Abstract

Codon–anticodon interactions are central to both the initiation and elongation phases of eukaryotic mRNA translation. The obvious difference is that the interaction takes place in the ribosomal A-site during elongation, whereas the 40S ribosomal subunit and associated initiation factors scan the mRNA sequence in search of an initiation codon with Met-tRNAi bound in the P-site, ceasing once codon–anticodon interaction is established at the AUG. As an indirect test of whether the two mechanisms of mRNA sequence inspection are basically similar or not, the effects of six different uridine analog substitutions in the mRNA were examined in reticulocyte lysate translation assays and 80S initiation complex formation assays. Four constructs, each with the same reporter coding sequence, were used, differing in whether the initiation codon was AUG or ACG, and in whether the 5′-UTR had U residues or not. Three analogs (5-bromoU, 5-aminoallylU, and pseudoU) inhibited both elongation and initiation, but the other three had striking differential effects. Ribothymidine had a negligible effect on elongation but caused a ∼50% inhibition of initiation, with little effect on actual AUG recognition, which implies that inhibition must have occurred at some earlier step in initiation. In complete contrast, 2′ deoxyU was prohibitive to elongation but had no effect on initiation, and 4-thioU actually stimulated initiation but quite strongly inhibited elongation processivity. These results show that the detailed mechanisms of inspection of the mRNA sequence during scanning-dependent initiation and elongation must be considerably different.

Keywords: uridine analogs, translation initiation, 40S ribosomal subunit, scanning, elongation

INTRODUCTION

During eukaryotic protein biosynthesis, the nucleotide sequence of the mRNA is inspected at two different stages: (1) during ribosome scanning through the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) and subsequent initiation codon recognition, and (2) during elongation through the open reading frame (ORF). Since codon–anticodon base-pairing interactions are central to both processes, it is widely if tacitly assumed that the ribosome interacts with the mRNA in the same basic way in both cases, although there are obviously differences in detail. During scanning, the 40S ribosomal subunit with Met-tRNAi in the P-site (as an eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNAi ternary complex) migrates along the mRNA until it encounters a cognate AUG triplet complementary to the P-site tRNA anticodon. Although this codon–anticodon interaction is obviously central to initiation, the initiation factors bound to the 40S subunits play a significant role in initiation site selection, which is also influenced by the sequence context of the AUG. Initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A are essential for proper scanning, and affect the conformation of the 40S subunit between an open state, permissive for scanning, and a closed conformation (Maag et al. 2005; Passmore et al. 2007). The establishment of codon–anticodon pairing in a favorable context results in displacement of eIF1 on the 40S subunit, forming the closed conformation and activating the GAP function of eIF5 to promote GTP hydrolysis and phosphate release, which is the final commitment step (Sonenberg and Hinnebusch 2009).

In contrast, during elongation there is a stationary 80S ribosome with an empty A-site into which a succession of eEF1A(EFTu)/GTP/aminoacyl-tRNA ternary complexes bind and subsequently dissociate, until a ternary complex with a cognate tRNA enters the A-site. By analogy with prokaryotic elongation, complementarity of the aminoacyl-tRNA with the mRNA bases results in stabilization of the codon–anticodon interaction by residues in 18S(16S) rRNA, leading to a rotation of the small subunit head known as domain closure (Zhang et al. 2009). In turn this triggers hydrolysis of the GTP (Ogle et al. 2002), with subsequent dissociation of eEF1A(EFTu)/GDP and accommodation of the aminoacyl-tRNA into the large ribosomal subunit A-site. Despite these differences in detail, both initiation via scanning and elongation are processes that primarily depend on codon–anticodon pairing, and therefore the implicit assumption appears to be that the interactions of the small ribosomal subunit with the mRNA are very similar during the modes of scanning-dependent initiation and elongation.

As a test of this assumption, we have investigated the effects of substituting U residues in the mRNA with a variety of modified U's. Although many such substitutions affect both initiation and elongation, surprisingly there are some which show selective effects on just one of these two phases, implying that the interactions of the small ribosomal subunit with the mRNA during initiation by the scanning mechanism are rather different than during elongation. For example, substitution with the 5-methyl derivative, ribothymidine (riboT), had a negligible effect on elongation, yet was surprisingly inhibitory to initiation. At the other extreme 2′ deoxyU substitution was absolutely prohibitive to elongation, yet had no effect on initiation complex formation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Strategy to measure the effects of modified U substitutions on translation

