Abstract

Background

Artificial duplicates from pyrosequencing reads may lead to incorrect interpretation of the abundance of species and genes in metagenomic studies. Duplicated reads were filtered out in many metagenomic projects. However, since the duplicated reads observed in a pyrosequencing run also include natural (non-artificial) duplicates, simply removing all duplicates may also cause underestimation of abundance associated with natural duplicates.

Results

We implemented a method for identification of exact and nearly identical duplicates from pyrosequencing reads. This method performs an all-against-all sequence comparison and clusters the duplicates into groups using an algorithm modified from our previous sequence clustering method cd-hit. This method can process a typical dataset in ~10 minutes; it also provides a consensus sequence for each group of duplicates. We applied this method to the underlying raw reads of 39 genomic projects and 10 metagenomic projects that utilized pyrosequencing technique. We compared the occurrences of the duplicates identified by our method and the natural duplicates made by independent simulations. We observed that the duplicates, including both artificial and natural duplicates, make up 4-44% of reads. The number of natural duplicates highly correlates with the samples' read density (number of reads divided by genome size). For high-complexity metagenomic samples lacking dominant species, natural duplicates only make up <1% of all duplicates. But for some other samples like transcriptomic samples, majority of the observed duplicates might be natural duplicates.

Conclusions

Our method is available from http://cd-hit.org as a downloadable program and a web server. It is important not only to identify the duplicates from metagenomic datasets but also to distinguish whether they are artificial or natural duplicates. We provide a tool to estimate the number of natural duplicates according to user-defined sample types, so users can decide whether to retain or remove duplicates in their projects.

Background

Metagenomics is a new field that studies the microbes under different environmental conditions such as ocean, soil, human distal gut, and many others [1-6]. Using culture-independent genomic sequencing technologies, metagenomics provides a more global and less biased view of an entire microbial community than the traditional isolated genomics. The earlier metagenomic studies were largely carried out with Sanger sequencing, but recently, more studies [7-9] were performed with the new breaking through next-generation sequencing technologies [10]. Today, the pyrosequencing by Roche's 454 life science serves as a dominant sequencing platform in metagenomics.

However, it is known that the 454 sequencers produce artificially duplicated reads, which might lead to misleading conclusions. Exact duplicates sometimes were removed before data analyses [7]. Recently, in the study by Gomez-Alvarez et al [11], nearly identical duplicates, the reads that begin at the same position but may vary in length or bear mismatches, were also classified as artifacts. Exact and nearly identical duplicates may make up 11~35% of the raw reads.

In metagenomics, the amount of reads is used as an abundance measure, so artificial duplicates will introduce overestimation of abundance of taxon, gene, and function. Duplicated reads observed in a pyrosequencing run include not only artificial duplicates but also natural duplicates - reads from the same origin that start at the same genomic position by chance. Therefore, simply removing all duplicates might also cause underestimation of abundance associated with naturally duplicated reads. The occurrence of natural duplicates can be very low for metagenomic samples lacking dominant species [11], or can be very high for other samples like transcriptomic samples (results in this study). So it is important not only to identify the duplicates, but also to distinguish whether they are artificial or natural duplicates.

Exactly identical sequences can be easily found, but identification of non-exact duplicates requires sophisticated algorithms to process the massive sequence comparisons between reads. In Gomez-Alvarez et al's study [11], the duplicates were identified by first clustering the reads at 90% sequence identity using cd-hit program [12-14] and then parsing the clustering results.

In this study, we first implemented a method for identification of exact and nearly identical duplicates from pyrosequencing reads. As the original developers of cd-hit, we reengineered cd-hit into a new program that can process the duplicates more effectively than the original program. This method can process a typical 454 dataset in ~10 minutes; it also provides a consensus sequence for each group of duplicates. Secondly, we validated this method using the underlying raw reads from a list of genome projects utilizing pyrosequencing technology. We compared the occurrences of the duplicates identified by our method and the natural duplicates made by independent simulations. Lastly, we studied duplicates for several metagenomic samples and estimated their natural duplicates under different situations.

