Abstract

This study examined outcomes associated with the Family Check-Up (FCU), an adaptive, tailored, family-centered intervention to enhance positive adjustment of middle school youth and prevent problem behavior. The FCU intervention model was delivered to families in 3 public middle schools. The study sample comprised 377 families, and participants were randomly assigned to receive either the intervention or school as usual. Participation in the intervention was relatively high, with 38% of the families receiving the FCU. Participation in the intervention improved youth self-regulation over the 3 years of the study. Self-regulation skills, defined as effortful control, predicted both decreased depression and increased school engagement in high school, with small to medium effect sizes. The results have implications for the delivery of mental health services in schools that specifically target family involvement and parenting skills.

Keywords: Prevention, Parent training, Family therapy, Behavior problems, School-based

Introduction

The percentage of the youth population who have mental health problems has been increasing during the past decade. Reports suggest that 1 in 5 children have a mental health problem or diagnosable mental health disorder, and only 20% of these children receive the services they need (Biglan et al. 2003; Greenberg et al. 2003; Katoaka et al. 2002). Mental health problems, such as ADHD, depression, and addiction, pose a significant barrier to learning for a large percentage of the U.S. school population. Students with mental health diagnoses do not automatically qualify for services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Most children with mental health problems are served by regular education programs in schools and by school personnel (counselors, behavioral specialists) who provide additional support when needed. Although there are many empirically based programs that treat mental health issues in the schools, when these programs are delivered outside a research setting, effect sizes tend to be small (Weisz et al. 1995). Many of the programs to reduce problem behavior in schools are ineffective if they are not delivered systematically and with a high level of fidelity, which is challenging given the staffing and resources available at most schools (Hallfors et al. 2006).

The typical trajectory of mental health problems begins in early childhood with problem behavior and parent–child interactions that are disruptive to development. Patterns of interaction learned in the context of parent–child exchanges are then generalized to school settings, leading to the development of later behavior problems, academic difficulties, and school dropout (Loeber and Dishion 1983; Loeber et al. 1993). Inadequate family management skills are one of the most robust predictors of a variety of behavior problems and mental health outcomes for youth that include antisocial behavior, depression, and substance use (Dishion and Loeber 1985; Hammen et al. 1999; Patterson and Dishion 1988; Peterson et al. 1994).

Considerable evidence supports a developmental model linking compromised key family management skills, such as low levels of parental monitoring, with childhood antisocial behavior, academic failure, peer rejection, and emotional distress (e.g., Patterson and Stouthamer-Loeber 1984; Pettit et al. 1993; Stormshak et al. 2000; Webster-Stratton 1993). As children develop into adolescents, lack of monitoring and limit setting exacerbates existing behavior problems and leads to further academic failure (Dishion and McMahon 1998). Parent-mediated interventions that target parenting skills have been shown across multiple intervention studies to be the most effective for reducing risk behavior and preventing the development of later problem behavior in adolescence (Brestan and Eyberg 1998; Connell et al. 2007; Reid and Webster-Stratton 2001).

As such, parents play a key role in promoting academic success through effective parenting skills at home and through parent–school involvement, such as monitoring the completion of homework (Greenwood and Hickman 1991; Hill et al. 2004; McMahon et al. 1996). Parent involvement that is supportive rather than critical or intrusive enhances the academic achievement of children with mental health problems (Pomerantz et al. 2005; Rogers et al. 2009). Similarly, family cohesion and parental monitoring of behavior predict school engagement for ethnically diverse youth (Annunziata et al. 2006). Poor academic achievement is a risk factor for youth of all ages and is associated with a variety of health risk behaviors in adolescence, including substance abuse, depression, and violence (Hawkins 1997; Larson and Ham 1993). Family management skills together with parent–school involvement are necessary to bolster school success, so interventions that target these two competencies will likely increase youths' school success and achievement.

Although very few school-based, family-centered interventions directly target both parenting skills and academic achievement, some have been implemented successfully and have been shown to reduce problem behavior. Parent skills training is typically conducted in groups, and outcomes include decreased growth of youth substance use and problem behavior over time (Dishion and Andrews 1995; Mason et al. 2003; Spoth et al. 2004). Programs that add a tutoring, skill training, or academic component have shown increases in student achievement and school bonding (Hawkins et al. 2001; Spoth et al. 2008; Tolan et al. 2004). Brief academic interventions that include parent participation, such as homework interventions for ADHD youth, can also increase student achievement (Raggi et al. 2009).

The Family Check-Up Intervention Model

The family-centered, school-based Family Check-Up (FCU) is a second-generation strategy for children and adolescents with behavior problems and can be described as parent training (e.g., Forehand et al. 1984; Patterson et al. 1982). Although empirically validated, parent training programs aimed at improving the public health of youth are challenging to implement on a large scale generally because of low enrollment and lack of individualized focus (Stormshak et al. 2002). Thus, we began a program of systematic research to design a family-centered intervention that could be implemented in settings that include a wide number of diverse youth and families, such as public schools (Dishion et al. 1988). Through a series of randomized trials, we delivered the FCU model as a brief strategy designed to engage and motivate parents to improve their parenting practices and use services that optimally address their needs. The FCU model was heavily influenced by Miller and Rollnick's (2002) motivation-based Drinker's Check-Up. The empirically validated FCU has been shown to effectively reduce the growth of problem behavior, enhance parenting skills, reduce family conflict, and reduce substance use in middle school youth (Dishion et al. 2002; Dishion and Stormshak 2007).

