Abstract

Plastics are inexpensive, lightweight and durable materials, which can readily be moulded into a variety of products that find use in a wide range of applications. As a consequence, the production of plastics has increased markedly over the last 60 years. However, current levels of their usage and disposal generate several environmental problems. Around 4 per cent of world oil and gas production, a non-renewable resource, is used as feedstock for plastics and a further 3–4% is expended to provide energy for their manufacture. A major portion of plastic produced each year is used to make disposable items of packaging or other short-lived products that are discarded within a year of manufacture. These two observations alone indicate that our current use of plastics is not sustainable. In addition, because of the durability of the polymers involved, substantial quantities of discarded end-of-life plastics are accumulating as debris in landfills and in natural habitats worldwide.

Recycling is one of the most important actions currently available to reduce these impacts and represents one of the most dynamic areas in the plastics industry today. Recycling provides opportunities to reduce oil usage, carbon dioxide emissions and the quantities of waste requiring disposal. Here, we briefly set recycling into context against other waste-reduction strategies, namely reduction in material use through downgauging or product reuse, the use of alternative biodegradable materials and energy recovery as fuel.

While plastics have been recycled since the 1970s, the quantities that are recycled vary geographically, according to plastic type and application. Recycling of packaging materials has seen rapid expansion over the last decades in a number of countries. Advances in technologies and systems for the collection, sorting and reprocessing of recyclable plastics are creating new opportunities for recycling, and with the combined actions of the public, industry and governments it may be possible to divert the majority of plastic waste from landfills to recycling over the next decades.

Keywords: plastics recycling, plastic packaging, environmental impacts, waste management, chemical recycling, energy recovery

1. Introduction

The plastics industry has developed considerably since the invention of various routes for the production of polymers from petrochemical sources. Plastics have substantial benefits in terms of their low weight, durability and lower cost relative to many other material types (Andrady & Neal 2009; Thompson et al. 2009a). Worldwide polymer production was estimated to be 260 million metric tonnes per annum in the year 2007 for all polymers including thermoplastics, thermoset plastics, adhesives and coatings, but not synthetic fibres (PlasticsEurope 2008b). This indicates a historical growth rate of about 9 per cent p.a. Thermoplastic resins constitute around two-thirds of this production and their usage is growing at about 5 per cent p.a. globally (Andrady 2003).

Today, plastics are almost completely derived from petrochemicals produced from fossil oil and gas. Around 4 per cent of annual petroleum production is converted directly into plastics from petrochemical feedstock (British Plastics Federation 2008). As the manufacture of plastics also requires energy, its production is responsible for the consumption of a similar additional quantity of fossil fuels. However, it can also be argued that use of lightweight plastics can reduce usage of fossil fuels, for example in transport applications when plastics replace heavier conventional materials such as steel (Andrady & Neal 2009; Thompson et al. 2009b).

Approximately 50 per cent of plastics are used for single-use disposable applications, such as packaging, agricultural films and disposable consumer items, between 20 and 25% for long-term infrastructure such as pipes, cable coatings and structural materials, and the remainder for durable consumer applications with intermediate lifespan, such as in electronic goods, furniture, vehicles, etc. Post-consumer plastic waste generation across the European Union (EU) was 24.6 million tonnes in 2007 (PlasticsEurope 2008b). Table 1 presents a breakdown of plastics consumption in the UK during the year 2000, and contributions to waste generation (Waste Watch 2003). This confirms that packaging is the main source of waste plastics, but it is clear that other sources such as waste electronic and electrical equipment (WEEE) and end-of-life vehicles (ELV) are becoming significant sources of waste plastics.

Table 1.

Consumption of plastics and waste generation by sector in the UK in 2000 (Waste Watch 2003).

| usage |

waste arising |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ktonne | (%) | ktonne | (%) | |

| packaging | 1640 | 37 | 1640 | 58 |

| commercial andindustrial | 490 | |||

| household | 1150 | |||

| building and construction | 1050 | 24 | 284 | 10 |

| structural | 800 | 49 | ||

| non-structural | 250 | 235 | ||

| electrical and electronics | 355 | 8 | 200 | 7 |

| furniture and housewares | 335 | 8 | 200a | 7 |

| automotive and transport | 335 | 8 | 150 | 5 |

| agriculture and horticulture | 310 | 7 | 93 | 3 |

| other | 425 | 10 | 255a | 9 |

| total | 4450 | 2820 | ||

aestimate

Because plastics have only been mass-produced for around 60 years, their longevity in the environment is not known with certainty. Most types of plastics are not biodegradable (Andrady 1994), and are in fact extremely durable, and therefore the majority of polymers manufactured today will persist for at least decades, and probably for centuries if not millennia. Even degradable plastics may persist for a considerable time depending on local environmental factors, as rates of degradation depend on physical factors, such as levels of ultraviolet light exposure, oxygen and temperature (Swift & Wiles 2004), while biodegradable plastics require the presence of suitable micro-organisms. Therefore, degradation rates vary considerably between landfills, terrestrial and marine environments (Kyrikou & Briassoulis 2007). Even when a plastic item degrades under the influence of weathering, it first breaks down into smaller pieces of plastic debris, but the polymer itself may not necessarily fully degrade in a meaningful timeframe. As a consequence, substantial quantities of end-of-life plastics are accumulating in landfills and as debris in the natural environment, resulting in both waste-management issues and environmental damage (see Barnes et al. 2009; Gregory 2009; Oehlmann et al. 2009; Ryan et al. 2009; Teuten et al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2009b).

Recycling is clearly a waste-management strategy, but it can also be seen as one current example of implementing the concept of industrial ecology, whereas in a natural ecosystem there are no wastes but only products (Frosch & Gallopoulos 1989; McDonough & Braungart 2002). Recycling of plastics is one method for reducing environmental impact and resource depletion. Fundamentally, high levels of recycling, as with reduction in use, reuse and repair or re-manufacturing can allow for a given level of product service with lower material inputs than would otherwise be required. Recycling can therefore decrease energy and material usage per unit of output and so yield improved eco-efficiency (WBCSD 2000). Although, it should be noted that the ability to maintain whatever residual level of material input, plus the energy inputs and the effects of external impacts on ecosystems will decide the ultimate sustainability of the overall system.

