Abstract

We report the inhibition of the Aquifex aeolicus IspH enzyme (LytB, (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl diphosphate reductase, EC 1.17.1.2) by a series of diphosphates and bisphosphonates. The most active species was an alkynyl diphosphate having an IC50 = 0.45 μM (Ki ~ 60 nM), which generated a very large change in the 9 GHz EPR spectrum of the reduced protein. Based on previous work on organometallic complexes, together with computational docking and quantum chemical calculations, we propose a model for alkyne inhibition involving π (or π/σ) “metallacycle” complex formation with the unique 4th Fe in the Fe4S4 cluster. Aromatic species had less activity and for these, we propose an inhibition model based on an electrostatic interaction with the active site E126. Overall, the results are of broad general interest since not only do they represent the first potent IspH inhibitors, they suggest a conceptually new approach to targeting other Fe4S4-cluster containing proteins that are of interest as drug and herbicide targets.

Introduction

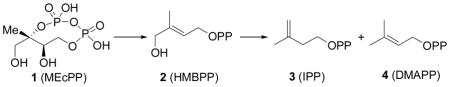

The Rohmer, methyl-D-erythritol phosphate or non-mevalonate pathway is responsible for isoprenoid biosynthesis in most pathogenic bacteria, as well as in malaria parasites.1, 2 Since isoprenoids are essential for survival in these organisms and since the non-mevalonate pathway is absent in humans, enzymes that comprise the pathway are important anti-infective drug targets3, 4 and in previous work 5, 6 it was shown that fosmidomycin (which inhibits the second enzyme in the pathway) gave very promising results in treating malaria. The structures and mechanisms of action of six of the eight enzymes present in the pathway have been known for some time, but deducing the structures (and mechanisms of action) of the last two enzymes has been more challenging. The penultimate enzyme is E-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl diphosphate (HMBPP) synthase (IspG, GcpE, EC1.17.7.1) which catalyzes the 2H+/2e− reduction of 2-C-methylerythritol-2,4-cyclo-diphosphate (MEcPP, 1) to HMBPP (2), while the terminal enzyme, HMBPP reductase (IspH, LytB, EC1.17.1.2) catalyzes the 2H+/2e− reduction of HMBPP to isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP, 3) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP, 4), in a ~5:1 ratio.

The structure of IspG has not yet been reported, but there have been two structures published for IspH, one from Aquifex aeolicus,7 the other from E. coli.8 Both structures contain Fe3S4 clusters. However, based on the results of Mössbauer9,10 and EPR spectroscopy,11 and from microchemical analyses,9, 11 we and others have concluded that Fe4S4 clusters are responsible for catalysis. The Fe4S4 cluster, while catalytically active, is thus relatively labile, as also found for example in aconitase and in pyruvate-formate lyase activating enzyme.12 To date, there has been only one report of IspH inhibitors,13 with IC50 values of ~1–2 mM having been obtained. Here, we report progress aimed at obtaining more potent inhibitors.

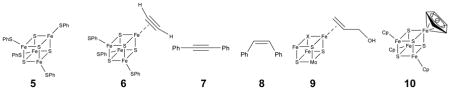

Based on the crystallographic, mutagenesis, catalytic activity and spectroscopic results described previously,7–11 we reasoned that there might be two distinct approaches to developing IspH inhibitors. In the first, it might be possible to develop “conventional” inhibitors which bind to amino-acids involved in catalysis. In previous work7 we proposed that a key residue involved in delivering H+ to HMBPP was the totally conserved E126, and the essential nature of this residue in catalysis has now been confirmed by site-directed mutagenesis.8 We reasoned that basic or cationic inhibitors might interact with this key residue, inhibiting the enzyme. The second hypothesis to test is that “unconventional” inhibitors, compounds that bind to the Fe/S cluster, might be developed. If the cluster is Fe3S4, this would be unprecedented and would thus, of course, not suggest what inhibitor structures to make. On the other hand, if the active species is Fe4S4 (as deduced from the IspH Mössbauer,9, 10 EPR11 and catalytic activity9, 11 results), there is in fact precedent for the formation of organometallic species (i.e. containing Fe-C bonds) between Fe4S4 clusters and alkynes, which would be expected to act as IspH inhibitors. For example, in the early literature, McMillan et al.14 investigated the reduction of acetylene (C2H2) to ethylene (C2H4) by reduced Fe4S4 synthetic clusters, in particular [Fe4S4(SPh)4]3−, 5. These workers proposed that an acetato complex reacted initially with C2H2 to form an organometallic species, 6:

most likely containing a side-on (π/σ) acetylene unit, which was then cis-reduced to ethylene. Basically the same reduction, of diphenylacetylene (7) to cis-stilbene (8), was reported by Itoh.15

In these systems, the alkyne complex was not observed directly, but under controlled potential (electrochemical reduction) conditions, Tanaka et al.16 found evidence for a π complex of acetylene bound to [Fe4S4(SPh)4]3− and [Mo2Fe6S8(SPh)9]3− clusters, as evidenced by quite large shifts in the C≡C vibrational Raman spectra. These workers also demonstrated that acetylene bound most strongly to reduced ([Fe4S4]+) clusters, and resulted in release of 1 SPh−. These results suggested to us that acetylenes might likewise bind to reduced IspH, forming organometallic (Fe-C) bonds. Interestingly, with low valent (FeI) complexes, alkynes have also been found to bind far more strongly than do alkenes,17 leading again to the possibility that alkynes could bind to Fe and be good IspH inhibitors, displacing the olefinic substrate, HMBPP.

This formation of a π (or π/σ) “metallacycle” complex would be very similar to that deduced for the binding of the HMBPP parent molecule, allyl alcohol (which lacks the Me and CH2OPP substituents) to the FeMo cofactor in nitrogenase,18 illustrated schematically above (9) as the Fe3MoS3X cubane-like fragment. It also seemed possible that aromatic residues might interact with the Fe4S4 cluster, just as the cyclopentadienide ion does in model Fe4S4 clusters,19 such as 10 (as an η6 as opposed to an η5 species). Although the structures of complexes such as 6 have not been confirmed crystallographically, the structure proposed by McMillan et al.14 (6) is likely to involve the same type of bonding as found in many other organometallic complexes,20 being described18 as a resonance hybrid of a pure π complex and a σ complex, the latter corresponding to a metallacycle.

