Abstract

Objective

To determine the role of Mcp-1 on the progression of visceral fat-induced atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results

Visceral fat inflammation was induced by transplantation of perigonadal fat. To determine if recipient Mcp-1 status affected atherosclerosis induced by inflammatory fat, ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice underwent visceral fat transplantation. Intravital microscopy was used to study leukocyte-endothelial interactions. To study the primary tissue source of circulating Mcp-1, both fat and bone marrow transplantation experiments were used. Transplantation of visceral fat increased atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice but had no effect on atherosclerosis in ApoE−/−, Mcp-1−/− mice. Intravital microscopy revealed increased leukocyte attachment to the endothelium in ApoE−/− mice compared to ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice after receiving visceral fat transplants. Transplantation of visceral fat increased plasma Mcp-1 although donor adipocytes were not the source of circulating Mcp-1 since no Mcp-1 was detected in plasma from ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice transplanted with Wt fat, indicating recipient Mcp-1-producing cells were affecting the atherogenic response to the fat transplantation. Consistently, transplantation of Mcp-1−/− fat to ApoE−/− mice did not lead to atheroprotection in recipient mice. Bone marrow transplantation between Wt and Mcp-1−/− mice indicated the primary tissue source of circulating Mcp-1 was the endothelium.

Conclusions

Recipient Mcp-1 deficiency protects against atherosclerosis induced by transplanted visceral adipose tissue.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, endothelium, adipocyte, cytokine, obesity

Obesity is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease 1, 2. This risk is primarily due to central, or visceral adiposity, and is associated with systemic markers of inflammation 3, 4. Features of adipose depots that may confer increased cardiovascular risk include leukocyte infiltration with evidence of increased adipose tissue macrophage activity 5–7. Chemokines such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (Mcp-1) have been shown to be elevated in plasma and adipose tissue of obese humans and animals 8, 9. Mcp-1 expression has been shown to be higher in visceral adipose tissue depots compared to subcutaneous depots and Mcp-1 may play a role in regulating inflammatory characteristics of adipose tissue 10–12. Visceral adipose tissue transplantation leads to heightened inflammation in the fat transplant and is sufficient to promote atherosclerosis in atherosclerotic-prone mice 13. However, the specific mediator(s) of increased atherosclerosis in this model of inflammatory fat are unknown.

In the present study, we determined the role of Mcp-1 in atherosclerosis induced by visceral adipose tissue transplantation.

METHODS

Mice

8–10 week old wild-type (Wt) and Mcp-1 deficient (Mcp-1−/−), 8 week old apolipoprotein E deficient (ApoE−/−) and combined apolipoprotein E deficient, Mcp-1 deficient (ApoE−/−, Mcp-1−/−) mice were used, all on the C57BL/6J background strain. Original breeding pairs were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Double-knock-out ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice were generated by first crossing ApoE−/− mice to Mcp-1−/− mice and then intercrossing ApoE+/−,Mcp-1+/− breeders to produce ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1+/+ (abbreviated as ApoE−/−) littermates. Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities and were fed a normal chow diet (Laboratory Rodent Diet 5001, 5% fat, LabDiet, New Brunswick, NJ) throughout the study. The procedures conform with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and were approved by the University of Michigan Committee on Use and Care of Animals.

Adipose Transplantation

8 week old ApoE−/−, ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/−, Wt and Mcp-1−/− mice were used as recipients for fat transplantation from 10 week old Wt or Mcp-1−/− donor mice. All mice used for atherosclerotic studies were males. Fat transplantation was performed as previously described 13. Briefly, all mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (67 mg/kg), visceral (perigonadal) adipose tissue was removed from donors, weighed, and implanted subcutaneously into 4 dorsal incisions for a total of 424±16 mg of fat per recipient. 6-0 nylon filament was used for wound closure. An additional group of ApoE−/− mice received an equivalent amount of subcutaneous inguinal fat (440±35 mg) from Wt donor mice using the same protocol. The transplanted visceral fat represents approximately 60% increase in total visceral fat mass, based on previous quantitation of fat depots 14 while the transplanted subcutaneous fat represents approximately 50% increase in the total amount of subcutaneous fat in an adult, 25 g body-weight, chow-fed C57BL/6 mouse (subcutaneous estimate based on calculation of total fat mass minus visceral and brown fat mass)14.

Bone Marrow Transplantation

Bone marrow transplantation (BMT) was performed as previously described 15. Wt mice were used as recipients for Wt and Mcp-1−/− donor mice, and Mcp-1−/− mice were used as recipients for Wt donor mice. Each recipient mouse was irradiated (2 × 650 rad [0.02 × 6.5 Gy]) and injected with 4 × 106 bone marrow cells via the tail vein. To induce an acute inflammatory reaction, BMT recipients were injected intraperitoneally with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (1 mg/kg), and blood samples were collected 6 hours post-LPS injection. A subset of bone-marrow transplanted Wt and Mcp-1−/− mice, receiving Mcp-1−/− and Wt marrow, respectively, underwent fat transplantation 4 wks after BMT, with all mice receiving Mcp-1-deficient visceral adipose tissue.

Measurements of cytokines, insulin, glucose, lipids and body fat percent

Blood samples from mice were collected by retro-orbital bleeding using capillary tubes. Fat homogenates were prepared at sacrifice from 100 mg of transplanted adipose tissue as described earlier 13. A commercially available murine ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were used to measure Mcp-1, osteopontin and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) levels. Glucose was measured after over-night fast with a glucometer using test strips (Ascensia ® Contour, Bayer HealthCare LLC, Mishawaka, IN) 8 weeks after the fat transplantation. At the same time point, fasted insulin levels were measured with an ELISA kit (Crystal Chem Inc., Downers Grove, IL). Serum collected at sacrifice after over-night fast was used to measure non-esterified fatty acids (Wako, Richmond, VA) and cholesterol levels (Wako, Richmond, VA) with colorimetric assays. Body fat percent was measured using a Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scanner Lunar PIXImus2 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

Atherosclerosis Quantitation

At the time of sacrifice (24 wks of age, 16 wks after fat transplantation), all ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/− mice (both fat-transplanted and non-transplanted control mice) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (67 mg/kg), perfused with saline at physiologic pressure and then fixed using formalin with a 25-gauge needle inserted into the left ventricle, at a rate of 1 ml/min. The carcass was fixed in formalin and the arterial tree was then meticulously dissected and placed in 70% ethanol. After staining with Oil-Red-O and pinning on wax, the surface area occupied by atherosclerosis was quantitated at the aortic arch and major branches, including the brachiocephalic, carotid, and subclavian arteries to the second bifurcation using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics). The lesion area was expressed as a percentage of total surface area examined. For analysis of the aortic root, hearts were removed from formalin fixed carcasses at the time of arterial dissection and embedded in paraffin 16, 17. Serial sections were cut at 5µm intervals to obtain representative sections at the level of the aortic valve leaflets.

Immunohistochemistry

Macrophages in adipose tissue and aortic root cross-sections were identified using a rat anti-mouse Mac-3 monoclonal antibody (1:200 and 1:100 dilution, respectively; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Mac-3 (a.k.a. CD107b and LAMP-2) is expressed on lysosomal membranes and the plasma membrane of macrophages 18, and has been previously used to detect macrophages on aortic valves 17 and adipose tissue 19. Stained cells in adipose tissue were expressed as a percentage of total cells. In the aortic root, the Mac-3 positive lesion area was quantitated in randomly chosen sections between groups using the valve leaflet as a landmark using image analysis software (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics) with the observer blinded to mouse genotype.

Intravital Microscopy

The intravital microscopy model consisted of a Nikon FN1 fixed stage microscopy system with X-cite for epi-fluorescence, Photometrics Coolsnap Cacade 512B color digital camera system, and MetaMorph premier software package and computer system. Intravital microscopy was used to analyze the microcirculation of the cremaster muscle in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/− mice following fat transplantation. For analysis of cremaster vessels, mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (67 mg/kg) and positioned supine securely with tape. An incision was made in the scrotal skin to expose the left cremaster muscle, which was then removed from the surrounding fascia. A lengthwise incision was made on the ventral surface of the cremaster muscle, and the testicle and epididymis were separated from the underlying muscle and reintroduced into the abdominal cavity. The muscle was then spread over an optically clear viewing pedestal and secured along the edges with 3-0 suture. The exposed tissue was superfused with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) 20. The cremaster microcirculation was observed through the intravital microscope with a 10× eyepiece and 40× objective lens. To visualize white blood cells, rhodamine 6G (0.3 mg/kg) (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) was injected into the tail vein immediately prior to visualization. At this dose, rhodamine 6G labels leukocytes and allows detection of all rolling leukocytes. Rhodamine 6G-associated fluorescence was visualized by epi-illumination with a 510–560 nm emission filter. Single unbranched venules (20–40 µm in diameter) were selected for study and images of the microcirculation were digitally recorded. Firm leukocyte adhesion was detected if leukocytes remained stationary for 30 seconds or longer 21. Three venules were analyzed for each mouse.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM. For each analysis, data was normally distributed. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by the Student’s t test. P<0.05 was considered significant. The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity. All authors have read and agree with the manuscript as written.