In this paper, we will review the current systems and technology for plastics recycling, life-cycle evidence for the eco-efficiency of plastics recycling, and briefly consider related economic and public interest issues. We will focus on production and disposal of packaging as this is the largest single source of waste plastics in Europe and represents an area of considerable recent expansion in recycling initiatives.

2. Waste management: overview

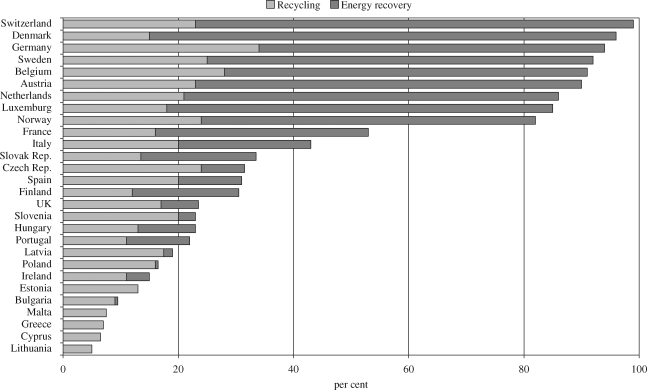

Even within the EU there are a wide range of waste-management prioritizations for the total municipal solid waste stream (MSW), from those heavily weighted towards landfill, to those weighted towards incineration (figure 1)—recycling performance also varies considerably. The average amount of MSW generated in the EU is 520 kg per person per year and projected to increase to 680 kg per person per year by 2020 (EEA 2008). In the UK, total use of plastics in both domestic and commercial packaging is about 40 kg per person per year, hence it forms approximately 7–8% by weight, but a larger proportion by volume of the MSW stream (Waste Watch 2003).

Figure 1.

Rates of mechanical recycling and energy recovery as waste-management strategies for plastics waste in European nations (PlasticsEurope 2008b).

Broadly speaking, waste plastics are recovered when they are diverted from landfills or littering. Plastic packaging is particularly noticeable as litter because of the lightweight nature of both flexible and rigid plastics. The amount of material going into the waste-management system can, in the first case, be reduced by actions that decrease the use of materials in products (e.g. substitution of heavy packaging formats with lighter ones, or downgauging of packaging). Designing products to enable reusing, repairing or re-manufacturing will result in fewer products entering the waste stream.

Once material enters the waste stream, recycling is the process of using recovered material to manufacture a new product. For organic materials like plastics, the concept of recovery can also be expanded to include energy recovery, where the calorific value of the material is utilized by controlled combustion as a fuel, although this results in a lesser overall environmental performance than material recovery as it does not reduce the demand for new (virgin) material. This thinking is the basis of the 4Rs strategy in waste management parlance—in the order of decreasing environmental desirability—reduce, reuse, recycle (materials) and recover (energy), with landfill as the least desirable management strategy.

It is also quite possible for the same polymer to cascade through multiple stages—e.g. manufacture into a re-usable container, which once entering the waste stream is collected and recycled into a durable application that when becoming waste in its turn, is recovered for energy.

(a). Landfill

Landfill is the conventional approach to waste management, but space for landfills is becoming scarce in some countries. A well-managed landfill site results in limited immediate environmental harm beyond the impacts of collection and transport, although there are long-term risks of contamination of soils and groundwater by some additives and breakdown by-products in plastics, which can become persistent organic pollutants (Oehlmann et al. 2009; Teuten et al. 2009). A major drawback to landfills from a sustainability aspect is that none of the material resources used to produce the plastic is recovered—the material flow is linear rather than cyclic. In the UK, a landfill tax has been applied, which is currently set to escalate each year until 2010 in order to increase the incentive to divert wastes from landfill to recovery actions such as recycling (DEFRA 2007).

(b). Incineration and energy recovery

Incineration reduces the need for landfill of plastics waste, however, there are concerns that hazardous substances may be released into the atmosphere in the process. For example, PVC and halogenated additives are typically present in mixed plastic waste leading to the risk of dioxins, other polychlorinated biphenyls and furans being released into the environment (Gilpin et al. 2003). As a consequence primarily of this perceived pollution risk, incineration of plastic is less prevalent than landfill and mechanical recycling as a waste-management strategy. Japan and some European countries such as Denmark and Sweden are notable exceptions, with extensive incinerator infrastructure in place for dealing with MSW, including plastics.

Incineration can be used with recovery of some of the energy content in the plastic. The useful energy recovered can vary considerably depending on whether it is used for electricity generation, combined heat and power, or as solid refuse fuel for co-fuelling of blast furnaces or cement kilns. Liquefaction to diesel fuel or gasification through pyrolysis is also possible (Arvanitoyannis & Bosnea 2001) and interest in this approach to produce diesel fuel is increasing, presumably owing to rising oil prices. Energy-recovery processes may be the most suitable way for dealing with highly mixed plastic such as some electronic and electrical wastes and automotive shredder residue.

(c). Downgauging

Reducing the amount of packaging used per item will reduce waste volumes. Economics dictate that most manufacturers will already use close to the minimum required material necessary for a given application (but see Thompson et al. 2009b, Fig 1). This principle is, however, offset against aesthetics, convenience and marketing benefits that can lead to over-use of packaging, as well as the effect of existing investment in tooling and production process, which can also result in excessive packaging of some products.

(d). Re-use of plastic packaging

Forty years ago, re-use of post-consumer packaging in the form of glass bottles and jars was common. Limitations to the broader application of rigid container re-use are at least partially logistical, where distribution and collection points are distant from centralized product-filling factories and would result in considerable back-haul distances. In addition, the wide range of containers and packs for branding and marketing purposes makes direct take-back and refilling less feasible. Take-back and refilling schemes do exist in several European countries (Institute for Local Self-Reliance 2002), including PET bottles as well as glass, but they are elsewhere generally considered a niche activity for local businesses rather than a realistic large-scale strategy to reduce packaging waste.

There is considerable scope for re-use of plastics used for the transport of goods, and for potential re-use or re-manufacture from some plastic components in high-value consumer goods such as vehicles and electronic equipment. This is evident in an industrial scale with re-use of containers and pallets in haulage (see Thompson et al. 2009b). Some shift away from single-use plastic carrier bags to reusable bags has also been observed, both because of voluntary behaviour change programmes, as in Australia (Department of Environment and Heritage (Australia) 2008) and as a consequence of legislation, such as the plastic bag levy in Ireland (Department of Environment Heritage and Local Government (Ireland) 2007), or the recent banning of lightweight carrier bags, for example in Bangladesh and China.

