subsequent internalization of the receptor/β-arrestin complex. Despite this increased constitutive β-arrestin recruitment, which should blunt the Gαs signaling activity, significantly elevated cAMP production was observed. This contrasts with the absence of spontaneous Gαs activation for the R137H substitution and most likely contributes to the opposite pathological outcomes resulting from these different substitutions at position 137. To determine whether other functional properties, specific to R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R, contribute to the gain of function associated with these V2R mutants, we characterized multiple functional properties of these mutant receptors by investigating their maturation and cell surface targeting, basal and agonist-stimulated cAMP production, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation, and constitutive and ligand-regulated endocytosis. Finally, we investigated the potential therapeutic benefit of using a V2R-specific inverse agonist [satavaptan (SR121463)] on the gain of function of the R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R mutant receptors and thus its suitability as a potential therapeutic agent for NSIAD.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum, G-418 (Geneticin), l-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin were purchased from Wisent (St-Bruno, QC, Canada). Fugene6 was obtained from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN). Coelenterazine-h was from Prolume (Pinetop, AZ). Poly-d-lysine, 8-arginine-vasopressin (AVP), and the antibodies against the FLAG epitope (M1 and M2) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Canada (Mississauga, ON, Canada). Antibodies recognizing the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and their phosphorylated forms (P-ERKs) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA), and anti-mouse and anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG were from GE Healthcare (Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). The enhanced chemiluminescence lightning substrate was obtained from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA). The white opaque and clear-bottomed 96-well plates were from Corning Life Sciences (Lowell, MA). The Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody was from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, PA). The Mithras LB940 from Berthold Technologies (Bad Wildbad, Germany) was the plate reader used to measure the first generation of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET1), and the ARTEMIS TR-FRET microplate reader (Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to read the homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) technology assays in this study.

Plasmid Constructs and Mutagenesis.

A FLAG epitope-tagged human V2R has been described previously (Klein et al., 2001). FLAG-R137L-V2R, FLAG-R137C-V2R, and FLAG-R137H-V2R mutant constructs were generated from the FLAG-WT-V2R by using site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions to replace Arg137 by the appropriate amino acid. The same strategy was used to generate the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein-tagged (EYFP) mutant V2R by using the previously published EYFP-WT V2R (Charest and Bouvier, 2003). The Renilla reniformis luciferase (Rluc)-tagged β-arrestin2 (β-arrestin2-Rluc), the EYFP-tagged β2-adaptin (β2-adaptin-EYFP) (Hamdan et al., 2007), and the dominant-negative mutant of dynamin (DynK44A) (Rochdi and Parent, 2003) constructs have been described previously.

Cell Culture and Plasmid Transfections.

Unless otherwise stated, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM glutamine at 37°C in a humidified chamber at 95% air and 5% CO2. For transfections in six-well plates, 4 × 105 HEK293 cells were seeded and transfected the next day by using Fugene6 according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Measurement of Cell Surface Expression and AVP-Induced Internalization.

Agonist-promoted internalization was assessed as described previously (Rochdi and Parent, 2003) by using HEK293 cells transiently expressing the different V2R constructs. In brief, the culture medium was removed and replaced with DMEM/0.5% bovine serum albumin/20 mM HEPES in the presence or absence of AVP. After 60-min incubation at 37°C, the medium was removed and cells were fixed with Tris-buffered saline/3.7% formaldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. Cell surface expression was measured by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and anti-FLAG M2 monoclonal antibody. The percentage of agonist-promoted receptor internalization was determined as follows: (1 − stimulated/unstimulated) × 100.

Total Cell Extract Analysis by Western Blot.

Proteins from total cell lysates were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) before being transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Protein immunodetection on membranes was done by using the anti-FLAG M2 (0.2 μg/ml) antibody.

BRET1 Measurement of β-Arrestin2/β2-Adaptin Interaction.

A stable β2-adaptin-EYFP cell line generated as described previously (Hamdan et al., 2007) was transfected with β-arrestin2-Rluc and either the WT-V2R, R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, or R137L-V2R constructs. Approximately 18 h after transfection, cells were detached by trypsinization and seeded (approximately 5 × 104 cells/well) into opaque 96-well (white walls, clear bottoms) tissue culture plates previously treated with poly-d-lysine, and reincubated at 37°C for another 18 h. On the day of the experiment, the culture medium was replaced by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with or without agonist at room temperature for the specified time. To measure the BRET1 signal, the clear bottom of the 96-well white plate was covered with a white-backed tape adhesive (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences), and the BRET1 substrate for Rluc, coelenterazine-h, was added to all wells (5 μM final concentration), followed by BRET1 measurement on the Mithras LB940 plate reader, which allows the sequential integration of signals detected in the 480 ± 20- and 530 ± 20-nm windows. The BRET1 signal was calculated as a ratio of the light emitted by EYFP (530 ± 20 nm) over the light emitted by Rluc (480 ± 20 nm). Total luciferase and EYFP values were comparable in each condition tested.

BRET1 Measurement of β-Arrestin Recruitment to WT and Mutant V2R.

EYFP-tagged WT and mutant V2R were transiently coexpressed with the β-arrestin2-Rluc in HEK293 cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were detached in PBS and distributed in an opaque 96-well plate. Cells were then stimulated for 20 min at 37°C with increasing amounts of AVP (from 10−15 to 10−5 M) before the addition of coelenterazine-h (5 μM final) and BRET measurement using the Mithras LB940 plate reader. Potency values (EC50) of the AVP-promoted β-arrestin recruitment to the receptors were determined by using Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

Visualization of Receptor Localization and Internalization by Fluorescence Microscopy.

FLAG-tagged mutant receptors present at the plasma membrane were specifically labeled with the M1 monoclonal antibody, and subsequent internalization was visualized by using a minor modification of a method described previously (Gage et al., 2001). In brief, HEK293 cells stably or transiently expressing the indicated FLAG-tagged receptor constructs were plated on glass coverslips (Corning Life Sciences), and surface receptors were specifically labeled by incubating intact cells with the M1 anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (2.5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 30 min in the absence of agonist. The cells were then incubated (37°C for 30 min) in the presence or absence of 10 μM AVP (Sigma-Aldrich), as indicated. Cells were then fixed for 10 min by using 3.7% formaldehyde freshly dissolved in PBS followed by three washes using Tris-buffered saline supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2. Fixed specimens were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in Blotto (3% dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 1 mM CaCl2) and incubated with Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:500 dilution) for 45 min. Fluorescence microscopy was performed with an inverted Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Diaphot microscope equipped with a Nikon 60× numerical aperture 1.4 objective and epifluorescence optics. Images were collected with a 12-bit cooled charge-coupled device camera (Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) interfaced to a Macintosh computer (Apple Computer, Cupertino, CA).

cAMP Accumulation Measurement.

cAMP accumulation was measured by using the cAMP dynamic 2 kit (Cisbio, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. In brief, HEK293 cells transiently expressing either WT-V2R, R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, or R137L-V2R were transferred into a 384-well plate (5 × 104 cells/well). AVP or vehicle was then added to the cell suspension followed by 15-min incubation at room temperature. Thereafter, conjugate+lysis buffer and d2cAMP were added to each well followed by the addition of the anti-cAMP cryptate antibody. The plate was then incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and HTRF was measured. Results were obtained by calculating the 665/620-nm values ratio expressed in ΔF.

