Abstract

Double stranded RNA has become a ubiquitous tool for inhibition of gene expression in the laboratory. If similar success could be achieved in vivo, duplex RNA might provide a new class of therapeutics capable of treating a broad spectrum of disease. Chemists and biologists developing duplex RNA as a drug have made progress but continue to face challenges. This review presents the current status of duplex RNA in the clinic and comments on future prospects for the approach.

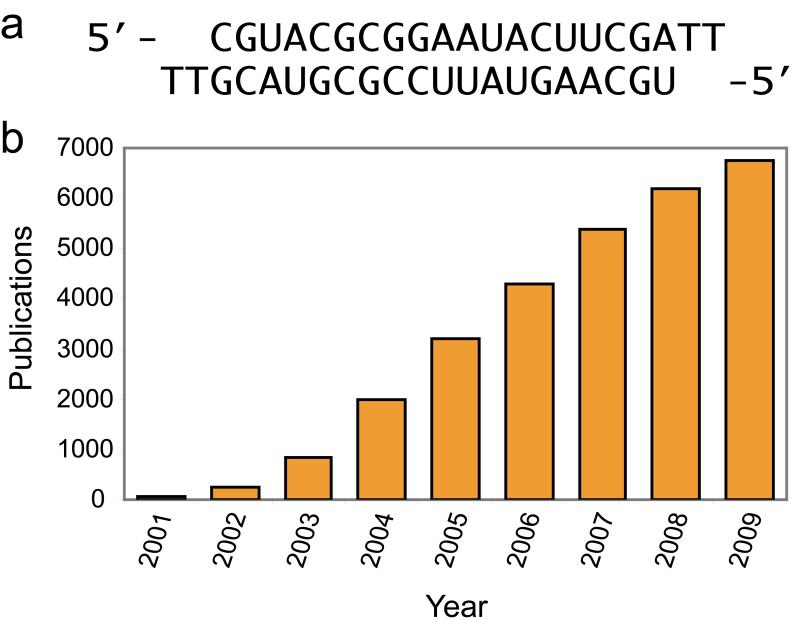

Double stranded RNAs can modulate gene expression through recognition of RNA transcripts.1 In 1998, Fire and Mello focused attention on the potential of duplex RNA as a regulatory agent by showing that long RNA duplexes could silence gene expression in C. elegans.2 In 2001, Tuschl demonstrated that short interfering RNAs (siRNAs, Figure 1a) could block gene expression in mammalian cells.3 The immediate consequence of Tuschl’s discovery was to provide a new experimental tool for laboratory research. Since 2008, the annual number of publications identified using the keyword “siRNA” on PubMed has been over 6000 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Structure of a typical siRNA.3 (b) Publications citing “siRNA” from 2001 to 2009.

The fact that this technology was so rapidly adopted by the scientific community is informative. Researchers have found that duplex RNA provides a robust and potent approach to controlling the expression of specific genes in mammalian cells. Gene silencing by siRNAs is effective because it can harness endogenous protein machinery, the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC), which exists to facilitate recognition of cellular RNA.4

If the ability of duplex RNA to repress the expression of many important genes in the laboratory could be replicated in the clinic, siRNAs might provide an important new class of therapeutic agents.5-7 Successful development, however, has required overcoming several challenges. Some of these challenges would confront the development of any drug, while others are unique to duplex RNA.

RNA is notorious for being an unstable molecule that requires careful handling in the laboratory. Double-stranded RNA, however, is much more stable than single-stranded RNA. This stability contributes to the robust results in cell culture and it is possible that some siRNA sequences may be stable enough to function effectively as drugs. However, many chemical modifications are available to enhance stability in vivo without compromising activity8,9 and it is likely that most drug candidates will be chemically modified. siRNAs are often vulnerable to cleavage at specific positions (for example, between two pyrimidine nucleotides), and including modified nucleotides at these positions is often enough to substantially increase the half-life of the siRNA.10 Several heavily or fully modified siRNA designs have been developed that are extremely resistant to nuclease cleavage.8 Thus the stability problem appears to have an adequate solution.

