Abstract

PUF (Pumilio and FBF) proteins provide a paradigm for mRNA regulatory proteins. They interact with specific sequences in the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs and cause changes in RNA stability or translational activity. Here we describe an in vitro translation assay that reconstitutes the translational repression activity of canonical PUF proteins. In this system, recombinant PUF proteins were added to yeast cell lysates to repress reporter mRNAs bearing the 3′UTRs of specific target mRNAs. PUF proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans were active in the assay and were specific by multiple criteria. Puf5p, a yeast PUF protein, repressed translation of four target RNAs. Repression mediated by the HO 3′UTR was particularly efficient, due to a specific sequence in that 3′UTR. The sequence lies downstream from the PUF binding site and does not affect PUF protein binding. PUF-mediated repression was sensitive to the distance between the ORF and the regulatory elements in the 3′UTR: excessive distance decreased repression activity. Our data demonstrate that PUF proteins function in vitro across species, that different mRNA targets are regulated differentially, and that specific ancillary sequences distinguish one yeast mRNA target from another. We suggest a model in which PUF proteins can control translation termination or elongation.

Keywords: translational control, PUF protein, RNA-binding protein, mRNA control

INTRODUCTION

The lives of mRNAs are regulated from birth to death. In the cytoplasm, their activity depends on proteins and RNAs that control mRNA localization, translation, and decay. The 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNA recruits these factors and thereby determines the mRNA's fate (Kuersten and Goodwin 2003). Understanding how 3′-UTR-borne complexes exert their effects is an important challenge.

PUF proteins (Pumilio and FBF) are a paradigm for protein-mediated control of mRNA fate. PUF proteins are required for stem cell self-renewal in a variety of species and cell types (Wickens et al. 2002). PUFs also have acquired idiosyncratic functions, including roles in body patterning in Drosophila, mating-type switching and mitochondrial activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and cell fate determination in Caenorhabditis elegans (Wickens et al. 2002; Wharton and Aggarwal 2006). As judged by RNP immunopurification and microarray (“RIP-chip”) analysis, each PUF protein interacts with a large group of mRNAs, ranging from tens to thousands in yeast, Drosophila, and human cells (Gerber et al. 2004, 2006; Galgano et al. 2008). To date, all PUF proteins bind specific sequences in the 3′ UTR, termed the PBE, or PUF binding element (Wickens et al. 2002). Canonical PBEs contain a “UGUN3-5AU” motif (“N” is any nucleotide), although variations exist (Wang et al. 2002, 2009; Gerber et al. 2004; Miller et al. 2008; Koh et al. 2009). PUF proteins usually repress the mRNAs they bind, although several recent reports demonstrate activation as well (Pique et al. 2008; Kaye et al. 2009; Suh et al. 2009).

PUF proteins decrease the amount of protein produced either by repressing translation or enhancing mRNA decay (Wickens et al. 2002). mRNA destabilization often is correlated with deadenylation of the target mRNA (Chagnovich and Lehmann 2001; Wickens et al. 2002; Goldstrohm et al. 2007). PUF proteins directly bind Pop2p, which recruits the Ccr4/Pop2/Not deadenylase complex (Goldstrohm et al. 2006; Kadyrova et al. 2007). Ccr4p is the major cytoplasmic deadenylase in yeast (Collart 2003; Denis and Chen 2003; Goldstrohm et al. 2006, 2007). PUFs may also enhance decay through Pop2p's indirect recruitment of Dhh1p or Dcp1p, both of which enhance decapping (Hata et al. 1998; Coller et al. 2001; Maillet and Collart 2002). Recruitment of the Ccr4p/Pop2/Not complex may mediate translational repression as well (Goldstrohm et al. 2006). Indeed, Dhh1p can repress translation (Coller et al. 2001; Minshall et al. 2001). PUF proteins also can act by sequestration of the m7GpppG cap that is required for translation of most mRNAs. For example, the Drosophila PUF protein, Pumilio, recruits Brat, which, in turn, binds d4EHP. The latter protein binds the cap and so inhibits translation (Wickens et al. 2002; Cho et al. 2006).

PUF repression complexes vary for different transcripts even in the same organism. In Drosophila, repression of the cyclin B mRNA requires only Pumilio and Nanos, whereas repression of hunchback requires a complex of Pumilio, Nanos, and Brat (Sonoda and Wharton 2001). The outcome of PUF regulation is also developmentally controlled: In the C. elegans germline, FBF first represses and later activates the gld-1 mRNA (Suh et al. 2009). Thus, a single PUF protein can act through multiple mechanisms and binds multiple protein partners.

S. cerevisiae possesses five canonical PUF proteins: Puf1p/Jsn1p, Puf2p, Puf3p, Puf4p, and Puf5p/Mpt5p. mRNAs that associate with all five yeast PUF proteins have been identified by “RIP-chip” (Gerber et al. 2004). Here, we chose to analyze mRNAs that not only interacted with Puf5p, but whose mRNA stability and/or translation were affected in vivo by Puf5p. HO, CIN8, and RAX2 mRNAs met these criteria (Gerber et al. 2006; Seay et al. 2006; Hook et al. 2007). Our aim was to establish a set of targets whose regulation was recapitulated in vitro, enabling us to uncover mRNA-specific variations in regulation and dissect their mechanisms.

PUF-mediated control of HO mRNA is particularly well documented. HOp is the endonuclease responsible for mating type switching, a key event in yeast biology. Not surprisingly, HOp expression is regulated at multiple levels (Nasmyth 1993; Broach 2004; Cosma 2004; Klar 2007). HO mRNA is a target of both Puf4p and Puf5p, which mediate repression by interacting with distinct sequences in the HO 3′UTR (Goldstrohm et al. 2006, 2007; Hook et al. 2007). Repression by Puf5p decreases mating-type switching specifically in daughter cells (Tadauchi et al. 2001).

CIN8, RAX2, and DHH1 were initially identified as candidate Puf5p targets in a RIP-chip experiment and later in a yeast three-hybrid screen for RNA sequences that interact with Puf5p (Gerber et al. 2004; Seay et al. 2006). Cin8p is a kinesin-related motor protein involved in spindle assembly during mitosis (Gardner et al. 2008; Fridman et al. 2009). The CIN8 3′UTR binds to Puf5p with high affinity (∼50 nM), and its half-life nearly doubles in the absence of Puf5p (Seay et al. 2006). Rax2p is a membrane protein involved in axial polarity; its mRNA is repressed and destabilized by Puf5p (Seay et al. 2006). Dhh1p is an RNA helicase that associates with the Ccr4/Not complex (Maillet and Collart 2002); DHH1 mRNA interacts with Puf5p (Seay et al. 2006).

