Abstract

Processing of lexical verbs involves automatic access to argument structure entries entailed within the verb's representation. Recent neuroimaging studies with young normal listeners suggest that this involves bilateral posterior perisylvian tissue, with graded activation in these regions based on argument structure complexity. The aim of the present study was to examine the neural mechanisms of verb processing using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in older normal volunteers and patients with stroke-induced agrammatic aphasia, a syndrome in which verb, as compared to noun, production often is selectively impaired, but verb comprehension in both on-line and off-line tasks is spared. Fourteen healthy listeners and five age-matched aphasic patients performed a lexical decision task, which examined verb processing by argument structure complexity, i.e., one-argument (i.e., intransitive (v1)); two-argument (i.e., transitive (v2)), and three-argument (v3) verbs. Results for the age-matched listeners largely replicated those for younger participants studied by Thompson et al. (2007): v3-v1 comparisons showed activation of the angular gyrus in both hemispheres and this same heteromodal region was activated in the left hemisphere in the (v2+v3)-v1 contrast. Similar results were derived for the agrammatic aphasic patients, however, activation was unilateral (in the right hemisphere for 3 participants) rather than bilateral likely because these patients' lesions extended to the left temporoparietal region. All performed the task with high accuracy and, despite differences in lesion site and extent, they recruited spared tissue in the same regions as healthy normals. Consistent with psycholinguistic models of sentence processing, these findings indicate that the posterior language network is engaged for processing verb argument structure and is crucial for semantic integration of argument structure information.

Keywords: verb argument structure processing, verb subcategorization, agrammatic aphasia, argument structure processing in normal ageing, fMRI investigations of verb processing, phrase structure building operations

Introduction

The processing mechanisms involved in mapping linguistic form onto meaning (or vice versa) during sentence comprehension (or production) are tied to verbs and the linguistic information that they encode. Syntactically, verbs subcategorize for a particular grammatical environment in which they must occur and they encode argument structure and thematic roles. That is, they designate participant roles, for example, the doer (agent) or the recipient (patient or theme) of actions (Carnie, 2002; Grimshaw, 1990; Levin & Rappaport Hovav, 1995). In this sense, verbs are relational in that they refer to the relation between entities specified in events. To illustrate, consider the verb cherish.

subcategorization: cherish V [NP]

argument structure: cherish <agent, theme>

The phrase structure rules of the English language obligate that in addition to a subject, the verb cherish requires an object NP. A cherishing event also involves two entities: an agent, someone or something doing the cherishing, and a theme, something being cherished.

Psycholinguistic and neurolinguistic studies examining argument structure processing show that verbs are highly tied to their arguments. For example, priming studies show that verbs prime for their arguments (Ferretti, McRae, & Hatherell, 2001). Verbs also appear to automatically activate their argument structure when encountered during sentence processing (Boland, Tannenhaus, & Garnsey, 1990; MacDonald, Pearlmutter, & Seidenberg, 1994; Shapiro, Brookins, Gordon, & Nagel, 1991; Shapiro, Zurif, & Grimshaw, 1989; Trueswell & Kim, 1998; Trueswell, Tanenhaus, & Kello, 1993). Shapiro and colleagues showed, for example, using a cross-modal lexical decision paradigm that lexical decision times to a visually presented target are longer for verbs like send as compared to verbs like fix when encountered in sentences. Send is a three-argument verb, which entails three participant roles (agent, theme, goal); whereas fix is a two-argument, obligatory transitive verb, which involves only two participants, agent and theme. The argument structure of send is, therefore, more dense than that of fix in that it encodes a greater number of arguments. In addition, the goal argument in send is optional in that it does not need to be overtly realized in sentences (e.g., The Red Cross AGENT sent supplies THEME cf. The Red Cross AGENT sent supplies THEME to the hurricane victims GOAL)1. These characteristics render the verb send more complex than the verb fix. Gorrell (1989) reported similar findings for obligatory transitive verbs (e.g., permit) as compared to intransitive verbs (e.g., remain).

Several studies have examined the neural correlates of verb processing. Most have compared general word classes to one another, for example, verbs to nouns. Such studies using event-related potentials show that verbs elicit left frontal anterior positivity and/or stronger desynchronization, not observed for nouns (Federmeier, Segal, Lambroza, & Kutas, 2000; Khader & Rosler, 2004; Schlesewsky & Bornkessel, 2004; and others). Results of PET and fMRI studies, however, are less clear-cut. Some find that verb (compared to noun) processing engages both left anterior and posterior tissue (Grossman et al., 2003; Herholz et al., 1996; Perani et al., 1999). For example, Perani et al. (1999) found verb, but not noun, activation in Broca's area and in the left middle temporal gyrus. Other studies have not found anterior activation; rather only posterior regions show verb-specific activation (Davis, Meunier, & Marslen-Wilson, 2004; Yokoyama et al., 2006). Still other studies find no differential activation for verbs compared to nouns (Tyler, Russell, Fadili, & Moss, 2001). Using a semantic categorization task and PET, Tyler et al. reported no differences between nouns and verbs (also see Soros, Cornelissen, Laine, & Salmelin, 2003, for a study using magnetoencephalography (MEG)). The lack of consistent findings across neuroimaging studies may reflect a number of variables, including differences in the experimental tasks employed as well as the fact that verbs differ from nouns on a wide range of lexical, semantic, and usage dimensions, which are not always controlled. Further, as pointed out above, verbs vary crucially from one another based on their subcategorization and argument structure properties.

Recent neuroimaging studies, controlling verbs for their subcategorization and/or argument structure entries, serve to clarify these confounding results, at least in part. Thompson et al. (2007), in a study examining one-, two-, and three-argument verbs found graded argument structure effects in the angular gyrus for young unimpaired volunteers. Tissue in this region in the left hemisphere was active for processing two- versus one-argument verbs, and bilaterally for processing three- versus one-argument verbs. Importantly, verbs of each type were controlled for syntactic subcategorization; they differed only with regard to the arguments they encoded. Similar effects were reported by Ben-Shachar et al. (2003), Bornkessel et al. (2005), Shetreet, Palti, Friedmann and Hadar (2007) and Palti, Ben-Shachar, Hendler and Hadar (2007) who also found activation in the posterior perisylvian language network (PPN) relevant to argument structure processing. Namely, activation of the superior temporal gyrus and sulcus was reported for verbs with a more dense argument structure. These data indicate that the posterior perisylvian network is crucially engaged for processing information related to verb argument structure and is, thus, important for form-to-meaning processing during language comprehension.

One exception to these patterns was found by Shetreet et al. (2007). In addition, to PPN activation, they found additional left inferior frontal (BA 47) activation for verbs with more dense subcategorization frames. Rosler, Friederici, Putz and Hahne (1993) also observed subcategorization effects in the left frontal region in an event-related potential (ERP) study. Negativity in this region (i.e., in Broca's area and other frontal regions) associated with subcategorization violations was reported. These findings are in keeping with Humphries, Binder, Medler, and Liebenthal (2006) who suggested that frontal regions may be crucial for extracting syntactic structure independent of sentential meaning.

These findings are in line with neurolinguistic studies of patients with aphasia. Broca's aphasic patients with (primarily) left anterior brain damage show normal access to verb arguments during on-line sentence processing. That is, their reaction times (RTs) are longer for complex versus simple verbs, as they are in non-brain-damaged participants (Shapiro, Gordon, Hack, & Killackey, 1993; Shapiro & Levine, 1990). However, Wernicke's aphasic patients with primary damage to posterior, rather than anterior, language regions do not show differential RTs to verbs by type, indicating a lack of sensitivity to argument structure. This same Broca-Wernicke pattern shows up in grammaticality judgment studies: Broca's, but not Wernicke's, aphasic subjects show ability to detect anomalies in sentences with argument structure violations (McCann & Edwards, 2002; Kim & Thompson, 2000), suggesting that Wernicke's, but not Broca's aphasic patients, lack an ability to process verb arguments. Results derived from a recent study by Wu, Waller, and Chatterjee (2007) also support this pattern. They found deficits in thematic role (argument structure) knowledge in brain-damaged patients with lesions in the lateral temporal cortex.

Some patients with aphasia also have difficulty producing verbs, even when verb comprehension is relatively preserved (Miceli, Silveri, Villa, & Caramazza, 1984; Zingeser & Berndt, 1990). In particular, Broca's-type patients with agrammatism produce verbs with complex argument structure entries more poorly than simpler verbs with less dense argument structure. This pattern has been noted in English-speaking patients (Kegl 1995; Kemmerer & Tranel, 2000; Kim & Thompson, 2000, 2004; Thompson, Lange, Schneider, & Shapiro, 1997) as well as speakers of German (De Bleser & Kauschke, 2003), Dutch (Jonkers & Bastiaanse, 1996, 1998), Hungarian (Kiss 2000), Italian (Luzzatti et al., 2002), and Russian (Dragoy & Bastiaanse, 2009). These patients fail to produce complex verbs perhaps because anterior regions, which set up subcategorization frames, are damaged, precluding further argument structure analysis in posterior regions, However, because posterior language regions are spared, processing of verb arguments is possible as noted in on-line sentence processing and grammaticality judgment tasks.

This aim of the present study was to examine this latter postulate in patients with verb production difficulty, characterized by a profound verb argument structure hierarchy deficit, in the face of spared verb comprehension. Specifically, using a lexical decision task similar to that used by Perani et al. (1999), we queried whether or not these patients would show the same pattern as in on-line sentence processing and grammaticality judgment: that is, normal patterns of argument structure processing that engages the posterior language network (PPN). We hypothesized that, indeed, these patients, as well as age-matched healthy volunteers, would recruit spared tissue in the PPN region, bilaterally (where possible, depending on lesion site and extent), for verb argument structure processing, as do young non-brain-damaged volunteers (cf. Thompson et al's (2007) young normal participants).