Another problem that has received widespread attention is the potential for RNAs to induce “off-target” effects (i.e. unintended alteration of nontarget gene expression). Any lead compound for drug development will have unexpected effects when introduced into cells, and siRNAs are no different. Like other synthetic molecules, the solution to the problem is to appreciate the causes for off-target effects and then design modified siRNAs to maximize selectivity while retaining potency.

There are several sources of off-target effects.11,12 As little as complementarity to bases 2-8 between the siRNA and an unintended miRNA target can cause gene repression. Just as the power of the RISC machinery makes siRNAs robust agents for silencing gene expression, it also facilitates unwanted interactions. One solution is to test several siRNAs to identify a candidate that is a potent silencing agent but has a minimal ability to induce unwanted phenotypes by blocking expression of other genes. Chemical modifications can also reduce the likelihood that imperfectly paired duplex RNAs can yield significant gene silencing.11

The RISC machinery is part of a natural mechanism for controlling processes with endogenous duplex RNAs. It is possible, therefore, that introduction of synthetic duplex RNAs can overwhelm the RISC machinery and prevent it from performing its normal function, thereby leading to unexpected consequences.11 Using the lowest possible concentration of RNA needed to observe silencing will reduce the likelihood that the RISC machinery will become saturated.

Double-stranded RNA can induce cellular changes through induction of interferons and other cytokines by the innate immune system.12-14 While the interferon response is especially obvious for duplex RNAs greater than 30 bases long, it has also been observed for siRNAs in vivo. Avoiding certain sequence motifs can reduce the interferon response, and the immuno-stimulatory potential of siRNAs can be further reduced through the introduction of chemical modifications.13,14

Once potent and specific siRNAs are identified by testing in cell culture they can be tested in animals. Compared to the large number of studies using siRNAs in cell culture, there have been relatively few studies using duplex RNAs in animals and the obvious widespread usefulness of siRNAs as an experimental tool in vivo has not been apparent. This slow progress reflects the difficulty of delivering large polyanionic synthetic materials to tissues that contain disease targets in vivo. Upon intravenous administration, naked RNA localizes predominantly to the liver and kidneys and most is rapidly cleared in the urine.15

It is likely that delivery strategies will continue to improve, with improved potencies and wider delivery to different tissues. The challenge of developing ideal delivery methods, however, has not postponed clinical trials with siRNAs. At least eleven siRNA drugs currently in clinical trials. In addition, two of the first drugs to begin trials have now been withdrawn (Table 1). Over 1500 patients and volunteers have already been dosed with siRNAs.

Table 1.

siRNA drugs in clinical trials.

| company | drug name | phase | target gene and disease | chemically modified? |

delivery (vehicle, if known) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alnylam | ALN-RSV01 | II | RSV (viral nucleocapsid) | no | intranasal or inhaled |

| Quark/Pfizer | PF-04523655 | II | RTP801 for wet AMD or diabetic macular edema |

yes | intraocular |

| Quark | QPI-1002 | II | p53 for acute renal failure | yes | intravenous |

| ZaBeCor | Excellair | II | SYK kinase for asthma | unknown | inhaled |

| Calando | CALAA-01 | I | Ribonucleotide reductase (RRM2) for solid tumors |

no | intravenous (targeted CD nanoparticle) |

| TransDerm | TD101 | Ib | Keratin 6a (N171K mutation) for Pachyonychia Congenita |

unknown | intradermal injection |

| Alnylam | ALN-VSP01 | I | VEGF and KSP for liver cancer | yes | intravenous (lipid nanoparticle) |

| Silence (Atugen) |

Atu-027 | I | PKN3 for solid tumors – specifically tumor vasculature |

yes | intravenous (lipid nanoparticle) |

| Tekmira | ApoB SNALP | I | ApoB for hypercholesterolemia | yes | intravenous (lipid nanoparticle) |