Results and discussion

Program for identification of duplicates

We implemented a computer program called cdhit-454 to identify duplicated reads by reengineering our ultra-fast sequence clustering algorithm cd-hit [12-14]. The algorithm and other details of cdhit-454 are introduced in the Methods section. Briefly, we constrained cdhit-454 to find exact duplicates and nearly identical duplicates that start at the same position and are within the user-defined level of mismatches (insertions, deletions, and substitutions). We allow mismatches in order to tolerate sequencing errors. The default parameters of mismatches are based on the pyrosequencing error model derived in this study. We provide a tool in cdhit-454 to build a consensus sequence for each group of duplicates. The model used for consensus generation is also described in the Methods section. Cdhit-454 software and web server are available at http://cd-hit.org/.

Duplicated reads of genomic datasets

We tested and validated cdhit-454 with data from pyrosequencing-based genome projects where both the complete genomes and the underlying raw reads are available from NCBI at RefSeq and Short Read Archive (SRA). For a project with multiple sequencing runs, only the run with the most reads was selected. We identified 39 such genome projects on September 2009, with 15 from GS-20 and 24 from GS-FLX platform (including 1 GS-FLX Titanium). The details of the 39 projects, including their project identifiers, SRA accession numbers, genome sizes, GC contents, and other calculated results, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genome projects with full genomes from Refseq and pyrosequencing reads from Short Read Archive

| IDa | SRA Studya |

SRA Runa |

Platform | Genome | Genome size (Mbp) |

GC (%) |

Number reads |

Read Densityb |

% of total Duplicates |

% of natural Duplicates (σ d) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20067 | SRP000091 | SRR000351 | GS_20 | NC_010741 | 1.13946 | 52 | 529181 | 0.4644 | 13.585 | 5.032 | (0.030) |