Reporter Gene Assay of cAMP Signaling.

HEK293 cells were transfected with the WT-V2R or mutant constructs along with the cAMP-responsive luciferase reporter plasmid [CRE-luciferase, containing 16 copies of the consensus cAMP response element (Vaisse et al., 2000)] and the R. reniformis luciferase reporter plasmid [pRL-CMV (Promega, Madison, WI) to control for transfection efficiency]. When stable cell lines were used (WT-V2R or R137L-V2R), cells were transfected only with the CRE-luciferase reporter plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity by using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) as described previously (Stables et al., 1999; Flück et al., 2002). Data are expressed as the mean luciferase activity, in arbitrary units, and normalized to WT-V2R-promoted luciferase activity.

cRNA Synthesis, Oocyte Preparation, Injection, and Electrophysiological Recording.

cDNA-containing plasmids were linearized with the Pvu1 restriction enzyme and used as templates for capped cRNA synthesis using mMESSAGE MACHINE kits (Ambion, Austin, TX). Xenopus laevis oocytes were prepared as described previously (Kovoor et al., 1997), and cRNA was injected (50 nl/oocyte) with a Drummond Scientific (Broomall, PA) microinjector. Oocytes were incubated for 48 h after injection in normal oocyte saline buffer solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) and supplemented with sodium pyruvate (2.5 mM) and gentamicin (50 μg/ml) before their transfer to recording buffer (74 mM NaCl, 24 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) to enhance sensitivity for inward K+ conductance. For electrophysiological analysis, oocytes were clamped at −80 mV with two electrodes filled with 3 M KCl having resistances of 0.5 to 1.5 MΩ, by using a GeneClamp 500 amplifier and pCLAMP 9 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). All data were digitally recorded (Digidata; Molecular Devices) and low-pass filtered.

ERK1/2 Phosphorylation Assay.

Cells transiently expressing the different V2R constructs were grown in six-well plates and rendered quiescent by serum starvation for 16 h before a 5-min stimulation with 1 μM AVP. Plates were then put on ice, and the cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and solubilized directly in 150 μl of Laemmli sample buffer containing 50 mM dithiothreitol. The samples were sonicated for 15 s and heated for 5 min at 95°C before SDS-PAGE. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was detected by immunoblotting and chemiluminescence using mouse monoclonal anti-P-ERK and anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies. After densitometric quantification of phosphorylation, membranes were stripped of immunoglobulins and reprobed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-ERK antibody. ERK phosphorylation was normalized according to the protein loads by expressing the data as a ratio of P-ERK over total ERK. Immunoreactivities were determined by densitometric analysis of the films using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Statistical analysis and curve fitting were done with Prism software. Statistical significance of the differences was assessed by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Bonferroni's test.

Results

Cell Surface Expression of R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R Mutants.

It has previously been shown that several mutations within the coding sequence of V2R affect the level of receptor cell surface expression (Bichet et al., 1994; Wenkert et al., 1996; Ranadive et al., 2009). In particular, R137H-V2R has been reported to have low steady-state surface expression, owing in part to its constitutive internalization once it reaches the cell surface (Barak et al., 2001; Bernier et al., 2004b; Hamdan et al., 2007). To determine whether substitutions of arginine 137 to either leucine or cysteine residues also affect receptor cell surface density, ELISA was carried out on intact HEK293 cells transiently expressing R137C-V2R, R137L-V2R, R137H-V2R, and WT-V2R bearing a FLAG epitope at the N terminus to allow immunodetection. Figure 1A shows that, compared with WT-V2R, R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R exhibit an approximately 40% reduction in cell surface expression, which is equivalent to what is observed for R137H-V2R. The reduced cell surface expression of one of the mutant receptors (R137L-V2R) was further confirmed by radioligand binding experiments using [3H]AVP as the tracer (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Saturable high-affinity binding was observed with both transiently expressing WT-V2R and R137L-V2R cells, but significantly lower maximal binding was systematically observed in cells expressing the mutant receptor. Moreover, affinity toward AVP was similar for all V2R constructs, as determined by radio-ligand binding saturation experiments (see Supplementary Table 1).

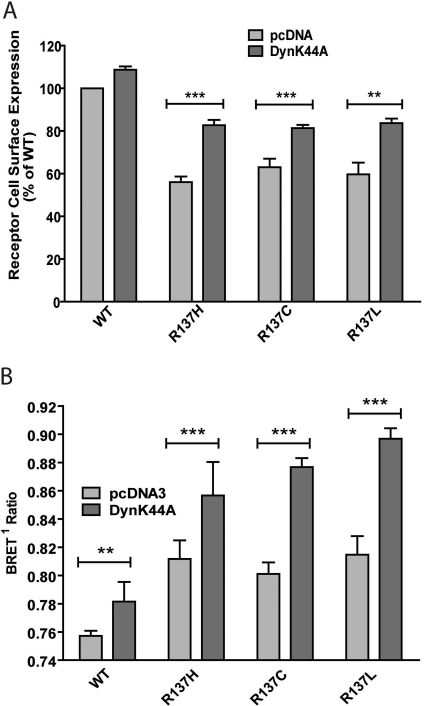

Fig. 1.

Cell surface expression of WT-V2R, R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R and their constitutive internalization. A, HEK293 cells, transiently expressing the indicated V2R constructs along with the overexpression of DynK44A or an empty vector (pcDNA3), were assessed for receptor surface expression by ELISA using an anti-FLAG antibody as described under Materials and Methods. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing the β2-adaptin-EYFP subunit of the AP-2 complex were transfected with the indicated V2R constructs and β-arrestin2-Rluc, with or without DynK44A overexpression. β-Arrestin2 and AP-2 interaction was monitored by BRET. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three to five independent experiments. Statistical significance of the difference was assessed by paired Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01.

