Abstract

Typical 2-Cys peroxiredoxins (Prxs) are peroxidases which regulate cell signaling pathways, apoptosis, and differentiation. These enzymes are obligate homodimers, and can form decamers in solution. During catalysis, Prxs exhibit cysteine-dependent reactivity which requires the deprotonation of the peroxidatic cysteine (Cp) supported by a lowered pKa in the initial step. We present the results of molecular dynamics simulations combined with pKa calculations on the monomeric, dimeric and decameric forms of one typical 2-Cys Prx, the tryparedoxin peroxidase from Trypanosoma cruzi (PDB id, 1uul). The calculations indicate that Cp (C52) pKa values are highly affected by oligomeric state; an unshifted Cp pKa (~ 8.3, comparable to the pKa of isolated cysteine) is calculated for the monomer. In the dimers, starting with essentially identical structures, the Cps evolve dynamically asymmetric pKas during the simulations; one subunit’s Cp pKa is shifted downward at a time, while the other is unshifted. However, when averaged over time, or multiple simulations, the two subunits within a dimer exhibit the same Cp, showing no preference for a lowered pKa in either subunit. Two conserved pathways that communicate the asymmetric pKas between Cps of different subunits can be identified. In the decamer, all the Cp pKas are shifted downward, with slight asymmetry in the dimers which form the decamers. Structural analyses implicate oligomerization effects as responsible for these oligomeric state-dependent Cp pKa shifts. The intra-dimer and the inter-dimer subunit contacts in the decamer restrict the conformations of the side chains of several residues (T49, T54 and E55) calculated to be key in shifting the Cp pKa. In addition, the backbone fluctuations of a few residues (M46, D47 and F48) result in a different electrostatic environment for the Cp in dimers relative to the monomers. These side chain and backbone interactions which contribute to pKa modulation indicate the importance of oligomerization to the function of the typical 2-Cys Prxs.

Keywords: peroxiredoxins, MD simulations, MEAD

Introduction

The peroxiredoxin proteins (Prxs) represent one of the most abundant enzyme families in cells of all phylogenetic origins (1–6). The molecular function of these enzymes is to catalyze the reduction of hydrogen peroxide, alkyl hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite, all important products of oxidative and nitrosative metabolism (6–8). Recent research has also implicated these proteins in the regulation of signaling cascades in higher organisms, which may be important in mediating cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (4, 7, 9–12).

Although Prxs have been the subject of various structural and functional studies (13), many details of their molecular mechanism remain elusive, especially those aspects of the protein structure that facilitate cysteine deprotonation. The common chemistry shared by the entire Prx family requires the activation of a cysteine known as the peroxidatic cysteine (Cp) (6), by deprotonation in the first step of the catalytic cycle. This cysteine is conserved throughout the entire Prx family (6–8). The deprotonated form of Cp then attacks the peroxide, releasing the alcohol product and leading to the formation of a cysteine sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH) intermediate on the enzyme (6). A model describing this mechanism has been proposed in which the microenvironment of the protein somehow causes a lowered Cp pKa. A proton is then abstracted from Cp via an unknown base (6).

Based on the number of cysteine residues directly involved in catalysis, Prxs were originally divided into two categories, the 1-Cys and 2-Cys Prxs. For the 2-Cys Prxs, a second cysteine (the resolving cysteine, Cr) condenses with the Cys-SOH to form a disulfide bond prior to reduction. The 2-Cys Prxs can be further subdivided into typical and atypical 2-Cys Prxs. A disulfide bond is formed between Cp and Cr from different subunits in the typical 2-Cys Prxs, and usually within a single subunit in the atypical 2-Cys Prxs. Typical 2-Cys Prxs are required to be, minimally, dimers as the inter-subunit disulfide bond formation is a step in the mechanism (14, 15). However, they have also been observed to oligomerize into decamers in solution and in crystal structures (14–17). Typical 2-Cys Prxs are functional both in the dimeric and decameric states and several researchers have reported that Prx dimers exhibit lower activities than the decameric proteins (18–20).

The activation and the maintenance of the deprotonated state of Cp are crucial to Prx function, thus understanding how the active site microenvironment causes the lowered Cp pKa is particularly important. Towards this end, this paper presents the results of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations combined with electrostatics analysis on several oligomeric forms of tryparedoxin peroxidase (TryP) from Trypanosoma cruzi. These results provide valuable insight into the effects of dimerization or decamerization on the Cp pKa by examining the pKa variation in different oligomeric states as well as the influence of active site residue conformations on the pKa shift. Molecular Dynamics is a powerful method to investigate structural and dynamical information of macromolecular structure in atomic details, and its application to a wide variety of biological systems has recently been published in this journal (21–33).

Materials and Methods

Starting crystal structures of tryparedoxin peroxidase

Tryparedoxin peroxidase from Trypanosoma cruzi (PDB id, 1uul) (34), a representative example of a typical 2-Cys Prx, was used as the starting structure for all simulations; 1uul provided a high quality structural model generated from 2.8 Å resolution data and having an Rfree value of 0.251. The crystal structure (Figure 1) is composed of ten subunits labeled from A to J (Figure 1C). Dimers are formed between two neighboring subunits, for example dimer AB, dimer CD, etc (Figure 1B). The biologically functional state of tryparedoxin peroxidase is expected to be the decamer observed in the crystal structure, arranged as a pentamer of dimers (Figure 1C). There are two types of interfaces within the decamer, which are defined according to the structure (17, 35). The B-type interface (B for “β-sheet” based) is the interface between subunits in a dimer, such as the interface between subunits A and B shown in Figure 1B. The disulfide bond between Cp and Cr is located at this interface. The A-type interface (A for “alternate” or for “ancestral”) (13) is the interface between dimers forming the decamer, such as the interface between subunits B and C (17, 35 – 38). All subunits are fully reduced in the 1uul crystal structure. The peroxidatic (Cp) and resolving cysteines (Cr) are residues 52 and 173, respectively.

Figure 1.

Cartoon diagrams of the monomeric (A), dimeric (B), and decameric (C) form of tryparedoxin peroxidase (PDB id, 1uul). In each panel, subunit A is in blue and subunit B is in red. The peroxidatic cysteines (Cp, residue 52) are shown as yellow Van der Waal spheres; the resolving cysteines (Cr, residue 173) are shown as red spheres. Tryparedoxin peroxidase is a typical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin; the biological active site consists of a Cp and a Cr in each subunit (A) and there are two active sites per dimer (B). In solution, five dimers usually form a toroid-shaped decamer (C). The dimer (B) and the decamer (C) are the biologically relevant structures.

Molecular dynamics (MD) protocol

Simulations of the monomeric, dimeric and decameric forms of tryparedoxin peroxidase from T. cruzi were performed to gain insight into the relationship between structure and function of Prxs.

