Abstract

Molecular mechanisms involved in epileptogenesis in the developing brain remain poorly understood. The gene array approach could reveal some of the factors involved by allowing the identification of a broad scale of genes altered by seizures. In this study we used microarray analysis to reveal the gene expression profile of the laser microdissected hippocampal CA1 subregion one week after kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus (SE) in 21-day-old rats, which are developmentally roughly comparable to juvenile children. The gene expression analysis with the Chipster software generated a total of 1592 differently expressed genes in the CA1 subregion of KA-treated rats compared to control rats. The KEGG database revealed that the identified genes were involved in pathways such as oxidative phosporylation (26 genes changed), and long-term potentiation (LTP; 18 genes changed). Also genes involved in Ca2+ homeostasis, gliosis, inflammation, and GABAergic transmission were altered. To validate the microarray results we further examined the protein expression for a subset of selected genes, glial fibrillary protein (GFAP), apolipoprotein E (apo E), cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1), Purkinje cell protein 4 (PEP-19), and interleukin 8 receptor (CXCR1), with immunohistochemistry, which confirmed the transcriptome results. Our results showed that SE resulted in no obvious CA1 neuronal loss, and alterations in the expression pattern of several genes during the early epileptogenic phase were comparable to previous gene expression studies of the adult hippocampus of both experimental epileptic animals and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). However, some changes seem to occur after SE specifically in the juvenile rat hippocampus. Insight of the SE-induced alterations in gene expression and their related pathways could give us hints for the development of new target-specific antiepileptic drugs that interfere with the progression of the disease in the juvenile age group.

Introduction

Epilepsy, one of the most common neurological disorders affecting up to 1% of the population, is caused by a number of both unknown and known factors such as trauma, hypoxia, postnatal insults, and status epilepticus (SE) [1], [2]. In experimental animal models, SE can be induced by different chemoconvulsants, e.g. kainic acid (KA), which induces region-specific neuropathological changes in the hippocampus comparable to those of patients with chronic temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) [3], [4], [5]. In addition to region-specificity, earlier studies indicate that the extent and localization of KA-induced hippocampal damage is age-specific, the immature rats (<21-day old) having minor or even no obvious damage [6], [7], [8], while degeneration of CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons and hilar interneurons have frequently been documented in adult rats [3], [6], [9].

The acute seizure-induced excitotoxic insult is known to initiate a process of changes defined as epileptogenesis, which finally leads to spontaneous seizures, i.e. epilepsy in the majority of adult rats [1], [10], [11]. In immature rats, the appearance of spontaneous seizures and other long-term consequences seems to be less severe [6], [10], [12]. In spite of numerous studies focusing on epileptogensis both in adult and immature brain, its cellular and molecular mechanisms have remained largely undiscovered. In search for factors involved in epileptogenesis in the hippocampus, the gene expression approach using microarrays has recently been successfully applied. The results of these studies suggest that the expression of a number of genes is altered in the adult rat hippocampus after SE induced by KA [13], [14], pentylenetetrazol [15], and electrical stimulation [16], [17]. The results of more detailed gene microarray studies carried out in specimen microdissected from the selected hippocampal sub-regions have revealed that the alterations are not uniform, but region-specifically distributed in the hippocampus [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. It can be assumed that the targeted gene array approach reveals more exactly the region-specific pathways activated in the course of epileptogenesis. Furthermore, as seizure-induced pathology seems to be age-specific, there could also be age-specific differences in the pathways altered by seizures, which could elucidate in more detail the postulated differences in epileptogenesis between the immature and mature brain. However, to our knowledge, there is only one earlier microarray study focusing on gene expression in normal immature rats (P3) [21], and no earlier studies after experimental SE either in immature or juvenile animals.

In our current study, we specifically focused on juvenile, 21-day-old (P21) rats, in which KA-induced SE leads to selective damage of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons while saving neurons of the other sub-regions [7], [23]. We searched for alterations in the gene expression pattern during the early epileptogenetic phase, i.e. one week after SE, and compared the results with those of age-matched control rats. To detect specifically changes in the CA1 pyramidal neurons, we used the laser-capture microdissection technique that allows the precise isolation of the region of interest. The transcriptome was analyzed by using gene expression microarrays which generated differentially expressed genes, and the results of certain, selected genes of interest were confirmed at the protein level using immunohistochemistry.

Materials and Methods

Kainate treatment of the rats

P21 Sprague–Dawley male rats were chosen for these experiments (n = 4, in both the control and KA-treated groups). A single dose of KA (Tocris Cookson Ltd., Avomouth, UK) (7 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally to the rats, which were thereafter carefully followed up to detect signs of seizures, as earlier described in detail [23]. Within 15 min after the injection, rats first showed deep breathing and increased salivation followed by scratching with further progression to rearing and generalized tonic/clonic seizures within 50–60 min, which lasted for 2–3 h. After a follow-up for further 2 h after the cessation of behavioral seizures, rats were taken back to their cages, and sacrificed 7 days after the KA injection. Control rats received the same volume of 0.9% NaCl as those of KA-treated, but were otherwise treated as the KA-injected rats described above. About 80% of KA-treated animals developed SE, and only animals which experienced SE were included in this study. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the European Community Council Directives 86/609/EEC, and had the approval of the Office of the Regional Government of Western Finland. Using our protocol the mortality of rats was zero. All efforts were made to minimize the pain, discomfort, and number of experimental animals.

Tissue collection

After decapitation, brains where dissected into halves. One half of the brain was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen for the microarray study, and the other half was submerged in 4% paraformadehyde (PFA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) for immunocytochemistry and Fluoro-Jade B (FJB) staining. For the transcriptome studies, the liquid nitrogen-frozen brains were cut into 40 µm coronal slices onto PALM membrane slides (PALM Microlaser Technologies GmbH, Germany), and stored at −80°C. To visualize the various hippocampal subregions, all slices prepared from the hippocampi of control and KA-treated rats were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and the hippocampal pyramidal CA1 cell layer of the control and KA-treated rats was cut using the laser capture micro-dissection (LCM) technology, and catapulted on PALM adhesive caps (see Fig. 1D). Eight consecutive sections obtained from each animal were used to maximize the yield and quality of the extracted total RNA and to circumvent the need of additional PCR-amplification steps for the subsequent microarray labelling of the RNA-samples.

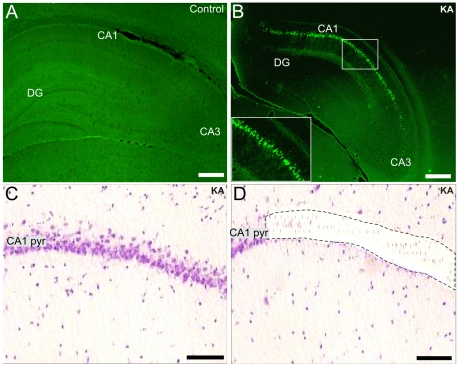

Figure 1. Neuronal CA1 pyramidal cell damage and the region-specific laser microdisecction one week after SE.

Fluoro-Jade B staining of a representative control (A) and KA-treated rat (B) one week after SE. Fig.1B shows positively stained CA1 pyramidal neurons (see also the inset in B). Figs.1C and D show hematoxylin-eosin staining of the CA1 pyramidal layer of a KA-treated rat before and after laser microdissection, respectively. Scale bars: A and B: 200 µm; C and D: 75 µm. Abbreviations: CA1 pyr, stratum pyramidale of CA1; DG, dentate gyrus; KA, kainic acid.

RNA isolation and assessment of the RNA quality

The total RNA of the LCM samples was isolated using the EPICENTRE Array Pure™ Nano – scale RNA Purification Kit (Madison, USA). The RNA solution was treated with the DNase and RNase inhibitor (ScriptGuard™, included in the Array Pure™ Nano Kit), and the quality and approximate quantity of the resulting RNA were determined spectrofotometrically using Nanodrop-1000 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Wilmington, USA), and a capillary electrophoresis system (Experion, Bio-Rad).

Microarray analysis

Total RNA (100 ng), isolated from LCM-samples that were dissected from each individual experimental animal separately as described above, was amplified, labeled, and hybridized according to the manufacturers' protocols (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). In brief, biotin-labeled cRNA was prepared by a linear amplification method using the Illumina® TotalPrep™ RNA Amplification Kit. After the first and second strand synthesis, the cDNA served as the template for an in vitro transcription reaction to produce the biotinylated, amplified target cRNA (750 ng) used for the Illumina RatRef-12 Expression BeadChip arrays with each sample hybridized on separate arrays. After hybridization and washing the arrays were scanned and read by the Illumina Bead Array Reader, and the data was extracted by using the Illumina Bead Studio (version 3). All microarray data was deposited in ArrayExpress with the accession number E-TABM-881, according to the guidelines of MIAME by the European Bioinformatics Institute (www.ebi.ac.uk/microrarray_as/).