It is now well known that neuronal loss in the language network, resulting from stroke, induces adaptive changes in the language network. There are two primary candidates for support of such adaptations: surviving tissue in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the lesion (usually the left hemisphere) may be recruited, and/or right hemisphere regions homologous to left brain language regions may become active (Cao, Vikingstad, Johnson & George, 1999; Samson et al., 1999; Thompson, 2000; Thulborn, Carpenter, & Just, 1999; and others). Completely novel pathways also may be recruited, however, this idea has received little support in the literature (see Zahn et al., 2004). Whether or not ipsilateral or contralateral recruitment, or both, result in the best recovery is a subject of ongoing debate (Belin et al., 1996; Crosson et al., 2007). Some suggest that the best recovery is associated with recruitment of left hemisphere, perilesional tissue (Belin et al. 1996; Martin et al., 2007; Naeser et al., 2004, 2005), whereas others suggest that recruitment of the right hemisphere is helpful, particularly for aspects of language that engage this region in healthy individuals (Breier et al., 2004).

As pointed out by Price & Crinion (2005), Thompson & Den Ouden (2008) and others, recruitment of right or left hemisphere networks to support recovery likely depends on several factors, including the anatomical location and extent of the lesion as well as the demands of the linguistic task performed. Crosson et al. (2007) suggested that small lesions generally lead to good recoveries supported by left-hemisphere mechanisms; whereas, right-hemisphere structures may provide a better substrate for recovery of language when much of the left-hemisphere language cortex is damaged (also see Graffman, 2000). The requirements of the linguistic task also may impact the extent to which right and/or left hemisphere tissue is engaged for processing. Calvert et al. (2000) for example, showed that their 28-year-old patient engaged the right hemisphere homologue of Broca's area for phonological, but not semantic processing.

An important issue in the analysis and interpretation of functional MRI data derived from aphasic individuals is the pathophysiological consequences of brain damage. For example, Bonakdarpour, Parrish and Thompson (2007) showed that in some patients with aphasia secondary to stroke, time-to-peak (TTP) of the hemodynamic response function (HRF) is delayed. This delay may result in underestimation or lack of detection of ongoing neural activity, particularly if a canonical HRF is used in analysis of functional MR data. Therefore, we included a separate long-trial event-related study in our experiment in order to estimate the HRFs of the aphasic study participants and used each patient's native HRF for data analysis.

Method

Participants

Aphasic Participants

Five right-handed, English-speaking individuals (four males), age 36-65 (M=53.6±11.6) years, with aphasia participated in the study. All presented with stroke-induced aphasia at least two years prior to the study and were diagnosed with agrammatic aphasia based on results of the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB, Kertesz, 1982) and other measures. WAB aphasia quotients (AQs) ranged from 64.1 to 82.4 (with the highest possible AQ being 100). Further, administration of the Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences (NAVS; Thompson, unpublished), a test which examines the ability to comprehend and name verbs controlled for argument structure, as well as to comprehend and produce both syntactically simple and complex sentences, showed that the patients' verb comprehension was relatively spared (M= 98.8%), however, verb production was impaired (M=67.2% correct) and all patients showed greater difficulty producing verbs with a greater number of verb arguments (i.e., three-argument verbs were more difficult than one- or two-argument verbs, and two-argument verbs were more difficult than one-argument verbs). In addition, sentence comprehension was superior to production (M=75.8% and 42.8%, respectively). In narrative discourse, sentences were short and ungrammatical; the patients produced more nouns than verbs; and deletion or substitution of grammatical morphemes was noted. Patient demographic information and language test scores are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data and Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) score for the aphasic participants.

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48 | 59 | 60 | 65 | 36 | 53.5 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Male | Male | |

| Handedness | Right | Right | Right | Right | Right | |

| Education | Masters Degree | Bachelors Degree | Some college | Masters Degree | Bachelors Degree | |

| Years Post Stroke | 3 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 5.6 |

| Language Test Data | ||||||

| Western Aphasia Battery | ||||||

| Information Content | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7.3 |

| Fluency | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4.2 |

| Comprehension | 9.4 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 8.6 | 8.7 |

| Repetition | 9.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 6.6 |

| Naming | 9.0 | 6.8 | 6.3 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 7.8 |

| Aphasia Quotient (AQ) | 86.4 | 64.1 | 64.2 | 77.8 | 74.4 | 73.4 |

| Northwestern Assessment of Verbs and Sentences Scores (% correct) | ||||||

| Verb Comprehension Test | 100 | 97 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 98.8 |

| Verb Naming Test | 77 | 53 | 57 | 72 | 77 | 67.2 |

| One-Argument Verbs | 92 | 74 | 70 | 88 | 88 | 82.4 |

| Two-Argument Verbs | 82 | 56 | 58 | 88 | 76 | 72.0 |

| Three-Argument Verbs | 58 | 30 | 44 | 50 | 66 | 49.6 |

| Sentence Production Priming Test | 64 | 02 | 54 | 57 | 37 | 42.8 |

| Sentence Comprehension Test | 97 | 51 | 77 | 71 | 89 | 75.8 |

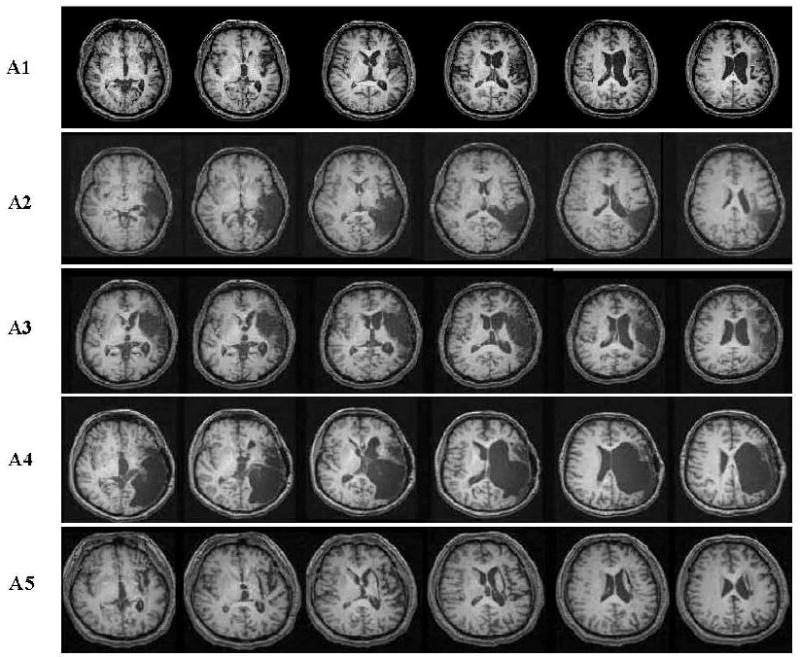

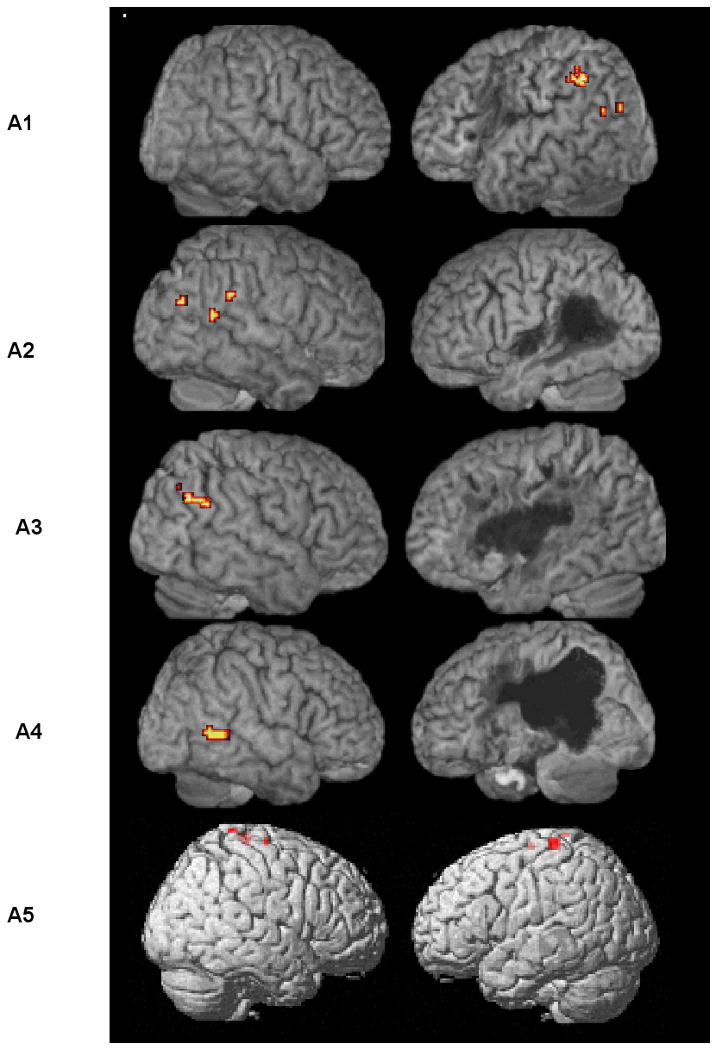

Structural MR scans showed differences in lesion size and localization in the left hemisphere across patients. Patients A1, A2, A3 and A4 presented with thromboembolic middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory infarctions, affecting cortical regions within its distribution. Whereas, Patient A5 suffered an intracranial hemorrhagic stroke, involving only subcortical tissue. Selected slices from each patient's T1 MR images are shown in Figure 1. The following provides a brief description of each patient's lesion:

Figure 1.

Axial anatomical T1 MRI scans from selected perisylvian slices in five aphasic participants. See text for details regarding lesion boundaries.