The crystal structure of 1uul was used as the starting structure for all simulations. Hydrogen atoms were first added at standard positions in the protein structure, using standard CHARMM commands (39). Three steps of steepest descent minimization (500 cycles each with heavy atom constraints of 30, 20, and 10 kcal/mol) were then performed to avoid poor steric contacts. The resulting structure was solvated in a box of water molecules described by the TIP3P water model (40). The water molecules were briefly minimized for 100 cycles of conjugate gradient minimization with a small harmonic force constant on all protein atoms. The entire system then underwent 225 ps of MD simulation to achieve a thermal equilibration using Berendsen pressure regulation with isotropic position scaling (41). The temperature was reassigned from a Boltzmann distribution every 1000 cycles, in 25 K increments, from an initial temperature of 0 K to a target temperature of 300 K. Each simulation was started with different random seeds for the initial velocities. All heavy atom and hydrogen atom bonds were held by the SHAKE algorithm (42). A time step of 2.0 fs was used. The charge interactions were taken into account using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method, utilizing a ~ 1 Å resolution grid (43).

Following the equilibration, dynamics simulations were performed using the NAMD package (31), under the NVE ensemble, utilizing PME for the electrostatic interactions. The CHARMM22 parameter set and forcefield (39) as implemented within the NAMD package were used. The initial coordinates, velocities, and system dimensions were taken from the final state of the corresponding equilibration simulation.

Cluster analysis

To determine the most occupied conformations during the time course of these simulations, hierarchical clustering was performed using average link clustering (45). The final clusters were determined by minimizing the Pi value (a measure of cluster compactness) (46). The conformation best representing the structures in a given cluster was obtained by finding the cluster member possessing the minimum root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of the backbone atoms from all other members of that cluster (47).

pKa calculations and cysteine pKa values

Electrostatic calculations have been used extensively, especially since the early 1990’s, to calculate pKas of protein amino acid side chains (49–54). One of the more developed methods uses the macroscopic electrostatics with atomic detail (MEAD) model (49,50), in which the protein is treated as an irregularly shaped low-dielectric object with embedded partial charges surrounded by a high dielectric medium (e.g. water). The dielectric constant of protein is set as 20 (52). The crystal structure of a protein is used to define the boundary between protein and solvent. Van der Waals radii (55) and charges of all atoms are obtained from CHARMM22 force field. The result is discretized onto a grid for the finite difference calculations. The resulting grid of the charges and the dielectric regions can be used to solve the finite difference linear Poisson-Boltzmann (FDPB) equations at a particular ionic strength, i.e., 0.15 mM. The solution of the FDPB equation gives electrostatic potentials and electrostatic energies from changes in the charge distributions can then be easily calculated (55)

MEAD has been used in this study primarily for two reasons. First, there exist parameters recently validated for Cys and Thr studies (56) for use with MEAD, and second, using a FDPB-based calculation allows for the easy identification of interactions between different titratable residues, so as to identify important interacting residues.

These Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) based calculations are applied to pKa calculations by using reference states and model compounds (49, 52–54,56). A typical reference state is the one in which all the titratable residues are protonated. In this work, every Ser, Asp, Arg, Glu, His, Cys, Lys and Tyr residue was considered titratable. In general, Thr is not considered as an ionizable residue given its high pKa (15.0, (48)). However, our previous results (56) suggest that this residue might be important for the function of Cp. Therefore, Thr was included as a titratable residue in this work so that its effect on the Cp pKa can be assessed. Model compounds (57) are used to parameterize the parts of protonation / deprotonation which classical MD cannot handle, such as bond breaking, or solvation of a single proton. A model compound parameter set for a given amino acid consists of the charges of the protonated and deprotonated states and the pKa for a reference compound. The FDPB calculations determine the energy required to change from one protonation state to another, and that energy results in shifting the residue pKa away from the reference pKa.

In theory, three kinds of electrostatic terms influence the pKa of titratable residues, (1) interactions due to being in the lower-dielectric protein (Born energy term ΔΔGborn), (2) interactions between the residue of interest and non-titrating charges (background energy term ΔΔGback), and (3) interactions between the charged forms of the titratable residues (site-site interaction). The Born term may be changed due to differences in solvent accessibility. A protein’s backbone and side chain fluctuations can shift the background term. The site-site interaction between site i and site j is the additional electrostatic work needed to change site i’s charges from the reference state to the deprotonated state, if site j is deprotonated instead of in its reference state. It has the same unit as energy and is usually converted into pK units (one pK unit is equivalent to 1.4 kcal/mol at 300 K). In this paper, the magnitude of site-site interaction is called interaction energy. All of these terms are calculated from the FDPB equation. Since Born and background terms are irrelevant to the protonation states of other titratable residues, they can be combined with the model compound pKa (pKmod) to give the “intrinsic pKa”,

| (1) |

This pKa is referred to as intrinsic as it is what the pKa would be for a specific residue if nothing else in the protein were titratable.

To determine the full pKa, the effects of site-site interactions must be considered. In principle, to determine the pKas exactly requires determining the energetic effects of deprotonating more than two residues simultaneously (50) and the enumeration should be performed on all 2n possible protonation states. Even a small number of residues will make the computation intractable. Monte Carlo sampling is used here to determine protonation fraction of each residue at a given pH, and the pKa is the pH where the protonation fraction is ½ (49).

Generally, the pKa of an isolated cysteine residue is about 8.3 (48). With the presence of other titratable and non-titratable residues in its microenvironment, the actual pKa of cysteine in the protein can be shifted. Our previous results (56) demonstrate that MEAD can be used to estimate the cysteine pKa values for Prx family of proteins in the crystal structures. In this paper, pKas of cysteine ranging from 8.0 to 8.6 are designated as unshifted pKa, while pKas of cysteine lower than 8.0 are considered lowered pKas.

Combined MD simulations with pKa calculations

To provide insight into the effect of conformational fluctuations on pKa values of active site residues, MD simulations are combined with pKa calculations to analyze electrostatics. During the course of each simulation, structures were selected at every 5 ps and electrostatic calculations were performed on each structure. For each of these structures, the pKa values of important residues, including the Born term, background term and site-site interactions, were calculated. Grouping these results illustrates how pKa evolves over the simulation time, as well as how structural changes affect the electrostatic properties.

This approach differs from a constant-pH approach in which protonation and deprotonation are coupled (57,58). In this approach, the use of normal molecular dynamics simulations with MEAD considers each simulated structure as a model for the environment of the relevant cysteine. This approach does not explicitly couple the protonation and deprotonation of the cysteine to the dynamics of the rest of the protein. While such a coupling would be advantageous under some circumstances, current methods, such as those developed in CHARMM (57) and AMBER (58), presently are not well-parameterized for cysteine as MEAD is (56), do not have the extensive validation of PB-based methods (49–54) for native state simulations, and do not allow, yet, for the careful piecing out of site-site interactions as is done in the present study. Constant pH-methods would, however, be the method of choice for protein folding studies, where such coupling is necessary

Sequence alignment

Sequence alignment of Prxs has been done by other researchers (4). However, to determine which residues are conserved in the typical 2-Cys Prxs, sequence alignment was performed. A total of 38 proteins randomly selected from each major subfamily of typical 2-Cys Prxs are included in the list. The sequence alignment was performed by using Clustal X (60), and the result is shown in Figure S1.

Results and Discussion

Structural and electrostatic similarities among TryP monomers in the crystal structure

Before doing MD simulations, the crystal structure of tryparedoxin peroxidase (TryP) was analyzed for similarities between the subunits. The backbone and all-atom RMSDs between subunit A and all the other subunits in the crystal structure were compared and were all found to be less than 0.7 (Table SI). Accordingly, the peroxidatic cysteines, C52 (Cp), of all subunits have similar pKa values, 7.0 – 7.2 (Table SI).