Microarray data analysis

Microarray data analysis (Chipster software v1.1.0, CSC, Finland) was applied to identify those genes that had statistically significant differences in their expression between the groups. The outliers were excluded based on their expression intensity within a group, and those samples did not affect the outcome of the further analysis. In order to distinguish the two groups under assessment, phenodata was created, and the normalization of genes was made by the quantile normalization method (which makes the expression value to follow the same distribution on all chips), with no production of flags on the RatRef-12 chip type, beadstudio version 3, and by using “Probe ID” as identifier. In order to discard unreliable and uninformative data points, the filtering process was carried out, and the group of genes that have a corrected p-value smaller than the cut-off p-value (0.05) passed the statistical “two group test”. The filtering was performed by using the empirical Bayes method with Benjamin and Hochberg post hoc test, and the contrasts were created by using the Limma R/Bioconductor (www.bioconductor.org). Finally, the data was clustered by using the non-hierarchical K-means clustering for genes, which identifies k points that function as cluster centers. Each data point was then assigned to one of these centers in a way that minimizes the sum of the distances between all points and their centers [24]. The pathway analysis was performed by ‘Gene set test’, which analyzes the statistical significance of a set of genes simultaneously ranked by p-value and generates the KEGG categories (Chipster manual). The KEGG pathway maps and the gene ontology classification were obtained using the DAVID Bioinformatics Resources from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), NIH (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was carried out to verify the gene array results of certain, selected genes of interest. For that, brains of the KA-injected and their respective saline controls were used for the immunohistochemical study, which was carried out as previously described in detail [25]. After fixation in 4% PFA in PBS (pH 7.4), brains were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS at +4°C, frozen, and thereafter kept at −80°C until used. For the immunostaining, brains were cryosectioned in 30 µm slices, collected in PBS (pH 7.4), and processed in a free-floating system. Slices were first incubated in the blocking solution (BS) containing 2% bovine serum albumin, 2% goat serum, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 7.4) for 1 h at room temperature, and thereafter with the primary antibodies for 24–48 h at +4°C in BS at the following dilutions: glial fibrillary acid (GFAP; 1:3000, Sigma, St. Louis, USA), apolipoprotein E (apo E; 1∶1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1; 1∶1000, Abcam), Purkinje cell protein 4 (PEP-19; 1∶500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and interleukin 8 receptor (CXCR1; 1∶1000, Abcam). After washing in PBS, slices were incubated with the biotin-conjugated secondary antibody (1∶4000) in BS, rinsed with PBS, and incubated with the avidin-peroxidase conjugate (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) in BS for 1 h at room temperature. The staining was detected using 3,3-diaminobenzidinetetrahydrochloride (Sigma) as a chromogen, and further processed as earlier described [25]. Alternatively, Alexa 568 (1∶2000, Invitrogen) was used as a secondary antibody. In each experiment, KA-treated and control brains of the same age were processed simultaneously, and two to three slices from each brain, in which the primary antibody was omitted but which were otherwise treated as indicated above, served as negative control. Preparations were examined with a Leica DM R microscope (Heerbrugg, Switzerland) under the bright field or fluorescence optics.

Fluoro-Jade B staining

FJB, an anionic fluorescein with excitation peaks at 362 and 390 nm and the emission peak at 550 nm, is a marker of neuronal degeneration regardless of the nature of the injury [26]. FJB staining was carried out in brain slices prepared from 4% PFA-fixed brains 7 days after the KA injection. Brain slices (20 µm thick) were cut and mounted on gelatin-coated glasses. The FJB staining was carried out as previously described in detail [8] with minor modifications. Briefly, brain slices were rehydrated with alcohol series, transferred for 2–5 min to 0.06% potassium permanganate (KMnO4), washed with distilled water, and transferred to 0.001% FJB solution for 30 min. After that, slides were washed, dried, cleared in xylene, coverslipped with mounting medium, and examined with the Leica DM R microscope under fluorescence filters.

Hematoxylin-Eosin staining

The hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed using basic histological staining protocols. Briefly, brain slices (40 µm slices on PALM membrane slides) were stained with Mayer's Hematoxylin, dehydrated in ethanol series, and cleared in xylene before using the LCM.

Results

Selective neuronal damage after SE in the CA1 region

The extent of regional hippocampal neuronal damage after KA-induced SE was assessed using FJB staining. Fig. 1A shows a representative image of the hippocampus of a P21 saline-injected control rat, in which no positively FJB-stained neurons were detected. In contrast, numerous FJB-stained pyramidal neurons appeared exclusively in the CA1 region one week after KA-induced SE (Fig. 1B). The hematoxylin-eosin staining (Fig. 1C) accurately indicated the CA1 pyramidal cell layer, which did not show any obvious neuronal loss. This region was microdissected with laser (Fig. 1D), and further processed to extract the total RNA.

Microarray data analysis profile

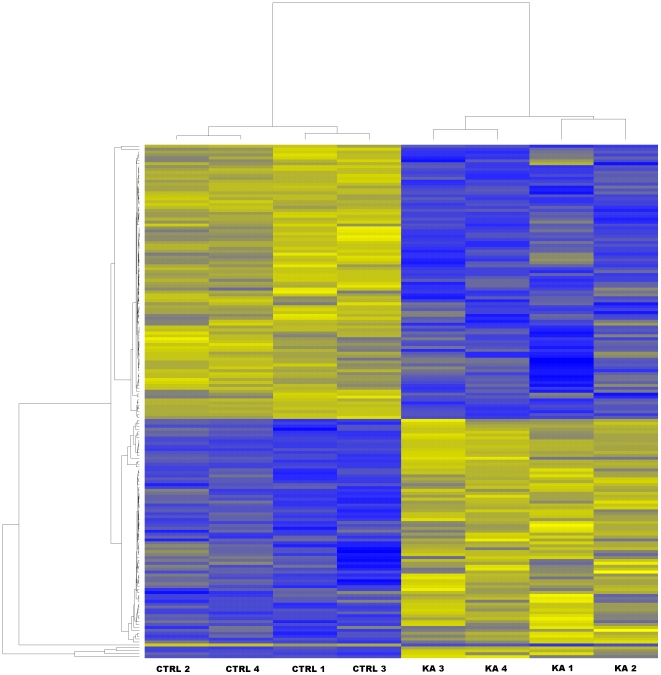

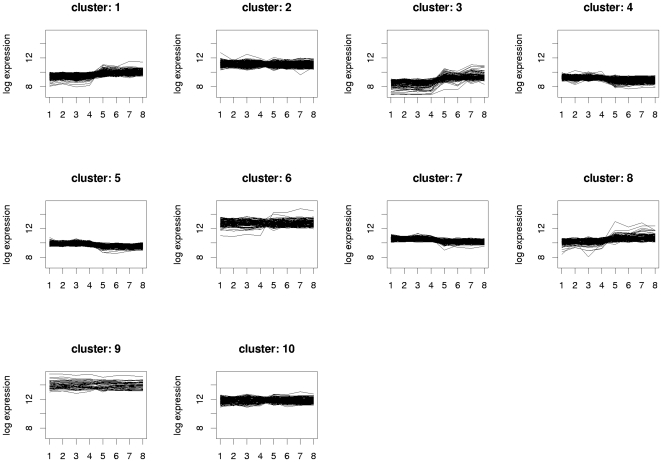

Transcriptional responses of the CA1 region with the subsequent Illumina microarray analysis returned a total of 1592 genes that were statistically differentially expressed in KA-treated as compared to the age-matched control animals with the filter cut-off set at the 2-fold difference in the gene expression level with the p-value <0.05. The contrasts in the gene expression levels that were revealed by the data analysis between the KA-treated and control animals were visualized by a heatmap (Fig. 2), in which the yellow colour indicated up-regulation, and the blue colour down-regulation in the contrasted samples. The heatmap of the samples showed that the contrasting algorithm divided the samples in two distinct groups with the replicates of the control samples in one group (n = 4), and the samples from KA-treated rats in the other group (n = 4) (Fig. 2). The low variation between the samples from KA-treated rats may be due to the fact that all the treated animals included in this study experienced SE, and showed concomitant neurodegeneration in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer. This may have contributed to the high correlations between the biological samples within the groups (Fig. 2), that in turn resulted in a relatively high number of genes with a statistically significant difference in their expression. Further data mining of the transcriptome analysis included K-nearest neighbour classification. Using the K-means method the genes were classified in 10 different clusters representing the functionally distinct gene expression patterns that visualize the full extraction of the biologically significant phenomena in the data (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. Heatmap of the samples assayed by microarrays.

The figure illustrates the highest contrasts between the samples that were clustered by similarity in the gene expression levels. The control samples were clearly distinguished as a coherent group separate from the samples of KA-treated rats. Controls showed up-regulation of a specific set of genes (as indicated by yellow) in contrast to the samples of KA-treated rats presenting down-regulated levels of the same genes (as indicated by blue), while a distinct set of genes were down-regulated in the control samples, and up-regulated in the samples of KA-treated rats. The clustering of the genes (gene names omitted) is shown in the left vertical panel, and the clustering of the samples is indicated in the top horizontal panel of the figure. Abbreviations: CTRL, control rat; KA, kainic acid-treated rat.

