Abstract

Vimentin is used widely as a marker of the epithelial to mesenchymal transitions (EMTs) that take place during embryogenesis and metastasis, yet the functional implications of the expression of this type III intermediate filament (IF) protein are poorly understood. Using form factor analysis and quantitative Western blotting of normal, metastatic, and vimentin-null cell lines, we show that the level of expression of vimentin IFs (VIFs) correlates with mesenchymal cell shape and motile behavior. The reorganization of VIFs caused by expressing a dominant-negative mutant or by silencing vimentin with shRNA (neither of which alter microtubule or microfilament assembly) causes mesenchymal cells to adopt epithelial shapes. Following the microinjection of vimentin or transfection with vimentin cDNA, epithelial cells rapidly adopt mesenchymal shapes coincident with VIF assembly. These shape transitions are accompanied by a loss of desmosomal contacts, an increase in cell motility, and a significant increase in focal adhesion dynamics. Our results demonstrate that VIFs play a predominant role in the changes in shape, adhesion, and motility that occur during the EMT.—Mendez, M. G., Kojima, S.-I., Goldman, R. D. Vimentin induces changes in cell shape, motility, and adhesion during the epithelial to mesenchymal transition.

The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the process by which epithelial cells dramatically alter their shape and motile behavior as they differentiate into mesenchymal cells. During the EMT, epithelial cells lose their apical-basal polarity and extensive adhesions to neighboring cells and basement membranes. Coincident with the modification of cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesions, the transitioning epithelial cell undergoes a dramatic shape change, adopting an extensively flattened and elongated leading-trailing mesenchymal morphology (for review, see ref. 1). At the same time, cytoskeletal intermediate filaments (IFs) undergo a significant compositional change as epithelial cells, which normally express only keratin IFs (KIFs), initiate the expression of vimentin IFs (VIFs). Because of this dramatic change in IF composition, VIF expression has become a canonical marker of the EMT (e.g., ref. 1). However, little is known about the role of vimentin expression in the EMT. Vimentin is a type III IF protein that self-assembles into homopolymer VIFs and can also form heteropolymers with other type III or IV IFs (2). Keratin consists of type I and II IF proteins, which, in equimolar ratios, assemble into heteropolymeric KIFs (2). When VIF and KIF networks are expressed within the same cell, they form two distinct networks, as they do not copolymerize (3).

During normal embryogenesis, the EMT takes place as individual cells detach from a layer to migrate to a new location. Such developmentally regulated EMTs occur, for instance, during gastrulation and the formation of the primitive streak and somites (for review, see ref. 4). Recently, it has been demonstrated that similar transformations occur during tumorigenesis, metastasis, and fibrosis (e.g. refs. 5,6,7). These observations have broadened the relevance of the EMT and further emphasized that VIF assembly is a hallmark of these changes. For example, VIF expression can be predictive of the recurrence and invasive potential of prostate cancer cells and can be used to determine the origin (basal vs. luminal) of metastatic breast carcinoma cells (8,9,10). VIF expression is also upregulated in model cell culture systems used to study wound healing (11, 12). Furthermore, significant delays in wound healing, attributable to a reduced migratory capability of epithelial cells, are exhibited by vimentin-knockout mice (13).

The reverse process, the mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET), is essential for developmental stages such as the formation of somites and the coelomic cavity, and has been implicated as well in the growth of secondary metastatic tumors (1, 14). During METs, vimentin protein and mRNA expression are downregulated as cell motility decreases and cells adopt epithelial characteristics (14). Vimentin expression is also downregulated following the silencing of the EMT-initiating transcription factors Snail or SIP1 (15, 16).

With respect to the dramatic changes in cell shape that take place during the EMT, evidence indicates that IFs contribute to the determination and maintenance of cell shape. For example, the microinjection of a peptide mimicking the 1A helix initiation sequence of the vimentin central rod domain drives the disassembly of the VIF network and simultaneously has a dramatic effect on the shape of fibroblasts (17). Furthermore, the increased expression or silencing of peripherin, a type III IF, has been shown to enhance or inhibit, respectively, the extension of neuritic processes in PC12 cells (18). In addition, the silencing of the type III IF protein GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) inhibits the formation of astrocytic processes (19).

This study aimed to gain insights into the functional significance of the expression of VIFs in epithelial cells, which normally express only KIFs. Our results demonstrate that the assembly of VIFs is sufficient to induce the changes in cell shape and motility typical of the EMT. Furthermore, these changes are coincident with alterations in cell-cell and cell-substrate adhesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Cultured cells were maintained as follows: MCF-7 cells, MEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM nonessential amino acids (NEAAs), and 0.01 mg/ml bovine insulin. MCF-10A cells, DMEM-F12 with 5% FCS, 10 μg/ml insulin, and 20 ng/ml EGF; MDA-MB-435, DMEM with 10% FCS; MDA-MB-231, Leibovitz L-15 with 10% FCS; human foreskin fibroblasts (hFFs), MEM with 10% FCS and MEM vitamin solution; and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (mEFs) and vim−/−mEFs, DMEM plus 10% FCS and 5 mM NEAAs. To maintain consistently sized MCF-7 colonies, cells were trypsinized until they reached a single-cell suspension, subcultured at a consistent density and allowed to grow for 3 d before transfection.

Fixation and antibodies

Cells were fixed and prepared for immunofluorescence as described previously (18). Antibodies used in these studies were directed against α-tubulin (Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA; MCA77G), β-catenin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; E-5), anti-desmoplakin 1 and 2 (20), desmocoilin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA; clone ZK-31), E-cadherin (Santa Cruz; 67A4), pan-keratin (Sigma; clone C-11), N-cadherin (Santa Cruz; clone K-20), paxillin (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA; 1500-1) and vimentin (clone V9; Sigma or Epitomics; 4211). Fluorophore-tagged phalloidin and all secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA).

Constructs and protein preparation

Construction of the small hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression vectors containing an EGFP reporter is described elsewhere (21, 22). We achieved the greatest degree of vimentin knockdown using 5′-GTACGTCAGCAATATGAAA-3′ (hVIM-T6). The loop sequence between the sense and antisense sequences is 5′-GCTTCCTGTCAC-3′. The negative control shRNA expression vector includes the scrambled sequence (hVIM-sc), 5′-ATGTACTGCGCGTGGAGA-3′. The preparation of GFP-vimentin and myc-vimentin cDNA are described elsewhere (23), as are the preparation of recombinant human vimentin protein (24), Vimrod (25), GFP-paxillin (26), and Vim1A (27).