Results and Discussion

In an effort to learn more about just what types of compound might bind to the Fe4S4 cluster in IspH, we first screened a series of small molecules, using EPR spectroscopy. The 9 GHz EPR spectrum of A. aeolicus IspH in the g ~ 2 region exhibits a broad spectrum (Figure 1a), very similar to that of the E. coli protein (Figure 1b) and is characteristic of an S=1/2 [Fe4S4]+species.11 The unliganded A. aeolicus IspH also has two small signals at g~5 (Supporting Information Figure S1a), which likely indicate the presence of higher spin species. For purpose of comparison, the g-values for the systems studied here are presented in Supporting Information Table S1, together with g-values for related systems such as aconitase, and IspG (GcpE).

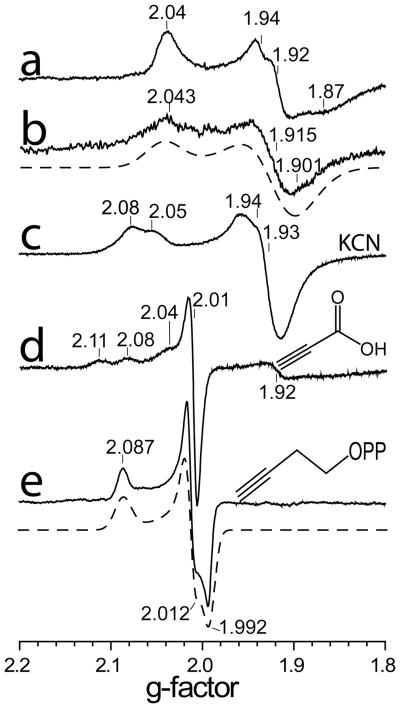

Figure 1.

9 GHz EPR spectra of IspH at 15K reduced with Na2S2O4. a) A. aeolicus IspH, no added ligands, microwave power = 1 mW. b) E. coli IspH, no added ligands, microwave power = 1 mW; c) A. aeolicus IspH + KCN, 10 equivalents, microwave power = 1 mW; d) A. aeolicus IspH + propiolic acid, 10 equivalents, microwave power = 0.2 mW; e) A. aeolicus IspH + but-3-ynyl diphosphate (12), 20 equivalents, microwave power = 0.05 mW. Spectral simulations are shown by the dashed lines (g-values are compiled in Supporting Table S1, together with g-values for Fe3S4 proteins).

We first tested a series of small molecules and ions: CO, N3−, MeCN and CN−, for cluster-binding in A. aeolicus IspH, but only CN− was found to have any effect on the EPR spectrum, Figure 1c (and Supporting Information Figure S1b). The g-values observed were 2.08/2.05 and 1.94, Figure 1c, close to those observed previously with CN− binding to the Pyrococcus furiosus 4Fe ferredoxin (g1 = 2.09, g2 = 1.95, and g3 = 1.92), another 4Fe-4S cluster with 3 Cys ligands and a unique 4th Fe position,21 due we propose to end-on binding to the 4th Fe in IspH. There was also an increase in signal intensity in the g~2 region (from ~20% to ~60% spin/protein), due to conversion of the higher spin state species to S=1/2.

We then tested a series of other small molecules that might be anticipated to bind in a sideways-on mode (as with proposed for acetylene in the model systems): propargyl alcohol, propargylamine and propiolic acid. All species resulted in large spectral changes, and by way of example the IspH + propiolic acid (HC≡CCO2H) spectrum is shown in Figure 1d. These results indicated to us that, as with the Fe4S4 containing small molecules, acetylenes bind to IspH, forming π or π/σ complexes. With both CN- as well as propiolic acid binding there also appear to be two bound ligand conformations or binding modes (e.g. hydrogen bonded or not), asevidenced by the splitting of the g1 signals.

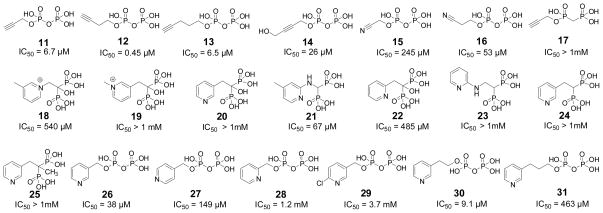

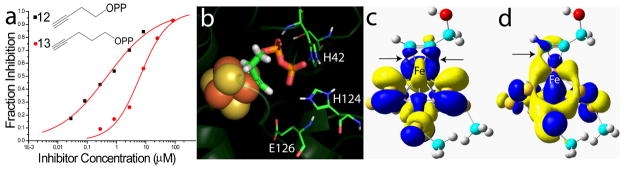

However, propiolic acid had poor activity in IspH inhibition, and we reasoned that acetylenic diphosphates (or the isoelectronic, cyano diphosphates) might interact more strongly with IspH, since there would be an increase in binding affinity due to their diphosphate moieties docking into the (inorganic) PPi site seen crystallographically.8 We thus synthesized four acetylenic diphosphates (11–14, Figure 2) and two cyanoalkyl diphosphates (15, 16) and tested them for their activity in IspH inhibition. IC50 results are shown in Figure 2. The most active compound was 12 with an IC50 = 0.45 μM (Ki ~ 60 nM; Figure 3a). As shown in Figure 3b, this compound can bind with its diphosphate group in the inorganic “PPi” site seen crystallographically,8 with the alkyne fragment interacting with the unique 4th Fe (identified from EPR, Mössbauer and catalytic activity results, and added computationally here as described previously7), with Fe-C bond lengths of ~2.4 Å, suggesting π-complex formation. There was a large change in the EPR spectrum of IspH in the presence of 12 (Figure 1e, Supporting Information Figure S1c) indicating a major change in the cluster’s electronic structure, consistent with these docking results. Moreover, there was evidence for only a single bound species. The shorter chain analog 11 was less active than was 12, as was the longer chain analog 13, and conversion of the bridging O to CH2 (17) reduced the activity of 11 even more (Figure 2), due presumably to a disruption in H-bonding to the SXN motif. Likewise, the addition of a terminal CH2OH (14) reduced activity, consistent with the known stronger binding of terminal versus substituted alkynes to low valent Fe complexes.17 The changes in g-values on addition of the acetylenes were generally similar, as expected, and as with CN− there was a ~3× increase in signal intensity in the g~2 region (due to a high-to-low spin state conversion). We also tested the effects of the isoelectronic analogs (15, 16) of the acetylenes (-C≡C-H → -C≡N), cyanides, on IspH inhibition, but both compounds were far less active than their acetylenic counterparts.

