Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a crucial anatomic location in the brain. Its dysfunction complicates many neurodegenerative diseases, from acute conditions, such as sepsis, to chronic diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Several studies suggest an altered BBB in lupus, but the underlying mechanism remains unknown. In the current study, we observed a definite loss of BBB integrity in MRL/MpJ-Tnfrsf6lpr (MRL/lpr) lupus mice by IgG infiltration into brain parenchyma. In line with this result, we examined the role of complement activation, a key event in this setting, in maintenance of BBB integrity. Complement activation generates C5a, a molecule with multiple functions. Because the expression of the C5a receptor (C5aR) is significantly increased in brain endothelial cells treated with lupus serum, the study focused on the role of C5a signaling through its G-protein-coupled receptor C5aR in brain endothelial cells, in a lupus setting. Reactive oxygen species production increased significantly in endothelial cells, in both primary cells and the bEnd3 cell line treated with lupus serum from MRL/lpr mice, compared with those treated with control serum from MRL+/+ mice. In addition, increased permeability monitored by changes in transendothelial electrical resistance, cytoskeletal remodeling caused by actin fiber rearrangement, and increased iNOS mRNA expression were observed in bEnd3 cells. These disruptive effects were alleviated by pretreating cells with a C5a receptor antagonist (C5aRant) or a C5a antibody. Furthermore, the structural integrity of the vasculature in MRL/lpr brain was maintained by C5aR inhibition. These results demonstrate the regulation of BBB integrity by the complement system in a neuroinflammatory setting. For the first time, a novel role of C5a in the maintenance of BBB integrity is identified and the potential of C5a/C5aR blockade highlighted as a promising therapeutic strategy in SLE and other neurodegenerative diseases.—Jacob, A., Hack, B., Chiang, E., Garcia, J. G. N., Quigg, R. J., Alexander, J. J. C5a alters blood-brain barrier integrity in experimental lupus.

Keywords: endothelium, complement system, systemic lupus erythematosus, neurodegeneration

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex, multiorgan disease that is poorly understood (1,2,3). With increasing clinical awareness, even though neuropsychiatric (NP) problems are identified in many SLE patients, the culprit (or culprits) causing the disease remains an enigma, with few therapeutic options (4,5,6,7,8,9,10). SLE is a multifaceted disease with an array of symptoms and in which complement activation is a key event.

The complement (C) cascade, an important arm of the innate immune system, is a double-edged sword; when excessively activated, its beneficial effects can become detrimental to the host (11,12,13,14). Complement activation can be triggered through four different pathways that ultimately converge to form the terminal membrane attack complex (MAC) with the generation of C3a and C5a (15). The anaphylatoxin C5a is a 74-aa fragment of C5 and binds to its G-coupled receptor, C5aR, inducing potent inflammatory effects. C5aR is present on the blood cells such as neutrophils and platelets that infiltrate the brain in different inflammatory settings and is also constitutively expressed on several cell types in the brain (16, 17). It mediates several biological processes, including chemotaxis and degranulation of mast cells and basophils, vascular permeability, increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and cytokine production (18, 19). It could cause the intravascular aggregation of neutrophils with subsequent leukostatic occlusion of the cerebral arteries, contributing to vascular injury. C5a can be neurotoxic (20) or neuroprotective (21), depending on the setting (22). Its receptor C5aR appears to be down-regulated in the hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease patients but up-regulated in the caudate of Huntington’s disease patients and in animal models of neurological trauma (16, 20).

In SLE patients, significantly elevated levels of the complement activation products have correlated with a poor outcome (23, 24). In experimental SLE, Alexander and colleagues (25,26,27,28) previously demonstrated that the complement inhibition attenuates disease symptoms in brain. However, the role of complement in the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a crucial anatomic location in the brain, remains an enigma. The BBB represents a dynamic interface between the circulatory system and the brain (29,30,31). The vascular endothelium regulates cellular metabolite levels, vascular tone, and hemostasis as well as the ingress and egress of leukocytes to and from the brain (32, 33). The brain endothelium is damaged and may be an important contributing factor in the pathogenesis in NPSLE (29, 34). Vascular damage could lead to secondary neuronal disorder, where autoantibodies gain access to the brain and cause neuronal dysfunction (35,36,37).

A crucial mechanism for BBB breakdown in an SLE setting could be immune-mediated attack and complement activation. The goal of this study was to understand the role of C5a/C5aR signaling in BBB integrity in SLE. The results of previous studies had shown that inhibition of complement activation at the level of C3 convertase by Crry (38) significantly alleviated CNS disease in MRL/MpJ-Tnfrsf6lpr (MRL/lpr) mice (26). Given that C3 convertase inhibition prevents the generation of C5a (as well as of C3a, C3b, and C5b-9) (12, 39, 40), it is conceivable that the therapeutic effects observed with Crry treatment were secondary to its effect to limit generation of C5a. Furthermore, manipulation of C5a/C5aR signaling would leave the complement cascade intact to perform the normal protective functions; therefore, it is a more viable therapeutic candidate than Crry, the pan complement inhibitor.