In vitro systems have been instrumental in deciphering mechanisms of translational control (Gebauer and Hentze 2007; Mathews et al. 2007 and references therein; Wu et al. 2007). To analyze PUF-mediated repression in S. cerevisiae, we developed an assay in which recombinant, canonical PUF proteins repressed translation in a yeast cell extract. Using that assay, we analyzed key features of the mRNA that are required for repression and uncovered differences in repression of different target mRNAs.

RESULTS

PUF repression recapitulated in vitro

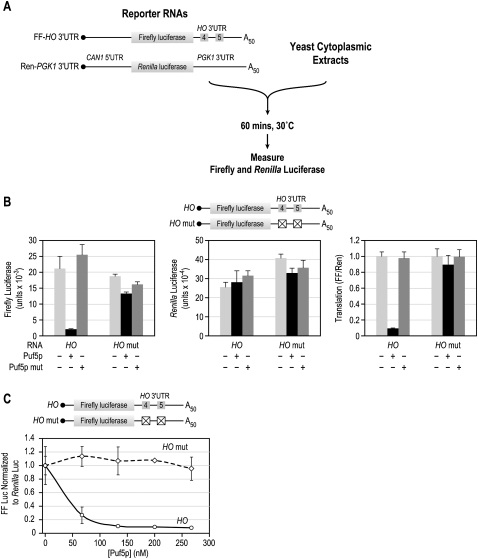

To better understand the function of PUF proteins, we used a cell-free system that supports PUF-mediated repression. Purified recombinant PUF proteins were combined with reporter mRNAs and a crude yeast extract that supports translation in vitro (Fig. 1A; Iizuka and Sarnow 1997; Wu et al. 2007). The purity and integrity of all purified proteins were verified by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis (Supplemental Fig. 1). To test Puf5p-specific repression, we used a luciferase reporter with the firefly luciferase open reading frame (ORF) and the 3′UTR from HO mRNA. A Renilla luciferase reporter lacking PUF binding sites was included in every reaction as an internal control (Fig. 1A). Recombinant Puf5p repressed the HO reporter 10-fold, but had no effect on the control reporter (Fig. 1B). Repression was specific by two criteria: A mutant reporter that lacked PUF binding sites, HO mut, was unaffected by Puf5p; and a mutant Puf5p incapable of binding RNA was unable to repress (Fig. 1B). The GST tag used to purify the proteins did not affect protein activity as 6xHis-tagged Puf5p behaved identically (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Puf5p represses translation in vitro. (A) The in vitro translation assay. Yeast cytoplasmic extracts and two luciferase reporter RNAs were combined with reaction buffers and allowed to translate for 1 h at 30°C. Each reaction contained two luciferase reporters: The HO reporter consisted of a short 5′UTR, the firefly luciferase ORF, and the HO 3′UTR. The boxes in the diagram labeled 4 and 5 represent the binding sites of Puf4p and Puf5p, respectively. The control reporter was composed of the 5′UTR of CAN1, the Renilla luciferase ORF, and the 3′UTR from PGK1. All reporters carried a m7GpppG cap structure and a 50-nt poly(A) tail. After incubation, levels of firefly and Renilla luciferase were determined using a luminescence-based detection system. (B) Puf5p specifically represses the HO reporter. The first graph shows the firefly (FF) luciferase response, the second graph shows the control Renilla (Ren) luciferase response, and the last graph shows normalized responses (FF/Ren). Normalization consists of dividing the firefly by the Renilla response and setting a control reaction (containing only buffer) to 1.0 for each reporter RNA. (C) Titration of Puf5p. Increasing concentrations of Puf5p were added to translation reactions containing either the HO or HO mut reporter.

The concentration of Puf5p needed for repression correlated well with the Kd of the protein for its binding site in the HO 3′UTR. Half-maximal repression required 45 nM protein, while the apparent Kd of the protein for its binding site in HO is ∼100 nM (Fig. 1C; Hook et al. 2007). The HO mut reporter was unaffected by levels of Puf5p threefold in excess of the Kd (Fig. 1C).

Kinetics of repression

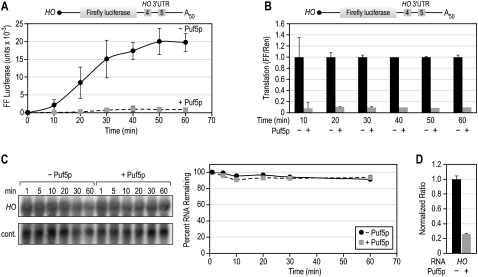

To examine the kinetics of repression, we quantitated firefly luciferase at 10-min time points throughout a 1-h incubation. In the absence of Puf5p, firefly luciferase activity increased throughout the hour and accumulated linearly from 10 to 30 min (Fig. 2A). In the presence of Puf5p, firefly luciferase levels were reduced at every time point. Thus, repression was continuous throughout the time course (Fig. 2A,B).

FIGURE 2.

Puf5p represses continuously. (A) Kinetics of translation and repression. Firefly and Renilla luciferase levels were measured every 10 min during a 1-h incubation at 30°C. (B) Kinetics as a proportion of total luciferase activity. The data in panel A are expressed as the level of firefly luciferase from the HO reporter over time in the presence or absence of Puf5p. (C) RNA stability. Total RNA was re-isolated from translation reactions at various time points during a translation reaction, and firefly luciferase mRNA was detected via Northern blot. The control (cont.) RNA is a 500-nt fragment of firefly luciferase added after the translation reaction ends to control for variation in RNA re-isolation. To verify that Puf5p was active in this experiment, luciferase levels were measured at the 60-min time point of the same incubations (D). (Right) The graph quantifies the mRNA levels. To determine the percent RNA remaining, background readings were subtracted from the HO signal and then divided by the signal of the control RNA, where the RNA detected at 1 min is assumed to be equal to 100%. (D) Puf5p was active in the assays analyzing kinetics (see panel C).

To examine the stability of the mRNA in the translation extract, we re-isolated RNA from the extract at 10-min time points and performed a Northern blot to detect firefly luciferase mRNA (Fig. 2C). Before the RNA was re-isolated, each sample was combined with a known amount of a control RNA to normalize for variations in the re-isolation process. Puf5p had no significant effect on mRNA stability during the translation assay (Fig. 2C). In the same experiments, we measured luciferase levels at the final time point and verified that Puf5p had been active (Fig. 2D). Thus, the decrease in luciferase activity was due to an effect on translation rather than on decay.