Figure 2.

Structures of the 21 compounds investigated as A. aeolicus IspH inhibitors together with (below the structures) their IC50 values.

Figure 3.

IspH inhibition by alkyne diphosphates. a) Dose-response curves for IspH inhibition by 12 (IC50 = 450 nM) and 13 (IC50 = 6.5 μM). b) Proposed docking model for 12 bound to the IspH active site: the diphosphate binds to the PPi site while the alkyne group forms a π (or π/σ) “metallacycle” complex with the unique 4th Fe in the Fe4S4 cluster, similar to that proposed for acetylene binding to model Fe4S4 clusters and allyl alcohol binding to a nitrogenase FeMo cofactor. c) αHOMO-1 for propargyl alcohol bound to a model Fe4S4 cluster, illustrating metal ligand interaction. d) as c) but βHOMO-1. The contour values are ± 0.02 au.

These results clearly indicate that alkyne diphosphates can be good IspH inhibitors, with the most active species being > 1,000 × more potent than previously reported IspH inhibitors.13 Since PPi itself and other diphosphates are only weak (~1 mM) IspH inhibitors,8 we conclude that ligand binding is driven by π (or π/σ) or η2-alkynyl complex formation with the Fe4S4 cluster, the same type of complex formation as suggested by Raman spectroscopy,16 for acetylene binding to an [Fe4S4(SPh)4]3− cluster. Moreover, the results of density functional theory calculations show that there is indeed Fe-C metal ligand bonding present in an [Fe4S4(SMe)3(HC≡CCH2OH)]2− model system. We show in Figures 3c,d some typical MO results. The αHOMO-1 shows the interaction of an Fe d orbital with the C≡C π orbital, in the plane of the Fe…C≡C fragment. The βHOMO-1 illustrates the interaction between an Fe d orbital with another type of C≡C π orbital, this time perpendicular to the plane of Fe…C≡C. If IspH, under these reducing conditions, contained an Fe3S4 cluster, there would be no obvious way in which acetylenes would bind tightly to the cluster (or the protein), while η2-alkynyl (i.e. π or π/σ) complex formation is predicted, based on previous work, and is supported by the DFT results.

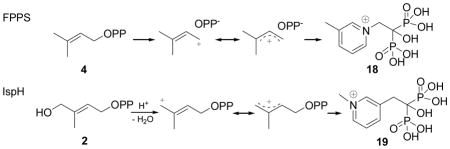

We next investigated a series of cationic (or basic) diphosphates and (cationic) bisphosphonates, which are isosteres of the diphosphate group. In previous work22 we found that aromatic, cationic bisphosphonates (such as 18) were potent (Ki ~ 20 nM) inhibitors of the enzyme farnesyl diphosphate synthase since, as shown below:

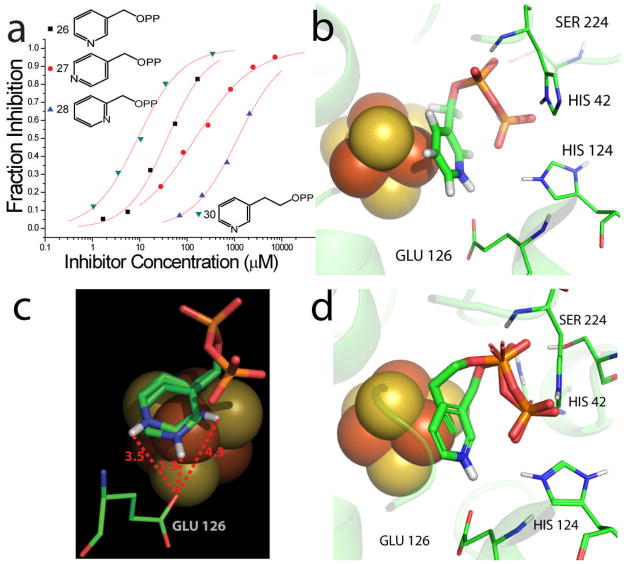

their charge distribution mimics that expected for the allylic cation/diphosphate anion ion-pair.23 In the case of IspH, similar allylic cations (shown above) have been proposed24 to be involved in catalysis, so we tested both 18 and 19 for their activities in IspH inhibition. Neither had potent activity (18, IC50 = 540 μM; 19, IC50 > 1mM, Figure 2). We then tested six additional bisphosphonates (20–25, Figure 2) with 1-H, 1-Me or 1-OH backbone groups and pyridine, pyridinium or amino-pyridine side-chains. The most active compound (IC50 = 67 μM) was 21, an amino-pyridine, expected to contain an amidinium-like (protonated) side-chain. Overall, however, the activity of these bisphosphonates was only modest, and based on Glide docking results using the “closed” IspH structure (PDB File #3F7T) it appeared that this might be due to the “branched” nature of the bisphosphonate backbone. We thus next synthesized a series of pyridinium diphosphates, 26–29, which based on computational docking results using Glide25 appeared to better fit the IspH active site. The most active compound in the series (Figures 2, 4a) was 26, a meta pyridinium diphosphate having an IC50 = 38 μM, slightly more potent than the best bisphosphonate, 21. When docked into the IspH active site, we find (Figures 4b, c) that when the diphosphate backbone binds to the “PPi” site seen crystallographically, the pyridinium HN is only ~1.9 Å from the E126 O (modeled as CO2-), indicating the possibility of an H-bond or electrostatic interaction with this active site residue. The para-pyridinium analog (27) was less active (IC50 = 149 μM), and the ortho-pyridinium analog (28) was far less active (IC50 = 1.2 mM), correlating with the increased NH-O (CO2−) distances of 3.47 Å and 4.28 Å, Figure 4c. Interestingly, all three aromatic rings also locate close to the 4th Fe, but the major decrease in activity seen as the ring nitrogens move away from the E126 carboxyl indicates the dominance of a Coulombic interaction, consistent with the lack of activity of the chloropyridine analog, 29, which is expected to be far less basic than is 26. These activity and docking results are consistent, then, with the pyridinium diphosphates binding to IspH with their PPi groups binding to the inorganic PPi site, while their aromatic rings interact with E126, as illustrated in Figures 4b, c. There was no major change in the EPR spectrum of 26 bound to the protein, Supporting Information Figure S1d, consistent with the lack of any π-complex interaction. We then sought to improve activity by varying the length of the CH2 spacer in the side-chain: addition of 1 CH2 group (30) resulted in an IC50 = 9.1 μM (Ki ~ 1.2 μM), but addition of 2 CH2 groups reduced activity (31, IC50 = 463 μM; Figure 2), with the pyridinium nitrogen in 30 again docking close to E126, while 31 did not. Taken together, these results argue against formation of a carbocation mechanism since for this, we would anticipate good activity for 28 (with maximum charge density separated by two carbons from the PPi backbone), while experimentally, maximum activity is found with 30 (with its NH+ located four carbons from the PPi backbone). That is, none of the cationic (18, 19) or pyridine/pyridinium analogs of the putative carbocation transition states (or reactive intermediates) act as inhibitors, while the longer chain species that can bind to both the PPi site as well as E126, are the most potent inhibitors among the whole series of compounds (18–31) investigated. Notably, with both the alkyne as well as the cationic inhibitors, the side-chains are located (Figure 4d) close to the Fe4S4 cluster blocking, we propose, HMBPP access.

