Abstract

Many neurogenetic disorders are caused by unstable expansions of tandem repeats. Some of the causal mutations are located in non-protein-coding regions of genes. When pathologically expanded, these repeats can trigger focal epigenetic changes that repress the expression of the mutant allele. When the mutant gene is not repressed, the transcripts containing the expanded repeat can give rise to a toxic gain-of-function by the mutant RNA. These two mechanisms, heterochromatin-mediated gene repression and RNA dominance, produce a wide range of neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative abnormalities. Here we review the mechanisms of gene dysregulation induced by non-coding repeat expansions, and early indications that some of these disorders may prove to be responsive to therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: myotonic dystrophy, RNA dominance, epigenetics, Friedreich ataxia, fragile X syndrome, MBNL, trinucleotide repeat

More than 20 human neuropsychiatric diseases are caused by genomic expansions of simple tandem repeats [reviewed by (Gatchel and Zoghbi, 2005)]. When these mutations were initially discovered it quickly became apparent that they exhibit an unprecedented degree of genetic instability [reviewed by (Pearson et al., 2005)]. For example, the size of the repeat is likely to change when transmitted from one generation to the next. In fact, intergenerational increments of hundreds of repeats are routinely seen in some of these disorders. These mutations are also unstable in somatic cells, leading to age-dependent growth of the expansion during the life of an individual. The net effect is to create large tandem arrays of simple repeats, a type of genomic element that previously has been associated with focal epigenetic changes (Martens et al., 2005).

The unstable repeat expansion disorders fall in two broad categories according to the position of the repeat element within the mutant gene. In most cases the repeat tract is located in protein coding sequences. For these conditions the repeat is invariably a triplet, the motif is CAG, and the orientation in the reading frame specifies a run of glutamine codons. [Polyglutamine disorders are discussed in recent reviews by (Shao and Diamond, 2007; Orr and Zoghbi, 2007; Williams and Paulson, 2008; Bauer and Nukina, 2009)]. In the normal population the CAG repeats at these loci are polymorphic, and differences in the number of consecutive glutamines may subtly modulate function of the encoded protein. When the repeat length exceeds a threshold, usually of around 40 units, neurodegeneration will result, with the age of onset determined, at least in part, by the extent of the pathological expansion. While these expanded polyglutamine proteins generally are widely expressed, the associated phenotypes are mainly neurodegenerative.

The second major group of unstable repeat expansions disorders are caused by repeats in non-protein-coding regions of genes. For these disorders the genetic features and mechanisms are more diverse. The non-coding expansions typically cause multisystem disease and the phenotypes can be developmental, degenerative, or both. The purpose of this review is to summarize evidence that epigenetic mechanisms are fundamentally involved in pathogenesis of non-coding repeat expansion disorders, and to consider how these mechanisms may create opportunities for novel therapy.

Expanded repeats in non-coding regions

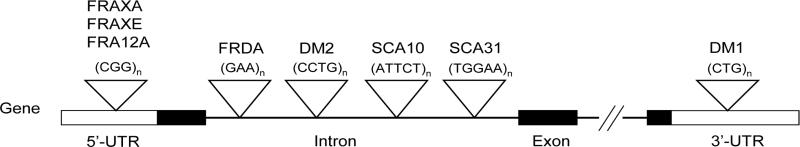

The non-coding repeat expansions involve various sequence motifs in different intragenic positions (Fig. 1, Table 1). For example, the expansion is a CGG repeat in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of FMR1 in fragile X syndrome (FXS) (Verkerk et al., 1991), a GAA repeat in the first intron of Frataxin in Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) (Campuzano et al., 1996), and a CTG repeat in the 3′ UTR of DMPK in myotonic dystrophy type 1 (Brook et al., 1992) (Figure 1). The resulting phenotypes also are quite diverse (Table 1). FXS is the most common cause of hereditary mental retardation (Garber et al., 2008). Friedreich's ataxia is the most common cause of hereditary ataxia in Indo-European populations, and is often accompanied by cardiomyopathy (Pandolfo, 2008). Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is the most common cause of muscular dystrophy in adults, and is characterized by CNS involvement (hypersomnolence and cognitive dysfunction), cataracts, and cardiac dysrhythmias (Harper, 2001).

Figure 1. Location of unstable non-coding repeats within their respective genes.

The sequences and locations of non-coding expanded repeats are shown. The figure does not include expanded tandem repeats in which there is uncertainty whether the primary pathogenic effect is related to expression of a coding or non-coding repeat, such as, spinocerebellar ataxia type 8 or Huntington's disease-like 2.

Table 1.

Unstable non-coding repeats and associated diseases. Note that this table does not include disorders in which repeats may lie in coding or non-coding sequence, depends on which strand is transcribed (Huntington disease-like 2 or spinocerebellar ataxia type 8). AR, autosomal recessive; XL, X-linked; AD, autosomal dominant; FRAXE, fragile X syndrome E; FXTAS, fragile X tremor and ataxia syndrome; SCA10, spinocerebellar ataxia type 10.