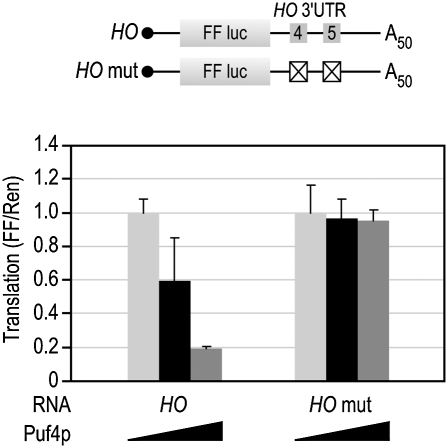

In vivo, HO is a target of both Puf4p and Puf5p (Goldstrohm et al. 2006; Hook et al. 2007). Puf4p was also active in vitro: purified recombinant Puf4p repressed the HO reporter to a comparable extent as Puf5p in a puf4Δ extract (Fig. 3). The effects of Puf4p and Puf5p were not additive (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Puf4p represses the HO reporter. Puf4p was added to translation reactions with either the HO or HO mut reporter. The final concentrations of Puf4p were 0, 0.5, or 2.5 μM.

Conservation

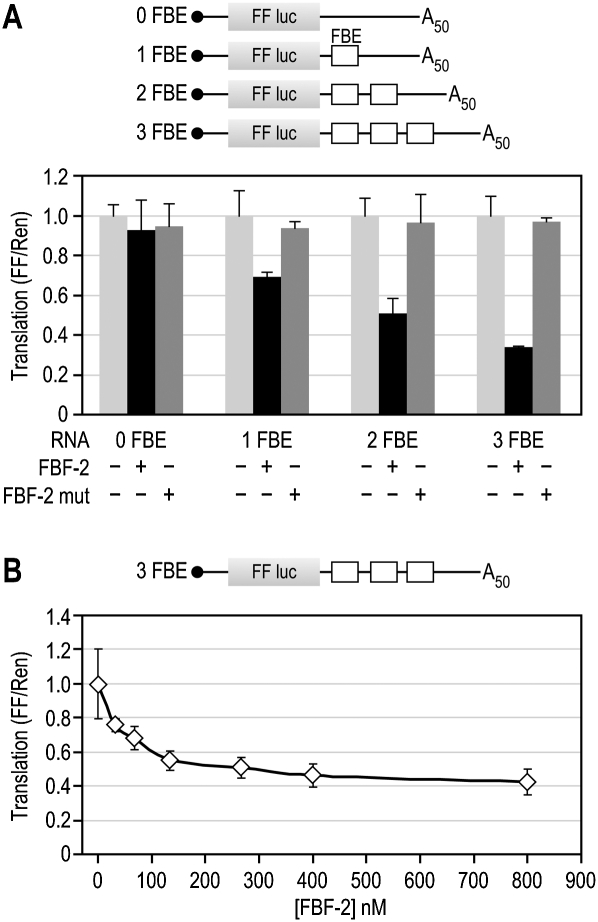

A PUF protein from C. elegans, FBF-2, also showed specific repression activity in yeast extracts. To test its activity, we used reporters bearing 0 to 3 binding sites for FBF, termed FBEs, in an unrelated 3′UTR. Reporters containing FBEs were repressed in the presence of FBF-2, and repression increased linearly as the number of FBEs increased (Fig. 4A). A control reporter that lacks FBEs, 0 FBE, was unaffected by FBF-2, and a mutant FBF-2 that cannot bind RNA had no effect on any reporter (Fig. 4A). FBF-2 repression was effective, requiring as little as 66 nM protein to effect significant repression of the 3 FBE reporter (Fig. 4B). Although the worm protein appeared to be less active than the yeast proteins, repression was specific. We conclude that molecular interactions required for PUF function are conserved from yeast to C. elegans.

FIGURE 4.

C. elegans FBF-2 is active in yeast extracts. (A) Repression by FBF-2 protein. Purified FBF-2 or an FBF-2 mutant was added to translation reactions with reporters containing 0–3 FBF binding elements (FBEs). FBF-2 specifically repressed only those reporters containing FBEs, and repression was directly correlated with the number of FBEs. The FBF-2 mutant protein contains alanine substitutions in the RNA-contacting residues of repeat 6 that greatly reduce its affinity for RNA. (B) Titration of FBF-2. Translation reactions containing the 3 FBE reporter were incubated with increasing concentrations of FBF-2.

Differential regulation

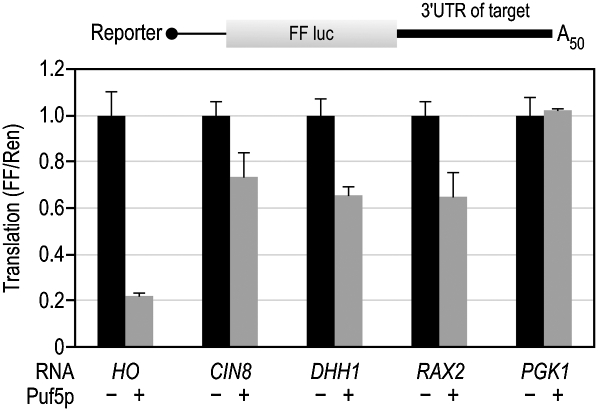

Puf5p regulates multiple mRNAs via their 3′UTRs. To compare the behavior of different targets in vitro, we constructed luciferase reporter mRNAs in which the 3′UTR was derived from a Puf5p target. We tested the 3′UTRs of CIN8, DHH1, and RAX2 mRNAs (see Introduction). As a control, we chose the PGK1 3′UTR because it contains no putative Puf5p binding sites and was negative in tests for Puf5p targets.

All three additional reporters were specifically repressed by Puf5p, while the control reporter was unaffected (Fig. 5). The extent of repression differed among mRNAs: The HO reporter was repressed more efficiently than the other three reporters. At the concentration of protein used (330 nM), HO was repressed by 80%, while CIN8, DHH1, and RAX2 were repressed by 30%–40%. We conclude that the HO 3′UTR mediated particularly efficient repression.

FIGURE 5.