(e). Plastics recycling

Terminology for plastics recycling is complex and sometimes confusing because of the wide range of recycling and recovery activities (table 2). These include four categories: primary (mechanical reprocessing into a product with equivalent properties), secondary (mechanical reprocessing into products requiring lower properties), tertiary (recovery of chemical constituents) and quaternary (recovery of energy). Primary recycling is often referred to as closed-loop recycling, and secondary recycling as downgrading. Tertiary recycling is either described as chemical or feedstock recycling and applies when the polymer is de-polymerized to its chemical constituents (Fisher 2003). Quaternary recycling is energy recovery, energy from waste or valorization. Biodegradable plastics can also be composted, and this is a further example of tertiary recycling, and is also described as organic or biological recycling (see Song et al. 2009).

Table 2.

Terminology used in different types of plastics recycling and recovery.

| ASTM D5033 definitions | equivalent ISO 15270 (draft) definitions | other equivalent terms |

|---|---|---|

| primary recycling | mechanical recycling | closed-loop recycling |

| secondary recycling | mechanical recycling | downgrading |

| tertiary recycling | chemical recycling | feedstock recycling |

| quaternary recycling | energy recovery | valorization |

It is possible in theory to closed-loop recycle most thermoplastics, however, plastic packaging frequently uses a wide variety of different polymers and other materials such as metals, paper, pigments, inks and adhesives that increases the difficulty. Closed-loop recycling is most practical when the polymer constituent can be (i) effectively separated from sources of contamination and (ii) stabilized against degradation during reprocessing and subsequent use. Ideally, the plastic waste stream for reprocessing would also consist of a narrow range of polymer grades to reduce the difficulty of replacing virgin resin directly. For example, all PET bottles are made from similar grades of PET suitable for both the bottle manufacturing process and reprocessing to polyester fibre, while HDPE used for blow moulding bottles is less-suited to injection moulding applications. As a result, the only parts of the post-consumer plastic waste stream that have routinely been recycled in a strictly closed-loop fashion are clear PET bottles and recently in the UK, HDPE milk bottles. Pre-consumer plastic waste such as industrial packaging is currently recycled to a greater extent than post-consumer packaging, as it is relatively pure and available from a smaller number of sources of relatively higher volume. The volumes of post-consumer waste are, however, up to five times larger than those generated in commerce and industry (Patel et al. 2000) and so in order to achieve high overall recycling rates, post-consumer as well as post-industrial waste need to be collected and recycled.

In some instances recovered plastic that is not suitable for recycling into the prior application is used to make a new plastic product displacing all, or a proportion of virgin polymer resin—this can also be considered as primary recycling. Examples are plastic crates and bins manufactured from HDPE recovered from milk bottles, and PET fibre from recovered PET packaging. Downgrading is a term sometimes used for recycling when recovered plastic is put into an application that would not typically use virgin polymer—e.g. ‘plastic lumber’ as an alternative to higher cost/shorter lifetime timber, this is secondary recycling (ASTM Standard D5033).

Chemical or feedstock recycling has the advantage of recovering the petrochemical constituents of the polymer, which can then be used to re-manufacture plastic or to make other synthetic chemicals. However, while technically feasible it has generally been found to be uneconomic without significant subsidies because of the low price of petrochemical feedstock compared with the plant and process costs incurred to produce monomers from waste plastic (Patel et al. 2000). This is not surprising as it is effectively reversing the energy-intensive polymerization previously carried out during plastic manufacture.

Feedstock recycling of polyolefins through thermal-cracking has been performed in the UK through a facility initially built by BP and in Germany by BASF. However, the latter plant was closed in 1999 (Aguado et al. 2007). Chemical recycling of PET has been more successful, as de-polymerization under milder conditions is possible. PET resin can be broken down by glycolysis, methanolysis or hydrolysis, for example to make unsaturated polyester resins (Sinha et al. 2008). It can also be converted back into PET, either after de-polymerization, or by simply re-feeding the PET flake into the polymerization reactor, this can also remove volatile contaminants as the reaction occurs under high temperature and vacuum (Uhde Inventa-Fischer 2007).

(f). Alternative materials

Biodegradable plastics have the potential to solve a number of waste-management issues, especially for disposable packaging that cannot be easily separated from organic waste in catering or from agricultural applications. It is possible to include biodegradable plastics in aerobic composting, or by anaerobic digestion with methane capture for energy use. However, biodegradable plastics also have the potential to complicate waste management when introduced without appropriate technical attributes, handling systems and consumer education. In addition, it is clear that there could be significant issues in sourcing sufficient biomass to replace a large proportion of the current consumption of polymers, as only 5 per cent of current European chemical production uses biomass as feedstock (Soetaert & Vandamme 2006). This is a large topic that cannot be covered in this paper, except to note that it is desirable that compostable and degradable plastics are appropriately labelled and used in ways that complement, rather than compromise waste-management schemes (see Song et al. 2009).

3. Systems for plastic recycling

Plastic materials can be recycled in a variety of ways and the ease of recycling varies among polymer type, package design and product type. For example, rigid containers consisting of a single polymer are simpler and more economic to recycle than multi-layer and multi-component packages.

Thermoplastics, including PET, PE and PP all have high potential to be mechanically recycled. Thermosetting polymers such as unsaturated polyester or epoxy resin cannot be mechanically recycled, except to be potentially re-used as filler materials once they have been size-reduced or pulverized to fine particles or powders (Rebeiz & Craft 1995). This is because thermoset plastics are permanently cross-linked in manufacture, and therefore cannot be re-melted and re-formed. Recycling of cross-linked rubber from car tyres back to rubber crumb for re-manufacture into other products does occur and this is expected to grow owing to the EU Directive on Landfill of Waste (1999/31/EC), which bans the landfill of tyres and tyre waste.

A major challenge for producing recycled resins from plastic wastes is that most different plastic types are not compatible with each other because of inherent immiscibility at the molecular level, and differences in processing requirements at a macro-scale. For example, a small amount of PVC contaminant present in a PET recycle stream will degrade the recycled PET resin owing to evolution of hydrochloric acid gas from the PVC at a higher temperature required to melt and reprocess PET. Conversely, PET in a PVC recycle stream will form solid lumps of undispersed crystalline PET, which significantly reduces the value of the recycled material.