We studied the role of C5a in experimental SLE brain using a small-molecule inhibitor, C5a receptor antagonist (C5aRant), and MRL/lpr (41) mice, the most widely used tool to study SLE (42). These mice are known to accurately reflect human SLE, including the NP manifestations (8, 43,44,45). They respond to cyclophosphamide and prednisolone, the existing therapy for lupus patients (46,47,48,49). MRL/lpr mice differ from the congenic MRL/MpJ (MRL+/+) strain by the nearly complete absence of the proapoptotic membrane Fas protein because of a retroviral insertion in the Tnfrsf6 gene (41, 50,51,52).

In addition, the role of C5a in brain endothelial cells was studied using both the cell line bEnd3 and a primary culture of brain endothelial cells. The results of this study demonstrate that C5a/C5aR signaling regulates iNOS and ROS generation, leading to actin cytoskeletal reorganization and altered BBB permeability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental protocol in lupus mice

MRL/lpr and MRL+/+ mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), and the BBB integrity was determined as follows. At 20 wk of age, the mice were injected intravenously with 0.2 ml of Alexa 488-labeled IgG (1 mg/ml) and sacrificed 15 min later, and the brains were harvested. These studies were approved by the University of Chicago Animal Care and Use Committee. Cerebral cortexes were snap-frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. (optimal cutting temperature) compound (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA), placed in precooled 2-methylbutane, and stored at −80°C until use. Cryosections (7 μm) were observed with a Zeiss microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Cells in culture

bEnd3 cells

The bEnd3 immortalized mouse brain endothelial cell line (American Type Tissue Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA) was used for these studies (53). Cells were seeded at a density of 0.5–1.0 × 104 cells/cm2 onto tissue culture-treated plastic ware and grown in DMEM with 4.5 g/L glucose, 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 4 mM glutamine, 10% FCS, and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells stained positively with platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) and agglutinin, indicating their endothelial characteristics.

Primary culture

Cerebral microvascular endothelial cells were isolated from 2-wk-old C57BL6 mice according to published protocols (54), with modifications. Briefly, mice were euthanized, and their brains were collected in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cerebella, white matter, meninges, and visible blood vessels of the brain were removed. The cortex was cut into small pieces and homogenized using 10 strokes with a dounce homogenizer (0.5 mm clearance). Homogenates were mixed 1:1 with 30% dextran and centrifuged at 3000 g for 25 min. The pellet was digested in 3 ml of DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) containing DNase (10 μg/ml) and collagenase (2 mg/ml) at 37°C in a shaking water bath for 30 min. The pellet was washed in medium; plated onto collagen IV-plated dishes (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA); and grown in DMED/F12 medium supplemented with 20% plasma-derived serum (Animal Technologies, Inc., Tyler, TX, USA), 2 mM glutamine, 0.5 U/ml heparin, 1 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF), penicillin and streptomycin (100 U/ml), and gentamicin (50 μg/ml). Twenty-four hours after plating, red blood cells, cell debris, and nonadherent cells were removed by washing with medium. Passage 2 endothelial cells were used in the present study. Cells stained positively with anti-vascular endothelial (VE) cadherin (see Fig. 2A) and anti-CD31 (not shown).

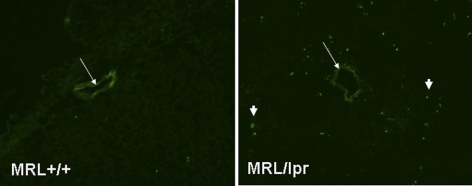

Figure 1.

BBB integrity is altered in MRL/lpr mice. Mice at 20 wk of age were injected with Alexa 488-labeled IgG (0.25 ml i.v. of 2 mg/ml) and sacked 15 min later. Brains were harvested, cryosectioned, and observed using a Zeiss microscope. Representative sections from MRL+/+ mouse brain (left; control) indicate that labeled IgG was taken up by the endothelial cells. In contrast, sections from MRL/lpr mouse brain (right) demonstrate the presence of IgG in the brain parenchyma as well as in endothelial cells, indicating loss of BBB integrity.