Two assays were used in this work: (1) in vitro translation of full-length capped m7GpppG mRNAs with quantitation of full-length protein product yield, and (2) assay of 80S initiation complex formation using sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Four constructs were used throughout, representing two matched pairs, all of them with the same influenza A virus NS1 coding sequence (693 nucleotides [nt] in length) and 3′-UTR (176 nt). Two of the constructs gave rise to mRNAs with a synthetic 5′-UTR consisting essentially of 19 repeats of the triplet CAA sequence and thus lacking any U residues (Pestova and Kolupaeva 2002; Pöyry et al. 2004), one with an AUG initiation codon (CAA-AUG) and the other an ACG start codon (CAA-ACG) (Fig. 1A). The other two mRNAs had a similar length 5′-UTR consisting of residual polylinker sequences followed by the NS1 5′-UTR sequence, also with either an AUG (NS-AUG) or ACG initiation codon (NS-ACG). The plasmid constructs were linearized either with EcoRI to give full-length mRNA for translation assays, or with HindIII to give a truncated mRNA suitable for 80S initiation complex formation studies (Fig. 1A). Experiments were performed for six different modified U's (Supplemental Fig. 1). Transcription reactions were performed in parallel for standard U and each modified U, by making a master mix with all the components except UTP or UTP analog, dividing into two and supplementing one with UTP and the other with the same concentration of analog. The analogs did not affect the yield of RNA obtained with standard T7 RNA polymerase, except in the case of 4-thioUTP when the yield was ∼65% of the control reaction (with UTP), and 2′ deoxyUTP, which gave essentially zero yield. However, 2′ deoxyUTP was used quite efficiently by the mutant polymerase available under the trade name of T7 R&DNA polymerase (Sousa and Padilla 1995). RNA yield and quality was routinely checked by gel electrophoresis, and several different preparations of substituted RNAs were examined for each analog.

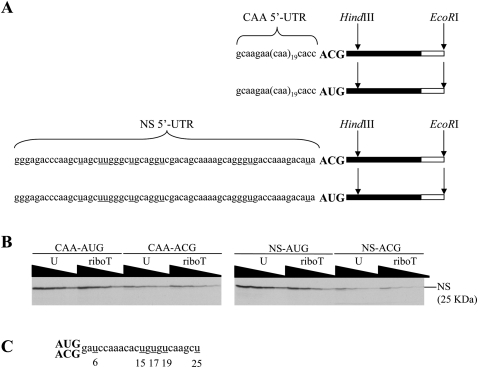

FIGURE 1.

Effects of modified U substitutions on translation. (A) Schematic diagram of the four mRNA species used in translation assays. The two different 5′-UTR sequences are shown with either AUG or ACG start codons. The two possible ORF lengths are indicated, which were created by plasmid linearization with either EcoRI for in vitro translation assays, or with HindIII, for 80S initiation complex formation assays. Filled bars indicate the location of the 693 nt NS ORF within the construct, and the open bars the 176 nt 3′-UTR. U residues in the NS 5′-UTR are underlined. (B) Representative autoradiograph displaying the translation products synthesized from the designated capped mRNAs containing either U or riboT, assayed at 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 μg/mL as indicated by the wedge. (C) Sequence of the 5′ segment of the ORF generated from plasmid linearized with HindIII with the U residues underlined and numbered.

Analog-substituted and control mRNAs were translated over a range of four different RNA concentrations for 30 min, and the products were then separated by gel electrophoresis. The yield of full-length product from analog-substituted mRNA was determined as a percentage of the yield from control mRNA at each RNA concentration, and the mean of these four percentages was taken. A representative example of an autoradiograph with riboT is shown in Figure 1B, and the quantitative results of all substitutions are summarized in Table 1.

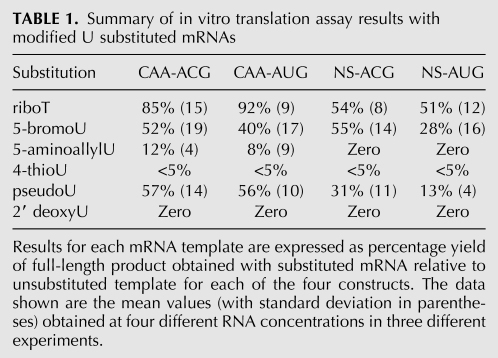

TABLE 1.