Figure 3. K-means clustering of the genes by their expression pattern.

The K-means clustering method is visualized with the 10 distinct clusters as plotted by the log of the gene expression level of all the genes analyzed by the microrarrays. Our interest was to reveal the major differences between the KA-treated and control rats. In the figure the samples of the control and KA-treated rats are indicted by the numbers 1–4 and 5–8, respectively, in the x-axis. Abbreviation: KA, kainic acid.

Genes related to pathways

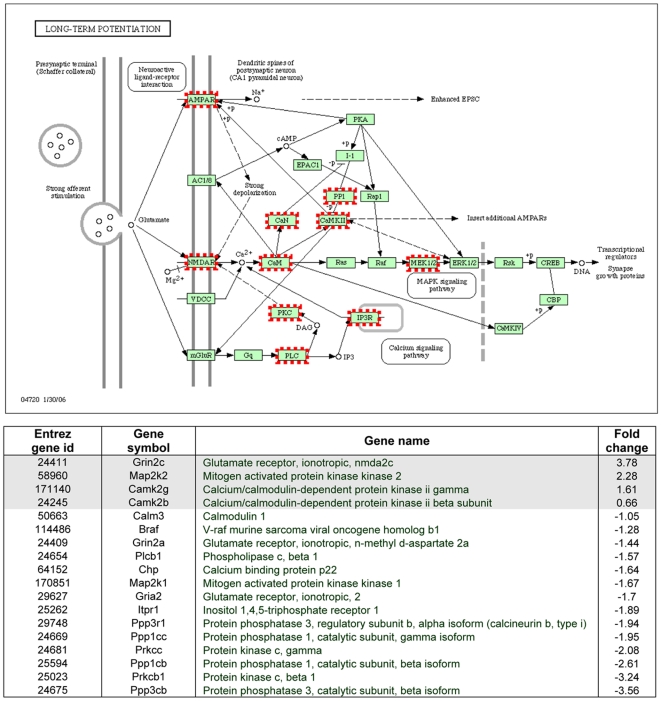

The subsequent KEGG-test for the probe set over-representation analysis revealed the 15 significantly (p<0.05) changed KEGG-pathways in response to KA-treatment (see Materials and Methods and Table 1). Some of the most pronouncedly affected pathways were involved in oxidative phosphorylation (26 genes, of which 19 down-regulated; Fig. S1), ribosomal pathway (19 genes, of which 18 up-regulated; Fig. S2), long-term potentiation (LTP; 18 genes, of which 14 down-regulated; Fig. 4), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signalling pathway (13 genes, of which 9 down-regulated; Fig. S3). The gene ontology classification shows corresponding gene changes grouped by their molecular function (Table 2). Among the statistically differentially expressed genes, changes were also found in the expression of genes involved in the pathways related to neuronal damage, Ca2+ regulation, gliosis, inflammation, synaptic transmission, and cytoskeletal structure (Tables 3 and 4). These changes were analyzed in more detail (as follows).

Table 1. KEGG-test for over-representation of the pathways in response to KA-treatment.

| Entry number | Term or pathway | P Value | Odds Ratio | Count | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

| rno00190 | Oxidative phosphorylation | <0.01 | 3.99 | 26 | 7 | 19 |

| rno03050 | Proteasome | <0.01 | 7.36 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| rno04070 | Phosphatidylinositol signaling system | <0.01 | 3.26 | 16 | 3 | 13 |

| rno03010 | Ribosome | <0.01 | 3.07 | 19 | 18 | 1 |

| rno04720 | Long-term potentiation | <0.01 | 2.99 | 18 | 4 | 14 |

| rno00100 | Biosynthesis of steroids | <0.01 | 5.31 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| rno00562 | Inositol phosphate metabolism | <0.01 | 3.49 | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| rno05010 | Alzheimer's disease | 0.01 | 4.21 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| rno03060 | Protein export | 0.01 | 8.77 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| rno04370 | VEGF signaling pathway | 0.02 | 2.22 | 13 | 4 | 9 |

| rno04540 | Gap junction | 0.02 | 2.01 | 18 | 7 | 11 |

| rno04912 | GnRH signaling pathway | 0.02 | 1.94 | 17 | 7 | 10 |

| rno04730 | Long-term depression | 0.03 | 1.98 | 14 | 2 | 12 |

| rno00260 | Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism | 0.03 | 2.71 | 8 | 4 | 4 |

| rno00910 | Nitrogen metabolism | 0.05 | 3.75 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

Figure 4. The KEGG-derived long-term potentiation pathway.

The concerted action of glutamate on NMDA and AMPA receptors in CA1 pyramidal neurons is illustrated in this pathway, as well as the activation of different subpathways. The genes activated on the microarray are encircled. The table below shows the entire list of up- or down-regulated genes related to LTP on the microarray. Abbreviations: AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate.

Table 2. Classification of the gene ontology by the molecular function as revealed by the microarray study in juvenile rats after SE.

| Entry number | Term | Number of altered genes |

| MF00042 | Nucleic acid binding | 406 |

| MF00213 | Non-receptor serine/threonine protein kinase | 213 |

| MF00262 | Non-motor actin binding protein | 126 |

| MF00075 | Ribosomal protein | 94 |

| MF00101 | Guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor | 92 |

| MF00250 | Serine protease inhibitor | 81 |

| MF00123 | Oxidoreductase | 67 |

| MF00141 | Hydrolase | 65 |

| MF00072 | Translation initiation factor | 65 |

| MF00082 | Transporter | 57 |

| MF00107 | Kinase | 56 |

| MF00267 | Membrane traffic protein | 52 |

| MF00137 | Glycosyltransferase | 47 |

| MF00264 | Microtubule family cytoskeletal protein | 45 |

| MF00097 | G-protein | 45 |

| MF00211 | Kinase activator | 43 |

| MF00170 | Ligase | 37 |

| MF00108 | Protein kinase | 37 |

| MF00283 | Ubiquitin-protein ligase | 36 |

| MF00113 | Phosphatase | 35 |

| MF00021 | Neuropeptide | 34 |

| MF00255 | Non-motor microtubule binding protein | 34 |

| MF00126 | Dehydrogenase | 33 |

| MF00051 | Helicase | 27 |

| MF00239 | Phosphatase inhibitor | 25 |

| MF00094 | Kinase modulator | 25 |

| MF00243 | DNA helicase | 25 |

| MF00077 | Chaperone | 23 |

| MF00270 | Membrane traffic regulatory protein | 22 |

| MF00268 | Vesicle coat protein | 22 |

| MF00236 | Exoribonuclease | 20 |

| MF00218 | Calmodulin related protein | 19 |

| MF00269 | SNARE protein | 14 |

| MF00139 | Acyltransferase | 13 |

| MF00121 | Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | 13 |

| MF00110 | Nucleotide kinase | 13 |

| MF00119 | Synthase | 12 |

| MF00147 | Deaminase | 11 |

| MF00116 | Nucleotide phosphatase | 11 |

| MF00150 | Glycosidase | 11 |

| MF00263 | Other actin family cytoskeletal protein | 9 |

| MF00088 | Apolipoprotein | 9 |

| MF00161 | Decarboxylase | 8 |

| MF00155 | Phosphorylase | 5 |

| MF00199 | Storage protein | 5 |

| MF00200 | Myelin protein | 5 |

| MF00115 | Carbohydrate phosphatase | 4 |

| MF00007 | Interferon receptor | 3 |

Table 3. Differential expression of genes in the CA1 region of KA-treated rats compared to control rats: genes associated with neuronal damage, calcium-binding, gliosis and inflammation.