To determine whether, as shown for R137H-V2R, the reduced cell surface expression of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R results from constitutive internalization, we quantitatively assessed the effect of a dynamin dominant negative mutant, DynK44A, that has been shown to inhibit both constitutive and agonist-induced internalization by preventing the pinching off of the endocytic vesicles without preventing the assembly of the internalization machinery (Damke et al., 1994; Hamdan et al., 2007). As shown in Fig. 1A, cotransfecting DynK44A modestly increased the cell surface expression of the WT receptor (by less than 10%), whereas surface expression of R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R increased by 48, 29, and 40%, respectively, indicating that constitutive endocytosis is involved in the reduced steady-state cell surface expression of the three mutants.

To explore further the mechanism underlying the constitutive endocytosis, we took advantage of the recently developed BRET-based assay, monitoring the interaction between β-arrestin2 and the β2 subunit of the clathrin adaptor AP-2 (β2-adaptin) (Hamdan et al., 2007). The basal BRET between β2-adaptin-EYFP and β-arrestin2-luciferase was significantly higher in cells transiently expressing R137C-V2R, R137L-V2R, or R137H-V2R compared with cells expressing WT-V2R (Fig. 1B), indicating that the mutant receptors constitutively promote the assembly of the β-arrestin2/AP-2 complex, resulting into spontaneous endocytosis. In all cases, inhibition of this spontaneous endocytosis with DynK44A led to a significant increase of the BRET signal, reflecting the accumulation of the receptor/β-arrestin/AP-2 complex in the unsevered endocytotic vesicles (Fig. 1B).

Agonist-Promoted Internalization of R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R.

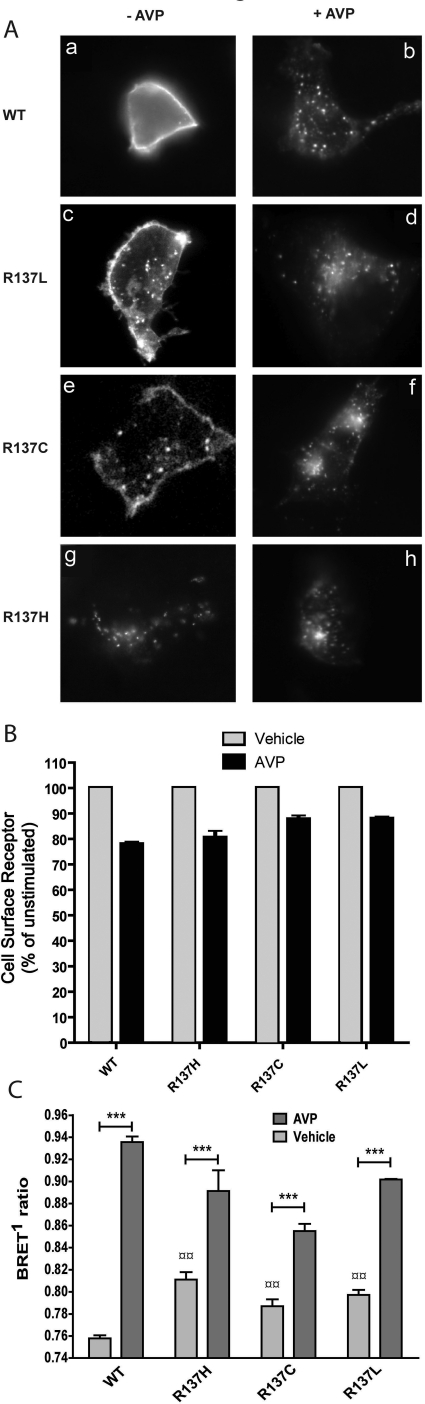

To investigate whether, in addition to their constitutive internalization, R137C-V2R, R137L-V2R, and R137H-V2R could still undergo agonist-promoted internalization, immunofluorescence microscopy, cell surface ELISA, and β-arrestin2/AP-2 BRET experiments were performed on transiently expressing cells, in the presence or absence of AVP stimulation. As shown in Fig. 2A, WT-V2R is located almost exclusively at the cell surface in the absence of AVP stimulation, whereas R137C-V2R, R137L-V2R, and R137H-V2R are seen in intracellular vesicles, confirming their constitutive endocytosis. AVP treatment (10 μM) led to a massive redistribution of WT-V2R from the plasma membrane into endocytic vesicles and promoted additional endocytosis of the mutant receptors. The ability of the mutant receptors to undergo agonist-promoted endocytosis despite their already high level of spontaneous endocytosis was further confirmed and quantified by cell-surface ELISA (Fig. 2B). Likewise, although the β-arrestin2/AP-2 BRET signal was already elevated for the three mutant receptors, 1 μM AVP further increased the BRET signal (Fig. 2C), indicating that hormone binding promotes additional engagement of the endocytic machinery. Such agonist-promoted engagement of the endocytic machinery by the mutant receptors was further confirmed by performing dose-response curves of β-arrestin2 recruitment directly to the receptors by BRET using transiently expressed EYFP-tagged versions of WT-V2R, R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R, in combination with the Rluc-tagged β-arrestin construct (Table 1). The results show that the EC50 values are similar for all receptors, confirming that the mutations do not affect the affinity for AVP or the ability of the AVP-bound receptors to recruit β-arrestin2.

Fig. 2.

Agonist-induced internalization of wild-type and mutant V2R assessed by fluorescence microscopy, cell surface ELISA, and BRET. A, HEK293 cells transiently expressing the FLAG-tagged WT-V2R (a and b), R137L-V2R (c and d), R137C-V2R (e and f), or R137H-V2R (g and h) were surface-labeled with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody as described under Materials and Methods and incubated in the absence (a, c, e, and g) or presence (b, d, f, and h) of 10 μM AVP for 30 min before fixation. Representative epifluorescence images are shown. B, HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs, and receptor internalization was determined by measuring cell surface receptor expression after the incubation of the transfected cells in the absence or presence of AVP (1 μM) using the cell surface ELISA and anti-FLAG antibody. C, HEK293 cells stably expressing the EYFP-fused β2-adaptin subunit of the AP-2 complex were transfected with the indicated V2R constructs and β-arrestin2-Rluc. BRET1 measurements of the β-arrestin2/AP-2 biosensor were done after 20-min incubation with or without AVP (1 μM). Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three to five independent experiments. Statistical significance of the difference was assessed by paired Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001. One-way ANOVA combined with Tukey's multiple comparison test was also performed. ¤¤, p < 0.01.

TABLE 1.