Unshifted Cp pKa of monomer suggests decreased activity for monomeric TryP at neutral pH

Two monomer simulations were performed, one on subunit A and one on subunit B, of 11.4 and 10.5 ns in length respectively. These two simulations were used to explore the effects of slight heterogeneity of the initial structure on the calculations. The Cp pKas of these two subunits, with similar initial values (7.2, 7.1, Table SI) in the crystal structure, increased significantly until a stable pKa value of ~8.1 was reached after 4.5 ns (Figure 2A). At the end of each simulation, the two subunits both showed unshifted Cp pKa values compared to the pKa of isolated cysteine. The average Cp pKa of the subunits A and B simulations were 8.64 and 8.01, respectively. Over the entirety of both simulations, only 4% of all the calculated structures have a Cp pKa less than 7.0, the approximate pH of the physiological environment. Moreover, 96.3% of the structures have a Cp pKa greater than 7.5 pK units after 4.5 ns. The pKa values exhibited by the Cp residues in monomeric forms of the two subunits suggest that, under physiological pH conditions, only a minor portion of the Cp residues would be deprotonated and thus, the protein would be largely inactive.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the Cp side chain pKa in (A) the monomer simulations (B) the first dimer simulation and (C) the second dimer simulation. The pKas for subunits A and B are depicted in black and gray, respectively.

Asymmetry between subunit Cp pKa values within dimers suggests half-site reactivity of TryP

Two dimer simulations (10.6 ns and 14.9 ns) were performed on dimer AB which is a dimer across the B interface. While the initial structures of these two simulations were the same, the initial velocities of atoms in each simulation were different. Comparisons between these two simulations were useful for exploring the effects of variable initial conditions on the same starting structures and the Cp pKa in the dimer structure.

Although the initial structural and electrostatic differences between subunits A and B in the crystal structure are negligible, both simulations show the development of asymmetric Cp pKas shortly after initiation (Figure 2B and C). During the course of the first dimer simulation, subunit B’s Cp pKa was elevated while subunit A’s Cp pKa did not change significantly. The asymmetry became apparent at around 3 ns and continued throughout the entire simulation (Figure 2B). At the end of this first simulation, the backbone and all atom RMSDs between subunits A and B were 2.77 Å and 3.57 Å, and the Cp pKa values were 6.8 and 8.2, respectively, which is significantly different from the starting values of 7.1 and 7.2 (Table SI). Over the course of most of the simulation, subunit A exhibited a lowered average Cp pKa (6.84) whereas subunit B had an unshifted average pKa (8.05). The same asymmetry was observed in the second dimer simulation; this time, however, subunit A had an elevated average Cp pKa (7.87) compared to subunit B (6.86). Asymmetry appeared at about 5 ns and lasted until the end of the simulation (Figure 2C). At the end of the second simulation, backbone and side chain RMSDs between subunits A and B were 3.19 Å and 3.59 Å, and the Cp pKa values were 8.4 and 6.5, respectively, again, very different from initial conditions (Table SI).

These observations indicate that asymmetry develops between dimers during the simulations. It is worth noting that either subunit in a dimer can exhibit the lowered or unshifted pKa. This reflects the symmetric nature of the homodimeric structure. One might expect the nearly perfect symmetry in the x-ray structures to lead to identical Cp pKas, but the simulations indicate that there are asymmetric Cp pKas for each subunit in the dimer at any time. However, if the asymmetry can occur in either monomer, then when averaging over time, or multiple simulations, we hypothesize that the two subunits should exhibit identical Cp pKa.

To verify this hypothesis, eight more dimer simulations starting with the same initial structure but different initial velocity were performed, each lasting 12ns. The asymmetry is present in every simulation; the minimum average absolute value of Cp pKa difference between subunit A and B among all the simulations is 0.77 pK units (Table I). When summing over all ten dimer simulations, the average absolute difference becomes 0.98 ± 0.72 pK units. However, of all the dimer conformations being calculated, the average Cp pKa of subunit A and B are 7.63 and 7.68, respectively. For Cp pKa values of subunit A, 46.3% are greater than subunit B, and 50.7% are less than subunit B. So, as indicated by our hypothesis, on average, the two subunits exhibit no asymmetry at all within the homodimer.

Table I.

Results for ten dimer simulations

| <A-pKa> | <B-pKa> | Abs(Δ) | SD | (A>B)% | (A<B)% | (A=B)% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 1 | 7.31 | 6.76 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 70% | 27% | 3% |

| Trial 2 | 8.11 | 7.72 | 1.16 | 0.75 | 58% | 39% | 2.2% |

| Trial 3 | 7.63 | 7.68 | 0.77 | 0.55 | 48% | 47% | 4.2% |

| Trial 4 | 7.20 | 7.48 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 35% | 60% | 4.5% |

| Trial 5 | 7.68 | 8.22 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 25% | 70% | 4.8% |

| Trial 6 | 7.70 | 8.01 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 33% | 64% | 3.5% |

| Trial 7 | 7.03 | 7.48 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 26% | 71% | 3.5% |

| Trial 8 | 7.73 | 7.98 | 0.85 | 0.65 | 42% | 56% | 2.7% |

| Original1 | 6.84 | 8.07 | 1.29 | 0.68 | 6.3% | 93% | 1.1% |

| Original2 | 7.87 | 6.86 | 1.16 | 0.87 | 83% | 15% | 2.6% |

| Average | 7.51 | 7.57 | 0.97 |

The asymmetry developed in the dimer simulations might be inherently important for the function of typical 2-Cys Prxs. As a deprotonated Cp is required in the initial step of the Prx reaction cycle, the asymmetric Cp pKa values of the subunits suggest an asymmetric protonation state of the Cps in the dimer, with one subunit Cp predominantly protonated and the other subunit Cp largely deprotonated at physiological pH. It stands to reason, then, that the entire dimer should exhibit half-site reactivity, with one subunit being in an activated state at a time.

Conserved Pathways connecting the Cp of different subunits exist in the TryP dimer

The above results indicate that asymmetric Cp pKas are developed dynamically during dimer simulations. The following question is thus raised: how do the two subunits in the dimer communicate with each other, so that they possess asymmetric Cp pKas at any timepoint ? To answer this question, the correlation coefficients between Cp pKa difference and every residue’s backbone ϕ and ψ angle across all ten dimer simulations were calculated. A large number of residues were identified which have significant correlations with Cp pKa. The backbone fluctuations of these residues help to propagate the asymmetry of Cp pKa from subunit A to B. Starting with the Cp of subunit A, all the residues with heavy atoms within a certain cutoff distance and with a correlation above a certain cutoff correlation coefficient are identified. Then from each of these residues, all the residues with heavy atoms within the same cutoff distance and with the correlation above the same cutoff correlation coefficient are identified. This process is continued iteratively, until the Cp of subunit B is included in the list. The asymmetric Cp pKa is assumed to propagate from subunit A to B through the backbone fluctuation of these residues along the path.

