CONSPECTUS

Proteins are Nature’s premier building blocks for constructing sophisticated nanoscale architectures that carry out complex tasks and chemical transformations. It is estimated that 70–80% of all proteins are permanently oligomeric, that is, they are composed of multiple proteins that are held together in precise spatial organization through non-covalent interactions. While it is of great fundamental interest to understand the physicochemical basis of protein self-assembly, the mastery of protein-protein interactions (PPIs) would also allow access to novel biomaterials using Nature’s favorite and most versatile building block. With this possibility in mind, we have developed a new approach, Metal Directed Protein Self-Assembly (MDPSA), which utilizes the strength, directionality and selectivity of metal-ligand interactions to control PPIs.

At its core, MDPSA is inspired by supramolecular coordination chemistry which exploits metal coordination for the self-assembly of small molecules into discrete, more-or-less predictable higher-order structures. Proteins, however, are not exactly small molecules or simple metal ligands: they feature extensive, heterogeneous surfaces that can interact with each other and with metal ions in unpredictable ways. We will start this Account by first describing the challenges of using entire proteins as molecular building blocks. This will be followed by our work on a model protein (cytochrome cb562) to both highlight and overcome those challenges toward establishing some ground rules for MDPSA.

Proteins are also Nature’s metal ligands of choice. In MDPSA, once metal ions guide proteins into forming large assemblies, they are by definition embedded within extensive interfaces formed between protein surfaces. These complex surfaces make an inorganic chemist’s life somewhat difficult, yet they also provide a wide platform to modulate the metal coordination environment through distant, non-covalent interactions – exactly as natural metalloproteins and enzymes do. We will describe our computational and experimental efforts on restructuring the non-covalent interaction network formed between proteins surrounding the interfacial metal centers. This approach of metal templating followed by the redesign of protein interfaces (Metal-Templated Interface Redesign, MeTIR) not only provides a route to engineer de novo PPIs and novel metal coordination environments, but also carries possible parallels to the evolution of metalloproteins.

Introduction

Proteins are the most versatile class of biological molecules thanks to the wide array of chemical functionalities provided by their 20 amino acid constituents. These functionalities enable the construction of sophisticated 3D structures, aid in catalytic reactions, and importantly for bioinorganic chemists, form an astonishing variety of coordination complexes. What makes proteins even more versatile is their ability to specifically recognize and bind other protein molecules. In fact, only a small fraction of proteins fulfill their physiological functions alone.

It is safe to say that protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are the chief contributors to cellular complexity. Transient PPIs are responsible for cellular dynamics, communication and transfer of chemical currency (e.g., electrons, phosphate groups), whereas permanent PPIs are central to the construction of cellular machinery. These key roles of PPIs have motivated intense efforts to elucidate their physicochemical basis,1 develop pharmaceutical agents that impede their formation,2 and engineer them de novo.3 Invariably, all these efforts are complicated by the fact that PPIs are composed of weak, noncovalent bonds distributed over large and sometimes flexible protein surfaces.2

To circumvent the challenge of ruling over numerous weak bonds, we envisioned that if protein surfaces are appropriately modified, PPIs could be controlled through metal coordination. Using metal coordination to guide PPIs offers several advantages. First, metal-ligand bonds are stronger than the non-covalent bonds that make up protein interfaces, obviating the need to engineer large surfaces to produce favorable protein-protein docking. Second, metal-ligand bonds are highly directional, thus the stereochemical preference and symmetry of metal coordination may be imposed onto PPIs. Third, metal-ligand bonds can be kinetically labile, allowing PPIs to proceed under thermodynamic control. Fourth, metal coordination can be formed or broken through pH changes or external ligands, rendering PPIs responsive to external stimuli. And fifth, metal ions bring along intrinsic reactivity (Lewis acidity, redox reactivity), which may be incorporated into protein interfaces.

All these advantages of metal coordination have been cleverly exploited in molecular self-assembly.4,5 Under the umbrella of supramolecular coordination chemistry and the burgeoning field of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), many groups have utilized metal coordination to organize small organic ligands into well-defined assemblies and multi-dimensional arrays that are finding applications in host-guest chemistry,6 sensing,7 storage/separation,8 catalysis.9 So, we asked whether the same could be done using individual proteins – Nature’s favorite and most versatile ligands – as building blocks.

Using metal coordination in biological self-assembly is of course nothing new; Nature does it all the time. A major fraction of known proteins contain metal ions as integral components required for proper folding,10 and more and more natural protein complexes with bridging metal ions are being discovered.11,12 Such biological systems have inspired the design of a diverse array of artificial metalloproteins.13 Impressively, some of such engineered metalloproteins manifest properties characteristic of highly-evolved natural systems, such as selectivity,14 redox tunability15 and open coordination sites that allow for reactivity.16 Inspired by such advances in both protein design and supramolecular coordination chemistry, our ultimate goal is to meld the principles and strengths of these two approaches 1) to build novel biological assemblies with predictable shapes and dimensions, and 2) to construct functional and tunable metal coordination sites within these assemblies.

Metal-Directed Protein Self Assembly

Challenges of MDPSA and cytochome cb562 as a model building block

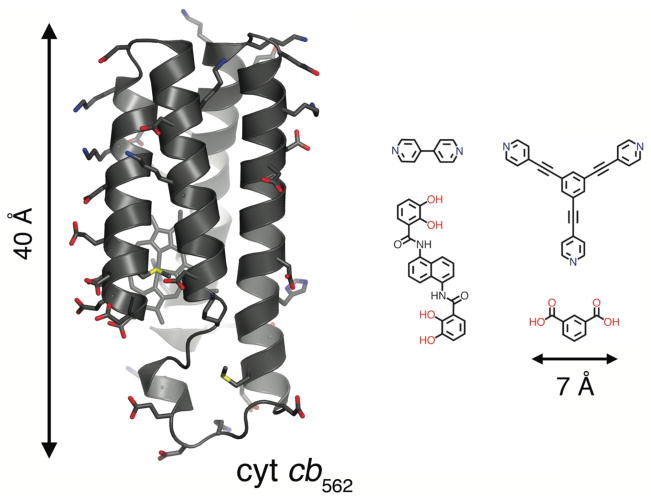

There are significant challenges in considering proteins as building blocks for metal-directed self-assembly. These challenges become immediately apparent upon comparing ligands typically used in supramolecular coordination chemistry with even a small protein like cytochrome cb562 (cyt cb562) employed in our studies (Fig. 1). The first hurdle is the selective localization of metal coordination. Whereas with a small organic ligand the metal binding mode is essentially predetermined, surfaces of water-soluble proteins are inundated with metal-coordinating side chains. This can lead to the simultaneous binding of multiple metal ions on the protein surface, and to the formation of heterogeneous mixtures of metal-crosslinked protein polymers. Not surprisingly, most soluble proteins precipitate in the presence of high concentrations of transition metals.

