Abstract

To investigate the consequences of possible physiological stress to embryos caused by the in vitro fertilization procedures, we used as a model heat shock response in preimplantation mouse embryos. A heat shock “memory” was discovered that renders cleavage-stage embryos more responsive at the transcriptional level to secondary perturbation with very low doses of heat, even several cell cycles after the initial stress has occurred.

Keywords: Preimplantation mouse embryo, Heat shock protein, Heat shock memory, hsp70

Over the past thirty years, more than 1% of births in the US and as many as 4% in Denmark have been initiated using some form of in vitro fertilization (IVF) (1). There is now increasing concern and investigation into whether such procedures have long-term consequences that may or may not be obvious at birth (2, 3). Indeed, recent studies suggest that IVF is associated with some rare genetic syndromes such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (4, 5) and Angelman Syndrome (6). An increased risk of several birth defects in IVF babies was also reported (7, 8).

IVF includes a wide variety of treatments and protocols and no rigorous investigations of altered gene expression in preimplantation human embryos are available for any of them. However, both short-term and long-term effects of environmental conditions on preimplantation mouse embryos have been analyzed. Ecker et al. transferred genetically marked blastocysts grown in vivo, along with blastocysts cultured under different conditions in vitro, into the same foster mother and then tested the resulting sibling mice for their capacities to perform in a maze (9). The results clearly show that mice born from embryos cultured in vitro were not as maze-bright as mice derived from embryos grown in vivo. Moreover, mice obtained from cultured embryos lacked the caution and fear that normal mice are born with. At the molecular level, genome wide patterns of DNA methylation and gene expression were different in embryos cultured in vitro for a few days as compared to those grown in vivo to the equivalent stages of development (10, 11).

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are expressed in virtually all cells in response to environment stressor and serve to protect the cells from heating and toxic substances, which might occur during embryo culture (12-14). The phenomenon of thermotolerance, a first mild heat exposure of the embryo protecting it from a second more severe heat shock, has been observed in postimplantation mouse embryos (15-17). It was suggested that HSP70 has a direct role in the induction of thermotolerance and that the level of thermotolerance can be correlated to the level of HSP70 protein (16). Although inducible expression of the hsp70i genes (hsp70.1 and hsp70.3) is observed in mouse embryos starting at the 4-cell stage (18), the relationship between hsp70i gene expression and thermotolerance in preimplantation embryos is unclear..

Our previous work has shown that ablation of the zona pellucida with a laser does not induce heat shock in preimplantation mouse embryos (19). Here using hsp70i mRNA transcription as a model, we show for the first time that a mild heat shock at the 8-cell stage renders mouse embryos more responsive at the level of hsp70i mRNA accumulation to a second shorter heat shock delivered even several cell cycles later. Two-cell stage mouse embryos from Embryotech Laboratores, Inc were cultured as described elsewhere (20). Single cells were isolated from 8-cell stage embryos through a hole in the zona pellucida generated using a ZILOS-tk™ laser optical system (19). The PurAmp single-tube method (21) was used for lysing single cells or whole embryos and for analyzing them by real-time one-step RT-LATE-PCR (22, 23) in the same vessel. This method measured total template copy numbers (hsp70i mRNA + hsp70i genomic DNA) because the hsp70i genes are intronless. hsp70i genomic DNA amounts to four copies per cell. RT-PCR was run in 50 μl reaction with 50 nM limiting primer, 5′-CAGCGTCC TCTTGGCCCTCTCACAC-3′, 2 μM excess primer, 5′-GATCGACGACGGCATCTTC-3′, 500 nM. Probe, BHQ1-5′-GATCCTCTTGAACTCCTTC-3′-Cal Orange 560 (BHQ1: Black Hole Quencher 1) along with 300 nM Primesafe I™ (Smith Detection, UK) (24), and 1 μl of SSIII/Platinum Taq mixture (Invitrogen, 11732) in standard PCR buffer (Invitrogen, 11304). The cycling profile was: 55°C for 15 minutes (RT); 95°C for 5 minutes; 15 cycles consisting of the following three steps: 95°C (10 sec), 63°C (20 sec) and 72°C (30 sec); 35 cycles with the following four steps: 95°C (15 sec), 55°C (25 sec), 72°C (35 sec) and 45°C (30 sec) (Fluorescence reading). Standard curves for template copy number quantification were generated with the same pair of primers, using a template of purified mouse genomic DNA (Sigma, D4416) in serial dilutions.