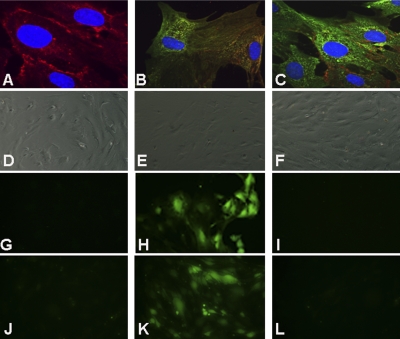

Figure 2.

C5aR regulates ROS generation in primary endothelial cells. Primary endothelial cells were isolated from 2-wk-old C57BL6 pups. They stained positive for VE-cadherin (A). C5aR expression was increased in cells treated with lupus serum (C) compared with cells treated with control serum (B). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. ROS generation was increased in primary endothelial cells (H) and bEnd3 cells (K) treated with lupus serum compared with primary endothelial cells (G) and bEnd3 cells (J) treated with control serum as described in Materials and Methods. Pretreatment of cells with anti-C5a (I) or C5aRant (L) prevented ROS generation in lupus serum-treated cells. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images in panels D–F correspond to panels G–I, respectively. Representative images from 3 experiments are shown.

Treatment of cells

Cells were treated with serum isolated from 20-wk-old mice (control serum from MRL+/+ mice, lupus serum from MRL/lpr mice). The activity of C5a was inhibited in the serum-treated cells with 1 μM C5aRant [acetyl-Phe-(Orn-Pro-D-cyclohexylalanine)-Trp-Arg], obtained from Dr. John Lambris (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA) or anti-mouse C5a (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Imaging of cells

After the cells reached confluency, the medium was replaced with DMEM (Gibco BRL, Chagrin Falls, OH, USA) with 2% FBS for synchronization. Cells were subjected to the different treatments (5% control serum, 5% lupus serum, or 1 μM C5aRant+5% lupus serum) for 3 h. So the cytoskeletal rearrangement could be observed, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, and the actin filaments were visualized using Texas Red-conjugated phalloidin. Cells were mounted with ProLong Gold Antifade (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) and observed using a Zeiss microscope. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop imaging software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Assessment of transendothelial electrical resistance

An alteration in cytoskeletal proteins could change the permeability of the endothelial layer. Because resistance is inversely proportional to permeability, transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) was measured across confluent bEnd3 monolayers using the electrical cell substrate impedance sensing system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY, USA) as previously described (55, 56). Cells were cultured on small gold electrodes (10−4 cm2), and culture medium was used as an electrolyte. Cells were treated with 5% control serum, 5% lupus serum, and 1 μM C5aRant + 5% lupus serum. TEER values were obtained before treatment (baseline) and after treatment, and are expressed as relative changes in TEER values as a percentage of the baseline value (57).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on RNA isolated from bEnd3 cells using a QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit on an ABI 7700 sequence detector (both from Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). Primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA) and probes by Synthegen (Houston, TX, USA). Data were normalized to 18S RNA. The primers and probes used were as follows, where GAPDH is glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase: GAPDH forward 5′-GCAAATTCAACGGCACAGT-3′, reverse 5′-AGATGGTGATGGGCTTCCC-3′, probe 5′-AGGCCGAGAATGGGAAGCTTGTCATC-3′; iNOS forward 5′-CAGCTGGGCTGTACAAACCTT-3′, reverse 5′-TGAATGTGATGTTTGCTTCGG-3′, probe 5′-CGGGCAGCCTGTGAGACCTTTGA-3′.

Estimation of ROS generated in endothelial cells

Cells were treated with 2% FBS-containing medium plus the various treatments (5% control serum, 5% lupus serum, or 1 μM C5aRant or anti-C5a + 5% lupus serum) for 3 h at 37°C. Thirty minutes before the end of treatment, carboxy-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen; final concentration 25 μM) was added to the cells. Wells were washed 3 times with DPBS with calcium and magnesium (Invitrogen) at 37°C, and live cells were imaged at ×200 using an IX81 scope with a DP70 camera (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as means ± se and were analyzed using Minitab 12 statistical software (Minitab, State College, PA, USA). For comparisons between 2 groups at 1 time point, t testing was used for parametric data and Mann-Whitney testing for nonparametric data. Potential correlations among variables were determined by calculating Pearson product moment correlation coefficients and their P values. Significance was determined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Blood-brain barrier integrity is altered in lupus mice

Representative cortical cryosections from brains of MRL/lpr and MRL+/+ mice that were injected intravenously with Alexa488-labeled anti-mouse IgG were observed under the microscope. IgG was taken up by the microvasculature in control mice but moved from the endothelial cells into the parenchyma in sections from MRL/lpr brains (Fig. 1), indicating an alteration of the BBB integrity. Therefore, we decided to study the effect of lupus on brain endothelial cells.