Figure 4.

IspH inhibition by pyridinium diphosphates. a) Dose-response curves for IspH inhibition by 26, 27, 28 and 30. The IC50 for the most potent inhibitor (30) is IC50 = 9.1 μM; Ki ~ 1.2 μM. b) Glide docking pose for 26 bound to the IspH active site: the diphosphate binds to the PPi site while the pyridinium sidechain interacts with E126. c) View of the ortho, meta and para-pyridinium diphosphates (26–28) docked to IspH: the most potent inhibitor has the shortest HN…E126 CO2− distance; the worst inhibitor has the longest distance. d) Superimposed docking poses for 12 and 26 showing that they both bind in the same region (preventing HMBPP binding).

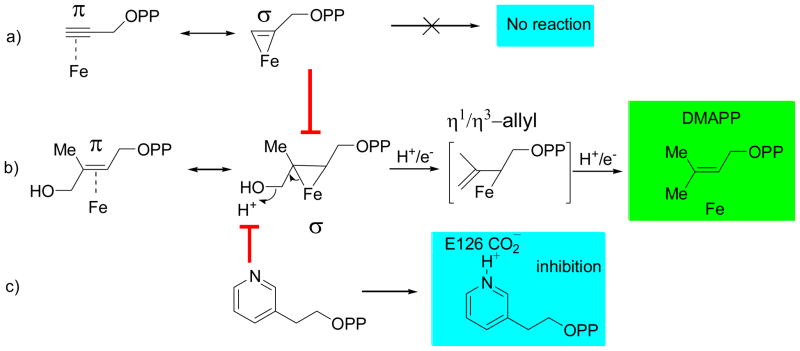

These results lead to the proposals for IspH inhibition shown in Figure 5. We propose that both alkyne as well as alkene diphosphates (i.e. HMBPP) bind to the Fe4S4 cluster at the unique 4th Fe, forming π (or π/σ) “metallacycles”, as shown in Figures 5a, b, the same type of binding reported previously for the HMBPP parent molecule (allyl alcohol) bound to the FeMo cofactor in nitrogenase.18 As shown in Figure 5b, the presence of such a metallacycle also immediately leads to a proposal for the IspH catalytic mechanism in which in a first H+/e− step, the HMBPP 4-OH is protonated and an η1-allyl intermediate and water form. This intermediate is then cleaved in a second H+/e- step, forming the DMAPP product, Figure 5b. IPP forms in the same way, after an η1-allyl (or η3-allyl) isomerization. This model is described in more detail elsewhere26 and is supported by electron nuclear double resonance spectroscopy using [u-13C] and [2H]-labeled HMBPP, which strongly suggest metal-ligand interaction. We thus propose that the alkyne as well as the cationic inhibitors block or displace HMBPP from binding to the Fe4S4 cluster: the alkynes form π (or π/σ) “η2-alkynyl” metallacycles, while the cationic inhibitors interact with the active site E126 carboxylate, again effectively blocking HMBPP binding.

Figure 5.

Mechanistic proposals for IspH catalysis and inhibition. a) π (or π/σ) metallacycle complex formation by alkyne inhibitors. b) IspH catalysis is which an η2-alkenyl metallacycle is reduced and protonated then dehydrates to form an allyl complex, which is then cleaved to form the DMAPP and IPP products. c) IspH inhibition by pyridinium diphosphates which block HMBPP binding to the 4th Fe.