| 20739 | SRP000868 | SRR017616 | GS_FLX | NC_013170 | 1.61780 | 50 | 513712 | 0.3175 | 17.751 | 4.999 | (0.022) |

| 29525 | SRP000571 | SRR013433 | GS_FLX | NC_013124 | 2.15816 | 68 | 570098 | 0.2641 | 9.938 | 4.464 | (0.034) |

| 19265 | SRP000036 | SRR000223 | GS_20 | NC_010085 | 1.64526 | 34 | 429372 | 0.2609 | 12.120 | 4.418 | (0.026) |

| 19981 | SRP000204 | SRR001584 | GS_20 | NC_010830 | 1.88436 | 35 | 399515 | 0.2120 | 26.027 | 4.293 | (0.030) |

| 20655 | SRP000207 | SRR001568 | GS_20 | NC_012803 | 2.50109 | 72 | 528437 | 0.2112 | 9.734 | 4.099 | (0.032) |

| 20833 | SRP000867 | SRR017612 | GS_FLXe | NC_013174 | 2.74965 | 58 | 574027 | 0.2087 | 16.266 | 3.745 | (0.027) |

| 18819 | SRP000035 | SRR000219 | GS_20 | NC_009637 | 1.77269 | 33 | 332809 | 0.1877 | 15.145 | 3.664 | (0.024) |

| 29443 | SRP000895 | SRR017790 | GS_FLX | NC_013166 | 2.85207 | 43 | 529344 | 0.1855 | 16.017 | 3.044 | (0.025) |

| 29419 | SRP000560 | SRR013388 | GS_FLX | NC_012785 | 2.30212 | 41 | 416146 | 0.1807 | 9.537 | 3.025 | (0.031) |

| 19543 | SRP000205 | SRR001565 | GS_20 | NC_010483 | 1.87769 | 46 | 321938 | 0.1714 | 25.373 | 2.886 | (0.038) |

| 29381 | SRP000558 | SRR013382 | GS_FLX | NC_011832 | 2.92292 | 55 | 461295 | 0.1578 | 8.526 | 2.911 | (0.024) |

| 29403 | SRP000584 | SRR013477 | GS_FLX | NC_013162 | 2.61292 | 39 | 400460 | 0.1532 | 11.796 | 2.549 | (0.021) |

| 29177 | SRP000442 | SRR007446 | GS_FLX | NC_011901 | 3.46455 | 65 | 438386 | 0.1265 | 14.140 | 2.239 | (0.023) |

| 29493 | SRP000569 | SRR013431 | GS_FLX | NC_011883 | 2.87344 | 58 | 362855 | 0.1262 | 11.171 | 2.204 | (0.023) |

| 29175 | SRP000928 | SRR018125 | GS_FLX | NC_011661 | 1.85556 | 33 | 225795 | 0.1216 | 6.209 | 2.151 | (0.021) |

| 27731 | SRP000397 | SRR006411 | GS_FLX | NC_011769' | 4.04030 | 67 | 488823 | 0.1209 | 18.793 | 2.073 | (0.020) |

| 31289 | SRP000919 | SRR018042 | GS_FLX | NC_012917 | 4.86291 | 51 | 517593 | 0.1064 | 3.211 | 1.948 | (0.037) |

| 20635 | SRP000049 | SRR000266 | GS_20 | NC_011666 | 4.30543 | 63 | 401125 | 0.0931 | 10.364 | 1.943 | (0.022) |

| 31295 | SRP000921 | SRR018051 | GS_FLX | NC_012912 | 4.81385 | 54 | 441287 | 0.0916 | 6.938 | 1.941 | (0.019) |

| 29527 | SRP000893 | SRR017783 | GS_FLX | NC_013173 | 3.94266 | 58 | 352814 | 0.0894 | 8.356 | 1.926 | (0.022) |

| 20039 | SRP000209 | SRR001574 | GS_FLXf | NC_010524 | 4.90940 | 68 | 422674 | 0.0860 | 8.566 | 1.785 | (0.023) |

| 19701 | SRP000046 | SRR000255 | GS_20 | NC_010644 | 1.64356 | 39 | 136514 | 0.0830 | 5.922 | 1.744 | (0.022) |

| 19743 | SRP000045 | SRR000254 | GS_20 | NC_011145 | 5.06163 | 74 | 409136 | 0.0808 | 7.464 | 1.739 | (0.019) |

| 20095 | SRP000054 | SRR000278 | GS_20 | NC_011891 | 5.02933 | 74 | 404796 | 0.0804 | 8.363 | 1.515 | (0.022) |

| 30681 | SRP000922 | SRR018054 | GS_FLX | NC_012947 | 4.57094 | 50 | 367491 | 0.0803 | 11.324 | 1.449 | (0.018) |

| 21119 | SRP000208 | SRR001573 | GS_FLXf | NC_012032 | 5.26895 | 56 | 392222 | 0.0744 | 10.026 | 1.321 | (0.025) |

| 18637 | SRP000034 | SRR000215 | GS_20 | NC_010172 | 5.47115 | 68 | 395973 | 0.0723 | 12.998 | 1.306 | (0.016) |

| 20167 | SRP000053 | SRR000277 | GS_20 | NC_011004 | 5.74404 | 64 | 413261 | 0.0719 | 14.572 | 1.248 | (0.022) |

| 19989 | SRP000211 | SRR001579 | GS_20 | NC_010571 | 5.95761 | 65 | 378824 | 0.0635 | 5.484 | 1.145 | (0.023) |

| 19449 | SRP000043 | SRR000248 | GS_20 | NC_011768 | 6.51707 | 54 | 395672 | 0.0607 | 16.631 | 1.108 | (0.018) |

| 33873 | SRP000554 | SRR013372 | GS_FLX | NC_012691 | 3.47129 | 49 | 191873 | 0.0552 | 43.680 | 1.001 | (0.025) |

| 27951 | SRP000587 | SRR013487 | GS_FLX | NC_013132 | 9.12735 | 45 | 496792 | 0.0544 | 15.017 | 0.283 | (0.033) |

| 20827 | SRP000582 | SRR013470 | GS_FLX | NC_012669 | 4.66918 | 73 | 246279 | 0.0527 | 4.140 | 0.295 | (0.023) |

| 33069 | SRP000920 | SRR018045 | GS_FLX | NC_012880 | 4.67945 | 55 | 226208 | 0.0483 | 13.585 | 5.032 | (0.030) |

| 19705 | SRP000576 | SRR013446 | GS_FLX | NC_013093 | 8.24814 | 73 | 381851 | 0.0462 | 17.751 | 4.999 | (0.022) |

| 29975 | SRP000443 | SRR013137 | GS_FLX | NC_011992 | 3.79657 | 66 | 161655 | 0.0425 | 9.938 | 4.464 | (0.034) |

| 17265 | SRP000067 | SRR000311 | GS_20 | NC_008369 | 1.89572 | 32 | 28221 | 0.0148 | 12.120 | 4.418 | (0.026) |

| 20729 | SRP000267 | SRR004103 | GS_FLX | NC_012918 | 4.74581 | 60 | 22822 | 0.0048 | 26.027 | 4.293 | (0.030) |

aProject IDs, SRA study accessions, and SRA run accessions are from NCBI Short Read Archive at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi.

bRead Density is the number of reads divided by the genome length.

dσ is the standard deviation, which is based on the results of 100 simulations (see the "Duplicated reads of genomic datasets" section).

eThe platform provided by SRA is GS_FLX, and the read length (~400 bp) suggests GS_FLX Titanium.

fThe platform provided by SRA is GS_20, but the read length (~200 bp) suggests GS_FLX.