Transfection and microinjection

All transfections were performed using FuGene6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Prior to microinjection, vimentin and Vimrod were suspended 1.2 mg/ml in injection buffer (5 mM phosphate, pH 7.4) supplemented with tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated 70,000 MW dextran (Molecular Probes; D-1819) to identify injected cells. Injections were performed using an Eppendorf InjectMan NI2 (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY, USA) mounted on a Nikon TE-2000 stand (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Cell shape analysis and fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

Cell shape measurements are expressed as the form factor (FF), 4π(area)/(perimeter)2, which gives a value of 1 for a perfectly circular perimeter and decreasingly smaller positive values for less circular perimeters (28). Fixed cells were imaged as described previously (23). Cell heights were measured by determining the number of confocal sections required to focus from their adhesive to their nonadhesive surfaces after staining with Hoechst and Vybrant CFDA SE Cell Tracer Dye (V12883, Molecular Probes). For some experiments, the minimum concentration of nocodazole necessary for the depolymerization of microtubules (MTs) within 1 h was determined by immunofluorescence: MCF-7 cells, 5 μM; MDA-MB-435 cells, 20 μM; MCA-MB-231 cells, 7.5 μM; and hFFs, 5 μM. For FRAP experiments, cells were triply transfected to express GFP-paxillin, RFP-vimentin, and wild-type vimentin. Wild-type vimentin is included, as we have found it is necessary for the assembly of VIFs (23).

Motility and migration

We used MetaMorph (Molecular Probes) to measure cell velocity after capturing live-image time series at ×10 or ×20. Images were collected by a CoolSnap EZ camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) mounted on a Nikon TE-2000 widefield microscope stand equipped with Perfect Focus. The environment was maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 and humidified by a Tokai Hit Chamber (Tokai Hit, Shizuoka-Ken, Japan). For motility studies, cells were imaged approximately every 5 m for ≥4 h, and their trajectories were traced using the center of the nucleus as a reference point.

Statistics

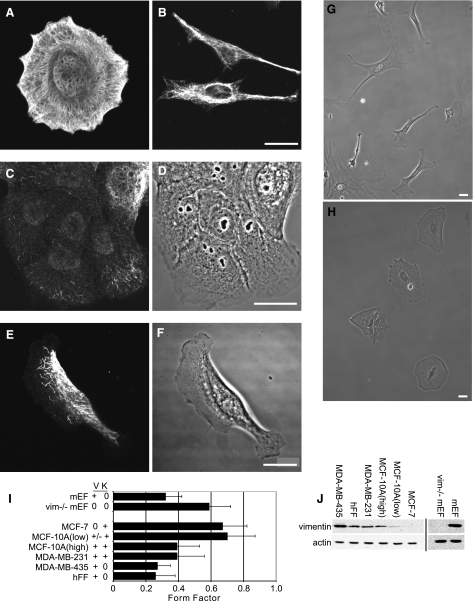

Results are presented as means ± se of ≥3 experiments; results presented in Fig. 1, however, are expressed as means ± sd. P values are determined by 2-tailed Students’ t test of equal variance.

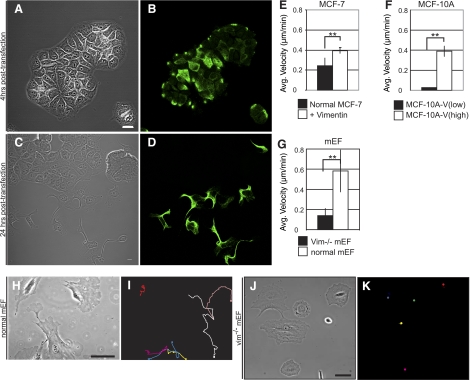

Figure 1.

VIF expression levels correlate with cell shape. A, B) MCF-7 epithelial cells express only KIFs (A), and MDA-MB-435 mesenchymal cells express only VIFs (B). C–F) MCF-10A-V (low) cells contain mainly vimentin particles and squiggles (C, D), while MCF-10A-V (high) cells contain more extensive VIF networks (E, F). G) Normal mEFs. H) Vim−/−mEFs. I) FF of each cell line. J) Immunoblots of whole-cell extracts of the different cell lines. Scale bars = 10 μm.

RESULTS

Cell shape varies with endogenous vimentin IF expression

To gain insights into the role of vimentin in the changes that take place during the EMT, it was important to first establish the relationship between endogenous vimentin expression and cell shape. This assessment was initiated with human MCF-7 cells, a widely used epithelial cell model containing KIFs but not VIFs. Individual MCF-7 cells approximate circular shapes, as determined by FF analysis (Fig. 1A). The average FF of these cells is 0.67 ± 0.15 (n=450) (Fig. 1I), regardless of whether they are single cells (Fig. 1A) or in colonies (e.g., Fig. 6). In contrast, the FFs of mesenchymal cells that express VIFs and are null for KIFs are significantly lower because of their elongated shapes (e.g., Fig. 1B). For example, the FF of hFFs is 0.26 ± 0.12 (n=100); of MDA-MB-435 cells, 0.27 ± 0.08 (n=50) (Fig. 1B, I). We also determined the FF for cell lines that express both KIFs and VIFs. MCF-10A cells, another widely used epithelial cell model, contain extensive KIF networks and varying amounts of VIFs. We isolated and characterized two lines of MCF-10A cells, designated MCF-10A-V (low) and MCF-10A-V (high). The majority of MCF-10A-V (low) cells contain only nonfilamentous vimentin precursor particles and a few loosely arrayed short filaments (Fig. 1C, D). These cells, which grow in colonies, have an FF of 0.70 ± 0.17 (n=50). In contrast, MCF-10A-V (high) cells are more mesenchymal in shape, contain more extensive VIF networks and have an FF of 0.39 ± 0.14 (n=50), a difference of ∼50% relative to MCF-10A-V (low) (Fig. 1E, F, I). Intriguingly, MCF-10A-V (high) cells form few cell-cell contacts when plated at densities similar to those at which the MCF-10A-V (low) cells form colonies. MDA-MB-231 cells, frequently used as a model for studying metastasis, also contain KIFs and VIFs, are mesenchymally shaped, and have an FF of 0.39 ± 0.17 (n=50) (Fig. 1I). We obtained further evidence of the correlation between VIF expression and cell shape by quantitative immunoblotting (Fig. 1J), which shows that MCF-10A (low) cells contain ∼10% of the vimentin expressed in hFFs, while MCF-10A (high), MDA-MB-231, and MDA-MB-435 cells contain ∼50, 170, and 570% of the vimentin present in hFFs, respectively.

