Abstract

The partitioning behavior of a series of perhydrocarbon nicotinic acid esters (nicotinates) between aqueous solution and dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) membrane bilayers is investigated as a function of increasing alkyl chain length. The hydrocarbon nicotinates represent putative prodrugs, derivatives of the polar drug nicotinic acid, whose functionalization provides the hydrophobic character necessary for pulmonary delivery in a hydrophobic, fluorocarbon solvent, such as perfluorooctyl bromide. Independent techniques of differential scanning calorimetry and 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5 hexatriene (DPH) fluorescence anisotropy measurements are used to analyze the thermotropic phase behavior and lipid bilayer fluidity as a function of nicotinate concentration. At increasing concentrations of nicotinates over the DPPC mole fraction range examined (XDPPC = 0.6 – 1.0), all the nicotinates (ethyl (C2H5); butyl (C4H9); hexyl (C6H13); and octyl (C8H17)) partition into the lipid bilayer at sufficient levels to eliminate the pretransition, and decrease and broaden the gel to fluid phase transition temperature. The concentration at which these effects occur is chain length-dependent; the shortest chain nicotinate, C2H5, elicits the least dramatic response. Similarly, the DPH anisotropy results demonstrate an alteration of the bilayer organization in the liposomes as a consequence of the chain length-dependent partitioning of the nicotinates into DPPC bilayers. The membrane partition coefficients (logarithm values), determined from the depressed bilayer phase transition temperatures, increase from 2.18 for C2H5 to 5.25 for C8H17. The DPPC membrane/water partitioning of the perhydrocarbon nicotinate series correlates with trends in the octanol/water partitioning of these solutes, suggesting that their incorporation into the bilayer is driven by increasing hydrophobicity.

Keywords: perhydrocarbon nicotinate, DPPC bilayers, prodrug, membrane partition coefficient

Introduction

Nicotinic acid is a polar drug molecule widely recognized for its many pharmaceutical benefits. Used as a food supplement, it is a precursor to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NADP [1]; coenzymes which are important in metabolic cellular function. As a result it has potential in the treatment of lung injury associated with anticancer agent therapies [2] and reduction of the inhibitory respiratory effects caused by bacterial toxins [3]. Extensive clinical studies have established nicotinic acid as a critical agent in preventing or lowering the risk of cardiovascular or coronary heart disease [4-7]. Nicotinic acid raises the level of high density lipoproteins (“good fats”) while reducing low density lipoproteins levels and triglycerides, which are critical factors in the fight against coronary heart disease [6]. Other studies suggest the therapeutic potential of nicotinic acid in the treatment of HIV [8] and the treatment of skin carcinogenesis [9]. The numerous clinical benefits provide incentive to develop a range of administration techniques for this pharmaceutical agent. The need for alternative delivery methods is highlighted by potential dose related side effects; negative pharmaceutical effects of nicotinic acid such as hepatic toxicity have been attributed to the administration formulations such as those with slow release mechanisms [10].

To this end, the delivery of nicotinic acid directly to the lung in the form of prodrugs using a fluorocarbon fluid is of interest as an alternative administration technique [11]. The prodrug approach, where the bioactive drug compound is affixed with a promoiety to facilitate solubility and aid transport in vivo, is a widely accepted method in drug delivery [12]. Fluorocarbons, characterized by biological inertness and chemical stability, low surface tension, high fluidity with high gas dissolution capacity (CO2 and O2) have found potential use in a variety of biomedical applications [13, 14]. Previously, our group, established the viability of pulmonary drug transport of nicotinic acid in cell culture studies using the prominent fluorocarbon fluid, perfluorooctyl bromide (PFOB) [11] as the drug delivery vehicle. To achieve this novel drug delivery method [15, 16], the polar nicotinic acid was functionalized with hydrocarbon and fluorinated side chains to facilitate solubility in the non-polar, lipophobic and hydrophobic PFOB [11, 15, 17]. Application of this liquid ventilation technique for drug delivery has several advantages over conventional drug delivery therapies, which include higher doses to the targeted site and less systemic distribution [15]. The chemically modified compounds or putative prodrugs or nicotinic acid esters (nicotinates) lack clinical activity and are enzymatically converted to the parent nicotinic acid drug at the intended lung site, after passive diffusion through several solvent layers. Homologous series of the prodrugs or nicotinates were synthesized with functional carbon chain lengths from C1 – C8 for both hydrocarbon and fluorinated nicotinates to establish the relationship between chain length and effective delivery [11]. Delivery of the prodrugs to human lung cells in culture using PFOB was demonstrated through the elevated levels of NAD and NADP that were achieved following exposure to the nicotinates. The nicotinates, especially the hydrocarbon analogues (perhydrocarbon nicotinates) could be delivered at sufficient levels to register the desired pharmaceutical response without significant inhibitory effects on cell viability, as measured by corresponding cytotoxicity studies. A chain length-related trend in cytotoxicity was evident for the perhydrocarbon nicotinates when delivered from an aqueous buffer to the cells, with the shortest chain being the least toxic.

The systemic uptake of the prodrugs through a cellular matrix can also be described by models which utilize parameters of thermodynamic partitioning. Partitioning trends through isotropic solvent layers that represent the barrier domains in the passive diffusion of the nicotinates to the targeted site serve as useful indicators of the transport limitations of this system. To this end, the partitioning of the solute prodrugs between immiscible liquid phases was measured experimentally: PFOB/water and perfluoromethylcyclohexane (PFMCH)/toluene (an accepted measure of the fluorophilicity of the solute, or its preference for the fluorocarbon phase) [18]. The octanol/water partition coefficients, a traditional index of the nicotinates' lipophilicities and propensity to distribute into membrane bilayers, were also computed using Advanced Chemistry Development software package (Ontario, Canada) [11]. As expected, the lipophilicity of the nicotinates increased with alkyl chain length of the nicotinates. Also, with increasing chain length of the nicotinates (C1 – C6), the tendency to partition to the fluorocarbon phase from the corresponding immiscible aqueous or hydrocarbon phase also increases [11]. The converse trend was observed for fluorophilicity, which decreased with the chain length of the perhydrocarbon nicotinates.

