Abstract

Forced expression of the four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 is sufficient to confer a pluripotent state upon the murine fibroblast genome, generating induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Although felt to be equivalent to embryonic stem (ES) cells, the differentiation potential of these cells has not been rigorously determined. In this study, we sought to identify the capacity of iPS cells to differentiate into Flk1-positive progenitors and their mesodermal progeny including cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages. Immunostaining of tissues from iPS cell-derived chimeric mice demonstrated that iPS cells could contribute in vivo to cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle, endothelial and hematopoietic cells. To compare the in vitro differentiation potential of murine ES and iPS cells, we either induced embryoid body (EB) formation of each cell type or cultured the cells on collagen type IV (ColIV), an extracellular matrix protein that had been reported to direct murine ES cell differentiation to mesodermal lineages. EB formation as well as exposure to ColIV both induced iPS cell differentiation into cells that expressed cardiovascular and hematopoietic markers. To determine if ColIV-differentiated iPS cells contained a progenitor cell with cardiovascular and hematopoietic differentiation potential, Flk1-positive cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting and exposed to specific differentiation conditions, which induced differentiation into functional cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle, endothelial and hematopoietic cells. Our data demonstrate that murine iPS cells, like ES cells, can differentiate into cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages and therefore may represent a valuable cell source for applications in regenerative medicine.

Keywords: induced pluripotent stem cells, embryonic stem cells, reprogramming, extracellular matrix, collagen IV, cardiovascular

Introduction

Differentiation of the cells of the inner cell mass into the specialized cells required for the formation of the complex tissues that comprise living organisms has traditionally been viewed as a unidirectional process, with cells in the embryo becoming gradually committed to a specific cell type. However, somatic cell nuclear transfer experiments have demonstrated that the oocyte can return the nucleus of an adult somatic cell to a pluripotent embryonic-like state (1, 2). While little is known about the factors in the oocyte that induce this process, several recent reports have described the ability of four transcription factors whose retroviral overexpression enabled the induction of a pluripotent, embryonic stem (ES) cell-like state in murine fibroblasts. Simultaneous overexpression of the pluripotency-associated POU domain class 5 transcription factor 1 (Oct4), SRY-box containing gene 2 (Sox2), proto-oncogene c-Myc, and Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) led to the generation of induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells that exhibited the morphology and growth properties similar to ES cells and expressed ES cell marker genes (3). A significant improvement of this in vitro reprogramming approach was then demonstrated by using different strategies for selecting the reprogrammed cells, generating murine iPS cells that functionally resembled ES cells and that were competent for formation of germline chimera (4-6). More recently investigators have created iPS cells from adult human cells using either a combination of Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4 similar to the mouse system (7, 8); or Oct4, Sox2, Nanog homeobox (Nanog), and lin-28 homolog (LIN28) (9). These human iPS cells have normal karyotypes, express telomerase activity, cell surface markers and genes that typify human ES cells, and maintain the developmental potential to differentiate into advanced derivatives of all three primary germ layers (7-9). The successful reprogramming of human somatic cells into a pluripotent ES cell-like state could provide a method to generate customized, patient-specific pluripotent cells for regenerative medicine efforts. However, this assumes that iPS cells possess a similar differentiation potential to ES cells, and to critically study the differentiation behavior of iPS cells will be essential for iPS cell-based therapies to become clinical reality.

In this study, we sought to characterize the differentiation potential of murine 2D4 iPS cells (4) and compare it to murine D3 ES cells. Immunostaining of tissues from iPS cell-derived chimeric mice (4) demonstrated that iPS cells differentiated in vivo into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells (SMC), endothelial cells (EC) and hematopoietic cells suggesting they might also possess this potential in vitro. We utilized two alternate approaches to initiate differentiation in ES and iPS cells: embryoid body (EB) formation and exposure to collagen type IV (ColIV), an extracellular matrix protein that had been reported to direct ES cell differentiation to mesodermal lineages, including SMC, EC and hematopoietic cells in both mouse (10-13) and human (14) cultures. Similar to results seen in murine ES cell differentiation experiments, iPS cell-derived EBs as well as ColIV-differentiated iPS cells demonstrated upregulation of mesodermal genes associated with cardiac, cardiovascular and hematopoietic cells. It has been reported that a multipotential cardiovascular progenitor cell can be isolated from ES cell-derived EBs, characterized by the expression of kinase insert domain protein receptor (Flk1/Kdr) and the mesodermal marker brachyury, that can give rise to cells of the cardiovascular lineage (15). Likewise, presumed derivatives of this cell, which several groups have described as Flk1-, Kit oncogene (c-kit/CD117)-, NK2 transcription factor related, locus 5 (Nkx2.5)-positive cardiovascular progenitor cells were isolated from EBs and determined to be able to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, SMC and EC (16, 17). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of EB- and ColIV-differentiated iPS cells revealed the presence of Flk1-positive progenitor cells. When isolated by magnetic cell sorting, these ColIV-differentiated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells had the potential to differentiate into functional SMC, EC and spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes. Moreover, when co-cultured on OP9-GFP stroma supplemented with a hematopoietic cytokine cocktail, the Flk1-positive progenitors differentiated into hematopoietic progenitor cells possessing multilineage myelo-erythroid differentiation potential.

Our results suggest that murine iPS cells can be differentiated into cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages and possess a differentiation potential equivalent to ES cells, at least with respect to these lineages. Furthermore, it is possible to isolate a Flk1-positive progenitor cell from differentiating iPS cells with the potential to differentiate into hematopoietic cells and all three cell types of the cardiovascular lineage. Thus, iPS cells could prove a valuable cell source for applications in regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Murine ES and iPS cell cultures

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) carrying a GFP-IRES-puro cassette in the endogenous Nanog locus, were retrovirally reprogrammed into iPS cells with cDNAs encoding Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4 and were reported previously (4) (Suppl. Fig. 1). Specifically, the iPS cell line 2D4 described in (4) was used in the present study. D3 ES cells (CRL-1934; ATCC, Manassas, VA, www.atcc.org) and the Nanog-selected 2D4 iPS cells were maintained in an undifferentiated state on mitomycin-C-treated (M0503; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, www.sigma.com), primary MEF in LIF medium [Knockout Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium (Knockout D-MEM; Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, www.invitrogen.com), supplemented with 15% ES cell-qualified fetal calf serum (ES-FCS (Invitrogen)), 0.1 mM beta-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), and 1000 U/ml recombinant leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF, Chemicon, Temecula, CA, www.chemicon.com)] at 37°C, 5% CO2. All cells were passaged every second day using 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen).