Summary of in vitro translation assay results with modified U substituted mRNAs

Effects of substitutions on elongation

The interpretation of the translation assay data starts by examining the CAA-ACG mRNA results. If the substitution caused a reduction in product yield from this template, it was assumed that the analog caused a defect in elongation, as CAA-ACG mRNA contains modified U's only in the ORF and 3′-UTR. Although a ribosome with the initiation codon in the P-site would be in contact with modified U residues at positions +6 and possibly +15, +17, and +19, with respect to the A of the ACG numbered as +1 (Fig. 1C), these residues would be expected to influence elongation rather than initiation per se. By these criteria, riboT substitution had at most only a very marginal effect on elongation, which is probably not significant, but all other analogs were significantly inhibitory. This defective elongation could either be a consequence of elongation proceeding so slowly that many ribosomes failed to reach the termination codon within the 30-min incubation period, or it could be a failure of processivity due to premature ribosome drop-off or stalling. The data do not allow us to distinguish between these two possible explanations, except in those cases where processivity failures occurred at specific sites leading to the synthesis of defined truncated products. However, leaky scanning can also result in the synthesis of defined products shorter than the full-length NS protein (especially when the 5′-proximal initiation codon has been mutated to ACG), and these need to be distinguished from products arising from premature cessation of elongation. Fortunately, the pattern of products resulting from leaky scanning on this NS mRNA has been well documented in an earlier publication and is highly reproducible, with three characteristic bands, previously designated X, Y, and Z (Grünert and Jackson 1994). Product Z is invariably the most abundant (Fig. 2; Grünert and Jackson 1994) and has been shown to be initiated at the first and second in-frame AUG codons (which are separated by only one intervening codon, …AAAAUGACCAUGGCC…) downstream from the AUG (or ACG) initiation site for full-length NS synthesis. The lower abundance X and Y are thought to arise from initiation at a CUG and GUG, respectively, both of which have very good local sequence context, according to the usual criteria (Kozak 1986; Grünert and Jackson 1994). Importantly, no products resulting from leaky scanning were detected that were smaller than Z (Grünert and Jackson 1994).

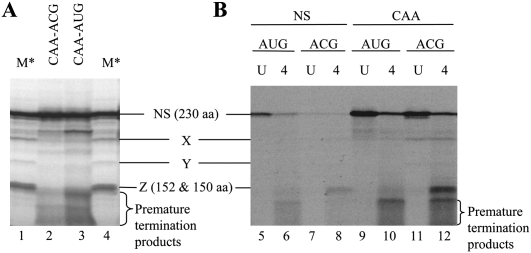

FIGURE 2.

Translation of pseudoU and 4-thioU substituted mRNAs leads to the synthesis of defined truncated protein products. In vitro translation assays were performed (A) with CAA-ACG-pseudoU and CAA-AUG-pseudoU mRNAs, (B) with all four mRNAs either unsubstituted (U) or 4-thioU substituted (4), at 25 μg/mL input mRNA in each case. In B the loading of reactions containing unsubstituted mRNA was one-tenth the standard loading. Lanes denoted M* were loaded with a translation assay of CAA-AUG mRNA supplemented with 0.3 mM EDTA, which gives rise to a high yield of product Z (and lower amounts of X and Y), which are initiated at downstream sites as a result of leaky scanning (Grünert and Jackson 1994).

PseudoU substitution resulted in a smear of short products smaller than Z, which do not correspond to products generated by leaky scanning (Fig. 2A), and thus have the characteristics expected of premature cessation of elongation, either through ribosome stalling or ribosome drop-off. The absence of products resulting from leaky scanning, even when the 5′-proximal initiation codon is ACG, is hardly surprising, because, as we show later, pseudoU substitution is highly inhibitory to initiation on mRNAs with such substitutions in the 5′-UTR, and although the 5′-UTR proper of the CAA-ACG mRNA lacks U residues, the first ∼240 nt of coding region become, in effect, part of the 5′-UTR for any ribosomes that initiate at the Z-site by leaky scanning.

On the other hand, truncated products resulting from leaky scanning were observed in the case of 4-thioU substitution (Fig. 2B). Indeed the yield of Z even exceeded the yield of full-length NS protein when the latter was driven by an ACG initiation codon, suggesting the possibility that 4-thioU substitution is not just permissive to leaky scanning and downstream initiation, but may even be stimulatory, as was also seen in the initiation complex formation assays described later. Translation of the 4-thioU substituted RNA also gave a distinct band of ∼16 kDa, smaller than Z but larger than the (unlabeled) globin, and a smear of even smaller products (Fig. 2B), a pattern which was similar to that seen with pseudoU substituted mRNA and is likewise attributed to defective processivity of elongation. Thus, pseudoU and 4-thioU substitution are similar in that they both cause premature cessation of elongation, but they differ in that only 4-thioU is permissive (and possibly even stimulatory) for leaky scanning and initiation at far downstream sites.