| Disease | Inheritance | Gene | Location | Repeat motif | Normal repeat size | Expanded repeat size | Symptoms | Epigenetic effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedreich ataxia | AR | FXN | Intron 1 | (GAA)n | 6-32 | >200 | Ataxia, cardiomyopathy, diabetes | CpG methylation, histone modification, transcriptional silencing |

| Fragile X syndrome A (FRAXA) | XL | FMR1 | 5'-UTR | (CGG)n | 6-52 | >200 | Mental retardation | CpG methylation, histone modification, transcriptional silencing, bi-directional transcription |

| FRAXE | XL | FMR2, FMR3 | 5'-UTR | (CGG)n | 4-39 | 200-900 | Mental retardation | CpG methylation |

| FXTAS | XL | FMR1 | 5'-UTR | (CGG)n | 6-52 | 55-200 | Tremor, ataxia, cognitive dysfunction | CpG methylation, bi-directional transcription |

| Myotonic dystrophy type 1 | AD | DMPK | 3'-UTR | (CTG)n | 5-37 | >50 | Muscle weakness, myotonia, cardiac conduction deficit, cognitive dysfunction | RNA dominance, CpG methylation, histone modification, bi-directional transcription |

| Myotonic dystrophy type 2 | AD | ZNF9 | Intron 1 | (CCTG)n | 10-26 | >75 | Muscle weakness, myotonia, cardiac conduction deficit | RNA dominance |

| SCA10 | AD | ATXN10 | Intron 9 | (AATCT)n | 10-29 | 800-4500 | Ataxia, seizure | Unknown |

Similar to the polyglutamine diseases, the size of a non-coding expanded repeat may correlate with disease severity, as observed in DM1 and FRDA (Hunter et al., 1992; Filla et al., 1996). However, expansion length can also modulate phenotype in a qualitative, discontinuous fashion. For example, the multisystem degenerative features of classical DM1 are usually associated with several hundred CTG repeats in the 3′ UTR of DMPK, as determined by genetic analysis of peripheral blood. When the expansion exceeds a threshold of around 1000 repeats, however, it often impacts fetal development, leading to impaired muscle differentiation and mental retardation (congenital DM1) (Tsilfidis et al., 1992). A similar shift between developmental and degenerative features occurs in FXS (Hagerman and Hagerman, 2004). The CNS dysfunction and maldevelopment in FXS result from expansions of 200 or more CGG repeats in the 5′ UTR of FMR1. In contrast, individuals with smaller expansions, in the range of 55 to 200 CGG repeats, are at risk for a late-onset neurodegenerative syndrome of ataxia, tremor, and cognitive impairment (fraxile X tremor ataxia syndrome, or FXTAS).

The wide spectrum of phenotypes in non-coding repeat expansion disorders reflects the diversity of underlying molecular mechanisms. Two broad categories of biologic effects have emerged: (1) gene silencing, which can affect the gene containing the repeat or flanking genes; and (2) RNA dominance, which entails a deleterious gain-of-function by transcripts that contain an expanded repeat. Furthermore, the epigenetic changes that are triggered by expanded repeats can, in turn, modulate the genetic stability of the repeat tract. We will consider these mechanisms in the context of the three commonest non-coding repeat expansion disorders, FXS, FRDA, and myotonic dystrophy.

Gene silencing

The critical effect of the expanded repeat in fragile X syndrome (FXS) is to induce transcriptional silencing of FMR1, a gene encoding an mRNA binding protein. FMR1 protein regulates translation at the synapse, and its loss is believed to compromise synapse formation and neuronal plasticity (Darnell et al., 2001; Huber et al., 2002). The location of the CGG repeat in the 5′ UTR is close to the FMR1 promoter (~ 100 bp). Expansions of more than 200 repeats induce cytosine methylation of CG dinucleotides within the repeat tract and also in the adjacent promoter region (Pieretti et al., 1991; Sutcliffe et al., 1992). The CGG expansion also triggers other epigenetic modifications that are characteristic of heterochromatin, such as, histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation and histone deacetylation (Coffee et al., 1999; Coffee et al., 2002) [histone modifications are reviewed in another article in this issue (Huynh & Casaccia)]. Although DNA methylation and histone modifications have a complex role in gene silencing, it has been suggested that DNA methylation is the key event that silences transcription of FMR1 (Pietrobono et al., 2002; Pietrobono et al., 2005). It is clear that loss of FMR1 activity is the primary mechanism responsible for mental retardation in FXS because a similar phenotype is produced by conventional mutations, such as, deletions or point mutations, that inactivate FMR1 (Gedeon et al., 1992; De Boulle et al., 1993). Howerver, CGG expansion is by far the commonest genetic lesion causing loss of FMR1 protein. Because FMR1 is on the X chromosome, the phenotype is less severe in females, depending on the ratio of inactivation for the wild-type versus the mutant X chromosome.

Both strands of the FMR1 5′ UTR are transcribed, as is true for many 5′ UTRs and for several other, if not all repeat expansion loci (Ladd et al., 2007) [discussed further below]. One possible mechanism for silencing is that bidirectional transcription of the expanded repeat leads to formation of double-stranded repeat-containing RNAs. Processing of these dsRNAs to small RNAs may recruit protein complexes that generate a repressive chromatin imprint (Martens et al., 2005; Ladd et al., 2007), although it remains to be established whether this mechanism of small RNA-mediated chromatin modification, initially characterized in yeast, is conserved in mammals. In addition to its effects on transcription, the expanded repeat also has an important post-transcriptional effect, which is to reduce the translational efficiency of FMR1 mRNA. The expanded CGG repeat may form a stable RNA secondary structure that inhibits ribosomal scanning of the 5′ UTR (Feng et al., 1995). While this effect may not be pertinent to FXS, where FMR1 transcripts are hardly produced, it may play a greater role in FXTAS, as discussed below.

Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive disorder that also involves gene silencing. Expansion of the GAA repeat causes a graded reduction of frataxin, a protein involved in iron homeostasis in mitochondria (Campuzano et al., 1997). Modest reductions of frataxin expression are well tolerated in individuals who are heterozygous for the GAA expansion (frequency ~1 in 120 in European populations), whereas homozygotes exhibit a critical reduction of frataxin that leads to mitochondrial impairment, juvenile-onset neurodegeneration, and cardiomyopathy [reviewed by (Pandolfo, 2008)].

