Abstract

An important component of end-of-life education is to provide health professionals with content related to dying, loss, and grief. The authors describe the strategies used to develop and offer a blended course (integration of classroom face-to-face learning with online learning) that addressed the sensitive and often emotional content associated with grieving and bereavement. Using Kolb’s experiential learning theory, a set of 4 online learning modules, with engaging, interactive elements, was created. Course evaluations demonstrated the success of the blended course in comparison to the traditional, exclusive face-to-face approach.

The U.S. health care system often fails to provide appropriate care to people of all ages who face the end-of-life transition. For example, surprisingly, more than half of the people dying of cancer do so with their pain unrelieved and their expressed wishes for life-sustaining treatments not honored (1). An enormous need exists to help persons of all ages and their families through the myriad of physical, psychosocial, spiritual, and economic changes while supporting them in making complex and difficult ethical decisions consistent with their preferences for end-of-life care.

Despite these alarming statistics, the education of health professionals in palliative and end-of-life care is fairly recent. To address this gap in nursing education and clinical practice, several programs for end-of-life education have been developed and offered at the national level, including the Toolkit for Nurturing Excellence at the End of Life-Nurse Educators (TNEEL-NE) (2), the programs within End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) (3), the Education for Physicians on End-of-life Care (EPEC) Curriculum (4), the Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care (IPPC) (ippcweb.org), and the Harvard Medical School Program in Palliative Care Education and Practice (PCEP) (5). At a university level, we have addressed the gap by securing funding to develop the Advanced Practice Palliative Care Nurse (APPCN) program, as a new life span-oriented specialty concentration at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) College of Nursing preparing advanced practice nurses to serve newborns, children, adults, and elderly individuals.

One course in our APPCN curriculum focused on the social, cultural, and psychological aspects of human grief, loss, and death within families and professional caregivers as they engage in palliative and end-of-life care. In order to reach a larger geographical audience and create content appropriate for distance learning strategies, a blended course, defined as the integration of classroom face-to-face learning with online learning (6) was developed, with the majority of the content being offered online. We were challenged in using a mostly distant, non-personal medium for instruction because of the sensitive nature of the content dealing with dying, loss and grief.