In the case of 2′ deoxyU substitution no full-length or truncated products were detected. Even when the reactions were supplemented with a range of G418 concentrations no products were visible on the gel (data not shown), though it should be noted that the gel electrophoresis method of product analysis would not have revealed very short oligopeptides of less than ∼50 residues. These results with 2′ deoxyU substituted mRNAs make sense in the light of previous work. In prokaryotic systems, DNA templates have been shown to direct the synthesis of short peptides in the presence of neomycin (McCarthy and Holland 1965) and very short products in the absence of the drug (Potapov et al. 1988). With RNA templates, binding of cognate aminoacyl-tRNA to the A-site is stabilized by hydrogen-bonding of 30S ribosomal subunit residues A1491, A1492, and G530 to the 2′-OH groups of the non-wobble positions of the codon and anticodon, which leads to domain closure and hydrolysis of the EFTu-associated GTP (Ogle et al. 2002). The inability to maximize this hydrogen-bonding in the case of a DNA template presumably results in rather weak A-site binding even of a cognate aminoacyl-RNA, and hence elongation is exceedingly inefficient (Potapov et al. 1995). Our results imply that the lack of 2′-OH groups on just the U residues is enough to recapitulate the effects seen with DNA templates.

Effects of substitutions on initiation assessed by in vitro translation assays

In principle, if a particular analog has a greater negative effect on mRNAs with the NS 5′-UTR than the CAA 5′-UTR, this would be interpreted as evidence that its substitution in the 5′-UTR causes inhibition of initiation. However, because this translation assay depends on the synthesis of full-length NS protein, no conclusions regarding initiation can be drawn for those analogs, which caused an extremely severe inhibition of elongation, namely 4-thioU, 2′ deoxyU, and 5-aminoallylU. This is an unavoidable problem inherent in the nature of the assay where the read-out is the yield of full-length NS product. To circumvent this problem, we therefore studied initiation more directly by using sucrose density gradient centrifugation to assay the formation of 80S initiation complexes on NS-ACG and NS-AUG mRNAs under conditions where elongation is blocked by the addition of anisomycin, as described in the following section.

Nevertheless, within these inherent limitations the translation assay data in Table 1 indicate that 5-bromoU and pseudoU substitution, which both caused a rather modest (∼50%) inhibition of elongation on the CAA-ACG mRNA, also inhibited the initiation step, because the substitution caused a significantly greater reduction of the yield of full-length NS protein product with the NS-AUG mRNA than the CAA-ACG template. However, the complication of negative effects of the substitutions on both the initiation and elongation phases of mRNA translation precludes any reliable quantitative estimate of the inhibition of initiation per se, although it seems reasonable to conclude from the results with the NS-AUG mRNA (Table 1) that initiation is more sensitive to pseudoU than to 5-bromoU substitution, which was in fact confirmed in the initiation complex formation assays described below.

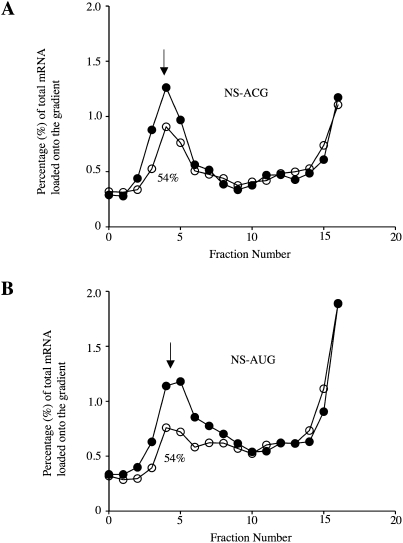

The only clear-cut conclusion regarding initiation that could be drawn from the translation assay data concerns riboT substitution, which had a negligible effect on elongation on the mRNAs with the CAA-repeat 5′-UTR, yet reduced translation of the mRNAs with the NS 5′-UTR by ∼50% (Table 1), implying that the substitution inhibited initiation by ∼50%, although without any selective effect on initiation codon recognition, as shown by the fact that the magnitude of the inhibition with NS-ACG and NS-AUG mRNAs was the same. These conclusions are entirely consistent with the results of initiation complex formation assays with riboT-substituted mRNAs presented in the following section.