The silencing of Frataxin by GAA expansion evidently occurs through two mechanisms. The repeat is positioned in intron 1, ~ 2 kilobases from the Frataxin promoter. When expanded, this repeat has a unique capability to form triplex DNA structures that inhibit transcriptional elongation (Bidichandani et al., 1998; Sakamoto et al., 1999; Grabczyk and Usdin, 2000). In parallel, it also has become clear that GAA expansions induce epigenetic changes that silence Frataxin expression (Saveliev et al., 2003; Herman et al., 2006; Greene et al., 2007; Al-Mahdawi et al., 2008). A recent study of FRDA cells has shown an interesting constellation of increased H3K9 trimethylation, recruitment of heterochromatin protein 1, reduced binding of the chromatin insulator protein CTCF, and increased antisense transcription, all in the region immediately downstream from the transcription start site (De Biase et al., 2009). Studies showing reversibility of Frataxin silencing with histone deacetylase inihibitors suggest that these epigenetic mechanisms have a critical role in causing the frataxin deficiency [discussed further below].

The expanded repeat in myotonic dystrophy is also associated with gene silencing. Highly expanded CTG repeats trigger DNA and histone H3K9 methylation in regions of DMPK that immediately flank the repeat tract (Otten and Tapscott, 1995; Filippova et al., 2001; Cho et al., 2005). In this case, however, the repeat is located in the final exon of DMPK,13 kilobase pairs distal to the promoter, and the expansion does not alter the activity of the DMPK promoter (Krahe et al., 1995). Moreover, despite the extreme length of DM1 expansions, which often extend for 5 to 15 kilobase pairs in affected tissues, the expansion does not block transcription elongation across the repeat (Krahe et al., 1995; Davis et al., 1997). Notably, because the density of genes in this region of chromosome 19 is high, the CTG repeat is close to regulatory elements that control a neighboring gene, which encodes the Six5 transcription factor. When expanded, the repeat does cause silencing of Six5 (Klesert et al., 1997; Thornton et al., 1997), and the mechanism once again appears to involve bidirectional transcription followed by endonucleolytic cleavage of dsRNAs to short RNAs (Cho et al., 2005). However, the studies of heterozygous Six5 knockout mice indicate that mono-allelic reduction of SIX5 expression is unlikely to have a major role in DM1 pathogenesis, although it may contribute to premature formation of ocular cataracts (Klesert et al., 2000; Sarkar et al., 2000).

The more important effect of the expanded DM1 repeat is post-transcriptional, in that nuclear export of mRNA with an expanded CUG repeat (CUGexp) is blocked. Although fully processed and polyadenylated, the mutant transcript is retained in the nucleus, where it accumulates in discrete foci at the edge of SC-35 domains (Taneja et al., 1995; Davis et al., 1997; Hamshere et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2007). A similar phenomenon of nuclear retention can be induced for other transcripts by inserting a CUGexp tract in the 3′ UTR (Amack et al., 1999; Mankodi et al., 2000). Notably, the formation of nuclear foci is markedly reduced by knock down of Muscleblind 1 (MBNL1) (Dansithong et al., 2005), the major CUGexp binding protein in muscle nuclei (Miller et al., 2000). This suggests that interaction of CUGexp RNA with MBNL1 protein is fundamentally involved in tethering the mutant RNA within the nucleus. However, the resulting decrease in translation of the mutant DMPK mRNA has a limited role, if any, in the pathogenesis of DM1. Indeed, the more important consequence is the effect on MBNL1 activity.

RNA dominance

DM1 is an autosomal dominant disease. Accordingly, the expected effect of retaining mutant mRNA in the nucleus, for affected individuals who are heterozygous for the expanded repeat, would approach a 50% reduction of DMPK protein. However, in knockout mice the DM protein kinase can be completely eliminated with only minor consequences for skeletal muscle (Jansen et al., 1996; Reddy et al., 1996), leaving geneticists to ponder how a non-coding repeat expansion could give rise to dominant disease if not by haploinsufficiency. Two lines of evidence now support the conclusion that symptoms of DM1 result from a toxic gain-of-function by transcripts that contain an expanded CUG repeat. First were observations that muscle, cardiac, and CNS features of DM1 could be reproduced by expression of CUGexp RNA in transgenic animals (Mankodi et al., 2000; Seznec et al., 2001; de Haro et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007; Orengo et al., 2008). Second was the discovery that a second form of myotonic dystrophy, caused by a non-coding repeat expansion in a different gene, also involves the accumulation of mutant RNA in nuclear foci. The expanded repeat in myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2) is a CCTG tetramer in the first intron of ZNF9, a gene encoding a multi-functional DNA and RNA binding protein (Liquori et al., 2001). Remarkably, DM2 expansions can attain lengths of up to 44 kilobases. The DM2 repeat is fully transcribed and the intron containing the CCUG expansion is properly excised (Margolis et al., 2006) but not rapidly degraded, producing toxic effects and having protein interactions similar to those observed with CUG repeats.

Mechanisms of RNA dominance in DM1

As mentioned above, the RNA binding protein MBNL1 has strong affinity for CUGexp RNA (Miller et al., 2000; Yuan et al., 2007; Warf and Berglund, 2007). When CUGexp RNA accumulates in the nucleus, MBNL1 is heavily recruited into RNA foci and depleted from the nucleoplasm (Miller et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2006). Because MBNL1 is a regulator of alternative splicing (Ho et al., 2004), its sequestration in foci leads to misregulated splicing for the exons that it normally controls. One example with a clear functional consequence relates to alternative splicing of Clcn1. This gene encodes a chloride ion channel that stabilizes the transmembrane potential during bouts of muscle activity. Alternative splicing of Clcn1 is misregulated in response to expression of CUGexp RNA or ablation of MBNL1, causing loss of channel activity (Mankodi et al., 2002; Charlet-B et al., 2002; Lueck et al., 2007). Loss of this channel causes membrane depolarization during muscle activity, triggering volleys of involuntary action potentials that cause a delay of muscle relaxation (myotonia). MBNL1 also regulates the alternative splicing of more than 50 other muscle-expressed genes (Du et al., 2010), though for many of these changes the effects of MBNL1 loss are not pronounced and the biological consequences of inappropriate exon skipping or inclusion are difficult to determine. Loss of MBNL1 also has other effects on gene expression, including alterations of transcription and possibly mRNA decay (Osborne et al., 2009). A plausible but still-unproven hypothesis is that the cumulative alterations of transcription, alternative splicing, and decay of many different MBNL1-dependent transcripts has a major contribution to the muscle and cardiac features of DM1.