RESULTS

Effect of Mcp-1 deficiency on visceral fat-induced atherosclerosis

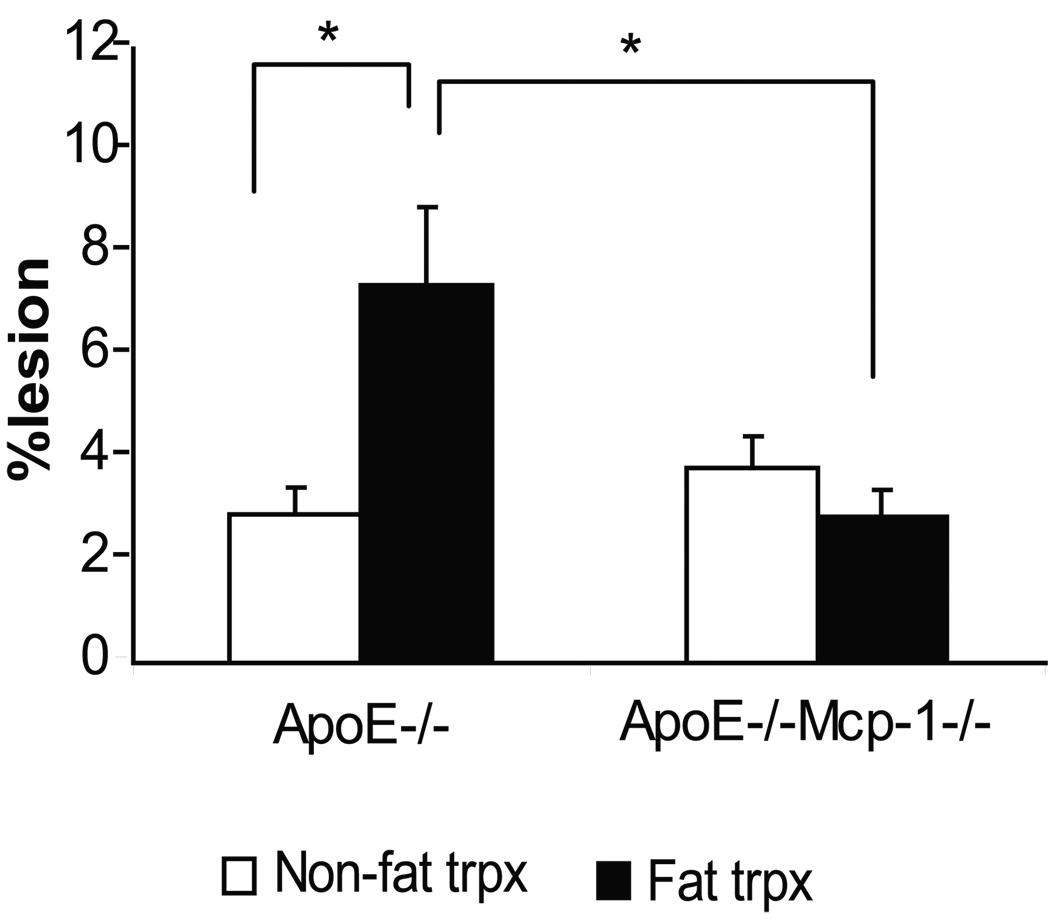

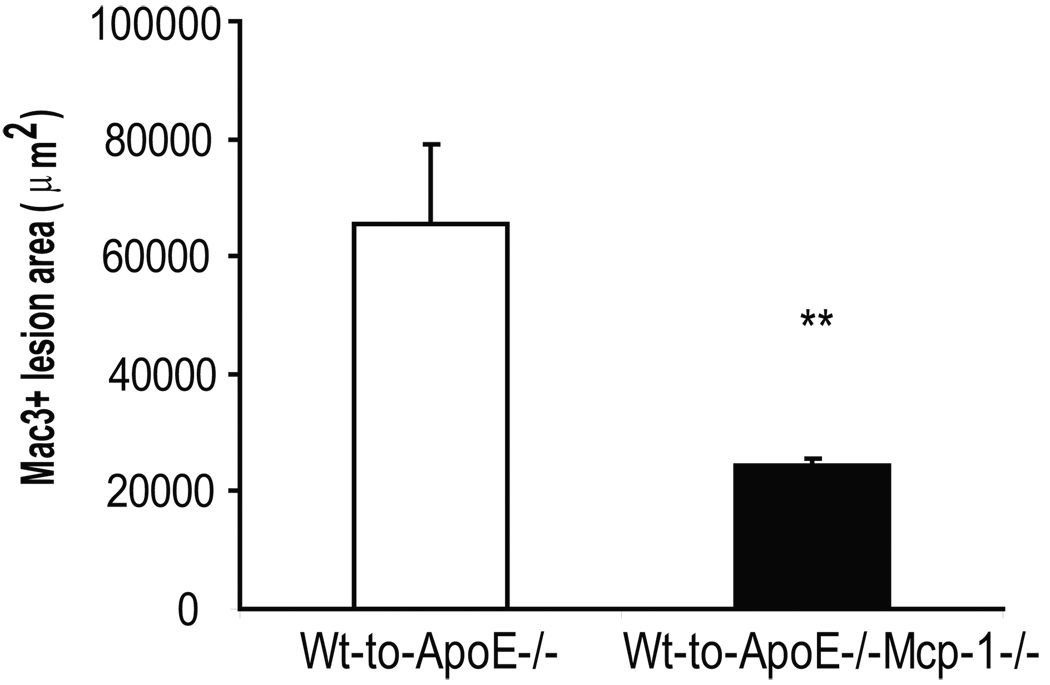

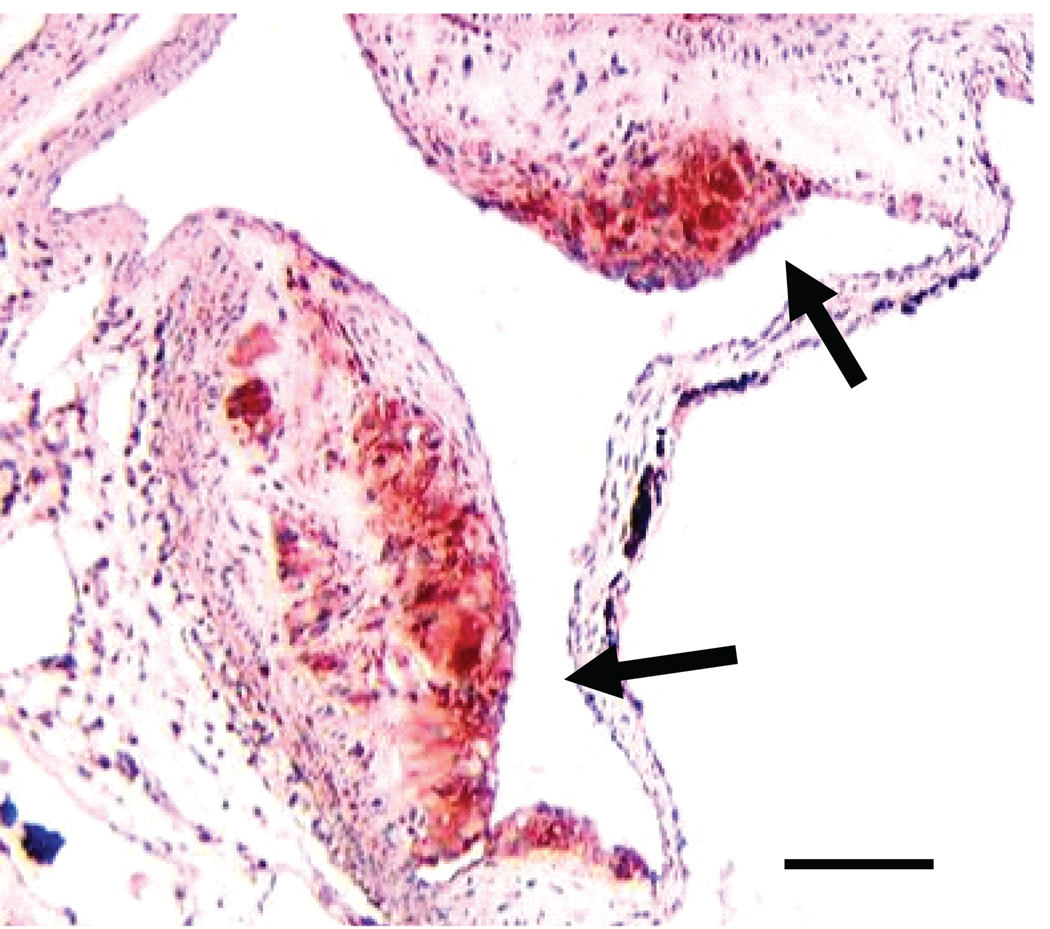

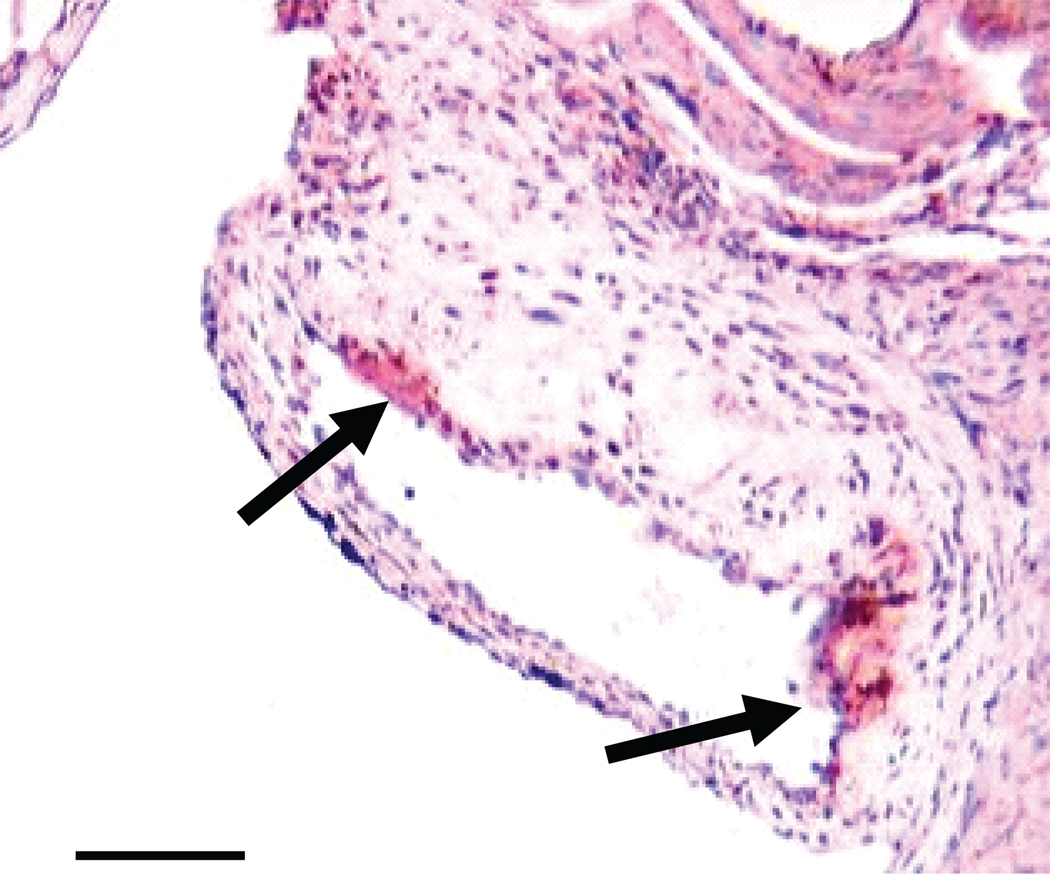

To determine if Mcp-1 deficiency would attenuate the proatherogenic effect of inflammatory visceral fat, we quantified atherosclerosis by Oil-red-O staining of the aortic trees in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− (n=6) and ApoE−/− (n=8) mice that received Wt fat transplants. When comparing non-transplanted ApoE−/− mice (n=5) to their fat transplanted littermates, there was a significant increase in atherosclerosis in transplanted ApoE−/− mice (Figure 1). However, the ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice were completely protected against the increase in atherosclerosis induced by inflammatory visceral fat when compared to non-transplanted littermate ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice (n=10) (Figure 1). Macrophage-rich lesion area determined from aortic root cross sections was also