In vitro differentiation assays

For differentiation assays, murine D3 ES and 2D4 iPS cells were either introduced into a dynamic suspension culture system for generating EBs, or they were cultured on collagen type IV-coated plates and flasks. Briefly, for EB formation, cells were dissociated, resuspended in alpha-MEM medium [alpha-Minimum Essential Medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% ES-FCS, 0.1 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM glutamine, and 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, without LIF], transferred in 60 mm ultra low attachment dishes (4 × 105 cells/dish) (Corning Inc. Life Sciences, Lowell, MA, www.corning.com/lifesciences/US-Canada/en/), placed onto an orbital rotary shaker (Stovall Belly Button, Appropriate Technical Resources (ATR) Inc., Laurel, MD, http://www.atrbiotech.com), and cultured under continuous shaking at approximately 45 revolutions per minute (rpm) for up to 14 days, followed by RNA isolation or FACS analysis. For morphometric analysis, phase-contrast images of ES and iPS cell-derived EBs were acquired every second day during the course of culture, and the diameters of at least fifty EBs from three replicate cultures were measured using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood, NY, www.zeiss.com).

For the ColIV-cultures, ES and iPS cells were trypsinized and transferred to collagen type IV-coated plates or flasks (BD Biocoat, BD Bioscience Discovery Labware, Bedford, MA, www.bdbiosciences.com/discoverylabware/) as described before (13). After 4 days the cells were either harvested for RNA isolation and FACS analysis, or they were trypsinized and the Flk1-positive cells were isolated by indirect magnetic cell sorting (MACS) using a purified rat anti-mouse Flk1 antibody (550549 (1:200); BD Bioscience Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, www.bdbiosciences.com/pharmingen/) and magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA, http://www.miltenyibiotec.com). The Flk1-positive cells were then used for RNA isolation, co-cultured on green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing OP9 (OP9-GFP) stromal cells (a kind gift of Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker), or plated on fibronectin-coated culture slides (BD Bioscience Discovery Labware) in either alpha-MEM (cardiac differentiation), PDGF-BB medium [smooth muscle growth medium (SMGM-2; Lonza, Walkersville, MD, www.lonza.com), supplemented with 10 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, www.rndsystems.com)] (SMC differentiation (11, 13)), or VEGF medium [endothelial growth medium (EGM-2; Lonza), supplemented with 50 ng/ml vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF; R&D Systems Inc.)] (EC differentiation (11, 13)) for up to 12 days at 37°C, 5% CO2. To expand the ES and iPS cell-derived SMC or EC, cells were grown to >80% confluence in either SMGM-2 or EGM-2 medium, and passaged into gelatin-coated plates with a 1:2 to 1:3 ratio every 2–3 days. Bright-field images and movies of undifferentiated and differentiated ES and iPS cells as well as EBs were acquired using the Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope.

OP9 co-cultures and colony-forming unit (CFU)-assays

Flk1-positive ES and iPS cell-derived cells were cultured on OP9-GFP stromal cells in 24-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 104 cells per well in 1 ml alpha-Minimum Essential Medium, containing 20% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, www.hyclone.com) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, supplemented with stem cell factor (SCF, 50 ng/ml), interleukin-3 (IL-3, 5 ng/ml), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, 10 ng/ml), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF, 10 ng/ml) and human erythropoieten (hEPO, 20 ng/ml) for up to 7 days (all from PeproTech Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ, www.peprotech.com). Half of the medium with cytokines was replaced every two days. To determine the myelo-erythroid potential of the Flk1-positive progenitors, cells were harvested after 5 days of OP9-GFP co-culture and plated in 1.5 ml methylcellulose that contained SCF, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-3 and EPO (MethoCult 3434; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada, www.stemcell.com). In addition, TPO (5 ng/ml) was added to the methylcellulose cultures. Colonies were scored 5 days later.

Immunochemistry

Immunofluorescence staining of cells and frozen tissue sections of newborn 2D4 iPS cell-derived chimeric mice (4) was performed as described before (13). Detailed information on the primary and secondary antibodies that have been used in this study can be found in the supplemental data file. To visualize the F-actin cytoskeleton, cells were stained using Alexa Fluor 594 phalloidin (1:40; Molecular Probes). For counterstaining of cell nuclei 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma) was added to the final PBS washing. Staining without primary antibodies served as controls. Fluorescence images were acquired using a confocal TCS SP2 AOBS laser-scanning microscope system (Leica Microsystems Inc., Exton, PA, www.leica.com) with 40× (1.3 numerical aperture (NA)) and 63× (1.4 NA) oil-immersion objectives. Images were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, www.adobe.com).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis

Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed in PBS and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-, phycoerythrin (PE)- or allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated monoclonal rat anti-mouse antibodies against Flk1 (PE or APC), CD31 (FITC), CD144 (PE), CD34 (PE, APC) (all 1:200; from BD Pharmingen and eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA, www.ebioscience.com). For detection of vWF, cells were incubated with a rabbit anti-vWF antibody (vWF; ab6994 (1:400); abcam, Cambridge, MA, www.abcam.com), followed by incubation with an Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat-anti rabbit antibody (1:250; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, probes.invitrogen.com). OP9-differentiated Flk1-progenitor cells were stained with PE-, cyanine 5 (Cy5)- and APC-conjugated monoclonal rat anti-mouse antibodies against c-kit (PE), CD41 (Cy5) and CD45 (APC) (all 1:200; from BD Pharmingen). Nonspecific fluorochrome- and isotype-matched IgGs (BD Pharmingen) served as controls. Staining with 7-amino-actinomycin (7-AAD; 559925; BD Pharmingen) was performed to exclude dead cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. OP9-GFP stromal cells were omitted from the analysis based on their GFP expression and side scatter exclusion. All analyses were performed using a BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, www.bdbiosciences.com). FCS files were exported and analyzed using the FlowJo 8.6.3 software (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR, www.flowjo.com).

RNA analysis

Total RNA was extracted from mouse hearts (positive control), as well as from harvested EBs and cells, and semi-quantitative PCR was performed as previously described (13). The sequences of each specific primer set including their annealing temperatures (AT) and cycles are listed in the Supplemental Table 1. The aortic smooth muscle actin (Acta2), caldesmon 1 (Cald1), calponin 2 (Cnn2), platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (Pecam1/CD31), cadherin 5 (Cdh5/CD144/VE-Cadherin) and von Willebrand factor homolog (Vwf) RT-PCR primer sets were obtained from Superarray (Superarray, Frederick, MD, www.superarray.com) and used with the ReactionReady™ HotStart PCR master mix (including an internal normalizer) following the manufacture's instructions. The resultant PCR products were resolved on 2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

Intracellular calcium (Ca2+) measurements

We used the calcium indicator fluo-3/AM to measure intracellular Ca2+ transients in iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes as described before (18). Briefly, iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes were cultured on gelatin-coated 35 mm MatTek glass-bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, www.glass-bottom-dishes.com). Cells were incubated for 20 minutes in 30 μmol/L fluo-3/AM and 0.02% (wt/wt) Pluronic F-127 (both Molecular Probes) in modified Tyrode's solution containing (in mmol/l): 136 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 1.8 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 0.5 probenecid (pH 7.4). Cells were then washed three times for 5 minutes each in indicator-free Tyrode's solution, which was also the standard bath solution for Ca2+ imaging. The fluo-3/AM-loaded cells were paced externally using a Grass S9 stimulator (Grass-Telefactor, West Warwick, RI, www.grasstechnologies.com) and bipolar platinum electrodes immersed in the bath. Ca2+ transients of fluo-3/AM loaded cells were measured by rapid line-scan confocal microscopy using a Zeiss Pascal 5 laser scanning confocal microscope fitted with a 40× (1.2 NA) water immersion objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc.). Line scans were performed at 2 ms/line, with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of >505 nm. Background fluorescence of unloaded cells was negligible. Image analysis was performed using custom software programmed in IDL 6.1 (ITT, Boulder, CO, www.rsinc.com).