Figure 1.

Cyt cb562 and representative organic building blocks used for constructing supramolecular coordination complexes and MOFs. Surface residues with coordinating ability are shown as sticks.

The second hurdle stems from the large sizes of proteins. In most supramolecular coordination complexes and MOFs, the interactions between the ligands forming the backbone are so small as to be negligible. Only recently have there been examples where the effects of ligand-ligand interactions have been recognized and utilized in metal-directed self-assembly.17 In contrast, proteins are considerably larger molecules whose surfaces are bound to come into extensive contact upon metal crosslinking. To compound the problem, the topography and composition of protein surfaces are highly irregular, making the outcome of protein self-assembly even harder to predict.

In order to circumvent some of these challenges, we decided to simplify our task a bit by choosing cyt cb562 as a model protein building block. This choice was made for several reasons. Cyt cb562 is a variant of the four-helix bundle hemeprotein cyt b562 that contains genetically engineered linkages between the heme and the protein backbone.18 These covalent bonds render cyt cb562 significantly more stable towards unfolding and thereby more resistant to structural perturbations as its surface is modified for metal binding. Much like an organic building block, cyt cb562 is readily synthesized – by bacteria that is – and isolated in large quantities. It has a rigid, cylindrical shape, which is not only ideal as a building block for large assemblies, but also makes such assemblies – in our experience – more amenable to crystallization and structural analysis. It has a uniform, all-α-helical topology, which, as discussed below, provides a nice handle for engineering metal coordination sites onto all facets of its surface. Finally, cyt cb562 is physiollogically monomeric and remains that way even at millimolar concentrations, meaning that its surface does not carry any bias towards oligomerization. This is crucial if metal coordination is intended to be the primary driving force for self-assembly.

Where to start with MDPSA?

Even when proteins possess a simple shape and a uniform topology like cyt cb562, it can be challenging to visualize protein-protein docking geometries that would be amenable to metal crosslinking; surface composition and topography of proteins are still highly heterogeneous. For inspiration, we turned to crystal packing interactions (CPIs), which provide a source of feasible protein-protein docking geometries. A given CPI typically is not extensive (<1000 Å2) and only stable in combination with other CPIs under crystallization conditions, yet it provides a metastable arrangement of proteins in which there are no steric clashes between them.19 Importantly, CPIs may contain 2-fold or higher symmetry, which minimizes the number of metal coordination motifs that need to be engineered onto protein surfaces for MDPSA, and provides a starting point to design high-order protein oligomers and superstructures.

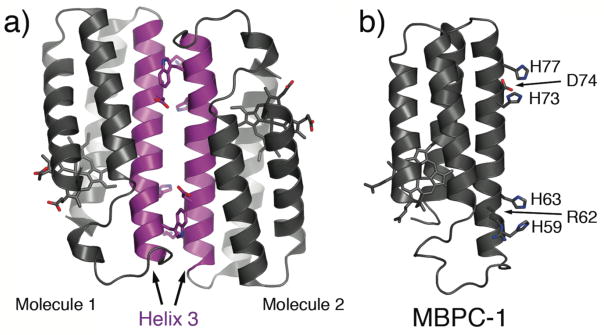

An examination of CPIs in cyt cb562 crystals reveals that each monomer is paired in an antiparallel fashion with another monomer along their 3rd helices (Fig. 2a).18 This relatively large (775 Å2), C2 symmetrical interface is clearly non-physiological, since cyt cb562 is monomeric in solution at concentrations used for crystallization (2–5 mM). At the same time, this close-packed arrangement of monomers shows us a route for the self-assembly of cyt cb562, whereby two metal binding motifs can be incorporated near each end of Helix3 for metal-mediated crosslinking.

Figure 2.

(a) Antiparallel arrangement of cyt cb562 molecules in the crystal lattice along their Helix3’s (magenta). (b) Model of MBPC-1, where key residues involved in metal binding and secondary interactions are depicted as sticks.

To address the challenge of selective metal localization, we exploit the simple principle of the chelate effect. All metal-coordinating groups on a protein’s surface are either formally or effectively monodentate, and considered as weak ligands at neutral pH except His and Cys. Therefore, if a bi- or tridentate metal chelating motif can be installed on a protein surface, it should theoretically outcompete other functionalities for metal binding while leaving coordination sites free to accommodate other protein monomers. The i, i+4 bis-His motif on α-helices, in particular, is a high-affinity bidentate motif frequently utilized for the assembly of natural and engineered metalloproteins.20 We thus constructed a model system (MBPC-1), which is a cyt cb562 variant containing two such bis-His motifs (His59/His63 and His73/His77) near the ends of Helix3 (Fig. 2b).21 We describe below our initial studies with MBPC-1 – and its derivatives – that laid the foundation for MDPSA, revealed the challenges as well as unforeseen research avenues involved in this approach and provided a springboard for future studies.

Zn(II)-directed self assembly of MBPC-1

A tenet of self-assembly is reversibility, which allows molecular components to avoid forming kinetically-trapped complexes on their way to the thermodynamically favored product(s). With this in mind, we first examined the self-assembly properties of MBPC-1 in the presence of Ni(II), Cu(II) and Zn(II), which are all exchange labile and form stable complexes with the i, i+4 bis-His motif.22 Importantly, each of these metal ions has a distinct stereochemical preference, providing an opportunity to investigate the effect of metal coordination geometry on supramolecular assembly.

Our first revealing observations come from experiments with Zn. Upon addition of an excess of Zn, MBPC-1 promptly precipitates out of solution. The precipitation is reversible upon addition of chelators like EDTA or acidifying the solution (pH ≤ 5), suggesting that His-Zn interactions are partaking in the formation of heterogeneous aggregates. It is likely that in the presence of excess Zn, both bis-His clamps as well as other sites on the protein surface are charged with metal, resulting in a mixture of insoluble metal-crosslinked protein polymers.