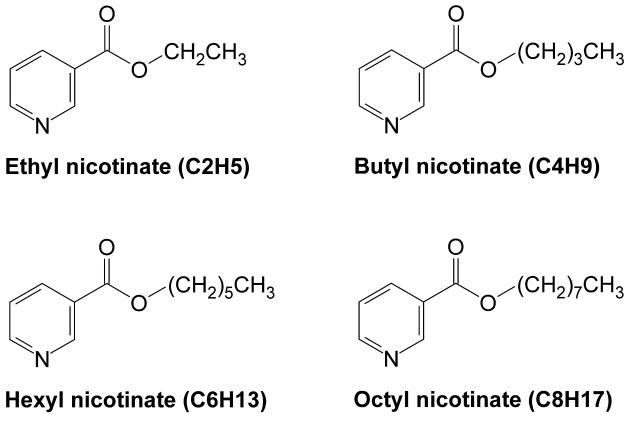

This work examines the effect of increasing chain length of the perhydrocarbon nicotinates (ethyl nicotinate, (C2H5), butyl nicotinate (C4H9), hexyl nicotinate (C6H13) and octyl nicotinate (C8H17), Figure 1) on dissolution in DPPC lipid bilayers and lipid bilayer organization using independent calorimetric (DSC) and fluorescence probe techniques. As constituents of pulmonary surfactant found in lung alveoli, 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerol-3- phosphatidylcholine (DPPC) lipid bilayers were the prime choice as the model membranes in this study and are frequently investigated in membrane partitioning studies of toxins and pharmaceutical agents [19, 20]. Differential scanning calorimetry informs on changes in pretransition and main transition of DPPC bilayers as a function of nicotinate concentration. Alternatively, the membrane fluidity or microviscosity, is assessed by DPH fluorescence anisotropy in liposome bilayers, where changes in the characteristic gel to fluid phase transition and the corresponding transition width are measures of the solute incorporation in the membrane matrix [21-23]. The effects of the incorporation of prodrugs in the membrane bilayers as a function of alkyl chain length and concentration are discussed relative to their previously established physicochemical properties (partitioning behavior in immiscible solvent systems) and observed cytotoxicity trends [11].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the perhydrocarbon nicotinates.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The structure of the nicotinic acid ester prodrugs (nicotiantes) used in this study is provided in Figure 1. C2H5 (Across Chemicals, NJ), C4H9 (Sigma Chemicals Co, MO) and C6H13 (Sigma Chemicals Co, MO) were purified by Kugelrohr distillation to yield the respective nicotinate as colorless liquid. The purity of the nicotinates (> 98%) was confirmed by chromatographic and spectrometric techniques. C8H17 was synthesized by the addition of anhydrous dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and dimethylaminopyridine to a mixture of nicotinic acid and 1-octanol in anhydrous dichloromethane as described previously [17, 24]. The product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using hexane as eluent to give C8H17 as a colorless liquid in 87% yield (> 98% purity). 1H (300 MHz, CDCl3) : 0.85 (bs, -CH3, 3H), 1.24 (bs, 5 × -(CH2)2-, 10H), 1.76 (bs, -OCH2CH2-, 2H), 4.31 (t, -OCH2-, 2H, J = 6.6Hz), 7.30 (d, ArH, J = 4.8Hz, 1H), 8.27 (bs, ArH, 1H), 8.74 (bs, ArH, 1H), 9.20 (bs, ArH, 1H). 13C (100 MHz, CDCl3): 14.25, 22.82, 26.17, 28.81, 29.4 (2 × -CH2-), 31.76, 31.95, 65.74, 123.40, 137.14, 151.08, 153.47, 165.47. GC-MS, m/z (relative intensity, %): 234 (C14H21NO2 +, 8), 220 (4), 206 (11), 192 (29), 178 (24), 164 (37), 151 (16), 137 (19), 124 (100), 106 (90), 78 (80), 51 (38). Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) (purity ≥ 99%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and the fluorescent probe, 1,6-diphenyl-1,3,5-hexatriene (DPH), was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Fisher Scientific supplied ACS grade chloroform, tetrahydrofuran and the deionized, ultra-filtrated water.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Mixtures of DPPC (450 mM DPPC) and nicotinate, prepared in a mole fraction range of 0.6 – 1.0 (X DPPC), were initially dissolved in chloroform. The solvent was gently evaporated under a low pressure nitrogen stream to form an even dry film. The film was further dried under vacuum to remove any trace solvents. The samples were subsequently hydrated with deionized ultra-filtrated (DIUF) water (thrice the weight of the sample). Samples were then subjected to eight cycles of heating (≈ 50 – 55 °C) above the DPPC phase transition temperature of 41 °C [25], for 5 minutes and vortexing for 2 minutes. To minimize evaporative effects when preparing mixtures containing the lowest molecular weight nicotinate (C2H5), the procedure was altered slightly: aqueous solutions of the ethyl nicotinate were added in the appropriate proportion to dried lipid films of pure DPPC prior to the heating and vortexing cycles. The resulting DPPC/nicotinate samples were weighed into aluminum hermetic pans and analyzed on a Thermal Analysis 2920 differential scanning calorimeter. Dry nitrogen was supplied at 60 mL/min when purging the DSC cell and at 120 mL/min when cooling the DSC cell using the refrigerated cooling system. All experiments were carried out in triplicate. Samples were cooled to 10 °C and heated from 10 – 80 °C at 10 °C/min. maximum, onset, offset and peak widths of the main phase transition and pretransition were determined using the in-built Universal Analysis software.

Fluorescence Anisotropy Measurements

Following the method of Bangham et al. [26], evenly dried lipid films of DPPC and DPH in 500:1 molar ratios were prepared by initially dissolving 36.7 mg (1 mM) of DPPC in chloroform (2 ml) with addition of 1 ml of a 0.1 mM DPH/tetrahydrofuran solution in a round bottom flask. The mixed solution was then evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen or a rotary evaporator and further dried under vacuum for at least 4 hours to remove any residual solvents. The dried lipid films were subsequently hydrated with 45 ml DIUF and heated (55-60 °C) above the lipid's phase transition temperature (DPPC Tm = 41 °C [25]) for an hour. Vigorous shaking was carried out at the same temperature range for one hour to form liposomes, followed by repeated extrusion (19 cycles) through 200 nm polycarbonate membranes (Aventis mini extruder, Ottawa, Canada) at a temperature greater than the phase transition temperature to generate small unilamellar liposomes [27]. The resulting liposomes were diluted 10-fold for fluorescence analysis in a custom made stainless steel variable volume view cell (10- 25 ml) designed by Thar Technologies (Pittsburgh, PA). The cell was temperature controlled with an Omega unit (model CN9000A) fitted with heating tape and the liposome suspension was stirred continuously with a magnetic stirrer to maintain uniform temperature. The DPH probe was excited at λex = 350 nm and λem = 452 nm and steady state measurements of the manually polarized light (both excitation and emission) were recorded using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Walnut Creek, CA) [28]. An excitation slit width of 5 nm and emission slit width of 10 nm was used with 1 s average sampling time. An average of five anisotropy measurements was recorded at 1 K intervals on the cooling cycle (50 °C to 25 °C) at approximately 0.17K/min. The fluorescence anisotropy is given in equation (1):

| (Equation 1) |

where I represents the fluorescence intensity, and the subscripts, V and H refer to polarized light in the vertical and horizontal direction. G (grating factor) is the ratio of the vertical to horizontal polarized light and accounts for the sensitivity of the instrument to polarized light [29]. The temperatures scans were carried out twice to ensure reproducibility and verify integrity of the liposomal structure.

Calculation of Solute Partition Coefficient

The apparent partition coefficient of the nicotinates between the bulk aqueous phase and the DPPC membrane bilayer, Km/w was calculated as shown in Equation (2) [30].

| (Equation 2) |

where ΔTm is the change in melting temperature with the addition of nicotinates relative to the pure DPPC liposome solution, Tm is the melting temperature of pure DPPC (315 K), ΔHDPPC is the phase transition enthalpy (31.4 kJ/mol) [31], R is the gas constant, K m/w, the membrane-water partitioning, CDPPC is the lipid concentration and Cs is the concentration of the nicotinates in the bulk solution. The equation is based on the assumption of the depression in Tm (or ΔTm) being in direct proportion to the amount of nicotinate partitioned into the membrane bilayer at equilibrium. The membrane partition coefficient is determined from Eq. 2 using a linear regression of ΔTm versus nicotinate concentration, Cs.