Two distinct paths with the strictest cutoff conditions are identified. In the first path, the cutoff distance is 4.0 Å, and the cutoff correlation coefficient is 0.2. The residues along the pathway are, Cp(A), Y44(A), F43(A), F131(A), Q141(A), R140(A), L9(A), K120(B), V125(B), M78(B), S77(B), Y44(B), Cp(B) (Figure 3A). The letter in the parenthesis indicates the subunit this residue belongs to. In the second path, the cutoff distance is 3.5 Å, and the cutoff correlation coefficient is 0.15. The residues along the pathway are, Cp(A), Y44(A), F43(A), G129(A), T143(A), Q141(A), N145(B), V149(B), Cr(A), V172(A), M184(A), F50(B), Cp(B) (Figure 3B). It is worth noting that the resolving cysteine (Cr), another conserved cysteine involved in the reaction cycle, is in the second path. Almost all of these residues are strongly conserved in the typical 2-Cys Prx family of proteins (Table II, Figure SI).

Figure 3.

Cartoon diagram of pathways connecting the Cp of subunit A (blue) and subunit B (red). Cp from subunit A and B are shown as yellow Van der Waal spheres. Residues from the subunit A and B are shown as white and green Van der Waal spheres, respectively. (A) The cartoon diagram of the first pathway, the distance cutoff of this pathway is 4Å, and correlation coefficient cutoff is 0.2. (B) The cartoon diagram of the second pathway, the distance cutoff of this pathway is 3.5 Å, and the correlation coefficient cutoff is 0.15.

Table II.

Conservation of residues involved in the pathways in dimer simulations

| L9 | Not conserved; |

| F43 | Conserved in 2-Cys Prx; |

| Y44 | Conserved in 2-Cys Prx; |

| F50 | Conserved in 2-cys Prx; |

| S77 | Conserved in 2-Cys Prx; |

| M78 | I or M in TryP, V or M in PrxII, V or I in AhpC, V in Prx I, IV, III; |

| K120 | Conserved in Prx I, II; mutate to E in some TryP; |

| V125 | Conserved in TryP; |

| G129 | Conserved in Prx I, II, III, IV, TryP; |

| F131 | Conserved in TryP; |

| R140 | Conserved in Prx I, II, IV, TryP, and AhpC; mutate to K in some Prx III; |

| Q141 | Cconserved in Prx I, II, IV, TryP; mutate to H in some Prx III and AhpC; |

| T143 | Conserved in Prx I, II, IV, TryP; |

| N145 | Conserved in Prx I, II, III, IV, TryP; mutate to T in some AhpC; |

| V149 | Conserved in Prx I, II, III, IV, TryP; mutate to L and I in some AhpC; |

| V172 | Conserved in 2-Cys Prx; mutate to L in some AhpC; |

| Cr 173 | conserved in 2-Cys Prx; |

Asymmetric Cp pKa values in the TryP dimer originate from restricted conformational sampling

The monomer simulations suggest that the Cp pKa is unshifted compared to the pKa of an isolated cysteine. In contrast, the dimer simulations indicate the occurrence of one lowered Cp pKa in a dimer at a time. Considering the almost identical initial structures of the subunits, the effects of dimerization should be one of the most important explanations for the pKa asymmetry. In general, Cp pKas in the dimer could be lowered through two mechanisms, (1) one of the Cp pKas in the dimer is lowered by the additional Born term, background term and site-site interactions from the other subunit across B interface (static); or (2) relative to the monomeric form, dimerization restricts the conformational freedom of the subunits in the AB dimer, so that only active site conformations with lowered Cp pKa are accessible for one of the subunits (conformational).

To distinguish between these two possible mechanisms, all collected dimer structures from the first dimer simulation were separated into two monomers and the Cp pKa for each monomer was calculated individually. The calculated results are the pKas in the pure monomeric forms without electrostatic contributions from the additional B-type interface interactions (including Born term, background term and site-site interactions from the partner subunit). When compared with the full dimer results, which naturally includes the interactions from the additional B-type interface, the two calculations gave virtually identical results (Figure 4). The average Cp pKa differences (<pKa dimer - pKa monomer>) for subunits A and B are −0.03 and 0.14 pK units respectively. The simulations therefore suggest that the conformational mechanism is a preferred explanation for the pKa asymmetry, because the same pKa is calculated in presence or absence of the other subunit. In other words, the effects of dimerization across the B interface restrict the active site conformational sampling so that one of the two subunits in a dimer exhibits a lowered Cp pKa microenvironment.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the Cp side chain pKa during the first dimer simulation for isolated subunits A (A) and B (B). In both panels, Cp pKa calculated in the dimeric form are depicted in black and Cp pKa calculated in the monomeric form are depicted in gray. Note that these lines are virtually indistinguishable.

Lowered and modestly asymmetric Cp pKas in the TryP decamer suggest a high reactivity state for all subunits within the decamer

A simulation was conducted using the complete decameric form of TryP (10.6 ns). In the analysis of this simulation, the decamer was separated into five dimers exhibiting only the B-type interface and pKa calculations were performed on each. We do this because the decamer is too large to calculate all the site-site interactions between titratable residues.

In the decamer simulation (Figure S2), the average Cp pKa over the entire simulation and over all the subunits was 7.4. This value is lower than the average Cp pKas of the monomer simulations. It is also lower than the pKa of the “unshifted-Cp-pKa” subunits in the dimer simulations (Table III). Moreover, the average Cp pKas show obvious heterogeneity among subunits. For example, subunits C and D exhibited the highest average Cp pKas, around 7.8, while the average Cp pKa of subunit F was less than 7.0. For each dimer, the asymmetry of Cp pKas could still be observed but was more modest than observed in the dimer simulations (Table III). The results suggest that more than 50% of the subunits sample conformations in which the Cp pKa is lowered in the decamer. The decameric form of the enzyme would have more deprotonated Cps and, thus, a higher overall activity than either the monomeric or the dimeric forms. This is, in fact, supported by experimental evidence (18–20).

Table III.

Average Cp pKa in all MD simulations of 1uul.

| Subunit | Average Cp pKa | Standard deviation | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer Simulations | |||

| A | 8.64 | 0.58 | 0.02 |

| B | 8.01 | 0.59 | 0.02 |

| Dimer Simulations (First and Second) | |||

| First A | 6.84 | 0.45 | 0.01 |

| First B | 8.05 | 0.66 | 0.01 |

| Second A | 7.87 | 0.96 | 0.02 |

| Second B | 6.86 | 0.42 | 0.01 |

| Decamer Simulation | |||

| A | 7.58 | 0.62 | 0.01 |

| B | 7.21 | 0.42 | 0.01 |

| C | 7.84 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| D | 7.79 | 0.44 | 0.01 |

| E | 7.27 | 0.35 | 0.01 |

| F | 6.94 | 0.33 | 0.01 |

| G | 7.29 | 0.46 | 0.01 |

| H | 7.09 | 0.41 | 0.01 |

| I | 7.66 | 0.40 | 0.01 |

| J | 7.33 | 0.48 | 0.01 |

Structural origins of the pKa shift, background term and site-site interactions only

As described in the Methods, three factors are responsible for pKa shifts, the Born term, the background term and site-site interactions. Comparisons of the magnitude and the evolution of these factors among different simulations provide clues about how structural properties facilitate the Cp pKa shift in the different oligomeric states. The calculated Born terms of Cps were similar to each other and did not change significantly in the different simulations (results not shown). The almost constant Born terms suggest that the additional low dielectric region from the B-type protein interface in both dimer and decamer has little effect on the Cp pKa shift; therefore, in subsequent paragraphs, our focus is mostly on site-site interactions and the background terms.