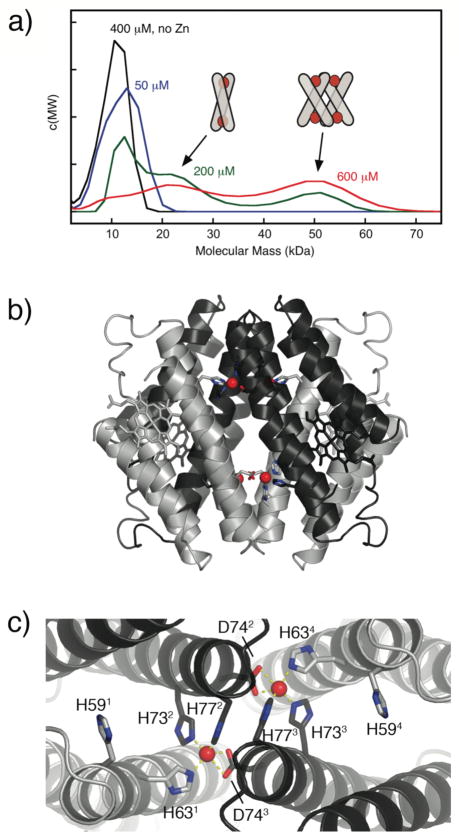

To probe the formation of any discrete supramolecular assemblies at equimolar or lower Zn/MBPC-1 ratios, we studied the hydrodynamic properties of the resulting solutions via sedimentation velocity (SV). SV measurements show that MBPC-1 is entirely monomeric at low protein and Zn concentrations, but gives way first to a dimeric and then to a larger species at increasing concentrations (Fig. 3a).21 We were able to structurally characterize the latter species which emerged as a tetrameric assembly (Zn4:MBPC-14) with a unique D2-symmetrical supramolecular topology stabilized by four Zn(II) ions (Fig. 3b).21 Each of these Zn ions are found in an identical, tetrahedral coordination environment completed by a 73/77 bis-His clamp from one protein monomer, His63 from a second, and unexpectedly, Asp74 from a third instead of His59 (Fig. 3c). This unforeseen crosslinking of three monomers by each Zn gives rise to the dihedral symmetry of the assembly, which is best described as two V-shaped MBPC-1 pairs wedged into one another.

Figure 3.

(a) Molecular mass distributions for MBPC-1 and equimolar Zn(II) (except where noted) determined by SV measurements, and proposed Zn-induced supramolecular geometries corresponding to dimeric and tetrameric species. (b) Sideview of Zn4:MBPC-14. (c) Topview of Zn4:MBPC-14, highlighting the coordination environment of interfacial Zn ions.

This structure, along with the SV results, implies the following: 1) Zn-mediated assembly of MBPC-1 indeed proceeds under thermodynamic control as evidenced by the formation of discrete species (monomer, dimer, tetramer) that appear to be exchanging. 2) In the absence of any specific PPIs, protein self-assembly is governed by metal coordination: the proteins adopt a supramolecular arrangement so as to saturate the metal coordination sphere and fulfill the stereochemical preference of the metal ion. Based on this argument, we propose that the dimeric species favored at intermediate Zn and MBPC-1 concentrations features a crisscrossed alignment of MBPC-1 monomers, in which two Zn ions are coordinated by both bis-His clamps in a tetrahedral arrangement (Fig. 3a inset). At higher concentrations, the monomers rearrange into the crystallographically characterized Zn4:MBPC-14, whereby the entropic cost of forming this eight-component assembly is overcome by the enthalpic gain due to the coordination of four Zn ions, likely with positive cooperativity.

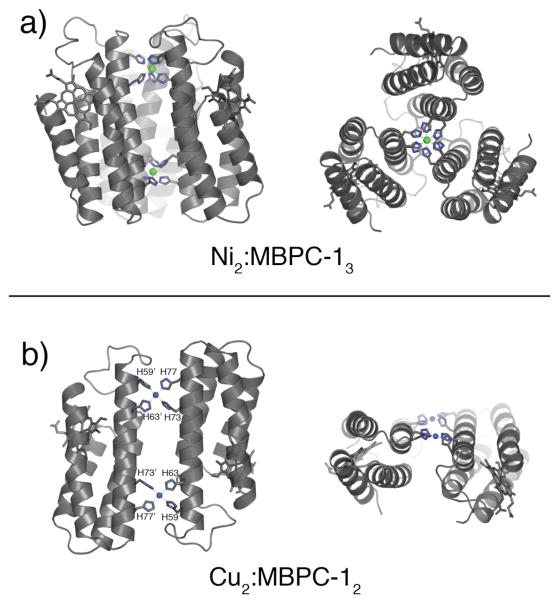

Inner sphere coordination geometry governs oligomerization symmetry

If the extent and symmetry of MBPC-1 self-assembly is governed by metal coordination as suggested above, then metal ions with non-tetrahedral preferences should lead to the formation of alternate supramolecular architectures. Crystal structures of Cu(II) and Ni(II) complexes of MBPC-1 show that this is indeed the case (Fig. 4).23 Cu(II) induces an antiparallel C2-symmetric dimer (Cu2:MBPC-12), which features two Cu centers with a square planar coordination sphere formed by two equatorial bis-His clamps (59/63 and 73/77). Ni(II) coordination, on the other hand, accommodates three bis-His clamps in an octahedral geometry, yielding a parallel C3-symmetric trimer (Ni2:MBPC-13) crosslinked by two Ni(II) ions.

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of (a) Ni2:MBPC-13 and (b) Cu2:MBPC-12 viewed from the side and the top.

The distinct oligomerization geometries obtained with Cu, Ni, and Zn firmly indicate that the supramolecular arrangement of MPBC-1 can be controlled by metal coordination geometry. This finding demonstrates how a basic inorganic principle can be applied to a yet-to-be-solved biochemical problem, namely the engineering of a protein surface that can assume multiple oligomeric states under the control of a simple external stimulus. Moreover, the facile access to different symmetries through metal coordination without the need to engineer large surfaces may open up the path for constructing multidimensional protein architectures, which require building blocks that simultaneously utilize a combination of these symmetry elements.

Bringing non-natural ligands into the mix

Following the footsteps of others,13 we imagined that the structural and functional scope of MDPSA could be significantly broadened if synthetic metal ligands are interfaced with proteins. From a structural viewpoint, a multidentate ligand incorporated into a protein’s surface via a single point attachment can offer more structural flexibility than, for instance, a bis-His motif. At the same time, the large number of ligands available in the synthetic toolbox would offer great diversity in terms of tuning metal reactivity.