C5a regulates ROS expression in endothelial cells

C5aR expression on primary endothelial cells was increased when treated with lupus serum from MRL/lpr mice (Fig. 2C) compared with control serum from MRL+/+ mice (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, cells treated with lupus serum exhibited significant ROS generation (Fig. 2H) compared with cells treated with control serum (Fig. 2G), in which it was undetectable. A similar regulation of ROS production by lupus serum treatment was observed in the endothelial cell line bEnd3 (Fig. 2J, K). ROS has been shown to induce cytoskeletal alterations in endothelial cells (58), which could affect the BBB integrity. Inhibition of C5a alleviated the ROS increase in both primary endothelial cells and bEnd3 cells (Fig. 2I, L). Because the response in the bEnd3 cells was comparable with that in the primary endothelial cells, all further experiments were done using bEnd3 cells.

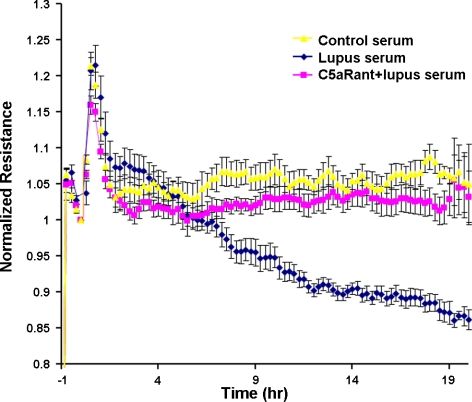

C5a regulates BBB permeability through C5aR signaling

To analyze BBB integrity, TEER was measured across bEnd3 monolayers after challenge with the conditions described in Materials and Methods. As demonstrated in Fig. 3, TEER values dramatically decreased in lupus serum-treated cells compared with cells treated with control serum. Pretreatment of cells with C5aRant alleviated the decrease in TEER, which approached normal values. These results indicate the key role of C5a in endothelial layer integrity, signaling through its receptor C5aR.

Figure 3.

C5a regulates TEER of endothelial cells signaling through C5aR. bEnd3 cells were grown as described in Materials and Methods, and after 3 h of treatment, TEER was monitored over time. Changes in TEER (%) are expressed as means ± se. Pooled data from 3 independent experiments are shown. Effects of different treatments (5% control serum, 5% lupus serum, or 1 μM C5aRant+5% lupus serum) were recorded. Increased permeability was observed after treatment with lupus serum compared with control serum, which was prevented by C5aRant.

Effect of C5a/C5aR signaling on actin reorganization in endothelial cells

The actin cytoskeleton maintains the structural integrity of the cell, and its reorganization could lead to increased vascular permeability. Rhodamine-phalloidin staining of monolayers fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 was performed to permit visualization of the actin filaments (Fig. 4). The addition of lupus serum caused increased F-actin stress fiber formation in the endothelial cell monolayer. In endothelial cells treated with control serum, F-actin staining was orderly. After the addition of lupus serum, the F-actin appearance was altered to an aggregated form. Pretreatment of cells with C5aRant was protective and significantly reduced the actin stress fiber formation.

Figure 4.

C5aR inhibition reduces stress fiber formation in endothelial cells. Monolayers of bEnd3 cells were treated with 5% control serum (left), lupus serum (center), or C5aRant (right) followed by lupus serum for 3 h. Typical patterns of Texas Red-phalloidin staining indicating actin rearrangement are seen in cells treated with lupus serum compared with cells treated with control serum. Pretreatment of cells with C5aRant significantly reduced actin rearrangement. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown. Nuclei were stained with DAPI.

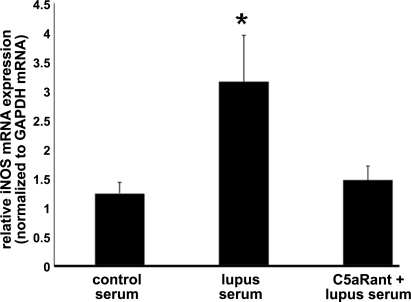

Role of C5aR on endothelial iNOS expression

iNOS is up-regulated in the vascular endothelium of both human SLE (59) and MRL/lpr mice (60). Therefore, we measured the iNOS mRNA expression in endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 5, the mRNA expression of iNOS as measured by qRT-PCR was increased in cells treated with lupus serum but prevented by pretreatment of cells with C5aRant (P<0.01). Our results demonstrate that the increased iNOS mRNA expression induced by lupus serum in bEnd3 cells is mediated, at least in part, through C5a/C5aR signaling.

Figure 5.

iNOS expression in endothelial cells is complement dependent. As shown by qRT-PCR, iNOS mRNA expression was increased in bEnd3 cells treated with serum from MRL/lpr mice compared with cells treated with serum from controls. Pretreatment of cells with C5aRant maintained iNOS expression at a level comparable to that in control cells. Data are means + sd from 5 experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. other groups.