Initiation complex formation assays

For these assays we used reticulocyte lysates which had not been treated with micrococcal nuclease, because in our experience these give simpler kinetics of 80S complex formation, with a rapid burst phase followed by very little subsequent increase in the yield of such complexes (Darnbrough et al. 1973). In contrast, in our experience nuclease-treated lysate gives distinctly bi-phasic kinetics of 80S complex formation, in which the initial burst is followed by a quite significant steady increase. The explanation may lie in the fact that nuclease-treatment leaves the active ribosomes stranded on fragments of globin mRNA, and although some of these may run off during the nuclease-treatment step, peptidyl-tRNA release from such ribosomes seems relatively slow, and limits the rate at which these ribosomes become available for further translation. The downside of using untreated lysate is that there are relatively few ribosomes available for initiation complex formation, and thus the yield of such complexes is inevitably low, but we find that the simpler “burst” kinetics in these circumstances outweighs this disadvantage.

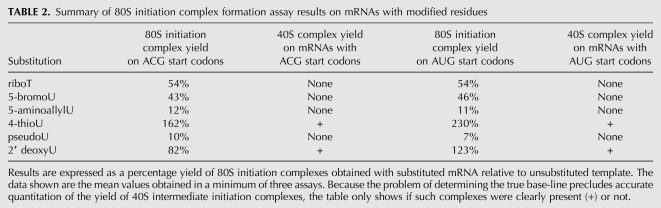

In these experiments, assays on each substituted mRNA and the corresponding control were each carried out in triplicate, with the results from all three sucrose gradients averaged (but error bars have been omitted for clarity), and the 80S initiation complex yield obtained with the substituted mRNA was expressed as a percentage of the control mRNA yield. Results with riboT substituted mRNA are shown in Figure 3, and the quantitative results with all substituted mRNAs are summarized in Table 2. These data show that pseudoU and all analogs with substituents in the 5-position of the pyrimidine ring resulted in inhibition of initiation complex formation (Table 2), with pseudoU and 5-aminoallylU each having a more significant negative effect than riboT (Fig. 3) or 5-bromoU. Given that riboT and 5-bromo substitutions are similar in size (van der Waals volumes of 24.53 and 26.52 Å3, respectively), but very different in electronegativity, while the 5-aminoallyl substitution is bulkier than either of them (67.49 Å3) (Zhao et al. 2003), it would appear that the negative effect on initiation is determined more by the bulk of the substitution at the 5-position rather than by its electronegativity.

FIGURE 3.

Initiation complex formation assays with U and riboT containing mRNAs. The 32P-labeled mRNA profiles across the sucrose gradients, averaged over three independent experiments, are displayed as a percentage of the total mRNA loaded onto the gradient for (○) riboT substituted and (●) unsubstituted (A) NS-ACG mRNA and (B) NS-AUG mRNA. 80S initiation complex peaks are marked with arrows. The relative yield of 80S initiation complexes observed with the modified mRNA is expressed as a percentage of that found with the corresponding unmodified mRNA.

TABLE 2.

Summary of 80S initiation complex formation assay results on mRNAs with modified residues

The process of initiation can be considered as having three stages: loading of the 43S pre-initiation complex (a 40S ribosomal subunit with associated initiation factors including an eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNAi ternary complex) on the 5′-UTR, followed by linear scanning of the 5′-UTR, and, finally, recognition of the initiation codon and commitment to initiate at that site. The data of Table 2 show that none of these inhibitory substitutions had a significant effect on the last step, because the same outcome was observed irrespective of whether the initiation codon was AUG or ACG. However, the data do not allow us to distinguish whether the inhibition of initiation complex formation caused by substitutions in the NS 5′-UTR is due to defective 43S complex loading, or to some defect in scanning such as premature drop-off. In principle it might be possible to distinguish between these two explanations by comparing a 5′-UTR consisting purely of CAA-repeats with one in which just the 5′-proximal portion consists of such repeats and the rest is heteropolymeric (i.e., includes U residues). However, the transition from 43S loading to scanning is rather a vague concept, and we do not know the precise position of the 43S complex on the mRNA at the time when this transition occurs. Thus, on present knowledge, it is not clear how long the 5′-proximal CAA-repeat portion would need to be for the results of such an experiment to show conclusively and definitively whether the defect is in scanning per se, rather than 43S complex loading.

However, it is worth recalling that no synthesis of Z as a result of leaky scanning was seen with pseudoU substituted CAA-ACG mRNA (Fig. 2A, lane 2), where the 5′-proximal 66 nt lack any substituted U residues. Thus it is reasonable to conclude that in this case there would have been no inhibition of 43S complex loading, and that the lack of leaky scanning to the Z initiation site was therefore most likely to be due to either derailment or stalling of the scanning 43S ribosome as it migrated through the 5′-proximal ∼240 nt of the NS ORF, which had numerous pseudoU substitutions.