| Gene databank accession no. | Gene name | Gene symbol | Fold change |

| Genes associated with neuronal damage | |||

| NM_053812 | Bcl2-antagonist killer 1 | Bak1 | +3.31 |

| NM_022698 | Bcl2-associated death promoter | Bad | +1.10 |

| NM_053586 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5b | Cox5b | +1.03 |

| NM_182819 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 7b | Cox7b | −1.07 |

| NM_145783 | Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 5a | Cox5a | −1.12 |

| NM_017309 | Protein phosphatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha isoform (calcineurin B, type I) | Ppp3r1 | −1.94 |

| Genes associated with calcium-binding | |||

| NM_013002 | Purkinje cell protein 4 | Pcp4 | +13.3 |

| XM_215607 | S100 calcium binding protein A13 | S100a13 | +7.20 |

| XM_579178 | S100 calcium binding protein A1 | S100a1 | +5.10 |

| XM_342291 | S100 calcium binding protein A16 | S100a16 | +4.49 |

| NM_013191 | S100 calcium binding protein B | S100b | +3.34 |

| NM_133605 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II gamma | Camk2g | +1.61 |

| NM_021739 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II beta | Camk2b | +0.66 |

| NM_017326 | Calmodulin 2 | Calm2 | −1.05 |

| NM_031662 | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 1, alpha | Camkk1 | −1.06 |

| XM_579543 | Calmodulin 1 | Calm1 | −1.28 |

| NM_017195 | Growth associated protein 43 | Gap43 | −1.89 |

| NM_031984 | Calbindin 1 | Calb1 | −4.99 |

| Genes associated with gliosis and inflammation | |||

| XM_579387 | Glial fibrillary acid protein | Gfap | +13.7 |

| NM_012823 | Annexin A3 | Anxa3 | +7.84 |

| NM_053960 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 | Ccr5 | +6.51 |

| NM_017320 | Cathepsin S | Ctss | +6.47 |

| NM_013069 | CD74 antigen (invariant polypeptide of major histocompatibility complex, class II antigen-associated) | Cd74 | +6.10 |

| NM_198740 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DM beta | Hla-dmb | +5.84 |

| NM_138828 | Apolipoprotein E | Apoe | +3.76 |

| NM_012512 | Beta-2 microglobulin | B2m | +3.75 |

| NM_012837 | Cystatin C | Cst3 | +3.58 |

| NM_017232 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | Ptgs2 | +2.48 |

| NM_031560 | Cathepsin K | Ctsk | −3.21 |

| NM_019310 | Interleukin 8 receptor, alpha | Il8ra | −6.08 |

Table 4. Differential expression of genes in the CA1 region of KA-treated rats compared to control rats: genes associated with synaptic transmission, voltage-gated channels, ribosomes and cytoskeleton.

| Gene databank accession no. | Gene name | Gene symbol | Fold change |

| Genes associated with synaptic transmission | |||

| NM_012575 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA 2C | Grin2c | +3.78 |

| NM_012784 | Cannabinoid receptor 1 | Cnr1 | +3.76 |

| NM_031853 | Diazepam binding inhibitor | Dbi | +2.37 |

| NM_183327 | GABA-A receptor, subunit gamma 2 | Gabrg2 | +1.92 |

| NM_172036 | GABA-A receptor associated protein | Gabarap | +1.81 |

| NM_012956 | GABA-A receptor, subunit beta 1 | Gabrb1 | +0.99 |

| NM_153308 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA-associated protein 1 (glutamate binding) | Grina | +0.87 |

| XM_579337 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, NMDA 2A | Grin2a | −1.44 |

| NM_017261 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, AMPA 2 | Gria2 | −1.7 |

| XM_579467 | Gephyrin | Gphn | −2.13 |

| NM_017295 | GABA-A receptor, subunit alpha 5 | Gabra5 | −2.71 |

| Genes associated with voltage-gated channels | |||

| NM_021688 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 1 | Kcnk1 | +3.51 |

| NM_172042 | Potassium channel, subfamily K, member 2 | Kcnk2 | +3.32 |

| NM_012856 | Potassium voltage gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 1 | Kcnc1 | +1.66 |

| NM_139216 | Potassium voltage gated channel, Shaw-related subfamily, member 2 | Kcnc2 | +1.62 |

| NM_053351 | Calcium channel, voltage-dependent, gamma subunit 2 | Cacng2 | +1.19 |

| NM_139097 | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type III, beta | Scn3b | −1.14 |

| NM_013186 | Potassium voltage gated channel, Shab-related subfamily, member 1 | Kcnb1 | −1.51 |

| NM_012647 | Sodium channel, voltage-gated, type 2, alpha 1 polypeptide | Scn2a1 | −1.58 |

| NM_024139 | Calcium binding protein p22 | Chp | −1.64 |

| XM_217464 | Calcium binding protein 39 | Cab39 | −1.91 |

| Genes associated with ribosomes and cytoskeleton | |||

| NM_017138 | Laminin receptor 1 (protein SA) | Rpsa | +3.75 |

| NM_022504 | Ribosomal protein L36 | Rpl36 | +3.30 |

| NM_053597 | Ribosomal protein S27 | Rps27 | +2.75 |

| NM_031110 | Ribosomal protein S11 | Rps11 | +2.39 |

| NM_031102 | Ribosomal protein L18 | Rpl18 | +1.95 |

| NM_017150 | Ribosomal protein L29 | Rpl29 | +1.93 |

| NM_022949 | Ribosomal protein L14 | Rpl14 | +1.61 |

| NM_013226 | Ribosomal protein L32 | Rpl32 | +1.41 |

| NM_031065 | Ribosomal protein L10A | Rpl10a | +1.34 |

| NM_017151 | Ribosomal protein S15 | Rps15 | +1.31 |

| XM_575183 | Ribosomal protein L21 | Rpl21 | +1.21 |

| NM_031109 | Ribosomal protein S10 | Rps10 | +1.18 |

| NM_013066 | Microtubule-associated protein 2 | Mtap2 | +1.12 |

| XM_579666 | Tubulin, beta 3 | Tubb3 | −1.08 |

| NM_031783 | Neurofilament, light polypeptide | Nefl | −1.62 |

Gene changes related to neuronal damage and calcium-binding proteins

Only a few genes involved in the apoptotic pathway were changed, i.e. BAD (+1.1 fold), Bcl2-antagonist/killer 1 (+3.31) (involved in cytochrome c release from the mitochondria), calcineurin B (−1.94), and specific components of the cytochrome c oxidase complex (see Tables 1 and 3; and Fig. S1). The most significantly influenced pathway was that for the oxidative phosphorylation (Fig. S1) implicating that the primary responses to the excitoxic damage after KA-induced SE involves oxidative mechanisms.

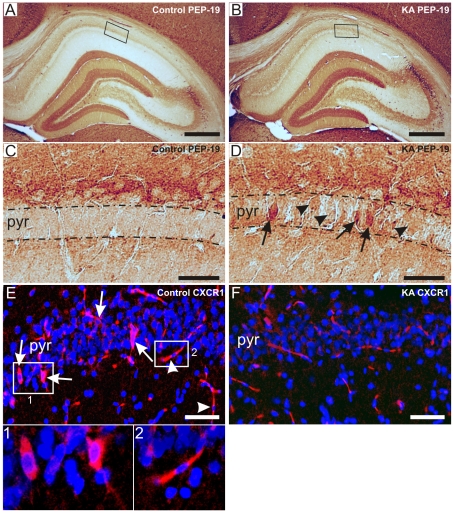

The expression of calmodulin 1 (CaM1) and calmodulin 2 (CaM2) were down-regulated (−1.28 and −1.05, respectively). The expression of two specific CaM kinases, CaMKIIg and CaMKIIb, was up-regulated (+1.61 and +0.66, respectively), and only calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase 1, alpha (CaMKK1) was down-regulated (−1.06). Moreover, the calbindin gene was down-regulated (−5), whereas the expression of several S100 calcium-binding proteins was increased. Among the small neuronal proteins that bind CaM, the PEP-19 gene was the second most up-regulated gene in our study (+13.3), whereas the growth associated protein 43 (GAP-43) gene was down-regulated (−1.89).

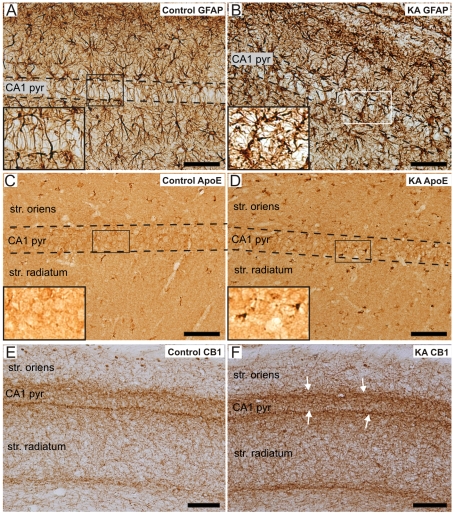

Gene changes associated with gliosis and inflammation

The structural astrocytic protein GFAP was the most dramatically up-regulated gene (+13.7) after SE (Table 3). The expression of the protease inhibitor cystatin C gene was pronouncedly up-regulated (+3.58) together with one of its substrates, cathepsin S (+6.47). Also the annexin A3 (Anxa3) gene, which plays a role in the regulation of cellular growth, showed an increased transcriptome expression (+7.84).

The immunologically-related beta-2 microglobulin (+3.75) and HLA-DMB (+5.84) genes were highly up-regulated, as well as the chemokine receptor CCR5 (+6.51) and the glycoprotein CD74 (+6.1) genes. The interleukin 8 receptor (CXCR1) was highly down-regulated (−6.08), but prostaglandin synthase 2 (PTGS2), also known as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), was up-regulated (+2.48). This inflammatory mediator is also associated to the VEGF signalling pathway, and we found activation of several genes in this pathway after SE (Table 1; Fig. S3). Apo E, another protein expressed in astrocytes, showed an increased expression (+3.76).