While the hypothesis of MBNL1 sequestration has considerable experimental support, it clearly does not provide a unitary explanation for the disease. Most strikingly, MBNL1 knockout mice do not reproduce the developmental features of congenital DM1, nor do they display the severe muscle degeneration that occurs in individuals with adult-onset disease (Kanadia et al., 2003a). Also, it is clear that some transcripts whose expression is impacted by CUGexp RNA are neither direct nor indirect targets of MBNL1 (Osborne et al., 2009). Other candidates for involvement in DM1 include the two other members of the muscleblind-like family, MBNL2 and MBNL3 (Fardaei et al., 2002; Kanadia et al., 2003b). These proteins are closely related to MBNL1 and display similar CUGexp-binding activity. MBNL2 and MBNL3 can also become sequestered in nuclear RNA foci, making it likely that DM1 can produce combinatorial deficiency of all three muscleblind family members, depending on the amount of CUGexp RNA in relation to the supply of MBNL proteins in different cells and tissues.

Studies indicate that RNA dominance also causes important perturbations of cell signaling. For example, protein kinase C (PKC) is activated within 6 hours of expressing a non-coding CUGexp in mice (Kuyumcu-Martinez et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Orengo et al., 2008). While the mechanism responsible for sensing the repeat RNA and activating PKC have not been determined, one important downstream target has been identified – the RNA binding protein CUG-binding protein 1 (CUG-BP1) (Philips et al., 1998). This protein is subject to strong post-translational controls, in that phosphorylation can extend its half-life from 1 hr to > 4 hrs (Kuyumcu-Martinez et al., 2007). CUG-BP1 phosphorylation and stabilization has several consequences, including misregulated alternative splicing of several pre-mRNAs, as well as altered translation and decay of mRNAs that are CUG-BP1 binding targets (Savkur et al., 2001; Timchenko et al., 2001; Charlet-B et al., 2002; Timchenko et al., 2004; Ho et al., 2005). The complex effects of CUG-BP1 upregulation may be particularly important for the cardiac and developmental problems of DM1.

RNA dominance in Fragile X Tremor Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS)

In contrast to heterochromatin-mediated repression that is associated with “full mutations” of FMR1, shorter expansions of 55 to 200 repeats, and especially those in the range of 60 to 80 repeats, do not cause methylation or silencing, but instead are associated with production of a neurotoxic mRNA [reviewed by (Jacquemont et al., 2007)]. Thus, depending on the length of the repeat, CGG expansions in FMR1 can produce two neurological syndromes, FXS or FXTAS, whose clinical signs, neuropathologic features, and mechanistic bases seem entirely distinct. The late-onset neurodegenerative syndrome, FXTAS, is associated with increased levels of FMR1 mRNA, whereas levels of FMR1 protein are either unchanged or slightly reduced (Tassone et al., 2000; Kenneson et al., 2001; Tassone et al., 2004a; Tassone et al., 2004b). The altered relationship between transcript and protein levels is likely to result from the decreased translational efficiency of the CGG-expanded transcript.

The mechanism for increased accumulation of FMR1 mRNA in FXTAS is unknown. Possibly this alteration may represent a physiological compensation for decreased translational efficiency of CGG-expanded mRNA (Tassone et al., 2000; Kenneson et al., 2001). Alternatively, the expanded CGG repeat may act directly as an enhancer of FMR1 transcription. Whichever mechanism applies, it appears that the increased expression of the CGG-expanded transcript is deleterious in neurons and glia. FXTAS symptoms of tremor and ataxia typically develop in men after the age of 50, and are associated with ubiquitinated nuclear inclusions in specific populations of neurons and glia (Hagerman et al., 2001; Greco et al., 2002; Jacquemont et al., 2003). Similar inclusions are found in knockin mice that express Fmr1 with ~105 CGG repeats (Willemsen et al., 2003). Inclusion formation and degeneration can also be induced in Drosophila by expression of an untranslated (CGG)90 in retinal cells or neurons (Jin et al., 2003). In the latter model a CGG-repeat binding protein, Pur α, is recruited into nuclear inclusions, and the neurodegenerative process is alleviated by increased expression of Pur α protein (Jin et al., 2007). These observations raise the possibility of a protein sequestration mechanism, similar to that postulated for DM1.

Modulation of repeat instability by epigenetic changes

As discussed above, expanded repeats induce focal epigenetic changes that may repress the mutant allele or other genes in the vicinity. Studies of FXS suggest that the epigenetic changes, in turn, can modify the genetic stability of the expanded repeat. For example, an individual with FXS will typically show variability of repeat length in different somatic cells, but the instability that underlies this mosaicism occurs early in development. Later in fetal development the CGG expansion and flanking sequences become heavily methylated, and from this point the repeat length remains stable, even in clonal isolates of fibroblasts during extended periods of propagation (Wohrle et al., 1993). In contrast, individuals harboring a “premutation” allele of >130 repeats, or rare individuals with full expansions that remain unmethylated, will continue to show extensive somatic instability during postnatal life (Wohrle et al., 1998; Taylor et al., 1999). One possible explanation is that methylation has directly suppressed somatic instability by improving the fidelity of DNA replication or repair (Nichol and Pearson, 2002). Alternatively, somatic instability may depend, at least in part, on transcription of the repeat tract in one or both directions, in which case the epigenetic mark may stabilize the repeat by silencing the bidirectional transcription of FMR1. Whether DNA methylation has a general stabilizing influence on other repeat-containing loci has not been determined.

