Abstract

Objective

Absence of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) in mice reduces plasma triglycerides and provides protection from obesity and insulin resistance, which would be predicted to be associated with reduced susceptibility to atherosclerosis. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of SCD1 deficiency on atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results

Despite an antiatherogenic metabolic profile, SCD1 deficiency increases atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR)-deficient mice challenged with a western diet. Lesion area at the aortic root is significantly increased in males and females in two models of SCD1 deficiency. Inflammatory changes are evident in the skin of these mice, including increased intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and ulcerative dermatitis. Increases in ICAM-1 and interleukin-6 are also evident in plasma of SCD1-deficient mice. HDL particles demonstrate changes associated with inflammation, including, decreased plasma apoA-II and apoA-I and paraoxonase-1 and increased plasma serum amyloid A. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response and cholesterol efflux are not altered in SCD1-deficient macrophages. In addition, when SCD1 deficiency is limited to bone-marrow derived cells, lesion size is not altered in LDLR-deficient mice.

Conclusions

These studies reinforce the crucial role of chronic inflammation in promoting atherosclerosis, even in the presence of antiatherogenic biochemical and metabolic characteristics.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, inflammation, apolipoproteins, lipoproteins, hyperlipoproteinemia

Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) is the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids. It creates a cis-double bond in the Δ-9 position of palmitic (16:0) and stearic acid (18:0), thereby converting them to palmitoleic (16:1n7) and oleic acid (18:1n9) (1). Oleic acid is the major fatty acid found in triglycerides (TG) and cholesteryl esters (CE) (2), likely due to its status as the preferred fatty acid substrate of acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT) (3), and the close proximity of SCD to diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2 in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (4).

SCD1-deficient mice are protected from insulin resistance and diet-induced obesity (5) and have a markedly reduced rate of VLDL-TG production (6). We have recently shown (7) that SCD1 deficiency improves the metabolic phenotype of a hyperlipidemic LDLR-deficient mouse model of familial hypercholesterolemia (FH)(8). On a western diet, LDLR-deficient mice develop diet-induced diabetes and obesity and develop atherosclerosis over 2 to 3 months (8).

Absence of SCD1 reduces hepatic steatosis and plasma TG (by ~50%) and provides striking protection from diet-induced weight gain and insulin resistance in LDLR-deficient mice (7). A major unanswered question is whether the amelioration of these features in SCD1-deficient mice will lead to reduced susceptibility to atherosclerosis.

In this study, we show that despite these antiatherogenic metabolic characteristics, SCD1 deficiency surprisingly increases lesion size in hyperlipidemic LDLR-deficient mice and that this acceleration in atherosclerosis is likely to result from chronic inflammation primarily of the skin, which then leads to changes in markers of inflammation in plasma and proinflammatory changes in HDL.

Methods

An extended Methods section is available in the online supplemental materials (please see http://atvb.ahajournals.org). Mice carrying the Scd1ab-J (9) or Scd1ab-2J (10) null alleles were back-crossed to C57BL/6 for five generations to produce N5 incipient congenic mice and then crossed to the B6.129S7-Ldlrtm1Her mutant strain (11). The Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− control groups consisted of both littermates of Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice and additional age- and sex-matched Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice that were not littermates (~63% of all animals studied). Mice deficient in SCD1 with the Scd1ab-J allele were used in all experiments except those involving analysis of atherosclerotic lesions and (paraoxonase-1) PON1 activity, in which mice carrying a separately derived SCD1 deletion (the Scd1ab-2J allele) were also studied. Sections of the aortic root were stained as described in Singaraga et al (12).

Results

SCD1 deficiency increases atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice

Mice with a spontaneous deletion in Scd1 (B6.ABJ/Le-Scd1ab-J) were crossed with an existing dyslipidemic mouse model (B6.129S7-Ldlrtm1Her)(11) to generate mice with combined deficiencies of both LDLR (Ldlr−/−) and SCD1 (Scd1−/−). After 12 weeks of an atherogenic “western” diet (13), weights for male and female Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice were 44% and 54% higher than initial values, respectively, whereas neither male nor female Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice showed a significant increase in body weight, as described elsewhere (7). Total plasma TG was reduced by 44% and 51%, and non-HDL cholesterol was reduced by 8% and 27% in male and female Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice, respectively, relative to Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− controls. HDL cholesterol levels were unchanged by SCD1 deficiency. Absence of SCD1 also increased insulin sensitivity as measured by intraperitoneal glucose and insulin tolerance testing (7).