Patient A1. The posterior lateral aspect of the frontal lobe, including the lateral motor cortex and opercular part of Broca's area, was affected. Wernicke's area, the prefrontal cortex and most of the insula were undamaged and the lesion did not extend to the periventricular white matter.

Patient A2. Damage involved the superior and middle temporal gyri, and part of the inferior temporal gyrus, but spared the occipitotemporal junction. The lesion also extended medially to the posterior horn of left lateral ventricle.

Patient A3. Most of Broca's area, the middle frontal gyrus, part of the inferior parietal lobule and the superior temporal gyrus were involved. The lesion extended to the anterior horn of the left lateral ventricle and affected part of the anterior internal capsule.

Patient A4. Damaged regions included the posterolateral part of the frontal lobe, including the opercular part of Broca's area, and extended to the temporal lobe and inferior parietal lobule.

Patient A5. A subcortical lesion deep to the insula damaged the left basal ganglia and anterior and posterior limbs of the internal capsule.

Age-Matched Control Participants

Fourteen unimpaired participants (10 males) also were recruited for the study. These subjects were roughly age-matched to the aphasic participants, with ages ranging from 45-68 years (M=55.56±10.2). All were right-handed, monolingual English speakers with no history of neurological, psychiatric, speech, language or learning problems.

Stimuli

The stimuli were identical to those used in Thompson et al. (2007). To summarize, 250 lower case letter strings were used, which comprised 120 verbs, 80 nouns, and 50 pseudowords. The verbs included 40 one-argument, 40 two-argument, and 40 three-argument items (see examples 1 – 3, below).

Linger: one-argument verb as in: The actors AGENT lingered.

Consume: two-argument verb as in: The hikers AGENT consumed the chocolate THEME

-

Donate: three-argument verb as in: The winners AGENT donated the equipment THEME to the school GOAL

All verbs required agentive subjects; that is, no unaccusatives verbs such as fall or psych verbs such as amuse, which entail themes in the subject position, were included. In addition, complement verbs, such as believe or know, which select for a finite sentential complement, and verbs that select for infinitive clauses, such as want, were excluded. In general, noun/verb homographs were avoided (e.g., hammer), but when used, selected verbs had a noun usage less than 25% of their total frequency and selected nouns had a verb usage of less than 25% of their total frequency. (See Thompson et al. (2007) for a complete list of stimuli, verb/noun usage frequencies, and other details.) Nouns included 40 animals and 40 tools.

Within the categories of two- and three-argument verbs, verbs with both obligatory and optional arguments were included. For example, the verbs spend and eat are both two-argument verbs, but spend entails obligatory arguments and eat entails optional arguments; similarly, the three-argument verbs put and send, entail obligatory and optional arguments, respectively (see examples 4 – 7 below).

-

Spend: obligatory two-argument verb.

Argument structure: <Agent, Theme>

Context: The priest AGENT spent the funds THEME

-

Eat: Optional two-argument verb

Argument structure: <agent>; <agent,theme>

Contexts: The children AGENT ate; The children AGENT ate the cereal THEME

-

Put: Obligatory three-argument verb

Argument structure: <agent, theme, goal>

Context: The consultant AGENT put the program THEME on the computer GOAL

-

Sent: Optional three-argument verb

Argument structure: <agent, theme>; <agent, theme, goal>; <agent, goal, theme>

Contexts: The lady AGENT sent the flowers THEME; The lady AGENT sent the flowers THEME to the sick children GOAL; The lady AGENT sent the sick children GOAL the flowers THEME

The noun and verb stimuli were matched for number of syllables (1-2) and frequency of occurrence (M verb frequency = 9.5; SD=16.0); M noun frequency = 9.2; SD=12.9), using the CELEX database (Baayen, Piepenbrock, & van Rijn, 1993). Imageability ratings also were obtained (M for verbs = 376 (SD=126); M for nouns = 613 (SD=44)). Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test indicated no significant differences between verb and noun stimuli with regard to frequency (T+ = 1111.0, p = .23); however, the noun stimuli were significantly more imageable than the verbs (t(59) = 19.8, p < .001), as expected.

Verbs were selected for their argument structure status using the Brandeis Verb Lexicon (Grimshaw & Jackendoff, 1981) as well as findings from our own database (Dickey & Thompson, in preparation). In addition, we developed explicit criteria for classifying verbs and eight neurolinguists independently ranked each verb by type, with only verbs agreed upon by 7 of the 8 judges included as stimuli.

Verbs of each type were matched for frequency (M frequency of one-argument verbs = 9.5; two-argument verbs = 9.3, and three-argument verbs = 9.7) and imageability (M imageability for one-argument verbs = 418.3±148.5); two-argument verbs = 354.4±137.9); three-argument verbs = 341±107). There were no significant differences between verbs by type with regard to frequency (Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA: χ2 (2, N = 120) = 3.9, p = .14) or imageability (one-way ANOVA: F(2, 83) = 2.8, p = .067).

Finally, verbs with one and two obligatory arguments were tested for reaction time using a lexical decision task with presentation by SuperLab (Cedrus Corp., version 2.0, Phoenix, AZ) to 10 young unimpaired participants (4 males, age 20-35). Participants showed faster reaction times for one-argument than for two-argument verbs (one-argument = 599.6 (SD = 60.7); 2-argument = 604.9 (SD=59.2)), although this difference was not statistically reliable (Wilcoxon signed rank test; T+ = 30, p = .070)

Design and Procedures

An event-related design was used with stimuli divided into two runs, each including 125 pseudorandomized items (sequences were generated using the OPTSEQ program (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/optseq)). Words and pseudowords were visually displayed for 1200ms followed by a 500ms blank screen (inter-stimulus interval). Null events, consisting only of a fixation cross and lasting either 1700ms or 3400ms each, constituted 40% of the total time of each run.

A long trial event-related (ER) design also was developed in order to estimate the HRF of the aphasic participants. Fifty-one letter strings were used, including 17 nouns, 17 verbs and 17 pseudowords. Each trial was 30s in duration, consisting of 1200ms for stimulus presentation, a 500ms blank screen, a 26s large fixation cross, and a 2300ms small cross that prepared participants for the next trial. (See Bonakdarpour et al. (2007) for additional details.) Stimulus runs were prepared and presented to the subjects using SuperLab on a Compaq Pentium 4 computer with visual stimuli projected by an ELP Link IV, Epson projector onto a custom-designed, non-magnetic rear projection screen.

All subjects participated in preparatory training sessions using a simulated scanner located in the Aphasia and Neurolinguistics Research Laboratory at Northwestern University. This served to familiarize subjects with the experimental task and to screen for claustrophobia. In addition, aphasic participants were required to show RTs within 2500ms of stimulus presentation and accuracy at 90% or higher, which required between two and four 30-minute practice sessions for each patient. Scripts similar, but not identical, to those used during scanning sessions were presented for lexical decision, as in the main experiment.

A 3T Trio Siemens scanner was used to obtain both anatomical (T1-weighted) and functional scans (T2*-weighted), obtained in transaxial planes parallel to the AC-PC line. T1 preceded T2*-weighted scans for all participants and, for the aphasic patients, the long-trials experiment preceded the main experimental trials. T1-weighted 3D volumes were acquired using an MP-RAGE sequence with a TR/TE of 2100 ms/2.4 ms, flip angle of 8°, TI of 1100ms, matrix size of 256 mm × 256 mm; FOV of 22 cm, and slice thickness of 1 mm. Functional scans were obtained in the same orientation as the anatomicals, with a TR of 2000ms used to acquire 32 slices 3mm in thickness. Participants' heads were immobilized using a vacuum pillow (Vac-Fix, Bionix, Toledo, OH) with restraint calipers built into the head coil. Participants were provided with a non-magnetic button press device, which enabled recording of responses. Participants were instructed to respond to visually presented letter strings by pressing one button for words and another for non-words. Response latencies and accuracy were recorded.

Data analysis

The FMRI data were analyzed using SPM2 (Welcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute for Neurology, University College London) running in a Matlab 6.5 environment (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA). Functional scans were corrected for slice-acquisition timing and realigned to a mean functional image. Next, the data were filtered for low frequency drifts with a high pass filter of 256s. The anatomical volume was co-registered to the mean image, and normalized to the MNI 152-subject template brain (ICBM, NIH P-20 project). The functional volumes were then normalized using the same transformation and were smoothed using a 10mm (FWHM) isotropic kernel.

For all participants, conditions were modeled separately for verbs and nouns and for verbs by type: one- (v1), two- (v2), and three-argument verbs (v3) using a general linear model (Friston et al., 1995). We also modeled verbs for transitivity, collapsing object-taking two- and three-argument verbs. For the age-matched healthy volunteers parametric, random effects, analyses then were undertaken to (a) evaluate the effects of the number of argument, and (2) the effects of transitivity. Follow-up pairwise whole brain analyses comprised second-level (random effects) analyses for each contrast of interest. All second-level statistics were thresholded voxel wise at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons per FDR (Genovese, Lazar, & Nichols, 2002; Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995), a correction ensuring that, on average, no more than 5% of activated voxels in each contrast were false positives. A three-voxel extent threshold was also used.

For the patients, parametric analyses were not undertaken due to heterogeneity of lesion site and extent and HRF differences across participants (see below). Second-level analyses also were not performed. Rather we analyzed the data individually for each patient. For each contrast, we examined significance at the voxel and cluster level (corrected for multiple comparisons per FDR). We also examined “set level” significance, which “… refers to the inference that the number of clusters comprising an observed activation profile is highly unlikely to have occurred by chance and is a statement about the activation profile, as characterized by its constituent regions” (p.5; Flandin & Friston, 2008).