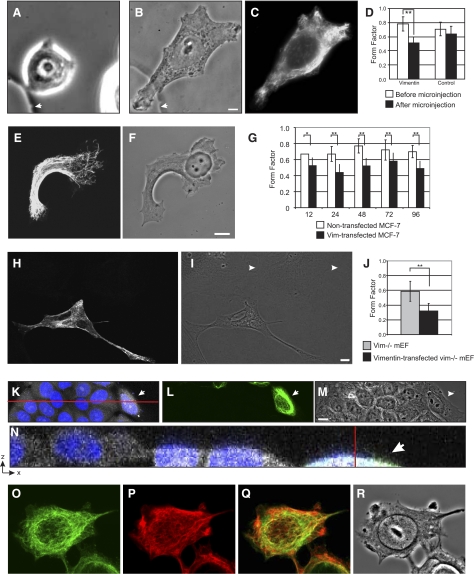

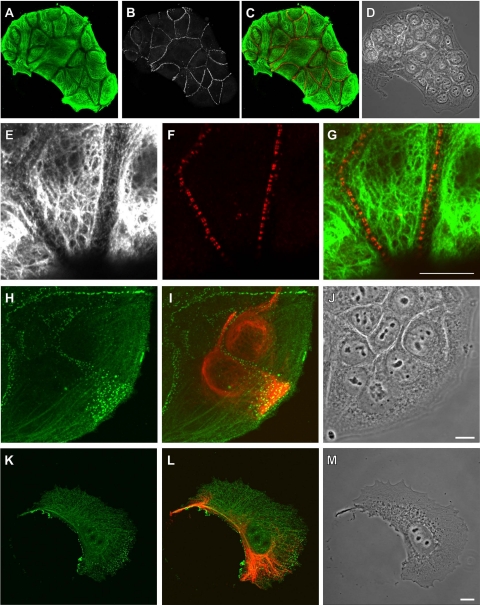

Figure 2.

Vimentin induces epithelial cells to adopt mesenchymal shapes. A–D) An MCF-7 cell immediately before microinjection (A) and 5 h postinjection after processing for immunofluorescence (B, C; vimentin). Arrow indicates fiducial mark on gridded coverslip. At 2–5 h after injection, FFs reflect more mesenchymal shapes(D). E–G) Following transient transfection, MCF-7 cells that contain VIF networks (E) adopt mesenchymal shapes (F). FF of these cells is significantly less than that of control cells (compare to Fig. 1A) on the same coverslip (G). H–J) Vim−/−mEFs expressing VIFs (H) appear like normal mEFs (I, J); arrowheads indicate nontransfected vim−/−mEFs. K–N) MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs are shorter than nontransfected controls. Arrowheads indicate the same cell expressing vimentin. Blue, Hoechst (K, N); green, VIFs (L, N); white, Vybrant dye (M, N). O, P) Expression of KIFs (O) is retained by MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs (P). Q) Overlay of O, P. R) Phase contrast. Bars = 10 μm.

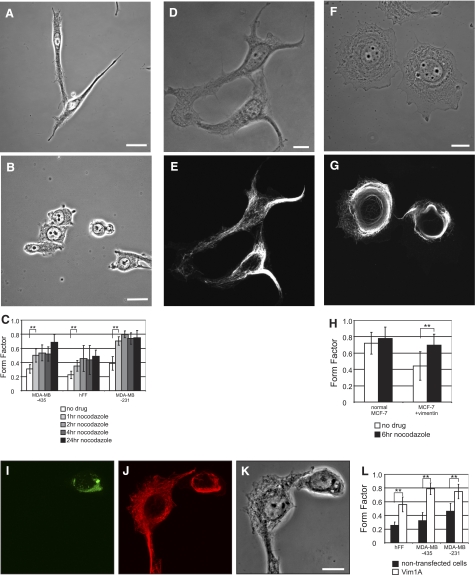

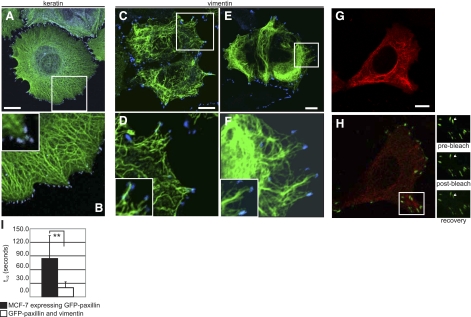

Figure 3.

Reorganization of VIFs induces mesenchymal cells to adopt epithelial-like cell shapes. A–C) MDA-MB-435 cells (A) were exposed to nocodazole for 1–24 h (B; 24 h). FF analysis (C) shows that nocodazole-treated cells become more circular in shape. D–H). VIFs in transfected MCF-7 cells (D, phase contrast; E, immunofluorescence with vimentin antibody of the same cells) reorganize into a perinuclear cap following exposure to nocodazole (F, phase contrast; G, immunofluorescence of the same cell with vimentin antibody). Concurrent with this VIF reorganization, MCF-7 cells containing VIFs revert to more circular shapes (F–H). In contrast, the shapes of normal MCF-7 do not respond to nocodazole treatment (H). I–K) Following transfection with the Vim1A-GFP dominant-negative mutant, VIFs in MDA-MB-435 cells reorganize into perinuclear aggregates. Same field of fixed cells shows Vim1A-GFP(I), immunofluorescence with vimentin antibody (J), and phase contrast (K). L) FF analysis of Vim1A-GFP expressing cells. Scale bars = 10 μm.

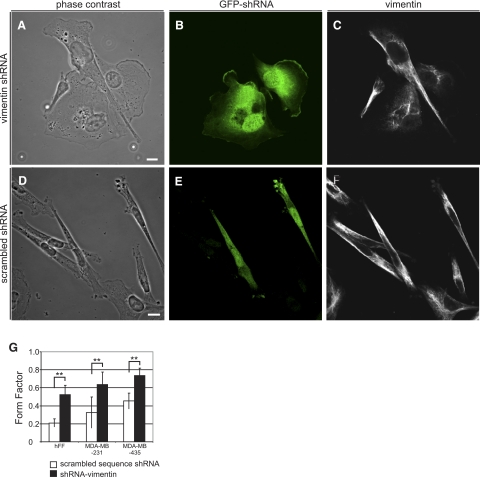

Figure 4.

Vimentin silencing induces mesenchymal cells to adopt epithelial-like cell shapes. A–C) MDA-MB-435 cells silenced with GFP-tagged vimentin shRNA adopt more circular shapes: A) phase contrast; B) immunofluorescence with GFP antibody; C), vimentin. Vimentin that remains in these cells assembles into disorganized short filaments (C). D–F) Cells transfected with GFP-tagged scrambled-sequence control shRNA do not change shape: D) phase contrast; E) immunofluorescence with GFP antibody; F), vimentin. G) Mesenchymal cells respond similarly to vimentin silencing regardless of whether KIFs are also present. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Figure 5.