Gene changes associated with synaptic transmission

The γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor α5 subunit gene expression was down-regulated (−2.71), whereas the expression of γ2 (+1.92) and β1 (+0.99) subunits were up-regulated (Table 4). We also detected a down-regulation of the gephyrin (−2.13) gene, and an up-regulation of the GABAA receptor-associated protein (GABARAP; +1.81) gene. The gene expression of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit NR2C was up-regulated (+3.78), while the NR2A subunit was down-regulated (−1.44) after SE. Furthermore, the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor subunit GluR2 was down-regulated (−1.7). The concerted action of AMPARs and NMDARs in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in the LTP pathway is shown in Fig. 4. The G protein-coupled receptor CB1 showed an up-regulated expression (+3.76).

Validation of selected genes of interest by immunohistochemistry

The validation of the microarray results was carried out by immunohistochemical detection of the selected genes of interest, i.e. GFAP, apo E, CB1, PEP-19 and CXCR1. Figs. 5A and 5B show representative GFAP immunostainings of the CA1 region in a control and KA-treated rat, respectively. GFAP was heavily increased in astrocytes of the KA-treated rats (see Fig. 5B and the inset). Immunopositive apo E cells appeared in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of KA-treated rats (Fig. 5D) compared to the control rats, in which no positively labelled cells were detected (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, the enhanced apo E immunoreactivity was also detected in the stratum oriens and radiatum of the CA1 region. One of the pronouncedly increased genes after SE in the transcriptome analysis was the CB1 gene, which was specifically enhanced in the borders of the CA1 pyramidal cell layer with both the stratum oriens and radiatum. Figs. 5E and F show the CB1 immunostaining in the CA1 region of a control and KA-treated rat, respectively.

Figure 5. Validation of the microarray results by immunohistochemical staining in control and KA-treated rats.

Immunoreactivity of GFAP in a representative control (A) and KA-treated rat (B). Note the increase in GFAP immunoreactivity and the morphological change in astrocytes of the KA-treated rat (insets in A and B). Figs 5 C and D show the immunoreactivity of apo E in a control and KA-treated rat, respectively. Note the increase in apo E immunostaining in some cells within the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the KA-treated rat compared to the control rat (insets in C and D, respectively). The CB1 immunoreactivity was enhanced more pronouncedly in a KA-treated rat (F) than in a control rat (E) in the borders of the CA1 pyramidal layer with both the stratum oriens and radiatum (white arrows in F). Scale bars: 75 µm in A–D, and 100 µm in E-F. Abbreviations: apo E, apolipoprotein E; CB1, cannabinoid type 1 receptor; CA1 pyr, stratum pyramidale of CA1; GFAP, glial fibrillary protein; KA, kainic acid; str., stratum.

PEP-19 and CXCR1 were among the most up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively. Figs. 6A and 6B show representative PEP-19 immunostainings of the whole hippocampus in a control and KA-treated rat, respectively. With higher magnification, highly enhanced PEP-19 immunoreactivity was observed in some CA1 neurons of KA-treated rats (Fig. 6D, arrows), whereas in the majority of neurons the staining was weak (Fig. 6D, arrowheads). Meanwhile, no PEP-19 immunoreactive neurons could be detected in the CA1 pyramidal layer in control rats (Fig. 6C). Figs. 6E and 6F show representative CXCR1 fluorescent immunostainings of the CA1 region in a control and KA-treated rat, respectively. Positive CXCR1 immunostaining was detected in discrete CA1 neurons of control rats (6E, arrows and insert 1), as well as in vascular endothelial cells as identified by their location and shape (arrowheads and insert 2). In KA-treated rats, no clearly CXCR1 immunoreactive neurons were observed in the CA1 layer (Fig. 6F). The immunostaining results are in line with our corresponding gene expression findings as verified by the microarrays.

Figure 6. Validation of the microarray results by immunohistochemical staining of PEP-19 and CXCR1 in control and KA-treated rats.

Immunoreactivity of PEP-19 in the whole hippocampus in a representative control (A) and KA-treated rat (B). Figs. 6C and Dshow the CA1 region of A and B, respectively, at the higher magnification. Note the lack of PEP-19 immunoreactivity in the CA1 pyramidal layer in the control rat (C), while the staining was weak in the CA1 layer (D, arrowheads), and greatly enhanced in single neurons (D, arrows) in the KA-treated rat. Figs. 6E and Fshow the CXCR1 immunoreactivity in the CA1 region of a control and KA-treated rat. In control rats, immunoreactivity occurred in discrete neurons in the CA1 pyramidal layer (E, arrows and insert 1), and in vascular endothelial cells (E, arrowheads and insert 2). In KA-treated rats, no immunoreactive neurons could be detected (F). Scale bars: 200 µm in A–B, 40 µm in C–D, and 75 µm in E-F. Abbreviations: CXCR1, interleukin 8 receptor; PEP-19, Purkinje cell protein 4; pyr, stratum pyramidale.

Discussion

In this study we elucidated the consequences of KA-induced SE on gene expression in the CA1 pyramidal cell region at the sub-acute phase of epileptogenesis, i.e. one week after SE, in P21 rats, the age roughly comparable to a juvenile child (reviewed in [27]). The CA1 region was microdissected by laser, which gave us an opportunity to focus specifically on this region selectively damaged by SE at this age [7], [23]. It is, so far, incompletely known when the epileptogenic process begins, and which molecular changes are relevant to it. Earlier results, however, suggest that neurodegeneration, that occurs in the hilus and CA1 pyramidal cell layer during the early phase of epileptogenesis, could be one reliable indicator of the epileptogenic process at least in adult rats (reviewed in [28]). A total of 1592 genes were differently expressed in the CA1 sub-region of the KA-treated compared to their age-matched control rats. These genes were involved in several pathways regulating e.g. neuronal damage, Ca2+ homeostasis, glial reactivity, inflammation, and synaptic transmission. The observed alterations in gene expression of the pathways of interest are discussed in the light of earlier studies in adult rats, and their postulated significance in epileptogenesis in juvenile rats.

Differential expression of genes related to neuronal damage and neuroprotection

The mechanism of SE-induced CA1 pyramidal cell damage and the role of calcium

In our model, the CA1 neurons were selectively damaged in the P21 rats one week after SE. However, our results suggest that the activation of the apoptotic pathway may not be involved in the damage process. In adult rats both apoptotic and necrotic mechanisms contribute to neuronal degeneration in all hippocampal subregions after KA-induced SE [29], [30], followed by progressive neuronal loss, detectable within one week after SE [5], [31], [32]. SE-induced up-regulation of genes associated with apoptosis, such as caspase-3, p53, and BAX, have also been detected in adult rats [13], [33], [34], [35]. At variance in the P21 rats, the expression of these genes did not significantly differ from those of the control rats, although the positive FJB-staining of CA1 neurons persisted at least for one week. The contribution of non-apoptotic mechanisms in the CA1 region after SE is also corroborated by our recent finding that the expression of Bax and caspase-3 proteins remained unchanged after SE in P21 rats [23].

The S100 proteins are a family of calcium-binding, EF-hand proteins localized to astrocytes. They are involved in Ca2+ regulation in a variety of intracellular pathways [36]. The up-regulation of the S100B protein has been found in previous studies [37], [38] suggesting an activation of pathways, which lead to increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations in astrocytes [36]. The calbindin gene, abundantly expressed in dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells, and to some extent also in CA1 pyramidal neurons [22], [39], was now down-regulated. This is in accordance with earlier studies in adult rats, in which the calbindin gene has been down-regulated in the hippocampal subregions 1–4 weeks after pilocarpine-induced SE [40], [41], and its immunoreactivity attenuated in CA1 pyramidal neurons one week after KA- or electrically-induced SE [42], [43], suggesting for an attenuated regulation of intracellular Ca2+ levels upon stimulation [39], [41]. Another highly up-regulated transcript in our study was that of PEP-19, a small neuronal protein involved in the calcium-binding to CaM [44]. PEP-19 is highly expressed in hippocampal CA2 pyramidal cells, which display resistance to epileptic damage possibly due to their higher Ca2+ buffering capacity [45]. Furthermore, PEP-19 has shown neuroprotective properties in cell cultures, these possibly being mediated through CaM inhibition that could lead to enhanced resistance of neurons to calcium-mediated toxicity [46], [47], which makes it tempting to speculate that this protein is neuroprotective also in our SE model. The reduced CaM expression in our study is also interesting since there is extensive evidence that CaM plays a critical role in the induction of cell death following Ca2+ overload, and inhibition of CaM function can protect neurons from death [48], [49]. Overall, our present results suggest that genes in the pathways regulating the cellular Ca2+ homeostasis are one of the major targets modified by SE in juvenile rats. Also recent studies in adult rats suggest that those neurons that survive after seizures exhibit prolonged alterations in neuronal Ca2+ dynamics that could play an important role in the induction and maintenance of prolonged plastic changes characteristic for the epileptic phenotype [41], [50].