For each genome project, we applied cdhit-454 on the raw reads to identify the duplicates, which include both artificial and natural duplicates. The number of natural duplicates was empirically estimated by applying cdhit-454 on simulated reads, which are fragments randomly cut from the complete genomes.

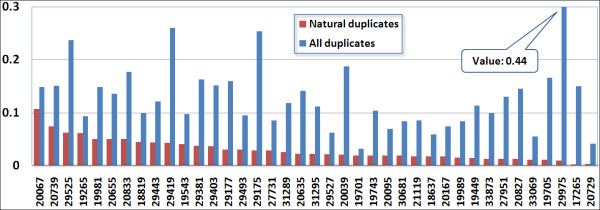

A simulated reads set and the experimental raw reads set in each genome project have the exactly the same number of sequences of exactly the same lengths. We generated 1000 sets of simulated reads for each genome project and selected 100 sets that are most similar to its corresponding raw reads in GC content. We further introduced sequencing errors (insertions, deletions, and substitutions) to the simulated reads according to the error model derived in this study (Table 2, 3). These processes made the simulated read sets as similar as possible to the real reads set, except that the former only contains natural duplicates. Using cdhit-454, we identified the duplicates for the 100 sets of simulated reads of each project and calculated the average duplicate ratio and the standard deviations. Figure 1 shows the ratio of all duplicates and the average natural duplicates for these 39 projects. The results and the standard deviations are also available in Table 1.

Table 2.

pyrosequencing error rate of GS-20 platform

| Percentage by error types (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project IDa | Error Rateb | Insertion | Deletion | Substitution |

| 17265 | 0.00774 | 27.06 | 17.28 | 55.67 |

| 18637 | 0.00250 | 60.94 | 22.24 | 16.82 |

| 18819 | 0.01194 | 36.91 | 19.62 | 43.47 |

| 19265 | 0.00893 | 41.32 | 14.51 | 44.18 |

| 19449 | 0.00569 | 38.98 | 20.23 | 40.79 |

| 19543 | 0.00522 | 49.07 | 18.97 | 31.96 |

| 19701 | 0.01097 | 32.89 | 17.93 | 49.18 |

| 19743 | 0.00287 | 57.51 | 28.29 | 14.21 |

| 19981 | 0.00530 | 28.85 | 17.73 | 53.42 |

| 19989 | 0.00216 | 54.29 | 22.33 | 23.38 |

| 20067 | 0.00679 | 46.67 | 12.15 | 41.19 |

| 20095 | 0.00216 | 50.48 | 28.75 | 20.77 |

| 20167 | 0.00157 | 53.65 | 26.70 | 19.65 |

| 20635 | 0.00231 | 57.82 | 18.25 | 23.93 |

| 20655 | 0.00211 | 51.31 | 29.94 | 18.75 |

| Average | 0.00522 | 45.85 | 20.99 | 33.16 |

aProject ID is the same as in Table 1.

bError rate is calculated for aligned reads as the number of errors (insertion, deletion, and substitution) divided by the number of bases of reads.

Table 3.

pyrosequencing error rate of GS-GLX platform

| Percentage by error types (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project IDa | Error Rateb | Insertion | Deletion | Substitution |