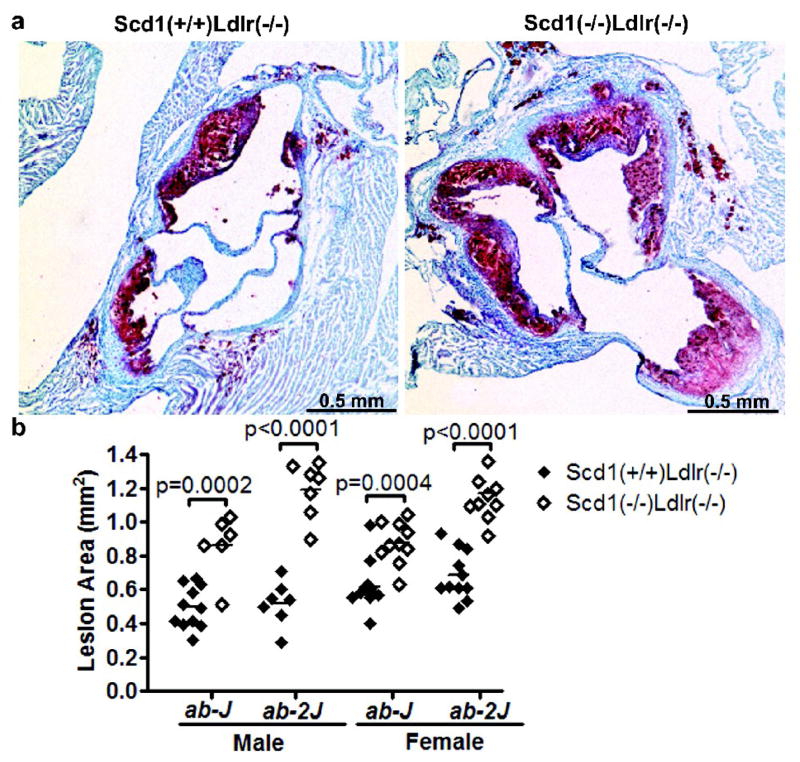

Atherosclerotic lesion size was evaluated in multiple sections of the aortic root in this same cohort of Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (males, n=6; females, n=10) and Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− control mice (males, n=11; females, n=11) (Fig 1a and b). Unexpectedly, both male and female SCD1-deficient mice have significantly increased lesion size relative to controls. Lesion area was increased by 74% in males (p = 0.0002) and by 41% in females (p = 0.0004).

Fig 1.

Lesion area in Ldlr−/− mice lacking SCD1. (a) Lesions in aortic roots of Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− (left) and Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− (right) mice carrying the Scd1ab-J allele were stained with oil red O to detect accumulation of lipids and photographed. (b) Quantitation of atherosclerotic lesion area in the aortic root. n = 6–11 mice per group.

In view of these observations in mice with the Scd1ab-J allele, we wished to examine whether these findings could be replicated in another cohort of mice carrying a different spontaneous null allele of Scd1 (B6.D1-Scd1ab-2J) (10). These mice were crossed with the same LDLR-deficient model and housed at a different specific pathogen-free barrier animal facility. Again, lesion area at the aortic root was increased in SCD1-deficient mice (129% increase in males; p < 0.0001; 70% increase in females; p < 0.0001; Fig 1b and Supplemental Fig I), thus supporting our initial findings. The effect remained significant when all mice that were not littermates were excluded from the analysis (data not shown).

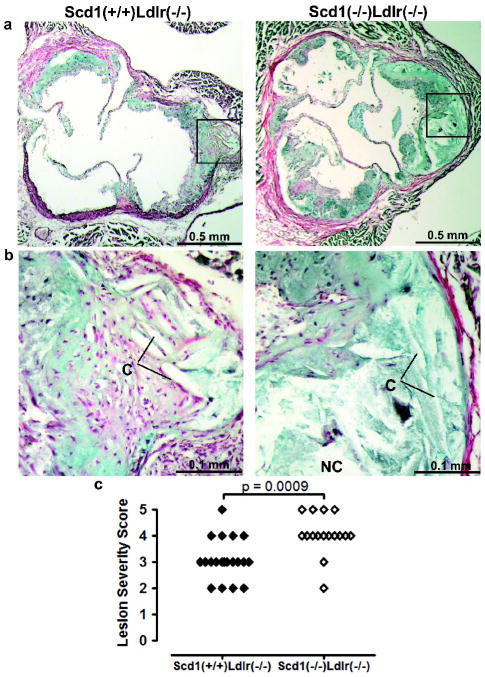

Aortic root sections from the first cohort of mice were stained with Movat’s pentachrome and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological examination. Extracellular matrix thickening and a cellular areas containing cholesterol crystals were apparent in the deeper portion of the lesions from Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice (Fig 2a,b and Supplemental Fig IIa). These findings were increased in the more advanced lesions of the Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice, with many extracellular cholesterol clefts in the large necrotic core underlying foam cell–rich regions. Staining for smooth muscle actin was evident in the media and fibrous caps of advanced lesions of both Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− and Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (Supplemental Fig IIb). The increased lesion size in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice fed the western diet for 12 weeks was characterized by greater absolute areas of macrophage infiltration in these animals versus Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− controls. This macrophage infiltration was evident in both the large complex atheromatous lesions in the left coronary sinuses, as well as the smaller lesions of the right coronary and noncoronary sinuses. The majority of cells in early plaques were positive for monocyte/macrophage staining in both Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− and Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (Supplemental Fig IIc).

Fig 2.

Lesion morphology Ldlr−/− mice lacking SCD1. (a,b) Necrotic cores (absence of purple/black nuclei, NC) and extracellular cholesterol clefts (needle-shaped lucencies; C) were observed with Movat pentachrome staining. The absence of yellow stain indicates the lack of significant collagen deposition. (c), Semi-quantitative assessment of lesion severity. n = 16–22 mice per group.