| Sylentis | SYL-040012 | I | ADRB2 for ocular hypertension (glaucoma) |

unknown | intraocular |

| Quark | QPI-1007 | I | Caspase-2 for glaucoma or acute eye injury |

yes | intraocular |

|

| |||||

| Drugs that have been withdrawn from clinical trials | |||||

|

| |||||

| OPKO (Acuity) | Bevasiranib | III | all VEGF-A isoforms for wet AMD |

no | intraocular |

| Sirna/Merck with Allergan |

AGN-211745 | II | VEGF receptor (VEGF-R1) for wet AMD |

yes | intraocular |

Starting local

While siRNA technology is a relatively new development, two oligonucleotide drugs using older technologies have been approved by the FDA: an antisense oligonucleotide for cytomegaloviral (CMV) retinitis and an aptamer against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Neither of these drugs is in widespread use today because of better other treatment options. However, these oligonucleotides demonstrated the potential of intraocular administration of oligonucleotides and it is not surprising that the first two siRNA drugs to begin clinical trials were administered to the eye.

Both these drug candidates targeted the VEGF pathway for the treatment of AMD and diabetic macular edema. After initial promising results they were both withdrawn from clinical trials. Part of the reason for their withdrawal may be that wet AMD, until recently considered incurable, is now responding well to treatment with Lucentis (ranibizumab), an anti-VEGF antibody fragment developed by Genentech.16 Also, a study showed that the anti-angiogenic effects of naked duplex RNAs delivered to the eye were mediated by the innate immune system, not by the RNAi pathway at all.17 This study also showed that while naked siRNA was not taken up by choroidal cells after intravitreal injection, conjugation to cholesterol did lead to cellular uptake and genuine RNAi activity.17

In spite of these setbacks, the eye is still a popular target tissue for siRNA drug candidates – one drug is now in Phase II and two others recently entered Phase I trials. It is unclear whether these drugs make use of conjugation or delivery vehicles to ensure cellular uptake, or whether their RNAi mechanism of action has been validated in vivo. Two of the three current drug candidates for eye targets are being developed by Quark Pharmaceuticals. Their most advanced drug, developed in partnership with Pfizer, inhibits expression of the hypoxia-responsive gene RTP80118 to treat wet AMD and diabetic macular edema.19 While these RNAs are designed to treat the same diseases as the withdrawn drugs, their target genes are different. Preliminary data indicated stabilization of visual acuity in 90% of patients and improved vision in some cases.

The other two drug candidates in the eye are related to ocular hypertension and glaucoma. Quark recently began Phase I trials on an siRNA that silences Caspase-II for protection against glaucoma or acute eye injury.19 Similarly, Sylentis began Phase I trials on a drug targeting ADRB2 to reduce ocular hypertension, a risk factor for glaucoma.20

The lung is another promising tissue for local delivery. Alnylam’s antiviral drug RSV-01 is an unformulated, unmodified siRNA. It is designed to treat respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the leading cause of pediatric hospitalization in the U.S. and a major concern for the elderly. RSV-01 targets the viral nucleocapsid gene and operates by a true RNAi mechanism in mouse models. This was shown using the most conclusive method of confirming RNAi mechanism: a technique called rapid amplification of 5′-cDNA ends (5′-RACE) that detects whether target mRNA is cleaved as predicted – at the linkage opposite the 10th and 11th nucleotides from the 5′-end of the guide strand.21 Such careful mechanistic work is important especially in light of the revelation that siRNA drugs targeting VEGF/VEGF-R1 in the eye were not operating by the RNAi pathway, as discussed above.17

RSV-01 has completed at least six clinical trials using both inhaled and intranasal routes of delivery. Four phase I trials demonstrated safety and tolerability.22 A phase II trial known as GEMINI enrolled 90 healthy volunteers who were experimentally infected with RSV. The results were favorable for safety and tolerability, and showed a 38.1% reduction in infection rate after treatment with intranasal RSV-01 compared with placebo.23 A smaller phase II trial on 24 RSV-positive lung transplant patients confirmed that the drug is well-tolerated, but this trial was not powered to evaluate efficacy. A larger Phase IIb trial in lung transplant recipients has just been initiated.23

A second-generation RSV drug is also in preclinical development by Alnylam.23 It will be interesting to see whether the introduction of chemical modifications and/or formulations will help improve the properties of the drug.