Motility is enhanced in VIF-expressing epithelial cells. A, B) Four hours following transfection with vimentin cDNA, vimentin-expressing cells are distributed throughout MCF-7 colonies: A) phase contrast; B) vimentin. In the first 2–4 h after transfection (A), vimentin is expressed in most cells. At this time, some cells show extensive expression throughout the cytoplasm; others contain small regions, sometimes concentrated in peripheral regions (B). By ∼6 h post-transfection, obvious vimentin expression is detected in ∼12% of the cells. Although we cannot explain the transient appearance of vimentin in so many cells, it appears that these changes are inherent to the process of transfection. C, D) By 24 h post-transfection, most cells containing VIFs are located at the peripheries of colonies or have moved away from colonies: C) phase contrast; D) vimentin; fixed and processed for immunofluorescence. E–G) Live-cell imaging reveals that MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs move faster than nontransfected cells (E); and that MCF-10A-V (high) cells move faster than MCF-10A-V (low) cells (F). In addition, wild-type mEFs move much faster than vim−/− mEFs (G). H–K) Relative motility is evidenced by the tracings of the positions of nuclei over 6 h (H, I) and 4 h, respectively. It is evident that Vim−/− mEFs are virtually nonmotile (J, K). See Supplemental Movies 1 (normal mEFs) and 2 (vim−/− mEFs). Scale bars = 10 μm (A, C); 100 μm (H, J).

Figure 6.

Desmosomes are internalized in MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs. A–D) Under normal conditions, MCF-7 cells within a colony are linked by desmosomes, as seen by immunofluorescence: A) keratin; B) desmoplakin; C) overlay (desmoplakin, red); D), phase contrast. E–G) Higher magnification views: E) keratin; F) desmoplakin; G) overlay. H–J) Desmosomes (H, green) appear to be undergoing internalization in MCF-7 cells containing VIFs (I, red), as visualized by immunofluorescence (J, phase contrast). K–M) Desmosomes (K; desmoplakin, green) are no longer aligned along the edges of MCF-7 cells that contain VIFs (L, red; M, phase contrast) and are no longer in contact with other cells. Scale bars = 10 μm.

We also compared vim−/− fibroblasts from vimentin-knockout mice, which are devoid of cytoskeletal IFs, with wild-type mEFs (29). As expected, normal mEFs are mesenchymally shaped (Fig. 1G, I), as supported by an FF of 0.27 ± 0.08 (n=100). In contrast, vim−/−mEFs are more circular in shape (Fig. 1H, I) with an FF of 0.59 ± 0.13, P < 0.002 (n=100). These morphometric and immunoblotting analyses show that cell shape correlates with the quantity and organization of endogenously expressed VIFs.

Assembly of exogenous vimentin induces mesenchymal shapes in epithelial cells

Microinjection experiments

To determine the immediate effects of vimentin on epithelial cell shape, we microinjected purified recombinant vimentin into MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2A–D). Within 1–2 h, vimentin formed filaments throughout the cytoplasm, and the MCF-7 cells elongated and adopted shapes with an FF of 0.51 ± 0.9 (n=24), as compared to noninjected cells on the same coverslip with an FF of 0.78 ± 0.1, P < 0.002 (n=50). As a further control, we microinjected MCF-7 cells with a truncated form of vimentin consisting only of the α-helical central rod domain (Vimrod) (25). Vimrod forms coiled-coils in vitro and forms nonfilamentous particles following microinjection. Vimrod-injected MCF-7 cells do not alter their shapes, as shown by an FF of 0.71 ± 0.1 (n=24) (25). The wild-type VIFs assembled in MCF-7 cells persisted for up to 5 h following microinjection and then disappeared over a period of several hours, most likely due to degradation. When the exogenous vimentin was no longer detectable, the microinjected cells reverted to an epithelial shape with an FF indistinguishable from noninjected cells (not shown). These findings demonstrate that VIF assembly in an epithelial cell is sufficient to alter its shape into that of a mesenchymal cell.

Transfection experiments

To generate larger numbers of epithelial cells expressing VIFs for longer time periods, we transfected MCF7 cells with vimentin cDNA. Following the initiation of expression, MCF-7 cells undergo significant morphological changes. Within 12 h, the cells adopt elongated shapes with an FF of 0.44 ± 0.17, compared to mock-transfected controls with an FF of 0.67 ± 0.15, P < 0.002 (Fig. 2E–G; cf. Fig. 1A; n=250). These shape changes persist for ≥96 h, or as long as VIFs are expressed (Fig. 2G). We also examined the ability of VIF expression to rescue the shapes of vim−/−mEFs (Fig. 2H, I). Within 24 h of the initiation of VIF expression, vim−/−mEFs adopt elongated shapes with an FF of 0.32 ± 0.10 (n=33), compared to nontransfected controls with an FF of 0.59 ± 0.13, P < 0.002 (n=116), a difference of ∼100% (Fig. 2J).

Another parameter that has been described for cells undergoing EMT is the flattening of epithelial cells as they adopt the mesenchymal cell morphology. Therefore, we determined whether MCF-7 cells flatten when VIFs are expressed (Fig. 2K–N). To this end, the height of VIF-expressing MCF-7 cells was determined by reconstructing stacks of confocal sections and converting these to sagittal sections (Fig. 2N). Cells expressing VIFs have an average height of 5.3 μm ± 1.0 (n=50), compared to nontransfected cells which average 10.2 μm ± 1.2, P < 0.002 (n=100), a difference of ∼100%. It is important to note that MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs (Fig. 2O) continue to exhibit KIF networks (Fig. 2P) that maintain a distinct organization.

Reorganization of VIF networks alters cell shape

Nocodazole-induced VIF reorganization causes mesenchymal cells to change shape

In numerous types of mesenchymal cells, the distribution and organization of VIFs depend on MTs and their associated motors. Originally this was detected by the retraction of the extensive arrays of VIF networks into juxtanuclear caps in response to MT inhibitors such as colchicine or nocodazole, which also causes cell shape to change (30). However, these shape transitions have not been well documented or quantified. In light of this, we determined the minimal concentration of nocodazole required to depolymerize MTs within 60 min for each of the cell types described above (see Materials and Methods). We then examined the effect of MT depolymerization on the shape of cells expressing only VIFs, VIFs and KIFs, or only KIFs (see below) as a function of time in nocodazole. In hFFs and MDA-MB-435 (VIF only) and MDA-MB-231 (VIF and KIF) cells, FF increased in the presence of nocodazole (Fig. 3A–C). The FF of hFFs and MDA-MB-435 cells increased to 0.35 ± 0.08 (n=102) and 0.50 ± 0.10, P < 0.002 (n=88) in the first hour of nocodazole treatment. Interestingly, MDA-MB-231 cells, widely used as a model of an invasive mesenchymal cell line that contains both VIF and KIF networks, responded most dramatically (Fig. 3C), increasing their FF to 0.70 ± 0.06, P < 0.002 (n=100) within 1 h following the addition of nocodazole.