Smooth muscle and endothelial cell functionality assays

To assess cell functionality, SMC contractility, uptake of acLDL in EC, and Matrigel EC in vitro tube formation were determined as described previously (12, 19, 20). A detailed description of the assays can be found in the supplemental data file. To serve as controls, primary murine vascular smooth muscle cells (mSMC), isolated from thoracic aortas of C57BL/6 mice, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), obtained from Lonza, were cultured in either SMGM-2 or EGM-2 media (Lonza).

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test or ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparison test. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Results

iPS cells contribute in vivo to cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages

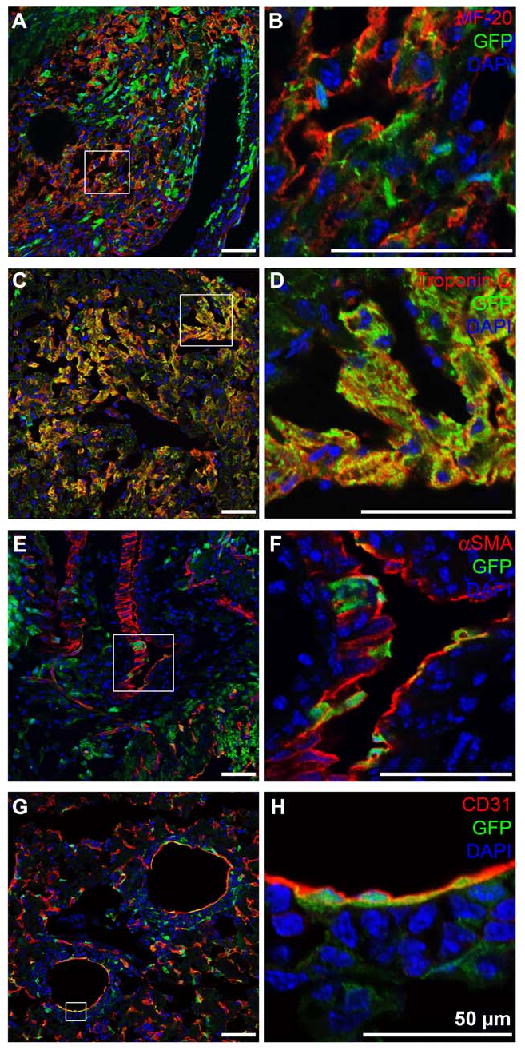

It has been previously reported that murine 2D4 iPS cells carrying a GFP transgene in the ubiquitiously expressed R26 locus (Suppl. Fig. 1), upon blastocyst injection, give rise to viable high-degree newborn chimeras with contribution to multiple tissues including the heart (4), although the exact cardiovascular cell types were not identified. To determine if GFP-labeled 2D4 iPS cells contribute in vivo to all cell types of the cardiovascular lineage, we surveyed sections from the 2D4 iPS cell-derived chimeric mice (4) for expression of known cardiac (sarcomeric myosin heavy chain (MF-20) and troponin C), smooth muscle (αSMA) and endothelial (CD31) markers. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrated that GFP-expressing 2D4 iPS cells had the capacity to differentiate in vivo into mature cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1A-D); vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 1E, F) and endothelial cells (Fig. 1G, H) (Suppl. Fig. 2). In addition, in the previous study it was shown that between 18% and 28% of hematopoietic cells isolated from the spleen and thymus of newborn 2D4 iPS cell-derived chimeric mice were derived from iPS cells (4).

Fig. 1. In vivo differentiation potential of murine iPS cells.

Immunohistochemical double staining of heart sections of newborn 2D4 iPS cell-derived chimera mice shows that GFP-expressing iPS cells (green) contribute to cells of the cardiovascular lineage including cardiomyocytes: (A, B) MF-20 (red), (C, D) Troponin C (red); smooth muscle cells: (E, F) αSMA (red); and endothelial cells: (G, H) CD31 (red). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 50 μm.

ES and iPS cell-derived EBs express markers of early mesodermal, cardiovascular and hematopoietic cells

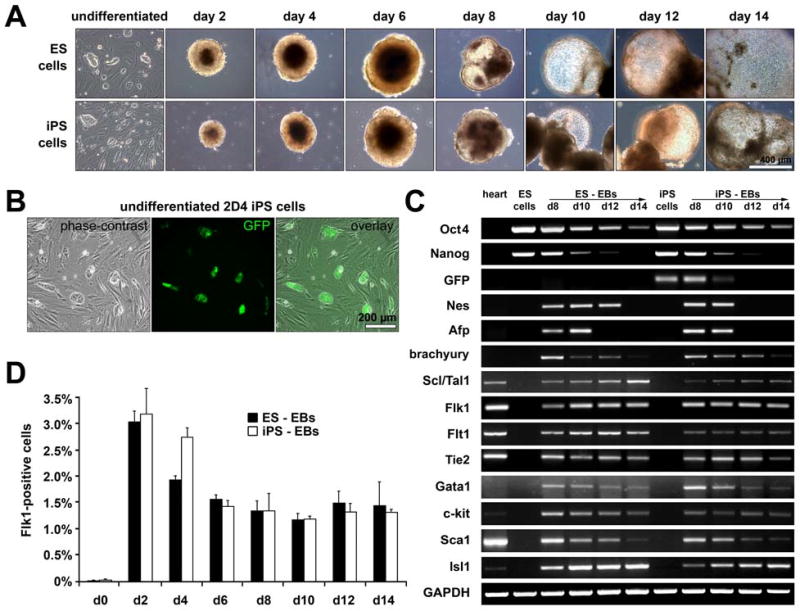

Murine ES cells have been shown to be able to differentiate into cell lineages of all three embryonic germ layers: mesoderm, endoderm, and ectoderm when allowed to aggregate in suspension and from three-dimensional (3D) colonies known as embryoid bodies (21). To characterize the differentiation potential of iPS cells, EBs were formed from both D3 ES and 2D4 iPS cells. ES and iPS cells exhibited comparable EB growth characteristics with similar 3D morphology, although 2D4 iPS cell-derived EBs were initially (day 2 and 4 of EB culture) smaller in size when compared to D3 ES cell-derived EBs (Fig. 2A; Suppl. Table 2). Gene expression profiling of developing ES and iPS cell-derived EBs demonstrated down-regulated expression of markers of undifferentiated ES and iPS cells including Oct4, Nanog and GFP (undifferentiated iPS cells only; Fig. 2B); accompanied by an upregulation of the ectoderm marker nestin (Nes), the endoderm marker α-fetoprotein (Afp), as well as mesodermal genes including brachyury, T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 (Scl/Tal1), Flk1, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt1), endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase (Tie2), GATA binding protein 1 (Gata1), c-kit, lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus A (Sca1/Ly6a), ISL1 transcription factor, LIM/homeodomain (Isl1); all of which have been reported to be mesodermal progenitor cell markers (17, 22) (Fig. 2C). FACS analysis demonstrated the presence of a Flk1-positive cell population in both ES and iPS cell-derived EBs, with highest expression levels between day 2 and day 4 (day 2: 3.06 ± 0.21% and 3.21 ± 0.49%; day 4: 1.95 ± 0.08% and 2.77 ± 0.18%) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. EB formation and differentiation profiles of murine ES and iPS cells.