Another lung-targeted drug is being developed by ZaBeCor Pharmaceuticals. Excellair is an siRNA that targets SYK kinase and is in Phase II trials for asthma. Results from the Phase I trial showed that 75% of patients taking Excellair reported improved ability to breathe freely or reduced use of their rescue inhaler.24 SYK kinase is a signaling molecule early in the inflammation pathway, and reducing its expression may prove useful not only for asthma but other inflammatory diseases as well.24

The final tissue being targeted with local delivery is the skin. TransDerm Inc. is developing siRNAs that silence the N171K mutant allele of Keratin 6a as a method of treating pachyonychia congenita (PC), a rare congenital disorder characterized by thick nails and painful skin blisters.25 In a phase Ib trial, a single patient was given siRNA twice weekly for 14 weeks via microneedle arrays.26 While siRNA was effective in terms of alleviating symptoms, the patient found the regular injections hard to tolerate, especially given the additional tenderness caused by PC. The company is now focusing on alternative delivery technologies including a topical cream containing siRNA in a lipid-based formulation that can penetrate skin, and soluble tip microneedle arrays whose tips dislodge in the epidermis and release their cargo in a controlled fashion.25

Systemically administered siRNAs

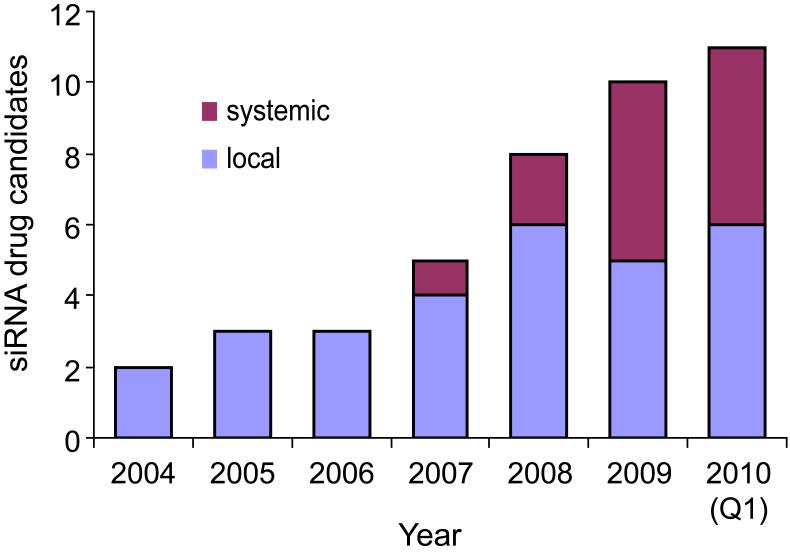

The trials described above involved local delivery of an siRNA to its site of action. Local delivery tolerates the use of less-sophisticated delivery strategies and involves lower risks that siRNA will be taken up by other tissues and cause side effects. Locally delivered siRNA drugs also tend to require less material and therefore cost less per administration. Given these advantages, it is not surprising that locally administered siRNA drugs were in clinical trials three years before any systemic siRNAs. However, in the past few years, systemically administered siRNAs have caught up to the point that the drugs currently in trials are evenly divided between systemic and local delivery (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Local and systemic siRNA drugs in clinical trials by year.

The first organ for which in vivo proof-of-concept data was obtained in animal models was the liver. In 2004, researchers at Alnylam showed RNAi activity in the liver after systemic injection of cholesterol-conjugated siRNAs into mice.27 The liver is still one of the best target organs for systemically delivered siRNA. However, siRNA can now be delivered to the liver with higher potency by using lipid-based nanoparticles.