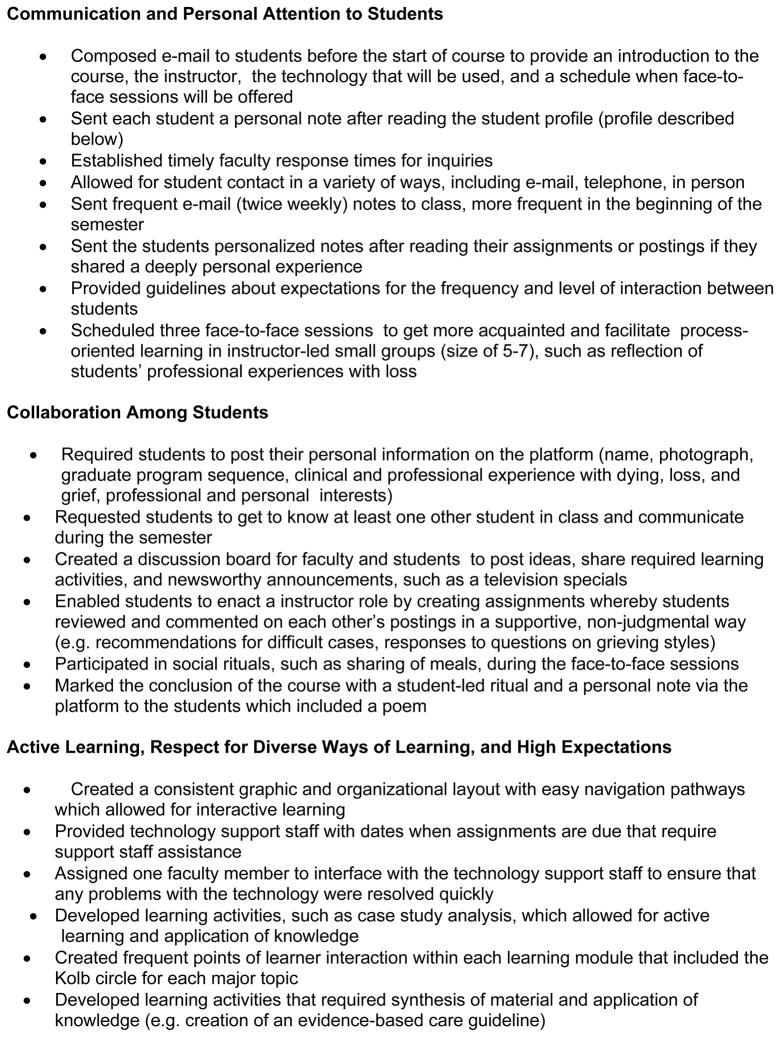

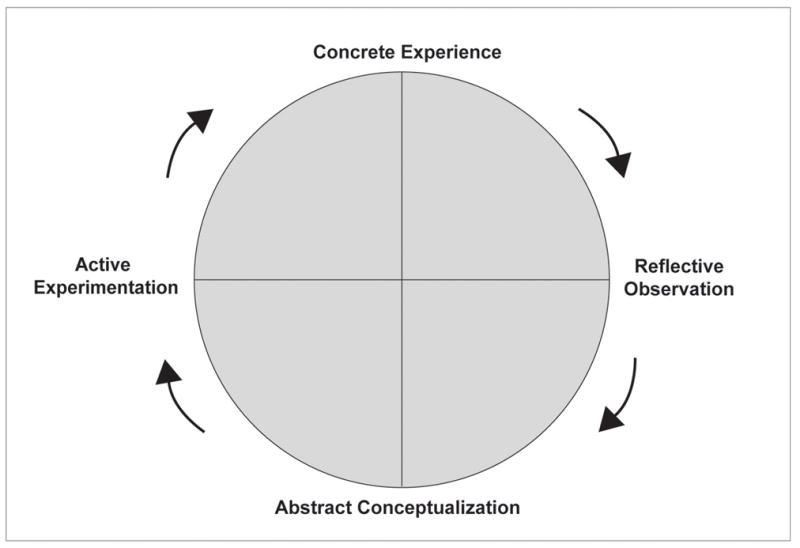

Kolb Experiential Learning Theory

Kolb’s (7) Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) served as the framework for 3 courses developed within the APPCN program. ELT evolved from Dewey’s philosophical pragmatism, Lewin’s social psychology, and Piaget’s cognitive-developmental genetic epistemology, which taken together form a unique perspective on learning and development (7) The ELT has been simplified by the concept of teaching around the circle, from which we created our learning circle model for teaching and learning in this course (Figure 1). In a simplified form, our learning circle model included 4 basic concepts from Kolb’s ELT (8):

Figure 1.

Learning Circle for Palliative Care Courses based on Kolb’s Experiential Learning Theory

Concrete experience: a video, audio or text-based case study or clinical practice simulation that will allow the learner to involve him/herself in a concrete experience

Reflective observation: reflection on the concrete experience from different perspectives (patient, the family members, health care professionals)

Abstract conceptualization: engagement in abstract conceptualizations about the different perspectives in order to recognize generalizations or principles of sound theories that integrate their observations and formulate a plan of care.

Active experimentation: using these generalizations or theories to apply the insights in new, more complex situations, which results in new concrete experiences from which to begin the circle again.

This around the circle method was used to create a self-study online set of learning modules with engaging, interactive elements that appealed to individuals with different styles of learning. This approach was especially well suited for our course on dying, loss, and grief because this approach incorporates experiential learning and reflective work, which are recommended for teaching in end-of-life care and death education (9, 10, 11).

Description of Course Content and Learning Activities

Course content was separated into 4 modules which were further divided into smaller “subtopics” (Table 1). The Kolb Experiential Learning Model served as the vehicle to guide learners through each module in an organized, predictable manner. This framework permitted faculty to incorporate a variety of teaching strategies. Creativity was promoted within the working group which allowed each educator to engage learners in ways that best suited their teaching style and the course material. Online learning provides educators a way to employ learning activities that are creative, collaborative, and stimulate critical thinking (12). An advantage to using the Kolb model was the ability for faculty to connect with students in a manner that appealed to their individual learning style and gave students the opportunity to engage in alternative learning methods as the Kolb framework differed greatly from that used in most other online courses in the College.

Table 1.