Semi-quantitative morphologic examination of sections stained with Movat’s pentachrome and H&E was used to assign lesion severity scores on a 0 to 5+ scale based on the following parameters: foam cell characteristics, cholesterol clefts, presence of necrotic core, degree and composition of fibrous cap, infiltration into the media, extracellular matrix deposition, calcification and plaque cellular characteristics. When examined in a blinded fashion, the aortic roots of Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice earned significantly higher lesion severity scores than Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− controls (p = 0.001; Fig 2c).

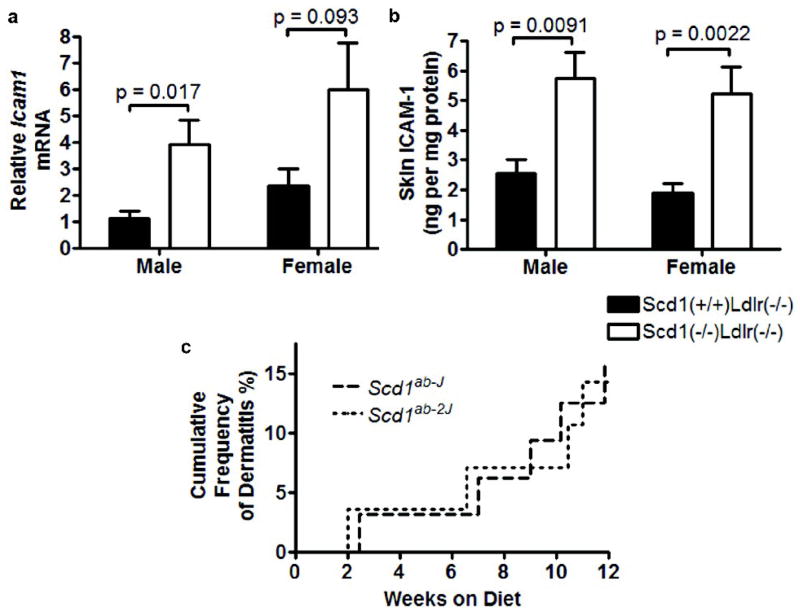

SCD1 deficiency promotes inflammation in Ldlr−/− mice

Prior dermatological and immunological studies have indicated that SCD1-deficient mice have skin that is rich in macrophages and mast cells (14, 15), indicative of chronic dermal inflammation. Icam1 mRNA was increased more than 2-fold in the skin of Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice relative to control Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice (males, p = 0.017; females, p = 0.093; Fig 3a) and skin ICAM-1 protein was increased more than 2-fold in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (males, p = 0.0091; females, p = 0.0022; Fig 3b).

Fig 3.

Skin of Ldlr−/− mice lacking SCD1. Levels of ICAM-1 mRNA (a) and protein (b). n = 5–6 mice per group. (c) Dermatitis in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice but not Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice (Scd1ab-J, p = 0.016; Scd1ab-2J, p = 0.023). n = 28–35 mice per group.

Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice have obvious skin abnormalities, including a hyperplastic epidermis and stratum corneum (Supplemental Fig IIIa). Severe spontaneous ulcerative dermatitis (Supplemental Fig IIIb,c) necessitated euthanasia of 14–16% of SCD1-deficient mice (Fig 3c). Diffuse inflammatory infiltration that included mast cells (Supplemental Fig IIIc), exudation of inflammatory cells and fibrin onto the surface of the skin, and proliferation of fibrous tissue and granulation in the dermis was evident (Supplemental Fig IIIb,c). We also observed mild to moderate lymphadenopathy, particularly protruding cervical and brachial lymph nodes, in mice with severe dermatitis. No Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice developed any skin lesions by the end of the study.