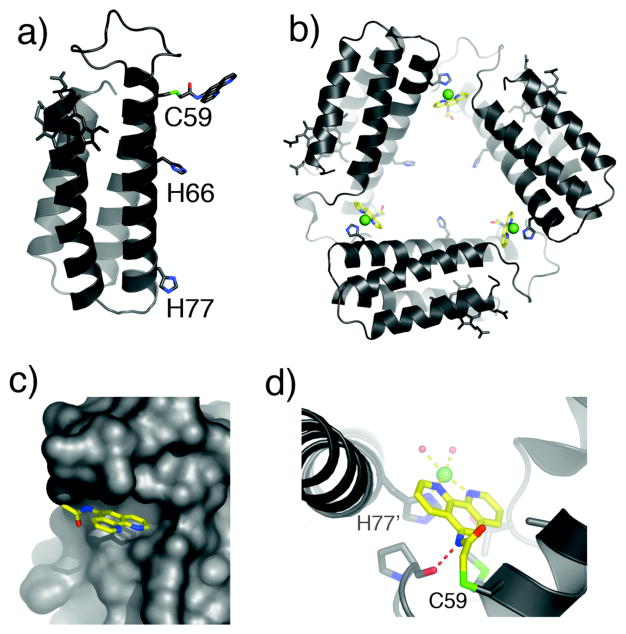

In a recent proof-of-principle study, we employed the Cys-specific iodoacetamide derivative of phenanthroline (IA-Phen) to construct MBP-Phen1, which contains a single Phen group covalently-bound to Cys59 near the N-terminus of Helix3, and His77 incorporated at the opposite end (Fig. 5a). The crystal structure of the Ni(II) adduct of MBP-Phen1 reveals a unique triangular assembly, Ni3:MBP-Phen13, whose vertices are formed by a Ni ion coordinated to PhenC59 from one protein monomer and His77 from another (Fig. 5b).24 The flat shape and dimensions of Ni3:MBP-Phen13 are reminiscent of the 3-fold symmetrical components of biological cages such as the 432-octahedral ferritin shell and the 532-icosahedral viral capsids.

Figure 5.

(a) Model for MBP-Phen1, highlighting potential metal binding sites on Helix3. (b) Crystal structure of Ni3:MBP-Phen13. (c) Surface representation of Ni3:MBP-Phen13, showing the burial of the Phen group under the 50’s loop. (d) Ni coordination environment in Ni3:MBP-Phen13. The H-bond between the P53 carbonyl and the PhenC59 amide nitrogen is indicated with a red dashed line.

The phenanthroline group, instead of extending into the solvent, is located in a small hydrophobic crevice underneath the 50’s loop (Fig. 5c). This placement of Phen is the key to the open Ni3:MBP-Phen13 architecture, as it protects the Ni ion from coordination by a second Phen group, resulting in an unsaturated, roughly square-pyramidal Ni coordination geometry (Fig. 5d). This demonstrates that protein surface features can be used as steric encumbrance to yield coordinatively unsaturated metal binding sites. IR measurements on Ni3:MBP-Phen13 crystals indicate that the interfacial Ni centers can indeed accommodate extrinsic ligands like cyanate.24

The second challenge of MDPSA: the influence of non-covalent PPIs

With the dominant role of metal coordination established, we next asked if the non-covalent interactions formed between protein monomers had any effect on protein self-assembly. Zn4:MBPC-14, in particular, features a very extensive set of close protein-protein contacts (~5000 Å2). To quickly probe if these contacts have a sizeable collective influence on the thermodynamics of self-assembly without introducing extensive surface mutations, we made a small perturbation in the metal coordination instead.

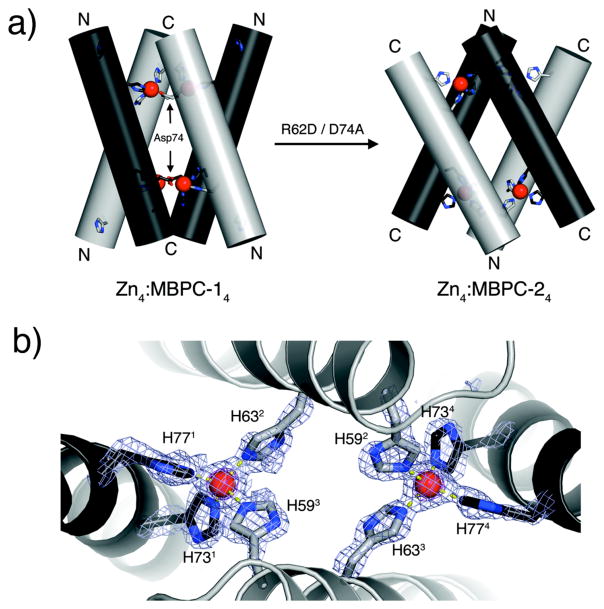

As discussed above, each Zn in Zn4:MBPC-14 is coordinated by an Asp74 located within the 73/77 bis-His clamp in the i+1 position. Ligation by Asp74’s, instead of the originally expected His59’s, is key to the supramolecular architecture of Zn4:MBPC-14, in that they crosslink the MBPC-1 monomers at the Helix3 C-termini to yield the V-shaped dimers. We reasoned that if non-covalent interactions between protein monomers had negligible effect and metal coordination was the sole determinant of protein self-assembly, then the whole oligomeric assembly could be “inverted” simply by moving the coordinating Asp residue from within the C-terminal 73/77 bis-His clamp into the N-terminal 59/63 bis-His clamp motif at the i+3 position. To this end, we engineered MBPC-2, the D74A/R62D variant of MBPC-1 (Fig. 2b), and determined its Zn-induced self-assembly properties.25

As planned, MBPC-2 forms tetramers upon binding one equivalent of Zn according to SV measurements, which indicate that the stability of Zn4:MBPC-24 is significantly elevated compared to Zn4:MBPC-14. The crystal structure of Zn4:MBPC-24 reveals a D2-symmetrical architecture, which indeed is the “inverse” of Zn4:MBPC-14 (Fig. 6a).25 Whereas the V shapes are joined at the Helix3 C-termini in the latter, they are crosslinked at the N-termini in the former. Unexpectedly, however, the newly engineered Asp62 is not involved in Zn binding. Instead, each Zn ion in the assembly is ligated by the 73/77 bis-His motif from one monomer, His59 from a second, and His63 from a third, again yielding a tetrahedral Zn coordination geometry. In this arrangement, the V’s are stabilized by His59 and His63 coordination – instead of the planned Asp62 and His63 coordination – from two monomers, which spread apart to bind two Zn ions, joining the Helix3 N-termini (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6.

(a) Cylindrical representations of Zn4:MBPC-14 and Zn4:MBPC-24 Helix3’s and sidechains involved in Zn coordination viewed from the side. N- and C-termini of Helix3’s in each assembly are labeled accordingly. (b) Closeup of the interfacial Zn coordination environment.

Similarities between Zn4:MBPC-14 and Zn4:MBPC-24 structures suggest convergence in their mechanisms of self-assembly, i.e., tetrahedral Zn coordination enforces D2 supramolecular symmetry. Yet, there are also some important distinctions between the two. Why does MBPC-2 not oligomerize through the available His3-Asp1 Zn-coordination motif? Conversely, why does MBPC-1 not self-assemble through the same His4 motif as MBPC-2? And why is Zn4:MBPC-24 more stable than Zn4:MBPC-14 despite the fact that both assemblies are held together by four Zn ions in unstrained, tetrahedral coordination geometries? The answer clearly lies in the non-covalent interactions found in protein interfaces.