(A) Phase-contrast images show comparable growth characteristics of D3 ES and 2D4 iPS cell-derived EBs. Scale bar equals 400 μm. (B) Nanog promoter-driven GFP expression in undifferentiated 2D4 iPS cells grown on MEF. Scale bar equals 200 μm. (C) RT-PCR analysis showing the downregulation of markers of undifferentiated ES and iPS cells including Oct4, Nanog and GFP, as well as upregulation of ectodermal, endodermal and mesodermal genes. (D) FACS analysis reveals the presence of Flk1-positive progenitor cells within ES and iPS cell-derived EB cultures.

To further characterize the heterogeneous cell phenotypes present in ES and iPS cell-derived EBs, we examined total mRNA for cardiac, smooth muscle, endothelial and hematopoietic markers using semi-quantitative RT-PCR (Suppl. Fig. 3). There was comparable expression of cardiomyocyte-associated transcription factors [Nkx2.5; GATA binding protein 4 (Gata4); myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2c); T-box 5 (Tbx5)] and genes [α-myosin heavy chain (αMHC); β-myosin heavy chain (βMHC); myosin, light polypeptide 7, regulatory (Mlc2a); myosin, light polypeptide 2, regulatory, cardiac, slow (Mlc2v); natriuretic peptide precursor type A (Nppa)] in D3 ES and 2D4 iPS cell-derived EBs during differentiation (Suppl. Fig. 3A). Similar to ES cell-derived EBs, we found spontaneously beating iPS cell-derived EBs starting as early as day 10 (supplemental online video 1 (ES cell-derived EB) and 2 (iPS cell-derived EB)).

Likewise, SMC and EC-associated gene expression patterns were seen in both ES and iPS cell-derived EBs (Suppl. Fig. 3B and C). Expression of Acta2; myocardin-related transcription factor a (Mrtf-a); myocardin-related transcription factor b (Mrtf-b); and Cald1 increased progressively in both ES and iPS cell-derived EBs (Suppl. Fig. 3B). Endothelial lineage-related genes including Pecam1 (CD31); Cdh5 (CD144/VE-Cadherin); ephrin-B2 (Ephb2) (expressed predominantly on arterial EC (23)); and ephrin-B4 (Ephb4) (expressed predominantly on venous EC (24)) were comparably expressed in ES and iPS cell-derived EBs (Suppl. Fig. 3C). Similarily, the expression pattern of hematopoietic-associated markers including homeobox protein B4 (Hoxb4), runt related transcription factor 1 (Runx1); Notch gene homolog 1 (Notch1); transcription factor PU.1 (PU.1); core-binding factor, runt domain, alpha subunit 2, translocated to, 3 (Eto2/Cbfa2t3); and LIM domain only 2 (Lmo2) was indistinguishable between ES and iPS cell-derived EBs (Suppl. Fig. 3D). Taken together, D3 ES and 2D4 iPS cells exhibited a similar EB-forming ability and a comparable EB-induced cardiovascular and hematopoietic differentiation potential as measured by cell type-associated gene expression.

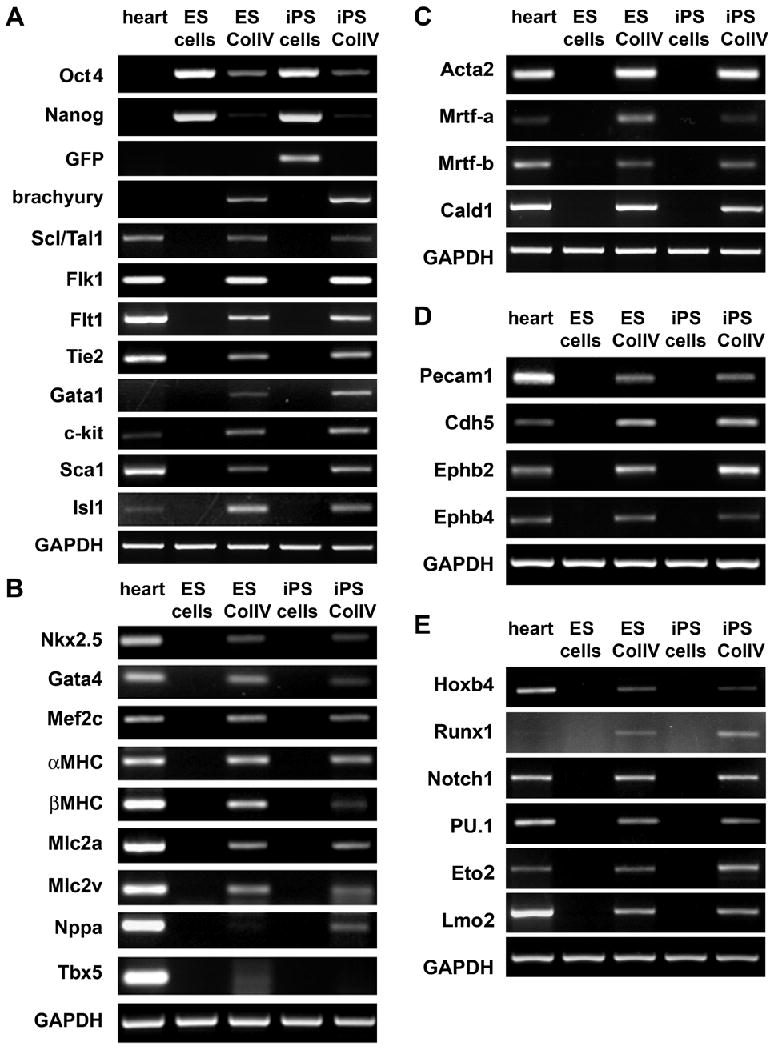

ColIV induces cardiovascular and hematopoietic differentiation of ES and iPS cells

It has been recently demonstrated by us and others that culturing ES cells on collagen type IV is a simple in vitro system to differentiate these cells toward the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages (10-13). To determine if iPS cells have a similar differentiation potential we cultured undifferentiated iPS cells for 4 days on ColIV. Similar to results seen in ColIV-differentiated ES cell cultures, ColIV-exposed iPS cells expressed mesodermal progenitor cell markers (Fig. 3A). FACS analysis revealed the presence of Flk1-expressing progenitor cells in both, ColIV-differentiated ES and iPS cells (2.2 ± 0.7% and 10.4 ± 1.4%). Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis confirmed the presence of cardiac (Fig. 3B), vascular smooth muscle and endothelial (Fig. 3C and D), as well as hematopoietic-associated genes (Fig. 3E) within the heterogeneous population of ColIV-differentiated ES and iPS cells.