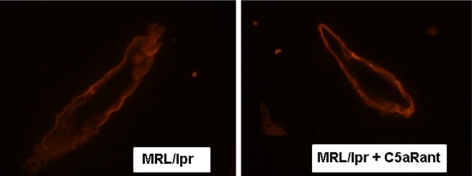

C5a regulates BBB integrity in MRL/lpr mice

To determine whether the effect of C5a on endothelial cells in culture could be translated in vivo, MRL/lpr mice were treated with C5aRant and the microvasculature in brain examined using a Zeiss confocal microscope at ×60 under oil. Laminin staining demonstrates that the walls of the microvessels in MRL/lpr mouse brain lost their membrane symmetry and were less well defined, whereas C5aR inhibition prevented the structural changes observed in the microvasculature (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

C5a alters integrity of BBB in MRL/lpr mice. MRL/lpr mice and MRL/lpr mice treated with C5aRant were euthanized at 20 wk of age. Brains were harvested, cryosectioned, immunostained, and observed using a Zeiss confocal microscope. Representative sections were stained with anti-laminin and observed at ×60 under oil. Lining of the vasculature was altered in MRL/lpr mouse brain, suggesting a potential loss of BBB integrity compared with the crisp vasculature lines in mice treated with C5aRant.

DISCUSSION

BBB is an important unit of the brain that maintains the internal milieu constant and protects the brain from circulating toxins and inflammatory cells (30, 31, 61). BBB damage occurs in several neuroinflammatory settings, including SLE (9, 62,63,64, 64, 64); however, because of the inaccessible nature of the brain, the mechanism by which this occurs remains unknown. Results of the present study suggest that one key candidate could be complement activation leading to C5a generation, followed by activation of the endothelium and actin rearrangement, thereby leading to BBB dysfunction.

The MRL/lpr mouse is a widely accepted lupus model that displays several disease similarities with humans (41, 50,51,52, 65). Our results using these mice demonstrate an altered BBB, because circulating IgG had immediate access to the brain parenchyma. Disruption of BBB has been proposed as a prelude to CNS damage because it would allow autoantibodies and infiltrating cells access to the brain (43, 66). The concentrations of several complement proteins, participating in different functions, are found to be altered in SLE (67, 68). We observed an increase in C5aR expression in these mice and in cultured endothelial cells treated with lupus serum.

In humans, circulating C5a has been observed to correlate with NP lupus (23, 69). Intrigued by these studies, we decided to examine the hypothesis that the detrimental effects of C5a/C5aR signaling on endothelial cells, the building blocks of the BBB, may be responsible for the loss of BBB integrity. The endothelial cell damage induced by C5a was evaluated using cultured endothelial cell monolayers. Lupus serum increased permeability through the monolayer, as estimated by TEER. Our results suggest that it could occur due to actin remodeling, as visualized by rhodamine-phalloidin staining of the monolayer. Pretreatment with the peptide antagonist C5aRant significantly reduced these alterations, indicating the important role of C5a/C5aR signaling in causing the pathology.

One of the mediators of cytoskeletal alterations in endothelial cells is ROS (70). Our results show that lupus serum increases ROS production in brain endothelial cells, and this increase is dependent on C5a/C5aR signaling. Both the antagonist C5aRant and the neutralizing antibody anti-C5a prevented increased ROS generation in the brain endothelial cells treated with lupus serum, indicating that the effect was specific to C5a/C5aR signaling. One hallmark of SLE in humans and the MRL/lpr mouse model is the up-regulation of iNOS in the vascular endothelium (59, 60). Our results show that the induction of iNOS mRNA is regulated by C5a/C5aR signaling. Furthermore, the product of iNOS (nitric oxide) is an inducer of ROS, and it interacts with ROS to cause further cellular damage (71). The contribution of iNOS signaling to the induction of ROS in SLE brain endothelial cells remains to be determined.

The anaphylatoxin C5a has been shown to have immune-regulatory role, and it mediates both chronic and acute inflammation (72, 73). Previous reports have revealed that after binding to C5aR, C5a activates multiple signaling proteins (74). However, the detailed signaling pathway has not been identified in brain endothelial cells. Our data suggest that C5a/C5aR induced cascade of events resulting in compromise of the BBB is dependent on increased expression of iNOS and ROS. It is possible that the results obtained in brain endothelial cells can be translated in vivo, because our studies show that C5aRant prevented the structural changes and loss of membrane symmetry in the brain microvessels in MRL/lpr mouse brain.