Results

Differential Scanning Calorimetric Measurements

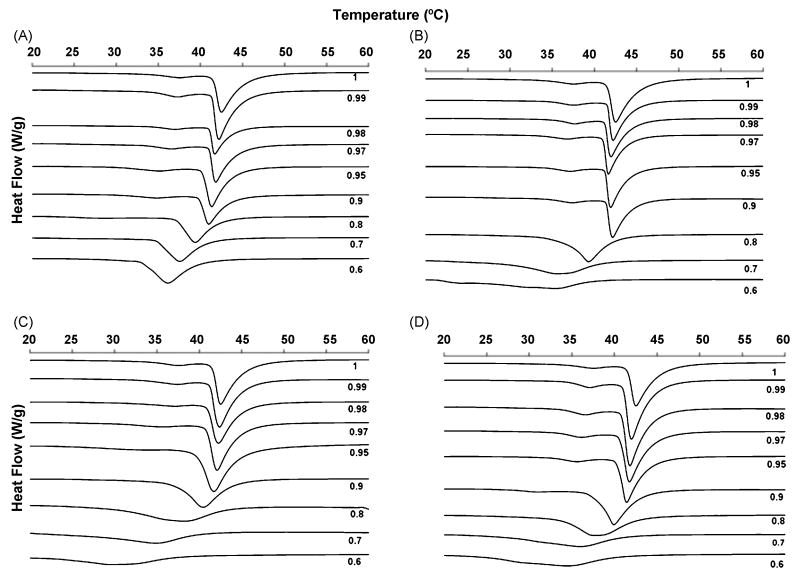

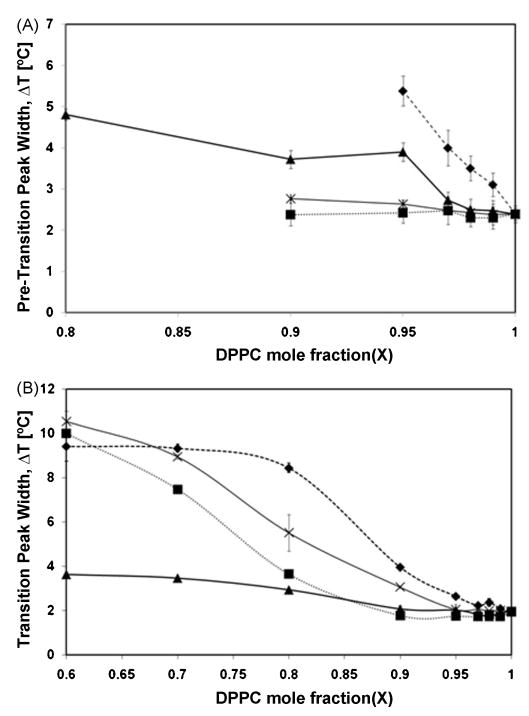

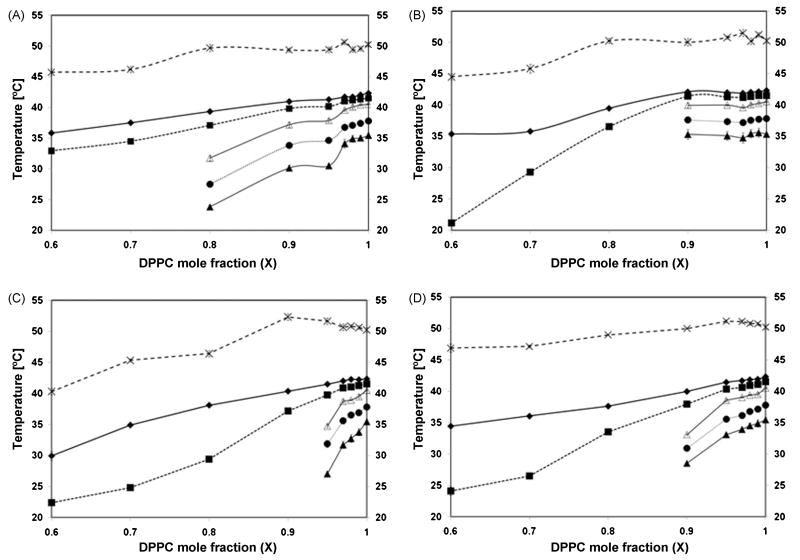

Calorimetric scans were performed for the nicotinate/DPPC mixtures over the range of XDPPC = 0.6 - 1.0 for the following nicotinates: C2H5, C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17. Representative calorimetric scans/thermograms, associated partial phase diagrams and changes in DPPC transition peak width are provided in Figures 2-4. Figure 2 provides the calorimetric scans of the DPPC/nicotinate mixtures; Fig. 3 reports the DPPC pretransition and main transition property changes with increasing nicotinate concentration and Fig. 4 shows expansion of pretransition and main transition width with concentration. The pure DPPC melting temperature or main phase transition temperature (Tm) is characterized by an endothermic peak at 42.55±0.15 °C. The corresponding onset (To), offset (Tf) and transition width (ΔTm) are recorded at 41.57±0.07 °C, 50.25±0.1 °C and 1.96±0.07 °C, respectively. The pure DPPC pretransition exists in the temperature range of 35.41±0.09 °C (onset temperature (Tp,o)) to 40.53±0.10 °C at the offset (Tp,f); the enthalpic peak or endotherm maximum of the pretransition temperature (Tp) occurs at 37.77±0.07 °C, with a corresponding pretransition temperature width (ΔTP) of 2.49±0.14 °C. The measurements are in agreement with published values for DPPC bilayers [22, 23]. Overall, the presence of the nicotinates decreased or eliminated the pretransition, decreased the melting temperature and increased the width of the main phase transition. The shortest chained nicotinate, C2H5, has the least disruptive effect on the bilayer lipid chain organization, as the pretransition is evident at DPPC mole fractions as low as XDPPC = 0.8 (Fig. 2A), below which it is eliminated. The decrease in the pretransition temperature (Fig. 3A) and the corresponding increase in the width of the pretransition (Fig. 4A) is not appreciable until the mole fraction of DPPC falls below 0.97 (XDPPC ≤ 0.97; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the main transition properties remain fairly constant in the same concentration range of XDPPC ≥ 0.97, after which a linear decrease in the enthalpy peak/DPPC melting temperature, Tm, and onset, To, of the transition is observed with increasing mole fractions of the nicotinate (or decreasing XDPPC). The width of the phase transition, ΔTm, in Fig. 4B appears constant for XDPPC≥ 0.9, at which point it increases continually with incremental amounts of nicotinate. Aside from the broadening, there is no deviation or anomaly in peak shape (Fig. 2A) from that of pure DPPC, which implies absence of complex phase behavior with the DPPC-C2H5 mixture.