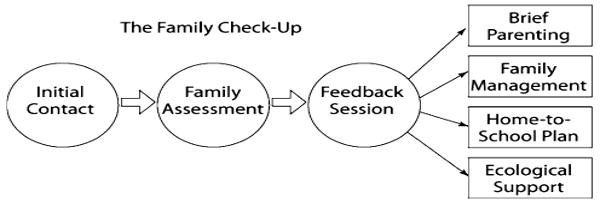

Briefly, the FCU involves three meetings with a youth's caregivers. The first meeting is an initial interview during which the practitioner facilitates a discussion with parents about goals and concerns and their personal motivation for change. This meeting establishes a collaborative tone for future meetings. The second session involves giving a packet of brief assessments to the parent, child, and teacher, and completing a videotaped family interaction assessment. The third meeting is a feedback session to discuss the results of the assessments in terms of (a) providing motivation to change and (b) identifying appropriate resources with respect to a menu of family-based intervention options. The feedback session is based on the work of Miller and Rollnick (2002) and uses motivational interviewing techniques.

The FCU can be used as a stand-alone, brief intervention or as a framework for building a relationship and continuing treatment with a family. Most families continue treatment, which is guided by the assessment conducted during the FCU. A wide range of school personnel can be trained to administer the model, including school counselors, behavioral support specialists, and assistant principals.

Self-Regulation and Academic Achievement

Self-regulation involves the ability to manage behavior and affect in settings with high distractibility. Youths who are better at regulating the allocation of attention to tasks at hand fare better in school than do students who are less well regulated (Boekaerts and Corno 2005). Students with higher levels of self-regulation are better able to engage in school assignments and tend to have higher GPAs (Boekaerts and Corno 2005; Gumora and Arsenio 2002). The degree of effortful control, described as the efficiency of executive attention (Rothbart and Bates 2006), offers insight into ways that youths regulate their experiences and exposure to negative thoughts or events. Youths higher in effortful control are better able to shift their attention from distressing thoughts and feelings to stimuli and activities that are more positive (Derryberry and Reed 2002; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Silk et al. 2003). Clearly, youths' self-regulation corresponds to a range of important outcomes, including peer competence, socioemotional functioning, and management of internalizing problems and externalizing problems (Davidov and Grusec 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2001, 2003, 2005; Oldehinkel et al. 2007).

This Study

We completed two longitudinal, randomized trials to test the efficacy of the FCU model delivered in schools during the adolescent years. The first study (Project Alliance 1, DA07031) is in the follow-up stages with youth who completed the intervention in middle school and who are now in their early twenties. We found that the FCU model delivered during the middle school years successfully reduced the growth of problem behavior, substance use, arrest rates, and depression (Connell et al. 2007; Connell and Dishion 2008; Dishion et al. 2002; Stormshak et al. 2009). These changes in problem behavior were mediated by family management skills, such as parental monitoring and positive support. We recently examined the effects of the FCU (Dishion and Stormshak 2007) on school achievement during the transition from middle school to high school. We found that contact with a parent consultant during the middle school years resulted in increased GPA and attendance for our intervention group compared with those of a matched control (Stormshak et al. 2009). These results are promising in that the FCU was designed to primarily target family management skills in the home, yet showed positive outcomes when it was delivered as a family-centered, school-based intervention.

The second study (Project Alliance 2; DA 018374) is in its fourth year, and participating youth are currently transitioning to high school. In this randomized trial, we focused our intervention specifically on home-to-school linkages and the family–school partnership. Family management skills, which remained central to the model, were promoted to families as critical to school success, and parents were engaged as active partners in their child's academic programming. By teaching skills such as home-to-school behavioral planning, we targeted youth behaviors that foster greater academic competence and school success. In this study, we were interested specifically in expanding on our previous research that examined the direct impact of our intervention on academic outcomes. Our goal was to test a meditational model of school engagement. We proposed that self-regulation—an individual-difference dimension that includes goals setting, task persistence, planning, and modulation of behavior and affect (Rothbart and Posner 2006)—is a mechanism by which negative youth outcomes are reduced and in turn, school engagement is enhanced. Self-regulation and effortful control are directly linked with better youth outcomes, including fewer conduct problems, less depressive symptoms, and better social adjustment (Eisenberg et al. 2001, 2005). In addition, self-regulation has been identified as a moderator of the link between peer deviance and later antisocial behavior in at-risk adolescents (Gardner et al. 2008). That said, it is critical to recognize the influence of the family context on children's self-regulation. Parent–child interaction plays an important role in the development of children's regulatory functioning (Denham 1998). Children whose parents interact positively with them develop more adaptive self-regulation strategies in the context of warm, positively engaged parents (Eisenberg et al. 2001, 2003, 2005) and greater parental monitoring and parental involvement (Purdie et al. 2004).