Description of Course Content and Learning Activities

| Module and Subtopics | Examples of Learning Activities in the Module | Face-to-Face Class Session for the Module |

|---|---|---|

| Online Pretest | ||

Personal and Professional Narratives of Dying, Loss and Grief

|

Online responses to questions about self-care strategies and posting of an initial plan to implement a strategy for institutional support of professionals in the clinical setting | Further acquaintance work fellow learners; viewing IPPC video on professionals’ coping with pediatric death followed by reflective work on professional experience with bereavement |

The Dying Trajectory and Near Death Experiences

|

Online posting of a case from clinical experience that portrayed the dying trajectory of a patient and subsequent responses to class mates’ postings with evidence-based recommendations for care | None |

Grief and Loss: Conceptual Dimensions

|

Online responses to questions about gender differences in grief Electronic submission of a review of a book that is based on a personal account of content related to the course (dying, loss and grief) Electronic submission of a paper which entailed a discussion of themes portrayed in art at a museum exhibit for “Day of the Dead” |

Two separate panel discussions: bereaved individuals and palliative care advanced practice nurses |

Facilitating Healing in Individuals and Families

|

Online responses to questions regarding research that examined efficacy of grief interventions Electronic submission of a paper which entailed the development or evaluation of an evidence-based care guideline related to course content |

Verbal presentation of development/evaluation of care guideline and closing ritual with community of learners |

| Online Post-test |

The Kolb learning circle began with viewing of a video, listening to an audio clip or reading poetry within the Concrete Experience, which we termed Human Experience, segment of the circle. The selected material served to focus on a particular issue or experience common to the specific content in the module. For example, for the second module on the dying trajectory and near death experiences, one video clip portrayed a mother with advanced illness during which she disclosed how the meaning of hope changed as her disease progressed. Using media that allowed students to hear and see actual patients and their significant others express their feelings and insight generated a much more powerful experience for the learners than simply reading the information in text format. The students were also provided with additional background and follow-up information on the patients seen in the videos, further humanizing the experience.

The students then progressed to the Reflective Observation portion of the circle. Here, they had the opportunity to contemplate the situation highlighted in Human Experience and reflect on their feelings by providing short answers to structured questions in text boxes, which were submitted directly into the online module. Due to the sensitive nature of the material and learners’ unique responses to loss experiences, any student who did not feel comfortable sharing their thoughts on a particular subject with faculty or classmates was not required to do so, but instead was encouraged to reflect on the questions through journaling in a separate document that was not shared with the instructor.

Abstract Conceptualization, which we renamed Theoretical Perspectives, the third portion of the circle, consisted of theory on dying, loss and grief drawn from a variety of sources such as textbooks, journal articles, materials from the national programs previously mentioned, and interviews with bereaved family members. Educators used a variety of teaching strategies to present the theoretical material: video and audio clips, narrated power points, web sites, case studies and accounts from real people. Electronic reserve, available through the University library, facilitated student access to readings, and enabled the faculty to easily update materials as needed.

The final segment of the learning circle, Active Experimentation, renamed Apply Knowledge, provided the learners with opportunities to extrapolate knowledge gained to new situations and to develop and share creative interventions with fellow learners. We created content-and process-oriented online discussion forms in threaded-message bulletin boards, which have been recommended to provide focus, discussion momentum, and allow the faculty to guide students in reactive learning (13). The asynchronous discussion which we employed allowed the learner time for reflection and preparation of responses (12). This process is helpful to students who are less verbal than some of their counterparts (12). The final project in this section was to develop or evaluate an evidence-based clinical resource which was shared with the other members of the class during the last class session. Most students chose to develop a resource, displaying astounding creativity and leadership skills which will undoubtedly benefit the palliative care arena.

Blended learning occurred using the online modules which were accessible via a password protected Internet site, Blackboard Academic Suite™ (an education platform) for communication among faculty and learners and resource sharing, and 3 face-to-face sessions. The decision to blend online learning with several face-to-face sessions was driven not only by the sensitive nature of the subject matter, but from previous experience with teaching the course in a traditional face-to-face format. Prior students gave feedback on course content, and it was evident that certain concepts required face-to-face interpersonal interaction to enhance understanding. One of the panel discussions, for example, provided insight into the private thoughts, feelings and experiences of bereaved individuals. The learners themselves also found personal interaction with classmates valuable, as they were able to share resources and knowledge with each other as they developed camaraderie.

Strategies for Successful Blended Learning

The strategies we used for creating a sensitively-delivered blended course were consistent with the seven principles for using technology for good practice in education (14). These principles include: encouragement of communication between students and faculty with personal attention to students, collaboration among students, active learning, respect for diverse talents and ways of learning, communication of high expectations, prompt feedback, and time on task (14). A summary of the strategies we used are summarized according to these principles in Figure 2. Many of these strategies are recommended by others for online learning (12, 13, 15). Our goal was to demonstrate faculty behaviors that showed sensitivity to course content while creating the course materials and environment for quality instruction.

Figure 2.