The long trials data for the aphasic individuals were analyzed using Brain Voyager (QX 1.4, Maastricht, The Netherlands), running in a Windows XP environment. HRF latency maps were formed using linear correlation lag analysis of the stimulation onsets and the time series on a voxel by voxel basis. Six regions of interest (ROIs) in each hemisphere were chosen, based on results with normal individuals reported in Bonakdarpour et al. (2007), as the foci of the HRF estimation. These regions were the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG; BA 44 & 45), the superior temporal gyrus (STG; BA 22), the middle temporal gyrus (MTG; BA 21), the angular gyrus (AG; BA 39) and the supramargial gyrus SMG (BA 40). The map was then thresholded at r=0.11-0.20, depending on signal to noise. Within a suprathresholded region of interest, a stimulus-locked average formed the HRF curve for that particular cluster. The resulting HRF curve for each region was then transferred to SPM2 using a script written by Stephen Fix and general linear analysis with SPM2 was used to determine activity within each ROI.

Results

Age-Matched Participants

Behavioral Data

The mean response accuracy for the age-matched controls was 98% across all Verbs and Nouns. Reaction time (RT) for Verbs was 616.31±186.4 ms and that for Nouns was 625.46±206.83 ms. For one-, two-, and three-argument verbs, RTs were 609.3±193.6, 613.3±184 and 626.31±181.6 ms, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between RTs for Verbs and Nouns (Wilcoxon, p=0.68), nor were there significant differences between verbs by type (Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA, p=0.84). See Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

RT and accuracy data for verbs and nouns for aphasic participants and the age-matched controls.

| Nouns | Verbs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Accuracy (%) |

RT (ms) |

SD | Accuracy (%) |

RT (ms) |

SD |

| A1 | 88.8 | 870.24 | 219.24 | 90 | 739.28 | 193.84 |

| A2 | 94 | 891.9 | 292.46 | 89 | 949.41 | 327.70 |

| A3 | 94 | 675.67 | 168.83 | 88 | 847.19 | 199.67 |

| A4 | 87.5 | 933.71 | 329.7 | 81.6 | 749.78 | 344.63 |

| A5 | 95 | 764 | 194.8 | 94.2 | 969.58 | 271.43 |

| Aphasic Group means | 91.86 | 827.1 | 241.0 | 88.56 | 851.05 | 267.46 |

| Age-Matched Control Group means | 98 | 625.46 | 206.83 | 98 | 616.31 | 186.40 |

Table 3.

RT means and standard deviations (in ms.) for verbs by argument structure type for aphasic participants and age-matched controls.

| One-Argument | Two-Argument | Three-Argument | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| A1 | 724.73 | 243.96 | 736.25 | 166.37 | 756.87 | 171.19 |

| A2 | 936.18 | 313.59 | 950.78 | 329.06 | 961.28 | 340.47 |

| A3 | 843.23 | 194.78 | 848.89 | 197.54 | 849.45 | 206.70 |

| A4 | 729.90 | 349.35 | 727.05 | 309.78 | 792.40 | 374.77 |

| A5 | 906.75 | 193.54 | 1003.11 | 307.05 | 998.87 | 313.69 |

| Total Aphasic group | 828.16 | 259.04 | 853.17 | 261.96 | 871.77 | 281.36 |

| Total Age-matched group | 609.3 | 193.6 | 613.3 | 184 | 626.31 | 181.36 |

Activation Patterns

Main effects for verbs and nouns were obtained by comparing activation under both conditions to the low level, cross fixation baseline. Results showed significant bilateral activation in occipital regions (BA 18, 19), the angular gyrus (BA 39), the insula, and subcortical regions. Significant activations also were found in the left pre-central gyrus (BA 4) and superior and middle temporal gyri (BA 22, 21) and the right middle frontal gyrus (BA 9). Contrasts for Nouns minus Verbs and Verbs minus Nouns yielded no significant activation after correction for multiple comparisons. However, significant activation for verbs, but not for nouns, was found in the left STG and MTG. See Table 4 for coordinate and cluster size data.

Table 4.

Main effects of all verbs (left columns) and all nouns (right columns) compared to cross fixation for age-matched controls. Coordinates in MNI-space; cluster sizes in voxels.

| Verb Activation | Noun Activation | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Area | BA | Side | x | y | Z | T | cl sz | Side | x | y | z | T | cl sz |

| Middle frontal gyrus | 9 | R | 36 | 30 | 33 | 3.81 | 42 | ||||||

| R | 39 | 36 | 27 | 3.66 | |||||||||

| Pre central gyrus | 4 | L | -54 | 3 | 9 | 3.36 | 29 | ||||||

| Angular gyrus | 39 | L | -27 | -57 | 51 | 9.61 | 1560 | L | -51 | -24 | 51 | 29 | |

| L | -27 | -48 | 48 | 8.34 | R | 48 | -21 | 51 | 10.68 | 4159 | |||

| R | 42 | -27 | 51 | 15.79 | 2582 | R | 45 | -27 | 63 | 10.12 | |||

| R | 42 | -30 | 63 | 14.65 | |||||||||

| R | 33 | -48 | 48 | 10.70 | |||||||||

| Superior temporal gyrus | 22 | L | -51 | 3 | -6 | 4.57 | 9 | ||||||

| Middle temporal gyrus | 21 | L | -60 | -33 | 3 | 4.21 | 9 | ||||||

| Insula | R | 33 | 18 | 6 | 5.62 | 93 | L | -30 | 21 | 3 | 4.41 | 77 | |

| R | 21 | 6 | 6 | 3.82 | L | -45 | 3 | 6 | 3.57 | ||||

| Lingual gyrus | 19 | R | 24 | -90 | -6 | 7.27 | 610 | ||||||

| R | 27 | -96 | 3 | 7.03 | |||||||||

| R | 42 | -75 | -18 | 5.91 | |||||||||

| Inferior occipital gyrus | 18 | R | 24 | -90 | -15 | 8.09 | 806 | ||||||

| R | 42 | -63 | -18 | 8.08 | |||||||||

| Middle occipital gyrus | 19 | L | -30 | -72 | 27 | 3.85 | 993 | L | -21 | -93 | -3 | 13.88 | 1120 |

| L | -24 | -93 | 0 | 9.40 | L | -42 | -60 | -21 | |||||

| L | -30 | -90 | 12 | 9.26 | L | -27 | -90 | 3 | |||||

| L | -42 | -60 | -18 | 8.14 | |||||||||

| Cuneus | 18 | L | -3 | -81 | 18 | 3.79 | 3 | ||||||

| Putamen | -- | L | -21 | 0 | 9 | 10.63 | 203 | L | -24 | -3 | 9 | 4.27 | 41 |

| L | -24 | 18 | 3 | L | -9 | 9 | 12 | 3.67 | |||||

| R | 27 | -9 | 6 | 3.03 | 4 | ||||||||

| Thalamus | -- | L | -12 | -18 | 0 | 4.85 | 39 | R | 15 | -15 | 0 | 3.68 | 14 |

| R | 15 | -12 | 3 | 3.80 | 50 | ||||||||

Note: BA=Brodmann's area; cl sz=cluster size.

Argument Structure Effects

Parametric, random effects, analysis examining the effects of argument structure with values of one-, two- and three-arguments revealed a significant 39-voxel cluster (p < .001 uncorrected) in the left angular gyrus (-57, -66, 18; BA 39). However, parametric analysis based on transitivity, comparing purely intransitive verbs with object-taking verbs, revealed no significant voxels or clusters of activation.

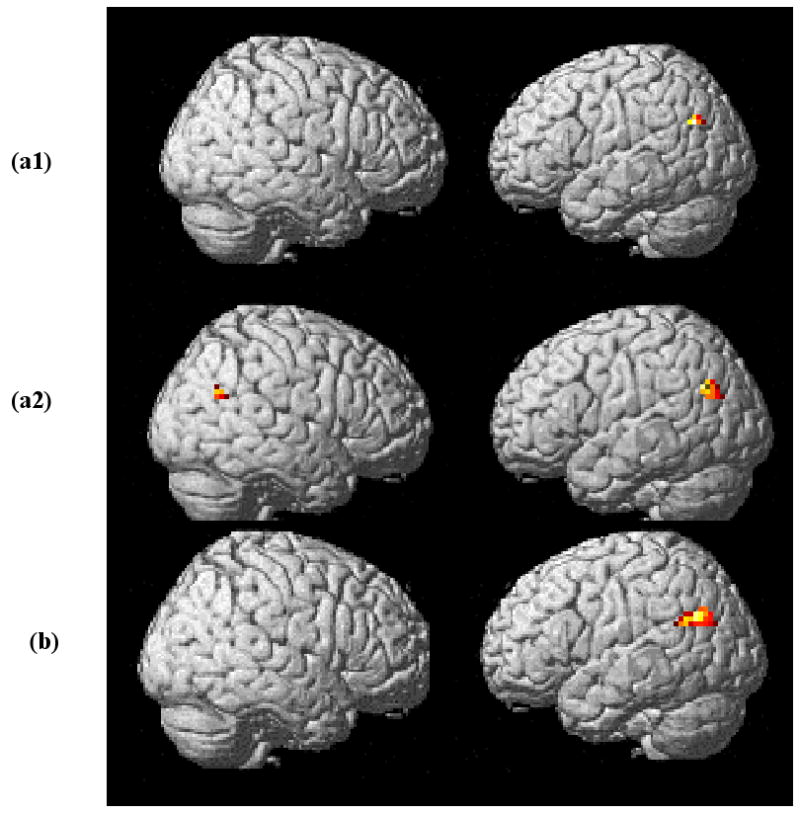

Follow-up pairwise whole brain analyses examining differential activation of verbs with fewer arguments minus those with a greater number of arguments yielded no significant results (v1-v2, v1-v3, and v2-v3). Comparisons of two- minus one-argument (v2-v1) and three- minus two-argument (v3-v2) also yielded no significant findings. However, when three-argument verbs were compared to one-argument verbs (v3-v1), a cluster of 52 voxels was active in the left angular gyrus (see Figure 2a1 and Table 5). This activation was significant at the cluster level (p=0.017) after correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 2.