Figure 2.

Typical calorimetric scans for mixtures of DPPC with (A) Ethyl nicotinate - C2H5, (B) Butyl nicotinate – C4H9, (C) Hexyl nicotinate – C6H13 and (D) Octyl nicotinate – C8H17 in excess water. The mole fraction of DPPC is indicated beside each scan.

Figure 4.

Half width of the (A) pretransition and (B) main phase transition of DPPC with (▲) C2H5, (■) C4H9, (◆) C6H13 and (×) C8H17. All data points represent average of three experiments ± SD.

Figure 3.

Partial phase diagrams of mixtures of DPPC with (A) C2H5, (B) C4H9, (C) C6H13 and (D) C8H17 in excess water. All data points are average of three experiments ± SD. (■) Onset temperature of main transition; (◆) DPPC melting temperature, Tm; (×) offset temperature of main transition; (▲) onset temperature of pretransition; (●) DPPC pretransition temperature, Tp; and (Δ) offset temperature of pretransition.

The pretransition is more sensitive to the presence of C4H9 relative to C2H5, and is eliminated at a lower concentration of C4H9 (or a corresponding higher concentration of DPPC (XDPPC < 0.9) in the DPPC-C4H9 mixtures (Figs. 2B and 3B). There was minimal variance in pretransition properties (onset, offset, peak maximum) in the concentration range over which a pretransition was observed (XDPPC = 1 - 0.9; Figs. 3B and 4A). The main transition onset, To and melting temperature, Tm also appear fairly constant in this composition range. However, a steep decline is evident in To values for XDPPC < 0.9, while a less pronounced decrease is observed in Tm for the same mole fraction range (Fig. 3B). The sigmoidal shape of the width of the main transition, ΔTm, as a function of C4H9 concentration (with a rapid broadening of the peak at XDPPC< 0.9) (Fig. 4B), suggests that the solubilization of the C4H9 drastically influences acyl chain order. At the lowest DPPC mole fraction measured (XDPPC = 0.6), the thermogram peak shape (Fig. 2B) is clearly distorted and two shoulders are observed in the main phase transition endotherm (at 24.1 and 32.5 °C), indicating phase changes or complex phase behavior.

C6H13 has the most destabilizing effect on the pretransition of the nicotinates studied, completely eliminating this transition at DPPC mole fractions below 0.95 (Fig. 2C). A continual decrease in pretransition temperature (Fig. 3C) (onset, offset and peak maximum) and corresponding increase in its width (Fig. 4A) is observed with increasing C6H13 concentration, until the pretransition is eliminated at XDPPC = 0.95. The main phase transition temperature decreases for the entire mole fraction range investigated (XDPPC = 1 – 0.6) (Fig. 3C) and the phase change broadens significantly at XDPPC <0.8 (Fig. 4B). In addition, a shoulder at 18 °C is observed in the thermogram for the mixture at XDPPC = 0.7. The main transition onset, To, and offset, Tp, both decrease with increase in nicotinate concentration (XDPPC = 1 – 0.6) with the decrease more pronounced in the former.

In the case of C8H17, the longest chain nicotinate investigated, the pretransition endotherm is distinctly visible from XDPPC = 0.9 – 1.0, after which it disappears with increasing nicotinate concentration (Fig. 2D). The pretransition onset, offset and temperature demonstrate a similar trend to that of C6H13 for the range over which it is observed (XDPPC = 0.9 -1.0). Surprisingly, however, the pretransition width, ΔTp, displays a similar trend to C4H9 in Fig. 4A, that is it varies little with concentration for the range observed. The onset of the main phase transition, To, exhibits a steeper decrease than Tm for XDPPC ≤ 0.8 (i.e., with increasing nicotinate concentration) (Fig. 3D). The peak width of the main phase transition increases from 1.96 °C at pure DPPC to 10.6 °C at the highest mole fraction of nicotinate, XDPPC = 0.6, the highest increase observed for all the nicotinates. A shoulder in the main transition endotherm was recorded at 30 °C for the lowest mole fraction of DPPC. The offset of the main transition endotherm exhibits the least variation for the whole concentration range of all the nicotinates in this study.

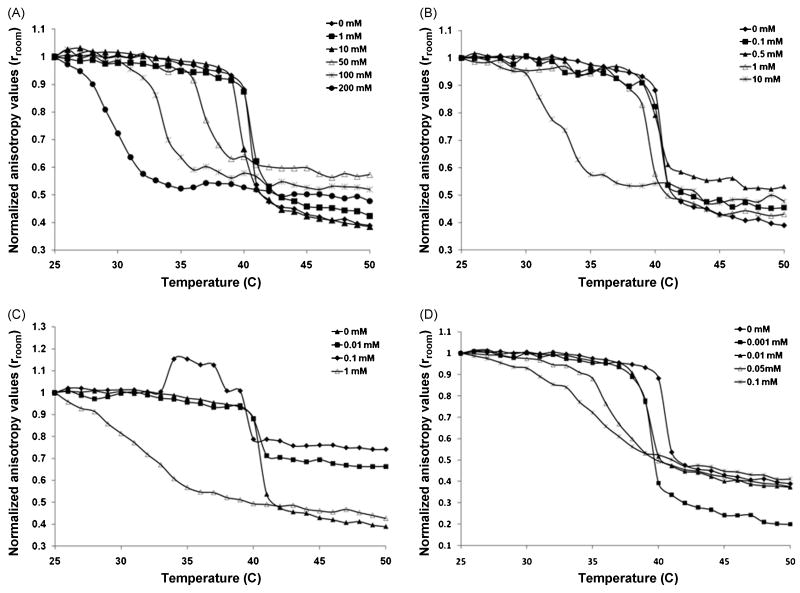

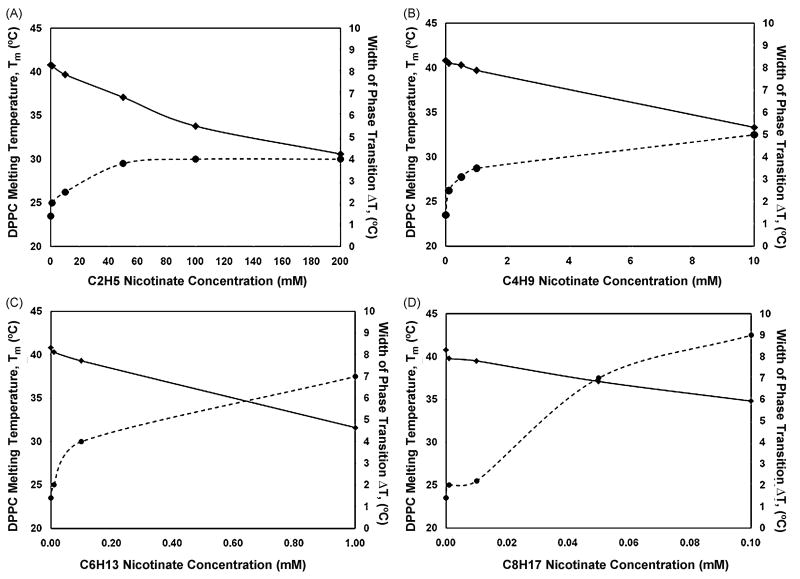

Fluorescence Anisotropy Measurements (DPH)

The anisotropy of the probe molecule in the bilayers of DPPC liposomes (0.1 mM) was measured from 25 - 50 °C for all the four perhydrocarbon nicotinate-DPPC mixtures at various molar concentration ranges. The normalized anisotropy (with respect to the anisotropy value at 25 °C) as a function of temperature is presented in Figure 5. The melting point or phase transition temperatures, Tm, were determined from the inflection point of the anisotropy curves.