Because the FCU targets these parenting dimensions, we hypothesized that it would directly support the development of youths' self-regulation, which in turn would promote improved psychological functioning and school engagement. This was evaluated using an auto-regressive design over four waves of data to evaluate the effects of the FCU on youths' self-regulation, depressive symptoms, and school engagement from sixth to ninth grade. We used an intention-to-treat (ITT) design to capture the “net effect” of this intervention for the school as a whole, given that only a subset of students participated in the intervention. Finding ITT effects in this framework would suggest that the FCU intervention, although received by only a subset of students, has schoolwide effects. Thus, we tested whether there were intervention effects on youth self-regulation as a part of the mechanism promoting better psychological adjustment and school engagement. Accordingly, we predicted that self-regulation would be associated with decreased depressive symptoms and increased school engagement during the transition to high school.

Method

Participants

Participants were 377 adolescents and their families across three public middle schools in an urban area of the country. An unbalanced approach to randomization was used to enhance the power to detect intervention effects specifically for families electing to engage with the selected level of intervention. During the sixth grade year, 277 families (73%) were randomly assigned to the intervention condition, and 100 families (27%) were randomly assigned to the control condition, in which families experienced “school as usual” without access to any of the intervention services available to families in the intervention condition. Youth were followed through middle school into the first year of high school (4 years). Parents of all sixth grade students were invited to participate in the study, and 80% of all parents agreed to do so. Consent forms were mailed to families or sent home with youth. The sample comprised 51% male participants and 49% female participants. Student surveys were collected annually about all youth enrolled in the study. Approximately 80% of youth were retained across the 4 years of the study (grade 7, n = 329, 87% of sample; grade 8, n = 312, 83% of sample; grade 9, n = 289, 77% of sample). Families who moved were tracked and followed, via mailed surveys and phone interviews. The ethnicity of the sample was as follows: White (36%), Latino/Hispanic (18%), African American (16%), Asian (8%), American Indian (3%), and biracial/mixed ethnicity (19%). The average household income of families who participated in the study was between $30,000 and $40,000 per year, and the average education of parents was equivalent to a high school degree.

Intervention Protocol

The intervention model is a multilevel program that comprises three levels. The first level, the family resource center (FRC), is a universal intervention established in each of the middle schools. The FRC is staffed with a part-time parent consultant who provides services to families within the school context. The parent consultant attends behavioral support meetings, teacher meetings, and any other important school meetings related to child behavior. The parent consultant serves as a bridge between the school and the family and provides information to parents about their child's behavior, attendance, and homework completion. Brief consultations are also offered to parents, and they include topics such as homework completion and home-to-school planning. Furthermore, special seminars are provided about topics of interest to families in the school (e.g., supervising your teen during the summer).

The second level of intervention, the Family Check-Up (FCU), comprises three brief sessions that are grounded in motivational interviewing and are modeled after the Drinker's Check-Up (Miller and Rollnick 2002). The FCU was offered to all families who were randomly assigned to the intervention group. As previously described, it includes an initial home visit and interview; an ecological assessment, including parent report, child report, and a videotaped family interaction in the home; and a feedback session. In the feedback session, the parent consultant uses motivational interviewing strategies to summarize the results of the assessment. The primary goal of the feedback session is to explore potential intervention services that support family management practices and to motivate at-risk and high-risk parents to seek support for parenting and to make changes in family management. At this juncture, some families decline further services, whereas others move onto the third level, which is to receive consultation from the parent consultant and follow-up (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An overview of the Family Check-Up model

The parent consultants who delivered this service were full-time University of Oregon employees with intervention experience and expertise working with families. Their education level ranged from doctoral degree to bachelor's degree. For this project, parent consultant ethnicity was matched with family ethnicity whenever possible. Parent consultants reflected the primary ethnicities represented in this study and included one Latino consultant who speaks Spanish, one African American consultant, and two European American consultants. Consultants were trained through a series of workshops during the 3 years of the study, including 1-week-long initial training and several follow-up training workshops of equivalent length. Supervision was provided weekly by a doctoral-level practitioner and included feedback to consultants, planning for the FCUs, role plays, and support for using the family management curriculum.

The majority of the family management curriculum, which was used to create the brochures in the FRC, handouts for parents, and content of the follow-up intervention, was derived from the Adolescent Transitions Program curriculum, a well-developed and empirically validated parenting program (Dishion and Kavanagh 2003).