Validation of the Mechanism of IspH Inhibition, and Catalysis

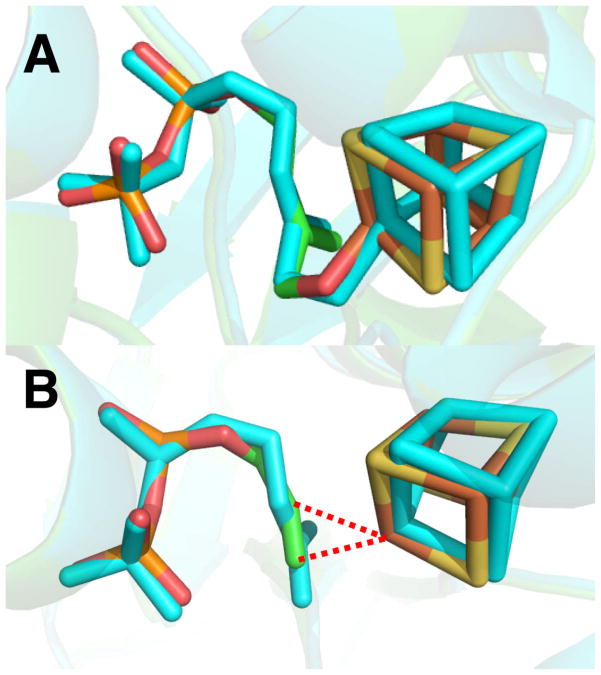

Finally, after review of this article, Grawert et al.27 reported the results of new crystallographic structures of HMBPP, PPi, IPP and DMAPP bound to IspH27 which help us validate the inhibition models proposed here. These workers now report that HMBPP binds as an alkoxide to the unique 4th iron (to the oxidized [Fe4S4]2+ cluster), the same binding mechanism we proposed earlier.7 On irradiation in the x-ray beam, HMBPP is reduced, forming a deoxy species (bound to the Fe4S4 cluster), basically as we proposed based on EPR/ENDOR and docking results.26 These x-ray results are of interest since they enable us to make a direct comparison between the x-ray and EPR/ENDOR/docking based methods,26, 27 helping us validate the use of inhibitor docking. We show in Figure 6a an alignment of the x-ray structure of HMBPP bound to IspH with that we proposed (Figure 1G in ref 26) for the initial HMBPP binding pose in which the O-4 can interact with the unique 4th Fe. There is a 0.32 Å rmsd between the heavy atoms (C, O, P) in the HMBPP ligand between the x-ray and our docking/EPR based structures, ~ 0.43 Å if we include the Fe, S atoms in the cluster, Figure 6a. On reduction, we proposed26 that the 4-OH is removed from the ligand and the σ/π metallacycle is reduced, resulting in loss of water and formation of a η1/η3-allyl complexes and thence, IPP and DMAPP.

Figure 6.

Comparisons between x-ray structures and docking/EPR/ENDOR deduced structures for a), HMBPP initial docking (PDB code 3KE8 and Ref. 25, Fig 1G). b) propargyl diphosphate (docking) superimposed on deoxy complex (PDB ID code 3KE9 and Ref. 25, Fig. 5).

The new crystallographic results are thus in good accord with those we proposed from our EPR, ENDOR and computational work, which gives confidence in the proposed ligand geometries we describe here for the bound inhibitors. As can be seen in Figure 6b, the alkyne group in propargyl diphosphate (11) bound to IspH26 is located in essentially the same position as the deoxy product species seen crystallographocally, where it can interact with the unique, 4th iron, forming a π or π/σ complex. The alkynes are much stronger inhibitors of IspH than are the alkenes (IPP, DMAPP),8 and indeed the ENDOR spectrum of 11 bound to IspH exhibits an ~6 MHz 13C hyperfine interaction,26 2–3 times larger than the 13C hyperfine interactions found for either allyl alcohol bound to nitrogenase,28 or HMBPP bound to IspH.26

Conclusions

Taken together, these results are of interest for several reasons. First, we find that cationic diphosphates are IspH inhibitors. However, rather than mimicking transition states/reactive intermediates, we propose that they interact with the active site E126, preventing HMBPP binding to the Fe4S4 cluster. Second, we find that alkyne diphosphates are quite potent (IC50 ~ 0.45 μM; Ki ~ 60 nM) IspH inhibitors. This activity was predicted based on previous Raman and catalytic activity results with model systems, which have been interpreted as indicating π (or π/σ) “metallacycle” formation between Fe4S4 clusters and acetylene. That alkynes are, in fact, IspH inhibitors, also supports the idea that catalytically active IspH contains active-site Fe4S4 and not Fe3S4 clusters, since there is no obvious way in which an alkyne group would bind to the three exposed S2− in such clusters. On the other hand, there is good literature precedent for alkynes binding to Fe4S4 clusters, supporting formation in IspH of π (or π/σ) complex formation. Third, the results of quantum chemical calculations indicate Fe-C metal ligand bonding with the acetylene group (in a [Fe4S4(SMe)3(HC≡CCH2OH)]2− model. Fourth, the formation of acetylene metallacycles is consistent with the observation that the HMBPP parent molecule, allyl alcohol, forms a metallacycle with the nitrogenase FeMo cofactor, which contains a related Fe/S (Mo, “X”) cluster and where the ligand forms Fe – C bonds with a single Fe. The observation that the IC50 for the most potent IspH alkyne inhibitor (IC50 = 0.45 μM; Ki ~ 60 nM) is much smaller than the KM for HMBPP binding (KM = 5 μM) is also expected based on organometallic precedent in which alkynes bind much more strongly (to low valent Fe complexes) than do alkenes.17 Fifth, we find that CN− binds to IspH with the resulting spectrum quite strongly resembling that found with P. furiosus Fd, another protein with an unique 4th Fe. And finally, the recent revision of the earlier 3 Fe IspH structural/mechanistic models is in accord with our earlier mechanistic proposal of initial binding of the HMBPP 4-OH (as an alkoxide) to an [Fe4S4]2+ cluster which, on reduction, forms an allyl complex which is then cleaved to form the IPP and DMAPP products.26 This gives confidence in the models we propose here for alkyne inhibition. These results also open up the intriguing possibility that metallacycle complexes may act as reactive intermediates (or transition states) in both IspG as well as IspH catalysis, and that alkynes can be expected to be good inhibitors of other Fe4S4 cluster-containing enzymes which contains “unique” 4th Fe atoms.

Materials and Methods

A. aeolicus IspH protein purification

BL-21(DE3) cells expressing IspH from A. aeolicus were grown in LB media supplemented with 150 mg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C until the OD600 reached 0.6. Cells were then induced with 200 μg/L anhydrotetracycline, then grown at 20 °C for 15 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (9000 rpm, 8 min, 4 °C) and were kept at −80 °C until use. Cell pellets were resuspended and lysed in B-PER(Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) protein extraction reagent for one hour at 4°C, then centrifuged at 200,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was applied to a Ni-NTA column equilibrated with 5 mM imidazole in pH 8.0 buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl and 150 mM NaCl. After washing with 20 mM imidazole, protein was eluted with 100 mM imidazole. Fractions were collected and dialyzed in pH 8.0 buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT, 4 times. The purified protein was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