AVP-induced β-arrestin2 recruitment potencies

EC50 was determined as described under Materials and Methods. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three independent experiments.

| Receptor Expressed | Log EC50 |

|---|---|

| M | |

| WT-V2R | −9.44 ± 0.09 |

| R137H-V2R | −9.53 ± 0.12 |

| R137C-V2R | −9.34 ± 0.19 |

| R137L-V2R | −9.64 ± 0.17 |

Signaling Properties of the R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R Mutants.

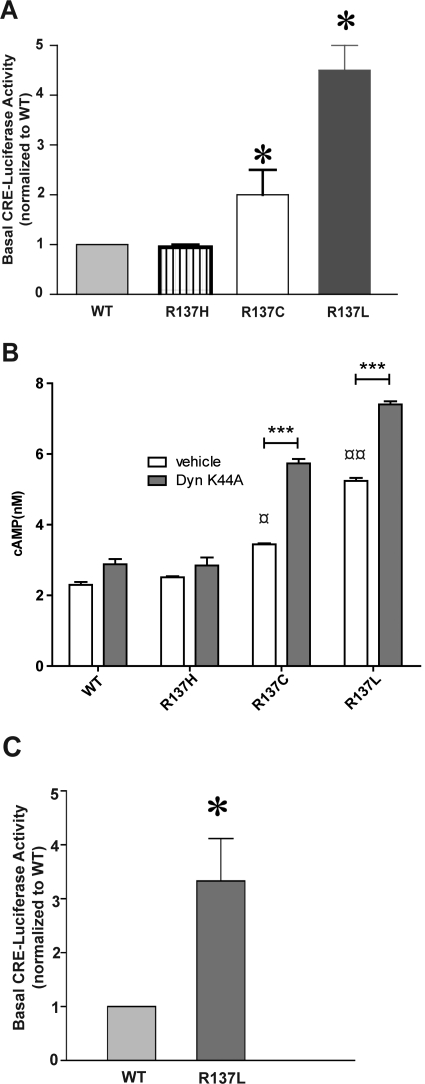

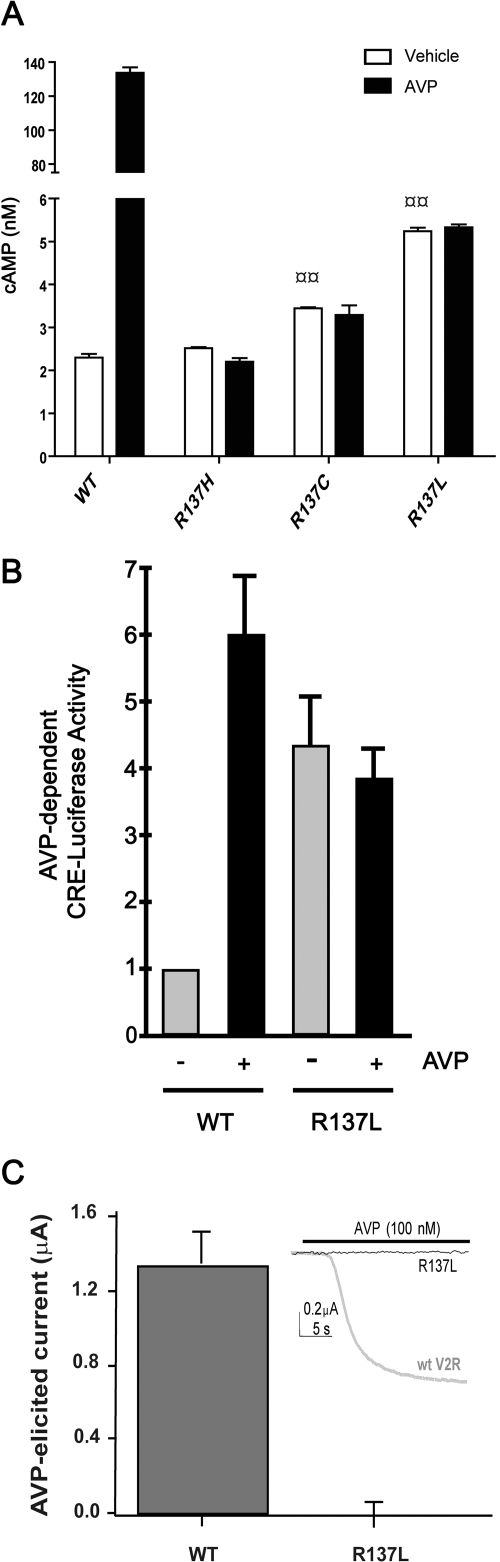

It has been shown previously that the R137H substitution causes a loss of AVP-induced cAMP production (Barak et al., 2001; Bernier et al., 2004b). For R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R, which were shown to promote elevated basal cAMP production, no information is available about the AVP-stimulated response. Basal and AVP-stimulated cAMP production was therefore investigated in cells transiently expressing WT-V2R, R137H-V2R, R137L-V2R, or R137C-V2R. Whether measured using the CRE-luciferase reporter gene assay (Fig. 3A) or a FRET-based cAMP immune-detection assay (Fig. 3B), an elevated basal cAMP production was observed for both R137L-V2R or R137C-V2R compared with WT-V2R, confirming their increased constitutive activity toward the cAMP production pathway. The higher basal cAMP production promoted by R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R was further exacerbated when preventing their internalization with DynK44A (Fig. 3B), suggesting that the manifestation of their constitutive activity is dampened by their concomitant endocytosis. The elevated basal cAMP levels observed did not result from different expression levels because clonal populations of cells stably expressing similar number of WT-V2R and R137L-V2R (Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 1) confirmed that R137L-V2R promotes significantly higher cAMP production than its WT counterpart (Fig. 3C). It should be noted that, as was observed in transiently expressing cells, the affinity for [3H]AVP was the same for the WT and mutant forms of the receptor (Supplementary Table 1). Despite the elevated basal activity observed in cells transiently expressing R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R, no further increase in cAMP production could be detected after 1 μM AVP stimulation (Fig. 4A), a loss of responsiveness that was also observed for R137H-V2R. These results were further confirmed by using the highly sensitive CRE-luciferase reporter gene assay in cells stably expressing the same level of WT-V2R and R137L-V2R (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Although R137L-V2R's basal activity was higher than that of WT-V2R, no increase in luciferase activity could be observed after a 24-h stimulation with 1 μM AVP in cells expressing R137L-V2R, whereas a 6-fold increase was observed in cells expressing the WT receptor (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Constitutive cAMP signaling of the mutant V2Rs. A, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated V2R and the CRE-luciferase reporter constructs, and lysates were assayed for luciferase 24 h later. In each experiment, reporter gene activity was measured in three replicate wells, and the average value from cells expressing R137L-V2R, R137C-V2R, or R137H-V2R mutant was normalized to the average value from cells expressing WT-V2R. The bars indicate the mean of normalized luciferase activity across three independent experiments. B, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated receptors and either the DynK44A construct or a control plasmid (pcDNA3). cAMP production was measured by using a HTRF-based technology as described under Materials and Methods. C, stably transfected HEK293 cell clones expressing FLAG-tagged WT-V2R or R137L-V2R, which were matched for receptor expression (see Supplementary Fig. 2), were transfected with the CRE-luciferase reporter construct, and lysates were assayed for luciferase activity 24 h later. In each experiment, reporter gene activity was measured in three replicate wells, and the average value from cells expressing R137L-V2R mutant was normalized to the average value from cells expressing WT-V2R. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three to five independent experiments. Statistical significance of the difference was assessed by using paired Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05. One-way ANOVA combined with Tukey's multiple comparison test was also performed. ¤¤, p < 0.01; ¤, p < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