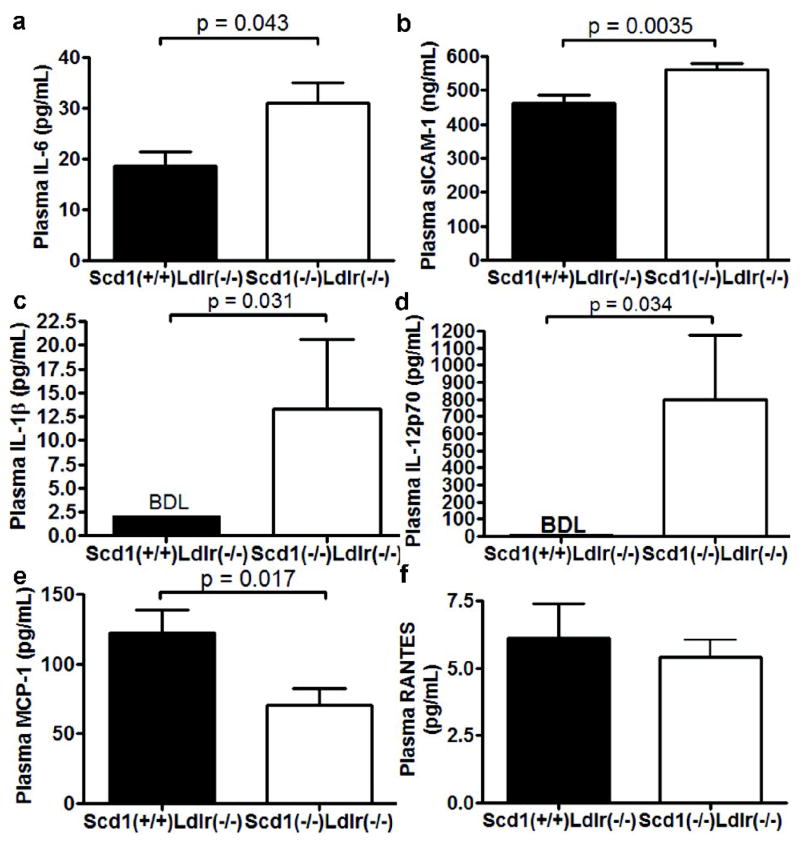

These findings prompted us to examine whether SCD1-deficient mice also have markers of systemic inflammation that may be contributing to atherosclerosis. Interleukin (IL)-6 is increased by 67% (p = 0.043; Fig 4a), and soluble ICAM-1, an adhesion molecule that is elevated in serum of patients with the inflammatory skin disorders psoriasis (16) and atopic eczema (17) was also increased in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (p = 0.0035; Fig 4b). Two additional pro-inflammatory cytokines known to be elevated in psoriatric skin lesions, IL-1β (18) and IL-12p70 (19), were detected in plasma from Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice but not Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− controls (Fig 4c,d).

Fig 4.

Inflammation in Ldlr−/− mice lacking SCD1. Plasma IL-6 (a), sICAM-1 (b), IL-1β (c), IL-12p70 (d), MCP-1 (e), and RANTES (f) levels were determined in mice fed a western diet. n = 8–12 mice per group.

Circulating levels of MCP-1 were decreased 2-fold in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (p = 0.017; Fig 4e). White adipose tissue is the major source of MCP-1 in obese mice (20), and the decreased levels of MCP-1 may be attributed to the significant decrease in white adipose tissue see in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice (7). The levels of RANTES (CCL5) were not significantly different (Fig 4f).

In the absence of a pro-inflammatory dietary stimulus, several inflammatory indicators in plasma were below the limit of detection in both Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− and Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− mice. Weak trends toward increased inflammatory indicators were seen in Scd1−/− Ldlr−/− mice relative to Scd1+/+Ldlr−/− controls, but these increases were not significant (Supplemental Fig IV).

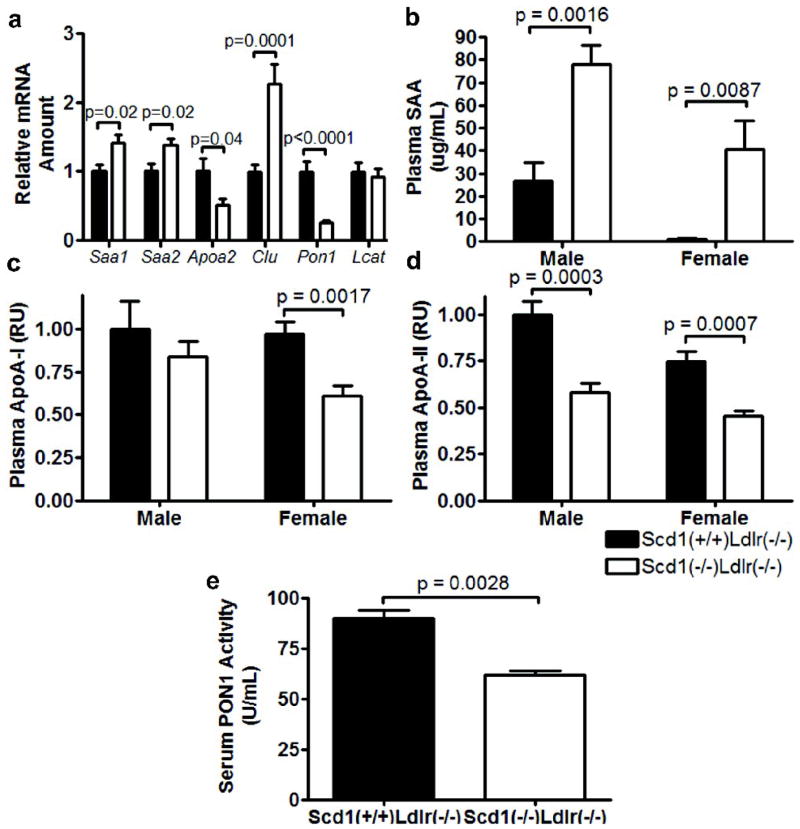

SCD1 deficiency alters HDL-associated proteins in Ldlr−/− mice

Inflammation has been shown to have a proatherogenic effect on the composition of HDL particles, such that they become depleted in specific proteins, such as apoA-I, apoA-II, and PON1, while enriched in serum amyloid A (SAA)(21). Indeed, in SCD1-deficient mice, plasma SAA is dramatically increased (females, 52-fold increase, p = 0.0087; males, 2.9-fold increase, p = 0.0043; Fig 5b), while plasma apoA-I (females, ~37% reduction, p = 0.0017; males, ~16% reduction, p = 0.44; Fig 5c) and apoA-II are decreased (~40% reduction; females, p = 0.0007; males, p = 0.0003; Fig 5d). The changes in plasma SAA and apoA-II were paralleled by significant changes in mRNA encoding these genes (Saa1, p = 0.017; Saa2, p = 0.017; Apoa2, p = 0.039 Fig 5a). Furthermore, hepatic mRNA levels of Pon1, the gene that encodes PON1, an enzyme that contributes to the antioxidant properties of HDL (22), are decreased by nearly 75% (p < 0.001; Fig 5a) while mRNA levels of Clu, the gene that encodes apoJ/clusterin, an acute phase HDL-associated protein (23), are increased by more than 2-fold (p = 0.0001; Fig 5a). No changes were observed in mRNA levels of Lcat (Fig 5a). SCD1-deficient mice also had a significantly lower serum PON1 activity (p = 0.0028; Fig 5e). These data indicate that SCD1 has a proatherogenic effect on HDL protein composition that may be attributed to chronic inflammation.