(a) Activation for three-argument minus one-argument verbs (v3-v1) in age-matched control participants. (a1) Shows unilateral left angular gyrus activation after whole brain analysis (significant at cluster level (p=0.017) at k>30 after correction for multiple comparisons). (a2) ROI analysis (p=0.031, set level significance) shows activation of angular gyri in both the left and right hemispheres, with greater left hemisphere activation (cluster size left = 42; cluster size right = 15). (b) ROI analysis activation for two- and three-minus one-argument verbs (v2+v3)-v1. A significant 83-voxel cluster found in the left hemisphere (p=0.01, cluster level) is shown.

Table 5.

Activated regions and significance levels for three- minus one-argument verb (v3-v1) and three- plus two-argument minus one-argument verb (v3+v2)-v1 contrasts for healthy age-matched participants.

| Anatomical Area | x,y,z (mm) |

Cluster size (voxels) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

v3-v1 (whole brain analysis) at threshold>30 |

Left AG | -57 −66 18 | 52 | 0.017 (cluster level) |

|

v3-v1 ROI analysis for bilateral angular gyri |

Left AG | -48 −66 30 | 42 | 0.031 (set level) |

| Right AG | 48 −63 27 | 15 | ||

|

(v3+v2)-v1 ROI analysis for bilateral angular gyri |

Left AG | -45 −66 30 | 83 | 0.01 (cluster level) |

Note. AG=angular gyrus.

We also performed an ROI analysis in the angular and supramarginal gyri, bilaterally, selecting these site based on the activation patterns found in young normal participants reported in Thompson et al. (2007). For this the Wake Forest University (WFU) PickAtlas with normalized brains was used (Maldjian, Laurienti, Kraft, & Burdette, 2003). This analysis revealed significant neural activity in both hemispheres, however, activation in the left hemisphere dominated (cluster size left = 42 voxels, right = 15 voxels). The ROI analysis in both hemispheres was significant at p=0.031 (set level) (Figure 2a2; Table 5). Also using ROI analysis, comparison of two- and three-argument verbs with one-argument verbs [(v2+v3)-v1] showed a cluster of 83 voxels (p= 0.01, cluster level) in the left angular gyrus (Figure 2b; Table 5). No activation was detected when two- and three argument verb conditions were compared with one another (i.e., v2-v3 or v3-v2).

Aphasic Participants

Behavioral Data

For the aphasic participants, accuracy rate for all words was 90%: 89% for Verbs and 92% for Nouns. Reaction times (RTs) for Verbs (851.05±267 ms) were significantly longer than for Nouns (827.1±241 ms) (Wilcoxon, p=0.0004). For verbs by type, RTs were as follows: one-argument verbs: 828.16±259; two-argument verbs: 853.17±262; three-argument verbs: 871.77±281. Statistical analysis indicated no significant differences between RTs by verb type (Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA, p=0.86). See Tables 2 and 3.

Activation Patterns

Results of the long trial experiment showed that two of the aphasic participants (A2 and A5) showed HRF curves similar to those of normal participants (normal HRF=nHRF), with time-to-peak (TTP) in both anterior and posterior perisylvian regions, bilaterally, between 6 and 8 seconds (M=7.5s). A canonical HRF was, therefore, used to analyze activation patterns for these patients. The remaining three aphasic participants (A1, A3 and A4) showed abnormal HRFs (aHRF), with TTP ranging from 10-20 seconds in the left perisylvian region (M=16.35s) and from 10-16 seconds in the right (M=13.66s) (see Table 6). We, therefore, used individual participant's HRF for analysis of their fMRI data.

Table 6.

HRF time-to-peak across regions for aphasic participants.

| Region of Interest | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Inferior Frontal/Perilesional | 18 | 8 | 20 | 16 | 6 |

| Left Posterior Perisylvian/Perilesional | 10 | 8 | 18 | 16 | 8 |

| Right Inferior Frontal | 12 | 8 | 16 | 16 | 6 |

| Right Posterior Perisylvian | 10 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 8 |

Because of HRF differences as well as heterogeneity in lesion site and extent across participants as noted above, we present the fMRI data for the aphasic participants on a patient-by-patient basis. By doing so, we also avoid methodological problems encountered when averaging group effects in brain damaged patients. We also note that although the patients performed the lexical decision task with high accuracy (M=94% correct; range 92%-97%) we analyzed the data for correct trials only, which the event related design allowed.

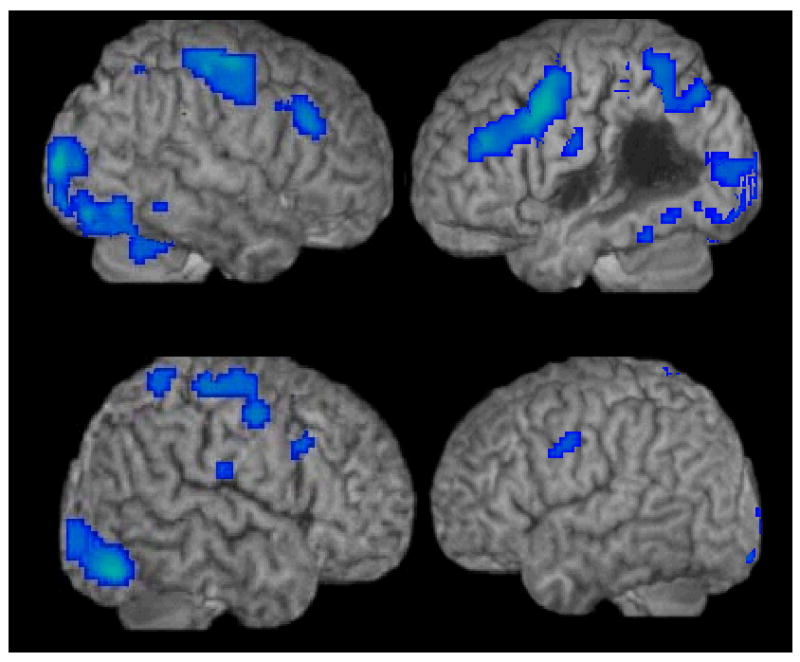

Patients A2 and A5. Main effect maps for Verbs and Nouns for the nHRF participants are shown in Figure 3. These maps were statistically significant at a p≤0.05 with False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons. Patient A2 (Figure 3a) showed activation comparable to the age-matched controls in both the left and right hemispheres (except for in left hemisphere lesioned tissue). Patient A5 (Figure 3b) showed lesser activation in the left hemisphere, however, in the right hemisphere activation was similar to the normal controls. The limited activation in the left hemisphere was likely due to the impact of this patient's subcortical lesion on both cortical and subcortical tissue.

Figure 3.

Main effects for all Words (Nouns and Verbs) for patient A2 (a) and patient A5 (b) who showed normal language area HRF curves (nHRF).

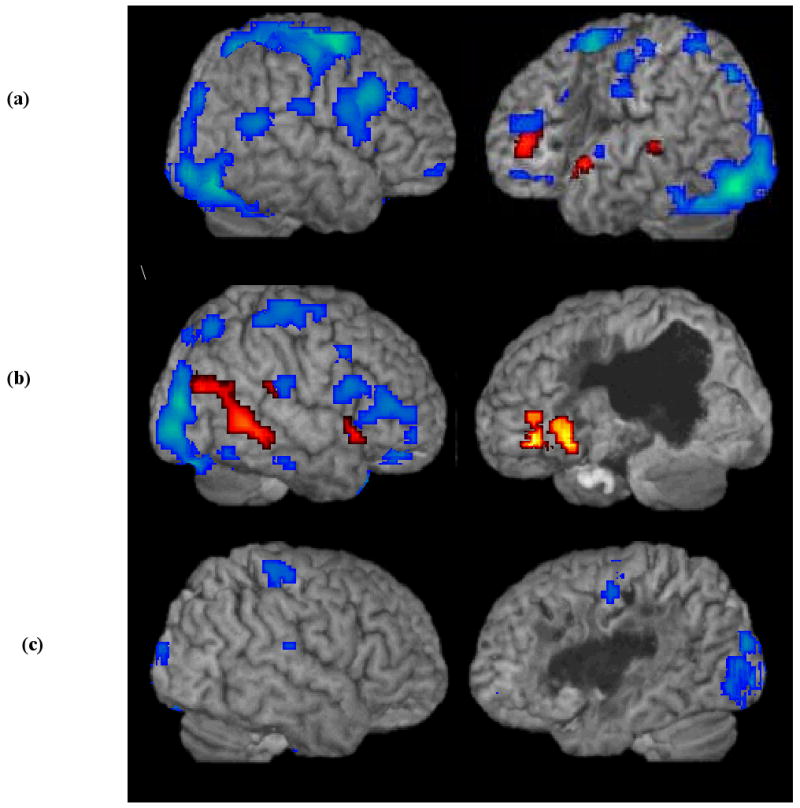

Patients A1, A3, and A4. Figure 4 shows the results of canonical HRF analyses (in blue) for Patients A1, A4, and A3. Subsequent ROI analyses in the IFG (BA 44 & 45), STG (posterior BA 22), MTG (posterior BA 21), AG (BA 39) and SG (BA 40), bilaterally, using each patient's native HRF revealed activations that were not present in the canonical analysis (shown in orange/yellow in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

FMRI activation maps for all Words (Nouns and Verbs) for three aphasic patients with abnormal language area HRF curves (aHRF): (a) patient A1, (b) patient A4, (c) patient A3. Canonical HRF analysis (blue); general linear model analysis using each patient's native HRF (orange/yellow). Note that patient 3 showed no significant activation in the ROI analyses using his native HRF.