Of the 277 families in the intervention condition, 46% received consultation from a parent consultant and 38% received the full FCU intervention. Of the families receiving the FCU, 24% received additional follow-up work after the feedback, such as parent skills training or the development of a home-to-school plan. The median amount of time families who elected to participate in the FCU was 168 min. Of these families, 44% had daughters and 56% had sons. The majority of the contacts occurred with families when their child was between seventh and eighth grades (80%). A consideration basic to the intervention is the level of engagement by families of all demographics, such as gender and ethnic status. With respect to gender, 29.8% of families with a female target child elected to receive the FCU, and 34% of families with a male target child elected to receive the FCU. Ethnicity was not a significant predictor of engagement, with 49% of Latino families, 40.6% of European American families, 22.7% of African American families, and 21.3% of youth from other ethnic backgrounds participating in the FCU. No differences were found in the intervention group for those who elected to receive the FCU versus those who did not, in terms of self-regulation, t(275) = .237, ns; depression, t(276) = 1.023, ns; or school engagement, t(276) = .264, ns.

Assessment Procedures

In the spring term of each year, from sixth through eighth grade, students were surveyed with a questionnaire that measures a variety of problem behaviors. This questionnaire was derived from a survey used by the Oregon Research Institute (Metzler et al. 2001). Assessments were conducted primarily in the schools unless a student moved or was absent. In those cases, assessments were mailed to the home. Each youth who participated received $20 for each year he or she completed the assessment. The constructs for this study were correlated as expected (see Table 1), with adequate validity and reliability.

Table 1.

Correlations among the constructs

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FCU group | – | |||||||

| 2. Grade 6 self-regulation | −.01 | – | ||||||

| 3. Grade 6 depression | .03 | −.38** | – | |||||

| 4. Grade 6 school engagement | .03 | .39** | −.11* | – | ||||

| 5. Grade 7 self-regulation | .09 | .68** | −.25** | .28** | – | |||

| 6. Grade 8 self-regulation | .01 | .47** | −.23** | .23** | .60** | – | ||

| 7. Grade 8 depression | .03 | −.24** | .32** | −.06 | −.32** | −.39** | – | |

| 8. Grade 9 school engagement | .01 | .30** | −.09 | .34** | .31** | .41** | −.09 | – |

| M | .74 | 3.61 | 1.85 | 4.15 | 3.45 | 3.38 | 1.94 | 3.78 |

| SD | .44 | .58 | .79 | .77 | .57 | .53 | .85 | .90 |

Measures

Depression

Youth responded to a 14-item questionnaire relevant to depressive symptoms that was derived from items on the Child Depression Inventory (Kovacs 1992). Example item content included the following: depressed or sad, moody, sleep problems, cranky or grumpy, feeling worthless. Items content overlapped with diagnostic criteria for depression. Youth responded on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The scale was summed to create an overall score of depression. Cronbach's alpha for the scale = .953.

Self-Regulation

Effortful control was used as a measure of self-regulation. This scale included items such as “I have a hard time finishing tasks,” “It is easy for me to stop doing something when someone tells me to stop,” “It is easy for me to keep a secret,” “I stick with my plans and goals,” and “I pay close attention when someone tells me how to do something.” The scale was originally derived from the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (ATEMP; Ellis and Rothbart 2005). Cronbach's alpha for this scale = .79.

School Engagement

We measured school engagement with two items that reflect enjoyment of learning and effort to achieve (Wentzel 1989). The items included the following: “How often do you try to learn as much as you can about a new subject?” and “How often do you try to work hard to understand what you are studying?” The items were correlated as r = .686 and have been show to be associated with increased academic success and school engagement (Wentzel 1989).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the three outcome variables are shown in Table 1, as are bivariate correlations. A general pattern of moderate correlations was revealed between the variables both within time and across outcomes. However, the bivariate correlation between intervention group assignment and seventh grade self-regulation was not significant. The partial correlation controlling for sixth grade baseline variables (self-regulation, depression, and school engagement) indicated an association with increased self-regulation by seventh grade (r = .11, p < .05). Concurrent associations for sixth grade student functioning suggested that self-regulation was associated with lower levels of depression (r = −.38, p < .01) and higher levels of school engagement (r = .39, p < .01). Similarly, self-regulation in seventh grade was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms in eighth grade (r = −.24, p < .01) and higher levels of school engagement in ninth grade (r = .30, p < .01). These correlations provided initial support for the hypothesized model.

The FCU and School Engagement: Testing the Mediation Model

ITT analyses, in which intervention effects are evaluated by comparing the outcomes for all participants assigned to the intervention group with those of the control group, is an appropriate way to evaluate the effect of community-based interventions in real-world settings, as in this study. Significant improvement detected in the intervention group by way of ITT analyses would then suggest that implementation of the full prevention program yields significant effects in the targeted community. This approach is a conservative analysis for a program such as the FCU in which many families in the intervention condition receive no services at all.

Structural models were computed using Amos 16.0 (Arbuckle 2006). Model fit was assessed for each model tested, with preference given to models with nonsignificant χ2 values, comparative fit index (CFI) values of greater than .95, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) values of greater than .95, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) values of less than .06.

We used an ITT framework to evaluate generalized effects of the FCU in an autoregressive model. Thus, we tested the possibility that treatment group assignment was associated with increases in self-regulation in seventh grade, accounting for sixth grade self-regulation. In turn, we tested the extent to which seventh grade self-regulation predicted changes in depressive symptoms in eighth grade, accounting for sixth grade levels. Finally, we tested eighth grade self-regulation and depressive symptoms as predictors of youths' academic engagement in ninth grade, accounting for previous levels.