Fig 5.

HDL phenotype in Ldlr−/− mice lacking SCD1. (a) Relative amount of liver mRNAs. n = 12 mice per group. Plasma SAA (b), apoA-I (c), and apoA-II (d). Relative units (RU). n = 6–12 mice per group. (e) Serum PON1 activity. n = 3 mice per group.

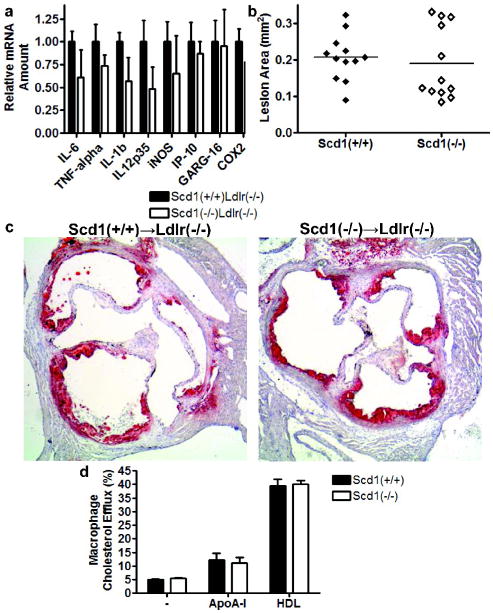

SCD1 deficiency does not alter macrophage function

The atherogenic effect of SCD1 deficiency could also result from a direct effect of SCD1 deficiency on macrophage function. If the increased macrophage infiltration is due to a direct effect of SCD1 deficiency in macrophages, we would expect an increased inflammatory response in SCD1-deficient macrophages.

We therefore evaluated the effect of SCD1 deficiency on the inflammatory response of thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal exudate cells (Fig 6a). Inflammatory gene expression was induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an agonist of toll-like receptor 4 signalling, and mRNA levels of several LPS-induced inflammatory proteins were assessed. No significant differences were observed in genes encoding IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-12p35, iNOS, IP-10, GARG-16 or COX2, suggesting that the increased atherosclerosis observed with SCD1 deficiency is not due to an altered macrophage inflammatory response.

Fig 6.

Macrophages from mice lacking SCD1. (a) LPS-induced mRNAs in thioglycollate-elicted peritoneal macrophages. Lesion area (b) and representative sections (c) of Ldlr−/− mice reconstituted with Scd1+/+ and Scd1−/ − bone marrow and fed a western diet for 6 weeks. n = 12 mice per group. (d) Cholesterol efflux assays from bone-marrow macrophages from Scd1+/+ and Scd1−/ − transplanted mice. n = 4 mice per group.

Macrophage SCD1 deficiency does not alter atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice

Another way to examine whether the atherogenic effect of SCD1 deficiency results from a direct effect on SCD1 deficiency in macrophages is to evaluate the effect of SCD1 deficiency in bone marrow-derived cells on atherosclerosis in vivo. Bone marrow from Scd1−/− and Scd1+/+ mice was transplanted into LDLR-deficient mice. At 6 weeks after bone marrow transplantation, the diet was switched from regular chow diet to western diet. After 6 weeks on the western diet, no skin lesions were observed in the transplanted mice, nor did SCD1 deficiency in bone marrow-derived cells have an effect on serum lipids (Supplemental Table I). Most importantly, no effect was observed between the two transplanted groups on atherosclerotic lesion size (0.207±0.018 mm2 in Scd1+/+→ Ldlr−/− mice versus 0.189±0.029 mm2 in Scd1−/−→ Ldlr−/− mice; Fig 6b,c), indicating that loss of macrophage SCD1 does not directly play a significant role in atherogenesis in these mice.

Overexpression of SCD1 has been reported to result in decreased cholesterol efflux in HEK293 and CHO cells (24). SCD1 deficiency had no effect on cholesterol efflux to apoA-I or HDL under our experimental conditions (Fig 6d), further supporting the fact that SCD1 deficiency is not associated with altered macrophage function.

Discussion

Despite an antiatherogenic lipid and metabolic profile, absence of SCD1 promotes inflammation and atherosclerosis in a mouse model of FH on a western diet. Absence of SCD1 also increases plasma IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12p70 and sICAM-1 levels and has a proinflammatory effect on the components of HDL particles, increasing SAA and apoJ/clusterin and reducing apoA-I, apoA-II, and PON1. Specific deficiency of SCD1 in bone-marrow derived cells does not influence atherosclerotic lesion size.