Opportunities for therapeutic intervention

Options for treating non-coding repeat expansion disorders are limited at present. No treatments are currently available that can delay the onset of symptoms or slow the disease progression. However, the elucidation of epigenetic and RNA dominant mechanisms has led to several novel therapeutic approaches [reviewed by (Di Prospero and Fischbeck, 2005)]. In the case of FRDA, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors offer one approach to reverse the epigenetic change, revert chromatin to an active conformation, and restore frataxin expression to levels that sustain neuronal survival. In support of this idea, histone H3 and H4 acetylation in chromatin near the GAA repeat was increased by HDAC inhibitor BML-210 (Herman et al., 2006). This compound and its derivatives were able to upregulate frataxin mRNA and protein in FRDA cells. Moreover, treatment of FRDA knockin mice with BML-210 derivatives resulted in increased histone H3 and H4 acetylation in chromatin near the expanded GAA repeat, accompanied by increased expression of frataxin mRNA and protein (Rai et al., 2008). While the pharmacologic manipulation of histone acetylation throughout the genome understandably raises concerns of toxicity, it appeared that short-term treatment was well tolerated in mice, perhaps because the effect of these compounds were relatively specific for HDAC3, an HDAC that may have a unique role in mediating the silencing of Frataxin (Xu et al., 2009).

Recently, a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) theory has been proposed in FXS pathogenesis (Bear et al., 2004). According to this theory, mGluR and FMR1 protein (FMRP) have antagonistic effects on activity-dependent translation at the synapse, with FMRP acting as a repressor of translation whereas mGluR signaling has the opposite effect of stimulating the translation of proteins involved in long term depression, a physiological marker of synaptic remodeling. Loss of FMRP would thus give rise to unopposed action of mGluR. Consistent with this theory, pharmacologic inhibitors of mGluR, or genetic knockdown of mGluR5, have favorably impacted the structural and behavioral features of FXS in animal models. Clinical trials are currently underway to test this strategy in patients with FXS [reviewed in (D'Hulst and Kooy, 2009)].

The therapeutic goal in DM1, in contrast, is to reduce the cellular accumulation of a toxic RNA or mitigate its harmful effects. For example, if the toxicity of DMPK transcripts is proportional to length of the expanded CUG repeat, then disease onset and progression may depend on growth of the CTG repeat in somatic cells of an individual. While this assumption has not been formally tested, if correct it would predict that methods to stabilize the repeat at a pre-symptomatic length, or to promote contraction rather than expansion events, would be preventative or therapeutic (Yang et al., 2003; Gomes-Pereira and Monckton, 2004). Agents that selectively alter the dynamics of repeat instability, however, have not yet been developed.

Another potential approach is to silence the transcription of the mutant DMPK allele. Theoretically this could be achieved by augmenting the expansion-induced epigenetic modifications, so that the heterochromatization spreads to include the elements that control DMPK transcription. However, this approach has not yet been tested.

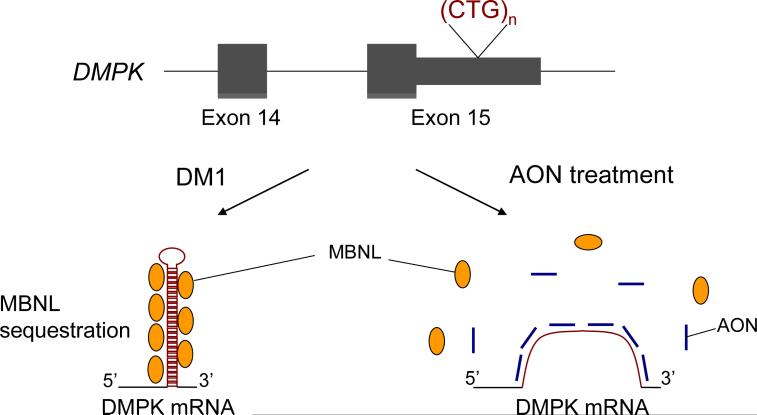

In terms of technologies that are currently available, a more feasible approach is to reduce RNA toxicity by accelerating the turnover of mutant DMPK mRNA. This has been achieved in cell culture systems by viral-mediated expression of antisense RNAs, short hairpin RNAs, or ribozymes, resulting in beneficial effects on cellular phenotypes (Furling et al., 2003; Langlois et al., 2005; Langlois et al., 2003). The obvious challenge for this approach is to avoid destruction of transcripts from the wild-type DMPK allele, which would further exacerbate the partial DMPK deficiency state that already exists in DM1. Another gene-therapy approach is to overexpress MBNL1 to levels that exceed the protein binding capacity of the toxic RNA (Kanadia et al., 2006). This method has shown promising effects in mouse models of DM1. A third approach is to neutralize the toxic RNA, using agents that inhibit the interaction of CUG expansion RNA with binding proteins (Gareiss et al., 2008; Pushechnikov et al., 2009; Warf et al., 2009). For example, morpholino oligomers are DNA analogues that bind to RNA targets with high affinity and specificity, without inducing target cleavage by RNase H (Summerton and Weller, 1997). A morpholino oligonucleotide consisting of CAG repeats was able to bind to CUGexp RNA and disrupt CUGexp-MBNL1 complexes in vitro (Wheeler et al., 2009). When injected into muscle tissue, this oligonucleotide dispersed the nuclear foci of CUGexp RNA, reversed the abnormalities of alternative splicing, and eliminated the myotonia in a transgenic mouse model of DM1. Interestingly, an oligonucleotide of similar sequence but utilizing a different chemistry (2′-O-methyl-phosphorothioate-modified RNA) showed remarkably selective knock down of transcripts from the mutant DMPK allele (Mulders et al., 2009). While the exact mechanism of this effect has not been determined, the therapeutic potential seems high, if it can be systemically delivered.