E. coli IspH Protein Purification

BL21 DE3 (Invitrogen) cells harboring an E. coli IspH construct were grown in LB media at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.6. Induction was performed with 200 ng/ml anhydrotetracycline at 20°C for 15 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 9000 rpm for 8 mins and stored at −80 °C. Cell pellets were resuspended and lysed in B-PER (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) protein extraction reagent for about one hour at 4°C, then the lysate was centrifuged at 250,000 rpm for 30 mins. The supernatant was collected and loaded onto an IBA Strep-tag column equilibrated with buffer W (100 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). After washing with buffer W, protein was eluted using buffer E (buffer W containing 2.5 mM desthiobiotin). Fractions were collected and dialyzed in pH 8.0 buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 1mM DTT, twice. The purified protein was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Protein reconstitution

Both A. aeolicus and E. coli IspH proteins as isolated had a very small peak at 410 nm (A280/A410 < 0.02), so were reconstituted for further studies. Before reconstitution, protein was transferred into a Coy Vinyl Anaerobic Chamber after being degassed on a Schlenk line. The following steps were performed inside the anaerobic chamber with an oxygen level < 2 ppm. In a typical reconstitution experiment, 10 mM DTT and ~ 0.5 mg of elemental sulfur were added to 3 mL 0.6 mM protein solution in a pH 8.0 buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl and 5% glycerol. After stirring for 1.5 hours, FeCl3 was slowly added from a 30 mM stock solution to 6 equivalents. After 3 hours, an aliquot of the solution was centrifuged and a UV-VIS spectrum recorded. If the A410nm/A280nm ratio was ≥ 0.38, the protein was then desalted by passing through a PD10 column. If the ratio was < 0.38, more DTT, elemental sulfur and FeCl3 were added and the sample incubated with stirring (for typically ~ 2 hours) until the 410 nm/280 nm absorption ratio was ~ 0.38. The reconstituted protein was then concentrated by ultrafiltration, and the protein concentration determined by using a Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Protein Assay kit.

Enzyme inhibition assays

All assays were performed anaerobically at room temperature according to Altincicek et. al.24 with minor modification. To a pH 8.0 buffer solution containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 5% glycerol, sodium dithionite was added to 0.4 mM, methyl viologen was added to 2 mM, and IspH was added to 72 nM. For enzyme assays, various amounts HMBPP were added and the reactions were monitored at 732 nm. The initial velocities were fitted by using the Michaelis-Menten equation with OriginPro 8 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA) software. The activity of reconstituted A. aeolicus IspH tested under the conditions described above was 1.2 μmol min−1 mg−1 with a KM=7 μM. For inhibition assays, various concentrations of inhibitor were added and incubated for 10 min, prior to addition of 34 μM HMBPP. Initial velocities at different inhibitor concentrations were then plotted as dose-response curves, and were fitted to the following equation, from which IC50 values were determined:

where x is the inhibitor concentration and y is the fraction inhibition. Ki values were then deduced from the IC50 value by using the Cheng-Prusoff equation:29

where [S] is the HMBPP concentration, and KM is the Michaelis constant.

EPR spectroscopy

Samples for EPR spectroscopy were typically 0.3 mM in IspH, and were reduced by adding 20 equivalents of sodium dithionite followed by incubating for 5 min. Glycerol was added to 42.5 % (v/v). EPR samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen after reduction. EPR spectra were collected at X-band using a Varian E-122 spectrometer together with an Air Products (Allentown, PA) helium cryostat. Data acquisition parameters were typically: field center = 3250 G; field sweep = 800 G; modulation = 100 kHz; modulation amplitude = 5 G; time constant = 32 ms; 60 sec per scan; 8 sec between each scan; and temperature = 15K. EPR spectral simulations were carried out by using the EasySpin program.30

Docking calculations

For docking calculations, the IspH target protein (PDB: 3F7T) was prepared using the protein preparation wizard in Maestro 8.0.31 Water from the active site region was removed, as was the diphosphate ligand. The Fe3S4 cluster was reconstituted computationally to form the Fe4S4 species as described previously7 and hydrogen atoms were added to the protein. Hydrogen bonds were optimized to default values and an energy minimization in Macro-Model 9.532 performed only on the protein hydrogens, using default parameters. A receptor grid large enough to encompass all crystallographically-observed binding sites was then generated from the prepared target protein. Geometry optimized ligands were docked using Glide25 extra-precision (XP) mode, and no other constraints were applied. In some instances, we also used the MMFF94 force-field33 to effect further geometry optimization.

Density functional theory calculations

In order to gain a better understanding of the interaction between the propargyl diphosphate inhibitors and the Fe-S cluster, we used the published structure of the lowest energy form of allyl alcohol bound to the nitrogenase FeMo cofactor (structure 3 in ref.18), converting Mo → Fe, X→ S and allyl → alkynyl as the initial structure. Geometry optimization was performed by using the pure density functional theory (DFT) method with a BPW91 functional,34, 35 a Wachter’s basis (62111111/3311111/3111) for Fe,36 6-311G* for all the other heavy atoms, and 6-31G* for the hydrogens, using the Gaussian 09 program.37 This method is similar to that used in the calculations of the ligand-bound nitrogenase structures18 and is the same as that we used previously to make accurate predictions of NMR hyperfine shifts, ESR hyperfine couplings, as well as Mössbauer quadrupole splittings and isomer shifts, in various iron-containing proteins and model systems.38–43

Synthetic aspects

General methods

All reagents used were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). The purities of all compounds investigated were confirmed either via combustion analysis (for solid samples) or by using 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy at 400 or 500 MHz on Varian (Palo Alto, CA) Unity spectrometers. Cellulose TLC plates were visualized by using iodine or a sulfosalicylic acid-ferric chloride stain.44 Propargyl methanesulfonate and but-3-ynyl methanesulfonate were synthesized according to a literature method.45, 46 The syntheses and characterization of compounds 18–25 have been described previously.22, 47–51 and the samples used here were from the same batches as described.