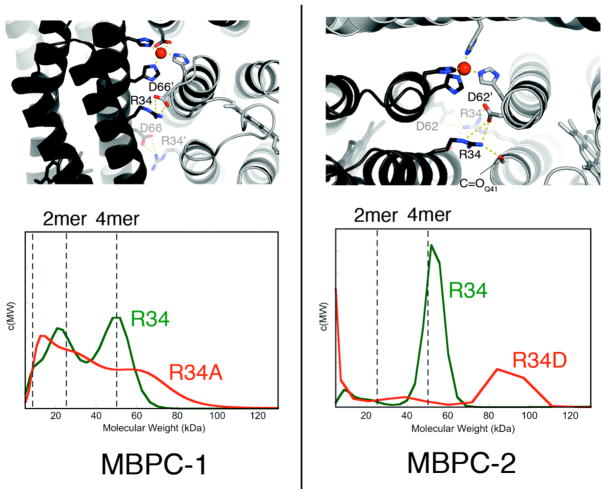

Zn4:MBPC-14 and Zn4:MBPC-24 both possess interfaces that possess only about one third of the average H-bond density of a natural protein-protein interface26 and no obvious hydrophobic interactions that would be expected to drive protein oligomerization. The majority of the H-bonding interactions involve two pairs of residues that form salt bridges: Arg34-Asp62 in Zn4:MBPC-24, and Arg34-Asp66 in Zn4:MBPC-14 (Fig. 7a). Significantly, when these interactions are abolished through the Arg34Asp (MBPC-2) and Arg34Ala (MBPC-1) mutations, the tetrameric assemblies are replaced by heterogeneous ensembles that contain higher order aggregates (Fig. 7b).25 Apparently, secondary interactions can have a major influence on the outcome of MDPSA.

Figure 7.

(top) Interfacial H-bonding interactions in Zn4:MBPC-14 and Zn4:MBPC-24. (bottom) Molecular weight distributions of MBPC-1 and MBPC-2 species as determined by SV measurements. All samples contain 600 μM protein and 600 μM Zn, with the exception of R34A-MBPC-1, which contains 300 μM Zn.

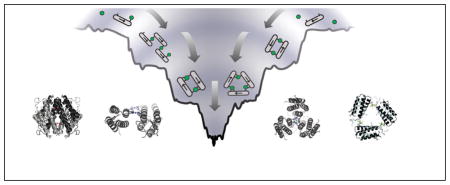

Combining metal coordination and non-covalent interactions: A terraced energy landscape for MDPSA

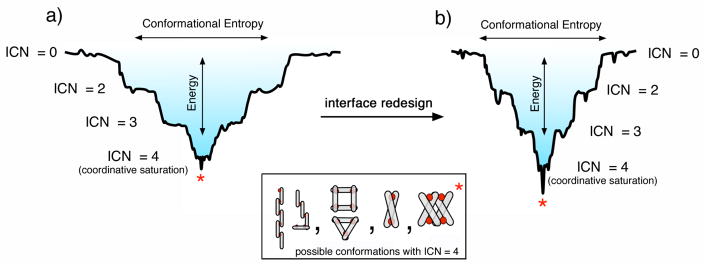

MDPSA – or protein self-assembly in general – is analogous to protein folding in terms of the physical processes involved: loss of conformational entropy due to the formation of ordered structures with a concomitant decrease in enthalpy due to bond formation. Like protein folding,27 the energy landscape of MDPSA can also be described in terms of a funnel that qualitatively incorporates both the entropic and enthalpic contributions (Fig. 8). One important distinction between protein folding and MDPSA is that the latter is dominated by the enthalpic term due to the formation of strong metal-protein bonds – especially in the absence of many specific non-covalent interactions between protein monomers (Fig. 8a). This leads to a “terraced” landscape for MDPSA, where each terrace is defined by the number of bonds formed between protein monomers and interfacial metal ions (interprotein coordination number, ICN).

Figure 8.

Terraced energy landscapes for MDPSA in the absence (a) or presence (b) of specific protein-protein interactions. The funnels shown apply to the Zn-driven oligomerization of MBPC-1 (a) and RIDC-1 (b). ICN denotes “interprotein coordination number” for interfacial metal ions. The asterisk denotes the preferred conformation, which is a D2-symmetrical assembly shown in the Inset.

Given the large number of metal binding functionalities on the protein surface, there are many different protein alignments that can satisfy the same ICN. The ruggedness of the terraces, then, are defined by the non-covalent interactions formed between the protein monomers. As more interfacial protein-metal bonds are formed, the terraces become progressively narrower, ultimately leading to the most stable conformation(s) with saturated metal coordination. As our results indicate, even the lowest basin of the MDPSA funnel is somewhat wide and smooth. In the case of Zn and MBPC-1, one can imagine several different oligomeric conformations with similar energies that can satisfy tetrahedral Zn coordination (Fig. 8 inset). As it turns out, even a single set of salt bridges can make the difference between the formation of a discrete oligomeric assembly (Zn4:MBPC-14 or Zn4:MBPC-24) and a heterogeneous mixture.25

Such sensitivity to secondary, non-covalent interactions makes our goal of predictably forming discrete superprotein architectures challenging. At the same time, access to these secondary interactions provides an additional handle to control MDPSA, and importantly, to influence the coordination environment of the metal ions embedded in protein-protein interfaces. These possibilities are discussed below.

Metal-Templated Interface Redesign

Despite having access to only a handful of metal coordinating groups, the ability of proteins to control and harness the reactivity of metal centers is unmatched in small molecule metal complexes. This is primarily due to the highly-evolved non-covalent bonding networks of proteins, within which the coordination and solvation environments of metals can be exquisitely tuned.

Since one of the goals of MDPSA is to engineer functional metal coordination sites within protein interfaces, we found it useful to think about how functional metal centers and the surrounding protein environments may have evolved in natural systems. It is probable that some metals were incorporated into pre-existing protein scaffolds that presented the right coordination spheres, which subsequently were optimized for metal-based functions through cycles of natural selection. The feasibility of this evolutionary route is amply demonstrated by de novo designed metalloproteins which are based on pre-existing protein folds.15,16 It is also quite likely that early in the evolution of proteins, metals could initially have nucleated the assembly of random peptides or proteins around them, followed by rigidification and optimization of the surrounding peptide chain(s) for metal reactivities beneficial to a particular organism. With this hypothetical evolutionary time course in mind, we developed a rational engineering approach, Metal Templated Interface Redesign (MeTIR) (Figure 9).28

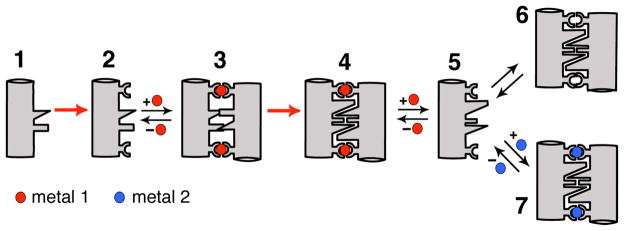

Figure 9.