Multiple target 3′UTRs mediate repression, but the HO 3′UTR is particularly efficient. Five reporters containing the firefly luciferase ORF and the 3′UTR from the mRNA indicated were tested in vitro. The PGK1 3′UTR served as a negative control (it is not a Puf5p target and contains no Puf5p binding elements). For detailed description of 3′UTRs, see Materials and Methods.

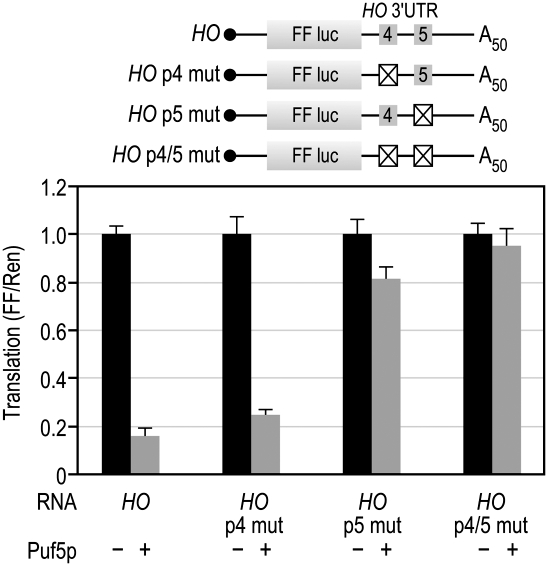

An element in the HO 3′UTR

We next sought to understand the basis of the enhanced repression of HO versus other mRNAs. The HO 3′UTR contains two PUF binding elements that recruit Puf4p and Puf5p. Puf5p can bind to the Puf4p site in the HO 3′UTR, albeit with reduced affinity (Hook et al. 2007). In principle, the Puf4p binding site might be responsible for enhanced repression of the HO reporter. To test this idea, we mutated each PUF site in the HO 3′UTR and assayed repression by Puf5p. The loss of the Puf5p binding site almost completely abrogated Puf5p repression, while the loss of the Puf4 binding site had only a marginal effect (Fig. 6). Therefore, the Puf5p site is sufficient to promote enhanced repression of HO.

FIGURE 6.

The Puf4p site is not required for repression. The HO 3′UTR was mutated to determine the contribution of each PUF binding element. For each site, the core “UGU” sequence was mutated to “ACA,” which eliminates PUF binding (Hook et al. 2007). The crossed-out boxes indicate the site that was mutated in each reporter.

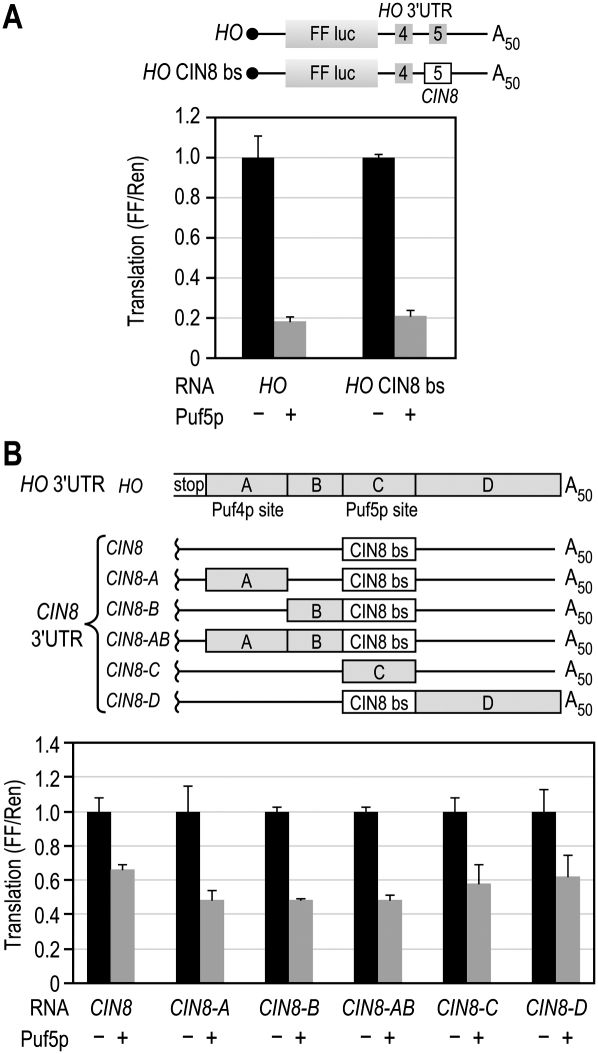

We next tested whether the identity of the Puf5p binding site was critical for repression. The CIN8 Puf5p binding site promotes intermediate repression in the context of the CIN8 3′UTR (Fig. 5). To determine whether the HO Puf5p binding site was responsible for the enhanced repression, we replaced it with the Puf5p binding site from CIN8 (Fig. 7A). The CIN8 Puf5p binding site was able to promote maximal repression from within the HO 3′UTR, indicating that the identity of the Puf5p binding site does not determine the level of repression for the HO reporter. All of the putative Puf5p sites in the four reporters have been tested previously using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to determine their relative affinity for Puf5p. In these assays, the Puf5p site in HO bound Puf5p twofold less tightly than did the binding sites in the RAX2 and CIN8 3′UTRs (Seay et al. 2006; Hook et al. 2007). Thus, repression and affinity were not well correlated. We therefore hypothesized that features outside the canonical binding site were responsible for enhanced repression activity of the HO 3′UTR.

FIGURE 7.

Segments of HO enhance repression of CIN8. (A) CIN8 versus HO binding sites. In the HO CIN8 bs reporter, the Puf5p binding site in the HO 3′UTR (UGUAUGUAAU) was replaced with the Puf5p binding site from the CIN8 3′UTR (UGUAAUAUU). (B) Chimeric 3′UTRs. The HO 3′UTR was divided into four segments that were then inserted into the 3′UTR of the CIN8 reporter while maintaining the same orientation and distance relative to the Puf5p site, as shown.

Role of additional sequences

To determine whether enhanced repression of HO was due to a discrete sequence outside of the canonical PUF binding sites, we created chimeric reporters using the HO and CIN8 3′UTRs. Sequences from the HO 3′UTR were placed in the CIN8 3′UTR while maintaining the same spacing relative to the Puf5p binding site (Fig. 7B). Two sequences from the HO 3′UTR enhanced repression of the CIN8 reporter: segment A, containing the Puf4p site, and segment B. The contributions of segments A and B were not additive; when both A and B were combined in mutant CIN8-AB, the level of repression was equivalent to either mutation alone (ANOVA, P ≥ 0.9, Fig. 7B). None of the chimeric reporters were repressed as well as the wild-type HO reporter. Since CIN8-B was significantly more repressed than CIN8 alone, the sequence between the two PUF sites in the HO 3′UTR may be important for regulation.