Tekmira Pharmaceuticals has developed a nanoparticle containing cationic lipids for cellular uptake, neutral lipids that promote endosomal release, and PEG lipids to promote a long half-life in serum and help prevent aggregation.28 The resulting particles have a well-defined size (tunable from 40-140 nm) and a long shelf life. Depending on the precise lipids used, potency can be increased and the target organ can be tuned. The most advanced applications of these lipid nanoparticles, however, are in the liver.

One challenge of lipid-based delivery is that the siRNA payload is delivered directly into the endosomes, the location of the highest concentration of TLR-7. Therefore siRNAs delivered by lipid nanoparticles are particularly vulnerable to immune effects if not carefully modified. It is no coincidence that Tekmira has invested substantial resources in understanding and reducing immune stimulation of siRNAs.13,14

Tekmira’s lipid nanoparticles are being used to deliver two drugs in Phase I clinical trials. The first, Alnylam’s drug VSP-01, contains siRNAs against the VEGF and kinesin spindle protein (KSP) genes for solid tumors, particularly liver cancer. VEGF is a well-known anti-angiogenic target, and KSP knockdown helps prevent cell proliferation, therefore these two targets inhibit distinct aspects of tumor growth. In various animal models of liver cancer, this combination of siRNAs led to robust antitumor efficacy. It has also shown efficacy against disseminated tumors outside of the liver in animal models.23

The RNAi mechanism of VSP-01 was confirmed in mouse models with 5′-RACE; both genes were cleaved at the predicted site.23,29 The duration of gene silencing closely correlated with the duration of existence of the appropriate RACE fragment.29

Besides VSP-01, Tekmira is also using their lipid nanoparticle platform to deliver their own siRNA that targets the ApoB gene for treatment of hyperchol-esterolemia. Their drug ApoB SNALP entered a 23-subject escalating single-dose trial in 2009.28 Tekmira decided to terminate the trial after one patient at the highest dose level showed flu-like symptoms, indicative of immune stimulation. They plan to recommence clinical trials on ApoB SNALP in 2010 using improved siRNA chemistry and an improved nanoparticle formulation to minimize immune effects and improve potency.28

Tekmira and their partners expect to have five drugs using their lipid nanoparticle in clinical development by the end of 2010,28 including an siRNA therapy for transthyretin (TTR)-mediated amyloidosis for which Alnylam has already requested approval to begin Phase I trials.23

Other organs are also being pursued as options for systemic delivery. Silence Therapeutics (formerly Atugen) has developed a lipid nanoparticle called the AtuPLEX. Like Tekmira’s lipid nanoparticles, it contains cationic lipids to condense the siRNA and interact with cells, helper lipids to ensure endosomal release, and PEG lipids to protect the particles from aggregation and increase their serum half-life.30

Atu-027 is an AtuPLEX/siRNA that delivers siRNA predominantly to the vascular endothelium.31 The cargo is a blunt-ended 19-23 bp siRNA containing alternating native and 2′-OMe-modified nucleotides. It targets the protein kinase N3 (PKN3) gene in the tumor vasculature of patients with advanced solid cancer. In preclinical studies, Atu-027 showed significant anticancer activity against a broad range of tumor types including pancreatic, liver, non-small-cell lung and melanoma.32 A Phase I dose-finding trial is underway with plans to include about 33 patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors.

When unformulated oligonucleotides are injected intravenously, most of the material passes through the kidneys to the urine within a few hours.15 Thus it is not surprising that the first systemically administered siRNA drug to enter clinical trials was Quark’s kidney-targeted drug QPI-1002. It is also the only systemically administered siRNA in Phase II trials. By temporarily knocking down p53 in the kidney, QPI-1002 seeks to prevent acute kidney injury during surgery.33 It may also be useful in preventing graft rejection after kidney transplantation. Safety data from Phase I trials was favorable;19 we do not know whether the previous trials on QPI-1002 also examined efficacy.