| 20039 | 0.00196 | 51.35 | 26.49 | 22.16 |

| 21119 | 0.00360 | 60.85 | 22.18 | 16.97 |

| 19705 | 0.00189 | 53.24 | 31.03 | 15.73 |

| 20729 | 0.00413 | 19.49 | 23.86 | 56.65 |

| 20739 | 0.00244 | 55.33 | 24.00 | 20.66 |

| 20827 | 0.00122 | 46.32 | 32.48 | 21.20 |

| 20833 | 0.00540 | 53.55 | 37.38 | 9.07 |

| 27731 | 0.00280 | 34.28 | 19.11 | 46.61 |

| 27951 | 0.00377 | 42.11 | 14.75 | 43.14 |

| 29175 | 0.00909 | 40.33 | 16.96 | 42.72 |

| 29177 | 0.00645 | 68.49 | 16.74 | 14.76 |

| 29381 | 0.00607 | 59.57 | 17.15 | 23.29 |

| 29403 | 0.01035 | 58.48 | 19.48 | 22.04 |

| 29419 | 0.00689 | 39.99 | 17.75 | 42.26 |

| 29443 | 0.00396 | 39.97 | 16.41 | 43.62 |

| 29493 | 0.00741 | 46.69 | 17.81 | 35.50 |

| 29525 | 0.00196 | 55.62 | 28.66 | 15.72 |

| 29527 | 0.00613 | 57.44 | 21.91 | 20.66 |

| 29975 | 0.00391 | 57.17 | 19.47 | 23.36 |

| 30681 | 0.00605 | 60.41 | 20.04 | 19.55 |

| 31289 | 0.00389 | 53.18 | 17.61 | 29.21 |

| 31295 | 0.00444 | 58.20 | 15.56 | 26.24 |

| 33069 | 0.00508 | 60.19 | 18.06 | 21.76 |

| 33873 | 0.00540 | 63.31 | 16.22 | 20.47 |

| Average | 0.00476 | 51.48 | 21.30 | 27.22 |

aProject ID is same as in Table 1.

bError rate is calculated for aligned reads as the number of errors (insertion, deletion, and substitution) divided by the number of bases of reads.

Figure 1.

Ratio of all duplicates and average natural duplicates to all reads from genome projects. X-axis is project identifier of datasets, which are ordered by decreasing read density (number of reads divided by genome size). Y-axis is the ratio of duplicated reads to all reads.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the duplicates make up to 4-44% of reads. We observed that the ratio of natural duplicates, which ranges from 1-11%, highly correlates with the read density (number of reads divided by genome size) with a Pearson correlation factor of 0.99. The ratio of artificial duplicates (subtract natural duplicates from all duplicates) varies from 3-42%. On average, artificial duplicates make up 74% of all duplicates, and this percentage varies from 28% to 98% (first left and second right projects in Figure 1). Artificial duplicates happen randomly without observed correlation with the sample's GC content, genome size, or platform (GS-20 or GS-FLX).

Here, we define the sensitivity and specificity for the evaluation of duplicate identification. Within the simulated datasets, the reads that start at the same position are considered as true duplicates. The sensitivity of a method is the ratio of predicted true duplicates by this method to all true duplicates. The specificity is the ratio of predicted true duplicates to all predictions by this method. The averaged sensitivity and specificity for the 39 datasets are both ~98.0% using the default parameters of cdhit-454.

Pyrosequencing errors

The original 454 publication reported an error rate at ~4% [15]. But later studies yielded much higher accuracy. For example, Huse et al. concluded an error rate at ~0.5% for GS20 system [16]. Quinlan et al. provided a similar error rate at about ~0.4% [17].

Accurate estimation of the pyrosequencing error rate is very important for this study, because we use the error rate to optimize the parameters for cdhit-454 program to identify the duplicated reads with sequencing errors. The error model is also used to guide the generation of sequencing errors in the simulated datasets in above analysis. Therefore, we re-evaluated the pyrosequencing error rate using the data from Table 1.

We used Megablast [18] with the default parameters to align the raw reads back to the corresponding reference genomes. Only the reads with at least 90% of the length aligned were selected to calculate the error rates. Other reads were treated as from contamination material, and therefore discarded. The error rates and fractions by error types (insertion, deletion, and substitution) for all projects are shown in Table 2 for GS-20 and Table 3 for GS-FLX.

We found that the error rate (number of errors divided by total bases) for pyrosequencing is from 0.4% to 0.5%. About 75% of the reads have no error; and about another 20% of the reads have ≤ 2% errors. If the sequencing error rate is 2%, two reads may have up to 4% mismatches. We set the default mismatch cutoff at 4% for cdhit-454 so that about 95% of reads can be covered. We examined several mismatch cutoffs from 95% to 98% on the simulated datasets; the 96% cutoff gave the best sensitivity and specificity. The mismatch cutoff parameter in cdhit-454 is a user-configurable parameter. If the low-quality reads are already filtered out, a higher cutoff such as 98% may be used.