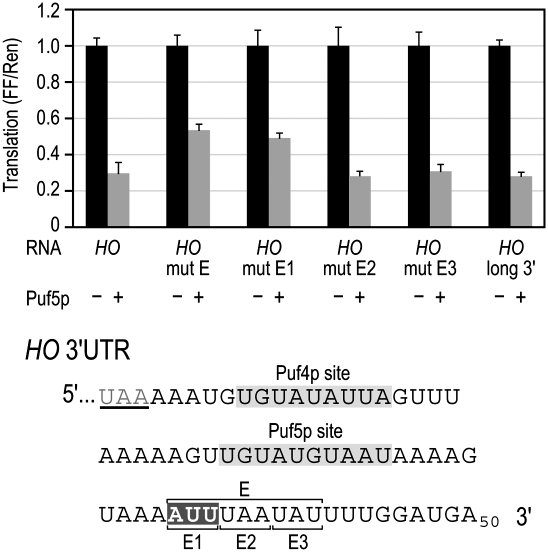

An element in the HO 3′UTR

To identify sequences important for regulation in the HO 3′UTR, we analyzed transversion mutations covering 8–10-nucleotide (nt) blocks across the HO 3′UTR, excluding the two PUF sites. Segment E, ∼10 nt downstream from the Puf5p binding site, showed significant de-repression (Fig. 8). We further narrowed down the critical region by subdividing segment E into 3-nt blocks, labeled E1–E3 (Fig. 8). The first 3 nt in segment E were identified as the most important for enhanced Puf5p repression.

FIGURE 8.

A sequence in the HO 3′UTR enhances Puf5p repression. A 9-nt mutation in the HO 3′ UTR, mut E, reduces repression. The mut E element was further subdivided into three mutants 3 nt long, E1–E3. Each mutant contained a transversion mutation in the bracketed sequence. Another variation of the HO reporter (HO long 3′) included an extra 25 nt of vector sequence that is present in all HO mutant reporters for technical reasons (see Materials and Methods). The sequences highlighted in gray indicate the PUF binding sites. The highlighted sequence constitutes the smallest region in mut E that is required for optimal repression of the HO 3′UTR.

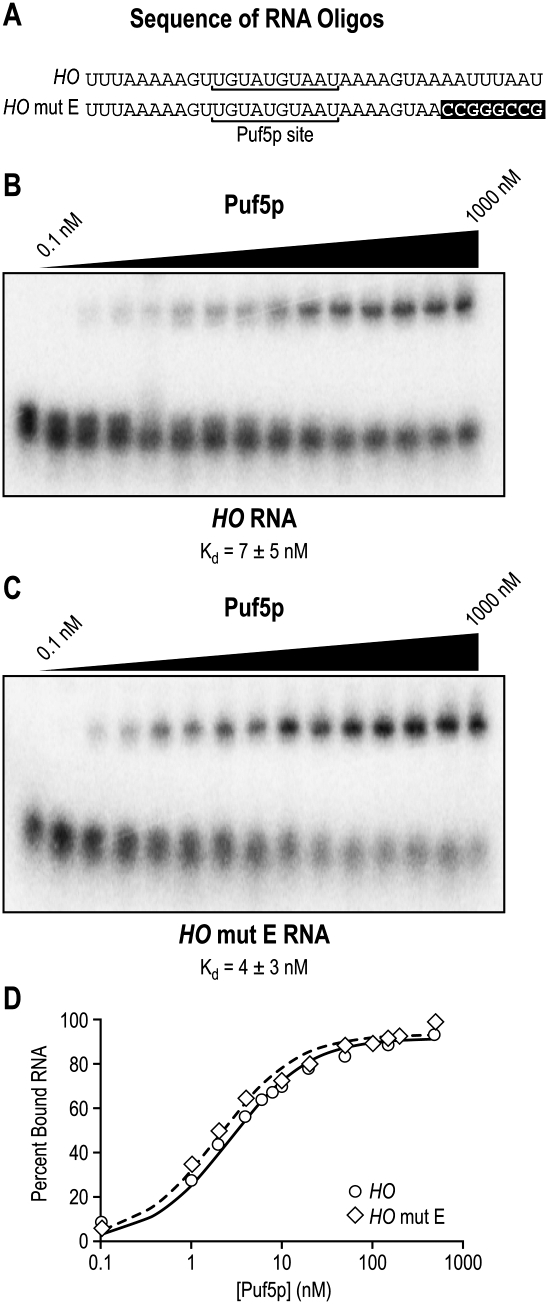

To rule out the possibility that the loss of repression seen with mut E was due to an effect on Puf5p binding, we assayed the relative affinity of Puf5p for HO or HO mut E using EMSAs (Fig. 9). A set of 5′-radiolabeled RNAs containing the Puf5p binding site with or without mut E was used in the EMSAs (Fig. 9A). Binding of Puf5p to the two RNAs was indistinguishable, demonstrating that segment E did not reduce repression activity by preventing the interaction with Puf5p (Fig. 9B–D). In contrast, other mutations in segments B and D (shown in Fig. 7) disturbed Puf5p binding (data not shown), and therefore were not pursued further. We conclude that segment E's role in repression is independent of Puf5p binding.

FIGURE 9.

Mutation of segment E does not affect Puf5p binding. (A) Complete sequences of the two RNA oligos used in EMSA analysis. The Puf5p site is underlined, and the mut E mutation is highlighted. (B,C) Representative EMSA autoradiograms. The lower band in each gel is radiolabeled unbound RNA and the upper band is RNA bound to Puf5p. The Kd shown was calculated from four independent experiments. (D) Quantitation. The fraction of RNA bound by Puf5p was plotted versus protein concentration.