AVP-dependent signaling and G protein coupling estimated by cAMP production measurement and potassium channel currents in oocytes. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with WT or mutant V2R constructs, as indicated. Agonist-induced cAMP production was assessed after 15-min incubation in the presence or absence of AVP (1 μM) using a HTRF-based method as described under Materials and Methods. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing the indicated V2R were transfected with the CRE-luciferase reporter construct, incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM AVP for 24 h, and lysed for luciferase activity measurements. In each experiment, triplicate wells were assayed for each condition and the luminescence units measured from AVP-exposed cells were normalized to the WT-V2R expressing cells not exposed to AVP. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. from three independent experiments. C, oocytes were injected with 4 ng of cRNA of either WT-V2R or the R137L-V2R mutant along with 1 ng each of Gαs, GIRK1, and GIRK4 cRNA. Current amplitude produced by the application of AVP was then measured. The inset shows a representative trace of AVP evoked current in an oocyte injected with either WT-V2R cRNA (thick gray trace) or mutant R137L-V2R cRNA (thin black trace). The horizontal bar above the traces indicates AVP application. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three to five independent experiments. Statistical significance of the difference was assessed by using one-way ANOVA combined with Tukey's multiple comparison test. ¤¤, p < 0.01.

The loss of AVP-promoted Gαs pathway activation by V2R was further confirmed for the R137L mutant by monitoring G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channel (GIRK) activation in frog oocytes coexpressing Gαs and the subunits GIRK1 and GIRK4 (Lim et al., 1995; Kovoor et al., 1997). As shown in Fig. 4C, 1 μM AVP stimulation induced a robust inward current in oocytes expressing WT-V2R, whereas no response was detected in R137L-V2R-expressing oocytes.

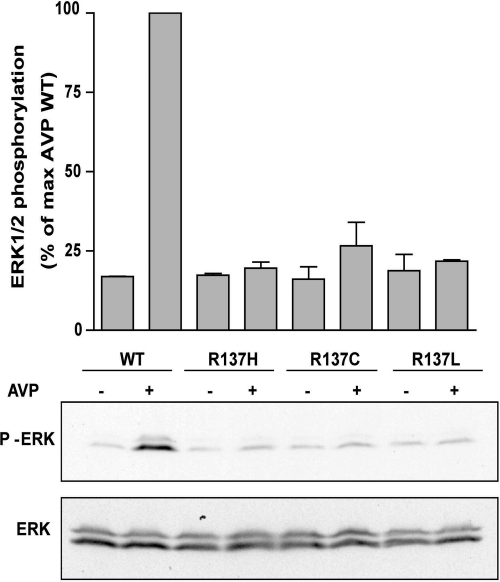

AVP binding to V2R has been shown to promote activation of ERK1/2 (Péqueux et al., 2004). To assess whether substitution of Arg137 for Cys, Leu, or His could also affect this signaling pathway, AVP-promoted ERK1/2 phosphorylation was measured in transiently expressing V2R cells. As expected, WT-V2R induced a robust ERK1/2 phosphorylation upon 1 μM AVP stimulation, whereas no AVP-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was observed in cells expressing R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, or R137L-V2R (Fig. 5), indicating that the loss of AVP responsiveness is not limited to the cAMP production pathway.

Fig. 5.

V2R-promoted MAPK activation. AVP-induced MAPK activation was assessed in HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated V2R constructs. After 5-min incubation in the presence (+) or absence (−) of AVP (1 μM), cells were lysed in Laemmli sample buffer and extracts were resolved by SDS-PAGE. MAPK activity was detected by Western blot using a phosphospecific anti-ERK1/2 antibody (P-ERK1/2). Expression level of ERK1/2 was controlled by using an antibody directed against the total kinase population (ERK1/2). Data are expressed as the percentage of P-ERK/ERK of the level observed for AVP-stimulated WT-V2R conditions. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. of at least three independent experiments. The Western blots shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Although elevated constitutive endocytosis and loss of both AVP-stimulated cAMP production and ERK1/2 activation are shared by R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R, the increased basal cAMP production promoted by R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R was not observed for R137H-V2R, whether constitutive endocytosis was blocked or not (Fig. 3, A and B), revealing at least one intrinsic difference (constitutive activity toward the cAMP pathway) between the Arg137 substitutions causing NDI versus NSIAD.

Maturation and Pharmacological Chaperoning of R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R.

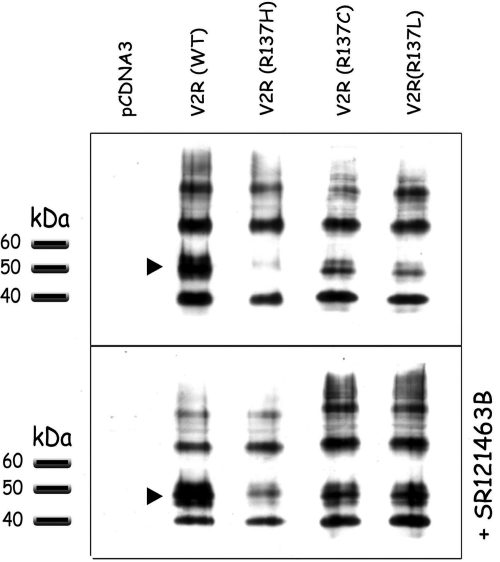

The R137H-V2R mutant has previously been shown to have impaired folding, leading to a decrease expression of the mature form of the receptor as monitored by its glycosylation state (Morello and Bichet, 2001). Such impaired maturation was partially corrected by sustained treatment with selective lipophilic ligands acting as pharmacological chaperones (Morello et al., 2000; Bernier et al., 2004a,b). To determine whether these properties are shared by R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R, we assessed their maturation profiles in transiently expressing cells, in the absence and presence of the pharmacological chaperone SR121463. Our results show that, like the NDI-associated R137H-V2R, the NSIAD-causing R137C and R137L substitutions affect receptor maturation, as indicated by a reduction of the fully glycosylated form (approximately 50 kDa) of the three mutant receptors compared with the WT (Fig. 6). As observed for R137H-V2R, the SR121463 treatment (10 μM) favored maturation of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R, as revealed by the marked increase of the fully glycosylated form of the receptor.