Duplicated reads of metagenomic datasets

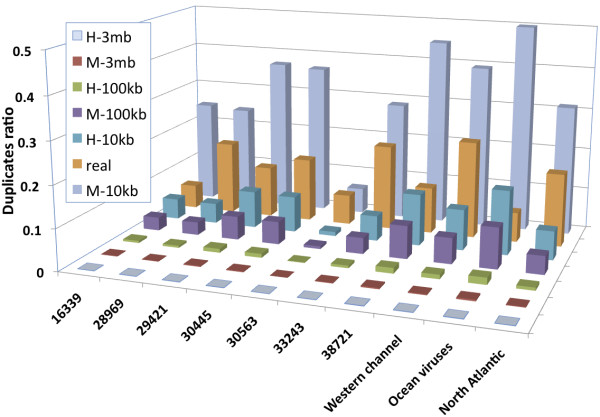

We studied the pyrosequencing reads for 10 metagenomic datasets (Table 4) of different environments from NCBI SRA or from CAMERA metagenomic project http://camera.calit2.net. We identified their duplicates with cdhit-454 (Figure 2). The duplicates make up 5-23% of reads. As concluded earlier in this study, the quantity of natural duplicates of metagenomic samples depends on the read density of their individual species, and therefore can vary significantly. Since the exact species composition and genome sequences are unknown for metagenomic samples, we could not calculate the amount of natural duplicates as we did for the genome projects. So, we simulated the occurrence of natural duplicates under several hypothetical sample types.

Table 4.

Metagenomic datasets used in this study

| % of natural duplicates under hypothetical sample types |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-complexityb | Moderate-complexityc | |||||||||

| Project/Samplea | Environment | Platform | Number Reads |

% of total Duplicates |

3 mb | 100 kb | 10 kb | 3 mb | 100 kb | 10 kb |

| 16339/SRR000905 | Marine | GS_20 | 208633 | 5.74 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 4.98 | 0.10 | 3.22 | 24.88 |

| 28969/SRR000674 | Coastal water | GS_FLX | 201671 | 17.65 | 0.02 | 0.51 | 4.87 | 0.10 | 3.13 | 24.27 |

| 29421/SRR001308 | Waste water | GS_FLX | 378601 | 12.39 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 8.94 | 0.20 | 5.65 | 37.09 |

| 30445/SRR001663 | Marine | GS_FLX | 369811 | 15.39 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 8.68 | 0.19 | 5.49 | 36.53 |

| 30563/SRR001669 | Human gut | GS_20 | 41649 | 7.26 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.65 | 6.16 |

| 33243/SRR006907 | Freshwater | GS_FLX | 255722 | 20.57 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 6.07 | 0.13 | 3.88 | 28.71 |

| 38721/SRR023845 | Phyllosphere | GS_FLX | 543285 | 11.17 | 0.05 | 1.33 | 12.41 | 0.29 | 7.93 | 45.07 |

| Western channel/Apr_Day_gDNA | Saline water | Titanium | 421004 | 23.38 | 0.04 | 1.04 | 9.80 | 0.20 | 6.23 | 39.42 |

| Ocean viruses/Arctic_Shotgun | Ocean viruses | GS_20 | 688590 | 7.14 | 0.05 | 1.67 | 15.46 | 0.36 | 9.86 | 50.15 |

| North Atlantic/BATS-174-2 | Ocean gyre | GS_20 | 288735 | 17.56 | 0.02 | 0.73 | 6.92 | 0.16 | 4.43 | 31.24 |

aDatasets are either from NCBI Short Read Archive with project IDs and run accession numbers at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/sra.cgi or from CAMERA with project and sample names at http://camera.calit2.net.

bHigh-, cmoderate-complexity microbial (or viral) environment with average genome length of 3 mb, 100 kb, and 10 kb

Figure 2.

Ratio of all duplicates and natural duplicates under different hypothetical types for metagenomic samples. X-axis is the name or project identifier of metagenomic samples. For the real metagenomic dataset, the duplicates include both artificial and natural duplicates. For other hypothetical sample types, the duplicates are natural duplicates.