Conclusion

Short tandem repeats are ubiquitous features in the human genome. A tiny fraction of these repetitive elements are prone to become hypermutable and highly expanded. Determinants of this propensity are not understood, but may include length and sequence of the repeat, and genomic context in which it occurs (e.g., proximity to origins of replication, bidirectional transcription, and other factors). When located in non-coding sequence, these hyperexpanded repeats lead to neuropsychiatric symptoms through repeat-induced epigenetic silencing or RNA dominance. As the mechanisms underlying these disorders are clarified, the opportunity for therapeutic intervention becomes apparent. For many recessive disorders the primary focus of therapeutic development is on gene or protein replacement therapy. By contrast, the epigenetic mechanism for loss of function in FRDA is amenable to therapy by non-genomic methods. In addition, the RNA gain-of-function mechanism in DM1 may prove responsive to RNA targeted therapeutics.

Figure 2. Antisense oligonucleotides (AONs) rescue RNA-mediated toxicity in DM1.

Expanded CUG repeats in the mutant RNA form hairpin structures and sequester MBNL1 in the nucleus. Loss of functional MBNL1 causes misregulation of alternative splicing. AONs bind to expanded CUG repeats and release MBNL1, thereby restoring its function in splicing regulation.

Acknowledgements

This work comes from the Wellstone Muscular Dystrophy Cooperative Research Center at the University of Rochester (NIH U54NS48843) with support from the NIH (AR046806, AR48143) and the Muscular Dystrophy Association (M.N.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Mahdawi S, et al. The Friedreich ataxia GAA repeat expansion mutation induces comparable epigenetic changes in human and transgenic mouse brain and heart tissues. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:735–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amack JD, et al. Cis and trans effects of the myotonic dystrophy (DM) mutation in a cell culture model. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1975–1984. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer PO, Nukina N. The pathogenic mechanisms of polyglutamine diseases and current therapeutic strategies. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1737–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, et al. The mGluR theory of fragile X mental retardation. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:370–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidichandani SI, et al. The GAA triplet-repeat expansion in Friedreich ataxia interferes with transcription and may be associated with an unusual DNA structure. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:111–21. doi: 10.1086/301680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JD, et al. Molecular basis of myotonic dystrophy: expansion of a trinucleotide (CTG) repeat at the 3' end of a transcript encoding a protein kinase family member. Cell. 1992;68:799–808. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano V, et al. Frataxin is reduced in Friedreich ataxia patients and is associated with mitochondrial membranes. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1771–80. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano V, et al. Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science. 1996;271:1423–7. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlet-B N, et al. Loss of the muscle-specific chloride channel in type 1 myotonic dystrophy due to misregulated alternative splicing. Mol.Cell. 2002;10:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho DH, et al. Antisense transcription and heterochromatin at the DM1 CTG repeats are constrained by CTCF. Mol.Cell. 2005;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, et al. Histone modifications depict an aberrantly heterochromatinized FMR1 gene in fragile × syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:923–32. doi: 10.1086/342931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffee B, et al. Acetylated histones are associated with FMR1 in normal but not fragile X-syndrome cells. Nat Genet. 1999;22:98–101. doi: 10.1038/8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Hulst C, Kooy RF. Fragile X syndrome: from molecular genetics to therapy. J Med Genet. 2009;46:577–84. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.064667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dansithong W, et al. MBNL1 is the primary determinant of focus formation and aberrant insulin receptor splicing in DM1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5773–5780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein targets G quartet mRNAs important for neuronal function. Cell. 2001;107:489–99. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BM, et al. Expansion of a CUG trinucleotide repeat in the 3' untranslated region of myotonic dystrophy protein kinase transcripts results in nuclear retention of transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7388–7393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Biase I, et al. Epigenetic silencing in Friedreich ataxia is associated with depletion of CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor) and antisense transcription. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boulle K, et al. A point mutation in the FMR-1 gene associated with fragile X mental retardation. Nat Genet. 1993;3:31–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haro M, et al. MBNL1 and CUGBP1 modify expanded CUG-induced toxicity in a Drosophila model of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2138–2145. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prospero NA, Fischbeck KH. Therapeutics development for triplet repeat expansion diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:756–65. doi: 10.1038/nrg1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, et al. Aberrant alternative splicing and extracellular matrix gene expression in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:187–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardaei M, et al. Three proteins, MBNL, MBLL and MBXL, co-localize in vivo with nuclear foci of expanded-repeat transcripts in DM1 and DM2 cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:805–814. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.7.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, et al. Translational suppression by trinucleotide repeat expansion at FMR1. Science. 1995;268:731–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7732383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippova GN, et al. CTCF-binding sites flank CTG/CAG repeats and form a methylation-sensitive insulator at the DM1 locus. Nat Genet. 2001;28:335–343. doi: 10.1038/ng570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filla A, et al. The relationship between trinucleotide (GAA) repeat length and clinical features in Friedreich ataxia. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:554–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furling D, et al. Viral vector producing antisense RNA restores myotonic dystrophy myoblast functions. Gene Ther. 2003;10:795–802. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber KB, et al. Fragile X syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:666–72. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareiss PC, et al. Dynamic Combinatorial Selection of Molecules Capable of Inhibiting the (CUG) Repeat RNA-MBNL1 Interaction In vitro: discovery of lead compounds targeting myotonic dystrophy (DM1). J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16254–61. doi: 10.1021/ja804398y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel JR, Zoghbi HY. Diseases of unstable repeat expansion: mechanisms and common principles. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2005;6:743–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedeon AK, et al. Fragile X syndrome without CCG amplification has an FMR1 deletion. Nat Genet. 1992;1:341–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0892-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Pereira M, Monckton DG. Chemically induced increases and decreases in the rate of expansion of a CAG*CTG triplet repeat. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2865–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabczyk E, Usdin K. The GAA*TTC triplet repeat expanded in Friedreich's ataxia impedes transcription elongation by T7 RNA polymerase in a length and supercoil dependent manner. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:2815–22. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.14.2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco CM, et al. Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain. 2002;125:1760–1771. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene E, et al. Repeat-induced epigenetic changes in intron 1 of the frataxin gene and its consequences in Friedreich ataxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3383–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman PJ, Hagerman RJ. The fragile-X premutation: a maturing perspective. Am.J Hum.Genet. 2004;74:805–816. doi: 10.1086/386296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagerman RJ, et al. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–30. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamshere MG, et al. Transcriptional abnormality in myotonic dystrophy affects DMPK but not neighboring genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:7394–7399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper PS. Myotonic Dystrophy. W.B. Saunders Company; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Herman D, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors reverse gene silencing in Friedreich's ataxia. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:551–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TH, et al. Transgenic mice expressing CUG-BP1 reproduce splicing mis-regulation observed in myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1539–1547. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho TH, et al. Muscleblind proteins regulate alternative splicing. EMBO J. 2004;23:3103–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, et al. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7746–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter A, et al. The correlation of age of onset with CTG trinucleotide repeat amplification in myotonic dystrophy. J Med Genet. 1992;29:774–779. doi: 10.1136/jmg.29.11.774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, et al. Fragile-X syndrome and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome: two faces of FMR1. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:45–55. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemont S, et al. Fragile X premutation tremor/ataxia syndrome: molecular, clinical, and neuroimaging correlates. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:869–78. doi: 10.1086/374321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen G, et al. Abnormal myotonic dystrophy protein kinase levels produce only mild myopathy in mice. Nat Genet. 1996;13:316–324. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 1 associated with nuclear foci of mutant RNA, sequestration of muscleblind proteins, and deregulated alternative splicing in neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3079–88. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, et al. Pur alpha binds to rCGG repeats and modulates repeat-mediated neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Neuron. 2007;55:556–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin P, et al. RNA-mediated neurodegeneration caused by the fragile X premutation rCGG repeats in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;39:739–747. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanadia RN, et al. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003a;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanadia RN, et al. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;103:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanadia RN, et al. Developmental expression of mouse muscleblind genes Mbnl1, Mbnl2 and Mbnl3. Gene Expr.Patterns. 2003b;3:459–462. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenneson A, et al. Reduced FMRP and increased FMR1 transcription is proportionally associated with CGG repeat number in intermediate-length and premutation carriers. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1449–1454. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.14.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesert TR, et al. Mice deficient in Six5 develop cataracts: implications for myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;25:105–109. doi: 10.1038/75490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesert TR, et al. Trinucleotide repeat expansion at the myotonic dystrophy locus reduces expression of the DMAHP gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:402–406. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahe R, et al. Effect of myotonic dystrophy trinucleotide repeat expansion on DMPK transcription and processing. Genomics. 1995;28:1–14. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyumcu-Martinez NM, et al. Increased Steady-State Levels of CUGBP1 in Myotonic Dystrophy 1 Are Due to PKC-Mediated Hyperphosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2007;28:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd PD, et al. An antisense transcript spanning the CGG repeat region of FMR1 is upregulated in premutation carriers but silenced in full mutation individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3174–87. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois MA, et al. Cytoplasmic and nuclear retained DMPK mRNAs are targets for RNA interference in myotonic dystrophy cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16949–16954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois MA, et al. Hammerhead ribozyme-mediated destruction of nuclear foci in myotonic dystrophy myoblasts. Mol Ther. 2003;7:670–80. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, et al. Failure of MBNL1-dependent postnatal splicing transitions in myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2087–97. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liquori CL, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron 1 of ZNF9. Science. 2001;293:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1062125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueck JD, et al. Muscle chloride channel dysfunction in two mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. J Gen.Physiol. 2007;129:79–94. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankodi A, et al. Myotonic dystrophy in transgenic mice expressing an expanded CUG repeat. Science. 2000;289:1769–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankodi A, et al. Expanded CUG repeats trigger aberrant splicing of ClC-1 chloride channel pre-mRNA and hyperexcitability of skeletal muscle in myotonic dystrophy. Mol.Cell. 2002:35–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis JM, et al. DM2 intronic expansions: evidence for CCUG accumulation without flanking sequence or effects on ZNF9 mRNA processing or protein expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1808–1815. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens JH, et al. The profile of repeat-associated histone lysine methylation states in the mouse epigenome. EMBO J. 2005;24:800–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, et al. Recruitment of human muscleblind proteins to (CUG)(n) expansions associated with myotonic dystrophy. EMBO J. 2000;19:4439–4448. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulders SA, et al. Triplet-repeat oligonucleotide-mediated reversal of RNA toxicity in myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13915–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905780106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol K, Pearson CE. CpG methylation modifies the genetic stability of cloned repeat sequences. Genome Res. 2002;12:1246–1256. doi: 10.1101/gr.74502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo JP, et al. Expanded CTG repeats within the DMPK 3' UTR causes severe skeletal muscle wasting in an inducible mouse model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2646–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708519105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne RJ, et al. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional impact of toxic RNA in myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1471–81. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otten AD, Tapscott SJ. Triplet repeat expansion in myotonic dystrophy alters the adjacent chromatin structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5465–5469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfo M. Friedreich ataxia. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1296–303. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.10.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CE, et al. Repeat instability: mechanisms of dynamic mutations. Nat.Rev.Genet. 2005;6:729–742. doi: 10.1038/nrg1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips AV, et al. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieretti M, et al. Absence of expression of the FMR-1 gene in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;66:817–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90125-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobono R, et al. Quantitative analysis of DNA demethylation and transcriptional reactivation of the FMR1 gene in fragile X cells treated with 5-azadeoxycytidine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3278–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobono R, et al. Molecular dissection of the events leading to inactivation of the FMR1 gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:267–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushechnikov A, et al. Rational design of ligands targeting triplet repeating transcripts that cause RNA dominant disease: application to myotonic muscular dystrophy type 1 and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9767–79. doi: 10.1021/ja9020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai M, et al. HDAC inhibitors correct frataxin deficiency in a Friedreich ataxia mouse model. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S, et al. Mice lacking the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase develop a late onset progressive myopathy. Nat Genet. 1996;13:325–334. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto N, et al. Sticky DNA: self-association properties of long GAA.TTC repeats in R.R.Y triplex structures from Friedreich's ataxia. Mol Cell. 1999;3:465–75. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80474-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar PS, et al. Heterozygous loss of Six5 in mice is sufficient to cause ocular cataracts. Nat Genet. 2000;25:110–114. doi: 10.1038/75500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saveliev A, et al. DNA triplet repeats mediate heterochromatin-protein-1-sensitive variegated gene silencing. Nature. 2003;422:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature01596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur RS, et al. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seznec H, et al. Mice transgenic for the human myotonic dystrophy region with expanded CTG repeats display muscular and brain abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2717–2726. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J, Diamond MI. Polyglutamine diseases: emerging concepts in pathogenesis and therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:R115–23. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm213. Spec No. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KP, et al. Defining early steps in mRNA transport: mutant mRNA in myotonic dystrophy type I is blocked at entry into SC-35 domains. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:951–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerton J, Weller D. Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties. Antisense Nucleic Acid Drug Dev. 1997;7:187–195. doi: 10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe JS, et al. DNA methylation represses FMR-1 transcription in fragile X syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:397–400. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.6.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja KL, et al. Foci of trinucleotide repeat transcripts in nuclei of myotonic dystrophy cells and tissues. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:995–1002. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.6.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, et al. Intranuclear inclusions in neural cells with premutation alleles in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J Med Genet. 2004a;41:e43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, et al. Elevated levels of FMR1 mRNA in carrier males: a new mechanism of involvement in the fragile-X syndrome. Am.J Hum.Genet. 2000;66:6–15. doi: 10.1086/302720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassone F, et al. FMR1 RNA within the intranuclear inclusions of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). RNA Biol. 2004b;1:103–5. doi: 10.4161/rna.1.2.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AK, et al. Tissue heterogeneity of the FMR1 mutation in a high-functioning male with fragile X syndrome. Am.J Med.Genet. 1999;84:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton CA, et al. Expansion of the myotonic dystrophy CTG repeat reduces expression of the flanking DMAHP gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:407–409. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timchenko NA, et al. Molecular basis for impaired muscle differentiation in myotonic dystrophy. Mol.Cell Biol. 2001;21:6927–6938. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.20.6927-6938.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timchenko NA, et al. Overexpression of CUG triplet repeat-binding protein, CUGBP1, in mice inhibits myogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13129–13139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilfidis C, et al. Correlation between CTG trinucleotide repeat length and frequency of severe congenital myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1992;1:192–195. doi: 10.1038/ng0692-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkerk AJ, et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65:905–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90397-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GS, et al. Elevation of RNA-binding protein CUGBP1 is an early event in an inducible heart-specific mouse model of myotonic dystrophy. J Clin.Invest. 2007;117:2802–2811. doi: 10.1172/JCI32308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warf MB, Berglund JA. MBNL binds similar RNA structures in the CUG repeats of myotonic dystrophy and its pre-mRNA substrate cardiac troponin T. RNA. 2007;13:2238–51. doi: 10.1261/rna.610607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warf MB, et al. Pentamidine reverses the splicing defects associated with myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18551–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TM, et al. Reversal of RNA dominance by displacement of protein sequestered on triplet repeat RNA. Science. 2009;325:336–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1173110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen R, et al. The FMR1 CGG repeat mouse displays ubiquitin-positive intranuclear neuronal inclusions; implications for the cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:949–959. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AJ, Paulson HL. Polyglutamine neurodegeneration: protein misfolding revisited. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, et al. Mitotic stability of fragile X mutations in differentiated cells indicates early post-conceptional trinucleotide repeat expansion. Nat Genet. 1993;4:140–2. doi: 10.1038/ng0693-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohrle D, et al. Unusual mutations in high functioning fragile X males: apparent instability of expanded unmethylated CGG repeats. J Med.Genet. 1998;35:103–111. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.2.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, et al. Chemical probes identify a role for histone deacetylase 3 in Friedreich's ataxia gene silencing. Chem Biol. 2009;16:980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, et al. Replication inhibitors modulate instability of an expanded trinucleotide repeat at the myotonic dystrophy type 1 disease locus in human cells. Am.J Hum.Genet. 2003;73:1092–1105. doi: 10.1086/379523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, et al. Muscleblind-like 1 interacts with RNA hairpins in splicing target and pathogenic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5474–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]