Nocodazole-induced VIF reorganization also changes the shapes of VIF-expressing epithelial cells

When MCF-7 cells, which contain only KIFs, are treated with nocodazole they do not significantly change shape (Fig. 3H, left). The FF of these cells either in the absence or presence of nocodazole (1 h) is 0.71 ± 0.15 and 0.78 ± 0.14, respectively, P = 0.01 (n=60). However, MCF-7 cells induced to express VIFs have mesenchymal shapes with an average FF of 0.44 ± 0.17 (Fig. 3D, E; also see Fig. 2E–G). When MTs are depolymerized in these cells, their FF increases to 0.67 ± 0.15 after 1 h, P < 0.002 (n=600) (Fig. 3F–H). This result highlights the dominant role of VIFs in the determination of cell shape. These results also demonstrate that the reorganization of VIFs and the concurrent change in FF occur regardless of whether KIFs are also present.

Dominant-negative mutant-induced VIF reorganization causes mesenchymal cells to change shape

Another approach to disrupting VIF network organization involves the expression of a dominant-negative mutant cDNA encoding the first 138 residues of the protein chain, Vim1A (27). When GFP-Vim1A is expressed in cells containing VIFs, it induces the reorganization of the normally extensively distributed VIF network into perinuclear aggregates (Fig. 2I) (27). Unlike the induction of changes in VIFs induced by nocodazole, this technique does not disassemble MTs, nor does it perturb microfilaments (27). In hFFs transfected with GFP-Vim1A for 12–24 h, the FF increases ∼2-fold from 0.26 ± 0.12 (n=102) in controls to 0.56 ± 0.19, P < 0.005 (n=123); the FF of MDA-MB-435 similarly increases from 0.33 ± 0.12 to 0.79 ± 0.09, P < 0.002 (n=15); and that of MDA-MB-231 increases from 0.46 ± 0.11 to 0.75 ± 0.11, P < 0.002 (n=50) as the cells adopt more epithelioid shapes (Fig. 3L).

Silencing vimentin also changes the shapes of mesenchymal cells

To determine whether VIFs are required for the maintenance of mesenchymal cell shape, we examined the effects of silencing vimentin expression by shRNA. The shRNA vector used in these studies also expresses soluble GFP as a marker that identifies silenced cells (Fig. 4B). For control experiments, cells were transfected with a vector expressing a scrambled sequence as well as soluble GFP (Fig. 4D, phase contrast; E, scrambled shRNA; F, vimentin). The disrupted vimentin in the silenced cells typically formed a small cluster of disorganized short filaments near the nucleus (Fig. 4C). Cells in which VIFs were disrupted exhibited dramatic changes in FF of ∼250% (Fig. 4G). The loss of VIFs in hFFs results in a change in FF from 0.21 ± 0.05 (n=50) to 0.52 ± 0.10, P < 0.002 (n=50), an increase of ∼250%. Similarly, the FF of MDA-MB-435 cells increases from 0.45 ± 0.09 (n=50) in controls to 0.74 ± 0.08, P < 0.002 (n=25); and in MDA-MB-231 from 0.32 ± 0.17 (n=25) to 0.64 ± 0.14, P < 0.002 (n=25) (Fig. 4G). As is the case following VIF disassembly by Vim1A, actin and MT networks are retained in these cells (not shown).

Vimentin IF expression increases epithelial cell motility

It is clear that VIF expression induces changes in epithelial cell shape that mimic those seen in the EMT. During the EMT, these changes are accompanied by alterations in motile behavior. Therefore, we determined whether a change occurred in the motile properties of MCF-7 cells following transfection with vimentin cDNA. Under normal culture conditions, MCF-7 cells grow primarily into colonies when observed 72–96 h after plating (∼99% of cells exist in colonies at this time, n=700). Within 4–6 h post-transfection, VIF-expressing cells are distributed throughout these colonies (Fig. 5A, B). By 24 h post-transfection, however, only 9% of transfected cells remain surrounded by cells within their respective colonies; the other 91% (n=350) are located in the peripheral region of the colony and 24% (n=350) of these have moved away and are no longer in contact with other cells (Fig. 5C, D).

Based on these observations, we used live-cell imaging to compare the motile behavior of normal vs. VIF-expressing MCF-7 cells; MCF-10A-V (high) vs. -V (low) cells; and wild-type vs. vim−/−mEFs (Fig. 5E–G). Normal MCF-7 cells move at an average velocity of 0.24 ± 0.08 μm/min (n=20), mainly due to the movement of the entire colony, as is typical of growing epithelial cells (31). MCF-7 cells containing VIFs, however, move ∼66% faster, at speeds of 0.4 μm/min ± 0.03, P < 0.002 (n=5) (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, VIF-expressing MCF-7 cells move individually, rather than as part of a migrating sheet. The velocities of MCF-10A-V (high) and MCF-10A-V (low) also show a relationship between VIF expression and motile behavior (Fig. 5F). MCF-10A-V (high) cells move at 0.39 ± 0.05 μm/min, while the average velocity of MCF-10A-V (low) cells is almost 10-fold less, 0.03 ± 0.00 μm/min, P < 0.002 (n=23). Finally, we compared the motility of vim−/− and wild-type mEFs. Whereas wild-type mEFs (Fig. 5G–I) move at an average velocity of 0.58 ± 0.4 μm/min, vim−/−mEFs exhibit significantly reduced locomotory behavior (0.14 ± 0.2 μm/min, P < 0.002; n=10) (Fig. 5G, J, K and Supplemental Movies 1 and 2).

Vimentin expression affects adhesion

Epithelial cells are highly resistant to shear stress because of the strength of their cell-cell adhesions. Desmosomes, which are tethered to KIFs on their cytoplasmic face by the adaptor protein desmoplakin, contribute to epithelial cell-cell adhesion (32). Because keratin-desmosome interactions are integral to epithelial cell function, and epithelial cells expressing VIFs must lose or break these adhesions in order to move away from their colonies, we examined the localization of the widely used marker for desmosomes, antidesmoplakin (e.g.; 32), in VIF-containing epithelial cells.

Under normal growth conditions, MCF-7 cells contain desmosomes along their cell-cell interfaces (Fig. 6B, F). In the vimentin-expressing MCF-7 cells at the edges of colonies, however, most desmosomes appear to be internalized, as indicated by staining against desmoplakin (Fig. 6H), particularly where two VIF-containing cells are in contact (Fig. 6H–J). In the VIF-expressing MCF-7 cells that have migrated away from the colony, desmosomes appear to have been internalized, and desmoplakin in these cells is no longer aligned along the cell periphery (Fig. 6K–M).

In addition to interactions with desmosomes, KIFs, as reported for other cell types (33), approach and appear to be closely associated with focal adhesions (FAs) in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 7A, B). We observe similar associations of KIFs with FAs when vimentin is expressed in MCF-7 cells. Following transfection, VIFs are also associated with FAs in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 7C–F). This relationship between VIFs and FAs is seen within the first 12 h after transfection, when most of the vimentin is in the form of particles and short filaments, the precursors of long IFs (Fig, 7C, D) (34). As the VIFs lengthen and network formation progresses toward its characteristic organization, VIFs become increasingly associated with FAs, and by 24 h post-transfection >95% of FAs are associated with VIFs (Fig. 7E, F).