Figure 5.

Normalized anisotropy of DPH fluorescent probe in DPPC bilayers as a function of temperature and varying nicotinate concentrations for (A) C2H5 (B) C4H9 (C) C6H13 and (D) C8H17.

DPH anisotropy is a measure of the membrane fluidity and decreases with temperature as the bilayer becomes more disordered. In pure DPPC liposomal systems, the bilayer gel to fluid phase change or chain melting is marked by a sharp transition at Tm =40.8 °C over a 1.4 °C temperature range (width of the phase transition, ΔTr). Here, ΔTmin Eq. (2) is distinguished from ΔTr; the former represents the decrease in the melting temperature while the latter is the change in the gel to fluid phase transition width, both measured by DPH anisotropy. The phase transition width, ΔTr is a measure of the cooperativity of the melting process. The anisotropy data are graphically presented for all the nicotinates in Fig. 5 while Fig. 6 provides a trend of the changes in Tm and transition width ΔTm with nicotinate concentration. The raw anisotropy data are presented as normalized values.

Figure 6.

Melting temperature, Tm(◆) and phase transition width, ΔTr (●) of the DPPC phase transition as function of concentrations of (A) C2H5, (B) C4H9, (C) C6H13 and (D) C8H17 measured by DPH fluorescence anisotropy.

The effect of solubilization of ethyl nicotinate, C2H5, on gel to fluid phase transition, Tm of DPPC bilayers was investigated up to concentrations of 200 mM C2H5 (Fig. 5A). A reduction of Tm, (to 37.1°C) and increase in the phase transition width, ΔTr (to 3.8 °C) is observed at 50 mM (Fig. 6A). At the highest concentration, 200 mM, there is a significant drop in Tm (to 30.6 °C) but the gel to fluid phase width, ΔTr only increases to 4°C from the pure DPPC width of 1.4°C. The anisotropy curves also demonstrate significant deviation from that of pure DPPC with 200 mM of C2H5. Although the curves for the intermediate concentrations, 50 and 100 mM are similar in shape in Fig. 5A, there is a distinct shift in the transition temperature which is shown in Fig. 6A.

A more dramatic effect on the phase transition properties is observed for C4H9–DPPC systems, investigated over the concentration range of 0-10 mM (Figs. 5B and 6B), than for the shorter chain nicotinate, C2H5. At 10 mM C4H9, the phase transition temperature/melting temperature, Tm of the DPPC bilayers decreases to 33.3°C, ≈ 8K depression in Tm, relative to the 100 mM (33.3°C, 7K) required with C2H5. The width of the gel to fluid phase transition, ΔTr increases to 5°C with C4H9 concentration of 10 mM. To produce a 2.5 °C increase in gel to fluid phase transition width, ΔTr, 0.5 mM of C4H9 was needed compared with 10 mM for C2H5.

Lower nicotinate concentrations were sufficient to elicit perturbative effects on the gel to fluid phase transition as the chain length of the nicotinates was increased. The effect of C6H13 on the properties of the DPPC liposomes was examined over a range of (0 - 1mM) (Figs. 5C and 6C). There was a 9.2 °C reduction in the melting temperature of the pure DPPC liposomes in the presence of 1 mM C6H13. Conversely, the phase transition width, ΔTr, increased five-fold to 7 °C over the nicotinate concentration range of 0 to 1 mM C6H13. The shape of the anisotropy curve at 1 mM C6H13 was significantly altered relative to the pure DPPC curve as there is a much broader gel to fluid phase transition; the onset of the phase transition experienced a dramatic shift at this concentration. A concentration of 1μM of the longest chain nicotinate was enough to decrease Tm to 39.8 °C and increase the width by 2 °C.

The C8H17-DPPC system was investigated at 0 – 0.1 mM (Fig. 5D) and at highest concentration of C8H17, 0.1 mM, ΔTr increased by 7.6 °C and a Tm decreased to 34.8 °C (Fig. 6D). The anisotropy curves start to deviate from the pure DPPC curves in the presence of 50 μM C8H17, where the steepness of the gel to fluid phase transition is lost with increasing nicotinate concentration.

Partition Coefficients of Nicotinates

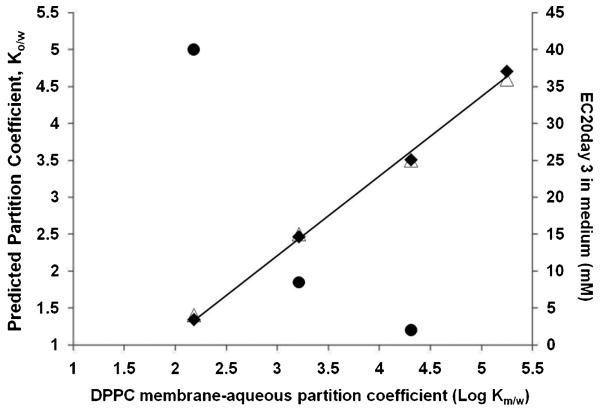

The partition coefficients of the nicotinates between the DPPC bilayers and the aqueous solution (Log Km/w) were determined by applying Eq. (2) and using the quantities estimated from the anisotropy measurements (Tm, ΔTm, Cs). Slopes of the depression of the melting temperature (ΔTm) as a function of bulk nicotinate concentration (graphs not provided) were used in Eq. (2) to calculate the membrane/water partition coefficients. For C2H5, the highest concentration of 200 mM was deleted from the plot of ΔTm against the concentration (not shown), as its presence resulted in a significant deviation from linear trend line (R2 = 0.99 was reduced to 0.95 with inclusion of 200 mM). The following partition coefficients were measured: C2H5 (log Km/w= 2.18), C4H9 (log Km/w = 3.21), C6H13 (log Km/w = 4.31) and C8H17 (log Km/w= 5.25). Figure 7 provides a plot of the experimental membrane/aqueous partition values relative to their octanol/water partition values, as available in literature[11, 32] and previously determined cytotoxicity levels [11]. Cytotoxicity levels are expressed as EC20 values in Figure 7, which represent the nicotinate concentration that generated 20% inhibitory effect on cellular activity. As with the Km/w, the octanol/water partition values(Log Ko/w) for C2H5 to C8H17 span several orders of magnitude as determined by predictive modeling (log Kp = 1.4 – 4.6)[11] and experimentally (log Ko/w = 1.34 – 4.71)[32]. Also, the trend in Fig. 7 shows a nonlinear increase in cytotoxicity with increased membrane partitioning. The shortest nicotinate, C2H5 expresses the least cytotoxic effect in in vitro studies while C6H13, displayed the highest cytotoxicity (C8H17 cytotoxicity not provided).