Fig. 3. ColIV induces expression of early mesodermal, cardiovascular and hematopoietic genes.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR shows that ColIV-differentiated ES and iPS cells express markers of (A) mesodermal progenitor cells, (B) cardiomyocytes and cells of the (C) smooth muscle, (D) endothelial and (E) hematopoietic lineages.

iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes, SMC, EC and hematopoietic cells

To determine if ColIV-differentiated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells had the capacity to differentiate into cardiovascular cells, we isolated the Flk1-expressing cells and cultured them in media for cardiac, smooth muscle and endothelial differentiation. Gene expression analysis of isolated undifferentiated Flk1-positive cells revealed the presence of genes associated with cardiovascular progenitor cells including brachyury, Flk1, c-kit and Nkx2.5, whereas no markers of differentiated cardiovascular cells were expressed (Suppl. Fig. 4) (15-17, 25). However, when cultured in differentiation-promoting conditions, Flk1-positive cells differentiated into mature cardiovascular cells as shown by the increased expression of cardiac, SMC and EC markers, accompanied by the concomitant decrease in expression of stem and progenitor cell genes (Suppl. Fig. 4).

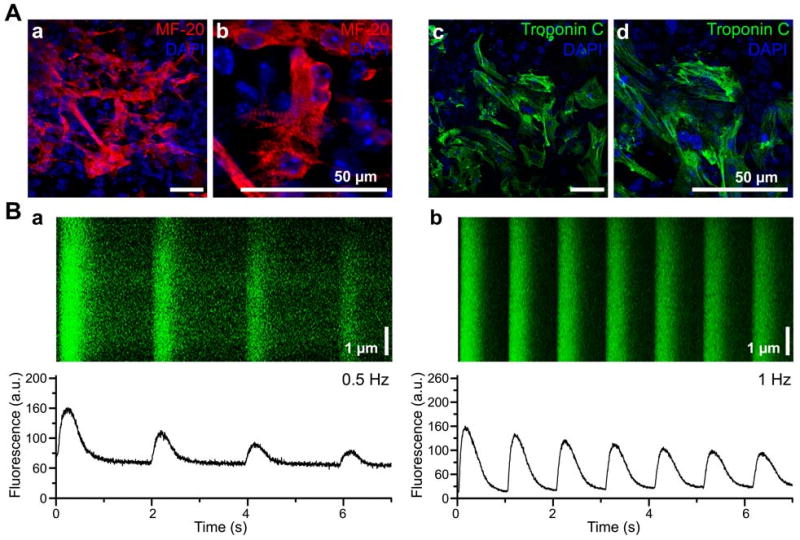

Flk1-positive cells differentiated in conditions to promote cardiac differentiation developed spontaneously beating cell clusters after 10-12 days of culture (supplemental online video 3). Immunocytochemical staining of the spontaneously beating areas revealed the presence of cardiomyocytes with typical cross-striation that expressed cardiac markers including sarcomeric myosin (MF-20) (Fig. 4A; a and b) and Troponin C (Fig. 4A; c and d). Furthermore, iPS cell-derived cardiomyocytes loaded with the calcium indicator fluo-3/AM could be externally paced at frequencies of 0.5 Hz (Fig. 4B, a) and 1 Hz (Fig. 4B, b) generating characteristic Ca2+ transients.

Fig. 4. iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells differentiate into functional cardiomyocytes.

(A) iPS cell-derived ColIV-differentiated Flk1-positive progenitor cells differentiate into (a, b) sarcomeric myosin (red; MF-20 staining) and (c, d) Troponin C (green) expressing cardiomyocytes. Cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars equal 50 μm. (B) Linescan images (upper panels) and spatially averaged fluorescence transients (lower panels) from a single iPS cell-derived cardiomyocyte loaded with the Ca2+ indicator fluo-3/AM. Transients were evoked by pacing with platinum electrodes at a frequency of (a) 0.5 Hz and (b) 1 Hz. The spatially synchronous onset of each transient and the rapid upstroke of spatially averaged fluorescence traces indicate electrically triggered Ca2+ release. Fluorescence intensities are displayed in arbitrary units (a.u.). Scale bars equal 1 μm.

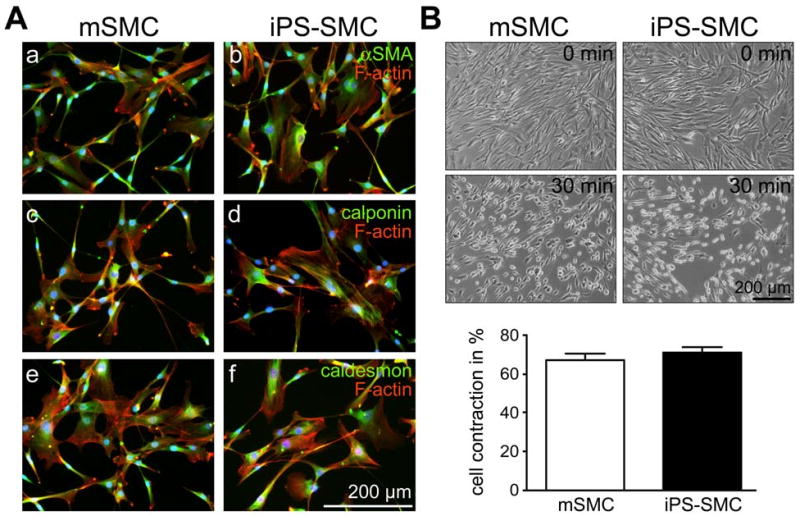

Similar to ColIV-differentiated ES cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors (11), the majority of the iPS cell-derived Flk1-expressing cells, cultured in PDFG-BB medium, differentiated into cells that expressed αSMA, calponin and caldesmon (Fig. 5A). To assess their functional capacity, mSMC and iPS cell-derived SMC (iPS-SMC) were exposed to carbachol for 30 minutes. Both cell types showed similar contraction patterns (cell contraction 66.9 ± 3.4% (mSMC) and 71.1 ± 2.4% (iPS-SMC); p=0.16) (Fig. 5B; Suppl. Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. In vitro SMC differentiation potential of iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors.

(A) Immunocytochemical staining shows comparable expression of (a, b) αSMA (green), (c, d) calponin (green) and (e, f) caldesmon (green) in mSMC and iPS-SMC. F-actin staining visualizes the cell cytoskeleton (red). Cell nuclei are shown with DAPI (blue). Scale bar equals 200 μm. (B) mSMC as well as iPS cell-derived SMC contract after 30 minutes exposure to 10-5 M carbachol. Scale bar equals 200 μm.