Taken together, these results suggest that C5a/C5aR signaling plays a key role in disrupting the BBB integrity through different cascades leading to altered iNOS, ROS, and actin reorganization. Therefore, our studies demonstrate that inhibition of C5aR is a potentially important treatment strategy for SLE. However, studies are required to determine the therapeutic potential of the antagonist in other neurodegenerative diseases because C5a can be protective in some settings, to define effective therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants R01DK055357 (to R.J.Q.) and P01 HL58064 (to J.G.N.G.).

References

- Boumpas D T, Fessler B J, Austin H A, III, Balow J E, Klippel J H, Lockshin M D. Systemic lupus erythematosus: emerging concepts. Part 2: Dermatologic and joint disease, the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, pregnancy and hormonal therapy, morbidity and mortality, and pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:42–53. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-1-199507010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumpas D T, Austin H A, III, Fessler B J, Balow J E, Klippel J H, Lockshin M D. Systemic lupus erythematosus: emerging concepts. Part 1: Renal, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and hematologic disease. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:940–950. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-12-199506150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M C. The lupus paradox. Nat Genet. 1998;19:3–4. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel T, Gladman D D, Urowitz M B. Neuropsychiatric lupus. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:325–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller S, Rondina J M, Li L M, Costallat L T, Cendes F. Cerebral and corpus callosum atrophy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2783–2789. doi: 10.1002/art.21271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brey R L, Holliday S L, Saklad A R, Navarrete M G, Hermosillo-Romo D, Stallworth C L, Valdez C R, Escalante A, del Rincón I, Gronseth G, Rhine C B, Padilla P, McGlasson D. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in lupus: prevalence using standardized definitions. Neurology. 2002;58:1214–1220. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denburg J A, Denburg S D, Carbotte R M, Long A A, Hanly J G. Nervous system involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Israel J Med Sci. 1988;24:754–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond B, Volpe B. On the track of neuropsychiatric lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2710–2712. doi: 10.1002/art.11278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta P T, Kowal C, DeGiorgio L A, Volpe B T, Diamond B. Immunity and behavior: antibodies alter emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:678–683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes G R. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:517–521. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.64.753.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum S R. Complement in central nervous system inflammation. Immunol Res. 2002;26:7–13. doi: 10.1385/IR:26:1-3:007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Eberhard H J, Schreiber R D. Molecular biology and chemistry of the alternative pathway of complement. Adv Immunol. 1980;29:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Eberhard H J. Molecular organization and function of the complement system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:321–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M C, Fischer M B. Complement and the immune response. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daha M R, van Kooten C, Roos A. Compliments from complement: A fourth pathway of complement activation? Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2006;21:3374–3376. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas I, Takahashi M, Fukuda A, Yamamoto N, Akatsu H, Baranyi L, Tateyama H, Yamamoto T, Okada N, Okada H. Complement C5a receptor-mediated signaling may be involved in neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. J Immunol. 2003;170:5764–5771. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flierl M A, Stahel P F, Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang M, Niederbichler A D, Hoesel L M, Touban B M, Morgan S J, Smith W R, Ward P A, Ipaktchi K. Inhibition of complement C5a prevents breakdown of the blood–brain barrier and pituitary dysfunction in experimental sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R12. doi: 10.1186/cc7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller T, Nolte C, Burger R, Verkhratsky A, Kettenmann H. Mechanisms of C5a and C3a complement fragment-induced [Ca2+]i signaling in mouse microglia. J Neurosci. 1997;17:615–624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00615.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayah S, Jauneau A C, Patte C, Tonon M C, Vaudry H, Fontaine M. Two different transduction pathways are activated by C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins on astrocytes. Mol Brain Res. 2003;112:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff T M, Crane J W, Proctor L M, Buller K M, Shek A B, de Vos K, Pollitt S, Williams H M, Shiels I A, Monk P N, Taylor S M. Therapeutic activity of C5a receptor antagonists in a rat model of neurodegeneration. FASEB J. 2006;20:1407–1417. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5814com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee P, Pasinetti G M. Complement anaphylatoxin C5a neuroprotects through mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent inhibition of caspase 3. J Neurochem. 2001;77:43–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiura H, Nonaka H, Revollo I S, Semba U, Li Y, Ota Y, Irie A, Harada K, Kehrl J H, Yamamoto T. Pro- and anti-apoptotic dual functions of the C5a receptor: involvement of regulator of G protein signaling 3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Lab Invest. 2009;89:676–694. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont H M, Hopkins P, Edelson H S, Kaplan H B, Ludewig R, Weissmann G, Abramson S. Complement activation during systemic lupus erythematosus. C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins circulate during exacerbations of disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1085–1089. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins P, Belmont H M, Buyon J, Philips M, Weissmann G, Abramson S B. Increased levels of plasma anaphylatoxins in systemic lupus erythematosus predict flares of the disease and may elicit vascular injury in lupus cerebritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:632–641. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J J, Zwingmann C, Quigg R. MRL/lpr mice have alterations in brain metabolism as shown with [(1)H-(13)C] NMR spectroscopy. Neurochem Int. 2005;47:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J J, Jacob A, Bao L, MacDonald R L, Quigg R J. Complement-dependent apoptosis and inflammatory gene changes in murine lupus cerebritis. J Immunol. 2005;175:8312–8319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J J, Jacob A, Vezina P, Sekine H, Gilkeson G S, Quigg R J. Absence of functional alternative complement pathway alleviates lupus cerebritis. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1691–1701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J J, Bao L, Jacob A, Kraus D M, Holers V M, Quigg R J. Administration of the soluble complement inhibitor, Crry-Ig, reduces inflammation and aquaporin 4 expression in lupus cerebritis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1639:169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott N J, Mendonca L L, Dolman D E. The blood–brain barrier in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2003;12:908–915. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu501oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davson H, Zlokovic B V, Rakic L, Segal M B. London: Macmillan; An Introduction to the Blood–Brain Barrier. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Davson H, Segal M B. New York, New York, USA: CRC; Physiology of the CSF and the Blood–Brain Barrier. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Foster J, Sakic B. Distribution and prevalence of leukocyte phenotypes in brains of lupus-prone mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;179:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James W G, Hutchinson P, Bullard D C, Hickey M J. Cerebral leucocyte infiltration in lupus-prone MRL/MpJ-fas lpr mice—roles of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and P-selectin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;144:299–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelweid C M, Johnson G C, Besch-Williford C L, Basler J, Walker S E. Inflammatory central nervous system disease in lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice: comparative histologic and immunohistochemical findings. J Neuroimmunol. 1991;35:89–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(91)90164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice A, Liu Y, Michaelis M L, Himes R H, Georg G I, Audus K L. Chemical modification of paclitaxel (Taxol) reduces P-glycoprotein interactions and increases permeation across the blood–brain barrier in vitro and in situ. J Med Chem. 2005;48:832–838. doi: 10.1021/jm040114b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanly J G, Robichaud J, Fisk J D. Anti-NR2 glutamate receptor antibodies and cognitive function in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1553–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGiorgio L A, Konstantinov K N, Lee S C, Hardin J A, Volpe B T, Diamond B. A subset of lupus anti-DNA antibodies cross-reacts with the NR2 glutamate receptor in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Med. 2001;7:1189–1193. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigg R J, Lo C F, Alexander J J, Sneed A E, III, Moxley G. Molecular characterization of rat Crry: widespread distribution of two alternative forms of Crry mRNA. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:362–367. doi: 10.1007/BF00179397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotze O, Muller-Eberhard H J. The alternative pathway of complement activation. Adv Immunol. 1976;24:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll M C. The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of Immunity Annu. Rev Immunol. 1998;16:545–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B H. Lessons in lupus: the mighty mouse. Lupus. 2001;10:589–593. doi: 10.1191/096120301682430140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballok D A. Neuroimmunopathology in a murine model of neuropsychiatric lupus. Brain Res Rev. 2007;54:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J J, Quigg R J. Systemic lupus erythematosus and the brain: what mice are telling us. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballok D A, Szechtman H, Sakic B. Taste responsiveness and diet preference in autoimmune MRL mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;140:119–130. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess D C, Taormina M, Thompson J, Sethi K D, Diamond B, Rao R, Chamberlain C R, Feldman D S. Cognitive and neurologic deficits in the MRL/lpr mouse: a clinicopathologic study. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:610–617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Sakic B, Szechtman H, Denburg J A. Effect of cyclophosphamide on leukocytic infiltration in the brain of MRL/lpr mice. Lupus. 1997;6:268–274. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakic B, Denburg J A, Denburg S D, Szechtman H. Blunted sensitivity to sucrose in autoimmune MRL-lpr mice: a curve-shift study. Brain Res Bull. 1996;41:305–311. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(96)00190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman H, Sakic B, Denburg J A. Behaviour of MRL mice: an animal model of disturbed behaviour in systemic autoimmune disease. Lupus. 1997;6:223–229. doi: 10.1177/096120339700600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballok D A, Woulfe J, Sur M, Cyr M, Sakic B. Hippocampal damage in mouse and human forms of systemic autoimmune disease. Hippocampus. 2004;14:649–661. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theofilopoulos A N, Kofler R, Singer P A, Dixon F J. Molecular genetics of murine lupus models. Adv Immunol. 