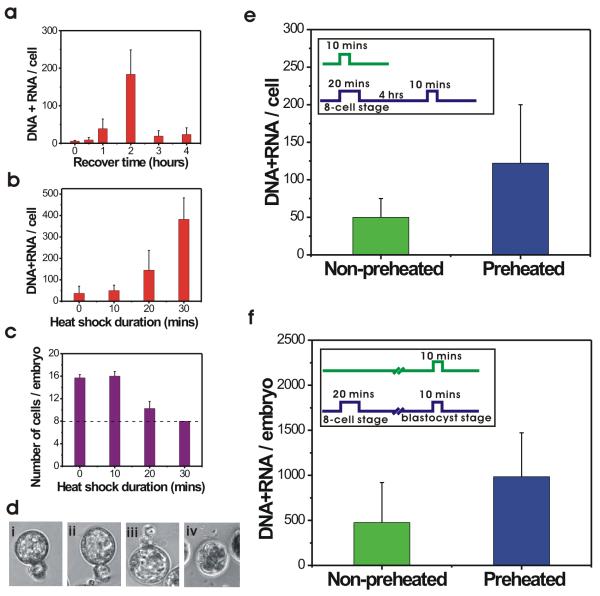

Levels of hsp70i mRNA per cell in 8-cell stage embryos (cultured for 24 hours from 2-cell stage) heated for 20 minutes at 43°C reached maximum levels two hours after treatment and then returned to normal after four hours (Fig 1a). A heating period of only 10 minutes did not result in elevated hsp70i mRNA after two hours of recovery, while the average number of hsp70i templates per cell following 20 or 30 minutes of heating was found to be, respectively, 145 (± 92) and 383 (± 100). Thus, levels of hsp70i mRNA gene expression correlate with the length of heat shock (Fig 1b).

Figure.

a) hsp70i mRNA transcription in single cells isolated from 8-cell stage embryos after 20 minutes of heat shock and different recovery times; the bars show average hsp70i mRNA + DNA levels per cell plus standard deviation; b) Average hsp70i mRNA transcription in single cells from 8-cell stage embryos after heat shock of different duration; c) Average number of cells per embryo, 20 hours after heat shock at the 8-cell stage for different lengths of time; d) Embryo morphologies 48 hours after heat shock at the 8-cell stage for i) no heat shock; ii) 10 mins; iii) 20 mins; iv) 30 mins. e) Double heat shock effect on hsp70i expression in single cells from embryos at the 8-cell stage. The green bar shows average hsp70i mRNA + DNA levels in embryos that had been heat-shocked only once, for 10 minutes at the 8-cell stage (cultured for 24 hours). The blue bar shows average hsp70i mRNA + DNA levels in embryos that had been preheated for 20 minutes at the 8-cell stage (cultured for 24 hours) and then heated again for 10 minutes after a 4-hour recovery period; f) Long term double heat shock effect in blastocyst stage mouse embryos (cultured for 72 hours). The green bar shows average hsp70i mRNA + DNA levels in embryos heat-shocked for 10 minutes at the blastocyst stage. The blue bar shows average hsp70i mRNA + DNA levels in embryos preheated for 20 minutes at 8-cell stage, then heat-shocked again for 10 minutes at the blastocyst stage. The average number of hsp70i mRNA + DNA copies per cell was obtained using 30-50 single cells from each group of embryos.

The fact that longer heating results in higher hsp70i mRNA accumulation does not, however, guarantee that embryos treated for 20 or 30 minutes are equally able to recover from stress. Embryos heated for 30 minutes at the 8-cell stage and then cultured for an additional 48 hours at 37°C failed to undergo cell division and eventually died. In contrast, embryos heated for 10 minutes continued to grow just like control embryos, while embryos treated with heat for 20 minutes paused cell division for several hours (Fig 1c) and then resumed growth and development to blastocyst stage 48 hours after heat shock. Thus, although the time needed to initially reach blastocyst stage was not the same for untreated embryos and embryos heated for 20 minutes, both sets of embryos were morphological similar after 48 hours, with a well formed blastocoel having an inner cell mass on one side (Fig 1d). Both sets of embryos also went on to hatch.

In order to study preimplantation embryos’ response to double heat shock, we exposed 8-cell stage embryos to 20 minutes of heat and then, after a gap of 4 hours, tested them for thermotolerance by heating them again for either 10 or 30 minutes. Primary heat treatment for 20 minutes did not prevent developmental arrest and death caused by a 30-minute heating, demonstrating that these embryos were not rendered thermotolerant, even though they had actively transcribed hsp70i mRNA in response to the first heat treatment.