Metagenomic samples are roughly grouped into low-, moderate-, and high-complexity samples, which represent samples dominated by a single near-clonal population, samples with more than one dominant species, and those lacking dominant populations respectively[19]. We constructed 6 hypothetical sample types: M-3 mb, M-100 kb, M-10 kb, H-3 mb, H-100 kb, and H-10 kb; here the name of a sample type starts with M or H (for moderate- or high-complexity) followed by the average genome size. Therefore, M-3 mb represents a moderate-complexity microbial sample with 3 MB genomes; and H-10 kb may represent a high-complexity small viral sample. We assumed that each hypothetical sample contained 100 different genomes of certain length. Given a set of reads, in order to calculate the natural duplicates under a high-complexity hypothetical sample type, we assigned these reads to the 100 genomes randomly at arbitrary positions on either strand. For a moderate-complexity type, 50% of the reads were randomly assigned to 3 dominant genomes, and other reads were randomly mapped to the remaining 97 low-abundance genomes. The natural duplicates were identified by comparing the mapping coordinates. We applied this method to the 10 metagenomic datasets to calculate the ratio of their natural duplicates under different hypothetical sample types (Figure 2 and Table 4).

From Figure 2, we can see that if these metagenomic samples match H-3 mb, M-3 mb, and H-100 kb, their natural duplicates only make up 0.2%, 1.5%, and 7.4% of all duplicates on average; so it is appropriate to filter out the duplicates. However, if a metagenomic sample matches other types, the number of anticipated natural duplicates may be similar or even larger than the artificial duplicates.

Here, we want to discuss a particular type of samples - metatranscriptomic samples. Similar to metagenomics, metatranscriptomics is a field that studies the microbial gene expression via sequencing of the total RNAs extracted directly from environments. Recent metatranscriptomic studies [8,20,21] were performed with pyrosequencing. Since most microbial transcript sequences are only 102~104 bases in length and one transcript can have many copies in a cell, so the read density of metatranscriptomic samples is several orders of magnitude higher than the read density of metagenomic samples. It is expected that metatranscriptomic samples have high occurrence of natural duplicates. For example, 61% of reads in the mRNA samples from [21] are found as duplicates by cdhit-454; it is reasonable to believe most of them are natural duplicates and therefore should be kept for abundance analysis.

Conclusions

In this study, we present an effective method to identify exact and nearly identical duplicated sequences from pyrosequencing reads. But since the identified duplicates contain natural duplicates, it is important to estimate the proportion of natural duplicates. In the cdhit-454 package, we provide a tool to estimate the number of natural duplicates under any hypothetical sample type defined by users, so users can decide whether to retain or remove duplicates in their projects.

Methods

Algorithm of cdhit-454

In cdhit-454, we use the original clustering algorithm of cd-hit [12-14]. Briefly, reads are first sorted in decreasing length. The longest one becomes the seed of the first cluster. Then, each remaining sequence is compared to the seeds of all existing clusters. If the similarities with existing seeds meet pre-defined criteria, it is grouped into the most similar cluster. Otherwise, a new cluster is defined with the sequence as the seed. The pre-defined criteria includes: (1) they start at the same position; (2) their lengths can be different, but shorter one must be fully aligned with the longer one (the seed); (3) they can only have 4% mismatches (insertion, deletion, and substitution); and (4) only 1 base is allowed per insertion or deletion. Here, (3) and (4) are set according to the pyrosequencing error rate derived in this study (Result and discussion) and can be adjusted by users.

Generate consensus

We provide a program to build a consensus sequence for each group of duplicates. This tool takes the output of cdhit-454 and original FASTA or FASTQ file. It builds a multiple sequence alignment for each group of duplicates with program ClustalW[22], then generate consensus based on following model:

If a FASTA file is used, the most frequent symbol in each column of the alignment is used as the consensus, and then symbols representing gaps are removed from the consensus sequence. If a FASTQ file is used, the quality score for each base is converted into its error probability to improve the consensus generation.

In a column of a multiple alignment, the count for gaps is calculated as the real count, while the counts for letters {'A','C','G','T'} are "corrected" by the error probabilities, with contribution from letter 'N' which is not counted for itself. Suppose there are M letters in one position of a M-sequence alignment: b(i)∈ {'A', 'C', 'G', 'T'}, i = 1, ..., M , with quality scores si and error probabilities pi, where,

The count c(α) for α∈ {'A', 'C', 'G', 'T'} is calculated as,

|

where δ(x, y) is a function that takes value one when x equals to y, and take zero otherwise. Namely, if the bi is α, a fraction count of 1-pi is added for letter α, and a fraction count of pi is equally distributed on the other letters among {'A', 'C', 'G', 'T'}, which reflects the nature of the error probability.