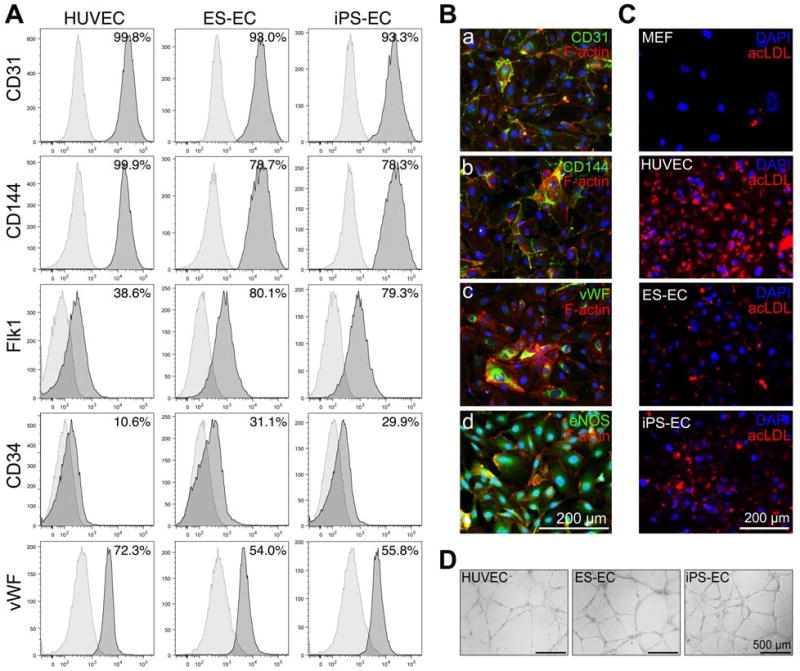

When treated with VEGF, ES and iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors differentiated into cells that expressed EC-associated markers including CD31, CD144, Flk1, CD34, vWF and eNOS (Fig. 6A and B), and exhibited a comparable EC-typical cobblestone morphology (Suppl. Fig. 6). FACS analysis revealed that ES cell-derived EC (ES-EC) and iPS cell-derived EC (iPS-EC) exhibited similar EC marker expression; however, when compared to mature human EC (HUVEC), both ES-EC and iPS-EC displayed slightly different cell surface maker expression profiles (HUVEC versus ES-EC and iPS-EC: CD31: 99.8 ± 1.2% versus 93.0 ± 3.5% and 93.3 ± 4.4%; CD144: 99.9 ± 2.1% versus 78.7 ± 5.5% and 78.3 ± 5.1%; Flk1: 38.6 ± 3.2% versus 80.1 ± 4.9% and 79.3 ± 4.6%; CD34: 10.6 ± 4.9% versus 31.1 ± 5.1% and 29.9 ± 3.1%; vWF: 72.3 ± 1.8% versus 54.0 ± 2.1% and 55.8 ± 2.8%) (Fig. 6A). ES-EC and iPS-EC but not MEF showed the ability to uptake acetylated low-density lipoprotein. However, when compared to HUVEC, ES-EC and iPS-EC incorporated lower amounts of acLDL (Fig. 6C; Suppl. Fig. 6); a phenomenon, which had previously been reported in ES-EC (20). Although ES-EC and iPS-EC exhibited different acLDL uptake when compared to mature human EC (HUVEC), they showed a similar in vitro tube forming behavior when seeded on Matrigel for 24 hours, suggesting a comparable angiogenic potential (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6. ES and iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells differentiate into functional EC.

(A) Phenotypic analysis of HUVEC, ES cell-derived EC (ES-EC) and iPS cell-derived EC (iPS-EC). (B) Immunocytochemistry shows expression of endothelial cell-associated markers including (a) CD31, (b) CD144, (c) vWF and (d) eNOS (all green) in iPS-EC. F-actin stains the cell cytoskeleton (red). Cell nuclei are shown with DAPI (blue). Scale bar equals 200 μm. (C) In contrast to MEF, HUVEC, ES-EC and iPS-EC have the ability to uptake acLDL (red). Cell nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar equals 200 μm. (D) HUVEC, ES-EC and iPS-EC form comparable capillary-like structures when cultured on Matrigel for 24 hours. Bars equal 500 μm.

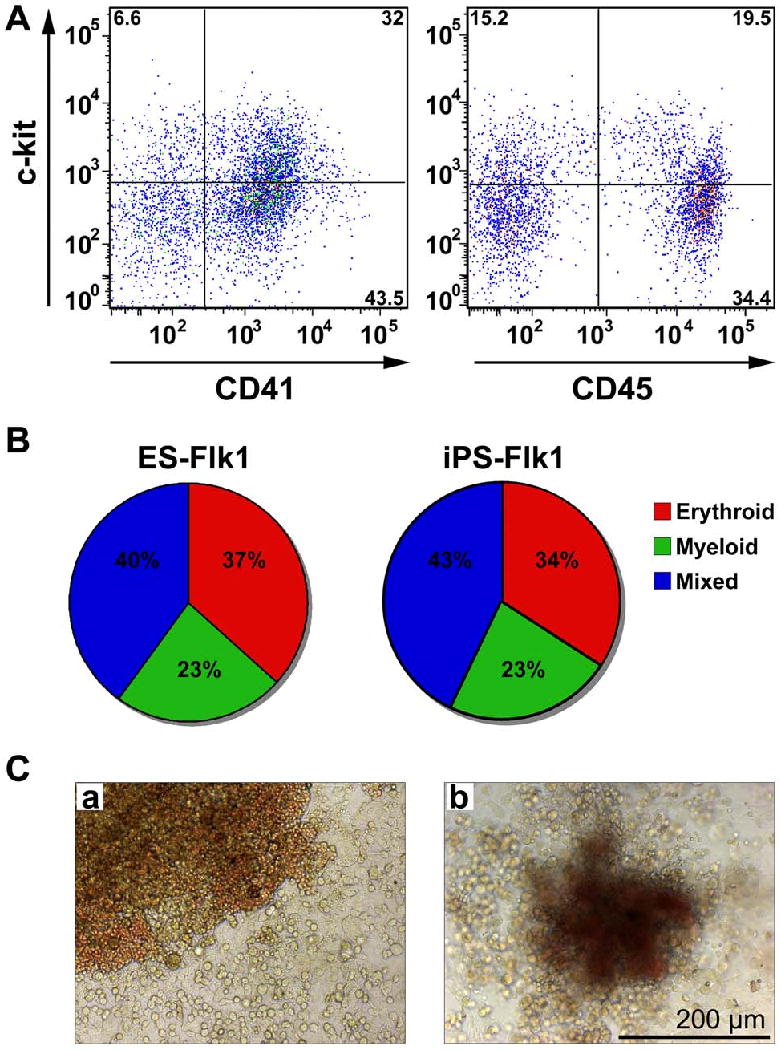

To define the hematopoietic differentiation potential, iPS cell-derived Flk1-progenitor cells were co-cultured on OP9-GFP stromal cells in media supplemented with hematopoietic cytokines. After 5-7 days of co-culture, cells were harvested and analyzed for cell surface antigen expression by flow cytometry. Cells expressing both c-kit and CD41, which identifies nascent hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells were seen (Fig. 7A) (26). A subset of the cells expressed the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 (Fig. 7A). After OP9-GFP co-culture, cells were also plated in methylcellulose to determine the myelo-erythroid differentiation potential. The iPS cell-derived Flk1-progenitor cells, like ES cells, had similar frequency of clonogenic progenitors (30 total CFUs/20,000 ES cell-derived Flk1-positive cells versus 35 total CFUs/20,000 iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive cells) and demonstrated equivalent differentiation potential into erythroid, myeloid and mixed colonies (Fig. 7B and 7C).