We next investigated whether a primary exposure to heat could, in fact, sensitize the embryo to secondary heat treatment. One group of 8-cell stage embryos was heat-treated for 20 minutes, allowed to recover for 4 hours, and then heated again for 10 minutes. The level of hsp70i mRNA in the cells of these embryos was compared to that of embryos which were heated only once for 10 minutes. Because the embryos paused in their development following the 20 minutes heat shock (Fig 1c), both groups of embryos were at the 8-cell stage during all phases of this experiment. The results in Fig 1e show that single cells from embryos heated only once contained an average of 50 (± 25) copies of hsp70i mRNA + DNA. In contrast, double heat-shocked embryos had an average of 122 (± 78) copies of mRNA + DNA per cell, demonstrating that the initial 20-minute treatment sensitized these cells to secondary heating. We call this phenomenon heat shock “memory” in preimplantation mouse embryos.

These results led us to investigate whether heat shock memory would persist through one or more rounds of DNA replication and cell division. To test this possibility we once again heated a group of about twenty 8-cell embryos for 20 minutes and then grew them to the blastocyst stage (cultured for 72 hours from 2-cell stage). At this point the embryos were heated a second time for just 10 minutes. A second group of about twenty control embryos was not heated at the 8-cell stage, but were exposed to heat for 10 minutes when they reached the blastocyst stage (cultured for 72 hours from 2-cell stage). Because single cells cannot readily be dissected out of blastocyst stage embryos, we analyzed whole embryos and measured the hsp70i mRNA + DNA copy numbers two hours after the 10-minute heat treatment.

As shown in Fig 1f, the double heat-shocked embryos contained on the average 984 (± 478) copies of hsp70i templates per embryo while the embryos heat-shocked once yielded only 476 (± 444) copies of hsp70i templates per embryo, a ratio of about 2:1. The ratio of hsp70i mRNA molecules per cell in the double heat-shocked embryos versus embryos heated once, however, is likely to be significantly higher because the first exposure to heat had arrested cell division for several hours. Therefore, the blastocysts preheated at the 8-cell stage contain fewer cells, on average, than the control blastocysts. Heat-shock induced cell cycle arrest is a well known phenomenon (25). For instance, the number of cells in heat shocked bovine preimplantation embryos is 2/3 of that in control embryos (26). The higher response in the blastocyts first heat-treated at the 8-cell stage demonstrates that heat shock “memory” persists through several cell divisions.

The results presented here raise many intriguing questions and hypotheses. What is the full set of genes in the preimplantation embryo sensitized by primary heat treatment? Can these genes be affected or activated (if stress-inducible) by chemicals which activate heat shock genes in other cell systems (27, 28)? What is the molecular mechanism of long-term heat shock “memory”? It is known that hsp70i genes are methylated in mammalian cells (29). Thus, similar to the findings of Ecker et al. (9), it is plausible that primary heat treatment triggers a change in DNA methylation within the promoters of these genes and that this epigenetic change persists in daughter cells, rendering them more sensitive to secondary heat treatment. If such mechanisms are shown to be true, the same epigenetic changes may be stable through embryonic, fetal, and neonatal development. Such a scenario could mean increased sensitization to a secondary stress, at least in some cell lineage. Validation of these hypotheses will require a great deal more research in the mouse but the resulting information will have critical importance for the growth and development of human embryos conceived both in vitro and in utero.†

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from NIH Centers for Excellence Genomic Sciences award P50 HC002360-06 to the “Microscale Life Science Center”.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