For Patient A1 (Figure 4a), a significant 27-voxel cluster (p<0.0001) in the left STG and an 18-voxel cluster (p<0.006) in the left MTG were found for all Words in the RO1 analysis. A significant cluster of 13 voxels (p<.03) in the left IFG also was found. However, there was no significant activation in the right hemisphere in any of the ROIs. The ROI analysis for Patient A4 (Figure 4b), who presented with a large lesion extending to the left posterior language network, showed a significant 215-voxel cluster in the left IFG (p<0.001) that was not detected using a canonical HRF. In addition, in the right hemisphere activation in the STG, SMG and two maxima in the MTG were found (p<0.007). All activations were FDR corrected. Patient A3 showed no significant activation in any of the selected ROIs (see Figure 4c). (See Table 7 for activation coordinates for Patients A1 and A4.)

Table 7.

Significant activation derived from ROI analysis for Patients A1 and A4, using their native HRFs.

| Patient | ROI | Maximum coordinates x,y,z (mm) |

Cluster size (voxels) |

Z |

p value (FDR corrected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | |||||

| Left IFG | -21 24 -15 | 13 | 3.76 | 0.03 | |

| Left STG | -57 9 -3 | 27 | 5.44 | 0.0001 | |

| Left MTG | -69 -33 3 | 18 | 4.49 | 0.006 | |

| A4 | |||||

| Left IFG | -51 36 -15 | 215 | 4.98 | 0.001 | |

| -30 15 -12 | |||||

| -42 36 -9 | |||||

| Right MTG | 63 −48 −3 | 78 | 4.36 | 0.007 | |

| 45 −72 21 | 66 | 4.27 | 0.007 | ||

| Right SMG | 68 -31 22 | 10 | 4.17 | ||

| Right STG | 57 15 -6 | 18 | 4.03 | 0.007 | |

Note. IFG=inferior frontal gyrus, STG=superior temporal gyrus, MTG=middle temporal gyrus, SMG = supramarginal gyrus.

For the Nouns minus Verbs as well as the opposite contrast, Verbs minus Nouns, none of the aphasic participants showed significant activation. This lack of differential activation was noted under both canonical and corrected HRF analyses.

Argument Structure Effects

Because we analyzed individual activation maps for the aphasic participants we did not undertake parametric analysis of these data. Rather we used pairwise comparisons, examining for activation under each verb class condition as compared to all others. In keeping with findings derived from the age-matched control participants, none of the aphasic participants showed significant activation under contrasts of verbs with fewer arguments minus those with more arguments (i.e., v3-v2, v3-v1, v2-v1). However, four out of five aphasic participants (A1 – A4) showed activity in the posterior perisylvian network (PPN) for three- minus one-argument verb comparisons (v3-v1). (See Figure 5 and corresponding coordinate information presented in Table 8.) For Patient A1 significant activation was found in left hemisphere ROIs: the AG and pMTG (p=0.039; set level). Conversely, Patients A2, A3, and A4 showed significant activity only in right hemisphere regions. A2 showed three clusters of activation, one in the right AG and two in the pMTG (p=0.038; set level). Patient A3 activated a 15-voxel cluster in the right AG (p=.035; cluster level), and A4 activated a 51-voxel cluster in the right pMTG and pSTG (p=.043; cluster level). Activations were all significant after correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 5.

Aphasic participants' significant activation, corrected for multiple comparisons, for three- minus one-argument verbs (v3-v1) derived from ROI analysis in the Posterior Perisylvian Network (PPN). Patients A2, A3, and A4 showed significant activation in the right hemisphere PPN. For Patient A1, activation was in the left PPN (AG and pMTG). Patient A5 showed no significant perisylvian activity.

Table 8.

Activated regions and significance levels for three- minus one-argument verb (v3-v1) contrasts for the aphasic participants.

| Patient | Anatomical Area | x,y,z (mm) |

Cluster size (voxels) |

Significance level (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Left AG | -54 -51 45 | 19 | 0.039 (set level) |

| Left pMTG | -51 -66 24 | 4 | ||

| Left pMTG | -48 -78 24 | 4 | ||

| A2 | Right AG | 69 -39 33 | 6 | 0.038 (set level) |

| Right pMTG | 66 -51 18 | 3 | ||

| Right pMTG | 51 -72 27 | 3 | ||

| A3 | Right AG | 57 -63 9 | 15 | 0.035 (cluster level) |

| A4 | Right pMTG | 60 -54 3 | 51 | 0.043 (cluster level) |

| Right pSTG (Maximum) |

54 -42 3 | |||

| A5 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Note. AG=angular gyrus, pMTG=posterior middle temporal gyrus, pSTG=posterior superior temporal gyrus.

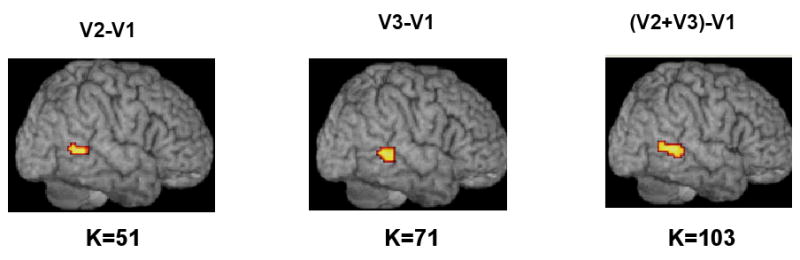

In addition, Patient A4 showed graded activation in the pMTG, with a 51-voxel cluster for the two-argument minus one-argument (v2-v1) contrast, a 71-voxel cluster for three-argument minus one-argument verbs (v3-v1), and a 103-voxel cluster for the two- plus three-argument minus one-argument contrast ((v2+v3)-v1). All were significant at p≤0.05 (FDR corrected) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Graded activation in the pMTG for three different verb contrasts for Patient A4. Two- minus one-argument (v2-v1) and three- minus one-argument (v3-v1) contrasts yielded clusters of 51 and 71 voxels, respectively, significant at p≤0.05 (FDR corrected). When two- and three-argument verbs where compared to one-argument verbs ((v2+v3)-v1) a larger cluster of activation (k=103) was found in the same area and at the same threshold.

Patient A5 showed no significant perisylvian activity in any of the ROIs for any of the argument structure contrasts. Even further ROI analyses in the superior parietal, temporal pole, and adjacent regions revealed no significant activation.

Discussion

Results of the present study showed that the network recruited for processing of nouns and verbs in the older volunteers was similar to that of younger normal participants reported by Thompson et al. (2007), with the exception of a few clusters of activation in Broca's area and the PPN, which were seen for young normals, but not for the older participants in this study. Age related reduction in signal peak detectability has been reported in other studies with older participants (Brodtmann et al., 2003; Buckner et al., 2000; D'Esposito, Zarahn, Aguirre, & Rypma, 1999; Huettel, Singerman, & McCarthy, 2001; Nielson et al., 2004). This is thought to result from decreases in signal to noise ratio due to greater noise level per voxel in elderly subjects (Heuttel et al., 2001; D'Esposito et al., 1999). Like the young normals, the age-matched group also showed no significant activations for Noun-Verb and Verb-Noun contrasts. This pattern supports that reported by Tyler et al. (2001) and Li et al. (2004), who found overlapping networks for nouns and verbs in English and Chinese speaking participants, respectively. However, when comparing the overlapping network, we found clusters of activation in the left pMTG, STS and temporal pole for verbs that were not seen for nouns. This finding is similar to that derived from Perani et al. (1999).

Activations derived during processing of all words for the aphasic participants differed somewhat across patients even though all patients performed the lexical decision task quite well, as did the age-matched healthy volunteers. High performance accuracy was expected because the task was selected explicitly to ensure this outcome. That is, we sought a simple task such that the aphasic participants could perform it well. Indeed, task difficulty can be a particular problem when studying language processing in brain-damaged patients with aphasia. If the patients cannot perform the task it is difficult to attribute derived activation patterns to the language process under study.

For Patients A2 and A5, who showed normal HRFs, main effects were similar to those found for the age-matched volunteers. The data derived from patients with altered HRF curves (Patients A1 and A4) supported the results of Bonakdarpour et al. (2007). When the HRF time-to-peak was delayed, analysis of fMRI activation using a canonical HRF (around 7 seconds post stimulus) resulted in a spurious lack of perisylvian activation, particularly in the lesioned hemisphere. When the native HRF was taken into account, missed activation was detected.

Argument Structure Effects

Parametric analysis of activation patterns of verbs by type showed that for the age-matched volunteers significant clusters of activation in the PPN (angular gyrus) were found, indicating that this region is engaged for argument structure processing. Interesting, when we parametrically analyzed the data for transitivity no significant activation was found. This finding indicates that the object-taking status of the verb, without regard to its ability to take multiple objects, did not appear to differentially impact its instantiation. Unlike the findings for the young normal listeners studied by Thompson et al. (2007), however, we did not find graded activation in the PPN associated with the number of arguments encoded by the verb. Comparison of two- and one- argument verbs showed no differential activation for the older healthy participants. A similar lack of two- minus one-argument verb activation was noted for four the five aphasic participants. Only P4 showed significant activation for this contrast; and for P4, activation was in the right PPN, whereas young normals activated the left hemisphere PPN. Less clear-cut activation was seen under the two- minus one-argument contrasts possibly due to a decrease in signal detection in older participants, as discussed above. However, this explanation is incomplete, considering that Patient A4 was the youngest of the aphasic patients (65 years).