markedly reduced in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat compared to ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat (24317±1140 vs. 65584±13470 µm2, p=0.002) (Figure 2). Fasting glucose (226.5±13.9 vs. 186.8±14.0 mg/dl, p=NS), insulin (2.00±0.94 vs. 1.96±0.55 ng/ml, p=NS) and adiposity (fat%; 12.52±0.82 vs. 13.30±0.56%, p=NS) in fat transplanted ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat were not different between the groups 8 weeks post-operatively.

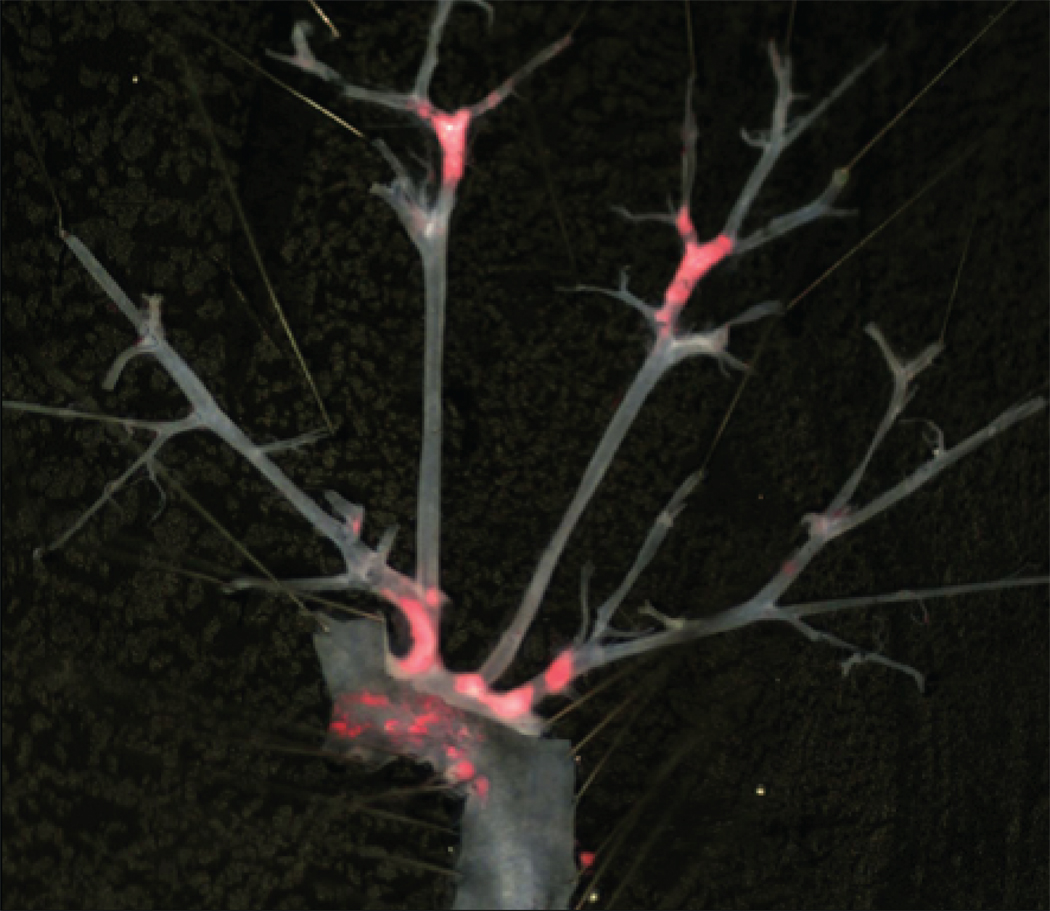

Figure 1.

Inflammatory visceral fat induced atherosclerosis. A) Comparison of non-transplanted ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice (white bars) to the age-matched, genotype-matched ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice that underwent fat transplantation receiving Wt visceral fat (black bars). *p<0.05. Representative en face view of aortic tree stained with Oil-Red-O of B) Wt-to-ApoE−/− mouse, and C) Wt-to-ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mouse

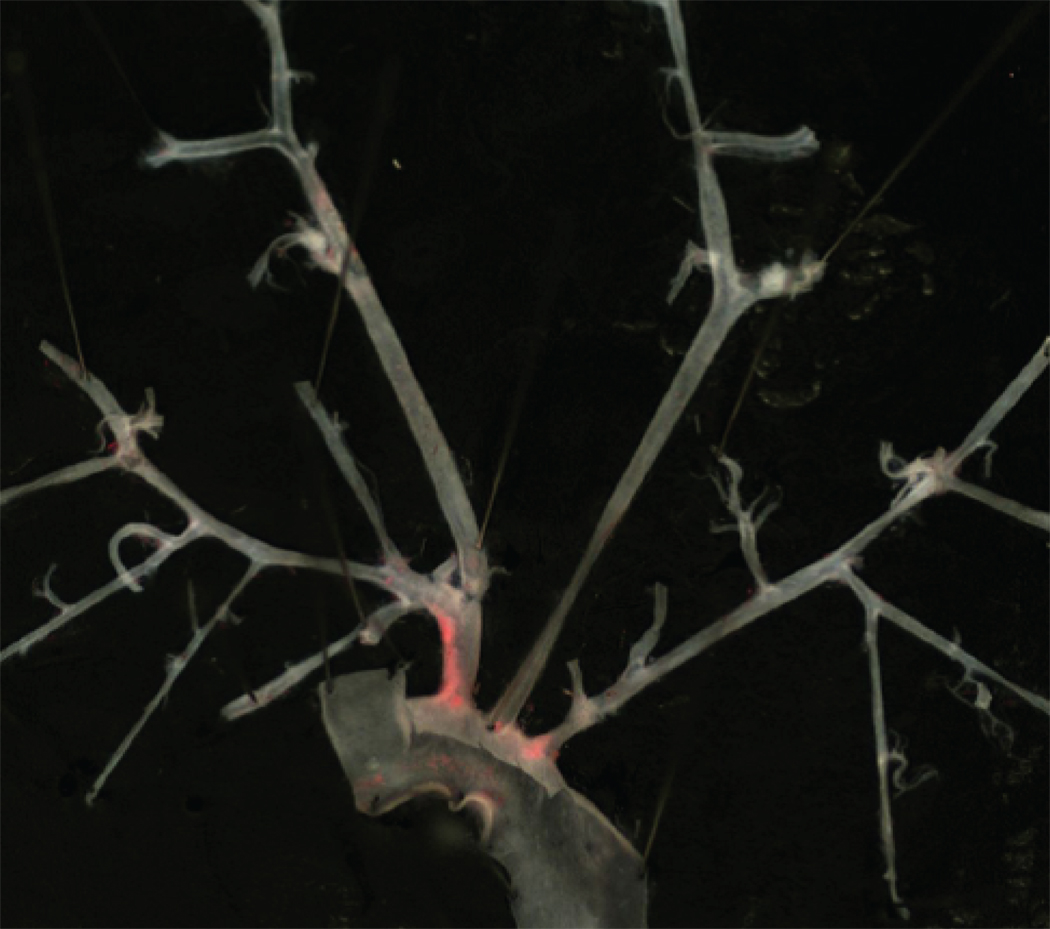

Figure 2.