Fig. 6.

Effects of the R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R substitutions on receptor maturation profile. HEK293 cells transfected with the indicated receptors were incubated in the absence (top) or presence (bottom) of SR121463 (10 μM) for 16 h. Cells extracts were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and receptors were visualized by Western blotting using an anti-FLAG antibody. Arrowheads indicate the fully glycosylated mature form of V2R. Data shown are representative of three to four experiments.

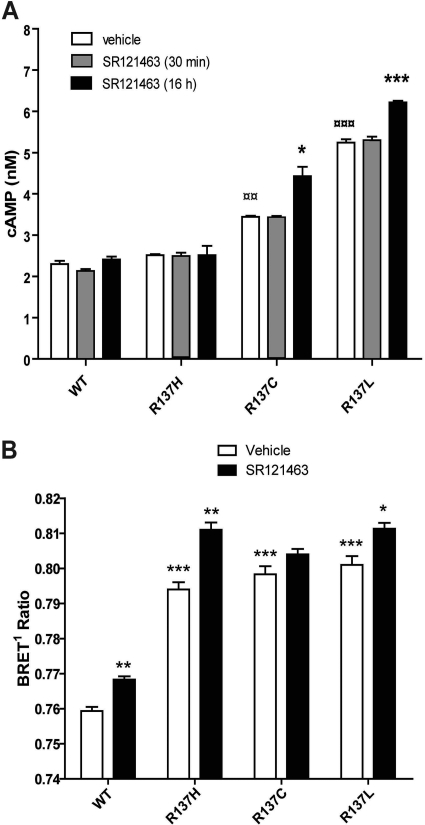

Effect of V2R-Specific Inverse Agonist on the Constitutive Signaling of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R Mutants.

It has previously been shown that, in addition to its pharmacological chaperone property, the V2R antagonist SR121463 is endowed with inverse agonist activity toward the artificially designed constitutively active mutant D136A-V2R (Morin et al., 1998). We therefore assessed the ability of this compound to silence the constitutive activity of transiently expressed R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. Figure 7A shows that a short-term (30 min) treatment with 10 μM SR121463 did not affect the elevated basal cAMP production promoted by R137C and R137L, indicating that SR121463 does not act as an inverse agonist on these mutants. Longer-term (16 h) treatment with SR121463 also did not reveal any inverse agonist effects. In fact, it potentiated the elevated basal cAMP accumulation observed in cells expressing R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. This potentiating effect is most likely caused by the increased number of constitutively active receptor at the cell surface, because of the pharmacological chaperone property of SR121463 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7.

Effect of V2R inverse agonist SR121463 on the constitutive cAMP production and constitutive endocytosis promoted by R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated constructs. Forty-eight hours later, cells were incubated for another 16 h in the absence or presence of SR121463 (10 μM), and basal cAMP production was measured by using a HTRF-based technology as described under Materials and Methods. B, HEK293 cells stably expressing β2-adaptin-EYFP were transfected with the β-arrestin2-Rluc and the indicated receptor constructs. Cells were subsequently incubated for 16 h in the presence or absence of SR121463 (10 μM), and BRET1 was measured as described under Materials and Methods.

Because R137H-V2R, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R were all found to promote constitutive association of β-arrestin2 with AP-2, leading to the internalization of the receptor (Fig. 2B), we assessed whether it could be blocked by SR121463. As shown in Fig. 7B, the elevated BRET between β-arrestin2-Rluc and β2-adaptin-EYFP promoted by the transient expression of the three mutant receptors was not reduced upon SR121463 treatment. In fact, the treatment tended to increase the BRET signal promoted by the receptors, most likely, again, as a result of the SR121463-promoted elevation of cell surface receptor number.

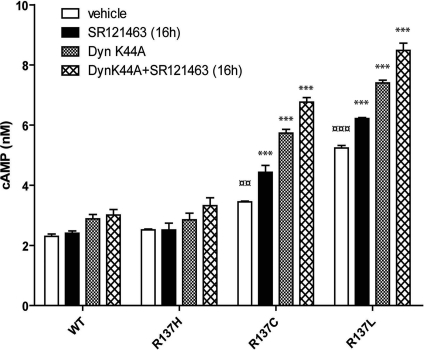

Combined Effects of Misfolding and Constitutive Internalization on the Constitutive Activity of the R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R Mutants.

Our results show that both constitutive internalization and partial intracellular retention of NSIAD-causing R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R contribute to lower cell surface receptor levels. Together, these two phenomena should therefore reduce the extent of constitutive activity detected in cells expressing the NSIAD-causing mutant receptors. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the effect of inhibiting receptor endocytosis (using DynK44A cotransfection) in combination with increasing receptor targeting to the cell surface (using 10 μM SR121463) on basal cAMP production. As shown in Fig. 8, the combined overexpression of DynK44A and long-term SR121463 treatment resulted in an additive increase in cAMP accumulation in HEK293 cells expressing R137C-V2R or R137L-V2R but not in cells expressing either R137H-V2R or WT-V2R.

Fig. 8.

Combined effects of misfolding and constitutive internalization on the constitutive activity of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated V2R construct and either DynK44A or a control plasmid. Cells were then incubated in the presence or absence of SR121463 (10 μM) for 16 h, and basal cAMP production was measured by using HTRF-based technology. Data shown are the mean ± S.E.M. of three to five independent experiments. Statistical significance of the difference was assessed by using paired Student's t test. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01. One-way ANOVA combined with the Tukey's multiple comparison test was also performed. ¤¤¤, p < 0.001; ¤¤, p < 0.01.