Fig. 7. Hematopoietic differentiation potential of iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells.

(A) FACS analysis of c-kit and CD41, as well as c-kit and CD45 on iPS cell-derived Flk1-progenitor cells grown on OP9 stroma for 5 days. (B) Pie charts depicting the variety of different hematopoietic colonies produced from both ES cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors (ES-Flk1) and iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors (iPS-Flk1) in methylcellulose. (C) Representative images of mixed colonies derived from (a) ES and (b) iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitors. Scale bar equals 200 μm.

Discussion

The potential of ES cells, which have the capacity to differentiate into all somatic cell types, has attracted much interest in the field of regenerative medicine and has been a topic of intense research in recent years (27). However, major obstacles to a successful clinical use of ES cell derivatives for tissue repair exist, including the immunological intolerance to allogeneic cells that can lead to rejection of mismatched cellular grafts and ethical concerns surrounding their use. In this study, we determined the cardiovascular and hematopoietic differentiation potential of murine iPS cells. Overall, only minor differences were seen in the growth and differentiation potential of 2D4 iPS cells when compared to D3 ES cells. We observed that 2D4 iPS cells reproducibly formed spherical EBs with growth characteristics and gene expression profiles similar to D3 ES cell-derived EBs. When exposed to ColIV, ES and iPS cells differentiated into cells that showed expression of genes associated with early mesodermal, cardiovascular and hematopoietic cells.

A cell capable of differentiating into all cardiovascular cell types has a theoretical advantage for more complete tissue regeneration over transplanting cardiomyocytes alone as has been currently demonstrated for ES cell derivatives (27). Conversely, partially differentiated cardiovascular progenitor cells, such as the Flk1-positive cells described here, will likely reduce the tumor formation seen when transplanting undifferentiated ES cells into the heart (28). To this end, we were able to identify Flk1-positive progenitor cells in both iPS cell-derived EBs and ColIV-differentiated iPS cells, most likely representing a population of multipotent mesodermal progenitor cells (15-17, 29). To confirm that those Flk1-expressing cells were capable of generating all cardiovascular cell types, we isolated ColIV-differentiated Flk1-positive cells and exposed them to cardiac, smooth muscle and endothelial cell-specific differentiation conditions. This resulted in the production of spontaneously beating cell clusters and cells expressing cardiac markers as well as hallmark morphological characteristics of mature cardiomyocytes including the typical cross-striation and generation of Ca2+ transients. Gene expression analysis, immunocytochemistry, contractility and in vitro tube formation assays, as well as acLDL uptake tests further revealed the successful differentiation of iPS cell-derived Flk1-progenitor cells into functional SMC and EC, findings that were similar to those previously reported for murine ES cells (10-12). Although iPS cells contributed to mature cardiovascular cells in vivo as well, it will be important to determine in future experiments if transplanted iPS cells can also integrate and differentiate into adult myocardium. In addition, co-culture of the Flk1-positive cells with OP9-GFP stromal cells in hematopoietic cytokine-containing culture medium confered differentiation into hematopoietic progenitor cells that expressed c-kit, CD41 and the pan-hematopoietic marker CD45 (26). Furthermore, these ES and iPS cell-derived hematopoietic progenitors demonstrated a multilineage myelo-erythroid differentiation potential.

Although ColIV-differentiated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells had properties comparable to the ES cell-derived progenitors previously described, differences did exist (11, 12, 15-17). Flk1-positive progenitor cells isolated from the ColIV-exposed cultures also possessed hematopoietic differentiation potential when cultured on OP9 stromal cells or in methylcellulose. As well, Flk1-positive cells were more frequent in ColIV-differentiated iPS cell cultures when compared to ES cell cultures; but whether this is a general property of iPS cells versus being specific to the 2D4 iPS cell line will require further study and comparison of multiple lines. Nonetheless, the first successful therapeutic application of murine iPS cells to correct a mouse model of sickle cell anemia has been reported (30). However, this required transducing the iPS cells with HoxB4 to generate engraftable hematopoietic stem cells. Thus an autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell would have significant therapeutic advantage if these ColIV-differentiated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells could produce engraftable hematopoietic stem cells, which we are currently investigating.

Despite the similarities in growth and differentiation of ES and iPS cells, some issues remain with regards to the clinical translation of the population of iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells. Is there one cell within the Flk1-positive progenitor cell population that is capable of differentiating into either cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineage or do these cells come from subpopulations with preferential mesodermal fates as has been suggested in the EB system (15)? Most importantly, whether a similar population can be isolated from human iPS cells is unknown at this time. Regardless of these uncertainties, direct reprogramming of somatic cells to generate patient-matched pluripotent stem cells has the potential to address many of the current limitations and could revolutionize the treatment of many diseases. The development of efficient, reliable and easily reproducible differentiation protocols for generating human iPS cell-derived cardiovascular and hematopoietic progenitor cells will facilitate the development of patient-tailored cardiovascular and hematopoietic regenerative therapies.

Summary

Reprogrammed murine fibroblasts exhibit comparable growth and differentiation characteristics when compared to murine ES cells. Given the appropriate extracellular signals, murine iPS cells differentiate with high efficiency into multipotent mesodermal progenitor cells that possess the potential to differentiate into functional cells of the cardiovascular and hematopoietic lineages. Ease of generation and lack of immunologic and ethical restrictions will likely make iPS cells a highly valuable cell source for applications in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

Suppl. Fig. 1 Generation of 2D4 iPS cells.

Suppl. Fig. 2In vivo developmental potential of 2D4 iPS cells. Immunofluorescence staining shows GFP-expressing 2D4 iPS cells (green) that contribute in vivo to cells of the cardiovascular lineage including cardiomyocytes (sarcomeric myosin (MF-20) and Troponin C staining (red)), smooth muscle cells (αSMA staining (red)), and endothelial cells (CD31 staining (red)). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 50 μm.

Suppl. Fig. 3 Cardiovascular and hematopoietic gene expression in ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis shows the upregulation of (A) cardiac, (B) smooth muscle, (C) endothelial and (D) hematopoietic cell markers.

Suppl. Fig. 4 RT-PCR analysis shows mRNA expression profiles of heart tissue, undifferentiated iPS cells, MACS-isolated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells, and differentiated Flk1-positive cells after 12 days of culture in alpha-MEM, PDFG-BB and VEGF medium (pooled samples).

Suppl. Fig. 5 After exposure to 10-5 M carbachol for 30 minutes, mSMC and iPS-SMC contracted between 66.9 ± 3.4% and 71.1 ± 2.4%. Scale bar equals 200 μm.

Suppl. Fig. 6 In contrast to murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), ES cell-derived EC (ES-EC) and iPS cell-derived EC (iPS-EC) display a typical cobblestone morphology and have the ability to uptake acetylated low-density lipoprotein (acLDL; red). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 100 μm.

Supplemental Table 1. Primer sets used for RT-PCR.

*DNA sequence for this gene was obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The PCR primers were designed using OligoPerfect™ Designer (Invitrogen).