A) Macrophage-rich lesion area in fat transplanted ApoE−/− (white bar) and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− (black bar) mice. p=0.002. Representative picture of aortic root from B) Wt-to-ApoE−/− mouse and C) Wt-to-ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mouse. Magnification 10×, staining with Mac3 antibody, scale bar 500 µm, arrows showing stained area.

We also quantified atherosclerotic lesion area in ApoE−/− mice that received Mcp-1−/− fat transplants (n=8). These mice displayed similar findings to those observed in ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat, i.e. their surface lesion area was significantly greater compared to non-transplanted control ApoE−/− mice (7.5±1.1 vs. 2.9±0.5, respectively, p<0.05) and they developed similar amount of atherosclerosis as ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat (7.5±1.1 vs. 7.4±1.5 %, respectively, p=NS), Thus, the lack of Mcp-1 in donor adipocytes does not explain the decrease in the atherosclerotic burden induced by fat transplantation. In non-transplanted control ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice, which were fed the same normal chow diet as transplanted mice, no differences in atherosclerotic lesion area were detected (2.9±0.5 vs. 3.7±0.6 %, respectively, p=NS). Total cholesterol and free fatty acids were measured at sacrifice from all fat transplanted and control mice. There was no difference in cholesterol between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat (398.2±32.8 vs. 508.6±58.8 mg/dl, respectively, p=NS), or between ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat and ApoE−/− mice receiving Mcp-1−/− fat (398.2±32.8 vs. 452.2±21.1 mg/dl, respectively, p=NS). There was no difference in free fatty acids between the ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat (1.52±0.12 vs. 1.92±0.13 mmol/l, respectively, p=NS), or between ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat and ApoE−/− mice receiving Mcp-1−/− fat (1.52±0.12 vs. 1.56±0.05 mmol/, respectively, p=NS).

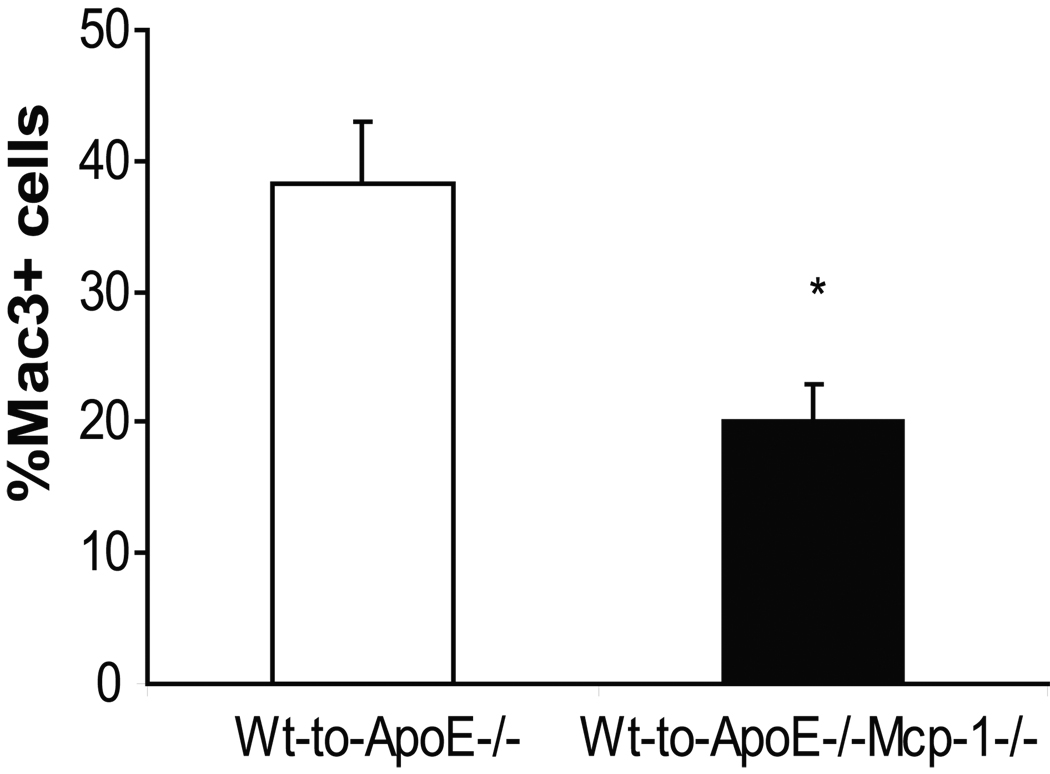

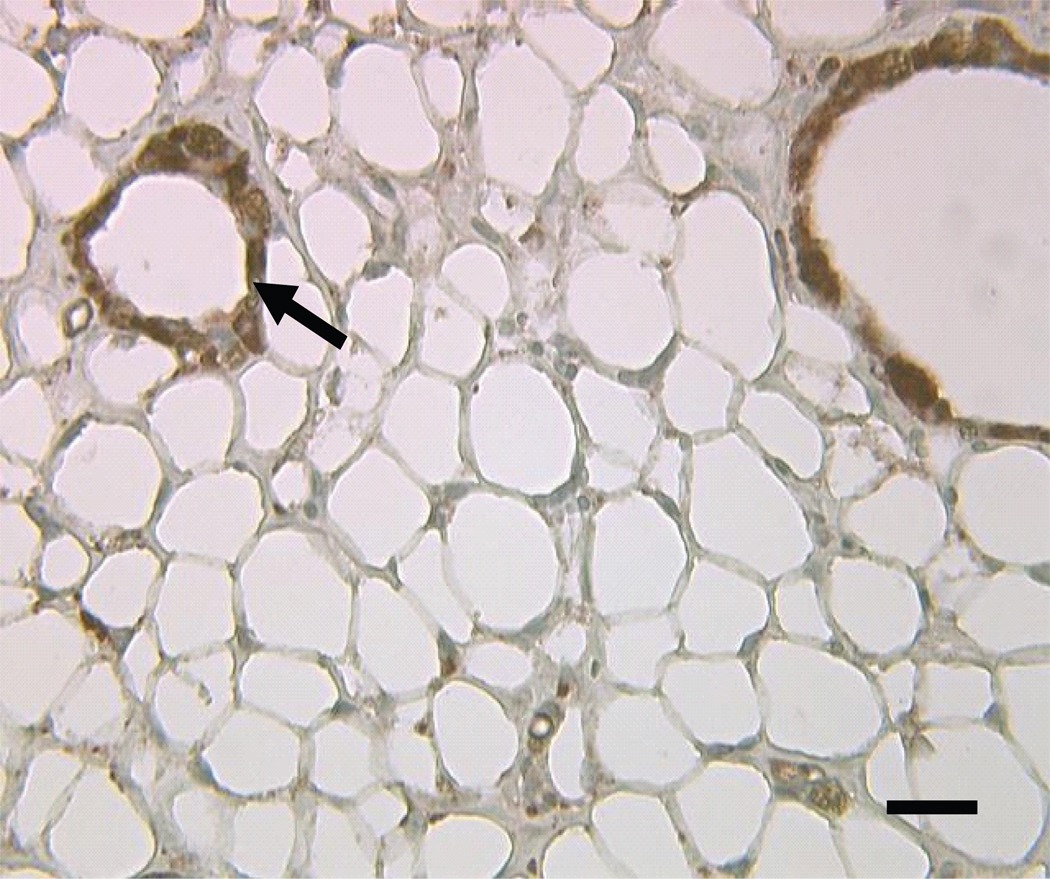

Effect of Mcp-1 deficiency on fat inflammation

To characterize the role of Mcp-1 deficiency on inflammation in transplanted visceral fat pads, transplanted fat pads were removed from ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice at the time of sacrifice and analyzed for macrophage content. Wt fat transplants removed from ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice contained a reduced percentage of macrophages compared to Wt fat transplants removed from ApoE−/− mice (Figure 3). The Mcp-1−/− fat pads transplanted to ApoE−/− mice were also analyzed for macrophage content and no differences were found in macrophage content when compared to Wt fat pads analyzed from ApoE−/− mice (26.1±5.6 vs. 38.2±4.9, respectively, p=NS). Thus, the adipocyte Mcp-1 status does not regulate macrophage infiltration into fat in this model.