Strategies for Successful Blended Learning for Sensitive Course Content

Course Evaluation

At the end of the semester, students were requested to complete an evaluation of the course using the standard course evaluation form used for all courses in the college. This evaluation form is comprised of 13 evaluation items and an area for free text comments, and is submitted electronically by the students. The evaluations for this newly developed blended course are found in Table 2. For comparison, evaluation of the course from the traditional face-to-face approach (which was coordinated by the same faculty member) are included in the table. The free text comments were overwhelmingly positive. Common themes in these comments, such as the importance of communication and personal attention to students, reinforced the value of adhering to the principles for good teaching (14), particularly with sensitive course content. One student said, “The instructors provided thoughtful communication and prompt follow-up throughout the semester. Thanks to the activities and face-to-face interactions they successfully created a connection between students which is difficult to do with an online course. The level of this course was outstanding, and they (faculty) should be commended in making a wonderful transition for this material to an online format.” Only two students had suggestions for improvement; both recommendations centered around more opportunities for active learning.

Table 2.

Students’ Evaluations of Dying, Loss, and Grief

| Evaluation Item | NUSC 520 (Traditional face-to-face, Fall 2006) N = 10 | NUSC 520 (Blended, Fall 2007) N = 9 |

|---|---|---|

| COURSE EVALUATION | Mean rating (1 = disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | |

| The overall quality of the course was high. | 4.9 | 4.89 |

| The course objectives and expectations were clear. | 4.8 | 4.78 |

| The course content was relevant to the objectives. | 4.78 | 4.9 |

| The course materials were well-prepared. | 4.8 | 4.89 |

| The textbooks/required readings were useful. | 4.8 | 4.78 |

| Class assignments and learning activities were appropriate. | 4.8 | 4.89 |

| Evaluation methods were appropriate. | 4.8 | 4.78 |

| INSTRUCTOR EVALUATION | ||

| The overall quality of the instruction was high. | 4.9 | 4.89 |

| The instructor was knowledgeable about the subject matter. | 4.9 | 5.0 |

| The instructor’s presentations were well organized. | 4.7 | 4.78 |

| The instructor employed a variety of teaching/learning strategies. | 4.7 | 4.89 |

| The instructor treated students with respect. | 4.89 | 5.0 |

| The instructor was receptive to student concerns. | 4.78 | 4.89 |

In comparison to the course evaluations for the traditional approach, the evaluations for the blended version were close to or higher for all criteria. Faculty also had favorable experiences with the new version as course preparation allowed much self reflection and the implementation increased the mutual learning that occurred between faculty and student learners. In summary, the course was rated to be very successful despite initial hesitancy of students and some faculty regarding the online aspect for a course of this nature.

Resources Required for Course Development and Administration

Resources specific to each aspect of the course’s development need to be identified and acquired to develop and implement a course of this nature. Resources fall into several categories including faculty expertise and interest, technical support and programming skills, and online educational platforms appropriate to the course’s intended audience. For our APPCN courses, financial support was provided through a training grant. Although the availability of resources across educational institutions will vary, using internal resources is optimal. A dependence on outside or consulting resources increases the risks that technical and faculty support will not be available when needed. Ensuring that internal resources are adequate to maintain the online course platform increases the likelihood of success and learner satisfaction.

Faculty members participating in the grief blended course were committed to offering the course in a primarily online environment. For some faculty members, this commitment required they learn new methods to present and deliver the course content, such as developing narrated PowerPoint presentations, using film and other media, and developing content that appealed to a variety of learning styles. Using diverse delivery methods, including face-to-face meetings, required the teaching faculty to carefully consider the optimal delivery method specific to specific course content. These multiple decision points demanded more planning and flexibility from faculty, especially given the often-sensitive nature of the content and learning materials. Altogether, faculty teaching a course using blended methods and learning modalities designed to meet various learning styles need to be open to learning new skills, developing educational materials in a variety of formats, and being flexible in their approach to learning.

To further support development of online courses, a substantial amount of faculty time was allotted for the initial development of an online course and subsequent adjustments. Support for faculty time was provided during the summer to develop online courses. Teaching assistants were hired to develop graphic illustrations, to locate online resources to support courses, and to work with the Instructional Technology department to adapt the teaching materials to an online environment.