We have recently shown that SCD1-deficient mice have relatively reduced plasma triglycerides and are protected from obesity and insulin resistance (7), phenotypic components of the metabolic syndrome that have been linked to increased susceptibility to atherosclerosis (25, 26). These surprising data suggested that SCD1-deficient mice must have some proatherogenic stimulus that overcomes the antiatherogenic metabolic characteristics expected to reduce lipid accumulation in the aorta. Chronic inflammation has been reported in the skin of chow-fed SCD1-deficient mice, indicated by increased mRNA encoding ICAM-1 (15) and increased infiltration of macrophages and mast cells but only rare lymphocytes or neutrophils in the dermis (14). In addition, subcutanous cyclosporin A can inhibit ICAM-1 expression and reduce mast cell numbers in the skin, restoring the wild-type skin phenotype (15). Histopathological studies in these mice have demonstrated that the chronic inflammatory reaction is a foreign body response, with extreme sebaceous gland hypoplasia in SCD1-deficient animals resulting in hair fiber perforation of the follicle base and a foreign body response to fragments of hair fiber in the dermis (10).

Inflammation is recognized to play a major role in all stages of atherogenesis (27), and plasma markers of systemic inflammation are predictive for cardiovascular events in humans (28, 29). Indeed, standard preventive drug therapies such as aspirin and statins are known to have antiinflammatory properties and have been shown to be most beneficial in individuals with elevated inflammatory markers at baseline, even in those with relatively low serum cholesterol levels (30).

In the LDLR-deficient mouse model, used by several groups to study the link between chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis (31, 32), plasma markers of systemic inflammation increase in response to dietary cholesterol, and these markers are associated with increased lesion area independent of plasma lipoprotein levels (33). Our observations of increased plasma IL-6, a marker of systemic inflammation that is associated with atherosclerosis (28), sICAM-1, an adhesion molecule that is elevated in serum of patients with inflammatory skin disorders (16, 17), and IL-1β and IL-12p70, pro-inflammatory cytokines known to be elevated in psoriatric lesional skin (18, 19), suggest that chronic inflammation of the skin may be contributing to the proatherogenic profile of SCD-1 deficient mice. During an inflammatory response, HDL particles are known to become depleted in apoA-I, apoA-II, and PON1 and enriched in SAA, a liver-derived protein increased by western diets and correlated with lesion area in LDLR-deficient mice (21, 33). Our results show that absence of SCD1 has a proatherogenic effect on HDL composition.

Atherosclerotic lesion size and macrophage cholesterol efflux are not altered in LDLR-deficient mice transplanted with bone marrow from SCD1-deficient mice. These observations, in addition to the lack of altered LPS-induced inflammatory response in SCD1-deficient peritoneal macrophages, suggest that macrophage SCD1 does not play a significant role in atherogenesis in this model. However, it should be noted that these results are from early lesions only and a longer term study is needed of SCD1 in lesion macrophages.

The SCD1-deficient mouse model affords a unique opportunity to compare and contrast directly the effects of an antiatherogenic metabolic profile with proinflammatory pathways. In this instance, proinflammatory pathways overcome the favourable metabolic profile. However, significant unanswered questions remain regarding possible atherogenic effects of circulating lipoproteins or tissue lipids with increased saturated fatty acids (SFA) or decreased monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), as shown in SCD1-deficient mice (2, 34).

The relevance of these findings to the development of SCD inhibitors for treatment of the metabolic syndrome in humans is unclear. Observational studies in humans have shown an association between increased indices of SCD activity and components of the metabolic syndrome (35–37), inflammatory markers (38), and potentially coronary heart disease (39), suggesting that the atherogenic inflammation observed in this mouse model of SCD1 deficiency may not extend to humans with reduced SCD1 activity. The findings in this study represent the effects of long-term complete SCD1 deficiency in all tissues in mice. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) may also be expected to result in near complete deficiency of SCD1 expression in some extra-hepatic tissues (40), which could lead to atherogenic inflammation in rodent models similar to that observed here. By contrast, pharmaceutical compounds are generally not used at levels that would cause complete inhibition of the target enzyme through a 24-hour cycle, and would not be distributed throughout all tissues in the body.

While this manuscript was in review, two different studies reported on the relationship between atherosclerosis and SCD1 deficiency mediated by ASOs. Both groups treated mice with identical SCD1-targeted ASOs, but the experiments yielded different results: increased atherosclerosis in the Ldlr−/− Apob100/100 model (41) and reduced atherosclerosis in the chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) model (42). One clue to the discrepancy could be model-specific effects on HDL-cholesterol levels, as SCD1 deficiency is accompanied by a ~50% reduction of HDL-cholesterol levels in the dyslipidemic Ldlr−/− Apob100/100 model (41), a change in HDL expected to be associated with increased atherosclerosis (43). However, ASO-mediated SCD1 deficiency in the CIH model is accompanied by an atheroprotective ~20% increase in HDL-cholesterol levels (42). Our results indicate that in the absence of changes in HDL-cholesterol levels, complete and chronic SCD1 deficiency is likely to exacerbate atherosclerosis.