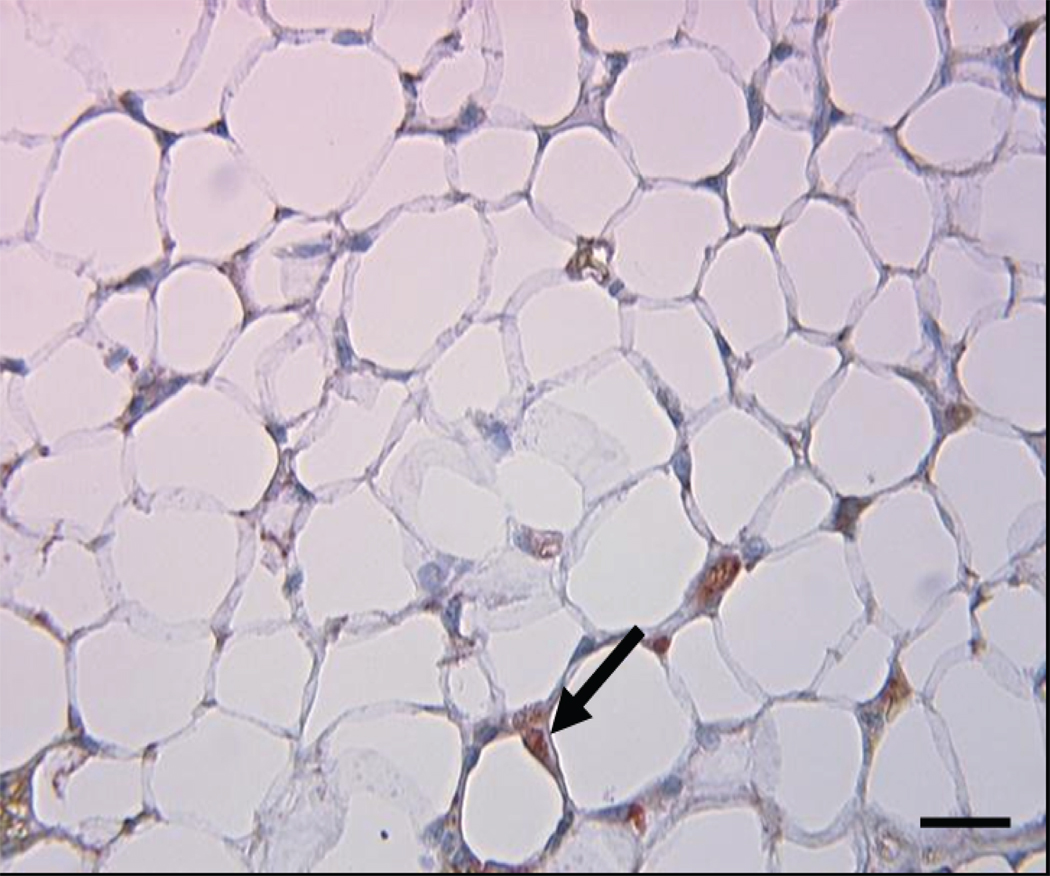

Figure 3.

Macrophage content of transplanted adipose tissue. A) Macrophage content of transplanted fat in ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat (white bar) and in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat (black bar). *p<0.05. Representative cross sections of transplanted adipose tissue from B) ApoE−/− recipient mouse, and C) ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− recipient mouse. Staining with Mac3 antibody, magnification 40×, scale bar 100 µm, arrows showing stained cells.

Effect of fat transplantation on leukocyte-endothelial interactions

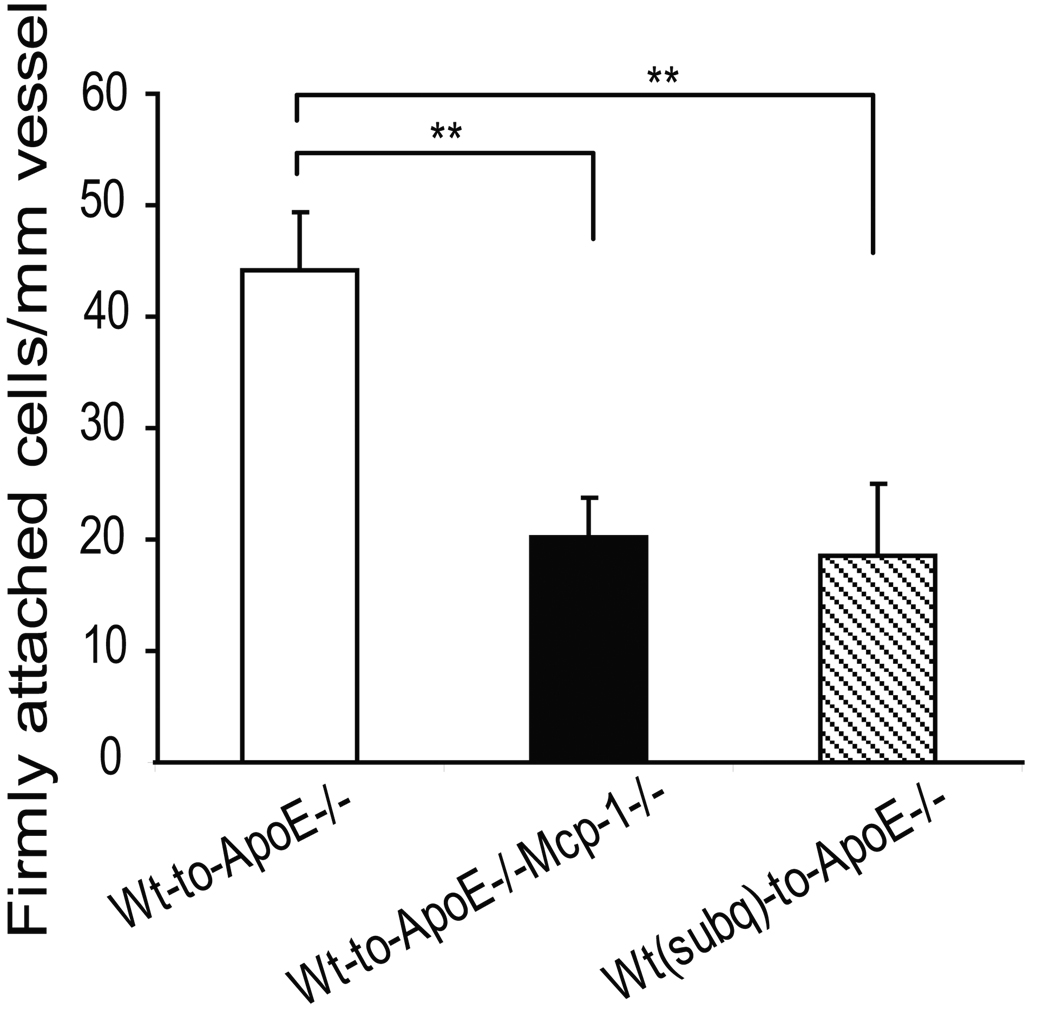

To determine if visceral fat transplantation was associated with increased systemic adhesive interactions between the endothelium and leukocytes, intravital microscopy was used to visualize interactions between leukocytes and endothelial cells in ApoE−/−, Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/− mice following visceral fat transplantation. Fat transplanted ApoE−/−, Mcp-1−/− mice displayed significantly less leukocyte firm attachment compared to fat transplanted ApoE−/− mice (20.3±3.5 vs. 44.1±5.3 firmly attached cells/mm vessel, p=0.002) (Figure 4).

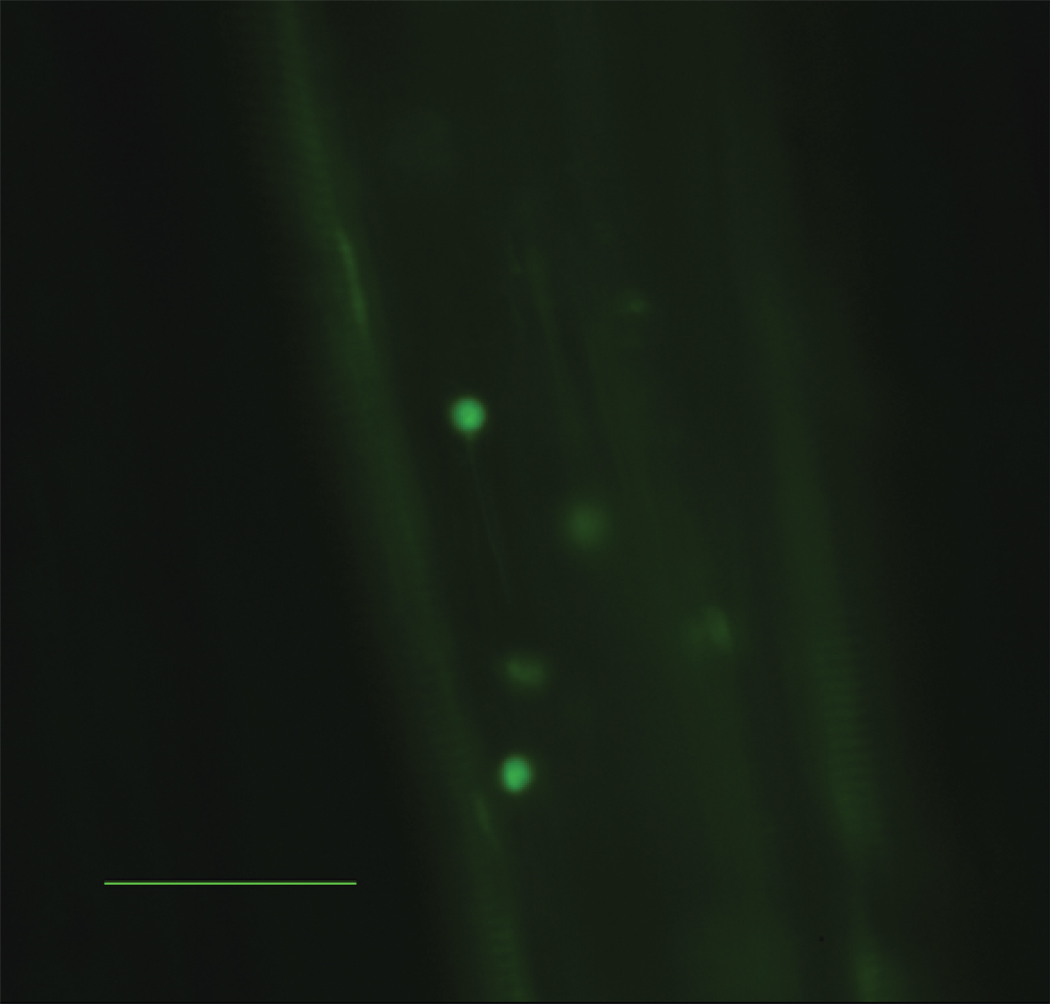

Figure 4.

Number of firmly attached leukocytes per length of vessel identified by intravital microscopy. A) ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt visceral fat (white bar) had significantly more firm attachment compared to ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt visceral fat (black bar) and ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt subcutaneous fat (striped bar). n=3 per group, **p≤0.01. Representative still pictures of adherent cells from B) ApoE−/− and C) ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt visceral fat, and D) ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt subcutaneous fat. Scale bar 50 µm.