Cartoon outline for MeTIR. 1. Protein/peptide with a non-self-associating surface; 2. 1 modified with metal coordinating groups; 3. Initial Metal1-templated protein complex with non-complementary interfaces; 4. Metal1-templated protein complex with optimized, complementary interfaces; 5. Protein with a self-associating surface; 6. Metal-independent protein complex biased towards Metal1 binding; 7. Protein complex with distorted Metal2 coordination.

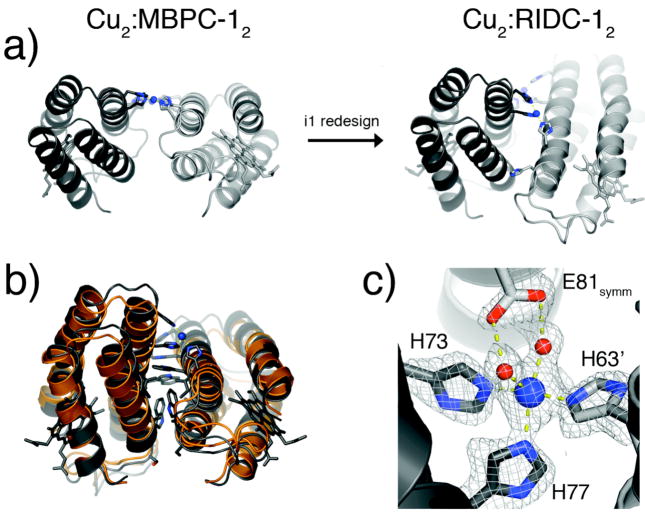

Computationally-guided redesign of Zn-templated interfaces

As illustrated in Fig. 9 (Species 3), the first critical step for MeTIR is the initial complexation of non-self-interacting proteins by metal coordination. The stage for MeTIR is therefore already set by the aforementioned Zn-, Cu- and Ni-mediated superprotein architectures. We chose Zn4:MBPC-14 as the initial focus of surface redesign efforts, because it features the most extensive set of contacts among its monomeric components. The majority of PPIs in Zn4:MBPC-14 are found over two pairs of interfaces i1 and i2 (Fig. 10). We envisioned that these non-specific protein surfaces could be optimized through computational design for favorable packing, which should not only stabilize the tetrameric assembly, but also its specificity for Zn binding.

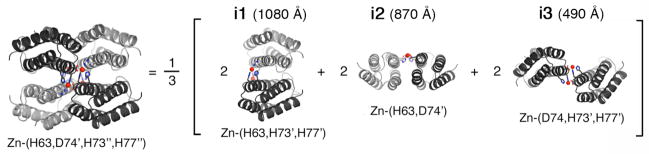

Figure 10.

Three pairs of interfaces (i1, i2, i3) formed within the Zn4:MBPC-14 tetramer; Zn-coordination environment in each interface is listed below.

Using Rosetta29 – in collaboration with Xavier Ambroggio and Brian Kuhlman – we consecutively reengineered interfaces i1 and i2 in Zn4:MBPC14 (Fig. 11). Computational optimization of i1 converged on six specific mutations (R34A/L38A/Q41W/K42S/D66W/V69I), which would yield a well-packed hydrophobic core. We termed the resulting protein construct RIDC-1. Optimization runs for i2 also yielded six target mutations (I67L/Q71A/A89K/Q93L/T96A/T97I). Given the less-than-optimally packed core of redesigned i2, we predicted that it would not contribute significantly to the stability of the Zn-induced tetramer on its own. Hence, we constructed the second-generation variant, RIDC-2, which includes the six calculated mutations in i2 in addition to the six incorporated into i1.28

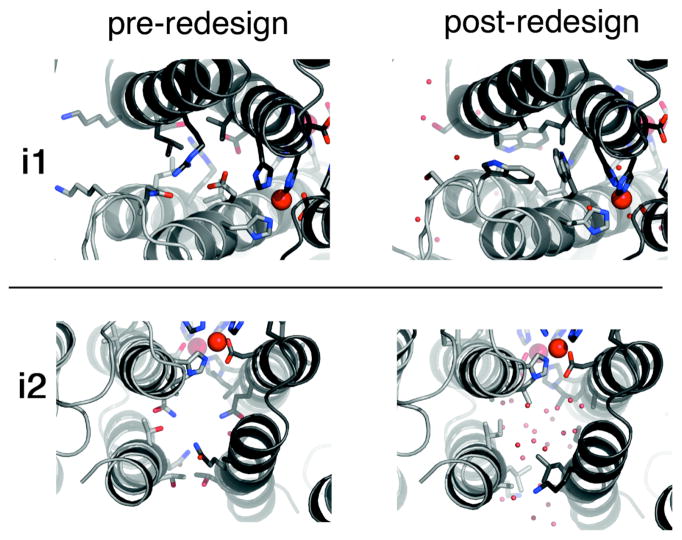

Figure 11.

Detailed view of the crystalographically-characterized sidechain conformations in i1 and i2 before (left) and after (right) redesign (Zn – large red spheres; water molecules – small red spheres.)

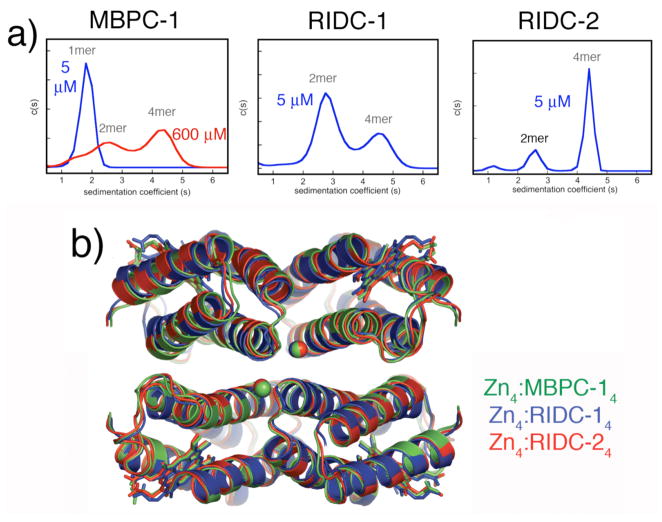

In accord with our predictions, the redesign of i1 leads to a significant stabilization of the Zn-induced tetramer as shown by SV measurements (Fig. 12a). Again as expected, the optimization of i2 expectedly has a small incremental effect. Significantly, the overall structures of Zn4: RIDC-14 and Zn4: RIDC-24 assemblies are identical to the parent Zn4: MBPC-14 complex as intended by “templating” (Fig. 12b) despite 24 total interfacial mutations in Zn4:RIDC-14 and 48 in Zn4:RIDC-24.28

Figure 12.