Proximity to the ORF is important

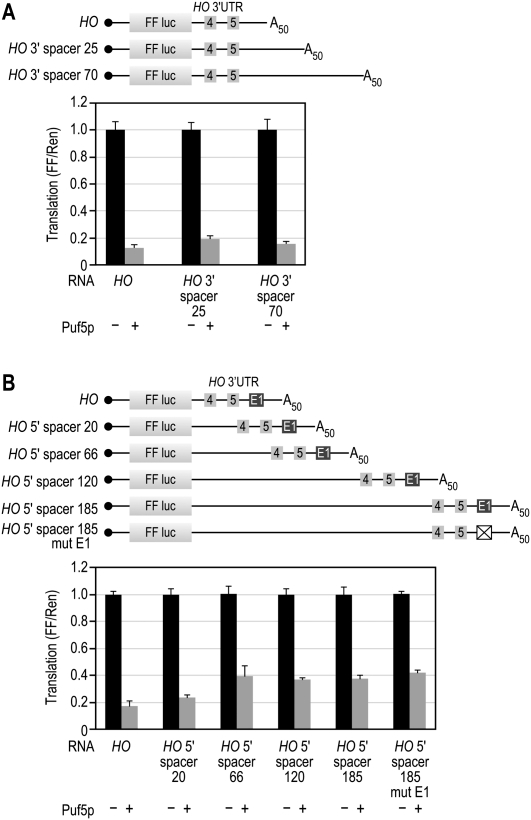

The HO 3′UTR is four times longer than that of CIN8 mRNA (253 vs. 67 nt). We considered the possibility that a longer 3′UTR might decrease the efficacy of repression. To test this idea, we used the HO 3′UTR as a scaffold, and introduced extra sequence on either the 5′ or 3′ end of the HO 3′UTR; the extra sequence was derived from vector sequence or “CA” repeats. Insertion of up to 70 nt between the PUF site and poly(A) tail did not affect repression (Fig. 10A). In contrast, insertion of 66 or more nucleotides between the ORF and the HO 3′UTR reduced repression significantly (P ≤ 0.001): expression of the reporter mRNAs doubled (Fig. 10B). The effect on repression reached a plateau at 66 nt from the ORF and was never abolished completely; thus, the distance effect only accounts for part of the enhanced repression mechanism.

FIGURE 10.

3′-UTR length affects repression. (A) The HO 3′UTR was expanded by the inclusion of either 25 or 70 extra bases of downstream vector sequence. (B) The 3′UTR was expanded by introducing random sequence between the stop codon and the HO 3′-UTR sequence. The number indicates the length of the additional sequence. The HO 5′-spacer 185 mut E1 contains both a spacer sequence and mutation E1 from Figure 5.

Since the reduction in repression closely matched the change in repression between HO and HO mut E, we tested whether mut E and an elongated 3′UTR might block the same interaction. If so, a mutant reporter with both a longer 3′UTR and mut E would behave similarly to either single mutant alone. An RNA carrying the longest 5′ spacer mutation and mut E1 was not repressed more efficiently than were RNAs carrying the individual mutations (P ≤ 0.001, Fig. 10B). We infer that both mutations perturb the same event.

DISCUSSION

The cell-free translation assay described here recapitulates PUF repression in vitro and demonstrates specific regulation for all three PUF proteins tested: yeast Puf4p and Puf5p, and C. elegans FBF-2. The specificity of the assay was validated by three criteria: only 3′UTRs from mRNA targets shown to be regulated in vivo were affected, the binding site and the PUF protein's binding activity were both required, and the amount of protein required for repression was comparable to its apparent Kd for the RNA. The non-canonical yeast protein Puf6p required substantially more protein to repress in analogous assays (Deng et al. 2008). Using the cell-free translation assay, we verified that Puf5p regulates three targets in addition to HO: DHH1, RAX2, and CIN8. Indeed, validation of targets may be a useful adjunct of the system. Differences in mechanisms of regulation among target mRNAs may be more easily discerned in the extract than in vivo.

FBF-2, a C. elegans PUF, was active in the yeast extract. Therefore, FBF-2 must be able to productively interact with yeast proteins to enact repression. Although FBF-2 appeared to be less active than the two yeast PUF proteins, the binding elements were suboptimal. Regardless, the ability of a PUF protein to function in the context of a different species demonstrates that PUF protein interactions, and likely function, are conserved.

The HO 3′UTR mediated more efficient repression than the other 3′UTRs tested. Our studies identified at least two contributing factors that underlie this efficiency: specific sequence elements, and distance between the PUF sites and termination codon. Mutational analysis of the HO 3′UTR revealed three sequence elements outside of the canonical PUF binding sites required for maximum repression by Puf5p. Two of the three mutations reduced the affinity of Puf5p for the RNA and therefore were unlikely to play a mechanistic role (data not shown). The third mutation uncovered an “AUU” sequence (identified as “mut E1” in Fig. 8) required for maximal repression of the HO reporter. In addition to this element, the distance between the termination codon and the HO 3′UTR was important: insertion of 66 nt or more reduced repression (Fig. 10). A double-mutant HO reporter combining the “AUU” mutation with a longer 3′UTR was repressed to the same extent as either single mutant (Fig. 10). From this finding, we infer that both mutations perturb the same mode of repression. The effects of distance between the ORFs and PUF sites suggest communication with the translating or terminating ribosome. However, we have not measured either elongation or termination directly, and other interpretations are possible. Puf6p, a non-canonical PUF protein, regulates 60S joining via an interaction with eIF5B (Deng et al. 2008). Repression by Puf6p requires its N-terminal region, outside the RNA-binding domain; in contrast, the RNA-binding domains of the PUF proteins tested here are sufficient for repression. This suggests that the mechanisms of repression by Puf5p and Puf6p differ, but further studies will be required to test this notion definitively.

We propose a model in which Puf5p recruits a partner repressor protein via the “AUU” element in the HO 3′UTR. We speculate that the resulting complex disrupts translation elongation or termination. Thus, the PUF protein and its segment E partner interfere with translation. The cell-free system we have described should enable tests of this model, including the basis of the distance effect, identification of the proposed partner protein, and elucidation of the mechanism of repression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains

All yeast extracts were derived from the S. cerevisiae strain MBS (MATa ade2-1 his3-11,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 can1-100 [rho þ ] L-o, M-o) with the exception of the MBS puf4Δ extract (Iizuka and Sarnow 1997; Wu et al. 2007). The MBS puf4Δ is a puf4∷HIS3 derivative of MBS constructed for this study (Longtine et al. 1998).

Protein expression constructs and purification

The recombinant Puf4p and Puf5p protein expression constructs used in this study have been described previously (Hook et al. 2007). The RNA-binding defective mutant of Puf5p has four mutations in PUF repeats 7 and 8: S455A, N456A, N520A, and Y521A. The FBF-2 expression construct (amino acids 121–632) has also been described previously (Bernstein et al. 2005). The FBF-2 RNA-binding defective mutant carries three mutations in repeat 6: N294A, Y295A, and Q298A. The resultant GST fusion proteins were isolated from BL-21 gold E. coli cells (Invitrogen) and purified as described using the following elution buffer: 5 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.4), 30 mM potassium acetate, 0.5 mM magnesium acetate, 20% glycerol, 0.5 mM DTT, and 20 mM glutathione (reduced) (pH 8.0) (Bernstein et al. 2005).