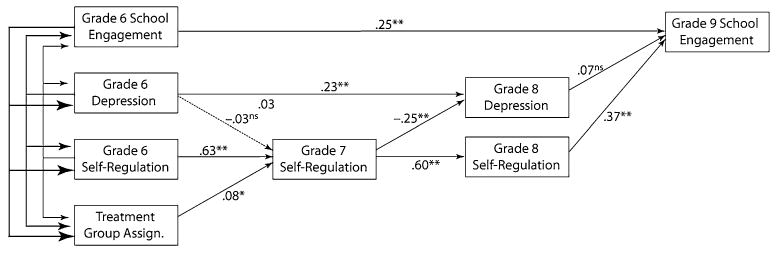

As shown in Fig. 2, this model yielded a good fit with the data, χ2(12) = 14.491, p = .27; CFI = .996; TLI = .987; RMSEA = .023 (90% CI .000–.060). Within the model, associations in constructs over time indicated stability, ranging from β = .23 to .63. Stability of youths' self-regulation was found from sixth to seventh grade (β = .63) and from seventh to eighth grade (β = .60). Depression also was stable from sixth to eighth grade (β = .23), and youths' school engagement was stable from sixth to ninth grade (β = .25). Further, this model accounted for 15% of the variance in youths' depressive symptoms in eighth grade and 21% of the variance in school engagement in ninth grade.

Fig. 2.

Intervention effects on self-regulation as a mediator of depression and school engagement. Note: χ2(12) = 14.491, p = .27; CFI = .996, TLI = .987; RMSEA = .023; residuals among W3 depression and W3 self-regulation were allowed to correlate to enable a test of unique variance explained by each variable. They were correlated r = −.25, p < .01, ns p > .05, * p < .05, ** p < .01

First, the effect of the intervention was tested on youth self-regulation and was significant. That is, participation in the FCU was associated with increases in self-regulation from sixth to seventh grade (β = .08). This finding is particularly meaningful because only 38.8% of those assigned to this condition completed the FCU. Although more than 60% of students in this condition received no family services, there was an overall group mean increase in self-regulation across the treatment group. In turn, seventh grade self-regulation was associated with decreases in youths' depressive symptoms from sixth to eighth grade (β = −.25), with a small to medium effect size. Interestingly, the reverse was not true: sixth grade levels of depression were not associated with changes in self-regulation by seventh grade. Finally, eighth grade self-regulation and depressive symptoms were each tested as predictors of ninth grade school engagement. Contrary to prediction, eighth grade depressive symptoms were not associated with youths' ninth grade school engagement. However, eighth grade self-regulation was associated with a medium effect size increase in school engagement by ninth grade (β = .37).

An invariance model was tested to evaluate whether the associations among the variables in the model were consistent for boys and for girls. To do this, we constrained the path coefficients and covariances to be equal for boys and for girls. Then, the model was recomputed and model fit was evaluated. This invariance model provided a good fit with the data, χ2(40) = 68.34, p < .01; CFI = .95; TLI = .91; RMSEA = .043 (90% CI .025–.061). This finding suggests that the pattern of relationships within the model did not significantly differ for boys and for girls, as a whole. Therefore, the overall model was retained for boys and girls together.

Discussion

This study focused on outcomes measured over 4 years after the implementation of the FCU intervention model in three middle schools and during the transition to high school. The 377 adolescent participants were randomly assigned to the FCU or to school as usual. The FCU intervention included diffusion of information in the schools about healthy parenting practices, a comprehensive family assessment and feedback, support for family management skills, and more intensive interventions designed to help parents reduce their youth's high-risk behavior at school and at home. Support for enhancing family–school relationship was also provided and was a key target of the intervention. We found that the relatively brief, family-centered, school-based approach to intervention had a positive effect on self-regulation, which in turn led to decreases in depressive symptoms for youth. Self-regulation was also directly related to higher levels of school engagement, whereas depression was not. These results emphasize the developmental importance of self-regulation for youth well-being and academic engagement. Drawing on this perspective, our findings suggest that the FCU intervention directly affected self-regulation and indirectly resulted in improvements in depression and school engagement during the transition to high school.

The results are promising in that they add complexity to a growing body of literature about family-centered, school-based prevention. There is substantial support for family-centered interventions that improve both parenting skills and child problem behavior over time (Connell et al. 2007; Spoth et al. 2002). However, studies of the links between family-centered interventions and academic process skills, such as school engagement, self-regulation, achievement, and attendance, have been limited (Stormshak et al. 2009). Moreover, very few studies have tested a meditational model and examined factors that relate specifically to changes in school-related outcomes. Our results suggest that indeed, direct effects of the family-centered intervention on self-regulation skills led to reductions in mental health problems, such as depression and school engagement, during the transition to high school.