Hence, it is often not technically feasible to add recovered plastic to virgin polymer without decreasing at least some quality attributes of the virgin plastic such as colour, clarity or mechanical properties such as impact strength. Most uses of recycled resin either blend the recycled resin with virgin resin—often done with polyolefin films for non-critical applications such as refuse bags, and non-pressure-rated irrigation or drainage pipes, or for use in multi-layer applications, where the recycled resin is sandwiched between surface layers of virgin resin.

The ability to substitute recycled plastic for virgin polymer generally depends on the purity of the recovered plastic feed and the property requirements of the plastic product to be made. This has led to current recycling schemes for post-consumer waste that concentrate on the most easily separated packages, such as PET soft-drink and water bottles and HDPE milk bottles, which can be positively identified and sorted out of a co-mingled waste stream. Conversely, there is limited recycling of multi-layer/multi-component articles because these result in contamination between polymer types. Post-consumer recycling therefore comprises of several key steps: collection, sorting, cleaning, size reduction and separation, and/or compatibilization to reduce contamination by incompatible polymers.

(a). Collection

Collection of plastic wastes can be done by ‘bring-schemes’ or through kerbside collection. Bring-schemes tend to result in low collection rates in the absence of either highly committed public behaviour or deposit-refund schemes that impose a direct economic incentive to participate. Hence, the general trend is for collection of recyclable materials through kerbside collection alongside MSW. To maximize the cost efficiency of these programmes, most kerbside collections are of co-mingled recyclables (paper/board, glass, aluminium, steel and plastic containers). While kerbside collection schemes have been very successful at recovering plastic bottle packaging from homes, in terms of the overall consumption typically only 30–40% of post-consumer plastic bottles are recovered, as a lot of this sort of packaging comes from food and beverage consumed away from home. For this reason, it is important to develop effective ‘on-the-go’ and ‘office recycling’ collection schemes if overall collection rates for plastic packaging are to increase.

(b). Sorting

Sorting of co-mingled rigid recyclables occurs by both automatic and manual methods. Automated pre-sorting is usually sufficient to result in a plastics stream separate from glass, metals and paper (other than when attached, e.g. as labels and closures). Generally, clear PET and unpigmented HDPE milk bottles are positively identified and separated out of the stream. Automatic sorting of containers is now widely used by material recovery facility operators and also by many plastic recycling facilities. These systems generally use Fourier-transform near-infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy for polymer type analysis and also use optical colour recognition camera systems to sort the streams into clear and coloured fractions. Optical sorters can be used to differentiate between clear, light blue, dark blue, green and other coloured PET containers. Sorting performance can be maximized using multiple detectors, and sorting in series. Other sorting technologies include X-ray detection, which is used for separation of PVC containers, which are 59 per cent chlorine by weight and so can be easily distinguished (Arvanitoyannis & Bosnea 2001; Fisher 2003).

Most local authorities or material recovery facilities do not actively collect post-consumer flexible packaging as there are current deficiencies in the equipment that can easily separate flexibles. Many plastic recycling facilities use trommels and density-based air-classification systems to remove small amounts of flexibles such as some films and labels. There are, however, developments in this area and new technologies such as ballistic separators, sophisticated hydrocyclones and air-classifiers that will increase the ability to recover post-consumer flexible packaging (Fisher 2003).

(c). Size reduction and cleaning

Rigid plastics are typically ground into flakes and cleaned to remove food residues, pulp fibres and adhesives. The latest generation of wash plants use only 2–3 m3 of water per tonne of material, about one-half of that of previous equipment. Innovative technologies for the removal of organics and surface contaminants from flakes include ‘dry-cleaning’, which cleans surfaces through friction without using water.

(d). Further separation

After size reduction, a range of separation techniques can be applied. Sink/float separation in water can effectively separate polyolefins (PP, HDPE, L/LLDPE) from PVC, PET and PS. Use of different media can allow separation of PS from PET, but PVC cannot be removed from PET in this manner as their density ranges overlap. Other separation techniques such as air elutriation can also be used for removing low-density films from denser ground plastics (Chandra & Roy 2007), e.g. in removing labels from PET flakes.

Technologies for reducing PVC contaminants in PET flake include froth flotation (Drelich et al. 1998; Marques & Tenorio 2000)[JH1], FT-NIR or Raman emission spectroscopic detectors to enable flake ejection and using differing electrostatic properties (Park et al. 2007). For PET flake, thermal kilns can be used to selectively degrade minor amounts of PVC impurities, as PVC turns black on heating, enabling colour-sorting.

Various methods exist for flake-sorting, but traditional PET-sorting systems are predominantly restricted to separating; (i) coloured flakes from clear PET flakes and (ii) materials with different physical properties such as density from PET. New approaches such as laser-sorting systems can be used to remove other impurities such as silicones and nylon.

‘Laser-sorting’ uses emission spectroscopy to differentiate polymer types. These systems are likely to significantly improve the ability to separate complex mixtures as they can perform up to 860 000 spectra s−1 and can scan each individual flake. They have the advantage that they can be used to sort different plastics that are black—a problem with traditional automatic systems. The application of laser-sorting systems is likely to increase separation of WEEE and automotive plastics. These systems also have the capability to separate polymer by type or grade and can also separate polyolefinic materials such as PP from HDPE. However, this is still a very novel approach and currently is only used in a small number of European recycling facilities.

(e). Current advances in plastic recycling

Innovations in recycling technologies over the last decade include increasingly reliable detectors and sophisticated decision and recognition software that collectively increase the accuracy and productivity of automatic sorting—for example current FT-NIR detectors can operate for up to 8000 h between faults in the detectors.

Another area of innovation has been in finding higher value applications for recycled polymers in closed-loop processes, which can directly replace virgin polymer (see table 3). As an example, in the UK, since 2005 most PET sheet for thermoforming contains 50–70% recycled PET (rPET) through use of A/B/A layer sheet where the outer layers (A) are food-contact-approved virgin resin, and the inner layer (B) is rPET. Food-grade rPET is also now widely available in the market for direct food contact because of the development of ‘super-clean’ grades. These only have slight deterioration in clarity from virgin PET, and are being used at 30–50% replacement of virgin PET in many applications and at 100 per cent of the material in some bottles.