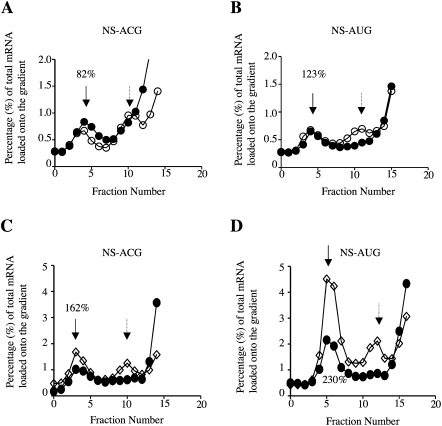

None of the modifications at the 5-position caused the accumulation of detectable 43S/mRNA complexes, which would be indicative of stalling during scanning (Table 2). However, we do not know whether such stalled 40S ribosomal subunits would remain mRNA-associated during the sucrose gradient centrifugation step. Although complexes of 40S subunits associated with mRNA at sites other than the initiation codon have been detected by sucrose gradient centrifugation of wheat germ extracts (Kozak and Shatkin 1978; Kozak 1979), this required special conditions such as a reduced Mg2+ concentration, or the presence of edeine, and it remains unclear whether such complexes formed under more standard conditions would be stable to sucrose gradient centrifugation. Complexes of 40S subunits associated with mRNA were seen with 2′ deoxyU and 4-thioU substitution (Fig. 4; Table 2, 40S complex yield with ACG and AUG start codons), but this could conceivably be a peculiarity of these particular substitutions, and it does not necessarily testify to the stability of a stalled scanning 40S subunit on 5′-UTRs with other substitutions.

FIGURE 4.

Initiation complex formation assays with (A,B) 2′ deoxyU substituted mRNA and (C,D) 4-thioU substituted mRNA. The 32P-labeled mRNA profiles across the sucrose gradients, averaged over three independent experiments, are displayed as a percentage of the total mRNA loaded onto the gradient for (○) 2′ deoxyU substituted, (◇) 4-thioU substituted, and (●) unsubstituted (A,C) NS-ACG mRNA-and (B,D) NS-AUG mRNA. 80S initiation complex peaks are marked with solid arrows and 40S intermediate initiation complex peaks with dashed arrows. The relative yield of 80S initiation complexes observed with the modified mRNA is expressed as a percentage of that found with the corresponding unmodified mRNA.

Surprisingly, 2′ deoxyU substitution, which was completely prohibitive to elongation, resulted in only a modest (and possibly not significant) reduction of initiation complex formation at an ACG codon (Fig. 4A), and actually stimulated complex formation slightly at an AUG start codon (Fig. 4B). Qualitatively similar, but quantitatively more extreme results were seen in the case of 4-thioU substitution: an increase in initiation complex formation at an ACG (Fig. 4C), and a reproducibly even larger increase at an AUG (Fig. 4D). Though surprising, this observation is in fact entirely consistent with the results of the translation assays, where an unexpectedly high yield of product Z was seen with mRNAs that had an ACG 5′-proximal start codon (Fig. 2B, lane 12), indicating that 40S subunits were fully capable of (leaky) scanning on the 4-thioU substituted mRNA for a distance of ∼300 nt followed by initiation at As4UG codons at this downstream position.

As substitution with 4-thioU had a stimulatory effect on initiation complex formation on NS-ACG mRNA (Fig. 4C) and an even stronger stimulation with NS-AUG mRNA (Fig. 4D), it seems that this substitution not only stimulates 40S subunit loading onto the mRNA or actual scanning processivity but that initiation complex formation is more efficient at an As4UG codon than at an unsubstituted AUG. The difference is unlikely to be due to more leaky scanning past an unsubstituted AUG than an As4UG initiation codon, because the context of this NS initiation codon is very favorable (Kozak 1986; Grünert and Jackson 1994), which explains why initiation can occur quite efficiently even with non-AUG codons at this position (Fig. 2B, lane 11). Moreover, the products X, Y, and Z, characteristic of leaky scanning on this NS1 mRNA, were not seen when the initiation codon was (unsubstituted) AUG (Fig. 2B, lanes 5,9). Another conceivable explanation, which can probably be rejected, is that the inhibition of elongation by anisomycin was incomplete, allowing some 80S ribosomes to run off the short mRNAs used for initiation complex formation assays. However, the concentration of anisomycin used was >20-fold higher than the concentration required for complete inhibition of amino acid incorporation into acid-precipitable protein, and the incubation time was restricted to just 5 min.