Figure 7.

Correlation of experimental DPPC bilayer-aqueous partition coefficients with predicted Ko/w partitioning values [11] (Δ) and published octanol-water values [31] (◆). (●)Trend with cytotoxicity data [11].

Discussion

Liposome-water partition measurements provide a basis for interpretation of drug incorporation in membranes [33] and are also useful in assessment of bioaccumulation of environmental chemicals [34]. Calorimetric and fluorescence spectroscopy techniques provide complementary information on the interaction of perhydrocarbon nicotinates with model lipid bilayers. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) probes subtle changes in chain order, such as the pretransition, and affords thermal assessment of changes in lipid chain organization at high lipid concentrations without the use of an external agent. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements can also be used to examine the phase transition of the bilayer and membrane fluidity as a function of temperature by changes in rotational diffusion of an embedded probe, DPH. In DSC, concentrated lipid bilayers (450 mM) are examined using significant concentrations of solute in order to generate sufficient thermal response. In contrast, perturbations of the bilayer are assessed by fluorescence anisotropy using dilute systems of liposomes (0.1 mM) to prevent light scattering effects. The four select nicotinates, C2H5, C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17 are a subgroup of a homologous series of derivatized nicotinic acid esters which possess functional groups to facilitate solubility in a fluorocarbon medium for potential drug delivery through the pulmonary route. Physicochemical properties such as octanol-water, fluorocarbon-toluene, fluorocarbon-water partition coefficients and cytotoxicity levels, pertaining to their relevance in the uptake of the prodrugs through a cellular matrix have been previously determined in cell culture studies [11]. This study of the interaction of the perhydrocarbon nicotinates with model DPPC membrane bilayers provides for a fundamental interpretation of the mechanism and efficacy of the delivery of these prodrugs.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DSC is a well established technique utilized in the study of thermotropic phase behavior of lipid bilayers and used to interpret the nature of molecular interactions with lipid bilayers without the aid of any external agents. Changes in the main transition and pretransition as a function of nicotinate concentration (Figures 2 – 4) indicate the incorporation of the nicotinates into the bilayer and the subsequent effects on acyl chain organization or assembly. The DPPC pretransition is a quasi-phase transition that involves the temperature induced realignment of the acyl chains from tilted gel to a rippled gel conformation [35, 36]. Due to the differences in cross-sectional area of the DPPC head group and lipid chain, there is a tilt at the interfacial regions to accommodate van der Waals interactions within the lipid chains and maintain the repulsive interaction between the head groups [36]. The pretransition in pure DPPC lipid bilayers at 37.8 °C is distinguished from the main phase transition at 42.3 °C, which is concomitant with the melting of the lipid chains. All the nicotinates, which are surface active, possess the same pyridine head group so differences in perturbative effects of incorporation in the bilayer can be attributed to chain length. Also, the experiments were performed at close to neutral pH, which is greater than the pKa of the nicotinates, ensuring they are mostly in an unprotonated form [32, 37]. The same mole fractions of DPPC/nicotinate (X DPPC = 0.6 – 1.0) were used for all the perhydrocarbon mixtures. The trends in Figs. 2 – 4, clearly demonstrate the ability of all the nicotinates to partition into the DPPC bilayer and effect concentration-dependent alterations in membrane structure/organization as a result of this insertion. In addition, all the nicotinates are miscible with the DPPC lipid chains as all the partial phase diagrams in Fig. 3 demonstrate a continual decrease in the thermal properties (melting temperature, onset, offset and width of transitions) with increasing solute concentration. Substantial changes in pretransition, including its elimination at higher nicotinate concentrations, suggest significant perturbation of the lipid chain order with nicotinate incorporation.

The pretransition was eliminated at mole fractions of XDPPC < 0.8, 0.9, 0.95, 0.9, for C2H5, C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17, respectively. With the exception of C6H13 and C8H17, changes in the onset, melting temperature and offset of the pretransition are minimal at low concentrations (i.e. X ≥ 0.97) of the nicotinates. Above this concentration, the impact of solute incorporation of the shorter chain nicotinates (C2H5 and C4H9) on lipid organization is more apparent. Overall, C2H5 has the least disruptive effect on membrane organization; the solution concentrations required to elicit similar changes in the pretransition are higher for C2H5 than for the longer chain nicotinates.

The endothermic peak shape of the main phase transition of C2H5-DPPC mixtures is preserved even at the highest concentration of the nicotinate studies (XDPPC = 0.6), as depicted in Fig. 2A. Although there are no anomalies in peak shape, the main transition peak broadening at XDPPC = 0.8 suggests reduced cooperativity of the bilayer phase transition in the presence of the solubilized nicotinates. Bilayer cooperativity describes changes to the uniform lipid arrangement during the bilayer phase transition and is affected by incorporation of solutes. During the phase transition the sequenced rotation of the individual acyl chains of DPPC to avoid unfavorable end-chain intermolecular interactions registers as a sharp transition profile in DSC and fluorescence anisotropy measurements (see below), suggesting a highly cooperative event [36]. Hence, the substantial increase in transition width at XDPPC ≤ 0.8 for C2H5 (Fig. 4A) indicates that incorporation of the nicotinate into DPPC bilayers significantly reduces the structural organization of the lipid chains.

This effect is also evident in changes in pretransition width (Fig. 4A) which are minimal at XDPPC ≥ 0.97 but increases considerably above this concentration for C2H5, till elimination at XDPPC < 0.8. With increasing short chain nicotinate concentrations, an abrupt change in the pretransition properties and, as discussed above, concomitant changes in the main phase transition are observed (Figs. 3A and 3B). For C2H5, the main transition width, melting temperature and onset show appreciable decrease simultaneously with dramatic changes in pretransition at XDPPC < 0.97, until it is eliminated at XDPPC < 0.8.

In C4H9-DPPC mixtures, the pretransition and main transition properties show little variance above XDPPC≥ 0.9. However, an abrupt change in main transition properties is observed at XDPPC < 0.9, at the same concentration as the pretransition is eliminated. Below XDPPC = 0.9, the onset of the main phase transition decreases rapidly with increasing C4H9 concentration. While the effect on onset temperature was more pronounced for C4H9 than C2H5, both short chain nicotinates had the same effect on the offset of the main phase transition. This corresponds to a much greater increase in main transition width (Fig. 4B) for XDPPC < 0.9 for C4H9 than C2H5. The trends with the short chain nicotinates can be interpreted from their physicochemical properties. With relatively short chain lengths and hydrophilicities, C2H5 (log Ko/w = 1.4) and C4H9 (log Ko/w = 2.5) are expected to be solubilized in the polar interfacial regions of the DPPC bilayers, which is a preferred location for similar short chain molecules [38, 39]. The interfacial molecular area of DPPC is reported to be 49 Å2, which is almost twice the area of the unprotonated nicotinate head group (25.2 Å2) in monolayer studies (air-water interface) [37]. Xiang and Anderson's [38] molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of DPPC liposomes suggest the bilayer can be stratified into regions with the headgroup area being the least dense with the highest hydration i.e. free volume. Hence, the free volume created by the mismatch of DPPC headgroup and lipid chains should facilitate solubilization of relatively hydrophilic short chain nicotinates (C2H5 and C4H9) with even distribution at low concentrations. Due to their small volumes, the solubilization of the short chain nicotinates in dilute systems should cause minimal perturbation to the head-group/chain tilt alignment. However with increasing concentration, the insertion of nicotinates in this region results in reorientation of the lipid chains, affects the headgroup/chain tilt and increases trans-gauche conformation of the lipid chains. These changes are consistent with distribution of the nicotinates to the acyl chain regions of the bilayer following saturation of the interfacial region with increasing nicotinate concentration. The resulting entropically unfavorable changes to the inner bilayer region or creation of the free volume would require adaptation of the bilayer matrix to accommodate solute incorporation and reduced free volume.