This course had previously been taught twice as a traditional face-to-face class. With the goal of converting the course to a blended format, class sessions were videotaped (with students’ and presenters’ permission) during the last semester it was offered in the face-to-face format. Excerpts were taken from various class sessions and used as video clips for the blended course. This gave the future students the ability to see other students’ comments on and reactions to various topics. Additionally, at the end of each class session and as part of a required activity, the last group of face-to-face students was asked to provide written feedback on classroom discussions and activities they valued most, content they recommended be retained for the blended course, and new ideas that could be piloted in the new version. This feedback was considered as the new, blended version was developed.

Internal technical and programming resources were utilized throughout the development of the online materials. Programming support was made available through support from the training grant, allowing for a 50% position for a programmer with experience and knowledge in the creation of online courses. The programmer sought to: (1) design and develop the online courses based on the professional modular framework and object oriented programming technology so that new courses and learning materials can be easily integrated in the online system, (2) integrate multi-media and interactive e-learning materials that enhance learning, support thinking and problem solving, and (3) collect and represent data in many ways to give educators more opportunities for feedback, suggestion, and adjustment, including those where educators evaluate the teaching quality of courses; have opportunities to trace and review students efforts on each section/chapter to help educators thinking differently about learners and learning, adding/reducing the barriers between students and teachers. Additional technical support was made available through the Academic Computing and Communications Center (ACCC). ACCC provides a variety of computing, networking and telecommunication services. The multiple programming and telecommunications resources facilitated the initial development and offering of the grief course as well as its continuing availability.

Conclusion

Developing online courses on sensitive topics such as dying loss and grief are challenging. We demonstrated that by using an experiential approach and with well established strategies for successful online learning, we were able to develop and teach a blended course on dying, loss and grief that was extremely well received by the learners. We encourage other educators to consider this approach for teaching sensitive content in other areas.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The development of the course described in this manuscript was supported by the Advanced Practice Palliative Care Training Grant; US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 1 DO9HPO2996. Manuscript preparation was supported by the Center for End-of-Life Transition Research, Grant # P30 NR010680, National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health.

We are grateful to David Shuey, Dr. Shiping Zong, and Mark Mershon who worked with us to develop the online components of the course and to the students who completed NUSC 520 and gave us such valuable feedback to convert the traditional face-to-face approach to a blended course.

References

- 1.SUPPORT Investigators. A Controlled Trial to Improve Care for Seriously Ill Hospitalized Patients. JAMA. 1995;274(20):1591–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkie DJ, Brown MA, Corless I, Farber S, Judge K, Shannon S, Wells M. Toolkit for Nursing Excellence at End-of-Life Transition, Nurse Educators’ (TNEEL-NE) CD ROM (Version 1) 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrell BR, Virani R, Malloy P. Evaluation of the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Project in the USA. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2006;12(6):269–276. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.6.21452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel LL, von Gunten CF, Ferris FD. The Education for Physicians on End-of-life Care (EPEC) Curriculum. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan AM, Lakoma MD, Billings JA, Peters A, Block SD. Teaching and Learning End-of-Life Care: Evaluation of a Faculty Development Program in Palliative Care. Academic Medicine. 2005;80(7):657–668. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garrison DR, Kanuka H. Blended Learning: Uncovering Its Transformative Potential in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education. 2004;7(2):95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolb DA, Boyatzis RE, Mainemelis C. Experiential Learning Theory: Previous Research and New Directions. In: Zhang RJSLF, editor. Perspectives on Cognitive, Learning, and Thinking Styles. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claxton CS, Murrell PH. Learning Styles: Implications for Improving Educational Practices. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education at the George Washington University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones A. The Lead Lecture as an Adjunct to Experiential Learning (An Appropriate Modality for the Introduction of Issues Related to Death, Loss and Change. European Journal of Cancer Care. 1997;6:32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1997.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfund R. Using computer-assisted learning to gain knowledge about child death and bereavement. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2005;11(11):591–597. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.11.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbaum ME, Lobas J, Ferguson K. Using Reflection Activities to Enhance Teaching about End-of-Life Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8(6):1186–1195. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ali NS, Hodson-Carlton K, Ryan M. Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning. Nurse Educator. 2004;29(3):111–115. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeBourgh GA. Predictors of Student Satisfaction in Distance-Delivered Graduate Nursing Courses: What Matters Most? Journal of Professional Nursing. 2003;19(3):149–163. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(03)00072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chickering AW, Ehrmann SC. Implementing the Seven Principles: Technology as Lever. AAHE Bulletin. 1996:3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huckstadt A, Hayes K. Evaluation of Interactive Online Courses for Advanced Practice Nurses. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2005;17(3):85–89. doi: 10.111/j.1041-2972.2005.0015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]