General procedure for preparation of diphosphates

Diphosphates were prepared using modified literature procedures.52 Typically, 0.5–1 mmol of halide or mesylate in a minimum amount of CH3CN (0.4–0.6 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 2–3 equiv of tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3–6 mL) at 0°C, then the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 2–24 h at room temperature and solvent removed under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in cation-exchange buffer (49:1 (v/v) 25mM NH4HCO3/2-propanol) and slowly passed over 60–100 mequiv Dowex AG50W-X8 (100–200 mesh, ammonium form) cation-exchange resin, pre-equilibrated with two column volumes of the same buffer. The product was eluted with two column volumes of the same buffer, flash frozen, then lyophilized. The resulting powder was dissolved in 50 mM NH4HCO3. 2-Propanol/CH3CN (1: l (v/v)) was added, and the mixture vortexed, then centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm. The supernatant was decanted. This procedure was repeated three times, and the supernatants were combined. After removal of the solvent, lyophilization, then flash chromatography on a cellulose column, a white solid was obtained.

Synthesis of individual compounds

Prop-2-ynyl diphosphate (11)

Propargyl methanesulfonate (134 mg, 1 mmol) in CH3CN (0.5 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 2.70 g (3.0 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL) at −20°C. The reaction mixture was then slowly warmed to room temperature over 2 h and solvent removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (4:1:2.4 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 47 mg (18 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 2.68 (s, 1H), 4.38 (d, J H,P = 9.2 Hz, 2H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O) δ −10.10 (d, J= 20.7 Hz), −7.67 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

But-3-ynyl diphosphate (12)

But-3-ynyl methanesulfonate (148 mg, 1 mmol) in CH3CN (0.5 mL) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of 2.70 g (3.0 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL) at 0°C. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature over 24 h and solvent removed under reduced pressure. Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 28 mg (10%) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 2.16–2.17 (m, 1H), 2.35–2.40 (m, 2H), 3.81–3.84 (m, 2H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.83 (d, J = 17.0 Hz), −7.82 (d, J = 15.9 Hz).

Pent-4-ynyl diphosphate (13)

Pent-4-ynyl methanesulfonate (162 mg, 1 mmol) was treated with 2.70 g (3 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 103 mg (35%) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 1.65–1.70 (m, 2H), 2.13–2.17 (m, 3H), 3.83 (q, J = 6.8Hz, 2H). 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.64 (d, J = 20.9 Hz), −7.76 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

4-Hydroxybut-2-ynyl diphosphate (14)

4-Chlorobut-2-yn-1-ol (104 mg, 1 mmol) was treated with 2.70g (3 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.07(s, 2H), 4.31(d, J H,P = 6.8Hz, 2H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −10.11(d, J = 20.8 Hz), −8.85 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

Cyanomethyl diphosphate (15)

2-Chloroacetonitrile (76 mg, 1 mmol) was treated with 2.70 g (3 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 45 mg (17%) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.56 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 2H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −10.25 (d, J = 22.0 Hz), −7.37 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

2-Cyanoethyl diphosphate (16)

3-Bromopropanenitrile (134 mg, 1 mmol) was treated with 1.80 g (2 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (4 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 31 mg (11 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 2.68 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 3.96 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H). 31P NMR(162 MHz, D2O): δ −10.24 (d, J = 20.7 Hz), −6.21 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

[[(Prop-2-ynyl) phosphinyl] methyl] phosphonic acid (17)

Propargyl methanesulfonate (134 mg, 1 mmol) was treated with 2.70 g (3 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen methanediphosphonate in CH3CN (4 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 93 mg (35 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 2.00 (t, JH,P = 12.0 Hz, 2H), 2.70 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (dd, JH,P = 9.2 Hz, J = 2.0 Hz, 2H); 31P NMR (202 MHz, D2O): δ 15.59 (d, J = 9.3 Hz), 20.06 (d, J = 10.7 Hz).

(Pyridin-3-yl)-methyl-diphosphate (26)

3-(Bromomethyl)pyridine (86 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (3:2 (v/v) 2-propanol/50mM NH4HCO3) yielded 73 mg (45 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.80 (d, JH,P = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.31(dd, J = 7.6 Hz, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.74 (d, J = 22.0 Hz), −5.95 (d, J = 22.0 Hz).

(Pyridin-4-yl)-methyl-diphosphate (27)

4-(Bromomethyl)pyridine (86 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (3:2 (v/v) 2-propanol/50mM NH4HCO3) yielded 65 mg (40 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.92 (d, JH,P = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 8.34 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.66 (d, J = 20.7 Hz), −6.49 (d, J = 20.7 Hz).

(Pyridin-2-yl)-methyl-diphosphate (28)

2-(Bromomethyl)pyridine (86 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (3:2 (v/v) 2-propanol/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 56 mg (35%) of a white solid. 1H NMR(400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.91 (d, JH,P = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.55 (d, J = 22.0 Hz), −6.02 (d, J = 19.4 Hz).

(6-Chloropyridin-3-yl)-methyl-diphosphate (29)

5-(Bromomethyl)-2-chloropyridine (103 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (3:2 (v/v) 2-propanol/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 70 mg (40 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 4.82 (d, JH,P = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (dd, J = 8.4 Hz, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H). 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.73 (d, J = 22.0 Hz), −5.81 (d, J = 22.0 Hz).

Pyridin-3-yl-ethyl-diphosphate (30)

3-(2-Bromoethyl) pyridine (93 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (2:1:1 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 42 mg (25 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 2.87 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 4.00 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.79 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H); 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.78 (1 d, J = 20.6 Hz), −7.07 (d, J = 20.6 Hz).

Pyridin-3-yl-propyl-diphosphate (31)