The transition to high school is a critical area of study for a number of reasons. As youth start high school, parents often “disengage” from parenting and particularly from youth with problem behavior. We now understand that this process of “premature autonomy” is linked with the formation of deviant peer groups and the development of problem behavior (Dishion et al. 2000). Interventions that keep parents involved in their child's schooling and activities are essential to improve outcomes at this age and can prevent the development of subsequent negative behaviors. The transition to high school is also associated with increases in a variety of risk behaviors, including substance use and high-risk sexual behavior (Dishion et al. 1995). As youth begin to experiment with drugs and alcohol and become affiliated with deviant peers, their academic success begins to decline. This results in many high-risk youth leaving the public high school system to enter “alternative” programming or simply dropping out of high school altogether (Jimerson et al. 2000). That said, it is particularly notable that our study results show that family-centered, school-based interventions can help engage youth in school during this critical juncture and lead to academic success rather than school failure.

Dissemination and Real-World Implementation of the FCU

One limitation of our study is that the research was developed as an efficacy trial. Under the best conditions, we were able to affect outcomes for middle school youth. We hired our own parent consultants and paid families for their participation. The question remains, can schools administer this type of program without the support of research projects and federal grants? For example, Ennett et al. (2003) examined current practice in school substance abuse prevention programming across 1,795 middle schools in the United States. Results suggested that the majority of schools were implementing effective content, but very few used effective delivery strategies such as interactive delivery methods (17%). Similarly, Hallfors et al. (2006) randomly assigned youth across nine urban schools to receive an empirically based substance abuse prevention program that had been tested across multiple efficacy trials. When the program was administered as an effectiveness trial, the positive results from previous research were not replicated. The successful uptake of empirically based programs in schools involves both a commitment from the school to administer the program with fidelity and an assessment of outcomes that suggest positive results of the program.

A variety of contextual factors in schools are related to successful uptake of empirically based programs. These factors include administrative support for the program, teacher support for the program, financial resources to sustain the model, training and consultation in the model, and methods for managing staff turnover and other changes in the schools (Forman et al. 2009). When these factors are in place, prevention programs can be successfully integrated into school systems. For example, successful implementation of schoolwide positive behavior support programs in schools has resulted in significant reductions in office discipline referrals, improved school climate, and improved academic performance (Horner et al. 2004). To engage in positive behavior support, schools must be ready to implement the program, have appropriate staffing for a behavior support team, and administrative support for the model.

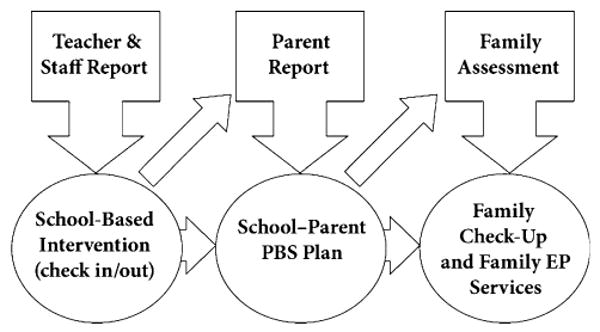

We have recently adapted the FCU model for dissemination in schools by reducing the amount of assessment involved in the intervention and streamlining the content for school personnel. The model will involve teacher and staff report of problem behavior that leads to a simple school-based intervention (check-in/out), parent assessment of problem behavior and home-to-school behavior planning with parents, and family assessments for those youth needing additional support using the FCU (see Fig. 3). The model will be simplified so that it can be administered by a variety of school personnel, including school counselors, behavior support specialists, and other support personnel employed by the school. The parenting content will be condensed into three main topic areas: positive behavior support at home, setting healthy limits, and family relationship building. Each of these areas will be an intervention focus for those families who receive the FCU. Administrative support staff who are willing to be trained in the model will be key stakeholders and will be active in shaping successful dissemination of this program.

Fig. 3.

Framework for integrating the Family Check-Up into the public school system

Limitations

Several study limitations should be acknowledged that are relevant to interpretation of findings. First, the primary outcome measures in this study were adolescent self-report. These assessments have a number of limitations, in that they may be biased and prone to social desirability. Some adolescents may feel uncomfortable reporting about their own behavior or may lose interest in the assessment and respond randomly. Our previous research suggests that self-report measures are related in the expected direction to a number of other measures from different raters, including teachers and peers (Dishion et al. 2008; Stormshak et al. 2005). A second study limitation is that we did not assess practical outcomes associated with the intervention, such as cost effectiveness or clinically significant changes in behavior. Future research that focuses on cost effectiveness would enhance our model for dissemination. Third, we did not compare students who received the FCU intervention with those in the intervention group who received no intervention services. Our prior research has revealed that families self-select into this intervention because they are at risk or experiencing problems with their adolescent (Connell et al. 2007). Future research should consider additional mediators that lead to changes in behavior, such as initial levels of risk and problem behavior. In previous research, we have specifically examined family engagement in the FCU intervention model as a mediator to changes in youth behavior (Stormshak et al. in press).