The perturbative effects on the bilayer are further enhanced with the more hydrophobic, longer chain nicotinates, C6H13 (Log Ko/w = 3.5) and C8H17 (Log Ko/w = 4.71), where possibly their longer chain lengths are able to penetrate the acyl region of the bilayers, with the nicotinate headgroup located close to the DPPC headgroup region. The reduction of pretransition properties is slightly more pronounced for C6H13 and C8H17 at lower concentrations (XDPPC ≥ 0.95) than for the shorter chained nicotinates in this series. The disappearance of the pretransition peaks below these concentrations is marked by more exaggerated decrease in main transition onset and melting temperature (Figs. 4C and D). The sigmoidal shape of the phase transition width for C6H13 suggests saturation of the bilayer at XDPPC = 0.7 while C8H17 continues to reduce the cooperativity till the highest concentration of nicotinate measured, XDPPC = 0.6 (Fig. 4B). Favorable van der Waals interactions between the nicotinate alkyl chains and lipid chains are expected to promote partitioning of the longer chain nicotinates (C6H13 and C8H17) into the bilayer, with the pyridine head group positioned close to the interfacial region. As both DPPC and nicotinates possess larger cross-sectional headgroup areas than tail group areas (i.e., increased mismatch), the orientation or position of the latter has been suggested to adopt a similar tilt to that of DPPC for longer chained nicotinates (C15H31 – C18H37) [37]. Similarly, the alkyl chains in C6H13 and C8H17 are expected to be aligned with the acyl chains of DPPC.

Complex phase behavior, characterized by asymmetrical broad peaks of the main phase transition, is observed for all nicotinates at high concentrations, with the exception of C2H5. The shoulders observed in the main transition endotherms at XDPPC = 0.6 (C4H9: 24.1 and 32.5 °C; for, C6H13: 18 °C for and C8H17: 30 °C) are indicative of heterogeneous lipid assemblies. As XDPPC decreases and the bilayer is increasingly enriched with nicotinate, the peaks might represent localized nicotinate-rich domains of a heterogeneous bilayer. The peaks appear at lower temperatures than the DPPC melting temperature and may represent melting phenomena in the pure nicotinates. In a previous study of long chain nicotinates (C15 – C18), secondary peaks at temperatures close to the melting temperatures of the pure nicotinates were distinctly visible [37]. These long chain nicotinates possessed melting temperatures that varied from ≈ 42 – 56 °C, with values similar or greater than that of DPPC (42 °C). Future knowledge of the melting temperatures of our series of nicotinates in this study would help elucidate the nature of the secondary peaks observed.

Fluorescence Anisotropy and Partition Coefficients

The fluorescence anisotropy of the DPH fluorophore is a measure of the local microviscosity of the central regions of the bilayer, where the probe is aligned in parallel with the acyl chains when the bilayer is in a gel state [40]. In the gel phase, the lipid chains are tightly packed and the DPH probe intercalated between the chains experiences little rotational motion. As temperature increases or chain organization is compromised due to solute incorporation, the bilayer fluidizes and the rotational motion increases. The anisotropy value experiences a decrease in going from a gel to a fluid phase bilayer, and can be used to determine the phase transition temperature and phase width.

The ability of the nicotinate to lower the melting temperature and increase the width of the phase transition is a strong function of the nicotinate chain length (Fig. 5). In agreement with the DSC results, the C2H5 has the least perturbing effect on the phase transition properties and the phase transition has distinguishable features even in the presence of 200 mM C2H5, the highest concentration of nicotinate investigated. The sharp transition profile of gel to fluid phase of DPPC is preserved for C2H5 concentrations, 0 – 10 mM (Fig. 6A). At concentrations ≥ 50 mM, there is considerable increase in the phase transition width, with a concomitant reduction in the melting temperature. The shape of the anisotropy curve at 200 mM C2H5 (Fig. 5A) suggests extensive fluidization of the bilayer due to solubilization of C2H5; the melting temperature is considerably depressed to a value of 32 °C. The phase transition width as a function of C2H5 (Fig. 6A) concentration is consistent with saturation of the DPPC bilayer at approximately 100 mM C2H5. Above this concentration, the phase transition width remains constant, although there is a further reduction in melting temperature. Analogous to DSC analysis, broadening of the phase transition width or increase in ΔTr is a measure of the cooperativity of the lipid chains in the bilayers. At low concentrations (0 – 10 mM), the solubilization of C2H5 has minimal effect on bilayer cooperativity. As the concentration is increased, solute incorporation into the bilayer results in reduction of lipid chain order and cooperativity with increased fluidization of the bilayer.

Significant changes in the melting temperatures and width of the transition occur at 1 mM, 0.1 mM and 10 μM for C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17, respectively. (Figs. 6B - D). The concentrations required to elicit the same decrease in the DPPC melting temperature span three orders of magnitude from the shortest to the longest alkyl chain for the nicotinates. For example, the nicotinate concentrations required to achieve a decrease in the melting temperature of 3.5 °C (or reduction of DPPC Tm to 37.8 °C), is estimated as 36 mM (C2H5), 3.6 mM (C4H9), 0.25 mM (C6H13) and 32.5μM (C8H17). These values were extrapolated from the near linear functions of melting temperature, Tm, with nicotinate concentration (Fig. 6). In contrast, ΔTr as a function of nicotinate concentration displays strong deviations from linearity. In a study of a series of alcohols, from butanol to octanol, comparable effects on phase transition temperature and phase transition width were reported [41].

The partitioning of the nicotinate solutes in the bilayer relative to the aqueous phase varies by orders of magnitude, with an increasing affinity for the bilayer with increasing chain length. The partition coefficients, as determined from the fluorescence anisotropy experiments, vary from log Kp of 2.18 (C2H5) to 5.25 (C8H17). The order of membrane partitioning is in direct proportion to octanol/water partitioning (Fig. 7), which suggests that the partitioning into the bilayer correlates with hydrophobicity/lipophilicity of the nicotinates, which increases from C2H5 to C8H17. Similar trends have been reported for series of halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons [42], where the log Ko/w was in linear proportion to log Km/w in the range of 1 – 5.5.