For clarity, in the following paragraph, one prime is added after a residue number if it is from another subunit that forms a B-type interface with the subunit that contains the Cp of interest, and a double prime denotes a residue from another subunit that forms A-type interface with the subunit that contains the Cp of interest. For example, consider subunits A, B and C, in which dimer AB exhibits the B-type interface, thus, contains two fully functional active sites and BC forms the A-type interface. If Cp in subunit B is the Cp of interest, T49, T49′ and T49″ represents the T49 from subunits B, A and C, respectively.

Site-site interactions: T54 and E55 contacts at the B-type interface influence the Cp pKa shift in dimers and decamers

Site-site interactions are important in effecting a pKa shift, especially in the case of Prxs where the actual pKa is different from the intrinsic pKa (see Methods). Interactions between the Cp and all the other titratable residues were calculated for each simulation. It is noteworthy that the Prx Cp pKa is determined by a strong and large electrostatic interaction network. There are at least 23 titratable residues whose interaction energies with Cp are greater than 0.25 pK units at least occasionally during the simulations and 10 titratable residues whose interaction energies with Cp averaging over the simulations are around 0.5 pK units. The interactions of some residues (Y44, R128) are significant in every simulation (average value above 1.1 pK units), but show similar average values in all simulations. These residues are important to the functions of Prxs by directly shifting the Cp pKa from pKa of cysteine in the isolated forms, but they play little role in varying Cp pKa values in different oligomeric states. As a result, they are not discussed in this paper. In contrast, the effects of T49, T54 and E55 were unusual because the interaction energies between Cp and these residues not only have significant magnitude (average value greater than 0.5 pK units) but also show obvious heterogeneity among simulations (Table IV). All three of these residues are conserved throughout the typical 2-Cys Prx family (4) (Figure S1). Structural analyses provide insight into how these residues are involved in Cp pKa shift.

Table IV.

Average interaction energy between Cp and important residues in all MD simulations of 1uul

| Subunit | Thr49 | Thr54 | Glu55 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monomer Simulations | |||

| A | 1.2 | 0.36 | 0.67 |

| B | 1.13 | 0.36 | 0.64 |

| Dimer Simulations | |||

| First A | 2.09 | 0.76 | 1.24 |

| First B | 1.79 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| Second A | 1.97 | 0.74 | 1.07 |

| Second B | 2.25 | 0.71 | 0.96 |

| Decamer Simulation | |||

| A | 1.79 | 0.81 | 1.04 |

| B | 2.26 | 0.73 | 1.03 |

| C | 0.91 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| D | 0.88 | 0.72 | 0.92 |

| E | 2.43 | 0.73 | 1.08 |

| F | 2.47 | 0.75 | 1.04 |

| G | 2.33 | 0.70 | 0.98 |

| H | 2.40 | 0.76 | 0.94 |

| I | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.95 |

| J | 2.26 | 0.71 | 1.00 |

T54 and E55 have similar effects on the Cp pKa shift and are described together in this section. Their average interaction energies with Cp increase in magnitude in the dimer and decamer simulations compared to the monomer simulations (Table IV). Meanwhile, among subunits in the dimer and decamer simulations, the interaction energies between Cp and these two residues do not have considerable differences, no matter how different the subunits’ Cp pKas are. A closer look at these residue positions in structural space indicates how dimerization may affect these residues’ side chain positions in the different oligomeric states.

The T54 and E55 side chains are located at the B-type interface (Figure S4). In the dimer and decamer, steric contacts arise between these residues and A175′ of the neighboring subunit. During the simulation, the closest distance between the side chain of A175′ and that of T54 and E55 are measured at around 3.2 Å and 4.3 Å, respectively. The steric contacts across the B-type interface may force the side chains of these two residues to be restricted to positions closer to Cp. The average distances between Cp Sγ and T54 Oγ1 or E55 Cδ are decreased in the dimer simulations as compared to those in the monomer simulations (about 0.4 Å and 1 Å for T54 and E55, respectively) (Table SI). Consequently, the Cp interaction energies with T54 and E55 increase significantly in the dimer and the decamer simulations compared to the monomer simulations. At the same time, in the dimer and decamer simulations, the observation of essentially unvarying interaction energies with Cp among subunits is consistent with the almost identical average distances between the titratable atoms of T54, E55 and Sγ of Cp.

A175′ forms a steric contact with T54 and E55 across the B-type interface that seems to be crucial for maintaining the Cp pKa in dimer and decamer simulations. It is noteworthy that A175′ is one of the most conserved residues in the typical 2-Cys Prx family (4) (Figure S1). This is probably because its side chain size is crucial to maintaining the locations of T54 and E55 relative to Cp in the Prx B-type interface. From this observation, we would predict that if this residue was mutated to a residue with a smaller side chain (Gly), its contacts with T54 and E55 would likely be reduced or eliminated. The Prx B-type interface would then be more “monomer-like”, in which, as suggested by the monomer simulations, the TryP would have only low catalytic activity because of an unshifted pKa for Cp. On the other hand, if this residue was mutated to a larger residue, the steric contacts between this residue and T54, E55 would increase dramatically, likely breaking or distorting the B-type interface, and also reducing the catalytic activity.

Site-site interactions: position of the T49 side chain has a strong effect on pKa shifts in all oligomeric states

T49, within the TXXC motif conserved in Prxs (4) (Figure S1), has the highest interaction energy with Cp among all the titratable residues (Table IV). In addition, the evolution of the site-site interaction between T49 and the Cp is highly correlated with the Cp pKa in all simulations. The correlation coefficient between Cp pKa and interaction energy of T49 and Cp across all the simulations is −0.57, with low interaction energy correlating with high Cp pKas and vice versa. These results suggest that interaction between Cp and T49 is an important origin of the heterogeneity of Cp pKa in the different oligomeric states. A more detailed analysis of the Cp interaction energy with T49 and the local configuration around these residues is therefore warranted.

For all simulations, evolution of the site-site interaction between Cp and T49 indicate that there are three “states” of interaction energies (Figure 5), the lowest interaction energy with a magnitude around 0.9 pK units; the middle group with a magnitude around 1.5 pK units; and the group with the highest interaction energies exhibiting a magnitude around 2.5 pK units. The separation of the interaction energies into three states suggests that there might be three different local configurations for the T49-Cp region, and this is indeed found to be the case (Figure 6A).

Figure 5.

Evolution of the interaction energy between Cp and T49 in all simulations. In the monomer simulation (A), the first and the second dimer simulation (B) and (C), subunits A and B are depicted in black and green. In the decamer simulation, subunits C, D and I (D) are depicted in black, green and blue, subunits E, F, G and H (E) are depicted in black, green, blue and mauve, subunits A, B and J (F) are depicted in black, green and blue. Panel (G) is the hypothesized T49-Cp free energy landscape in monomer; panels (H) and (I) are the hypothesized T49-Cp free energy landscape in dimer for subunits with lowered Cp pKa and unshifted Cp pKa, respectively; panel (J) is the hypothesized T49-Cp free energy landscape in decamer.