Luciferase constructs and synthetic mRNAs

pSP65A, a gift from Allan Jacobson's laboratory (University of Massachusetts Medical School), contains the 5′UTR from the CAN1 mRNA, the firefly luciferase ORF, and the 3′UTR from PGK1. pSP65-Ren was created by replacing the firefly luciferase ORF with the Renilla luciferase ORF in pSP65A. The control Renilla reporter was transcribed from a PCR product amplified from pSP65-Ren that began at the SP6 promoter and ended at the poly(A) tract. The HO luciferase reporter was transcribed from the pYC2-HO plasmid. pYC2-HO contains sequence from the HO locus spanning 2000 nt upstream to 1000 nt downstream from the ORF with the ORF replaced by the firefly luciferase gene. The PCR template used for transcription included 8 nt upstream of the ATG of luciferase and the 67-nt HO 3′UTR. A T3 promoter and a 50-nt poly(A) tail were added 5′ and 3′, respectively, by an additional primer sequence. For the HO 3′-UTR mutants, the reverse primer included an additional 25 nt of vector sequence to avoid overlapping with the mutations. The reporters containing 0–3 FBEs were transcribed from the pGL3 promoter v2 plasmid (Promega) with 1, 2, or 3 FBEa sequences (derived from the 3′UTR of the gld-1 mRNA from C. elegans) introduced by oligo ligation into the XbaI site (Crittenden et al. 2003).

The CIN8, DHH1, PGK1, and RAX2 reporters were assembled by ligation of the firefly luciferase ORF and the 3′UTR of interest and PCR selecting for the final product. The PCR product was then cloned into pET-15b using the XhoI and HindIII sites. The 3′-UTR length was chosen based on data from a tiling array of the yeast transcriptome (David et al. 2006). The 3′-UTR sequences included downstream from the stop codon for each reporter are: HO, 67 nt; CIN8, 253 nt; DHH1, 167 nt; PGK1, 76 nt; and RAX2, 89 nt. PCR templates were created using a primer specific to the 5′ end of firefly luciferase and the vector sequence directly downstream from the HindIII site. The reverse primer also coded for a 50-nt poly(A) tail. All PCR products were subsequently prepared for transcription by phenol/chloroform extraction, ethanol precipitation, and resuspended in DEPC-treated water. RNA was transcribed from the PCR products using the MEGAscript kit (Ambion) with 20% of the suggested GTP and 6 mM 7mG cap analog (New England Biolabs).

Preparation of yeast extracts and translation reactions

Yeast extracts were prepared as described, and yeast were lysed by the liquid nitrogen grinding method (Iizuka and Sarnow 1997). Extracts were treated with micrococcal nuclease (Takara) for 10 min at room temperature, and the reaction was quenched with EGTA. Extracts were then stored in 150-μL aliquots at −80°C. For each extract, a titration was performed to determine the volume of extract that maximized translation (typically 3–5 μL of 15–20 mg/mL extract). For analysis of repression by Puf4p (Fig. 4), extract was prepared from a Δpuf4 strain (see strains).

Translation reactions were assembled using ∼60 μg of yeast extract, 10 ng of firefly reporter RNA, 30 ng of Renilla reporter RNA, 2.5 μL of 6× translation buffer, 1 μL of 4mg/mL creatine kinase, and 0.1 μL of RNasin (Promega) in a 15-μL reaction (Iizuka and Sarnow 1997). Reactions were incubated for 60 min at 30°C, and then luciferase levels were measured. Both firefly and Renilla luciferase levels were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System from Promega on a Turner 20/20n luminometer with a 10-sec integration for both measurements according to the manufacturer's directions.

Northern blots

Translation reactions to assay mRNA stability were performed under the same conditions as described above except the concentration of firefly reporter RNA was increased to 100 ng per 15-μL reaction. At each time point, 15 μL of translation reaction was added to 185 μL of stop buffer and mixed vigorously. Stop buffer: 7 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 33 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 20 mg proteinase K, and 2 ng of control luc fragment RNA was added to control for variations in RNA re-isolation. Luc fragment RNA consisted of nucleotides 1150–1652 of firefly luciferase. After the addition of stop buffer, reactions were incubated for 30 min at 37°C to allow proteinase K digestion, and subsequently extracted with phenol/chloroform and ethanol precipitated. Ten percent of the purified RNA was loaded onto a 1.0% agarose, 3.7% formaldehyde, 1× MOPS gel, and run for 2 h at 100 V. RNA was transferred overnight onto a charged nylon membrane (Millipore) by capillary action using 10× SSC. Blots were hybridized in Ultrahyb (Ambion) and washed according to the manufacturer's directions. The probe used to detect firefly luciferase was complementary to nucleotides 1131–1640 of firefly luciferase and was internally labeled with [α-32P]UTP.

EMSAs

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays were performed and analyzed as previously described (Koh et al. 2009) except the reaction buffer consisted of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/mL BSA, and 0.02% Tween 20 (v/v). The differences between our reported Kds and those previously reported is likely due to variations in protein activity and the lack of competitor RNA in our assays. Our EMSAs were performed only for comparison of the two RNA oligos indicated. The Kd values and standard errors reported were from four independent experiments.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shubhendu Ghosh and Allan Jacobson at the University of Massachusetts Medical School for providing strains, reagents, and protocols for the cell-free translation experiments. We also thank members of the Wickens laboratory for advice and discussion. We thank Laura Vanderploeg and the Biochemistry Media Laboratory for help with figure preparation. M.W. is supported by grants from the NIH (GM31892 and GM50942). J.J.C. was supported by the NIH Genetics Training Grant (UW-Madison) during this work.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2070110.