Partition coefficients for the nicotinates, as previously determined in our laboratory [11] showed increased propensity for the organic phase (toluene) in immiscible perfluoromethylcyclohexane/toluene system, with nicotinate hydrocarbon chain length. The partition coefficients, which range from log KPMCH/Toluene = -2.22 (C2H5) to -2.92 (C8H17), indicate reduced fluorophilicity with chain length. In contrast, fluorocarbon (PFOB)/water partition coefficients increased from log Kp = -0.16 (C2H5) to 1.24 (C6H13), indicating reduced preference for the aqueous phase with nicotinate chain length. However, these changes in partition coefficient are minimal relative to the membrane/water, log Km/w= 2.18 (C2H5) – 5.25 (C8H17); with the orders of magnitude variance mirrored by octanol/water partitioning (log Ko/w = 1.4–4.7) [32].

The trend in partitioning and the consequent perturbing effects on the liposome bilayer arrangement with nicotinate chain length is also reflected in their cytotoxic effect on human lung cells [11], as shown in Figure 7. The concentrations of nicotinate required to generate a marked cytotoxic effect when delivered from buffered medium to the cells was in inverse relation to the chain lengths of the nicotinates (C2H5 – C6H13) and are in proportion to the bilayer partition coefficients, as determined in this study. With the cytotoxicity mirroring the partition trends in this study, this confirms the ability of this subgroup of perhydrocarbon nicotinates to act as effective prodrug delivery agents.

Conclusions

The perhydrocarbon nicotinates investigated in this study (C2H5, C4H9, C6H13 and C8H17) all partition into DPPC bilayers, although their affinity for the bilayer and the effect of their incorporation in the bilayer is a function of the length of their alkyl chain length. The combination of DSC and fluorescence anisotropy techniques allows for a better interpretation of the interaction of the nicotinates with DPPC bilayers, which has significance for pulmonary targeted drug delivery. The quantitative results of DSC and DPH fluorescence anisotropy are largely in agreement, in that bilayer disruption increases with the chain length of the nicotinates. The apparent partition coefficients of the solutes in the bilayer span four orders of magnitude, from log Km/w = 2.18 to 5.25. The direct correlation of membrane partition coefficients with log Ko/w, is consistent with previous findings that hydrophobicity is the primary driving force in lipid bilayer partitioning. The shortest chain nicotinate, C2H5, has the lowest log Km/w and the least disruptive effect on the bilayer in the series. This supports in vitro cytotoxicity studies which show that C2H5 has the least inhibitory effect on cellular function [11]. Furthermore, DSC suggests that all nicotinates are solubilized in close proximity to the DPPC headgroup region at low concentrations, which affects the pretransition. At higher concentrations, more disruptive effects of the nicotinates on the lipid acyl packing are evident from the reduced cooperativity of the main phase transition. Complex phase behavior with C6H13 and C8H17 suggests considerable structural disorganization with incorporation of these longer chained nicotinates at high concentrations. Effective prodrug delivery through the pulmonary route requires the balance of bioavailability and minimized cytotoxicity. Insight into the interactions and uptake of solutes in a cellular matrix, as provided by the partitioning behavior in model membranes, aids the systematic design of prodrugs.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH, grants ES07380 and ES012475.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rongvaux A, Andris F, Van Gool F, Leo O. Bioessays. 2003;25:683. doi: 10.1002/bies.10297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Q, Giri DM, Hyde M, Nakashima JM, Javadi I. J Biochem Toxicol. 1990;5:13. doi: 10.1002/jbt.2570050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai A, Yasui S, Ozawa Y, Uno H, Konno K. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altschul R, Hoffer A, Stephen JD. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1955;54:558. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(55)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamanna VS, Kashyab ML. Curr Atheroscl Rep. 2000;2:36. doi: 10.1007/s11883-000-0093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachter M. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:415. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-5685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vogt A, Kassner H, Hostalek U, Steinhagen-Thiessen E. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:467. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murrray MF. Med Hypotheses. 1999;53:375. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1999.0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson EL, Shieh WM, Huang AC. Mol Cell BioChem. 1999;193:69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyton JR, Bays HE. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:22C. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehmler HJ, Xu L, Vyas SM, Ojogun VA, Knutson BL, Ludewig G. Int J Pharm. 2008;353:35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linderoth L, Peters GH, Madsen R, Andresen TL. Angew Chem. 2009;121:1855. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiss JG, Krafft MP. Biomaterials. 1998;19:1529. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krafft MP, Reiss JG. Biochimie. 1998;80:489. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)80016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehmler HJ, Bummer PM, Jay M. Chemtech. 1999;29:7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmler HJ. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2007;4:247. doi: 10.1517/17425247.4.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu CH, Jay M, Bummer PM, Lehmler HJ. Pharm Res. 2003;20:918. doi: 10.1023/a:1023899505837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rocaboy C, Rutherford D, Bennett BL, Gladysz JA. J Phys Org Chem. 2000;13:596. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin R, Barton P, Davis A, Fessey R, Wenlock M. Pharm Res. 2005;22:1649. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-6336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon JH, Liljestrand HM, Katz LE. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25:1984. doi: 10.1897/05-550r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aguilar LF, Sotomayor CP, Lissi EA. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem Eng Aspects. 1996;108:287. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie W, Kania-Korwel I, Bummer PM, Lehmler HJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1299. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmler HJ, Xie W, Bothn GD, Bummer PM, Knutson BL. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2006;51:25. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morishita S, Saito T, Hirai Y, Shoji M, Mishima Y, Kawakami M. J Med Chem. 1988;31:1205. doi: 10.1021/jm00401a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ladbrooke BD, Chapman D. Chem Phys Lipids. 1969;3:304. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(69)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bangham AD, Standish MM, Watkins JC. J Mol Biol. 1965;13:238. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olson F, Hunt CA, Szoka FC, Vail WJ, Papahadjopoulos D. Biochim Biophys Acta: Biomembranes. 1979;557:9. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bothun GD, Knutson BL, Strobel HJ, Nokes SE. Langmuir. 2004;21:530. doi: 10.1021/la0496542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lackowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Kluwer Academic; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inoue T, Miyakawa K, Shimozawa R. Chem Phys Lipids. 1986;42:261. doi: 10.1016/0009-3084(86)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koynova R, Caffrey M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376:9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le VH, Lippold BC. Int J Pharm. 1998;163:11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neunert G, Polewski P, Markiewicz M, Walejko P, Witkowski S, Polewski K. Biophys Chem. 2010;146:92. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Der Heijden SA, Jonker MTO. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:8854. doi: 10.1021/es902278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntosh TJ. Biophys J. 1980;29:237. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagle JF. Ann Rev Phys Chem. 1980;31:157. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lehmler HJ, Fortis-Santiago A, Nauduri D, Bummer PM. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:535. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400406-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiang TX, Anderson BD. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:1357. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Young LR, Dill KA. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5281. doi: 10.1021/bi00414a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sklar LA, Hudson BS, Peterson M, Diamond J. Biochemistry. 1977;16:813. doi: 10.1021/bi00624a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee AG. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2448. doi: 10.1021/bi00656a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gobas FAPC, Mackay D, Shiu WY, Lahittete JM, Garofalo G. J Pharm Sci. 1987;77:265. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600770317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]