Genes associated with gliosis and inflammation

The structural astrocytic protein GFAP was the most dramatically up-regulated gene after SE in keeping with earlier studies in adult experimental epilepsy models, i.e. one day after KA-induced SE [14], 14 days after pilocarpine-induced SE [21], and 8 days after electrically-induced SE [51]. In line with the gene expression results, enhanced GFAP protein expression has been detected within days after SE in the hippocampus of various experimental epilepsy models in the immature (P15–P21) [7], [52], and adult rats [38], [53], [54]. Also the morphology of astrocytes is altered by SE, fibrous astrocytes with long processes being replaced by reactive astrocytes with thickened, heavily GFAP-postitive processes [7], [37]. Comparable changes were also detected in our study corroborating the significant role of glial cells at the early phase of epileptogenesis. The increased GFAP expression is consistent with earlier studies of glial cell activation known to accompany different types of neural injury [55], [56].

The expression of the protease inhibitor cystatin C gene was likewise pronouncedly up-regulated in keeping with earlier studies, in which it has been up-regulated in reactive astrocytes, activated microglia, and in CA1 pyramidal neurons after electrically-induced SE in adult rats [43], [51]. Functionally, cystatin C may protect cells as it inhibits the proteolytic effect of cathepsins [57], [58]. Interestingly, also the gene expression of the lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin S has been up-regulated in the hippocampus after SE in adult rats [17], as well as in microglial cells surrounding the degenerating CA1 pyramidal neurons in juvenile mice [59]. Although the members of the cathepsin family may contribute to neuronal apoptosis when secreted by activated microglia [60], [61], the significance of cathepsin S gene up-regulation observed now remains speculative, since our other data suggest that apoptosis seems not to be activated by SE in P21 rats.

Several genes mediating inflammatory processes were also highly up-regulated, such as the chemokine receptor CCR5, and the glycoprotein CD74. This is in line with earlier studies which have shown that seizures induce the expression of different chemokines and cytokines in adult and immature brain [7], [16], [52]. CCR5 is expressed in both neuronal and glial cells in the rat brain. Moreover, its expression is time-dependently enhanced in the adult rat hippocampus after KA-induced seizures concomitant to neurodegeneration [62]. It has been proposed that the CCR5-expressing glial cells could play a distinct pathophysiological role in contributing to the progression of injury and/or be a part of intrinsic repair mechanisms [62]. The CXCR1 gene, expressed both in hippocampal neurons and astrocytes [63], as well as in endothelial cells [64], [65], was now down-regulated. CXCR1 is a G-protein-coupled receptor activated by the pro-inflammatory chemokine, interleukin-8 (IL-8 or CXCL8), that is up-regulated under acute inflammatory conditions, e.g. after ischemia in the adult rabbit brain [66]. IL-8 may reduce Ca2+ currents through CXCR1, which may modify neuronal excitability [67]. Indeed, a neutralizing anti-IL-8 antibody has significantly reduced ischemia-induced brain damage [66], further suggesting that inhibition of IL-8 binding to its receptor CXCR1 is another potential target for inhibiting the IL-8 effects [68], and the decreased CXCR1 expression may play a neuroprotective role. Moreover, activation of the COX-2 gene occurred in our model in accordance with earlier transcriptome studies in adult rats [13], [16], [69], and its enhanced immunoreactivity has recently been detected in several hippocampal subregions, including the CA1 region after SE [23]. This inflammatory mediator is also associated to the VEGF signalling pathway supporting the idea of recent studies that seizures promote angiogenesis [13], [70], which could contribute to the recovery process after SE.

Apo E is postulated to modulate the astroglial response to damage, and to play a role in neuronal repair and re-innervation of the damaged circuitry [71]. This molecule is the major constituent of brain lipoproteins abundantly expressed in astrocytes [72]. It was now highly up-regulated in accordance with earlier studies in the adult rat hippocampus after systemic KA- and electrically-induced SE [51], [73]. Taken together, our current transcriptome results together with the earlier studies by other groups strongly favour the idea that activated microglia and astrocytes play a pivotal role in immune responses as well as in the damage and repair processes of the CA1 pyramidal neurons in juvenile P21 rats after SE.

Genes associated with neurotransmission and signal transduction

GABAA, NMDA and cannabinoid receptor signalling

There is extensive evidence that seizures trigger alterations in the GABAergic inhibition as well as in the GABAA receptor subunit expression in the adult [74], [75], [76] and immature (P9) rat brain [77]. Corroborating our findings, the observed down-regulation of the α5 subunit and up-regulation of the γ2 subunit along with a decreased δ and increased α4 subunit expression, have been found in several adult experimental TLE models [16], [69], [74], [78], [79]. Interestingly, changes in these subunits could alter both tonic and phasic inhibition, as the δ, α4 and α5 subunits are primarily found in extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, which mediate tonic inhibitory currents [80], [81], [82], whereas the γ2 subunit is mainly localized to synaptic receptors that play a major role in phasic inhibition [83], [84]. A decreased α5 subunit expression has, however, resulted in enhanced tonic inhibition in CA1 pyramidal cells in adult rats after pilocarpine-induced seizures [85] supporting the idea that compensatory up-regulation of other extrasynaptic GABAA receptors, possibly those containing α4 subunit, may take place. Thus, when the α5 or δ subunit expression is decreased, the γ2 subunit is translocated from synaptic to perisynaptic sites and increases its partnership with the α4 subunit in the epileptic brain [78].

We also detected a down-regulation of the gephyrin gene and an up-regulation of the GABARAP gene in accordance with the results obtained from the hippocampi of humans with TLE [86]. Gephyrin and GABARAP are essential proteins in the postsynaptic clustering of γ2 subunit-containing GABAA receptors [87], [88], and the gephyrin down-regulation could further corroborate the hypothesis that the γ2 subunit translocates from synaptic to perisynaptic sites during epileptogenesis.

In hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells, activation of NMDA receptors and subsequent Ca2+ influx is connected to the induction of synaptic plasticity through LTP [89]. The low NR2A and high NR2C transcriptome expression detected now implicates a recapitulation of an immature NMDA receptor phenotype after SE, as the NR2B and NR2C subunits are highly expressed in the developing hippocampus, and around the third postnatal weeks these two subunits are replaced by NR2A and NR2D [90]. Changes in NMDA receptor subunits have been proposed to cause deficits in long-term spatial learning ability [91]. Furthermore, the increased NR2C subunit expression in our model may also be associated with the induction of CaM kinase II isoforms, which are involved in the NMDA receptor-mediated Ca2+ signalling in an in vitro model of epilepsy [92].

Decreased expression of the AMPA receptor GluR2 subunit gene has earlier been detected in the CA3 region shortly after KA-induced and electrically-induced SE in adult rats, in keeping with our present finding [16], [93]. During the first two postnatal weeks in rats, the expression of the GluR2 subunit-containing AMPARs are increased in the CA1 region [90], leading to attenuated Ca2+ influx, since this subunit exhibits low permeability to Ca2+ [94]. The reduced expression of the GluR2 subunit in the juvenile rats after SE could therefore lead to Ca2+ overload in CA1 pyramidal neurons, and contribute to their damage.

The G-protein-coupled CB1s are mainly found on the nerve terminals of cholecystokinin-containing GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus [95]. Exogenous cannabinoids act on presynaptic CB1s and block voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and reduce Ca2+ influx necessary for GABA release [95], [96]. This can result in decreased GABA-mediated inhibitory currents [97] that could facilitate LTP induction [98]. The up-regulated CB1 receptor gene expression in our study is in line with earlier studies, in which CB1 receptors were up-regulated after seizures in adult rats [99], [100]. This suggests that the cannabinoid system is one regulator of seizure activity. Moreover, KA-induced seizures increase endocannabinoid levels in the normal mice hippocampus, and induce more severe neuronal damage in the hippocampus of CB1 knockout mice [101]. It is thus possible that also in our juvenile rats SE-induced CB1 activation may trigger endocannabinoid release that could serve as a neuroprotective factor.

Concluding remarks

The transcriptome analysis of the hippocampal CA1 subregion one week after SE in P21 rats with respect to their age-matched control rats resulted in differentially expressed genes associated to several pathways. Induced expression of several genes related to the Ca2+ signalling pathway, and the glial and inflammatory responses were observed, but only a few genes that were related to the apoptotic pathway. The observed absence of apoptosis may be associated with the developmental stage of the CA1 pyramidal neurons in P21 rats and/or a possible beneficial role of astrocytic cells in the repair processes of pyramidal neurons. The vast majority of the CA1 pyramidal neurons, although damaged (as indicated by positive FJB-staining), survived at least for one week after SE, but the altered gene expression suggest on-going epileptogenic processes in this sub-region. The alterations in the expression of several GABAA receptor subunits and that of CB1 may, on the other hand, be of importance for seizure regulation. Moreover, several molecular mechanisms occurring during epileptogenesis in our juvenile rats are similar to those in adult rats. However, the highly up-regulated expression of the calcium-binding protein PEP-19 gene, and the down-regulation of the CXCR1 gene, involved in inflammation, seem to be specific for this age. Further studies are needed to reveal whether these molecules have a possible role in neuroprotection, and whether they can provide new leads to better understand the mechanisms of epileptogenesis in the juvenile hippocampus.