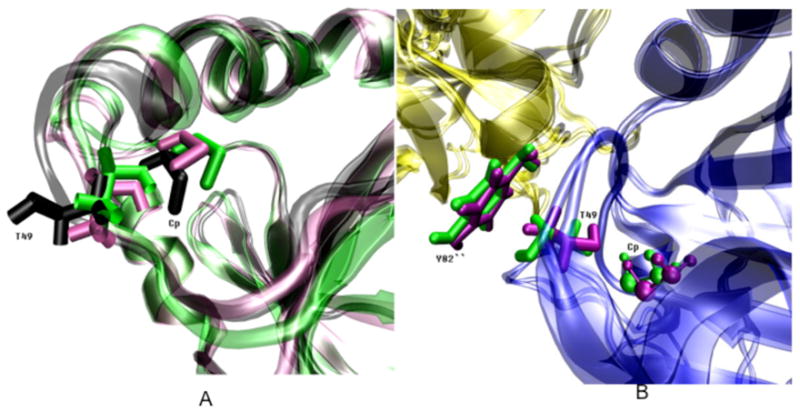

Figure 6.

(A) Cartoon diagram of the structural alignment between cluster representatives selected to represent the three interaction energy states between T49 and Cp illustrated in Figure 5. These three states correspond to three T49-Cp interaction energy configurations. The lowest interaction energy T49-Cp configuration is from subunit A the monomer simulation (black), the middle energy configuration is shown for subunit A from the first dimer simulations (green) and the highest energy structure is from subunit F in the decamer simulation (mauve).

(B) Structural alignment between the highest and the lowest energy conformations of T49 in the context of A-type interface. The subunit from the other dimer is in yellow. In the highest interaction energy conformation, the side chain of Cp (sphere), T49 (rod) and Y82″ from another dimer are in mauve. On the other hand, the side chain of Cp (sphere), T49 (rod) and Y82 from another dimer in the lowest interaction energy conformation are in green.

In the following paragraphs, these three conformations, corresponding to three site-site interactions, are referenced as interaction energy conformations. The major structural differences between the highest and the lowest interaction energy conformations are at the χ1 dihedral angle of T49, defined by N, Cα, Cβ and Oγ1. In the highest interaction energy conformation (light purple structure, Figure 6A), this dihedral angle of T49 is approximately 53.5° and the distance between T49 and Cp shows the closest proximity, about 3.2 Å between Sγ of Cp and Oγ1 of T49. In the lowest interaction energy conformation (black structure, Figure 6A), although the Cp and the backbone of T49 do not move significantly, the side chain of T49 flips out of the active site pocket, away from Cp, pointing towards the A-type interface (Figure 6B). The χ1 of T49 in this interaction energy conformation is approximately 170°. Accordingly, the distance between Sγ of Cp and Oγ1 of T49 in this interaction energy conformation increases to 5.8 Å. In the middle interaction energy conformation (green structure, Figure 6A), the χ1 of T49 mostly overlaps with its value in the highest interaction energy conformation, however, the distance between Sγ of Cp and Oγ1 of T49 in the middle interaction energy conformation is slightly longer than in the highest interaction energy conformation (about 4.6 Å). This longer distance is mainly caused by the χ1 dihedral angle change of Cp, defined by N, Cα, Cβ and Sγ. The Cp χ1 is approximate −60° in the highest and lowest and −170° in the middle interaction energy conformations.

At the beginning of each monomer simulation, the T49-Cp local configuration fluctuated between the two higher interaction energy conformations. Then, at about 4 ns, the local configuration shifted to the lowest interaction energy conformation in both monomer simulations and remained there until the end (Figure 5A). The results suggest that the lowest interaction energy conformation is the most favorable configuration (i.e. local minimum in the hypothesized T49-Cp free energy landscape, Figure 5G) when Prxs are in the monomer with no constraints from other subunits. The low interaction energy between T49 and Cp increase the Cp pKa, and hence, constitute one of the most important reasons for the unshifted Cp pKa in the monomer. The T49 side chain is not restrained by the dimer directly (as T54 and E55 are restrained by Ala175′, Figure S4) and thus, the T49-Cp configuration could sample the three interaction energy conformations freely. However, the lowest interaction energy conformation may no longer be the most favorable configuration in the dimer and decamer.

In the dimer simulation, the T49-Cp configuration shows the most volatility among the three oligomeric states with continually fluctuating interaction energies (Figure 5B, 5C). The T49-Cp configuration in the two subunits exhibiting low Cp pKa (subunits A and B in the first and second dimer simulations, respectively) only fluctuates between the two higher interaction energy conformations. The T49-Cp configuration in the two subunits exhibiting higher Cp pKa (subunits B and A in the first and second dimer simulations, respectively) can move between all of the three interaction energy conformations (Figure 5B, 5C). We hypothesize that the free energy barriers between three interaction energy conformations might be decreased by the B-type interface in some unknown way, so that the lowered Cp pKa of one of the two subunits favors the two high interaction energy conformations (Figure 5H), whereas for the unshifted Cp pKa subunits, the three interaction conformations are more or less equivalent to each other (Figure 5I).

In the decamer simulation, the T49-Cp in subunits C, D and I spent virtually the entire simulation time in the lowest interaction energy conformation (Figure 5D). Consequentially, the Cps of these subunits show the highest average pKas among all the subunits of the decamer. In subunits E, F, G and H, the T49-Cp configuration sampled predominately the highest interaction energy conformation (Figure 5E). The average Cp pKa of these subunits are the lowest among all the subunits. Cp in subunits A, B and J have the intermediate pKa values and T49-Cp conformations for these subunits spend at least some time sampling two of the three interaction energy conformations (Figure 5F). This heterogeneity of Cp pKas as well as the site-site interactions between T49 and Cp are most likely the result of the additional A-type interface introduced between dimers in the decamer.

As suggested by the dimer simulations, the B-type interface in the dimer decreases the free energy barrier between three T49-Cp interaction energy conformations. The presence of the A-type interface in the decamers, in addition, brings the Y82″ side chain in close proximity to the side chain of T49 when the T49-Cp configuration is in the lowest interaction energy conformation (Figure 6B). Y82 is conserved in most of the 2-Cys Prx family of proteins, but is replaced by phenylalanine in some cases (4) (Figure S1). The effect of Y82″, and hence the A-type interface, are twofold. On the one hand, the steric contact between T49 and Y82″ restricts the T49-Cp configuration, allowing it to sample only the two higher interaction conformations as in the cases of subunits E, F, G, H and J. On the other hand, once the T49-Cp configuration adopts the lowest interaction energy conformation, this same steric contact might also prevent the side chain of T49 from flipping back to the higher two interaction energy conformations, as with subunits C, D and I.