(a) From left to right: Sedimentation coefficient distributions for MBPC-1, RIDC-1 and RIDC-2 in the presence of equimolar Zn(II). (b) Backbone superposition of Zn4:MBPC-14 (green), Zn4:RIDC-14 (blue), and Zn4:RIDC-24 (red).

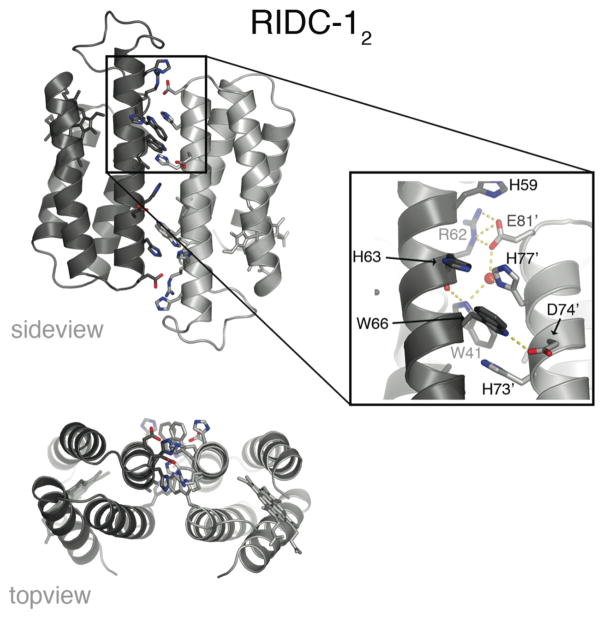

Programming the memory of metal coordination onto protein surfaces

Because the redesign of i1 introduces an extensive set of hydrophobic residues, we examined whether this interface could sustain stable monomer-monomer interactions also in the absence of metals. Hydrodynamic measurements show that RIDC-1 indeed forms a stable metal-free dimer (RIDC-12) with a dissociation constant of ~30 μM.28 The crystal structure of RIDC-12 confirms that the dimer interface is predominantly formed along Helix2 and 3 where most of the hydrophobic mutations – especially the Trp’s – were incorporated (Fig. 13).28 The antiparallel monomer-monomer alignment in RIDC-12 is somewhat distorted from the crisscrossed arrangement of monomers across i1 in Zn4:RIDC-14. This suggests that the engineered hydrophobic interactions do not impose strict geometric specificity, but they do orient the monomers to form a complex that closely approximates the conformation induced by Zn coordination.

Figure 13.

Side and topviews of the RIDC-12 crystal structure, along with the closeup of one of the two symmetrical interaction zones in the dimer interface detailing the interfacial contacts. An ordered water molecule is highlighted as a red sphere.

The fact that RIDC-1 forms a metal-independent dimer suggests that the contribution of i1 mutations to Zn4:RIDC-14 stability is not only enthalpic, but also entropic. Dimerization of RIDC-1 halves the number of protein components towards tetramerization, while preorganizing the Zn-coordinating residues (H63 from one monomer, and H73′/H77′ from a second monomer) into close proximity. In the energy landscape model, the Zn-templated redesign of the MBPC-1 surface (to make RIDC-1) thus constrains the conformational search space towards the formation of the desired tetramer and restricts the number of possible protein complexes with a given ICN, ultimately giving rise to steeper funnel with a deeper well (Fig. 8b).

An implication of the increased stability of the Zn-induced tetramer is the rigidification of the tetrahedral Zn-coordination environment, which should raise Zn affinity and specificity. Conversely, this rigidification should lead a decreased preference for other metals with non-tetrahedral coordination geometries. This is indeed borne out by the crystal structure of the Cu(II) complex of RIDC-1, Cu2:RIDC-12 (Fig. 14a).28 Whereas Cu(II) originally dictated a flat, antiparallel arrangement of two parent MBPC-1 molecules through a square planar His4 coordination in Cu2:RIDC-12 (Fig. 4), it is now found in an open coordination environment with a His3-(H2O)1 or 2 ligand set (Fig. 14b). This unfavored, “high-energy” configuration of Cu(II) is produced by the crisscrossed arrangement of the RIDC-1 monomers, which – just like in the Zn-induced tetramer – brings H63 and H73′/H77′ in close proximity, while pushing H59 out of the coordination sphere (Fig. 14c). These results suggest that the memory of Zn coordination has indeed been programmed onto the RIDC-1 surface, which significantly alters the energy landscape for Cu-mediated self-assembly, such that the lowest energy conformation is no longer defined solely by coordinative saturation.

Figure 14.

(a) Influence of Zn-templated interfacial mutations in i1 on the conformations of Cu-mediated dimeric assemblies. (b) Backbone superposition of Cu2:RIDC-12 (grey) and a dimeric half of Zn4:RIDC-14 (orange) that contains i1. (c) Cu coordination environment in Cu2:RIDC-12, highlighting the open coordination sites occupied by two water molecules. The Glu81 sidechain from a crystallographic symmetry-related dimer is also shown.

What we’ve learned and what lies ahead

In traditional inorganic chemistry circles, proteins are sometimes referred to as “spaghetti” or “chicken fat” that surround the precious metal ions. In the bioinorganic community, proteins are treated with a little more awe; this has prompted the entire field of biomimetic model chemistry, which aims to elucidate the inner workings of metal centers without the intricacies of the surrounding protein framework. No matter what the perspective, there is no denying that proteins are sophisticated metal ligands that guide metals to impressive chemical feats.

When we embarked on our endeavor four years ago, we took the notion of “proteins are ligands” somewhat literally. Could we use individual, folded proteins as ligands, and control their self-assembly through metal coordination? We were - and still are – interested in this question from both biological and inorganic perspectives. Can we build complex multi-protein assemblies like Nature does every time it needs to do something more involved than what is achievable with simpler, single protein systems (e.g., photosynthesis, respiration, nitrogen fixation)? At the same time, can we construct novel inorganic sites in biological interfaces, exploiting the functionality – and functionalizability – of protein surfaces to rule over the reactivities of these sites? The work that we have described in this Account not only showed us the feasibility of these goals, but also opened our eyes to new research prospects like the possible roles of metal ions in the evolution of protein folds/complexes and de novo design of protein interfaces.