The regulation of 15-lipoxygenase mRNA translation initiation in erythroid cells suggests a possible explanation for why initiation at an unsubstituted AUG might be less efficient than at an As4UG. The binding of hnRNP E1 and hnRNP K to a 3′-UTR motif in this mRNA results in inhibition of its translation specifically at the initiation step (Ostareck et al. 2001). What is especially significant in this case is that very strong inhibition of formation of 80S initiation complexes (in the presence of GTP) was observed, yet there was no inhibition of 40S/mRNA initiation complexes formed in the presence of GMPPNP. Assuming that the GMPPNP is acting solely as a non-hydrolysable analog of GTP and is not promoting events that do not occur at all when GTP is used, the implication is that the step at which the 40S/mRNA complex with a bound eIF2/GTP/Met-tRNAi ternary complex is converted to an 80S/mRNA/Met-tRNAi initiation complex plus eIF2/GDP is largely abortive, with nearly all such 40S complexes proceeding along some sort of discard pathway. Given that this putative discard pathway appears to be so overwhelmingly predominant under these special circumstances, it seems quite possible that it might also operate to a certain extent under standard conditions, and if the discard was less effective at an As4UG codon than at an AUG, this could explain why 80S initiation complex formation is more efficient at the analog-substituted start codon than at an AUG.

Although this work has left some issues partly unresolved, such as whether inhibitory substitutions in the 5′-UTR affect the initial loading of 40S subunits on to the mRNA or the actual 40S subunit scanning (or both), the important conclusion to emerge is that the nature of the interaction between the mRNA and the 40S ribosomal subunit (or, strictly, the 40S subunit plus associated initiation factors) during initiation must be very different from the ribosome–mRNA interaction during elongation. This is shown unambiguously by the diametrically opposite effects of riboT and 2′ deoxyU substitution (Tables 1, 2). The former has a negligible effect on elongation, yet inhibits initiation efficiency by ∼50% in both the translation assay and the initiation complex formation assay. Considering that the 61 nt NS 5′-UTR has only seven U residues, five of them (including the only ..UU.. dinucleotide motif) in the 5′-half of the UTR and only two in the 3′-half, this sensitivity of initiation to riboT substitution seems quite remarkable, especially given the very small negative effect of the substitution on elongation (Table 1). In contrast, 2′ deoxyU substitution is extremely inhibitory to elongation, as expected, yet surprisingly has no apparent effect on initiation. In a similar vein, 4-thioU substitution is inhibitory to the processivity of elongation over long distances, yet actually stimulates initiation complex formation.

Further mechanistic insights into the reasons for this difference are beyond the capabilities of current technology, and new approaches will be required, possibly single particle methods for studying ribosome scanning. Nevertheless, our results have flagged up an interesting problem that would warrant further investigation once such new methods have been developed, and they have identified which analogs would be especially worth examining.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parallel transcription reactions

A master mix of 10 μg linearized DNA, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM CTP, 0.1 mM GTP, 2.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM m7GpppG cap analog, 32.6 U RNA guard, T7 RNA polymerase, trace [α-32P]CTP, or trace [α-32P]ATP was prepared and then divided into two reactions. UTP was added to one and modified UTP to the other, to give final concentrations of 1 mM in each case. These transcription reactions were incubated for 20 min at 37°C and then chased with GTP for 30 min by raising its concentration to 1 mM. Standard T7 polymerase was unable to incorporate 2′ deoxyU, so mutant T7 R&DNA polymerase was used in its place (Sousa and Padilla 1995); 200 U T7 R&DNA was required for 100 μL transcription reactions. The extent of 32P incorporation into RNA was determined by scintillation counting. Measuring the total 32P present in the transcription and the 32P present in purified RNA allowed the calculation of the RNA concentration.

In vitro translation assays

Standard translation assays were carried out at room temperature (26°C) for 30 min using 70% (v/v) nuclease-treated rabbit reticulocyte lysate with the following additions (final concentrations): 0.5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 0.1 mM amino acids (all except methionine), 0.0185 MBq/μL [35S]methionine. An equal volume of RNase stop was added to each translation assay, and further incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Samples were diluted fivefold with 1× Protein Sample Buffer/βME and heated at 90°C for 2 min. mRNA titrations were carried out as serial dilutions, e.g., 50, 25, 12.5, and 6.25 μg/mL. Translation assay samples were loaded onto 20% polyacrylamide gels and run at 25–55 mA for 2–4 h, in 1× SDS buffer. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue R 250, destained, and dried onto blotting paper at 80°C under vacuum and exposed to X-ray film. This film was later developed and the translation product bands were quantified by densitometry using Phoretix 1D advanced and Phoretix PowerScan programs.