Figure 7.

Properties of paxillin are altered in epithelial cells expressing VIFs. A) Immunofluorescence image showing that KIFs in MCF-7 cells extend toward FAs (paxillin, blue). B) Area boxed in A and inset at higher magnification. C–F) Following transfection with vimentin cDNA and processing for immunofluorescence, VIFs are seen to extend toward and become closely associated with FAs (paxillin, blue). This occurs soon after transfection (C, D) and persists as VIF assembly progresses (E, F). Panels D, F and insets show areas boxed in C, E at higher magnification. G) To examine FA dynamics, cells cotransfected with cDNA for wild-type vimentin, RFP-vimentin, and GFP-paxillin were observed live. H) Image of more basal focal plane as the same cell in G. Region indicated by the box in H is seen at higher magnification in the three images to the right, before and after FRAP analysis of a photobleached focal contact. I) The t1/2 to recovery from photobleaching decreases 4-fold in MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs. Scale bars = 10 μm.

Based on observations that VIF expression is coincident with increased motility and that the VIFs expressed in MCF-7 cells associate with FAs, we asked whether VIFs have an effect on FA dynamics. This was accomplished by examining the FRAP of GFP-paxillin (e.g. ref. 35), an adaptor protein that is recruited to all FAs early in their assembly. In MCF-7 cells transfected with GFP-paxillin, FRAP analysis shows a t1/2 for paxillin of 84.6 ± 50.1 s. In contrast, in MCF-7 cells expressing VIFs (Fig. 7G, RFP-vimentin at a higher focal plane of the same cells as Fig. 7H, GFP-paxillin), the t1/2 for paxillin is 20.2 ± 13.1 s, P < 0.005 (n = 16). The rate of paxillin turnover in MCF-7 cells increases by ∼400% when vimentin is expressed (Fig. 7I).

Vimentin does not induce changes in other markers of the EMT

Our results clearly show that VIF expression in epithelial cells alters their shape, adhesions, and motility in a manner consistent with the changes that take place during the EMT. In addition to the expression of VIFs, the EMT is accompanied by well-documented changes in other proteins, including E-cadherin, which is lost from the cell surface, and β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor (for review, see ref. 4). Therefore, we determined whether the introduction of VIFs into MCF-7 cells alters the localization of E-cadherin or β-catenin. Following the induction of VIF expression in MCF-7 cells, E-cadherin retains its position in regions of cell-cell contact, and β-catenin cannot be detected in nuclei (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that the expression of VIFs in epithelial cells is sufficient to induce several important features of the EMT, including the adoption of a mesenchymal shape and increased motility. Furthermore, when VIF organization is altered or silenced in mesenchymal cells, those cells adopt an epithelial-like shape and exhibit reduced motility, changes reminiscent of the MET.

The induction of the changes in epithelial cells coincident with vimentin expression may reflect changes in the crosstalk among the different cytoskeletal systems, which may in turn contribute to the EMT. For example, KIFs rely primarily on microfilaments to maintain their normal organization within the cytoplasm, as evidenced by their retraction into perinuclear aggregates in the presence of latrunculin (36) and findings that keratin subunit motility is primarily actin-dependent (32). On the other hand, VIFs and their precursors interact extensively with MTs, and the motile properties and distribution of all structural forms of vimentin in mesenchymal cells are dependent on MTs and their associated motors, dynein and kinesin (33, 37,38,39). As a result, VIFs are retracted into a juxtanuclear aggregate or cap when MTs are depolymerized with nocodazole (29). In contrast, the distribution of KIFs is not altered significantly when MTs are depolymerized (40). It is therefore likely that the introduction of vimentin into an epithelial cell engages the MT system via mechanisms that do not significantly involve KIFs. It is also possible that vimentin interacts with the actin-containing microfilament system in a fashion distinctly different from that of the KIF system. For example, vimentin binds to the actin-bundling protein fimbrin in adherent cells, and interestingly, binds to residues within one of fimbrin’s two actin binding domains, which suggests that vimentin binding could modulate fimbrin-actin interactions (41). Although reports indicate that keratin interacts with actin (32), no evidence indicates that fimbrin binds to keratin.

Our findings that VIFs induce changes in desmosomal localization and the rate of paxillin turnover are particularly interesting, as they suggest that VIF-mediated interactions are dominant over those involving KIFs. This possibility is supported by the recent findings that both KIFs in epithelial cells (32) and VIFs in endothelial cells (42) are closely associated with FAs, although the functional significance of these associations remains largely unknown. Our results also provide additional evidence of a role for IFs in the modulation of FAs. Previous evidence of the modulatory capabilities of VIFs come from reductions in both the size and strength of adhesion of β3-integrin-containing focal contacts in vimentin-silenced endothelial cells subjected to flow (43), as well as findings that the normal localization of β1-integrin-containing focal contacts requires the phosphorylation of vimentin by protein kinase C (PKC) (44). In addition, an altered distribution of FAs has been reported in fibroblasts obtained from the vimentin knockout mouse (13).

It is also possible that the expression of VIFs in epithelial cells influences the transition to a mesenchymal phenotype by participating in signal transduction. For example, it has been shown that the phosphorylated MAP kinases pErk1 and pErk2 are stabilized by binding to vimentin during their transport from the site of neuronal injury to the nucleus (45). Furthermore, direct binding to VIFs sequesters 14–3-3ζ, thereby blocking its ability to activate factors including oncogenic Raf, an effector of the MEK/Erk pathway (46). Binding to vimentin also protects Scrib, a component of the Scribble complex involved in the determination of cellular polarity, from proteosomal degradation (47). VIFs are also known to be substrates for a variety of second messengers, especially protein kinases, which alter VIF assembly states and organization in vivo (48). Many of these kinases participate in the regulation of cell adhesion and/or motility while also phosphorylating vimentin. p21-activated kinase (PAK), for example, modulates motility and the formation of lamellipodia by mediating actin polymerization (49); and ROKα mediates microfilament reorganization and myosin contractility (50, 51). In further support of a role for VIFs in the regulation of cell motility are the findings that PKC-dependent phosphorylation of vimentin is required for mouse fibroblast motility (44) and that phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ (PI3Kγ)-dependent phosphorylation of vimentin modulates leukocyte transmigration (52). Together, these results suggest that VIFs play a key role in the signal transduction pathways that contribute to mesenchymal cell behavior.