One thing that we’ve certainly learned along the way is that proteins indeed make complicated ligands, which – more often than not – interact with metals and assemble in ways that are hard to predict. This is the major hurdle that still remains before we can construct made-to-order metalloprotein assemblies with tailored functions. Another hurdle is the technical difficulty of monitoring the dynamics of protein self assembly and obtaining detailed chemical information about the protein complexes formed in solution, especially at low protein concentrations (which are readily accomplished through NMR in the case of small molecules). Yet, with perfect hindsight afforded by structural studies and some inorganic intuition, mixed in with a bit of computational protein design and advances in NMR and perhaps mass spectroscopy, we are certain that these hurdles will be overcome. We hope that others join in the fun.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xavier Ambroggio for his guidance on computational interface redesign. This work was supported by NIH Training Grants (E.N.S and R.J.R.), an NIH Predoctoral Fellowship (E.N.S.), a Beckman Young Investigator Award (F.A.T.) and NSF (CHE-0908115).

Biographies

Eric Salgado received his B.S. in Biochemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 2004, where he worked with Susan Cumberledge and Scott Garman. He was recently awarded an NIH predoctoral fellowship to complete his Ph.D. studies at UCSD.

Robert Radford received his B.S. in Chemistry at the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2006, where he studied the photochemistry of metal-nitrosyl complexes with Peter Ford. In 2008, he was honored with a Saltman Excellent Teaching Award at UCSD.

Akif Tezcan received his B.A. in Chemistry at Macalester College and his Ph.D. under the direction of Harry Gray at Caltech, where he was also a postdoctoral fellow with Doug Rees. He has been an Assistant Professor at UCSD since 2005.

References

- 1.Shoemaker BA, Panchenko AR. Deciphering protein-protein interactions. Part I. Experimental techniques and databases. Plos Comput Biol. 2007;3:337–344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher S, Hamilton AD. Targeting protein-protein interactions by rational design: mimicry of protein surfaces. J R Soc Interface. 2006;3:215–233. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kortemme T, Baker D. Computational design of protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leininger S, Olenyuk B, Stang PJ. Self-assembly of discrete cyclic nanostructures mediated by transition metals. Chem Rev. 2000;100:853–907. doi: 10.1021/cr9601324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holliday BJ, Mirkin CA. Strategies for the construction of supramolecular compounds through coordination chemistry. Angew Chem, Int Ed Eng. 2001;40:2022–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshizawa M, Klosterman JK, Fujita M. Functional Molecular Flasks: New Properties and Reactions within Discrete, Self-Assembled Hosts. Angew Chem-Int Edit. 2009;48:3418–3438. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allendorf MD, Bauer CA, Bhakta RK, Houk RJT. Luminescent metal-organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1330–1352. doi: 10.1039/b802352m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bo W, Cote AP, Furukawa H, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Colossal cages in zeolitic imidazolate frameworks as selective carbon dioxide reservoirs. Nature. 2008:207–11. doi: 10.1038/nature06900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pluth MD, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. Acid catalysis in basic solution: A supramolecular host promotes orthoformate hydrolysis. Science. 2007;316:85–88. doi: 10.1126/science.1138748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertini I, Gray HB, Stiefel EI, Valentine JS. Biological Inorganic Chemistry, Structure & Reactivity. University Science Books; Sausolito: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emsley J, Knight CG, Farndale RW, Barnes MJ, Liddington RC. Structural basis of collagen recognition by integrin alpha 2 beta 1. Cell. 2000;101:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou TQ, Hamer DH, Hendrickson WA, Sattentau QJ, Kwong PD. Interfacial metal and antibody recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14575–14580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507267102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Yeung N, Sieracki N, Marshall NM. Design of functional metalloproteins. 2009;460:855–862. doi: 10.1038/nature08304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KH, Matzapetakis M, Mitra S, Neil E, Marsh G, Pecoraro VL. Control of metal coordination number in de novo designed peptides through subtle sequence modifications. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9178–9179. doi: 10.1021/ja048839s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddi AR, Reedy CJ, Mui S, Gibney BR. Thermodynamic investigation into the mechanisms of proton-coupled electron transfer events in heme protein maquettes. Biochemistry. 2007;46:291–305. doi: 10.1021/bi061607g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koder RL, Anderson JLR, Solomon LA, Reddy KS, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Design and engineering of an O2 transport protein. Nature. 2009;458:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature07841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayashi H, Cote AP, Furukawa H, O’Keeffe M, Yaghi OM. Zeolite a imidazolate frameworks. Nat Mater. 2007;6:501–506. doi: 10.1038/nmat1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faraone-Mennella J, Tezcan FA, Gray HB, Winkler JR. Stability and folding kinetics of structurally characterized cytochrome cb562. Biochemistry. 2006;45:10504–10511. doi: 10.1021/bi060242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janin J, Rodier F. Protein-protein interaction at crystal contacts. Proteins. 1995;23:580–587. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold FH, Haymore BL. Engineered Metal-Binding Proteins - Purification To Protein Folding. Science. 1991;252:1796–1797. doi: 10.1126/science.1648261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salgado EN, Faraone-Mennella J, Tezcan FA. Controlling Protein-Protein Interactions through Metal Coordination: Assembly of a 16-Helix Bundle Protein. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13374–13375. doi: 10.1021/ja075261o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghadiri MR, Choi C. Secondary Structure Nucleation in Peptides - Transition-Metal Ion Stabilized Alpha-Helices. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:1630–1632. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado EN, Lewis RA, Mossin S, Rheingold AL, Tezcan FA. Control of Protein Oligomerization Symmetry by Metal Coordination: C2 and C3 Symmetrical Assemblies through CuII and NiII Coordination. Inorg Chem. 2009;48:2726–2728. doi: 10.1021/ic9001237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radford RJ, Tezcan FA. A Superprotein Triangle Driven by Nickel(II) Coordination: Exploiting Non-Natural Metal Ligands in Protein Self-Assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9136–9137. doi: 10.1021/ja9000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salgado EN, Lewis RA, Faraone-Mennella J, Tezcan FA. Metal-mediated self-assembly of protein superstructures: Influence of secondary interactions on protein oligomerization and aggregation. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6082–6084. doi: 10.1021/ja8012177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bryngelson JD, Onuchic JN, Socci ND, Wolynes PG. Funnels, Pathways, and the Energy Landscape of Protein-Folding - a Synthesis. Proteins. 1995;21:167–195. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salgado EN, Ambroggio XI, Brodin JD, Lewis RA, Kuhlman B, Tezcan FA. Metal Template Design of Protein Interfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906852107. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, Kuhlman B. RosettaDesign server for protein design. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:W235–238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]