Table 3.

Comparing some environmental impacts of commodity polymer production and current ability for recycling from post-consumer sources.

| LCI data cradle-to-gate (EU data) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| polymer | energy (GJ tonne−1) | water (kL tonne−1) | CO2-ea (t tonne−1) | Usageb (ktonne) | closed-loop recycling | effectiveness in current recycling processes |

| PET | 82.7 | 66 | 3.4 | 2160 | yes | high with clear PET from bottles coloured PET is mostly used for fibre additional issues with CPET trays, PET-G |

| HDPE | 76.7 | 32 | 1.9 | 5468 | some | high with natural HDPE bottles, but more complex for opaque bottles and trays because of wide variety of grades and colour and mixtures with LDPE and PP |

| PVC | 56.7 | 46 | 1.9 | 6509 | some | poor recovery because of cross-contamination with PET PVC packages and labels present a major issue with PET bottle and mixed plastics recycling |

| LDPE | 78.1 | 47 | 2.1 | 7899 | some | poor recovery rates, mostly as mixed polyolefins that can have sufficient properties for some applications. Most post-consumer flexible packaging not recovered |

| PP | 73.4 | 43 | 2.0 | 7779 | in theory | not widely recycled yet from post-consumer, but has potential. Needs action on sorting and separation, plus development of further outlets for recycled PP |

| PS | 87.4 | 140 | 3.4 | 2600 | in theory | poor, extremely difficult to cost-effectively separate from co-mingled collection, separate collection of industrial packaging and EPS foam can be effective |

| recycled plastics | 8–55 | typical 3.5c | typical 1.4 | 3130 | some | considerable variability in energy, water and emissions from recycling processes as it is a developing industry and affected by efficiency of collection, process type and product mix, etc. |

a CO2-e is GWP calculated as 100-yr equivalent to CO2 emissions. All LCI data are specific to European industry and covers the production process of the raw materials, intermediates and final polymer, but not further processing and logistics (PlasticsEurope 2008a).

b Usage was for the aggregate EU-15 countries across all market sectors in 2002.

c Typical values for water and greenhouse gas emissions from recycling activities to produce 1 kg PET from waste plastic (Perugini et al. 2005).

A number of European countries including Germany, Austria, Norway, Italy and Spain are already collecting, in addition to their bottle streams, rigid packaging such as trays, tubs and pots as well as limited amounts of post-consumer flexible packaging such as films and wrappers. Recycling of this non-bottle packaging has become possible because of improvements in sorting and washing technologies and emerging markets for the recyclates. In the UK, the Waste Resource Action Programme (WRAP) has run an initial study of mixed plastics recycling and is now taking this to full-scale validation (WRAP 2008b). The potential benefits of mixed plastics recycling in terms of resource efficiency, diversion from landfill and emission savings, are very high when one considers the fact that in the UK it is estimated that there is over one million tonne per annum of non-bottle plastic packaging (WRAP 2008a) in comparison with 525 000 tonnes of plastic bottle waste (WRAP 2007).

4. Ecological case for recycling

Life-cycle analysis can be a useful tool for assessing the potential benefits of recycling programmes. If recycled plastics are used to produce goods that would otherwise have been made from new (virgin) polymer, this will directly reduce oil usage and emissions of greenhouse gases associated with the production of the virgin polymer (less the emissions owing to the recycling activities themselves). However, if plastics are recycled into products that were previously made from other materials such as wood or concrete, then savings in requirements for polymer production will not be realized (Fletcher & Mackay 1996). There may be other environmental costs or benefits of any such alternative material usage, but these are a distraction to our discussion of the benefits of recycling and would need to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Here, we will primarily consider recycling of plastics into products that would otherwise have been produced from virgin polymer.

Feedstock (chemical) recycling technologies satisfy the general principle of material recovery, but are more costly than mechanical recycling, and less energetically favourable as the polymer has to be depolymerized and then re-polymerized. Historically, this has required very significant subsidies because of the low price of petrochemicals in contrast to the high process and plant costs to chemically recycle polymers.

Energy recovery from waste plastics (by transformation to fuel or by direct combustion for electricity generation, use in cement kilns and blast furnaces, etc.) can be used to reduce landfill volumes, but does not reduce the demand for fossil fuels (as the waste plastic was made from petrochemicals; Garforth et al. 2004). There are also environmental and health concerns associated with their emissions.

One of the key benefits of recycling plastics is to reduce the requirement for plastics production. Table 3 provides data on some environmental impacts from production of virgin commodity plastics (up to the ‘factory gate’), and summarizes the ability of these resins to be recycled from post-consumer waste. In terms of energy use, recycling has been shown to save more energy than that produced by energy recovery even when including the energy used to collect, transport and re-process the plastic (Morris 1996). Life-cycle analyses has also been used for plastic-recycling systems to evaluate the net environmental impacts (Arena et al. 2003; Perugini et al. 2005) and these find greater positive environmental benefits for mechanical recycling over landfill and incineration with energy recovery.

It has been estimated that PET bottle recycling gives a net benefit in greenhouse gas emissions of 1.5 tonnes of CO2-e per tonne of recycled PET (Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) 2005) as well as reduction in landfill and net energy consumption. An average net reduction of 1.45 tonnes of CO2-e per tonne of recycled plastic has been estimated as a useful guideline to policy (ACRR 2004), one basis for this value appears to have been a German life-cycle analysis (LCA) study (Patel et al. 2000), which also found that most of the net energy and emission benefits arise from the substitution of virgin polymer production. A recent LCA specifically for PET bottle manufacture calculated that use of 100 per cent recycled PET instead of 100 per cent virgin PET would reduce the full life-cycle emissions from 446 to 327 g CO2 per bottle, resulting in a 27 per cent relative reduction in emissions (WRAP 2008e).

Mixed plastics, the least favourable source of recycled polymer could still provide a net benefit of the vicinity of 0.5 tonnes of CO2-e per tonne of recycled product (WRAP 2008c). The higher eco-efficiency for bottle recycling is because of both the more efficient process for recycling bottles as opposed to mixed plastics and the particularly high emissions profile of virgin PET production. However, the mixed plastics recycling scenario still has a positive net benefit, which was considered superior to the other options studied, of both landfills and energy recovery as solid refuse fuel, so long as there is substitution of virgin polymer.