During the entire decamer simulation, the transformation between the higher and lowest interaction energy conformations only occurs once, in subunit B at around 9 ns (Figure 5F). The presence of the additional A-type interface in the decamer might increase the free energy barriers between the lowest and the two higher interaction energy conformations (Figure 5J), thus acting as a “door” separating the two higher from the lowest interaction energy conformation. As a result, both the two higher and the lowest interaction energy conformations are stable in the decamer, and are harder to interconvert than in dimer.

The effect of the background term correlates only with high Cp pKa subunits in the dimer

As mentioned before, the Born term and background term are used to determine the intrinsic pKa and, thus, should be important in determining the final pKa value. Since the Born term does not change significantly among the simulations (not shown), our focus is on the background term of Cp which exhibits large variability among all the simulations (Table V). In our Prx simulations, the lower the average value of the background terms, the lower the Cp pKa. The correlation coefficient between the background term and the Cp pKa in all simulations is 0.79. Given this correlation, we expected some conformational changes affecting the Cp pKa to be due to the background term.

Table V.

Average background term in all MD simulations of 1uul

| Subunit | Average background term |

|---|---|

| Monomer Simulations | |

| A | −0.18 |

| B | −0.42 |

| Dimer Simulations | |

| First A | −1.80 |

| First B | −1.11 |

| Second A | −1.39 |

| Second B | −1.60 |

| Decamer Simulation | |

| A | −1.24 |

| B | −1.80 |

| C | −1.17 |

| D | −1.31 |

| E | −1.81 |

| F | −1.76 |

| G | −1.47 |

| H | −1.60 |

| I | −1.39 |

| J | −1.64 |

The average values of the Cp background term in the monomer simulations are almost 1 pK unit higher than the comparable values in the dimer and decamer simulations (Table V). So, the presence of the B-type interface dramatically decreases the average value of the background term. Since the background term originates from the contribution of all initial charges, except the titratable atoms, the backbone motion of some residues close to Cp could shift the background term, which could cause the background term to show heterogeneity among subunits in the dimer and decamer.

To determine which backbone movements are responsible for the Cp background term shift, the correlation coefficient between every residue backbone ϕ and ψ angle’s sine value and the background term of Cp was calculated for all subunits in the first two dimer simulations. Residues with significant correlations were identified (Table VI). In subunits with lowered Cp pKa values (subunits A and B in the first and second dimer simulations, respectively), no ϕ angles correlate with the background term (range is −0.22 to – 0.18), nor do any ψ angles (range is −0.26 to −0.22), except for residue F48 of subunit B in the second dimer simulation with a correlation coefficient of −0.41. Things are different in subunits with unshifted Cp pKa (subunits B and A in the first and second dimer simulations, respectively). The backbone fluctuations of most residues still don’t correlate with the Cp background term, however, M46, D47 and F48 can be identified in each subunit as having the highest correlation coefficient (Table VI). These residues are close to the Cp (Figure S3) and the results are consistent across the first two dimer simulations.

Table VI.

Residues with significant correlations between backbone φ/ψ fluctuations and Cp background term in the dimer simulations

| Dimer simulation 1 | Dimer simulation 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subunit A | Subunit B | Subunit A | Subunit B | |

| ϕ | None | 46, −0.41 48, −0.43 |

46, −0.70 48, −0.71 |

None |

| ψ | None | 47, −0.49 | 47, −0.73 | 48, −0.41 |

The correlations suggest that the backbone fluctuations near the active site pocket from the unshifted Cp pKa subunits are in concert so that their overall effects change the value of the background term and, hence, raise the Cp pKa.

Conclusions

Although oligomerization is a common phenomenon, the reasons why many proteins oligomerize are not well understood. The analyses presented in this work suggest that oligomerization greatly affects the reactivity of Cp in the Prx protein TryP, with the highest per-subunit activities expected in the decameric form of this protein.

First of all, as the lowered Cp pKa represents the activated protein and the unshifted Cp pKa (~8.3) represents predominantly inactive protein at physiological pH, the monomeric form of Prxs should exhibit only low activity since Cp pKa is high and the protonated thiol form predominates. Interestingly, the dimeric form of TryP exhibits dynamic asymmetry associated with the Cp pKa. The dimer should therefore exhibit half-site reactivity, with only one subunit in a dimer in the appropriate protonation state at a given time. The appearance of a lowered Cp pKa in the dimeric form suggests that typical 2-Cys Prx are obligate dimers not only because a disulfide bond needs to be formed between subunits within a dimer, but also because the dimeric form supports a lowered Cp pKa in 2-Cys Prxs, conveying greater catalytic activity than in the monomeric form. While subunits within the dimer exhibit asymmetric Cp pKa values at each point in time, both subunits show symmetric Cp pKas on average. Which subunit will exhibit the lowered Cp pKa depends solely upon the initial conditions of the whole system, indicating a dynamic asymmetry. Lastly, all subunits in the decameric forms of TryP have a lowered Cp pKa compared to the monomeric forms. Accordingly, every Cp in the decameric forms has a higher probability of being deprotonated and thus, activated.

The structural analyses further indicate that decamerization or dimerization lowers the Cp pKa by inhibiting the conformational flexibility of the subunits, i.e., only particular local conformations can be adopted in the dimer or the decamer. In the monomer, with no constraint from oligomerization, the active site region surrounding Cp is characterized by (1) longer side chain distances between Cp and T54, E55 and (2) the lowest interaction energy conformation of T49-Cp configuration. These two features both decrease the Cp interaction energy with these titratable residues and result in the unshifted Cp pKa in the monomeric form.

In the dimer and decamer, the steric contacts between residues in the B-type interface force T54 and E55 to fluctuate in positions closer to Cp, and these effects apply equally to every subunit in the dimer and decamer. Hence, while T54 and E55 play an important role in distinguishing the monomeric active site conformation from the dimeric conformation, they are not responsible for determining which subunits in the dimer and the decamer exhibit a lowered Cp pKa. The B-interface in the dimer and the additional A-interface in the decamer change the free energy landscape of T49-Cp configuration so that the higher two T49-Cp interaction energy conformations are more favorable in the decameric and dimeric forms than in the monomeric form. The presence of the B-interface also significantly decreases the background term in the dimer and decamer but not in the monomer. In addition, the backbone dihedral fluctuations of M46, D47, and F48 appear to be responsible for significant background term shifts in the dimer which in turn determine the final value of Cp pKa. In summary, the overall effect of the side chain motion of T49 and the background term (the backbone of residues M46, D47 and F48) not only separate the monomeric active site conformation from the dimeric and decameric conformation, but they also determine which subunits in the dimer and decamer are activated with a decreased Cp pKa at any given time.

A large number of residues affect the Cp pKa of 1uul in different ways, so that Cp can have different pKa values in different oligomeric states. Some residues shift the Cp pKa through direct interactions; some residues constrain conformation of 1uul that would affect other residues, and some residues are involved in the communication pathway between Cp residues in different subunits of a dimer. Most of these residues are conserved throughout the entire typical 2-Cys Prxs (Figure S1). If any one of these residues is mutated, the reactivity of typical 2-Cys Prxs should be impaired. According to our analysis, a few residues are listed in Table VII as recommended candidates for mutation experiments (including the physical predictions). Only strongly conserved residues that are involved in the communication pathways are included in Table VII. Mutations expected to directly shift pKa or affect conformation and interface are straightforward, while more complex pathway disruptions imparted by mutations would also likely disrupt the packing. The pathway disruption would also be expected to decouple the two subunits, which might be difficult to measure. However, these mutations may affect kinetic rates or may be observable via NMR with different chemical shifts.