3-(3-Bromopropyl) pyridine (100 mg, 0.5 mmol) was treated with 1.35 g (1.5 mmol) tris(tetra-n-butylammonium) hydrogen diphosphate in CH3CN (3 mL). Flash chromatography on a cellulose column (4.5:2.5:3.0 (v/v/v) 2-propanol/CH3CN/50 mM NH4HCO3) yielded 57 mg (33 %) of a white solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ 1.75–1.89 (m, 2H), 2.65–2.73 (m, 2H), 3.84 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 7.34–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.74 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (s, 1H), 8.35 (s, 1H). 31P NMR (162 MHz, D2O): δ −9.49 (d, J = 20.7 Hz), −6.87 (d, J = 21.9 Hz).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the United States Public Health Service (NIH grants AI074233, GM073216, GM65307 and GM085774) and the Mississippi Center for Supercomputing Research. We thank Hassan Jomaa and Jochen Wiesner for providing their A. aeolicus IspH plasmid and for initial screening results, Pinghua Liu for the E. coli IspH plasmid, and Thomas B. Rauchfuss for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Rohmer M. Lipids. 2008;43:1095. doi: 10.1007/s11745-008-3261-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiesner J, Jomaa H. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:3. doi: 10.2174/138945007779315551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams SL, McCammon JA. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;73:26. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Ruyck J, Wouters J. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2008;9:117. doi: 10.2174/138920308783955261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jomaa H, Wiesner J, Sanderbrand S, Altincicek B, Weidemeyer C, Hintz M, Turbachova I, Eberl M, Zeidler J, Lichtenthaler HK, Soldati D, Beck E. Science. 1999;285:1573. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borrmann S, Lundgren I, Oyakhirome S, Impouma B, Matsiegui PB, Adegnika AA, Issifou S, Kun JFJ, Hutchinson D, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Kremsner PG. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 2006;50:2713. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rekittke I, Wiesner J, Rohrich R, Demmer U, Warkentin E, Xu W, Troschke K, Hintz M, No JH, Duin EC, Oldfield E, Jomaa H, Ermler U. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17206. doi: 10.1021/ja806668q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grawert T, Rohdich F, Span I, Bacher A, Eisenreich W, Eppinger J, Groll M. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5756. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao Y, Chu L, Sanakis Y, Liu P. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9931. doi: 10.1021/ja903778d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seemann M, Janthawornpong K, Schweizer J, Bottger LH, Janoschka A, Ahrens-Botzong A, Tambou EN, Rotthaus O, Trautwein AX, Rohmer M, Schunemann V. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13184. doi: 10.1021/ja9012408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolff M, Seemann M, Bui BTS, Frapart Y, Tritsch D, Garcia Estrabot A, Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Boronat A, Marquet A, Rohmer M. FEBS Lett. 2003;541:115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulliez E, Ollagnier-de Choudens S, Meier C, Cremonini M, Luchinat C, Trautwein AX, Fontecave M. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:614. doi: 10.1007/s007750050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Hoof S, Lacey CJ, Rohrich RC, Wiesner J, Jomaa H, Van Calenbergh S. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1365. doi: 10.1021/jo701873t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMillan RS, Renaud J, Reynolds JG, Holm RH. J Inorg Biochem. 1979;11:213. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh T, Nagano T, Hirobe M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980;21:1343. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka K, Nakamoto M, Tsunomori M, Tanaka T. Chem Lett. 1987:613. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Y, Smith JM, Flaschenriem CJ, Holland PL. Inorg Chem. 2006;45:5742. doi: 10.1021/ic052136+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelmenschikov V, Case DA, Noodleman L. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:6162. doi: 10.1021/ic7022743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schunn RA, Fritchie CJ, Jr, Prewitt CT. Inorg Chem. 1966;5:892. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crabtree RH. The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. 4. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2005. Chapter 3 and Chapter 5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Telser J, Smith ET, Adams MWW, Conover RC, Johnson MK, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5133. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanders JM, et al. J Med Chem. 2005;48:2957. doi: 10.1021/jm040209d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin MB, Arnold W, Heath HT, 3rd, Urbina JA, Oldfield E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;263:754. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altincicek B, Duin EC, Reichenberg A, Hedderich R, Kollas AK, Hintz M, Wagner S, Wiesner J, Beck E, Jomaa H. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:437. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glide 4.5. Schrodinger, LLC; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang W, Wang K, Liu YL, No JH, Nilges MJ, Oldfield E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grawert T, Span I, Eisenreich W, Rohdich F, Eppinger J, Bacher A, Groll M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913045107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee HI, Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Doan PE, Dos Santos PC, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9563. doi: 10.1021/ja048714n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoll S, Schweiger A. J Magn Reson. 2006;178:42. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maestro 8.0. Schrodinger, LLC; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacroModel 9.5. Schrodinger, LLC; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halgren TA. J Comput Chem. 1996;17:490. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becke AD. Phys Rev A. 1988;38:3098. doi: 10.1103/physreva.38.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perdew JP, Burke K, Wang Y. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1996;54:16533. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.16533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachters A. J Chem Phys. 1970;52:1033. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frisch M. Gaussian 09, Revision A.01. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Gossman W, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16387. doi: 10.1021/ja030340v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Mao J, Godbout N, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13921. doi: 10.1021/ja020298o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Mao J, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7829. doi: 10.1021/ja011583v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Oldfield E. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:4147. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Oldfield E. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:7180. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Oldfield E. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4470. doi: 10.1021/ja030664j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davisson VJ, Woodside AB, Poulter CD. Methods Enzymol. 1985;110:130. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)10068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson W, Perlmutter P, Smallridge A. Aust J Chem. 1988;41:1201. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franceschin M, Alvino A, Casagrande V, Mauriello C, Pascucci E, Savino M, Ortaggi G, Bianco A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:1848. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin MB, Grimley JS, Lewis JC, Heath HT, 3rd, Bailey BN, Kendrick H, Yardley V, Caldera A, Lira R, Urbina JA, Moreno SN, Docampo R, Croft SL, Oldfield E. J Med Chem. 2001;44:909. doi: 10.1021/jm0002578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin MB, Sanders JM, Kendrick H, de Luca-Fradley K, Lewis JC, Grimley JS, Van Brussel EM, Olsen JR, Meints GA, Burzynska A, Kafarski P, Croft SL, Oldfield E. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2904. doi: 10.1021/jm0102809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghosh S, Chan JM, Lea CR, Meints GA, Lewis JC, Tovian ZS, Flessner RM, Loftus TC, Bruchhaus I, Kendrick H, Croft SL, Kemp RG, Kobayashi S, Nozaki T, Oldfield E. J Med Chem. 2004;47:175. doi: 10.1021/jm030084x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanders JM, Ghosh S, Chan JMW, Meints G, Wang H, Raker AM, Song YC, Colantino A, Burzynska A, Kafarski P, Morita CT, Oldfield E. J Med Chem. 2004;47:375. doi: 10.1021/jm0303709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szabo CM, Martin MB, Oldfield E. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2894. doi: 10.1021/jm010279+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davisson VJ, Woodside AB, Neal TR, Stremler KE, Muehlbacher M, Poulter CD. J Org Chem. 1986;51:4768. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.