Finally, VIF expression may also play an important role in modulating an epithelial cell’s response to mechanical stress during the EMT. For example, our results show that epithelial cells expressing VIFs are flatter than normal epithelial cells expressing only KIFs. The height of cells above their growth substrates has been shown to be a determining factor in the response of epithelial and endothelial cells to shear stress; flatter cells are much less sensitive to shear stress relative to taller, neighboring cells (53, 54). The epithelial cell flattening induced by vimentin expression may therefore facilitate the ability of these cells to withstand a variety of external mechanical forces. This may be a critical factor for the survival of metastatic cells, which are exposed to abnormal physical stresses as they navigate from primary to secondary tumor sites (reviewed in ref. 55). Furthermore, the assembly of VIFs in epithelial cells during the EMT may alter their deformability. In support of this, evidence shows that VIFs and KIFs respond differently to mechanical stress. For example, VIFs in endothelial cells are displaced in the direction of external fluid shear throughout the cytoplasm within minutes, evidence suggesting that they are relatively flexible structures (56). In contrast, KIFs in lung epithelial cells respond to shear stress by bundling, decreasing their network mesh size and increasing their stiffness (52, 57). Considering that the change in IF expression is the most significant cytoskeletal alteration that accompanies the EMT, it may be that the normal transition from KIFs to VIFs during the EMT underlies the reduced stiffness exhibited by metastatic cells relative to normal epithelial cells (e.g., ref. 58). Further support for this possibility is derived from in vitro analyses demonstrating that IFs exhibit strain hardening properties, and that these properties differ according to IF type (59, 60). Measurements of the elasticity of individual IFs by atomic force microscopy show that keratin is stiffer than desmin, a type III IF with significant sequence homology to vimentin (61). Furthermore, photobleaching experiments show that vimentin IFs are more dynamic and undergo subunit exchange ∼10× faster than KIFs within the same cell, results which also suggest that the VIF network may be more flexible or responsive than KIFs (39). These data also show that the expression of VIFs in the EMT, long considered an epiphenomenon, is critically important in determining the behavioral properties of vertebrate cells. Future studies of the molecular mechanisms underlying the specific role of vimentin, especially with respect to the other cytoskeletal systems, are essential for a comprehensive understanding of cell shape determinism and motility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by a grant from the General Medical Sciences Institute of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R37 GM36806–27). The authors also thank Brian Helfand, Ed Kuczmarski, Boris Grin, and Anne Goldman for helpful comments.