In summary, the FCU is a family-centered, school-based intervention designed to reduce problem behavior at school by targeting family management skills and parenting strategies at home. In Project Alliance 2, linkages between home and school performance were specifically targeted through a series of activities designed to enhance home-to-school behavioral planning, homework completion, and family–school involvement. The program resulted in increased school engagement, which was mediated by a direct association with self-regulation skills at school. In general, family-centered, school-based models of prevention are most successful when parents are engaged in the program and when schools are actively engaged in dissemination. Our next steps include dissemination of a model that can be simplified for uptake in an average, middle school setting.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA018374 to Elizabeth Stormshak and National Institutes of Health grant DA018760 to Thomas Dishion. We acknowledge the contribution of the Portland Public Schools, the Project Alliance staff, and participating youth and families.

References

- Annunziata D, Hogue A, Faw L, Liddle HA. Family functioning and school success in at-risk, inner-city adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(1):105–113. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos 7.0 user's guide. Chicago: SPSS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Biglan A, Mrazek P, Carnine DW, Flay BR. The integration of research and practice in the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist. 2003;58(6–7):433–440. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts M, Corno L. Self-regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2005;54(2):199–231. [Google Scholar]

- Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatment of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,275 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:180–189. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ. Reducing depression among at-risk early adolescents: Three-year effects of a family-centered intervention embedded within schools. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(4):574–585. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, Dishion TJ, Yasui M, Kavanagh K. An adaptive approach to family intervention: Linking engagement in family-centered intervention to reductions in adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:568–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Grusec JE. Multiple pathways to compliance: Mothers' willingness to cooperate and knowledge of their children's reactions to discipline. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(4):705–708. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Emotional development in young children. New York: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Reed MA. Anxiety-related attentional biases and their regulation by attentional control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):225–236. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.2.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW. Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: Immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:538–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, Kiesner J. Vicissitudes of parenting adolescents: Daily variations in parental monitoring and the early emergence of drug use. In: Kerr M, Stattin H, Engels RCME, editors. What can parents do? New insights into the role of parents in adolescent problem behavior. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2008. pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Capaldi D, Spracklen KM, Li F. Peer ecology of male adolescent drug use. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:803–824. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. Intervening with adolescent problem behavior: A family-centered approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K, Schneiger A, Nelson S, Kaufman N. Spoth RL, Kavanagh K, Dishion TJ, editors. Preventing early adolescent substance use: A family-centered strategy for public middle school. Universal family-centered prevention strategies: Current findings and critical issues for public health impact [Special Issue]. Prevention Science. 2002;3:191–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1019994500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Loeber R. Adolescent marijuana and alcohol use: The role of parents and peers revisited. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11:11–25. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Poulin F, Medici Skaggs N. The ecology of premature autonomy in adolescence: Biological and social influences. In: Kerns KA, Contreras J, Neal-Barrett AM, editors. Explaining associations between family and peer relationships. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2000. pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Reid JB, Patterson GR. Empirical guidelines for a family intervention for adolescent drug use. In: Coombs RE, editor. The family context of adolescent drug use. New York: Haworth; 1988. pp. 189–224. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in children's lives: An ecological, family-centered approach to mental health care. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Gershoff ET, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Cumberland AJ, Losoya SH, et al. Mother's emotional expressivity and children's behavior problems and social competence: Mediation through children's regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:475–490. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, et al. Longitudinal relations of children's effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Murphy BC, et al. The relations of parenting, effortful control, and ego control to children's emotional expressivity. Child Development. 2003;74:875–895. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Zhou Q, Spinrad TL, Valiente C, Fabes RA, Liew J. Relations among positive parenting, children's effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development. 2005;76:1055–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. Revision of the Early adolescent temperament questionnaire (EAT-Q) 2005. Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL, Thorne J, Rohrbach LA, Vincus A, Simons-Rudolph A, et al. A comparison of current practice in school-based substance use prevention programs with meta-analysis findings. Prevention Science. 2003;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1021777109369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Furey WM, McMahon RJ. The role of maternal distress in a parent training program to modify child noncompliance. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1984;12(2):93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Forman SG, Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Crowe M, Saka N. Evidence-based interventions in schools: Developers' views of implementation barriers and facilitators. School Mental Health. 2009;1:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TW, Dishion TJ, Connell AM. Adolescent self-regulation as resilience: Resistance to antisocial behavior in the deviant peer context. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:273–284. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9176-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O'Brien MU, Zins JE, Fredricks L, Resnik H, et al. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist. 2003;58:466–474. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GE, Hickman CW. Research and practice in parent involvement: Implications for teacher education. Elementary School Journal. 1991;91:279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Gumora G, Arsenio WF. Emotionality, emotion regulation, and school performance in middle school children. Journal of School Psychology. 2002;40(5):395–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Cho H, Sanchez V, Khatapoush S, Kim HM, Bauer D. Efficacy vs. effectiveness trial results of an indicated “model” substance abuse program: Implications for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(12):2254–2259. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Rudolph K, Weisz J, Rao U, Burge D. The context of depression in clinic-referred youth: Neglected areas in treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):64–71. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD. Academic performance and school success: Sources and consequences. In: Weissberg RP, Gullotta TP, Hampton RL, Ryan BA, Adams GR, editors. Healthy children 2010: Enhancing children's wellness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1997. pp. 278–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Guo J, Hill KG, Battin-Pearson S, Abbott RD. Long-term effects of the Seattle Social Development Intervention on school bonding trajectories. Applied Developmental Science. 2001;5(4):225–236. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0504_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Castellino DR, Lansford JE, Nowlin P, Dodge KA, Bates JE, et al. Parent academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variations across adolescence. Child Development. 2004;75(5):1491–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RH, Todd AW, Lewis-Palmer T, Irvin LK, Sugai G, Boland JB. The School-Wide Evaluation Tool (SET): A research instrument for assessing school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2004;6(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson SR, Egeland B, Sroufe LA, Carlson B. A prospective longitudinal study of high school dropouts: Examining multiple predictors across development. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38(6):525–549. [Google Scholar]