“The Predestinators send in their figures to the Fertilizers.” “Who give them the embryos they ask for”. “And the bottles come in here to be predestinated in detail.”...... “Heat conditioning” said Mr. Foster. Hot tunnels alternated with cool tunnels. Coolness was wedded to discomfort in the form of hard X-ray. By the time they were decanted the embryos had a horror of cold. They were predestined to emigrate to the tropics, to be miners and acetate silk spinners and steel workers.... “We condition them to thrive on heat,” concluded Mr. Foster. Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chandra A, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U. S. women: data from the 2002 national Survey of Family Growth. Vital Health Stat. 2005;23:1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. The biology of infertility: research advances and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2008;14:1197–213. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nair P. As IVF becomes more common, some concerns remain. Nat Med. 2008;14:1171. doi: 10.1038/nm1108-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBaun MR, Niemitz EL, Feinberg AP. Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:156–60. doi: 10.1086/346031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manipalvirat S, DeCherney A, Segars J. Imprinting disorders and assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:305–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cox GF, Bürger J, Lip V, Mau UA, Sperling K, Wu B-L, et al. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection may increase the risk of imprinting defects. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:162–4. doi: 10.1086/341096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olson CK, Keppler-Noreuil KM, Romitti PA, Budelier WT, Ryan G, Sparks AET, et al. In vitro fertilization is associated with an increase in major birth defects. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reefhuis J, Honein MA, Schieve LA, Correa A, Hobbs CA, Rasmussen SA, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and major structural birth defects in the United States. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:360–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ecker DJ, Stein P, Xu Z, Williams CJ, Kopf GS, Bilker WB, et al. Long-term effects of culture of preimplantation mouse embryos on behavior. Proc NatL Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1595–600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306846101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinaudo P, Schultz RM. Effects of embryo culture on global pattern of gene expression in preimplantation mouse embryos. Reproduction. 2004;128:301–11. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rivera RM, Stein P, Weaver JR, Mager J, Schultz RM, Bartolomei MS. Manipulations of mouse embryos prior to implantation result in aberrant expression of imprinted genes on day 9.5 of development. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1–14. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burel C, Ezger MV, Pinto M, Rallu M, Trigon S, Morange M. Mammalian heat-shock protein families -expression and functions. Experientia. 1992;48:629–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02118307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samali A, Cotter TG. Heat shock proteins increase resistance to apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 1996;223:163–70. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.dePomerai D, Daniells C, David H, Allan J, Duce I, Mutwakil M, et al. Non-thermal heat-shock response to microwaves. Nature. 2000;405:417–8. doi: 10.1038/35013144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KapronBras CM, Hales BF. Heat-shock induced tolerance to the embryotoxic effects of hyperthermia and cadmium in mouse embryos in vitro. Teratology. 1991;43:83–94. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420430110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirkes PE, Cornel LM, Wilson KL, Dilmann WH. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) protects postimplantation murine embryos from the embryolethal effects of hyperthermia. Dev Dyn. 1999;214:159–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199902)214:2<159::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matwee C, Kamaruddin M, Betts DH, Basrur PK, King WA. The effects of antibodies to heat shock protein 70 in fertilization and embryo development. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:829–37. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.9.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartshorn C, Anshelevich A, Jia Y, Wangh LJ. Early onset of heat-Shock response in mouse embryos revealed by quantification of stress-inducible hsp70i RNA. Gene Regul Syst Bio. 2007;1:365–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartshorn C, Anshelevich A, Wangh LJ. Laser zona drilling does not induce hsp70i transcription in blastomeres of eight-cell mouse embryos. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1547–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartshorn C, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Developmentally-regulated changes of Xist RNA levels in single preimplantation mouse embryos, as revealed by quantatitive real-time PCR. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;61:425–36. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartshorn C, Anshelevich A, Wangh LJ. Rapid, single-tube method for quantitative preparation and analysis of RNA and DNA in samples as small as one cell. BMC Biotechnol. 2005;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierce KE, Sanchez JA, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Linear-After-The-Exponential (LATE)-PCR: Primer design criteria for high yields of specific singlestranded DNA and improved real-time detection. Proc NatL Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8609–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501946102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanchez JA, Pierce KE, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Linear-After-The-Exponential (LATE)–PCR: An advanced method of asymmetric PCR and its uses in quantitative real-time analysis. Proc NatL Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305476101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice JE, Sanchez JA, Pierce KE, Jr AHR, Osborne A, Wangh LJ. Monoplex/multiplex linear-after-the-exponential-PCR assays combined with PrimeSafe and Dilute-‘N’-Go sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2429–38. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kühl NM, Rensing L. Heat shock effects on cell cycle progression. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:450–63. doi: 10.1007/PL00000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jousan FD, Hansen PJ. Insulin-like Growth Factor-I as a Survival Factor for the Bovine Preimplantation Embryo Exposed to Heat Shock. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1665–70. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li GC, Laszlo A. Amino acid analogs while inducing heat shock proteins sensitize CHO cells to thermal damage. J Cell Physiol. 1985;122:91–7. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041220114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuller DJM, Gerner EW. Sensitization of chinese hamster ovary cells to heat shock by a-Difluoromethylornithine1. Cancer Res. 1987;47:816–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Gomer RH, Lazarides E. Heat shock proteins are methylated in avian and mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3531–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]