Then for each column, if there is a dominant letter or gap with frequency equal to or greater than 0.5, this dominant symbol is used in that column in the consensus, otherwise letter 'N' is used, and then symbols representing gaps are removed from the consensus sequence.

Estimate natural duplicates in hypothetical metagenomic samples

We provide a program to estimate the number of natural duplicates under any hypothetical sample type. A user provides the number of reads and the size and abundance of genomes in a hypothetical sample. Our tool gives the number of simulated natural duplicates.

Authors' contributions

BN designed and carried out the study, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. LF implemented the method and wrote the manuscript. SS prepared the datasets and analyzed the results. WL conceived of the study, implemented the method and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Beifang Niu, Email: bniu@ucsd.edu.

Limin Fu, Email: l2fu@ucsd.edu.

Shulei Sun, Email: s2sun@ucsd.edu.

Weizhong Li, Email: liwz@sdsc.edu.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Award Number R01RR025030 to WL from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCRR or the National Institutes of Health. SS was supported by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through the CAMERA project.

References

- Rusch DB, Halpern AL, Sutton G, Heidelberg KB, Williamson S, Yooseph S, Wu D, Eisen JA, Hoffman JM, Remington K. The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling Expedition: Northwest Atlantic through Eastern Tropical Pacific. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(3):e77. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, Halpern AL, Rusch D, Eisen JA, Wu D, Paulsen I, Nelson KE, Nelson W. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science. 2004;304(5667):66–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1093857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tringe SG, von Mering C, Kobayashi A, Salamov AA, Chen K, Chang HW, Podar M, Short JM, Mathur EJ, Detter JC. Comparative metagenomics of microbial communities. Science. 2005;308(5721):554–557. doi: 10.1126/science.1107851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, Gordon JI, Relman DA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Nelson KE. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson GW, Chapman J, Hugenholtz P, Allen EE, Ram RJ, Richardson PM, Solovyev VV, Rubin EM, Rokhsar DS, Banfield JF. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature. 2004;428(6978):37–43. doi: 10.1038/nature02340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong EF, Preston CM, Mincer T, Rich V, Hallam SJ, Frigaard NU, Martinez A, Sullivan MB, Edwards R, Brito BR. Community genomics among stratified microbial assemblages in the ocean's interior. Science. 2006;311(5760):496–503. doi: 10.1126/science.1120250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinsdale EA, Edwards RA, Hall D, Angly F, Breitbart M, Brulc JM, Furlan M, Desnues C, Haynes M, Li L. Functional metagenomic profiling of nine biomes. Nature. 2008;452(7187):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature06810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frias-Lopez J, Shi Y, Tyson GW, Coleman ML, Schuster SC, Chisholm SW, Delong EF. Microbial community gene expression in ocean surface waters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(10):3805–3810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708897105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457(7228):480–484. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendure J, Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(10):1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Alvarez V, Teal TK, Schmidt TM. Systematic artifacts in metagenomes from complex microbial communities. Isme J. 2009;3(11):1314–1317. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jaroszewski L, Godzik A. Clustering of highly homologous sequences to reduce the size of large protein databases. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(3):282–283. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.3.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jaroszewski L, Godzik A. Tolerating some redundancy significantly speeds up clustering of large protein databases. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(1):77–82. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437(7057):376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse SM, Huber JA, Morrison HG, Sogin ML, Welch DM. Accuracy and quality of massively parallel DNA pyrosequencing. Genome Biol. 2007;8(7):R143. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Stewart DA, Stromberg MP, Marth GT. Pyrobayes: an improved base caller for SNP discovery in pyrosequences. Nat Methods. 2008;5(2):179–181. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol. 2000;7(1-2):203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavromatis K, Ivanova N, Barry K, Shapiro H, Goltsman E, McHardy AC, Rigoutsos I, Salamov A, Korzeniewski F, Land M. Use of simulated data sets to evaluate the fidelity of metagenomic processing methods. Nat Methods. 2007;4(6):495–500. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poretsky RS, Hewson I, Sun S, Allen AE, Zehr JP, Moran MA. Comparative day/night metatranscriptomic analysis of microbial communities in the North Pacific subtropical gyre. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11(6):1358–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JA, Field D, Huang Y, Edwards R, Li W, Gilna P, Joint I. Detection of large numbers of novel sequences in the metatranscriptomes of complex marine microbial communities. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e3042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]