We have previously shown that transplantation of subcutaneous adipose tissue does not promote atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice and that mice with subcutaneous fat transplants have lower circulating levels of Mcp-1 compared to mice transplanted with visceral fat 13. Interestingly, ApoE−/− mice that received subcutaneous fat transplants also exhibited reduced leukocyte firm attachment compared to ApoE−/− mice receiving visceral fat transplants (18.6±6.5 vs. 44.1±5.3 adherent cells/mm vessel, p=0.01) (Figure 4). No difference in soluble VCAM-1 22 levels were observed between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving visceral fat (571.0±69.8 vs. 639.7±38.9 ng/ml, respectively, p=NS), or between ApoE−/− mice receiving visceral fat and ApoE−/− mice receiving subcutaneous fat (799.7±63.2 vs. 803.0±26.0 ng/ml, respectively, p=NS). Plasma osteopontin 23–25 levels were not different between ApoE−/− mice receiving visceral fat and ApoE−/− mice receiving subcutaneous fat (29.5±2.3 vs. 30.5±5.6 ng/ml, respectively, p=NS).

Source of circulating Mcp-1

To determine if the transplanted adipose tissue contributed to the plasma levels of Mcp-1 following the fat transplantation procedure, Mcp-1 levels were measured at 4 weeks following transplantation of wild-type visceral fat into ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/− mice. Levels of circulating Mcp-1 increased significantly in ApoE−/− mice receiving Wt fat compared to pre-transplant levels (78.7±11.2 vs. 31.4±2.9 pg/ml, respectively, p<0.01). The plasma Mcp-1 in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt fat was barely detectable (0.1±0.1 pg/ml) 4 weeks after the operation indicating that the donor adipocytes are not the source of elevated Mcp-1 following adipose transplantation.

To determine the contribution of transplanted adipocytes toward local Mcp-1 concentrations, Mcp-1 was also measured from fat homogenates prepared from transplanted Wt adipose tissue collected from ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− and ApoE−/− recipient mice. Mcp-1 levels in fat pads were significantly lower in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice compared to ApoE−/− mice (77.8±28.8 vs. 626.8±187.5 pg/ml, p=0.02) indicating that host cells (e.g. endothelial and leukocytes) infiltrating the fat transplant contribute to the levels of Mcp-1 in adipose tissue.

To determine if adipose tissue Mcp-1 varied with harvest site in this transplant model, Mcp-1 levels were measured in fat homogenates prepared from ApoE−/− mice (n=8) that received subcutaneous fat transplants. Interestingly, Mcp-1 levels were significantly lower in subcutaneous fat transplants compared to visceral fat transplants (246.8±79.7 vs. 626.8±187.5 pg/ml, p=0.04).

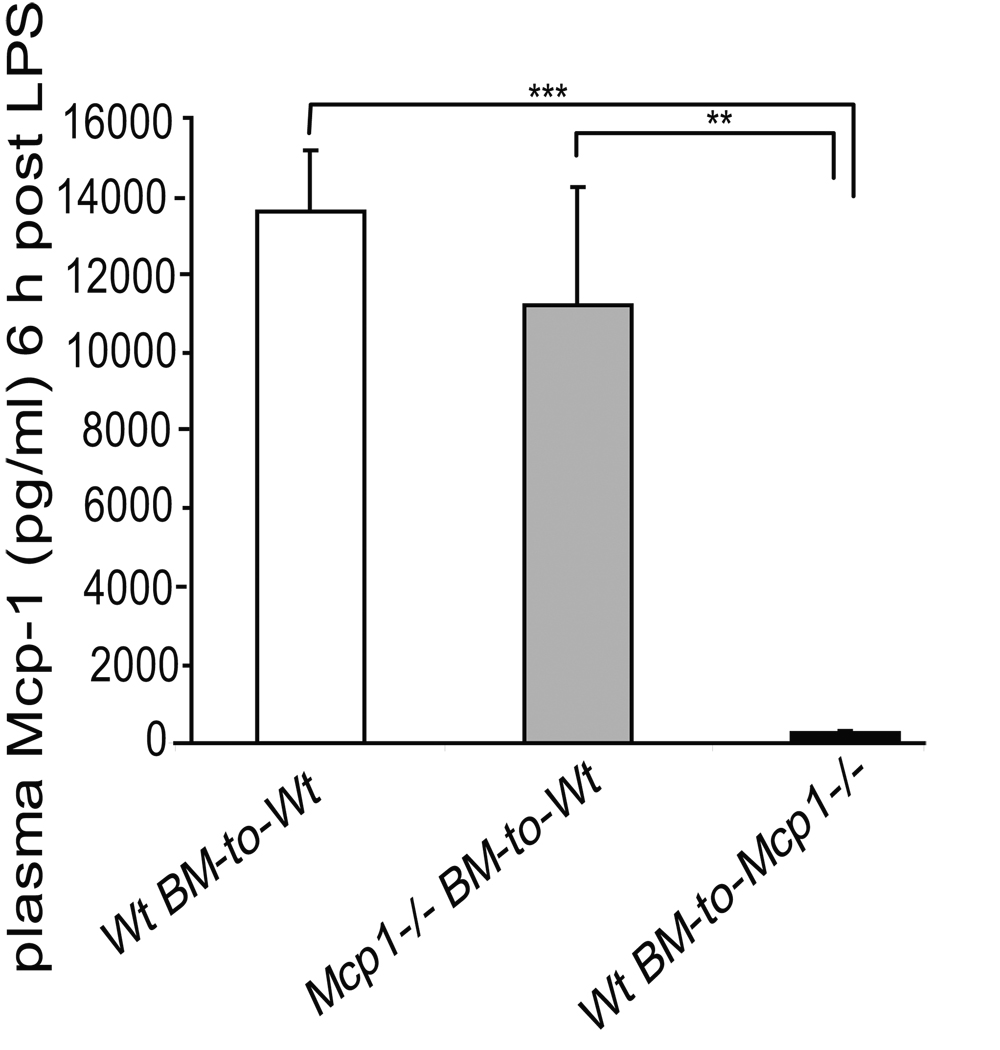

Since the above experiments revealed that the transplanted adipocyte cellular pool was not an important contributor to circulating systemic Mcp-1 levels, bone marrow transplantation (BMT) was used to determine the potential of monocytes/macrophages as a source of circulating Mcp-1. Ten weeks after BMT, plasma Mcp-1 levels were measured in three different BMT groups, Wt mice with Wt marrow (n=9), Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow (n=6) and Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow (n=6). Wt mice with Wt marrow had higher levels of plasma Mcp-1 compared to Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow (94.5±9.2 vs. 66.8±3.2 pg/ml, respectively, p<0.05). The lowest levels of circulating Mcp-1 were measured in Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow (15.6±7.2 pg/ml), compared to the two other groups (p<0.0002 for both comparisons), indicating a greater contributory role of the endothelium towards plasma Mcp-1 levels in the basal state. To investigate whether an acute inflammatory stimulus would change this pattern, BMT mice were given intraperitoneal LPS injection and 6 hours later the circulating Mcp-1 levels were measured (Figure 5). Plasma Mcp-1 increased markedly in Wt mice with Wt marrow and in Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow. However, compared to the other two groups, Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow exhibited a relatively minor increase in circulating Mcp-1 levels (Figure 5). These data indicate that the main source of circulating Mcp-1 is not bone marrow-derived at baseline, or after acute inflammatory stimulus with LPS.

Figure 5.

Plasma Mcp-1 levels in bone-marrow transplanted mice 6 hours after LPS injection. Wt mice with Wt marrow (white bar) and Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow (grey bar) had a significantly higher Mcp-1 levels compared to Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow (black bar). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

We next evaluated the extent to which the host endothelial cells growing into the fat transplants contribute to the Mcp-1 levels in transplanted adipose tissue compared to the monocytes/macrophages infiltrating the fat pads. To determine this, we performed a combination of BMT followed by visceral fat transplantation. Two different BMT groups, Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow (n=4) and Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow (n=8), all received fat transplants from Mcp-1−/− donor mice 4 weeks after BMT. In this experiment, the Mcp-1 in transplanted fat pads could only come from either infiltrating vasculature or infiltrating leukocytes from the host. Six weeks after the fat transplantation, fat pads were removed and Mcp-1 levels were measured from fat homogenates. Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt bone marrow had significantly higher levels of Mcp-1 in their fat pads compared to Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− bone marrow (108±26.5 vs. 6.3±1.9 pg/ml, respectively, p<0.02), indicating that the bone marrow -derived cells were the major source of local Mcp-1 in the transplanted adipose tissue.

We also measured circulating Mcp-1 levels from the mice that received combined BMT and fat transplantation. Mcp-1−/− mice with Wt marrow and Mcp-1−/− fat displayed lower plasma Mcp-1 compared to the Wt mice with Mcp-1−/− marrow and Mcp-1−/− fat (23.6±3.5 vs. 36.2±1.5 pg/ml, respectively, p<0.02). Thus, even though bone-marrow derived cells play a major role in regulating local tissue levels of Mcp-1, the endothelium contributes more to circulating levels of Mcp-1 after both acute inflammatory stimulus (i.e. LPS) and after a more chronic, low grade inflammatory challenge as occurs in the adipose transplantation model.