Table VII.

Recommended residues for mutagenesis experiments

| Residue | Predicted Physical Effect |

|---|---|

| T49, T54, E55, R128 | Directly shift pKa. |

| A175 | Affect intra-dimer interface. |

| Y82 | Affect inter-dimer interface. |

| M46, D47, F48 | Affect conformations, indirectly shift pKa. |

| Y44 | Disrupt pathway, directly shift pKa |

| F43, F50, S77, R140, V172 | Disrupt pathway. |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the NSF (MCB-0517343, to JSF). All the calculations were performed on Wake Forest University’s DEAC cluster. The DEAC cluster is supported by the WFU IS department, by the Associate Provost for Research. and by storage hardware awarded to Wake Forest University through an IBM SUR grant. Partial support from NIH RO1 GM050389 (LBP) is also acknowledged, as is partial support from NIH R01CA129373 (FRS) for development of the pathway analysis tool.

Footnotes

Supplementary data and figures dealing with detailed distances to the sulfur atom of the Cp, additional details on the decamer simulation and a sequence alignment of PRX proteins are available at no charge from the authors directly; the supplementary data can also be purchased from Adenine Press for US $50.00.

References

- 1.Link AJ, Robison K, Church GM. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1259–1313. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore RB, Mankad MV, Shriver SK, Mankad VN, Plishker GA. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18964–18968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chae HZ, Kim HJ, Kang SW, Rhee SG. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1999;45:101–112. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofmann B, Hecht HJ, Flohé L. Biol Chem. 2002;383:347–364. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veal E, Day A, Morgan B. Mol Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood ZA, Schroder E, Harris JR, Poole LB. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Science. 2003;300:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang SW, Rhee SG, Chang TS, Jeong W, Choi MH. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:571–578. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin DY, Jeang KT. Peroxiredoxins in cell signaling and HIV infection. In: Sen CK, Packer L, Baeuerle PA, editors. Antioxidant and Redox Regulation of Genes, p381–407. Academic Press; 2000. pp. 381–407. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forman HJ, Cadenas E. Oxidative Stress and Signal Transduction. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii J, Ikeda Y. Redox Rep. 2002;7:123–130. doi: 10.1179/135100002125000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO. The World Health Report. Geneva: World health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karplus PA. A structural survey of the Peroxiredoxins. In: Flohé L, Harris JR, editors. Peroxiredoxin systems. Springer; New York : 2007. pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirotsu S, Abe Y, Okada K, Nagahara N, Hori H, Nishino T, Hakoshima T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12333–12338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schröder E, Littlechild JA, Lebedev AA, Errington N, Vagin AA, Isupov MN. Structure. 2000;8:605–615. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alphey MS, Bond CS, Tetaud E, Fairlamb AH, Hunter WN. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:903–916. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Hantgan RR, Karplus PA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5493–5504. doi: 10.1021/bi012173m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parsonage D, Youngblood DS, Sarma GN, Wood ZA, Karplus PA, Poole LB. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10583–10592. doi: 10.1021/bi050448i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitano K, Niimura Y, Nishiyama Y, Miki K. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1999;126:313–319. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan R, Mande SC. Biochem J. 2001;354:209–215. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3540209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun GH, Jorge DMM, Ramos HP, Alves RM, da Silva VB, Giuliatti S, Sampaio SV, Taft CA, Silva Carlos HTP. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;25:347–346. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoon J, Park J, Jang S, Lee K, Shin S. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;25:505–516. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cordomí A, Ramon E, Garriga P, Perez JJ. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;25:573–588. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CYC, Chen YF, Wu C-H, Tsai HY. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:57–64. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao JH, Yang CT, Wu JW, Tsai WB, Lin H-Y, Fang HW, Ho Y, Liu HL. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:65–74. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macchion BN, Strömberg R, Nilsson L. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:163–174. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonavane UB, Ramadugu SK, Joshi RR. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:203–214. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehrnejad F, Chaparzadeh N. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2008;26:255–262. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2008.10507241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoon J, Jang S, Lee K, Shin S. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2009;27:259–270. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ilda D, Giovanni C, Alessandro D. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2009;27:307–318. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordomí A, Perez JJ. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2009;27:127–148. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bairagya HR, Mukhopadhyay BP, Sekar K. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2009;27:149–158. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2009;27:159–162. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pineyro MD, Pizarro JC, Lema F, Pritsch O, Cayota A, Bentley GA, Robello C. J Struct Biol. 2005;150:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HJ, Kang SW, Yang CH, Rhee SG, Ryu SE. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:400–406. doi: 10.1038/nsb0598-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi J, Choi S, Choi J, Cha MK, Kim IH, Shin W. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49478–49486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Echalier A, Trivelli X, Corbier C, Rouhier N, Walker O, Tsan P, Jacquot JP, Aubry A, Krimm I, Lancelin JM. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1755–1767. doi: 10.1021/bi048226s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarma GN, Nickel C, Rahlfs S, Fischer M, Becker K, Karplus PA. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1021–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J Comp Chem. 1983;2:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J Chem Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Gunsteren WF, Berendsen HJC. Mol Phys. 1977;34:1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalé L, Skeel R, Bhandarkar M, Brunner R, Gursoy A, Krawetz N, Phillips J, Shinozaki A, Varadarajan K, Schulten K. J Comput Phys. 1999;151:283–312. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murtagh F. The Computer Journal. 1983;26:354–359. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelley LA, Gardner SP, Sutcliffe MJ. Protein Eng. 1996;9:1063–1065. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.11.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knaggs MH, Salsbury FR, Edgell MH, Fetrow JS. Biophys J. 2006;92:2062–2078. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.081950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cantor CR, Schimmel PR. Biophysical Chemistry. Vol. 1. Freeman; San Francisco: 1980. p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bashford D. Frontiers Biosci. 2004;9:1082–1099. doi: 10.2741/1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bashford D. An object-oriented programming suite for electrostatic effects in biological molecules. In: Ishikawa Y, Odehoeft RR, Reynders JVW, Tholburn M, editors. Lecture notes in computer science, p233–240. Springer; New York: 1997. pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bashford D, Karplus M. J Phys Chem. 1991;95:9556–9561. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Antosiewicz J, McCammon JA, Gilson MK. J Mol Biol. 1994;238:415–436. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bashford D, Gerwert K. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:473–486. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91009-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antosiewicz J, McCammon JA, Gilson MK. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7819–7833. doi: 10.1021/bi9601565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacKerell AD, Jr, Bashford D, Bellott RL, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, III, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salsbury FR, Knutson ST, Poole LB, Fetrow JS. Protein Sci. 2008;17:299–312. doi: 10.1110/ps.073096508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nozaki Y, Tanford C. Methods Enzymol. 1967;11:715–734. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee MS, Salsbury FR, Brooks CL. Proteins. 2004;56:738–752. doi: 10.1002/prot.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mongan J, Case DA, McCammon JA. J Comp Chem. 2004;25:2038–2048. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.