These studies now provide strong support for the role of chronic inflammation in promoting atherosclerosis, even in the presence of antiatherogenic biochemical and metabolic characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Julie Chow Low, Nick Nation, William T. Gibson, Elaine Fernandes and Emmanuelle Vallez for their expert technical assistance with general histology, skin histopathology, image analysis, Luminex assays and lipoprotein analysis, respectively. We also thank Michael D. Winther at Xenon Pharmaceuticals for insightful comments and discussion. Special thanks to Mark Wang, Kevin Cheng and the staff of the Wesbrook Animal Unit and the Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics Transgenic Core Facility for expert care of mice. M.L.E.M., M.J.C. and M.R.H. designed research; M.L.E.M., M.V.E., R.B.H, N.B., P.R., A.K., H.H., B.W.C.W., M.A.P, T.J.C.vB., and C.F. performed research; M.L.E.M., M.V.E., B.M.M, B.S. and C.F. analyzed data; M.L.E.M. and M.R.H. wrote the paper.

Sources of Funding: M.L.E.M. was the recipient of a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Canada Graduate Scholarship. M.V.E. is an Established Investigator of The Netherlands Heart Foundation (grant 2007T056) and further support was obtained from The Netherlands Organization of Scientific Research (VIDI grant 917.66.301 (M.V.E.). M.R.H. holds a Canada Research Chair in Human Genetics and is a University Killam Professor.

Footnotes

Disclosure: M.R.H is a founder and serves on the board of directors of Xenon Pharmaceuticals.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is an un-copyedited author manuscript that was accepted for publication in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, copyright The American Heart Association. This may not be duplicated or reproduced, other than for personal use or within the “Fair Use of Copyrighted Materials” (section 107, title 17, U.S. Code) without prior permission of the copyright owner, The American Heart Association. The final copyedited article, which is the version of record, can be found at http://atvb.ahajournals.org/. The American Heart Association disclaims any responsibility or liability for errors or omissions in this version of the manuscript or in any version derived from it by the National Institutes of Health or other parties.