More robust and consistent effects were found in the three-argument versus one-argument verb (v3-v1) comparison. The angular gyrus was activated in both hemispheres for the age-matched controls (as it was in the young normal participants studied by Thompson et al. (2007)). This finding supports those of other studies with young normal participants. Although the precise posterior regions recruited across studies vary somewhat, the results of all studies point to the inferior parietal, posterior middle and posterior superior temporal gyri complex (Ben-Shachar et al., 2003; Bornkessler et al., 2005; Hadar et al., 2002; Shetreet et al., 2007). These findings indicate that older normals utilize the same network as younger individuals when processing verb argument structure.

The aphasic participants showed a similar pattern, with the exception of Patient A5, who did not show significant PPN activation for verb argument structure processing. Instead, high parietal regions were active for verbs with more dense entries. PPN activation also was not found for this patient in the all Word, Noun and/or Verb conditions. Perhaps subthreshold activation and/or lack of adequate SNR precluded our detecting perisylvian activation for this subject. Robust activation in the PPN, however, was found for all of the other patients. Notably, however, activation was unilateral, rather than bilateral. Patient A1 showed the effect in the left; whereas, Patients A2, A3, and A4 recruited right hemisphere PPN tissue. Further the (v2+v3)-v1 contrast revealed significant activation only for Patient A4, again in the right hemisphere.

There are several variables to consider when examining neural activation in stroke patients, including lesion volume and location. Indeed, in spite of similar language deficit patterns consistent with agrammatic aphasia, our patients showed heterogeneous lesions: A1 and A3 presented with mid-size lesions, which occupied primarily left anterior language regions and spared all or most of the tempero-parietal region. A2s' lesion, also mid-sized, on the other hand, affected left posterior tissue, with a relative sparing of that in the anterior distribution of the left MCA. Patients A4 and A5 had the largest and most extensive lesions, which destroyed left frontal regions as well as portions of the left PPN. A4 presented with a large cortical lesion; whereas Patient A5's lesion was subcortical, but its widespread nature precluded blood flow to most of the left perisylvian language network.

On some accounts, lesion size and location is directly related to whether or not the right hemisphere is engaged for language processing following a left-hemisphere stroke. In general, bigger lesions are associated with greater right-hemisphere activation (Abo et al., 2004; Crosson et al., 2007; Graffman, 2000). Graffman (2000) attributes this hightened activation, at least in part, to transcollosal disinhibition. Following large left hemisphere infarctions, right hemisphere regions are no longer inhibited by the left hemisphere and are, therefore, free to function. As pointed out, however, the lesion volumes varied among our participants and none of them showed a complete loss of language tissue in the left hemisphere. Thus, lesion size and extent cannot completely account for the right hemisphere preference for argument structure processing found here.

It also has been suggested by Naeser and colleagues (Naeser et al., 2004; Naeser et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2007), Belin et al. (1996) and others that recruitment of right hemisphere tissue may result in less than optimal language performance. Again, our data do not provide strong support for this position. Indeed, response accuracy in the scanner was similar across participants and, as pointed out above, it was quite high. This high performance was seen in the face of no detectable left perilesional recruitment, with the exception of Patient A1 who activated this region, but did not show activation in the right hemisphere. These findings suggest that, even when available, left perilesional activation may not be required for task performance. It remains possible, and likely, however that for more difficult language processing tasks, recruitment of left perilesional tissue may be required, particularly if it turns out that perilesional tissue has latent language processing ability and/or because of a “redundant” capacity associated with its close approximation to premorbid language areas (see Zahn et al., 2002 for further discussion of “redundancy recovery”).

It is noteworthy that the right hemisphere regions activated for verb argument structure processing by the aphasic participants were the same as those recruited by both young and older normal participants for this purpose. This finding supports Breier et al.'s (2004) notion that when spared, tissue recruited by normals to support a particular language function remains viable for language processing following stroke. As pointed out by Zahn et al. (2004), engaging the right hemisphere as part of a completely novel pathway to support language will likely result in less than optimal language processing, however, this remains to be an open question.

In summary, verb argument structure processing in persons with agrammatic aphasia resulting from stroke is similar to that of their healthy age-matched peers. The aphasic participants were able to perform the task with high accuracy; in turn, they recruited a network similar to that of normal controls for argument structure processing. Despite differences noted in the site and extent of the patients' lesions, they recruited spared neural tissue in the same vicinity as healthy normals.

These findings indicate that the PPN is crucial for argument structure processing and offer a partial explanation for why Broca's, but not Wernicke's, aphasic patients do well at detecting argument structure violations, for example, when arguments are missing as in *John gives a car. or when they are present but violate the argument structure properties of the verb as in *John sleeps a bed. (Kim & Thompson, 2000; McCann & Edwards, 2000), and show normal patterns of accessing verb argument structure in on-line cross modal priming studies (Shapiro & Levine, 1990; Shapiro et al., 1993). Persons with Broca's aphasia often have lesions that spare the left posterior superior and middle temporal gyri and surrounding area, including the angular and supramarginal gyri. In fact, the patients studied by Shapiro and colleagues were selected explicitly for lesions of this nature. Notably, patients studied by Wu et al., (2007) who showed good ability to match sentences to pictures based on thematic role information also had spared cortical tissue in the middle and superior temporal gyri. Therefore, it appears likely that ability to perform such tasks was possible for the patients in these studies because critical PPN brain tissue was spared. However, as noted above, three of the patients in the present study had lesions that encroached on at least some left PPN tissue, forcing them to rely on the right hemisphere PPN to perform the task. Perhaps because we used a lexical decision task, a less resource-demanding task as compared to, for example, sentence processing, spared right hemisphere PPN tissue was adequate for task performance. This postulate leads to several testable hypotheses, including for example that our patients with left posterior PPN lesions would fail on more difficult argument structure processing tasks that putatively would require access to a bilateral PPN network. Whether or not argument structure processing can proceed normally with only right PPN tissue available or whether bilateral tissue is necessary for optimal performance is an open question.

Returning to our earlier discussion pertaining to the role that verbs play in the interface between form and meaning, the present research found activation in the PPN when verbs with greater argument structure density (i.e., v3 verbs) were contrasted with those of lesser density (i.e., v1 verbs), which supported the results of previous research as noted above. That is, as argument structure complexity increased activation of neural tissue in the PPN was seen, indicating that this region is crucial more so for processing and integrating the arguments selected by the verb, as opposed to generating and/or computing their syntactic form. It is possible to speculate then that syntactically relevant subcategorization frames, which trigger phrase structure building, do not crucially rely on posterior portions of the language network. Rather, argument structure processing requires the PPN, which triggers semantic integration processes. Indeed, Shetreet et al. (2007) found iFG (and PPN) activation when verbs were contrasted based on their subcategorization frames. We suggest that this iFG activation may have derived from phrase structure building operations, triggered by verb subcategorization frames. In turn, the PPN was required for integration of verb argument structure.

This is in line with models of language processing (Bock & Levelt, 1994; Hagoort, 2003; Levelt 1999; Roelofs, 1992, 1993): entries in the mental lexicon are associated with syntactic properties, that is, syntactically relevant subcategorization frames. In turn, these syntactic properties trigger phrase structure building operations, i.e., generation of a hierarchically organized constituent structure. We propose that anterior regions of the language network are crucial for generation of syntactic frames associated with incoming lexical material, but that posterior regions are engaged for subsequent semantic processes, i.e., integration of syntactic and semantic information. This is not to suggest that frontal regions are not also involved in processing motor aspects of verbs, in particular, action verbs. The dorsal aspect of Broca's area (BA 44), for example, is thought to be crucial for integrating internal motor representations of hand/arm and mouth actions with external information about biological motion (Molnar-Szakacs, Iacoboni, Koski, & Mazziotta, 2005). Recent work has even shown that this region is engaged during processing of action-related sentences, suggesting that it is involved in processing of higher-level conceptual aspects of action understanding (Baumgaertner et al., 2007; Buccino et al., 2005; Tettamanti et al., 2005). The present experiment, however, controlled verbs for their argument structure entries and included both action verbs such as erase and imitate as well as non-action verbs such as elect and entrust (see Thompson et al., 2007, for a complete listing of verb stimuli). We suggest that frontal regions are crucially involved in selecting a syntactic frame based on the subcategorization entries for verbs, regardless of their status as action versus non-action entries, which in turn trigger posterior regions for integration of lexical material that satisfies these argument structure requirements. When both subcategorization, that is, selection restrictions, and argument structure representation are simple and straight forward, as they are in intransitive one-argument verbs, which subcategorize for a V only and select no internal verb arguments, the posterior language network is not required, at least to the same extent that it is when both are more complex.

Although this proposal awaits empirical testing, support for it is garnered by the results of neurophysiological (ERP) studies. Whereas some studies have found that access to a word's stored memory representation occurs very early, around 120 to 180 ms after the word is encountered in sentences (Penolazzi, Hauk, & Pulvermuller, 2007), left anterior negativity (LAN) and early left anterior negativity (ELAN), occurring between 100-500 ms, are found by violations of word-category constraints. These latter effects have been interpreted as functionally related to generating a syntactic structure for incoming words (Friederici, 1995; Friederici, Hahne, & Mecklinger, 1996). In contrast, semantic violations trigger a negative wave, i.e., the N400, occurring 400ms following such violations, suggesting a later time window for semantic integration. Although ERP effects are not anatomically precise in that any language related effect is associated with generators in a number of brain areas, the N400 is often largest over posterior scalp sites (Hagoort, Brown, & Osterhout, 1999). These data are in line with the idea that generating phrase structure is accomplished by anterior brain regions and that integration of meaning engages posterior perisylvian areas. (See Grodzinsky & Friederici (2006) and Humphries et al. (2006) for similar proposals.) We point out, however, that recent work has shown that semantic integration of words into their sentence context may occur earlier (i.e., from 120 – 300 ms post stimulus) (Penolazzi et al., 2007), however, this effect appears to be modulated by orthographic and phonological information. In our experiment the orthographic/phonological form of verb arguments was not provided: only the base form of verbs were presented for lexical decision. Nevertheless, we found posterior activation for verbs with greater argument structure density. We suggest that this activation reflected semantic integration of argument structure information.