- Katoaka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Child Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Ham M. Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(1):130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Dishion TJ. Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;94:68–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Wung P, Keenan K, Giroux B, Stouthamer-Loeber M, van Kammen WB, et al. Developmental pathways in disruptive child behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mason WA, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Haggerty KP, Spoth RL. Reducing adolescents' growth in substance use and delinquency: Randomized trial effects of a parent-training prevention intervention. Prevention Science. 2003;4(3):203–212. doi: 10.1023/a:1024653923780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Slough N . Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Family-based intervention in the FAST Track program. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. pp. 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Metzler CW, Biglan A, Rusby JC, Sprague JR. Evaluation of a comprehensive behavior management program to improve school-wide positive behavior support. Education & Treatment of Children. 2001;24(4):448–479. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, Rerdinand RF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Effortful control as modifier of the association between negative emotionality and adolescents' mental health problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:532–539. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Chamberlain P, Reid JB. A comparative evaluation of parent training procedures. Behavior Therapy. 1982;13:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ. Multilevel family process models: Traits, interactions, and relationships. In: Hinde R, Stevenson-Hinde J, editors. Relationships and families: Mutual influences. Oxford, UK: Clarendon; 1988. pp. 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Stouthamer-Loeber M. The correlation of family management practices and delinquency. Child Development. 1984;55:1299–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Disentangling the effects of parental drinking, family management, and parent alcohol norms on current drinking by Black and White adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:203–277. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Family interaction patterns and children's conduct problems at home and school: A longitudinal perspective. School Psychology Review. 1993;22:403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Grolnick WS, Price CE. The role of parents in how children approach achievement: A dynamic process perspective. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, editors. Handbook of competence and motivation. New York: Guilford Publications; 2005. pp. 229–278. [Google Scholar]

- Purdie N, Carroll A, Roche L. Parenting and adolescent self-regulation. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggi VL, Chronis-Tuscano A, Fishbein H, Groomes A. Development of a brief, behavioral homework intervention for middle school students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. School Mental Health. 2009;1:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C. The Incredible Years parent, teacher, and child intervention: Targeting multiple areas of risk for a young child with pervasive conduct problems using a flexible, manualized treatment program. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2001;8(4):377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Wiener J, Marton I, Tannock R. Parental involvement in children's learning: Comparing parents of children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Journal of School Psychology. 2009;47(3):167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 99–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Posner MI. Temperament, attention, and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Vol 2. Developmental neuroscience. 2nd. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. pp. 465–501. [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, Morris AS. Adolescents' emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Kavanagh K, Dishion TJ. Family-centered preventive intervention science: Toward benefits to larger populations of children, youth, and families. Prevention Science. 2002;3:145–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1019924615322. Special Issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Randall GK, Shin C. Increasing school success through partnership-based family competency training: Experimental study of long-term outcomes. School Psychology Quarterly. 2008;23(1):70–89. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth RL, Redmond C, Shin C, Azevedo K. Brief family intervention effects on adolescent substance initiation: School-level growth curve analyses 6 years following baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):535–542. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Bierman KL, McMahon RJ, Lengua L Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Parenting practices and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:17–29. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp2901_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Connell AM, Dishion TJ. An adaptive approach to family-centered intervention in schools: Linking intervention engagement to academic outcomes in middle and high school. Prevention Science. 2009;10:221–235. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0131-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Dishion TJ, Light J, Yasui M. Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: Linking service delivery to change in problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:723–733. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Kaminski R, Goodman MR. Enhancing the parenting skills of Head Start families during the transition to kindergarten. Prevention Science. 2002;3:223–234. doi: 10.1023/a:1019998601210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB. Supporting families in a high-risk setting: Proximal effects of the SAFE children preventive intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(5):855–869. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. Strategies for helping early school-aged children with oppositional defiant and conduct disorders: The importance of home–school partnerships. School Psychology Review. 1993;22(3):437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Han SS, Granger DA, Morton T. Effects of psychotherapy with children and adolescents revisited: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome studies. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:450–468. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR. Adolescent classroom goals, standards for performance, and academic achievement: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1989;81(2):131–142. [Google Scholar]