5. Public support for recycling

There is increasing public awareness on the need for sustainable production and consumption. This has encouraged local authorities to organize collection of recyclables, encouraged some manufacturers to develop products with recycled content, and other businesses to supply this public demand. Marketing studies of consumer preferences indicate that there is a significant, but not overwhelming proportion of people who value environmental values in their purchasing patterns. For such customers, confirmation of recycled content and suitability for recycling of the packaging can be a positive attribute, while exaggerated claims for recyclability (where the recyclability is potential, rather than actual) can reduce consumer confidence. It has been noted that participating in recycling schemes is an environmental behaviour that has wide participation among the general population and was 57 per cent in the UK in a 2006 survey (WRAP 2008d), and 80 per cent in an Australian survey where kerbside collection had been in place for longer (NEPC 2001).

Some governments use policy to encourage post-consumer recycling, such as the EU Directive on packaging and packaging waste (94/62/EC). This subsequently led Germany to set-up legislation for extended producer responsibility that resulted in the die Grüne Punkt (Green Dot) scheme to implement recovery and recycling of packaging. In the UK, producer responsibility was enacted through a scheme for generating and trading packaging recovery notes, plus more recently a landfill levy to fund a range of waste reduction activities. As a consequence of all the above trends, the market value of recycled polymer and hence the viability of recycling have increased markedly over the last few years.

Extended producer responsibility can also be enacted through deposit-refund schemes, covering for example, beverage containers, batteries and vehicle tyres. These schemes can be effective in boosting collection rates, for example one state of Australia has a container deposit scheme (that includes PET soft-drink bottles), as well as kerbside collection schemes. Here the collection rate of PET bottles was 74 per cent of sales, compared with 36 per cent of sales in other states with kerbside collection only. The proportion of bottles in litter was reduced as well compared to other states (West 2007).

6. Economic issues relating to recycling

Two key economic drivers influence the viability of thermoplastics recycling. These are the price of the recycled polymer compared with virgin polymer and the cost of recycling compared with alternative forms of acceptable disposal. There are additional issues associated with variations in the quantity and quality of supply compared with virgin plastics. Lack of information about the availability of recycled plastics, its quality and suitability for specific applications, can also act as a disincentive to use recycled material.

Historically, the primary methods of waste disposal have been by landfill or incineration. Costs of landfill vary considerably among regions according to the underlying geology and land-use patterns and can influence the viability of recycling as an alternative disposal route. In Japan, for example, the excavation that is necessary for landfill is expensive because of the hard nature of the underlying volcanic bedrock; while in the Netherlands it is costly because of permeability from the sea. High disposal costs are an economic incentive towards either recycling or energy recovery.

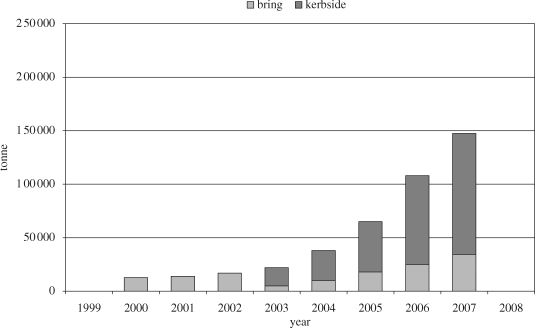

Collection of used plastics from households is more economical in suburbs where the population density is sufficiently high to achieve economies of scale. The most efficient collection scheme can vary with locality, type of dwellings (houses or large multi-apartment buildings) and the type of sorting facilities available. In rural areas ‘bring schemes’ where the public deliver their own waste for recycling, for example when they visit a nearby town, are considered more cost-effective than kerbside collection. Many local authorities and some supermarkets in the UK operate ‘bring banks’, or even reverse-vending machines. These latter methods can be a good source of relatively pure recyclables, but are ineffective in providing high collection rates of post-consumer waste. In the UK, dramatic increases in collection of the plastic bottle waste stream was only apparent after the relatively recent implementation of kerbside recycling (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Growth in collection of plastic bottles, by bring and kerbside schemes in the UK (WRAP 2008d).

The price of virgin plastic is influenced by the price of oil, which is the principle feedstock for plastic production. As the quality of recovered plastic is typically lower than that of virgin plastics, the price of virgin plastic sets the ceiling for prices of recovered plastic. The price of oil has increased significantly in the last few years, from a range of around USD 25 per barrel to a price band between USD 50–150 since 2005. Hence, although higher oil prices also increase the cost of collection and reprocessing to some extent, recycling has become relatively more financially attractive.

Technological advances in recycling can improve the economics in two main ways—by decreasing the cost of recycling (productivity/efficiency improvements) and by closing the gap between the value of recycled resin and virgin resin. The latter point is particularly enhanced by technologies for turning recovered plastic into food grade polymer by removing contamination—supporting closed-loop recycling. This technology has been proven for rPET from clear bottles (WRAP 2008b), and more recently rHDPE from milk bottles (WRAP 2006).

So, while over a decade ago recycling of plastics without subsidies was mostly only viable from post-industrial waste, or in locations where the cost of alternative forms of disposal were high, it is increasingly now viable on a much broader geographic scale, and for post-consumer waste.

7. Current trends in plastic recycling

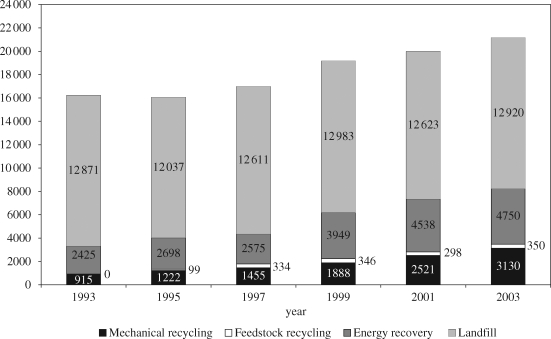

In western Europe, plastic waste generation is growing at approximately 3 per cent per annum, roughly in line with long-term economic growth, whereas the amount of mechanical recycling increased strongly at a rate of approximately 7 per cent per annum. In 2003, however, this still amounted to only 14.8 per cent of the waste plastic generated (from all sources). Together with feedstock recycling (1.7 per cent) and energy recovery (22.5 per cent), this amounted to a total recovery rate of approximately 39 per cent from the 21.1 million tonnes of plastic waste generated in 2003 (figure 3). This trend for both rates of mechanical recycling and energy recovery to increase is continuing, although so is the trend for increasing waste generation.