Discussion

Our characterization of the molecular defects of the NSIAD-causing mutants R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R has revealed a high degree of similarity with the previously described NDI-causing mutant R137H-V2R. First, the three mutant receptors were shown to undergo elevated constitutive endocytosis, as revealed by a considerably reduced steady-state cell surface level that could be partly normalized by inhibiting constitutive internalization. These results are consistent with a recent study reporting that the three receptors were constitutively localized in intracellular vesicles (Kocan et al., 2009). For the three mutant receptors, our results show that the elevated endocytosis arises from the same mechanism involving the constitutive engagement of the clathrin-dependent pathway, as revealed by the increased basal BRET observed between β-arrestin2 and β2-adaptin. These results are in agreement with previous reports demonstrating that R137H-V2R, as well as R137L-V2R and R137C-V2R, spontaneously recruit β-arrestin2 in the absence of agonist stimulation (Bernier et al., 2004b; Kocan et al., 2009). Despite their constitutive internalization, the three mutant receptors can still recruit β-arrestin and engage the β-arrestin2/AP-2 complex upon AVP stimulation, leading to additional internalization. These results indicate that the substitutions only partially mimic or stabilize the receptor conformation recruiting the endocytic machinery.

The three mutant receptors also shared altered maturation, as revealed by a decreased proportion of the fully glycosylated form of the receptors, indicative of reduced Golgi processing. This altered processing is also revealed by the ability of pharmacological chaperones to promote receptor maturation and cell surface targeting. These results contrast with the recent suggestion, based on qualitative immunofluorescence analyses, that R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R forward trafficking is not impaired and that their constitutive endocytosis is solely responsible for the decreased cell surface expression (Kocan et al., 2009). Kocan et al. (2009) concluded that this represents a major difference between R137H-V2R on one hand and between R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R on the other. In contrast, our results show that both impaired maturation and elevated constitutive endocytosis contribute to the reduced steady-state cell surface expression of R137C-V2R, R137L-V2R, and R137H-V2R. Consistent with this notion, inhibition of endocytosis only partially restored cell surface expression of the three mutant receptors.

An additional characteristic shared by the three mutants is their inability to promote both cAMP production and ERK1/2 activation upon AVP stimulation, indicating a common loss of functional responsiveness. One cannot exclude that the mutant receptors could allow a weak agonist-promoted Gαs signaling that fell below the detection threshold. However, this is unlikely because no AVP-stimulated cAMP production could be observed for R137L-V2R, even when the highly amplified CRE-luciferase reporter assay was used. The loss of responsiveness does not originate from a loss of AVP binding to the receptor, because AVP affinity, as determined by radio-ligand binding studies, was similar for all receptors studied and, as indicated above, AVP-induced recruitment of the endocytic machinery and subsequent endocytosis were observed for all mutant receptors. The fact that AVP is able to promote internalization but is unable to stimulate detectable cAMP production or ERK1/2 activation suggests that the active conformation required for β-arrestin2 and downstream endocytic effectors recruitment is different from those leading to Gαs and ERK1/2 activation.

The only difference observed between the loss-of-function R137H-V2R mutant and the gain-of-function mutants R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R resides in their basal constitutive activity toward the cAMP pathway. Indeed, whereas R137H-V2R basal activity is indistinguishable from that of the WT receptor, R137C-V2R, and R137L-V2R promoted higher basal cAMP levels in accordance with what we previously reported (Feldman et al., 2005).

Of interest, the elevated basal activity of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R was observed despite the constitutive recruitment of β-arrestin2, which is known to abrogate receptor-promoted Gαs signaling (Barki-Harrington and Rockman, 2008). This raises the intriguing possibility that the balance between the constitutive engagement of Gαs and β-arrestin2 may determine the extent of basal cAMP production and explain the difference between the NSIAD and NDI-causing mutations described herein.

Inverse agonists have recently emerged as a group of bioactive compounds that can bind to constitutively active receptors and reduce their basal signaling (Rodríguez-Puertas and Barreda-Gómez, 2006) and thus could represent a potential therapeutic avenue. The inverse agonist SR121463, which was shown to reduce the constitutive cAMP production promoted by the artificially designed D136A-V2R, however, was unable to silence the constitutive activity of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R. In fact, the effect of the compound increased basal cAMP level promoted by the receptors, most likely as a consequence of the increased receptor number reaching the cell surface because of its pharmacological chaperone action. The lack of inverse agonist effect of SR121463 on R137C-V2R- and R137L-V2R-promoted cAMP production is consistent with the absence of therapeutic activity in hyponatremic patients with NSIAD carrying the R137C substitution in their V2R (Decaux et al., 2007). At the mechanistic level, the inability of SR121463 to silence the constitutive activity of R137C-V2R and R137L-V2R suggests that the structural changes causing the constitutive activation of the mutant receptors cannot be reversed by the inverse agonist binding. Although less likely, the resistance of the spontaneous activity to the inhibitory action of SR121463 could indicate that the elevated cAMP production could result from the increased expression or activation of another Gαs or adenylyl cyclase-activating protein as a result of the expression of the mutant V2R.

Although found inactive for treating patients with NSIAD harboring the R137C and R137L substitutions, the pharmacological chaperone properties of SR121463 made it an effective treatment for patients with NDI carrying R137H-V2R (Bernier et al., 2006). In contrast, the ideal compound to treat NSIAD would have inverse agonist efficacy toward the cAMP pathway but lack pharmacological chaperone activity. Thus screening for such ligands, using R137C-V2R- and R137L-V2R-expressing cells, would be a rational approach for the discovery of a NSIAD treatment. Reducing cell surface expression of the receptor by either inhibiting receptor targeting to the cell surface or promoting its endocytosis could also represent alternative therapeutic avenues because reduced steady-state surface receptor levels would result in lower basal cAMP production. AVP administration could represent such a therapeutic avenue for these patients, because we found that AVP promoted a reduction in cell surface receptor without activating the cAMP or the ERK1/2 pathways.

In conclusion, our study shows that, although they lead to some common receptor anomalies, distinct substitutions occurring at a same position also have distinct consequences that are responsible for the opposite clinical outcomes observed for R137H versus R137L/C. This illustrates the importance of a detailed characterization of the functional consequences of receptor mutants for understanding the molecular basis of the disease and providing clues for the development of therapeutic avenues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Monique Lagacé for valuable insights and thorough reading of the manuscript.

] The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants DA010711, DA012864]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health [Grant 1K08-MH68691-01]; the Kidney Foundation of Canada; and studentships, fellowships, and awards from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Fond de la Recherche en Santé du Québec, and the Canada Research Chair in Signal Transduction and Molecular Pharmacology.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.109.061804.

- V2R

- vasopressin type 2 receptor

- AVP

- arginine vasopressin

- AP-2

- adaptin 2

- AQP2

- aquaporin 2 water channel

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- NDI

- nephrogenic diabetes insipidus

- NSIAD

- nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- P-ERK

- phosphorylated ERK

- BRET1

- first generation of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- HTRF

- homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence technology

- Rluc

- Renilla reniformis luciferase

- EYFP

- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- DynK44A

- dominant negative mutant of dynamin

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- PAGE

- polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- WT

- wild type

- GIRK

- G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium channel

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- SR121463

- satavaptan

- CRE

- cAMP response element.