REFERENCES

- Bernstein D, Hook B, Hajarnavis A, Opperman L, Wickens M 2005. Binding specificity and mRNA targets of a C. elegans PUF protein, FBF-1. RNA 11: 447–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broach JR 2004. Making the right choice–long-range chromosomal interactions in development. Cell 119: 583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnovich D, Lehmann R 2001. Poly(A)-independent regulation of maternal hunchback translation in the Drosophila embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 11359–11364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho PF, Gamberi C, Cho-Park YA, Cho-Park IB, Lasko P, Sonenberg N 2006. Cap-dependent translational inhibition establishes two opposing morphogen gradients in Drosophila embryos. Curr Biol 16: 2035–2041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collart MA 2003. Global control of gene expression in yeast by the Ccr4-Not complex. Gene 313: 1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JM, Tucker M, Sheth U, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Parker R 2001. The DEAD box helicase, Dhh1p, functions in mRNA decapping and interacts with both the decapping and deadenylase complexes. RNA 7: 1717–1727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma MP 2004. Daughter-specific repression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO: Ash1 is the commander. EMBO Rep 5: 953–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden SL, Eckmann CR, Wang L, Bernstein DS, Wickens M, Kimble J 2003. Regulation of the mitosis/meiosis decision in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 358: 1359–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L, Huber W, Granovskaia M, Toedling J, Palm CJ, Bofkin L, Jones T, Davis RW, Steinmetz LM 2006. A high-resolution map of transcription in the yeast genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 5320–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Singer RH, Gu W 2008. Translation of ASH1 mRNA is repressed by Puf6p-Fun12p/eIF5B interaction and released by CK2 phosphorylation. Genes Dev 22: 1037–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis CL, Chen J 2003. The CCR4-NOT complex plays diverse roles in mRNA metabolism. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 73: 221–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman V, Gerson-Gurwitz A, Movshovich N, Kupiec M, Gheber L 2009. Midzone organization restricts interpolar microtubule plus-end dynamics during spindle elongation. EMBO Rep 10: 387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galgano A, Forrer M, Jaskiewicz L, Kanitz A, Zavolan M, Gerber AP 2008. Comparative analysis of mRNA targets for human PUF-family proteins suggests extensive interaction with the miRNA regulatory system. PLoS One 3: e3164 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner MK, Bouck DC, Paliulis LV, Meehl JB, O'Toole ET, Haase J, Soubry A, Joglekar AP, Winey M, Salmon ED, et al. 2008. Chromosome congression by Kinesin-5 motor-mediated disassembly of longer kinetochore microtubules. Cell 135: 894–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer F, Hentze MW 2007. Studying translational control in Drosophila cell-free systems. Methods Enzymol 429: 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO 2004. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol 2: e79 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Luschnig S, Krasnow MA, Brown PO, Herschlag D 2006. Genome-wide identification of mRNAs associated with the translational regulator PUMILIO in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 4487–4492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstrohm AC, Hook BA, Seay DJ, Wickens M 2006. PUF proteins bind Pop2p to regulate messenger RNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstrohm AC, Seay DJ, Hook BA, Wickens M 2007. PUF protein-mediated deadenylation is catalyzed by Ccr4p. J Biol Chem 282: 109–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata H, Mitsui H, Liu H, Bai Y, Denis CL, Shimizu Y, Sakai A 1998. Dhh1p, a putative RNA helicase, associates with the general transcription factors Pop2p and Ccr4p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 148: 571–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook BA, Goldstrohm AC, Seay DJ, Wickens M 2007. Two yeast PUF proteins negatively regulate a single mRNA. J Biol Chem 282: 15430–15438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iizuka N, Sarnow P 1997. Translation-competent extracts from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Effects of L-A RNA, 5′ cap, and 3′ poly(A) tail on translational efficiency of mRNAs. Methods 11: 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyrova LY, Habara Y, Lee TH, Wharton RP 2007. Translational control of maternal Cyclin B mRNA by Nanos in the Drosophila germline. Development 134: 1519–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye JA, Rose NC, Goldsworthy B, Goga A, L'Etoile ND 2009. A 3′UTR Pumilio-binding element directs translational activation in olfactory sensory neurons. Neuron 61: 57–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klar AJ 2007. Lessons learned from studies of fission yeast mating-type switching and silencing. Annu Rev Genet 41: 213–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YY, Opperman L, Stumpf C, Mandan A, Keles S, Wickens M 2009. A single C. elegans PUF protein binds RNA in multiple modes. RNA 15: 1090–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuersten S, Goodwin EB 2003. The power of the 3′ UTR: Translational control and development. Nat Rev Genet 4: 626–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A III, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillet L, Collart MA 2002. Interaction between Not1p, a component of the Ccr4-not complex, a global regulator of transcription, and Dhh1p, a putative RNA helicase. J Biol Chem 277: 2835–2842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews M, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB 2007. Translational control in biology and medicine Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Miller MT, Higgin JJ, Hall TM 2008. Basis of altered RNA-binding specificity by PUF proteins revealed by crystal structures of yeast Puf4p. Nat Struct Mol Biol 15: 397–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshall N, Thom G, Standart N 2001. A conserved role of a DEAD box helicase in mRNA masking. RNA 7: 1728–1742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasmyth K 1993. Regulating the HO endonuclease in yeast. Curr Opin Genet Dev 3: 286–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pique M, Lopez JM, Foissac S, Guigo R, Mendez R 2008. A combinatorial code for CPE-mediated translational control. Cell 132: 434–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seay D, Hook B, Evans K, Wickens M 2006. A three-hybrid screen identifies mRNAs controlled by a regulatory protein. RNA 12: 1594–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda J, Wharton RP 2001. Drosophila brain tumor is a translational repressor. Genes Dev 15: 762–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh N, Crittenden SL, Goldstrohm A, Hook B, Thompson B, Wickens M, Kimble J 2009. FBF and its dual control of gld-1 expression in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Genetics 181: 1249–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadauchi T, Matsumoto K, Herskowitz I, Irie K 2001. Post-transcriptional regulation through the HO 3′-UTR by Mpt5, a yeast homolog of Pumilio and FBF. EMBO J 20: 552–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, McLachlan J, Zamore PD, Hall TM 2002. Modular recognition of RNA by a human Pumilio-homology domain. Cell 110: 501–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Opperman L, Wickens M, Hall TM 2009. Structural basis for specific recognition of multiple mRNA targets by a PUF regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 20186–20191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton RP, Aggarwal AK 2006. mRNA regulation by Puf domain proteins. Sci STKE 2006: pe37 doi: 10.1126/stke.3542006pe37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M, Bernstein DS, Kimble J, Parker R 2002. A PUF family portrait: 3′UTR regulation as a way of life. Trends Genet 18: 150–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Amrani N, Jacobson A, Sachs MS 2007. The use of fungal in vitro systems for studying translational regulation. Methods Enzymol 429: 203–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]