Sucrose gradient sedimentation

The initiation complex assay reactions were the same as for translation assays except that the reticulocyte lysate was not pre-treated with nuclease, and unlabeled methionine replaced the radiolabeled Met. They were pre-incubated at 30°C for 5 min, after which anisomycin was added (100 μM final). After another 5 min at 30°C, reactions were programmed with 32P-labeled mRNA at a concentration between 5 and 10 μg/mL. Incubations were then continued for five more minutes at 30°C. Reactions were diluted fivefold with ice-cold buffer (25 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1.1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 0.25 mM DTT) and put on ice. Samples were loaded onto 4 mL 15%–40% linear sucrose gradients, made in the same buffer. These gradients were then subjected to ultra-centrifugation in a Beckman SW60 rotor at 50,000 rpm (256,760gav) for 105 min with the brake off. Gradients were pumped out using a peristaltic pump coupled to a capillary tube that was gently lowered almost to the very bottom of the tube. Gradients were pumped through the flow cell of a UV monitor (254 nm) to a fraction collector, which was set to collect 220 μL fractions. The amount of mRNA in each fraction was determined by measuring Cerenkov radiation.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tuija Pöyry, Deirdre Scadden, and Chris Smith for helpful discussions; and Rosemary Farrell and Jenny Reed for technical support. This work was funded by a Wellcome Trust Programme Grant (062348), and J.L.A. held a Medical Research Council studentship. The experiments were conceived by J.L.A. and R.J.J. then performed by J.L.A. The manuscript was prepared by J.L.A and R.J.J.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.1978610.

REFERENCES

- Darnbrough C, Legon S, Hunt T, Jackson RJ 1973. Initiation of protein synthesis: Evidence for messenger RNA-independent binding of methionyl-transfer RNA to the 40 S ribosomal subunit. J Mol Biol 76: 379–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünert S, Jackson RJ 1994. The immediate downstream codon strongly influences the efficiency of utilization of eukaryotic translation initiation codons. EMBO J 13: 3618–3630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M 1979. Migration of 40 S ribosomal subunits on messenger RNA when initiation is perturbed by lowering magnesium or adding drugs. J Biol Chem 254: 4731–4738 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M 1986. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 44: 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak M, Shatkin AJ 1978. Migration of 40 S ribosomal subunits on messenger RNA in the presence of edeine. J Biol Chem 253: 6568–6577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag D, Fekete CA, Gryczynski Z, Lorsch JR 2005. A conformational change in the eukaryotic translation preinitiation complex and release of eIF1 signal recognition of the start codon. Mol Cell 17: 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy BJ, Holland JJ 1965. Denatured DNA as a direct template for in vitro protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 54: 880–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle JM, Murphy FV, Tarry MJ, Ramakrishnan V 2002. Selection of tRNA by the ribosome requires a transition from an open to a closed form. Cell 111: 721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostareck DH, Ostareck-Lederer A, Shatsky IN, Hentze MW 2001. Lipoxygenase mRNA silencing in erythroid differentiation: The 3′UTR regulatory complex controls 60S ribosomal subunit joining. Cell 104: 281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore LA, Schmeing TM, Maag D, Applefield DJ, Acker MG, Algire MA, Lorsch JR, Ramakrishnan V 2007. The eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A induce an open conformation of the 40S ribosome. Mol Cell 26: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestova TV, Kolupaeva VG 2002. The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev 16: 2906–2922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potapov AP, Soldatkin KA, Soldatkin AP, El'skaya AV 1988. The role of a template sugar-phosphate backbone in the ribosomal decoding mechanism. Comparative study of poly(U) and poly(dT) template activity. J Mol Biol 203: 885–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potapov AP, Triana-Alonso FJ, Nierhaus KH 1995. Ribosomal decoding processes at codons in the A or P sites depend differently on 2′-OH groups. J Biol Chem 270: 17680–17684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöyry TA, Kaminski A, Jackson RJ 2004. What determines whether mammalian ribosomes resume scanning after translation of a short upstream open reading frame? Genes Dev 18: 62–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG 2009. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: Mechanisms and biological targets. Cell 136: 731–745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa R, Padilla R 1995. A mutant T7 RNA polymerase as a DNA polymerase. EMBO J 14: 4609–4621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Dunkle JA, Cate JH 2009. Structures of the ribosome in intermediate states of ratcheting. Science 325: 1014–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YH, Abraham MH, Zissimos AM 2003. Fast calculation of van der Waals volume as a sum of atomic and bond contributions and its application to drug compounds. J Org Chem 68: 7368–7373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]