1989;46:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60651-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theofilopoulos A N, Dixon F J. Murine models of systemic lupus erythematosus. Adv Immunol. 1985;37:269–390. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon F J, Andrews B S, Eisenberg R A, McConahey P J, Theofilopoulos A N, Wilson C B. Etiology and pathogenesis of a spontaneous lupus-like syndrome in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 1978;21:S64–S67. doi: 10.1002/art.1780210909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R C, Morris A P, O'Neil R G. Tight junction protein expression and barrier properties of immortalized mouse brain microvessel endothelial cells. Brain Res. 2007;1130:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coisne C, Dehouck L, Faveeuw C, Delplace Y, Miller F, Landry C, Morissette C, Fenart L, Cecchelli R, Tremblay P, Dehouck B. Mouse syngenic in vitro blood–brain barrier model: a new tool to examine inflammatory events in cerebral endothelium. Lab Invest. 2005;85:734–746. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbiev T, Birukova A, Liu F, Nurmukhambetova S, Gerthoffer W T, Garcia J G, Verin A D. p38 MAP kinase-dependent regulation of endothelial cell permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L911–L918. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00372.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek S M, Garcia J G. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1487–1500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton A S, Abbott N J. Bradykinin increases permeability by calcium and 5-lipoxygenase in the ECV304/C6 cell culture model of the blood–brain barrier. Brain Res. 2002;953:157–169. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Ramachandrarao S P, Siva S, Valancius C, Zhu Y, Mahadev K, Toh I, Goldstein B J, Woolkalis M, Sharma K. Reactive oxygen species production via NADPH oxidase mediates TGF-beta-induced cytoskeletal alterations in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F816–F825. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont H M, Levartovsky D, Goel A, Amin A, Giorno R, Rediske J, Skovron M L, Abramson S B. Increased nitric oxide production accompanied by the up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelium from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1810–1816. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J B, Granger D L, Pisetsky D S, Seldin M F, Misukonis M A, Mason S N, Pippen A M, Ruiz P, Wood E R, Gilkeson G S. The role of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of spontaneous murine autoimmune disease: increased nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthase expression in MRL-lpr/lpr mice, and reduction of spontaneous glomerulonephritis and arthritis by orally administered NG-monomethyl-l-arginine. J Exp Med. 1994;179:651–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossinsky A S, Shivers R R. Structural pathways for macromolecular and cellular transport across the blood–brain barrier during inflammatory conditions. Review. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:535–564. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond B, Kowal C, Huerta P T, Aranow C, Mackay M, DeGiorgio L A, Lee J, Triantafyllopoulou A, Cohen-Solal J, Volpe B T. Immunity and acquired alterations in cognition and emotion: lessons from SLE. Adv Immunol. 2006;89:289–320. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(05)89007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek S J, Graus F, Elkon K B. Autoantibodies in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1090–1097. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramson S, Belmont H M, Hopkins P, Buyon J, Winchester R, Weissmann G. Complement activation and vascular injury in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brey R L, Sakic B, Szechtman H, Denburg J A. Animal models for nervous system disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;823:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal C, DeGiorgio L A, Lee J Y, Edgar M A, Huerta P T, Volpe B T, Diamond B. Human lupus autoantibodies against NMDA receptors mediate cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19854–19859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608397104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora V, Verma J, Dutta R, Marwah V, Kumar A, Das N. Reduced complement receptor 1 (CR1, CD35) transcription in systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:449–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongen P J, Doesburg W H, Ibrahim-Stappers J L, Lemmens W A, Hommes O R, Lamers K J. Cerebrospinal fluid C3 and C4 indexes in immunological disorders of the central nervous system. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;101:116–121. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2000.101002116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao L, Osawe I, Puri T, Lambris J D, Haas M, Quigg R J. C5a promotes development of experimental lupus nephritis which can be blocked with a specific receptor antagonist. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2496–2506. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu T, Ramachandrarao S P, Siva S, Valancius C, Zhu Y, Mahadev K, Toh I, Goldstein B J, Woolkalis M, Sharma K. Reactive oxygen species production via NADPH oxidase mediates TGF-beta-induced cytoskeletal alterations in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F816–F825. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00024.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G C, Borutaite V. Interactions between nitric oxide, oxygen, reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:953–956. doi: 10.1042/BST0340953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo R F, Ward P A. Role of C5a in inflammatory responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:821–852. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawlisch H, Belkaid Y, Baelder R, Hildeman D, Gerard C, Kohl J. C5a negatively regulates toll-like receptor 4-induced immune responses. Immunity. 2005;22:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pytel P, Alexander J J. Pathogenesis of septic encephalopathy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:283–287. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832b3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]