Figure 3.

Volumes of plastic waste disposed to landfill, and recovered by various methods in Western Europe, 1993–2003 (APME 2004).

8. Challenges and opportunities for improving plastic recycling

Effective recycling of mixed plastics waste is the next major challenge for the plastics recycling sector. The advantage is the ability to recycle a larger proportion of the plastic waste stream by expanding post-consumer collection of plastic packaging to cover a wider variety of materials and pack types. Product design for recycling has strong potential to assist in such recycling efforts. A study carried out in the UK found that the amount of packaging in a regular shopping basket that, even if collected, cannot be effectively recycled, ranged from 21 to 40% (Local Government Association (UK) 2007). Hence, wider implementation of policies to promote the use of environmental design principles by industry could have a large impact on recycling performance, increasing the proportion of packaging that can economically be collected and diverted from landfill (see Shaxson et al. 2009). The same logic applies to durable consumer goods designing for disassembly, recycling and specifications for use of recycled resins are key actions to increase recycling.

Most post-consumer collection schemes are for rigid packaging as flexible packaging tends to be problematic during the collection and sorting stages. Most current material recovery facilities have difficulty handling flexible plastic packaging because of the different handling characteristics of rigid packaging. The low weight-to-volume ratio of films and plastic bags also makes it less economically viable to invest in the necessary collection and sorting facilities. However, plastic films are currently recycled from sources including secondary packaging such as shrink-wrap of pallets and boxes and some agricultural films, so this is feasible under the right conditions. Approaches to increasing the recycling of films and flexible packaging could include separate collection, or investment in extra sorting and processing facilities at recovery facilities for handling mixed plastic wastes. In order to have successful recycling of mixed plastics, high-performance sorting of the input materials needs to be performed to ensure that plastic types are separated to high levels of purity; there is, however, a need for the further development of endmarkets for each polymer recyclate stream.

The effectiveness of post-consumer packaging recycling could be dramatically increased if the diversity of materials were to be rationalized to a subset of current usage. For example, if rigid plastic containers ranging from bottles, jars to trays were all PET, HDPE and PP, without clear PVC or PS, which are problematic to sort from co-mingled recyclables, then all rigid plastic packaging could be collected and sorted to make recycled resins with minimal cross-contamination. The losses of rejected material and the value of the recycled resins would be enhanced. In addition, labels and adhesive materials should be selected to maximize recycling performance. Improvements in sorting/separation within recycling plants give further potential for both higher recycling volumes, and better eco-efficiency by decreasing waste fractions, energy and water use (see §3). The goals should be to maximize both the volume and quality of recycled resins.

9. Conclusions

In summary, recycling is one strategy for end-of-life waste management of plastic products. It makes increasing sense economically as well as environmentally and recent trends demonstrate a substantial increase in the rate of recovery and recycling of plastic wastes. These trends are likely to continue, but some significant challenges still exist from both technological factors and from economic or social behaviour issues relating to the collection of recyclable wastes, and substitution for virgin material.

Recycling of a wider range of post-consumer plastic packaging, together with waste plastics from consumer goods and ELVs will further enable improvement in recovery rates of plastic waste and diversion from landfills. Coupled with efforts to increase the use and specification of recycled grades as replacement of virgin plastic, recycling of waste plastics is an effective way to improve the environmental performance of the polymer industry.

Footnotes

One contribution of 15 to a Theme Issue ‘Plastics, the environment and human health’.

References

- ACRR 2004Good practices guide on waste plastics recycling Brussels, Belgium: Association of Cities and Regions for Recycling [Google Scholar]

- Aguado J., Serrano D. P., San Miguel G.2007European trends in the feedstock recycling of plastic wastes. Global NEST J. 9, 12–19 [Google Scholar]

- Andrady A.1994Assessment of environmental biodegradation of synthetic polymers. Polym. Rev. 34, 25–76 (doi:10.1080/15321799408009632) [Google Scholar]

- Andrady A.2003An environmental primer. In Plastics and the environment (ed. Andrady A.), pp. 3–76 Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Interscience [Google Scholar]

- Andrady A. L., Neal M. A.2009Applications and societal benefits of plastics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1977–1984 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APME 2004An analysis of plastics consumption and recovery in Europe Brussels, Belgium: Association of Plastic Manufacturers Europe [Google Scholar]

- Arena U., Mastellone M., Perugini F.2003Life cycle assessment of a plastic packaging recycling system. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 8, 92–98 (doi:10.1007/BF02978432) [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitoyannis I., Bosnea L.2001Recycling of polymeric materials used for food packaging: current status and perspectives. Food Rev. Int. 17, 291–346 (doi:10.1081/FRI-100104703) [Google Scholar]

- ASTM Standard D5033 2000 Standard guide to development of ASTM standards relating to recycling and use of recycled plastics West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International; (doi:10.1520/D5033-00) [Google Scholar]

- British Plastics Federation. Oil consumption. 2008. See http://www.bpf.co.uk/Oil_Consumption.aspx. (20 October 2008)

- Barnes D. K. A., Galgani F., Thompson R. C., Barlaz M.2009Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1985–1998 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0205) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda M., Roy S.2007Plastics technology handbook 4th edn Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- DEFRA 2007Waste strategy factsheets. See http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/waste/strategy/factsheets/landfilltax.htm (26 November 2008)

- Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) 2005Benefits of recycling Australia: Parramatta [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment and Heritage (Australia) 2008Plastic bags. See http://www.ephc.gov.au/ephc/plastic_bags.html (26 November 2008)

- Department of Environment Heritage and Local Government (Ireland) 2007Plastic bags. See http://www.environ.ie/en/Environment/Waste/PlasticBags (26 November 2008)

- Drelich J., Payne J., Kim T., Miller J.1998Selective froth floatation of PVC from PVC/PET mixtures for the plastics recycling industry. Polym. Eng. Sci. 38, 1378 (doi:10.1002/pen.10308) [Google Scholar]