Supplemental Table 2. Morphometric analysis of ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. The cross-sectional area was measured for at least 50 ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. For statistical analysis all data are presented as mean EB size in μm ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sam Chan, Scott Lamp and Peng Zhao for technical assistance, and Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker (University of Toronto, Canada) for providing the OP9-GFP cells. This work was supported by gifts from the Laubisch Fund (WRM) and a NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein grant (5T32HL007895-10) to KSL, a NIH Ruth L. Kirchstein National Research Service Award (GM07185) to KER, as well as grants P01 HL080111 and R01 HL62448 to WRM.

Footnotes

Author contribution summary: Katja Schenke-Layland: Collection and assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

Katrin E. Rhodes: Collection and assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

Ekaterini Angelis: Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript

Yekaterina Butylkova: Collection of data, Data analysis, Final approval of manuscript

Sepideh Heydarkhan-Hagvall: Provision of study material, Final approval of manuscript

Christos Gekas: Collection and assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript

Rui Zhang: Collection and assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Final approval of manuscript

Joshua I. Goldhaber: Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

Hanna K. Mikkola: Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

Kathrin Plath: Collection and assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Provision of study material, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

W. Robb MacLellan: Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Financial support, Final approval of manuscript

References

- 1.Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, et al. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature. 1997;385:810–813. doi: 10.1038/385810a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Nuclear reprogramming and pluripotency. Nature. 2006;441:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/nature04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maherali N, Shridharan R, Xie W, et al. Directly reprogrammed fibroblasts show global epigenetic remodeling and widespread tissue contribution. Cell Stem Cells. 2007;1:55–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Somatic Cells. Science. 2007 Nov 20; doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishikawa SI, Nishikawa S, Hirashima M, et al. Progressive lineage analysis by cell sorting and culture identifies FLK1+VE-cadherin+ cells at a diverging point of endothelial and hemopoietic lineages. Development. 1998;125:1747–1757. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita J, Itoh H, Hirashima M, et al. Flk1-positive cells derived from embryonic stem cells serve as vascular progenitors. Nature. 2000;408:92–96. doi: 10.1038/35040568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCloskey KE, Stice SL, Nerem RM. In vitro derivation and expansion of endothelial cells from embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;330:287–301. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-036-7:287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schenke-Layland K, Angelis E, Rhodes KE, et al. Collagen IV induces trophoectoderm differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1529–1538. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerecht-Nir S, Ziskind A, Cohen S, et al. Human embryonic stem cells as an in vitro model for human vascular development and the induction of vascular differentiation. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1811–1820. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000106502.41391.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kattman SJ, Huber TL, Keller GM. Multipotent flk-1+ cardiovascular progenitor cells give rise to the cardiomyocyte, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle lineages. Dev Cell. 2006;11:723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu SM, Fujiwara Y, Cibulsky SM, et al. Developmental origin of a bipotential myocardial and smooth muscle cell precursor in the mammalian heart. Cell. 2006;127:1137–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, et al. Multipotent embryonic Isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson SA, Goldhaber JI, So JM, et al. Functional adult myocardium in the absence of Na+-Ca2+ exchange: cardiac-specific knockout of NCX1. Circ Res. 2004;95(6):604–611. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000142316.08250.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira LS, Gerecht S, Shieh HF, et al. Vascular progenitor cells isolated from human embryonic stem cells give rise to endothelial and smooth muscle like cells and form vascular networks in vivo. Circ Res. 2007;101(3):286–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.150201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCloskey KE, Smith DA, Jo H, et al. Em Embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells may lack complete functional maturation in vitro. J Vasc Res. 2006;43(5):411–421. doi: 10.1159/000094791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller G. Embryonic stem cell differentiation: emergence of a new era in biology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1129–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gläsker S, Li J, Xia JB, et al. Hemangioblastomas share protein expression with embryonal hemangioblast progenitor cell. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4167–4172. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XQ, Takakura N, Oike Y, et al. Stromal cells expressing ephrin-B2 promote the growth and sprouting of ephrin-B2(+) endothelial cells. Blood. 2001;98:1028–1037. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang XQ, Takakura N, Oike Y, et al. Stromal cells expressing ephrin-B2 promote the growth and sprouting of ephrin-B2(+) endothelial cells. Blood. 2001;98:1028–1037. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torella D, Ellison GM, Nadal-Ginard B, et al. Cardiac stem and progenitor cell biology for regenerative medicine. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mikkola HK, Orkin SH. The journey of developing hematopoietic stem cells. Development. 2006;133(19):3733–3744. doi: 10.1242/dev.02568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dai W, Kloner RA. Myocardial regeneration by embryonic stem cell transplantation: present and future trends. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2006;4(3):375–383. doi: 10.1586/14779072.4.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behfar A, Perez-Terzic C, Faustino RS, et al. Cardiopoietic programming of embryonic stem cells for tumor-free heart repair. J Exp Med. 2007;204:405–420. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park C, Ma YD, Choi K. Evidence for the hemangioblast. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:965–970. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, et al. Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin. Science. 2007;318:1920–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1152092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suppl. Fig. 1 Generation of 2D4 iPS cells.

Suppl. Fig. 2In vivo developmental potential of 2D4 iPS cells. Immunofluorescence staining shows GFP-expressing 2D4 iPS cells (green) that contribute in vivo to cells of the cardiovascular lineage including cardiomyocytes (sarcomeric myosin (MF-20) and Troponin C staining (red)), smooth muscle cells (αSMA staining (red)), and endothelial cells (CD31 staining (red)). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 50 μm.

Suppl. Fig. 3 Cardiovascular and hematopoietic gene expression in ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis shows the upregulation of (A) cardiac, (B) smooth muscle, (C) endothelial and (D) hematopoietic cell markers.

Suppl. Fig. 4 RT-PCR analysis shows mRNA expression profiles of heart tissue, undifferentiated iPS cells, MACS-isolated iPS cell-derived Flk1-positive progenitor cells, and differentiated Flk1-positive cells after 12 days of culture in alpha-MEM, PDFG-BB and VEGF medium (pooled samples).

Suppl. Fig. 5 After exposure to 10-5 M carbachol for 30 minutes, mSMC and iPS-SMC contracted between 66.9 ± 3.4% and 71.1 ± 2.4%. Scale bar equals 200 μm.

Suppl. Fig. 6 In contrast to murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), ES cell-derived EC (ES-EC) and iPS cell-derived EC (iPS-EC) display a typical cobblestone morphology and have the ability to uptake acetylated low-density lipoprotein (acLDL; red). DAPI-staining was performed to show cell nuclei (blue). Scale bars equal 100 μm.

Supplemental Table 1. Primer sets used for RT-PCR.

*DNA sequence for this gene was obtained from the GenBank database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The PCR primers were designed using OligoPerfect™ Designer (Invitrogen).

Supplemental Table 2. Morphometric analysis of ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. The cross-sectional area was measured for at least 50 ES and iPS cell-derived EBs. For statistical analysis all data are presented as mean EB size in μm ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t test. P-values less than 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.