References

- Ball SG. (2007) Vasopressin and disorders of water balance: the physiology and pathophysiology of vasopressin. Ann Clin Biochem 44:417–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak LS, Oakley RH, Laporte SA, Caron MG. (2001) Constitutive arrestin-mediated desensitization of a human vasopressin receptor mutant associated with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:93–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barki-Harrington L, Rockman HA. (2008) β-Arrestins: multifunctional cellular mediators. Physiology (Bethesda) 23:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier V, Bichet DG, Bouvier M. (2004a) Pharmacological chaperone action on G-protein-coupled receptors. Curr Opin Pharmacol 4:528–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier V, Lagacé M, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Bichet DG, Bouvier M. (2004b) Functional rescue of the constitutively internalized V2 vasopressin receptor mutant R137H by the pharmacological chaperone action of SR49059. Mol Endocrinol 18:2074–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier V, Morello JP, Zarruk A, Debrand N, Salahpour A, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Laperrière A, Brouard R, Bouvier M, et al. (2006) Pharmacologic chaperones as a potential treatment for X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol 17:232–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet DG, Birnbaumer M, Lonergan M, Arthus MF, Rosenthal W, Goodyer P, Nivet H, Benoit S, Giampietro P, Simonetti S. (1994) Nature and recurrence of AVPR2 mutations in X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Am J Hum Genet 55:278–286 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest PG, Bouvier M. (2003) Palmitoylation of the V2 vasopressin receptor carboxyl tail enhances β-arrestin recruitment leading to efficient receptor endocytosis and ERK1/2 activation. J Biol Chem 278:41541–41551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damke H, Baba T, Warnock DE, Schmid SL. (1994) Induction of mutant dynamin specifically blocks endocytic coated vesicle formation. J Cell Biol 127:915–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaux G, Vandergheynst F, Bouko Y, Parma J, Vassart G, Vilain C. (2007) Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis in adults: high phenotypic variability in men and women from a large pedigree. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BJ, Rosenthal SM, Vargas GA, Fenwick RG, Huang EA, Matsuda-Abedini M, Lustig RH, Mathias RS, Portale AA, Miller WL, et al. (2005) Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med 352:1884–1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flück CE, Martens JW, Conte FA, Miller WL. (2002) Clinical, genetic, and functional characterization of adrenocorticotropin receptor mutations using a novel receptor assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:4318–4323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara TM, Bichet DG. (2005) Molecular biology of hereditary diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:2836–2846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage RM, Kim KA, Cao TT, von Zastrow M. (2001) A transplantable sorting signal that is sufficient to mediate rapid recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 276:44712–44720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan FF, Rochdi MD, Breton B, Fessart D, Michaud DE, Charest PG, Laporte SA, Bouvier M. (2007) Unraveling G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis pathways using real-time monitoring of agonist-promoted interaction between β-arrestins and AP-2. J Biol Chem 282:29089–29100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein U, Müller C, Chu P, Birnbaumer M, von Zastrow M. (2001) Heterologous inhibition of G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis mediated by receptor-specific trafficking of β-arrestins. J Biol Chem 276:17442–17447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocan M, See HB, Sampaio NG, Eidne KA, Feldman BJ, Pfleger KD. (2009) Agonist-independent interactions between β-arrestins and mutant vasopressin type II receptors associated with nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Mol Endocrinol 23:559–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Nappey V, Kieffer BL, Chavkin C. (1997) μ and δ Opioid receptors are differentially desensitized by the coexpression of β-adrenergic receptor kinase 2 and β-arrestin 2 in Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 272:27605–27611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim NF, Dascal N, Labarca C, Davidson N, Lester HA. (1995) A G protein-gated K channel is activated via β2-adrenergic receptors and Gβγ subunits in Xenopus oocytes. J Gen Physiol 105:421–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello JP, Bichet DG. (2001) Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Annu Rev Physiol 63:607–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello JP, Salahpour A, Laperrière A, Bernier V, Arthus MF, Lonergan M, Petäjä-Repo U, Angers S, Morin D, Bichet DG, et al. (2000) Pharmacological chaperones rescue cell-surface expression and function of misfolded V2 vasopressin receptor mutants. J Clin Invest 105:887–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin D, Cotte N, Balestre MN, Mouillac B, Manning M, Breton C, Barberis C. (1998) The D136A mutation of the V2 vasopressin receptor induces a constitutive activity which permits discrimination between antagonists with partial agonist and inverse agonist activities. FEBS Lett 441:470–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Péqueux C, Keegan BP, Hagelstein MT, Geenen V, Legros JJ, North WG. (2004) Oxytocin- and vasopressin-induced growth of human small-cell lung cancer is mediated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocr Relat Cancer 11:871–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranadive SA, Ersoy B, Favre H, Cheung CC, Rosenthal SM, Miller WL, Vaisse C. (2009) Identification, characterization, and rescue of a novel vasopressin-2 receptor mutation causing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Clin Endocrinol 71:388–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochdi MD, Parent JL. (2003) Gαq-coupled receptor internalization specifically induced by Gαq signaling. Regulation by EBP50. J Biol Chem 278:17827–17837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Puertas R, Barreda-Gómez G. (2006) Development of new drugs that act through membrane receptors and involve an action of inverse agonism. Recent Patents CNS Drug Discov 1:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovati GE, Capra V, Neubig RR. (2007) The highly conserved DRY motif of class A G protein-coupled receptors: beyond the ground state. Mol Pharmacol 71:959–964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanakis E, Milord E, Gragnoli C. (2008) AVPR2 variants and mutations in nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: review and missense mutation significance. J Cell Physiol 217:605–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stables J, Scott S, Brown S, Roelant C, Burns D, Lee MG, Rees S. (1999) Development of a dual glow-signal firefly and Renilla luciferase assay reagent for the analysis of G protein-coupled receptor signalling. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 19:395–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treschan TA, Peters J. (2006) The vasopressin system: physiology and clinical strategies. Anesthesiology 105:599–612; quiz 639–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaisse C, Clement K, Durand E, Hercberg S, Guy-Grand B, Froguel P. (2000) Melanocortin-4 receptor mutations are a frequent and heterogeneous cause of morbid obesity. J Clin Invest 106:253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenkert D, Schoneberg T, Merendino JJ, Jr, Rodriguez Pena MS, Vinitsky R, Goldsmith PK, Wess J, Spiegel AM. (1996) Functional characterization of five V2 vasopressin receptor gene mutations. Mol Cell Endocrinol 124:43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.