DISCUSSION

Obesity is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease 3, 26. The mechanisms linking obesity and risk for cardiovascular disease are not completely understood. A recent large study demonstrated that central obesity, which reflects accumulation of visceral adipose tissue, is strongly associated with mortality 27. Excess visceral adiposity has also been shown to be a risk factor for prevalent atherosclerosis 3 and a trigger of markers of inflammation that are strongly associated with complications of atherosclerosis such as myocardial infarction and stroke 28, 29. Thus, visceral adiposity may trigger a systemic inflammatory state which affects the development of atherosclerosis. The specific mediators of vascular risk associated with visceral obesity are unknown, although obese adipose tissue has been shown to express and secrete multiple factors that may promote atherosclerosis 10, 11, 30–32.

To further dissect the specific role of adipose tissue on comorbidities of obesity such as vascular disease, models may be helpful in which confounding variables induced by severe obesity, such as diabetes and extreme hyperlipidemia, do not occur. Surgical implantation of adipose tissue to the dorsal surface of a mouse from a donor of the same background strain leads to a long term viable graft capable of secreting adipose-specific products, such as leptin, at physiological concentrations 13. Transplantation of visceral but not subcutaneous adipose tissue leads to acceleration of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice 13. One of the circulating factors shown to be elevated in the visceral transplant model is Mcp-1 13. However, whether Mcp-1 plays a role in the proatherogenic effect of inflammatory visceral fat is unknown. There are likely multiple steps in the pathway linking visceral fat inflammation and atherosclerosis that could potentially serve as therapeutic targets. For example, adipose tissue inflammation may be initiated by overnutrition causing adipocyte stress, followed by release of factors leading to leukocyte infiltration into adipose tissue 6, 7, 33. A state of monocyte/macrophage activation may then occur leading to release of cytokines and/or activated macrophages which in turn affect the macrovascular endothelium 33, 34. The activated macrovascular endothelium may then lead to further monocyte/macrophage recruitment 35, 36. Thus, there are several steps where Mcp-1 could affect the atherogenic response to inflammatory visceral adipose tissue. The goal of the current study was to determine if Mcp-1 was a mediator of the increased atherosclerosis induced by inflammatory visceral fat.

Mcp-1 is a potential mediator of both adipose tissue inflammation 37, 38 and atherosclerosis 39, 40 based on previous investigations. Mcp-1 deficiency in mice prone to atherosclerosis via deletion of the LDLR receptor, apoE or overexpression of apoB is associated with protection from atherosclerosis when challenged by a high fat diet 39–42. In the setting of obesity, Mcp-1 and its receptor have been shown to contribute to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in some studies 37, 38, 43 while other studies have not demonstrated effects of Mcp-1 on adipose tissue macrophage infiltration 44, 45. Since Mcp-1 may play a role in both adipose tissue inflammation and atherosclerosis, we hypothesized that Mcp-1 may be one of the factors linking inflammatory adipose tissue and atherosclerosis. As several investigators have found increased expression of Mcp-1 in obese adipose tissue stores 6–8, 46, we first tested whether the rise in plasma Mcp-1 observed in our fat transplant model was due to increased production from the inflammatory adipose transplant. To determine this, we performed visceral adipose transplantation from Wt mice to ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice. To our surprise, Mcp-1 was undetectable in the plasma of ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice indicating that in this model, cells of the donor visceral fat transplant are not a major source of circulating Mcp-1. If the adipocyte was a relevant source of circulating Mcp-1, we should have detected it since we have previously shown that plasma levels of leptin are chronically reconstituted in this model when wild-type adipose tissue is transplanted to leptin deficient mice 13. Conversely, transplantation of adipose tissue into ApoE−/− mice produced an increase in circulating Mcp-1 levels. This indicates that either recipient monocytes or the endothelium is producing Mcp-1 in response to a stimulus released from the transplanted adipose tissue. To further differentiate the recipient endothelial cells from the recipient bone marrow-derived pool as a source of circulating Mcp-1, bone marrow transplants were performed between Mcp-1−/− and Wt mice. Mcp-1 levels in Mcp-1−/− mice receiving Wt bone marrow transplants were lower 10 weeks following the transplant while Mcp-1 levels in Wt mice receiving Mcp-1−/− marrow were similar to control Wt mice receiving Wt marrow. A relatively minor bone marrow contribution to circulating Mcp-1 levels was present after LPS administration. Thus, at baseline and in response to an acute inflammatory stimulus, the bone marrow-derived cells are not the major contributor to circulating levels of Mcp-1. However, the bone marrow-derived cells were a relevant source of Mcp-1 content within the transplanted visceral adipose tissue.

Since the circulating systemic Mcp-1 levels are endothelial-derived in the basal state and after acute and chronic inflammatory challenges, we hypothesize that following macrophage infiltration into the transplanted fat there is a systemic increase in adhesive characteristics of the endothelium which could promote atherosclerosis. Consistent with this hypothesis, more leukocyte firm attachment was observed in cremaster venules of ApoE−/− mice with visceral fat transplants compared to ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice with visceral fat transplants. An effect of Mcp-1 on leukocyte firm attachment has been previously observed under flow conditions using in vitro models 35, 47. Interestingly, the reduction in firm attachment in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice was similar to that observed in ApoE−/− mice receiving a subcutaneous fat transplant. The explanation for differences between visceral and subcutaneous fat on vascular disease and circulating Mcp-1 levels remains unclear. We have previously demonstrated that adipocyte-derived factors leptin and adiponectin are not different between ApoE−/− mice receiving visceral and subcutaneous fat transplants 13. Although the factor(s) responsible for triggering endothelial Mcp-1, and the mechanism(s) for differences between subcutaneous and visceral fat are unknown, the current data provide additional evidence that Mcp-1 may be one of the critical mediators of inflammatory visceral fat-induced atherosclerosis, and may contribute to the different vascular effects of visceral and subcutaneous fat.

To provide proof that Mcp-1 plays a contributory role in the proatherogenic effect of visceral inflammatory adipose tissue, visceral fat transplants were performed into ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice maintained on a normal chow diet. Although previous studies indicate that deficiency of Mcp-1 is protective against atherosclerosis in atherosclerotic-prone mice in the absence of fat transplantation, these previous studies were performed with a Western diet challenge that induces extreme hyperlipidimia and accelerates atherosclerosis 39–42. Interestingly, a Western diet triggers macrophage activation and these macrophages then exhibit enhanced adhesive characteristics and contribute to atheroma 48. In the current study, no difference in atherosclerosis was noted between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice on a normal chow diet without adipose transplantation. Following visceral adipose tissue transplantation, the proatherogenic effect of the transplanted fat was observed in ApoE−/− mice but was completely neutralized in ApoE−/−,Mcp-1−/− mice. Thus, the protective effect of Mcp-1 deficiency on atherosclerosis appears to require an inflammatory trigger such as a high fat diet feeding or inflammatory visceral adipose tissue. In the setting of visceral adipose tissue inflammation, Mcp-1 may be a regulator of vasculopathic factors released by inflammatory visceral adipose and/or may mediate the endothelial response of the macrovasculature to atherogenic factors produced by the fat. Although we cannot rule out a differential effect of ApoE release from the donor fat on atherosclerosis, we believe this is unlikely as the ApoE status was the same in all donor fat pads. Interestingly, the Mcp-1 status of the donor adipocytes does not appear to play an important role in regulating macrophage infiltration into fat or in atherosclerotic lesion formation since ApoE−/− mice that received Mcp-1−/− visceral fat displayed equal amount of inflammation in adipose transplants and atherosclerotic burden as ApoE−/− mice transplanted with Wt visceral fat.

In conclusion, recipient Mcp-1 deficiency leads to protection against the proatherogenic effects of inflammatory visceral adipose tissue. Mcp-1 may serve as a therapeutic target in subjects with excessive visceral adiposity at high risk for vascular events.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [HL57346, HL073150 to D.T.E.]