Supporting Information

The KEGG-derived oxidative phosphorylation pathway. Oxidative phosphorylation was the most significantly influenced pathway in our transcriptome analysis. Specific components of the cytochrome c oxidase complex were also activated, and these genes are encircled in the figure. The table below shows the entire list of the up- or down-regulated genes on the microarray related to this pathway.

(0.99 MB TIF)

The KEGG-derived ribosomal pathway. The figure shows gene changes found in the various components of the ribosomal machinery, with the genes altered on the microarray encircled. An increased expression of many genes encoding ribosomal proteins was found after SE as shown in the table. This could indicate that the cells actively change their protein synthesis capacity after seizures.

(0.59 MB TIF)

The KEGG-derived VEGF signaling pathway. The VEGF signalling pathway with the genes activated on the microarray encircled. In this pathway, 13 genes were changed, of which 9 were down-regulated as seen in the table.

(0.38 MB TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Jouko Sandholm (MSc) for assistance with the microdissection.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The financial support of the Academy of Finland, projects # 8117438 (IEH) and # 8127008 (HBL), the Arvo and Lea Ylppo Foundation (IEH), the Finnish Cultural Foundation (HBL), the Drug Discovery Graduate School (HBL), and the Finnish Graduate School of Neuroscience (FRL) are gratefully acknowledged. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Pitkänen A, Sutula TP. Is epilepsy a progressive disorder? Prospects for new therapeutic approaches in temporal-lobe epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sander JW. The epidemiology of epilepsy revisited. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:165–170. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063766.15877.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperk G, Lassmann H, Baran H, Kish SJ, Seitelberger F, et al. Kainic acid induced seizures: neurochemical and histopathological changes. Neuroscience. 1983;10:1301–1315. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Ari Y. Limbic seizure and brain damage produced by kainic acid: mechanisms and relevance to human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1985;14:375–403. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Covolan L, Mello LE. Temporal profile of neuronal injury following pilocarpine or kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2000;39:133–152. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00119-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas KZ, Sperber EF, Opanashuk LA, Stanton PK, Moshe SL. Resistance of immature hippocampus to morphologic and physiologic alterations following status epilepticus or kindling. Hippocampus. 2001;11:615–625. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzi M, Perego C, Aliprandi M, Richichi C, Ravizza T, et al. Glia activation and cytokine increase in rat hippocampus by kainic acid-induced status epilepticus during postnatal development. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopez-Picon F, Puustinen N, Kukko-Lukjanov TK, Holopainen IE. Resistance of neurofilaments to degradation, and lack of neuronal death and mossy fiber sprouting after kainic acid-induced status epilepticus in the developing rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadler JV, Perry BW, Cotman CW. Intraventricular kainic acid preferentially destroys hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 1978;271:676–677. doi: 10.1038/271676a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wasterlain CG, Niquet J, Thompson KW, Baldwin R, Liu H, et al. Seizure-induced neuronal death in the immature brain. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:335–353. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams PA, White AM, Clark S, Ferraro DJ, Swiercz W, et al. Development of spontaneous recurrent seizures after kainate-induced status epilepticus. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2103–2112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0980-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperber EF, Haas KZ, Stanton PK, Moshe SL. Resistance of the immature hippocampus to seizure-induced synaptic reorganization. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1991;60:88–93. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90158-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunsberger JG, Bennett AH, Selvanayagam E, Duman RS, Newton SS. Gene profiling the response to kainic acid induced seizures. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;141:95–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Y, Lu A, Aronow BJ, Wagner KR, Sharp FR. Genomic responses of the brain to ischemic stroke, intracerebral haemorrhage, kainate seizures, hypoglycemia, and hypoxia. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1937–1952. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandberg R, Yasuda R, Pankratz DG, Carter TA, Del Rio JA, et al. Regional and strain-specific gene expression mapping in the adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11038–11043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Breit T, Rauwerda H, et al. Potential new antiepileptogenic targets indicated by microarray analysis in a rat model for temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11083–11110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2766-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukasiuk K, Kontula L, Pitkänen A. cDNA profiling of epileptogenesis in the rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:271–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.French PJ, O'Connor V, Voss K, Stean T, Hunt SP, et al. Seizure-induced gene expression in area CA1 of the mouse hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:2037–2041. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Lein ES, He A, Smith SC, Aston C, et al. Transcriptional profiling reveals strict boundaries between hippocampal subregions. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:187–196. doi: 10.1002/cne.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker AJ, Chen J, Zien A, Sochivko D, Normann S, et al. Correlated stage- and subfield-associated hippocampal gene expression patterns in experimental and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:2792–2802. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2003.02993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott RC, Miles MF, Lowenstein DH. Overlapping microarray profiles of dentate gyrus gene expression during development- and epilepsy-associated neurogenesis and axon outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2218–2227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02218.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lein ES, Zhao X, Gage FH. Defining a molecular atlas of the hippocampus using DNA microarrays and high-throughput in situ hybridization. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3879–3889. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4710-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Järvelä JT, Lopez-Picon FR, Holopainen IE. Age-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 induction and neuronal damage after status epilepticus in the postnatal rat hippocampus. Epilepsia. 2008;49:832–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tavazoie S, Hughes JD, Campbell MJ, Cho RJ, Church GM. Systematic determination of genetic network architecture. Nat Genet. 1999;22:281–285. doi: 10.1038/10343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Picon FR, Uusi-Oukari M, Holopainen IE. Differential expression and localization of the phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated neurofilaments during the early postnatal development of rat hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2003;13:767–779. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ. Fluoro-Jade B: a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 2000;874:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haut SR, Veliskova J, Moshe SL. Susceptibility of immature and adult brains to seizure effects. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:608–617. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00881-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitkänen A, Lukasiuk K. Molecular and cellular basis of epileptogenesis in symptomatic epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14(Suppl 1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bengzon J, Kokaia Z, Elmer E, Nanobashvili A, Kokaia M, et al. Apoptosis and proliferation of dentate gyrus neurons after single and intermittent limbic seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10432–10437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujikawa DG, Shinmei SS, Cai B. Kainic acid-induced seizures produce necrotic, not apoptotic, neurons with internucleosomal DNA cleavage: implications for programmed cell death mechanisms. Neuroscience. 2000;98:41–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorter JA, Goncalves Pereira PM, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Lopes da Silva FH, et al. Neuronal cell death in a rat model for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy is induced by the initial status epilepticus and not by later repeated spontaneous seizures. Epilepsia. 2003;44:647–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.53902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao MS, Hattiangady B, Reddy DS, Shetty AK. Hippocampal neurodegeneration, spontaneous seizures, and mossy fiber sprouting in the F344 rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1088–1105. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakhi S, Bruce A, Sun N, Tocco G, Baudry M, et al. p53 induction is associated with neuronal damage in the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7525–7529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillardon F, Wickert H, Zimmermann M. Up-regulation of bax and down-regulation of bcl-2 is associated with kainate-induced apoptosis in mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 1995;192:85–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11619-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henshall DC, Chen J, Simon RP. Involvement of caspase-3-like protease in the mechanism of cell death following focally evoked limbic seizures. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1215–1223. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barger SW, Van Eldik LJ. S100 beta stimulates calcium fluxes in glial and neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:9689–9694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shapiro LA, Wang L, Ribak CE. Rapid astrocyte and microglial activation following pilocarpine-induced seizures in rats. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 2):33–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bendotti C, Guglielmetti F, Tortarolo M, Samanin R, Hirst WD. Differential expression of S100beta and glial fibrillary acidic protein in the hippocampus after kainic acid-induced lesions and mossy fiber sprouting in adult rat. Exp Neurol. 2000;161:317–329. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sloviter RS. Calcium-binding protein (calbindin-D28k) and parvalbumin immunocytochemistry: localization in the rat hippocampus with specific reference to the selective vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to seizure activity. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:183–196. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang FR, Chia SC, Jiang FL, Ma DL, Chen PM, et al. Calcium binding protein containing neurons in the gliotic mouse hippocampus with special reference to their afferents from the medial septum and the entorhinal cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;140:1467–1479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter DS, Harrison AJ, Falenski KW, Blair RE, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-term decrease in calbindin-D28K expression in the hippocampus of epileptic rats following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2008;79:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouilleret V, Loup F, Kiener T, Marescaux C, Fritschy JM. Early loss of interneurons and delayed subunit-specific changes in GABA(A)-receptor expression in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2000;10:305–324. doi: 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:3<305::AID-HIPO11>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aronica E, van Vliet EA, Hendriksen E, Troost D, Lopes da Silva FH, et al. Cystatin C, a cysteine protease inhibitor, is persistently up-regulated in neurons and glia in a rat model for mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1485–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slemmon JR, Morgan JI, Fullerton SM, Danho W, Hilbush BS, et al. Camstatins are peptide antagonists of calmodulin based upon a conserved structural motif in PEP-19, neurogranin, and neuromodulin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15911–15917. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.15911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leranth C, Ribak CE. Calcium-binding proteins are concentrated in the CA2 field of the monkey hippocampus: a possible key to this region's resistance to epileptic damage. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85:129–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00229993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erhardt JA, Legos JJ, Johanson RA, Slemmon JR, Wang X. Expression of PEP-19 inhibits apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3719–3723. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011270-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kanazawa Y, Makino M, Morishima Y, Yamada K, Nabeshima T, et al. Degradation of PEP-19, a calmodulin-binding protein, by calpain is implicated in neuronal cell death induced by intracellular Ca2+ overload. Neuroscience. 2008;154:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hashiguchi A, Kawano T, Yano S, Morioka M, Hamada J, et al. The neuroprotective effect of a novel calmodulin antagonist, 3-[2-[4-(3-chloro-2-methylphenyl)-1-piperazinyl]ethyl]-5,6-dimethoxy-1-(4-imidazo lylmethyl)-1H-indazole dihydrochloride 3.5 hydrate, in transient forebrain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2003;121:379–386. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takano H, Sugimura M, Kanazawa Y, Uchida T, Morishima Y, et al. Protective effect of DY-9760e, a calmodulin antagonist, against neuronal cell death. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:1788–1791. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:229–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendriksen H, Datson NA, Ghijsen WE, van Vliet EA, da Silva FH, et al. Altered hippocampal gene expression prior to the onset of spontaneous seizures in the rat post-status epilepticus model. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1475–1484. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ravizza T, Rizzi M, Perego C, Richichi C, Veliskova J, et al. Inflammatory response and glia activation in developing rat hippocampus after status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 5):113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.01006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torre ER, Lothman E, Steward O. Glial response to neuronal activity: GFAP-mRNA and protein levels are transiently increased in the hippocampus after seizures. Brain Res. 1993;631:256–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding M, Haglid KG, Hamberger A. Quantitative immunochemistry on neuronal loss, reactive gliosis and BBB damage in cortex/striatum and hippocampus/amygdala after systemic kainic acid administration. Neurochem Int. 2000;36:313–318. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benkovic SA, O'Callaghan JP, Miller DB. Sensitive indicators of injury reveal hippocampal damage in C57BL/6J mice treated with kainic acid in the absence of tonic-clonic seizures. Brain Res. 2004;1024:59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eng LF, Ghirnikar RS, Lee YL. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: GFAP-thirty-one years (1969–2000). Neurochem Res. 2000;25:1439–1451. doi: 10.1023/a:1007677003387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brzin J, Popovic T, Turk V, Borchart U, Machleidt W. Human cystatin, a new protein inhibitor of cysteine proteinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;118:103–109. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marks N, Stern F, Chi LM, Berg MJ. Diversity of rat brain cysteine proteinase inhibitors: isolation of low-molecular-weight cystatins and a higher-molecular weight T-kininogen-like glycoprotein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;267:448–458. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akahoshi N, Murashima YL, Himi T, Ishizaki Y, Ishii I. Increased expression of the lysosomal protease cathepsin S in hippocampal microglia following kainate-induced seizures. Neurosci Lett. 2007;429:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kingham PJ, Pocock JM. Microglial secreted cathepsin B induces neuronal apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1475–1484. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamashima T. Implication of cysteine proteases calpain, cathepsin and caspase in ischemic neuronal death of primates. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:273–295. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mennicken F, Chabot JG, Quirion R. Systemic administration of kainic acid in adult rat stimulates expression of the chemokine receptor CCR5 in the forebrain. Glia. 2002;37:124–138. doi: 10.1002/glia.10021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Danik M, Puma C, Quirion R, Williams S. Widely expressed transcripts for chemokine receptor CXCR1 in identified glutamatergic, gamma-aminobutyric acidergic, and cholinergic neurons and astrocytes of the rat brain: a single-cell reverse transcription-multiplex polymerase chain reaction study. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:286–295. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murdoch C, Monk PN, Finn A. Cxc chemokine receptor expression on human endothelial cells. Cytokine. 1999;11:704–712. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsumoto T, Ikeda K, Mukaida N, Harada A, Matsumoto Y, et al. Prevention of cerebral edema and infarct in cerebral reperfusion injury by an antibody to interleukin-8. Lab Invest. 1997;77:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puma C, Danik M, Quirion R, Ramon F, Williams S. The chemokine interleukin-8 acutely reduces Ca(2+) currents in identified cholinergic septal neurons expressing CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptor mRNAs. J Neurochem. 2001;78:960–971. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahuja SK, Lee JC, Murphy PM. CXC chemokines bind to unique sets of selectivity determinants that can function independently and are broadly distributed on multiple domains of human interleukin-8 receptor B. Determinants of high affinity binding and receptor activation are distinct. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:225–232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matzilevich DA, Rall JM, Moore AN, Grill RJ, Dash PK. High-density microarray analysis of hippocampal gene expression following experimental brain injury. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:646–663. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hellsten J, West MJ, Arvidsson A, Ekstrand J, Jansson L, et al. Electroconvulsive seizures induce angiogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:871–878. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Champagne D, Rochford J, Poirier J. Effect of apolipoprotein E deficiency on reactive sprouting in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus following entorhinal cortex lesion: role of the astroglial response. Exp Neurol. 2005;194:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boyles JK, Pitas RE, Wilson E, Mahley RW, Taylor JM. Apolipoprotein E associated with astrocytic glia of the central nervous system and with nonmyelinating glia of the peripheral nervous system. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1501–1513. doi: 10.1172/JCI112130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Montpied P, de Bock F, Lerner-Natoli M, Bockaert J, Rondouin G. Hippocampal alterations of apolipoprotein E and D mRNA levels in vivo and in vitro following kainate excitotoxicity. Epilepsy Res. 1999;35:135–146. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(99)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rice A, Rafiq A, Shapiro SM, Jakoi ER, Coulter DA, et al. Long-lasting reduction of inhibitory function and gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor subunit mRNA expression in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9665–9669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA. Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med. 1998;4:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fritschy JM, Kiener T, Bouilleret V, Loup F. GABAergic neurons and GABA(A)-receptors in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurochem Int. 1999;34:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Laurén HB, Lopez-Picon FR, Korpi ER, Holopainen IE. Kainic acid-induced status epilepticus alters GABA(A) receptor subunit mRNA and protein expression in the developing rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1384–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang N, Wei W, Mody I, Houser CR. Altered localization of GABA(A) receptor subunits on dentate granule cell dendrites influences tonic and phasic inhibition in a mouse model of epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2007;27:7520–7531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1555-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Houser CR, Esclapez M. Downregulation of the alpha5 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor in the pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2003;13:633–645. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brunig I, Scotti E, Sidler C, Fritschy JM. Intact sorting, targeting, and clustering of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor subtypes in hippocampal neurons in vitro. J Comp Neurol. 2002;443:43–55. doi: 10.1002/cne.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caraiscos VB, Elliott EM, You-Ten KE, Cheng VY, Belelli D, et al. Tonic inhibition in mouse hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by alpha5 subunit-containing gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3662–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307231101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mody I. Distinguishing between GABA(A) receptors responsible for tonic and phasic conductances. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:907–913. doi: 10.1023/a:1012376215967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Somogyi P, Fritschy JM, Benke D, Roberts JD, Sieghart W. The gamma 2 subunit of the GABAA receptor is concentrated in synaptic junctions containing the alpha 1 and beta 2/3 subunits in hippocampus, cerebellum and globus pallidus. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:1425–1444. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(96)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nusser Z, Mody I. Selective modulation of tonic and phasic inhibitions in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2624–2628. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.5.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scimemi A, Semyanov A, Sperk G, Kullmann DM, Walker MC. Multiple and plastic receptors mediate tonic GABAA receptor currents in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10016–10024. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2520-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Özbas-Gerceker F, Redeker S, Boer K, Özguc M, Saygi S, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression in the hippocampus of patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2006;138:457–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Essrich C, Lorez M, Benson JA, Fritschy JM, Luscher B. Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the gamma 2 subunit and gephyrin. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:563–571. doi: 10.1038/2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang H, Bedford FK, Brandon NJ, Moss SJ, Olsen RW. GABA(A)-receptor-associated protein links GABA(A) receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 1999;397:69–72. doi: 10.1038/16264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.MacDonald JF, Jackson MF, Beazely MA. Hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity and signal amplification of NMDA receptors. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2006;18:71–84. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v18.i1-2.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ritter LM, Vazquez DM, Meador-Woodruff JH. Ontogeny of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit expression in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bo T, Jiang Y, Cao H, Wang J, Wu X. Long-term effects of seizures in neonatal rats on spatial learning ability and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor expression in the brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]