References

- Hay E D. The mesenchymal cell, its role in the embryo, and the remarkable signaling mechanisms that create it. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:706–720. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert P M, Idler W W, Cabral F, Gottesman M M, Goldman R D. In vitro assembly of homopolymer and copolymer filaments from intermediate filament subunits of muscle and fibroblastic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:3692–3696. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.6.3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke W W, Schiller D L, Hatzfeld M, Winter S. Protein complexes of intermediate-sized filaments: melting of cytokeratin complexes in urea reveals different polypeptide separation characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:7113–7117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acloque H, Adams M S, Fishwick K, Bronner-Fraser M, Nieto M A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: the importance of changing cell state in development and disease. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1438–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI38019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K K, Kugler M C, Wolters P J, Robillard L, Galvez M G, Brumwell A N, Sheppard D, Chapman H A. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13180–13185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605669103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini D, Ceccarelli C, Taffurelli M, Pileri S, Marrano D. Differentiation pathways in primary invasive breast carcinoma as suggested by intermediate filament and biopathological marker expression. J Pathol. 1996;179:386–391. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199608)179:4<386::AID-PATH631>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, Xu G, Wu M, Zhang Y, Li Q, Liu P, Zhu T, Song A, Zhao L, Han Z, Chen G, Wang S, Meng L, Zhou J, Lu Y, Wang S, Ma D. Overexpression of vimentin contributes to prostate cancer invasion and metastasis via src regulation. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang S H, Hyde C, Reid I N, Hitchcock I S, Hart C A, Bryden A A, Villette J M, Stower M J, Maitland N J. Enhanced expression of vimentin in motile prostate cell lines and in poorly differentiated and metastatic prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 2002;52:253–263. doi: 10.1002/pros.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Helfand B T, Jang T L, Zhu L J, Chen L, Yang X J, Kozlowski J, Smith N, Kundu S D, Yang G, Raji A A, Javonovic B, Pins M, Lindholm P, Guo Y, Catalona W J, Lee C. Nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of vimentin is an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3557–3567. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo H, Ackland M L, Blick T, Lawrence M G, Clements J A, Williams E D, Thompson E W. Epithelial–mesenchymal and mesenchymal–epithelial transitions in carcinoma progression. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:374–383. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles C, Polette M, Zahm J M, Tournier J M, Volders L, Foidart J M, Birembaut P. Vimentin contributes to human mammary epithelial cell migration. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4615–4625. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.24.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix M J, Seftor E A, Seftor R E, Trevor K T. Experimental co-expression of vimentin and keratin intermediate filaments in human breast cancer cells results in phenotypic interconversion and increased invasive behavior. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:483–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckes B, Colucci-Guyon E, Smola H, Nodder S, Babinet C, Krieg T, Martin P. Impaired wound healing in embryonic and adult mice lacking vimentin. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2455–2462. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.13.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffer C L, Brennan J P, Slavin J L, Blick T, Thompson E W, Williams E D. Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition facilitates bladder cancer metastasis: role of fibroblast growth factor receptor-2. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11271–11278. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindels S, Mestdagt M, Vandewalle C, Jacobs N, Volders L, Noel A, van Roy F, Berx G, Foidart J M, Gilles C. Regulation of vimentin by SIP1 in human epithelial breast tumor cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:4975–4985. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmeda D, Jorda M, Peinado H, Fabra A, Cano A. Snail silencing effectively suppresses tumour growth and invasiveness. Oncogene. 2007;26:1862–1874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R D, Khuon S, Chou Y H, Opal P, Steinert P M. The function of intermediate filaments in cell shape and cytoskeletal integrity. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:971–983. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand B T, Mendez M G, Pugh J, Delsert C, Goldman R D. A role for intermediate filaments in determining and maintaining the shape of nerve cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:5069–5081. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein D E, Shelanski M L, Liem R K. Suppression by antisense mRNA demonstrates a requirement for the glial fibrillary acidic protein in the formation of stable astrocytic processes in response to neurons. J Cell Biol. 1991;112:1205–1213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.112.6.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K J, Geiger B, Jones J C, Talian J C, Goldman R D. The relationship between intermediate filaments and microfilaments before and during the formation of desmosomes and adherens-type junctions in mouse epidermal keratinocytes. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1389–1402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.5.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp T R, Bernards R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S, Vignjevic D, Borisy G G. Improved silencing vector co-expressing GFP and small hairpin RNA. BioTechniques. 2004;36:74–79. doi: 10.2144/04361ST02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon M, Moir R D, Prahlad V, Goldman R D. Motile properties of vimentin intermediate filament networks in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:147–157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou Y H, Opal P, Quinlan R A, Goldman R D. The relative roles of specific N- and C-terminal phosphorylation sites in the disassembly of intermediate filament in mitotic BHK-21 cells. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:817–826. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann H, Haner M, Brettel M, Muller S A, Goldie K N, Fedtke B, Lustig A, Franke W W, Aebi U. Structure and assembly properties of the intermediate filament protein vimentin: the role of its head, rod and tail domains. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:933–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukaitis C M, Webb D J, Donais K, Horwitz A F. Differential dynamics of alpha 5 integrin, paxillin, and alpha-actinin during formation and disassembly of adhesions in migrating cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:1427–1440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.7.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Barlan K, Chou Y H, Grin B, Lakonishok M, Serpinskaya A S, Shumaker D K, Herrmann H, Gelfand V I, Goldman R D. The dynamic properties of intermediate filaments during organelle transport. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2914–2923. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D R, Voss E, Varnum-Finney B, Wessels D. Dynamic Morphology System: a method for quantitating changes in shape, pseudopod formation, and motion in normal and mutant amoebae of Dictyostelium discoideum. J Cell Biochem. 1988;37:177–192. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240370205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci-Guyon E, Portier M M, Dunia I, Paulin D, Pournin S, Babinet C. Mice lacking vimentin develop and reproduce without an obvious phenotype. Cell. 1994;79:679–694. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R D. The role of three cytoplasmic fibers in BHK-21 cell motility. I. Microtubules and the effects of colchicine. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:752–762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.3.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schock F, Perrimon N. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:463–493. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.022602.131838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godsel L M, Hsieh S N, Amargo E V, Bass A E, Pascoe-McGillicuddy L T, Huen A C, Thorne M E, Gaudry C A, Park J K, Myung K, Goldman R D, Chew T L, Green K J. Desmoplakin assembly dynamics in four dimensions: multiple phases differentially regulated by intermediate filaments and actin. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:1045–1059. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windoffer R, Kolsch A, Woll S, Leube R E. Focal adhesions are hotspots for keratin filament precursor formation. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:341–348. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahlad V, Yoon M, Moir R D, Vale R D, Goldman R D. Rapid movements of vimentin on microtubule tracks: kinesin-dependent assembly of intermediate filament networks. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:159–170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfenson H, Lubelski A, Regev T, Klafter J, Henis Y I, Geiger B. A role for the juxtamembrane cytoplasm in the molecular dynamics of focal adhesions. PloS One. 2009;4:e4304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woll S, Windoffer R, Leube R E. Dissection of keratin dynamics: different contributions of the actin and microtubule systems. Eur J Cell Biol. 2005;84:311–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyoeva F K, Gelfand V I. Coalignment of vimentin intermediate filaments with microtubules depends on kinesin. Nature. 1991;353:445–448. doi: 10.1038/353445a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfand B T, Mikami A, Vallee R B, Goldman R D. A requirement for cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin in intermediate filament network assembly and organization. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:795–806. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G, Gundersen G G. Kinesin is a candidate for cross-bridging microtubules and intermediate filaments. Selective binding of kinesin to detyrosinated tubulin and vimentin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9797–9803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon K H, Yoon M, Moir R D, Khuon S, Flitney F W, Goldman R D. Insights into the dynamic properties of keratin intermediate filaments in living epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:503–516. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia I, Chu D, Chou Y H, Goldman R D, Matsudaira P. Integrating the actin and vimentin cytoskeletons. adhesion-dependent formation of fimbrin-vimentin complexes in macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:831–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya R, Gonzalez A M, Debiase P J, Trejo H E, Goldman R D, Flitney F W, Jones J C. Recruitment of vimentin to the cell surface by β3 integrin and plectin mediates adhesion strength. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1390–1400. doi: 10.1242/jcs.043042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta D, Jones J C. The vimentin cytoskeleton regulates focal contact size and adhesion of endothelial cells subjected to shear stress. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4977–4984. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivaska J, Vuoriluoto K, Huovinen T, Izawa I, Inagaki M, Parker P J. PKCepsilon-mediated phosphorylation of vimentin controls integrin recycling and motility. EMBO J. 2005;24:3834–3845. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlson E, Michaelevski I, Kowalsman N, Ben-Yaakov K, Shaked M, Seger R, Eisenstein M, Fainzilber M. Vimentin binding to phosphorylated Erk sterically hinders enzymatic dephosphorylation of the kinase. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:938–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzivion G, Luo Z J, Avruch J. Calyculin A-induced vimentin phosphorylation sequesters 14-3-3 and displaces other 14-3-3 partners in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29772–29778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phua D C, Humbert P O, Hunziker W. Vimentin regulates scribble activity by protecting it from proteasomal degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2841–2855. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Goldman R D. Intermediate filaments mediate cytoskeletal crosstalk. Nat Rev. 2004;5:601–613. doi: 10.1038/nrm1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molli P R, Li D Q, Murray B W, Rayala S K, Kumar R. PAK signaling in oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28:2545–2555. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto H, Tanabe K, Manser E, Lim L, Yasui Y, Inagaki M. Phosphorylation and reorganization of vimentin by p21-activated kinase (PAK) Genes Cells. 2002;7:91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1356-9597.2001.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin W-C, Chen X-Q, Leung T, Lim L. RhoA-Binding Kinase alpha Translocation is facilitated by the collapse of the vimentin intermediate filament network. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6325–6339. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis L, Pasquali C, Bertschy-Meier D, Cuccurullo A, Costa C, Ambrogio C, Vilbois F, Chiarle R, Wymann M, Altruda F, Rommel C, Hirsch E. Leukocyte transmigration is modulated by chemokine-mediated PI3Kgamma-dependent phosphorylation of vimentin. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1136–1146. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P F, Mundel T, Barbee K A. A mechanism for heterogeneous endothelial responses to flow in vivo and in vitro. J Biomech. 1995;28:1553–1560. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flitney E W, Kuczmarski E R, Adam S A, Goldman R D. Insights into the mechanical properties of epithelial cells: the effects of shear stress on the assembly and remodeling of keratin intermediate filaments. FASEB J. 2009;23:2110–2119. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-124453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh S. Biomechanics and biophysics of cancer cells. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:413–438. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmke B P, Goldman R D, Davies P F. Rapid displacement of vimentin intermediate filaments in living endothelial cells exposed to flow. Circ Res. 2000;86:745–752. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan S, DeGiulio J V, Lorand L, Goldman R D, Ridge K M. Micromechanical properties of keratin intermediate filament networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:889–894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710728105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross S E, Jin Y S, Rao J, Gimzewski J K. Nanomechanical analysis of cells from cancer patients. Nat Nanotech. 2007;2:780–783. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Xu J, Coulombe P A, Wirtz D. Keratin filament suspensions show unique micromechanical properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19145–19151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janmey P A, Shah J V, Janssen K P, Schliwa M. Viscoelasticity of intermediate filament networks. Subcell Biochem. 1998;31:381–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreplak L, Bar H, Leterrier J F, Herrmann H, Aebi U. Exploring the mechanical behavior of single intermediate filaments. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:569–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.