References

- 1.Miyazaki M, Ntambi JM. Role of stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase in lipid metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;68:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(02)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyazaki M, Kim YC, Gray-Keller MP, Attie AD, Ntambi JM. The biosynthesis of hepatic cholesterol esters and triglycerides is impaired in mice with a disruption of the gene for stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30132–30138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landau JM, Sekowski A, Hamm MW. Dietary cholesterol and the activity of stearoyl CoA desaturase in rats: evidence for an indirect regulatory effect. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1345:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Man WC, Miyazaki M, Chu K, Ntambi J. Colocalization of SCD1 and DGAT2: implying preference for endogenous monounsaturated fatty acids in triglyceride synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1928–1939. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600172-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ntambi JM, Miyazaki M, Stoehr JP, Lan H, Kendziorski CM, Yandell BS, Song Y, Cohen P, Friedman JM, Attie AD. Loss of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 function protects mice against adiposity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11482–11486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132384699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen P, Miyazaki M, Socci ND, Hagge-Greenberg A, Liedtke W, Soukas AA, Sharma R, Hudgins LC, Ntambi JM, Friedman JM. Role for stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 in leptin-mediated weight loss. Science. 2002;297:240–243. doi: 10.1126/science.1071527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald MLE, Singaraja RR, Bissada N, Ruddle P, Watts R, Karasinska JM, Gibson WT, Fievet C, Vance JE, Staels B, Hayden MR. Absence of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 ameliorates features of the metabolic syndrome in LDLR-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:217–229. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700478-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Getz GS, Reardon CA. Diet and murine atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:242–249. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201071.49029.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Eilertsen KJ, Ge L, Zhang L, Sundberg JP, Prouty SM, Stenn KS, Parimoo S. Scd1 is expressed in sebaceous glands and is disrupted in the asebia mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:268–270. doi: 10.1038/15446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundberg JP, Boggess D, Sundberg BA, Eilertsen K, Parimoo S, Filippi M, Stenn K. Asebia-2J (Scd1(ab2J)): a new allele and a model for scarring alopecia. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2067–2075. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:883–893. doi: 10.1172/JCI116663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singaraja RR, Fievet C, Castro G, James ER, Hennuyer N, Clee SM, Bissada N, Choy JC, Fruchart J, McManus BM, Staels B, Hayden MR. Increased ABCA1 activity protects against atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:35–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI15748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan-Merchant N, Penumetcha M, Meilhac O, Parthasarathy S. Oxidized fatty acids promote atherosclerosis only in the presence of dietary cholesterol in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. J Nutr. 2002;132:3256–3262. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown WR, Hardy MH. A hypothesis on the cause of chronic epidermal hyperproliferation in asebia mice. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:74–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1988.tb00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oran A, Marshall JS, Kondo S, Paglia D, McKenzie RC. Cyclosporin inhibits intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression and reduces mast cell numbers in the asebia mouse model of chronic skin inflammation. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Pità O, Ruffelli M, Cadoni S, Frezzolini A, Biava GF, Simom R, Bottari V, De Sanctis G. Psoriasis: comparison of immunological markers in patients with acute and remission phase. J Dermatol Sci. 1996;13:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(96)00517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalzick L, Kleinheinz A, Neuber K, Weichenthal M, Köhler I, Ring J. Elevated serum levels of soluble adhesion molecules ICAM-1 and ELAM-1 in patients with severe atopic eczema and influence of UVA1 treatment. Dermatology. 1995;190:14–18. doi: 10.1159/000246627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper KD, Hammerberg C, Baadsgaard O, Elder JT, Chan LS, Taylor RS, Voorhees JJ, Fisher G. Interleukin-1 in human skin: dysregulation in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95:24S–26S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12505698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yawalkar N, Karlen S, Hunger R, Brand CU, Braathen LR. Expression of interleukin-12 is increased in psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:1053–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kontush A, Chapman MJ. Functionally defective high-density lipoprotein: a new therapeutic target at the crossroads of dyslipidemia, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:342–374. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durrington PN, Mackness B, Mackness MI. Paraoxonase and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:473–480. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardardóttir I, Kunitake ST, Moser AH, Doerrler WT, Rapp JH, Grünfeld C, Feingold KR. Endotoxin and cytokines increase hepatic messenger RNA levels and serum concentrations of apolipoprotein J (clusterin) in Syrian hamsters. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1304–1309. doi: 10.1172/JCI117449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Hao M, Luo Y, Liang CP, Silver DL, Cheng C, Maxfield FR, Tall AR. Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase Inhibits ATP-binding Cassette Transporter A1-mediated Cholesterol Efflux and Modulates Membrane Domain Structure. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5813–5820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA, Heiss G, Sorlie PD, Catellier D, Patsch W. Coronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol levels, triglycerides, lipoprotein(a), apolipoproteins A-I and B, and HDL density subfractions: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2001;104:1108–1113. doi: 10.1161/hc3501.095214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grundy SM. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:2696–2698. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020650.86137.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101:1767–1772. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rossouw JE, Siscovick DS, Mouton CP, Rifai N, Wallace RB, Jackson RD, Pettinger MB, Ridker PM. Inflammatory biomarkers, hormone replacement therapy, and incident coronary heart disease: prospective analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study. JAMA. 2002;288:980–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.8.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, Genest J, Gotto AMJ, Kastelein JJP, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ. Rosuvastatin to Prevent Vascular Events in Men and Women with Elevated C-Reactive Protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nofer J, Bot M, Brodde M, Taylor PJ, Salm P, Brinkmann V, van Berkel T, Assmann G, Biessen EAL. FTY720, a synthetic sphingosine 1 phosphate analogue, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Circulation. 2007;115:501–508. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.641407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cyrus T, Tang LX, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA, Praticò D. Lipid peroxidation and platelet activation in murine atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2001;104:1940–1945. doi: 10.1161/hc4101.097114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis KE, Kirk EA, McDonald TO, Wang S, Wight TN, O’Brien KD, Chait A. Increase in serum amyloid a evoked by dietary cholesterol is associated with increased atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2004;110:540–545. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136819.93989.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Attie AD, Krauss RM, Gray-Keller MP, Brownlie A, Miyazaki M, Kastelein JJ, Lusis AJ, Stalenhoef AF, Stoehr JP, Hayden MR, Ntambi JM. Relationship between stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity and plasma triglycerides in human and mouse hypertriglyceridemia. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1899–1907. doi: 10.1194/jlr.m200189-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stumvoll M. Control of glycaemia: from molecules to men. Minkowski Lecture 2003. Diabetologia. 2004;47:770–781. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan DA, Lillioja S, Milner MR, Kriketos AD, Baur LA, Bogardus C, Storlien LH. Skeletal muscle membrane lipid composition is related to adiposity and insulin action. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2802–2808. doi: 10.1172/JCI118350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon JA, Fong J, Bernert JTJ. Serum fatty acids and blood pressure. Hypertension. 1996;27:303–307. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersson H, Basu S, Cederholm T, Risérus U. Serum fatty acid composition and indices of stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity are associated with systemic inflammation: longitudinal analyses in middle-aged men. Br J Nutr. 2007:1–4. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507871674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heffernan AGA. Fatty Acid Composition of Adipose Tissue in Normal and Abnormal Subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1964;15:5–10. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/15.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutierrez-Juarez R, Pocai A, Mulas C, Ono H, Bhanot S, Monia BP, Rossetti L. Critical role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1) in the onset of diet-induced hepatic insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1686–1695. doi: 10.1172/JCI26991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown JM, Chung S, Sawyer JK, Degirolamo C, Alger HM, Nguyen T, Zhu X, Duong M, Wibley AL, Shah R, Davis MA, Kelley K, Wilson MD, Kent C, Parks JS, Rudel LL. Inhibition of Stearoyl-Coenzyme A Desaturase 1 Dissociates Insulin Resistance and Obesity From Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2008;118:1467–1475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savransky V, Jun J, Li J, Nanayakkara A, Fonti S, Moser AB, Steele KE, Schweizer MA, Patil SP, Bhanot S, Schwartz AR, Polotsky VY. Dyslipidemia and Atherosclerosis Induced by Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia Are Attenuated by Deficiency of Stearoyl Coenzyme A Desaturase. Circ Res. 2008;103:1173–1180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tangirala RK, Tsukamoto K, Chun SH, Usher D, Puré E, Rader DJ. Regression of atherosclerosis induced by liver-directed gene transfer of apolipoprotein A-I in mice. Circulation. 1999;100:1816–1822. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.17.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.