Conclusion

The findings from this study show that processing verb argument structure engages posterior brain regions for both unimpaired adult listeners and age-matched persons with agrammatic aphasia. We conclude that this region is involved in computing the arguments selected by the verb.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the NIH, NIDCD ROI-DCO1948-15.

Footnotes

Some three-argument verbs also are alternating, which means that the Theme and Goal can exchange places in the surface structure (The principal sent the formula THEME to the teachers GOAL cf. The principle sent the teachers GOAL the formula THEME.

References

- Abo M, Senoo A, Watanabe S, Miyano S, Doseki K, Sasaki N, Kobayashi K, Kikuchi Y, Yonemoto K. Language-related brain function during word repetition in post-stroke aphasics. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1891–1894. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200408260-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Piepenbrock R, van Rijn H. The CELEX lexical database (Release 1) [CD-ROM] Philadelphia, PA: Linguistic Data Consortium, University of Pennsylvania; 1993. Distributor. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgaertner A, Buccino G, Lange R, McNamara A, Binkofski F. Polymodal conceptual processing of human biological actions in the left inferior frontal lobe. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25:881–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin P, Van Eeckhout P, Zilbovicius M, Remy P, François C, Guillaume S, Chain F, Rancurel G, Samson Y. Recovery from nonfluent aphasia after melodic intonation therapy: a PET study. Neurology. 1996;47(6):1504–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shachar M, Hendler T, Kahn I, Ben-Bashat D, Grodzinsky Y. The neural reality of syntactic transformations: Evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychological Science. 2003;14:433–440. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock K, Levelt W. Language production Grammatical encoding. In: Gernsbacher MA, editor. Handbook of Psycholinguistics. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 945–984. [Google Scholar]

- Boland JE, Tanenhaus MK, Garnsey SM. Evidence for the immediate use of verb control information in sentence processing. Journal of Memory and Language. 1990;29:413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Bonakdarpour B, Parrish TB, Thompson CK. Hemodynamic response function in patients with stroke-induced aphasia: Implications for fMRI data analysis. NeuroImage. 2007;36(2):322–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornkessel I, Zysset S, Friederici AD, Cramon Y, Schlesewsky M. Who did what to whom? The neural basis of argument hierarchies during language comprehension. NeuroImage. 2005;26:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier JI, Castillo EM, Boake C, Billingsley R, Maher L, Francisco G, Papanicolaou A. Spatiotemporal patterns of language-specific brain activity in patients with chronic aphasia after stroke using magnetoencephalography. NeuroImage. 2004;23:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodtmann A, Puce A, Syngeniotis A, Darby D, Donnan G. The functional magnetic resonance imaging hemodynamic response to faces remains stable until the ninth decade. NeuroImage. 2003;20(1):520–528. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buccino G, Riggio L, Melli G, Binkofski F, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G. Listening to action-related sentences modulates the activity of the motor system: A combined TMS and behavioral study. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;24:355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Sanders AL, Raickle ME, Morris JC. Functional brain imaging of young, nondemented, and demented older adults. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2000;12(Suppl. 2):24–34. doi: 10.1162/089892900564046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert GA, Brammer MJ, Morris RG, Williams SC, King N, Matthews PM. Using fMRI to study recovery from acquired dysphasia. Brain and Language. 2000;71(3):391–399. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Vikingstad EM, George KP, Johnson AF, Welch KM. Cortical language activation in stoke patients recovering from aphasia with functional MRI. Stroke. 1999;30(11):2331–40. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.11.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnie A. Syntax: A Generative Introduction. 1st. Malden, Oxford: Blackwell Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Crosson B, McGregor K, Gopinath KS, Conway TW, Benjamin M, Chang YL, Bacon Moore A, Raymer AM, Briggs RW, Sherod MG, Wierenga CE, White KD. Functional MRI of language in aphasia: A review of the literature and the methodological challenges. Neuropsychology Review. 2007;17:157–177. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9024-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasio AR, Tranel D. Nouns and verbs are retrieved with differently distributed neural systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:4957–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH, Meunier F, Marslen-Wilson WD. Neural responses to morphological, syntactic, and semantic properties of single words: An fMRI study. Brain and Language. 2004;89:439–449. doi: 10.1016/S0093-934X(03)00471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bleser R, Kauschke C. Acquisition and loss of nouns and verbs: Parallel or divergent patterns? Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2003;16:213–229. [Google Scholar]

- D'Esposito M, Zarahn E, Aguirre GK, Rypma B. The effect of normal again on the coupling of neural activity to the bold hemodynamic response. NeuroImage. 1999;10(1):6–14. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoy O, Bastiaanse R. Verb production and word order in Russian agrammatic speakers. Aphasiology. 2009:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Federmeier K, Segal JB, Lambroza T, Kutas M. Brain responses to nouns, verbs, and class-ambiguous words in context. Brain. 2000;123:2552–2566. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.12.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez B, Cardebat D, Demonet JF, Joseph PA, Mazaux JM, Barat M, Allard M. Functional MRI follow-up study of language processes in healthy subjects and during recovery in a case of aphasia. Stroke. 2004;35:2171–2176. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000139323.76769.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti TR, McRae K, Hatherell A. Integrating verbs, situation schemas, and thematic role concepts. Journal of Memory and Language. 2001;44:516–547. [Google Scholar]

- Flandin G, Friston KJ. Statistical parametric mapping. Scholarpedia. 2008;3(4):6232. [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD. The time course of syntactic activation during language processing: A model based on neuropsychological and neurophysiological data. Brain and Language. 1995;50:259–281. doi: 10.1006/brln.1995.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederici AD, Hahne A, Mecklinger A. Temporal structure of syntactic parsing: Early and late event-related brain potential effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 1996;22(5):1219–1248. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.22.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Worsley KJ, Poline JB, Frith C, Frackowiak RSJ. A general linear approach. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;2:189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Lazar NA, Nichols T. Thresholding of statistical maps in functional neuroimaging using the false discovery rate. NeuroImage. 2002;15:870–878. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorrell P. Establishing the loci of serial and parallel effects in syntactic processing. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1989;18:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Graffman J. Conceptualizing functional neuroplasticity. Journal of Communication Disorders. 2000;33:345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(00)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J. Argument structure. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw J, Jackendoff R. Brandeis Verb Lexicon. 1981 Electronic database funded by National Science Foundation Grant NSF IST-81-20403 awarded to Brandeis University. [Google Scholar]

- Grodzinsky Y, Friederici AD. Neuroimaging of syntax and syntactic processing. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2006;16:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman M, Koenig P, DeVita C, Glosser G, Moore P, Gee J, Detre J, Alsop D. Neural basis for verb processing in Alzheimer's disease: an fMRI study. Neuropsychology. 2003;17:658–674. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadar U, Palti D, Hendler T. The cortical correlates of verb processing: Recent neuroimaging studies. Brain and Language. 2002;83:175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P. How the brain solves the binding problem for language: a neurocomputational model of syntactic processing. NeuroImage. 2003;20:S18–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagoort P, Brown C, Osterhout L. The Neurocognition of Language. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Herholz K, Thiel A, Wienhard K, Pietrzyk U, von Stockhausen H, Karbe H, et al. Individual functional anatomy of verb generation. NeuroImage. 1996;3:185–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettel SA, Singerman JD, McCarthy G. The effects of aging upon the hemodynamic response measured by functional MRI. NeuroImage. 2001;13:161–175. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries C, Binder J, Medler D, Liebenthal E. Syntactic and semantic modulation of neural activity during auditory sentence comprehension. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:665–679. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.4.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers R, Bastiaanse R. The influence of instrumentality and transitivity on action naming in Broca's and anomic aphasia. Brain and Language. 1996;55:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkers R, Bastiaanse R. How selective are selective word class deficits? Two case studies of action and object naming. Aphasiology. 1998;12:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kegl J. Levels of representation and units of access relevant to agrammatism. Brain and Language. 1995;50:151–200. doi: 10.1006/brln.1995.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemmerer D, Tranel D. Verb retrieval in brain-damaged subjects: Analysis of stimulus, lexical and conceptual factors. Brain and Language. 2000;73:347–392. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz A. Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) Psychological Corp.; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Khader P, Rosler F. EEG power and coherence analysis of visually presented nouns and verbs reveals left frontal processing differences. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;354:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Thompson CK. Patterns of comprehension and production of nouns and verbs in agrammatism: Implication for lexical organization. Brain and language. 2000;74(1):1–25. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Thompson CK. Verb deficits in Alzheimer disease and Agrammatism: Implications for lexical organization. Brain and language. 2004;88(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0093-934x(03)00147-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss K. Effects of verb complexity on agrammatic aphasic's sentence production. In: Bastiaanse R, Gordzinsky Y, editors. Grammatical disorders in afasie. London: Whurr Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levelt W. Models of word production. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3:223–232. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01319-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin B, Rappaport Hovav M. Unaccusativity: At the syntax–lexical semantics interface. Cambridge: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Jin Z, Tan LH. Neural representations of nouns and verbs in Chinese: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2004;21:1533–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzzatti C, Raggi R, Zonca G, Pistarini C, Contardi A, Pinna GD. Verb-noun double dissociation in aphasic lexical impairments: The role of word frequency and imageability. Brain and Language. 2002;81:432–444. doi: 10.1006/brln.2001.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MC, Pearlmutter NJ, Seidenberg MS. Lexical nature of syntactic ambiguity resolution. Psychological Review. 1994;101:676–703. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]