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURES

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith SR, Lovejoy JC, Greenway F, Ryan D, deJonge L, de la Bretonne J, Volafova J, Bray GA. Contributions of total body fat, abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments, and visceral adipose tissue to the metabolic complications of obesity. Metabolism. 2001;50:425–435. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.21693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Regitz-Zagrosek V, Lehmkuhl E, Weickert MO. Gender differences in the metabolic syndrome and their role for cardiovascular disease. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:136–147. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.See R, Abdullah SM, McGuire DK, Khera A, Patel MJ, Lindsey JB, Grundy SM, de Lemos JA. The Association of Differing Measures of Overweight and Obesity With Prevalent Atherosclerosis: The Dallas Heart Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;50:752–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lakka HM, Lakka TA, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. Abdominal obesity is associated with increased risk of acute coronary events in men. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:706–713. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu H, Ghosh S, Perrard XD, Feng L, Garcia GE, Perrard JL, Sweeney JF, Peterson LE, Chan L, Smith CW, Ballantyne CM. T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation. 2007;115:1029–1038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q, Tan G, Yang D, Chou CJ, Sole J, Nichols A, Ross JS, Tartaglia LA, Chen H. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1821–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI19451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1133870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi K, Mizuarai S, Araki H, Mashiko S, Ishihara A, Kanatani A, Itadani H, Kotani H. Adiposity elevates plasma MCP-1 levels leading to the increased CD11b-positive monocytes in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46654–46660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linder K, Arner P, Flores-Morales A, Tollet-Egnell P, Norstedt G. Differentially expressed genes in visceral or subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese men and women. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:148–154. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300256-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazurek T, Zhang L, Zalewski A, Mannion JD, Diehl JT, Arafat H, Sarov-Blat L, O'Brien S, Keiper EA, Johnson AG, Martin J, Goldstein BJ, Shi Y. Human Epicardial Adipose Tissue Is a Source of Inflammatory Mediators. Circulation. 2003;108:2460–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099542.57313.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vohl MC, Sladek R, Robitaille J, Gurd S, Marceau P, Richard D, Hudson TJ, Tchernof A. A survey of genes differentially expressed in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue in men. Obes Res. 2004;12:1217–1222. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohman MK, Shen Y, Obimba CI, Wright AP, Warnock M, Lawrence DA, Eitzman DT. Visceral Adipose Tissue Inflammation Accelerates Atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-Deficient Mice. Circulation. 2008;117:798–805. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J, Jou W, Gavrilova O, Hall KD. Persistent Diet-Induced Obesity in Male C57BL/6 Mice Resulting from Temporary Obesigenic Diets. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodary PF, Westrick RJ, Wickenheiser KJ, Shen Y, Eitzman DT. Effect of leptin on arterial thrombosis following vascular injury in mice. Jama. 2002;287:1706–1709. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olzinski AR, Turner GH, Bernard RE, Karr H, Cornejo CA, Aravindhan K, Hoang B, Ringenberg MA, Qin P, Goodman KB, Willette RN, Macphee CH, Jucker BM, Sehon CA, Gough PJ. Pharmacological Inhibition of C-C Chemokine Receptor 2 Decreases Macrophage Infiltration in the Aortic Root of the Human C-C Chemokine Receptor 2/Apolipoprotein E−/− Mouse: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:253–259. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukhanov S, Higashi Y, Shai S-Y, Vaughn C, Mohler J, Li Y, Song Y-H, Titterington J, Delafontaine P. IGF-1 Reduces Inflammatory Responses, Suppresses Oxidative Stress, and Decreases Atherosclerosis Progression in ApoE-Deficient Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2684–2690. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.156257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho MK, Springer TA. Tissue distribution, structural characterization, and biosynthesis of Mac-3, a macrophage surface glycoprotein exhibiting molecular weight heterogeneity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1983;258:636–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kintscher U, Hartge M, Hess K, Foryst-Ludwig A, Clemenz M, Wabitsch M, Fischer-Posovszky P, Barth TF, Dragun D, Skurk T, Hauner H, Bluher M, Unger T, Wolf AM, Knippschild U, Hombach V, Marx N. T-lymphocyte infiltration in visceral adipose tissue: a primary event in adipose tissue inflammation and the development of obesity-mediated insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1304–1310. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165100. Epub 2008 Apr 1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksson EE, Xie XUN, Werr J, Thoren P, Lindbom L. Direct viewing of atherosclerosis in vivo: plaque invasion by leukocytes is initiated by the endothelial selectins. FASEB J. 2001;15:1149–1157. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0537com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Granger DN, Benoit JN, Suzuki M, Grisham MB. Leukocyte adherence to venular endothelium during ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1989;257:G683–G688. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1989.257.5.G683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galkina E, Ley K. Vascular Adhesion Molecules in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2292–2301. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruemmer D, Collins AR, Noh G, Wang W, Territo M, Arias-Magallona S, Fishbein MC, Blaschke F, Kintscher U, Graf K, Law RE, Hsueh WA. Angiotensin II-accelerated atherosclerosis and aneurysm formation is attenuated in osteopontin-deficient mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:1318–1331. doi: 10.1172/JCI18141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez-Ambrosi J, Catalan V, Ramirez B, Rodriguez A, Colina I, Silva C, Rotellar F, Mugueta C, Gil MJ, Cienfuegos JA, Salvador J, Fruhbeck G. Plasma Osteopontin Levels and Expression in Adipose Tissue Are Increased in Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3719–3727. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nomiyama T, Perez-Tilve D, Ogawa D, Gizard F, Zhao Y, Heywood EB, Jones KL, Kawamori R, Cassis LA, Tschöp MH, Bruemmer D. Osteopontin mediates obesity-induced adipose tissue macrophage infiltration and insulin resistance in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2877–2888. doi: 10.1172/JCI31986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Effect of Weight Loss. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:968–976. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216787.85457.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pischon T, Boeing H, Hoffmann K, Bergmann M, Schulze MB, Overvad K, van der Schouw YT, Spencer E, Moons KGM, Tjonneland A, Halkjaer J, Jensen MK, Stegger J, Clavel-Chapelon F, Boutron-Ruault MC, Chajes V, Linseisen J, Kaaks R, Trichopoulou A, Trichopoulos D, Bamia C, Sieri S, Palli D, Tumino R, Vineis P, Panico S, Peeters PHM, May AM, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, van Duijnhoven FJB, Hallmans G, Weinehall L, Manjer J, Hedblad B, Lund E, Agudo A, Arriola L, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Martinez C, Quiros JR, Key T, Bingham S, Khaw KT, Boffetta P, Jenab M, Ferrari P, Riboli E. General and Abdominal Adiposity and Risk of Death in Europe. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2105–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishikawa J, Tamura Y, Hoshide S, Eguchi K, Ishikawa S, Shimada K, Kario K. Low-Grade Inflammation Is a Risk Factor for Clinical Stroke Events in Addition to Silent Cerebral Infarcts in Japanese Older Hypertensives: The Jichi Medical School ABPM Study, Wave 1. Stroke. 2007;38:911–917. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258115.46765.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, Rifai N. C-Reactive Protein, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Events: An 8-Year Follow-Up of 14 719 Initially Healthy American Women. Circulation. 2003;107:391–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055014.62083.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fain JN, Madan AK. Regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) release by explants of human visceral adipose tissue. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma AM. Adipose tissue: a mediator of cardiovascular risk. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:S5–S7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiao P, Chen Q, Shah S, Du J, Tao B, Tzameli I, Yan W, Xu H. Obesity-Related Upregulation of Monocyte Chemotactic Factors in Adipocytes: Involvement of Nuclear Factor-{kappa}B and c-Jun NH2-Terminal Kinase Pathways. Diabetes. 2009;58:104–115. doi: 10.2337/db07-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Seo K, Yamashita H, Hosoya Y, Ohsugi M, Tobe K, Kadowaki T, Nagai R, Sugiura S. In vivo imaging in mice reveals local cell dynamics and inflammation in obese adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:710–721. doi: 10.1172/JCI33328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maus U, Henning S, Wenschuh H, Mayer K, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. Role of endothelial MCP-1 in monocyte adhesion to inflamed human endothelium under physiological flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H2584–H2591. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saeed RW, Varma S, Peng-Nemeroff T, Sherry B, Balakhaneh D, Huston J, Tracey KJ, Al-Abed Y, Metz CN. Cholinergic stimulation blocks endothelial cell activation and leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1113–1123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K-i, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Miyachi H, Maeda S, Egashira K, Kasuga M. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R, Lemieux J, Slaymaker S, Vaddi K, Charo I, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:115–124. doi: 10.1172/JCI24335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aiello RJ, Bourassa PA, Lindsey S, Weng W, Natoli E, Rollins BJ, Milos PM. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1518–1525. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.6.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu L, Okada Y, Clinton SK, Gerard C, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Rollins BJ. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduces atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Mol Cell. 1998;2:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gosling J, Slaymaker S, Gu L, Tseng S, Zlot CH, Young SG, Rollins BJ, Charo IF. MCP-1 deficiency reduces susceptibility to atherosclerosis in mice that overexpress human apolipoprotein B. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:773–778. doi: 10.1172/JCI5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo J, Van Eck M, Twisk J, Maeda N, Benson GM, Groot PHE, Van Berkel TJC. Transplantation of Monocyte CC-Chemokine Receptor 2-Deficient Bone Marrow Into ApoE3-Leiden Mice Inhibits Atherogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:447–453. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058431.78833.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito A, Suganami T, Yamauchi A, Degawa-Yamauchi M, Tanaka M, Kouyama R, Kobayashi Y, Nitta N, Yasuda K, Hirata Y, Kuziel WA, Takeya M, Kanegasaki S, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y. Role of CC Chemokine Receptor 2 in Bone Marrow Cells in the Recruitment of Macrophages into Obese Adipose Tissue. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35715–35723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inouye KE, Shi H, Howard JK, Daly CH, Lord GM, Rollins BJ, Flier JS. Absence of CC Chemokine Ligand 2 Does Not Limit Obesity-Associated Infiltration of Macrophages Into Adipose Tissue. Diabetes. 2007;56:2242–2250. doi: 10.2337/db07-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirk EA, Sagawa ZK, McDonald TO, O'Brien KD, Heinecke JW. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 Deficiency Fails to Restrain Macrophage Infiltration Into Adipose Tissue. Diabetes. 2008;57:1254–1261. doi: 10.2337/db07-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cancello R, Henegar C, Viguerie N, Taleb S, Poitou C, Rouault C, Coupaye M, Pelloux V, Hugol D, Bouillot J-L, Bouloumie A, Barbatelli G, Cinti S, Svensson P-A, Barsh GS, Zucker J-D, Basdevant A, Langin D, Clement K. Reduction of Macrophage Infiltration and Chemoattractant Gene Expression Changes in White Adipose Tissue of Morbidly Obese Subjects After Surgery-Induced Weight Loss. Diabetes. 2005;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerszten RE, Garcia-Zepeda EA, Lim Y-C, Yoshida M, Ding HA, Gimbrone MA, Luster AD, Luscinskas FW, Rosenzweig A. MCP-1 and IL-8 trigger firm adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium under flow conditions. Nature. 1999;398:718–723. doi: 10.1038/19546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swirski FK, Libby P, Aikawa E, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Ly-6Chi monocytes dominate hypercholesterolemia-associated monocytosis and give rise to macrophages in atheromata. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:195–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI29950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]