- EEA 2008Better management of municipal waste will reduce greenhouse gas emissions Copenhagen, Denmark: European Environment Agency [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M.2003Plastics recycling. In Plastics and the environment (ed. Andrady A.), pp. 563–627 Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Interscience [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher B., Mackay M.1996A model of plastics recycling: does recycling reduce the amount of waste? Resour. Conserv. Recycling 17, 141–151 (doi:10.1016/0921-3449(96)01068-3) [Google Scholar]

- Frosch R., Gallopoulos N.1989Strategies for manufacturing. Sci. Am. 261, 144–152 [Google Scholar]

- Garforth A., Ali S., Hernandez-Martinez J., Akah A.2004Feedstock recycling of polymer wastes. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 8, 419–425 (doi:10.1016/j.cossms.2005.04.003) [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin R., Wagel D., Solch J.2003Production, distribution, and fate of polycholorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins, dibenzofurans, and related organohalogens in the environment. In Dioxins and health (eds Schecter A., Gasiewicz T.), 2nd edn Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc [Google Scholar]

- Gregory M. R.2009Environmental implications of plastic debris in marine settings—entanglement, ingestion, smothering, hangers-on, hitch-hiking and alien invasions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2013–2025 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Local Self-Reliance 2002Western Europe's experience with refillable beverage containers. See http://www.grrn.org/beverage/refillables/Europe.html (26 November 2008)

- Kyrikou I., Briassoulis D.2007Biodegradation of agricultural plastic films: a critical review. J. Polym. Environ. 15, 125–150 (doi:10.1007/s10924-007-0053-8) [Google Scholar]

- Local Government Association (UK) 2007War on waste: food packaging study UK: Local Government Authority [Google Scholar]

- Marques G., Tenorio J.2000Use of froth flotation to separate PVC/PET mixtures. Waste Management 20, 265–269 (doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(99)00333-5) [Google Scholar]

- McDonough W., Braungart M.2002Cradle to cradle: remaking the way we make things New York, NY: North Point Press [Google Scholar]

- Morris J.1996Recycling versus incineration: an energy conservation analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 47, 277–293 (doi:10.1016/0304-3894(95)00116-6) [Google Scholar]

- NEPC 2001Report to the NEPC on the implementation of the National Environment Protection (used packaging materials) measure for New South Wales. Adelaide, Australia: Environment Protection and Heritage Council [Google Scholar]

- Oehlmann J., et al. 2009A critical analysis of the biological impacts of plasticizers on wildlife. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2047–2062 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0242) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.-H., Jeon H.-S., Park K.2007PVC removal from mixed plastics by triboelectrostatic separation. J. Hazard. Mater. 144, 470–476 (doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.10.060) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., von Thienen N., Jochem E., Worrell E.2000Recycling of plastics in Germany. Resour., Conserv. Recycling 29, 65–90 (doi:10.1016/S0921-3449(99)00058-0) [Google Scholar]

- Perugini F., Mastellone M., Arena U.2005A life cycle assessment of mechanical and feedstock recycling options for management of plastic packaging wastes. Environ. Progr. 24, 137–154 (doi:10.1002/ep.10078) [Google Scholar]

- PlasticsEurope 2008aEco-profiles of the European Plastics Industry. Brussels, Belgium: PlasticsEurope; See http://lca.plasticseurope.org/index.htm (1 November 2008) [Google Scholar]

- PlasticsEurope 2008bThe compelling facts about Plastics 2007: an analysis of plastics production, demand and recovery for 2007 in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: PlasticsEurope [Google Scholar]

- Rebeiz K., Craft A.1995Plastic waste management in construction: technological and institutional issues. Resour., Conserv. Recycling 15, 245–257 (doi:10.1016/0921-3449(95)00034-8) [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P. G., Moore C. J., van Franeker J. A., Moloney C. L.2009Monitoring the abundance of plastic debris in the marine environment. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1999–2012 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0207) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaxson L.2009Structuring policy problems for plastics, the environment and human health: reflections from the UK. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2141–2151 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0283) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha V., Patel M., Patel J.2008PET waste management by chemical recycling: a review. J. Polym. Environ. (doi:10.1007/s10924-008-0106-7) [Google Scholar]

- Soetaert W., Vandamme E.2006The impact of industrial biotechnology. Biotechnol. J. 1, 756–769 (doi:10.1002/biot.200600066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J. H., Murphy R. J., Narayan R., Davies G. B. H.2009Biodegradable and compostable alternatives to conventional plastics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2127–2139 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift G., Wiles D.2004Degradable polymers and plastics in landfill sites. Encyclopedia Polym. Sci. Technol. 9, 40–51 [Google Scholar]

- Teuten E. L., et al. 2009Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2027–2045 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0284) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. C., Swan S. H., Moore C. J., vom Saal F. S.2009aOur plastic age. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 1973–1976 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0054) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. C., Moore C. J., vom Saal F. S., Swan S. H.2009bPlastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2153–2166 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhde Inventa-Fischer 2007Flakes-to-resin (FTR)—recycling with FDA approval. See http://www.uhde-inventa-fischer.com/ (3 November 2008)

- Waste Watch 2003Plastics in the UK economy London, UK: Waste Watch & Recoup [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD 2000Eco-efficiency: creating more value with less impact. See http://www.wbcsd.org/includes/getTarget.asp?type=d&id=ODkwMQ (1 November 2008)

- West D.2007Container deposits: the common sense approach v.2.1 Sydney, Australia: The Boomerang Alliance [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2006WRAP food grade HDPE recycling process: commercial feasibility study London, UK: Waste & Resources Action Programme [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2007. In Annual local authorities Plastics Collection Survey 2007 London, UK: Waste Reduction Action Plans [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2008aDomestic mixed plastics packaging: waste management options London, UK: Waste & Resources Action Programme [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2008bLarge-scale demonstration of viability of recycled PET (rPET) in retail packaging. http://www.wrap.org.uk/retail/case_studies_research/rpet_retail.html.

- WRAP 2008cLCA of management options for mixed waste plastics London, UK: Waste & Resources Action Programme, MDP017 [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2008dLocal authorities Plastics Collection Survey London, UK: Waste & Resources Action Programme [Google Scholar]

- WRAP 2008eStudy reveals carbon impact of bottling Australian wine in the UK in PET and glass bottles. See http://www.wrap.org.uk/wrap_corporate/news/study_reveals_carbon.html (19 October 2008)