Calando Pharmaceuticals has a systemically administered drug in a Phase I trial on about 36 patients with solid tumors.34 Calando’s delivery platform is a ~100-nm nanoparticle like those described above, but it is unique in several respects. Firstly, it is not a lipid-based particle, but rather is made of cationic cyclodextrin polymers. Secondly, it is targeted specifically to tumor cells by use of a transferrin ligand (since tumor cells have more transferrin receptors than other types of cells). Thirdly, this delivery method has been reported to be less immunogenic than lipoplex-mediated delivery, allowing Calando to use unmodified RNA.35 CALAA-01 combines this targeted cyclodextrin delivery system with an siRNA targeting ribonucleotide reductase subunit M2, an enzyme required for DNA synthesis. Experiments with biopsy samples from participants in the trial showed dose-dependent accumulation of nanoparticles in tumors and confirmed that the drug operates by an RNAi mechanism as shown by 5′-RACE.36 As of November 2009, the drug was well-tolerated and no significant drug-related toxicity had been observed. It remains to be seen whether either targeted nanoparticles or the other lipid-based nanoparticles discussed above will be successful at the very challenging task of penetrating solid tumors to a sufficient degree to reverse the progression of the disease.

Future prospects

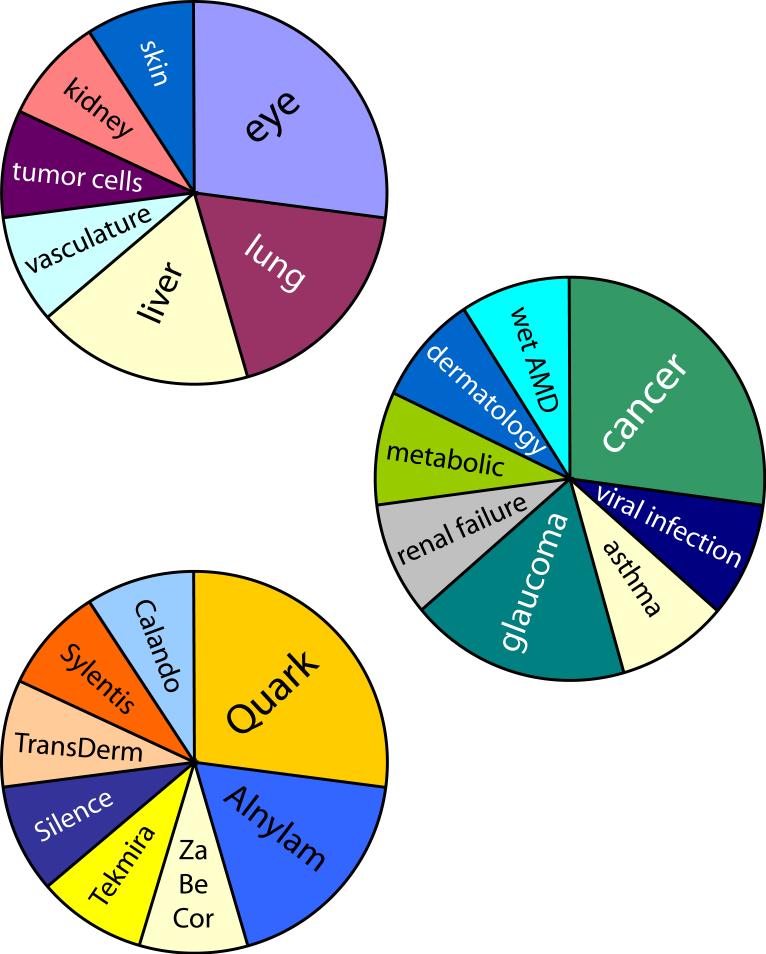

One of the most striking facts about the current status of siRNA clinical trials is the diversity of targets and players involved. The eleven drugs currently in the clinic cover eight conditions, in seven target tissues, from eight different companies (Figure 3). This is a testament to the versatility of siRNA as a therapeutic platform, but also to the fact that we are early in the process of siRNA drug development and no target organ or delivery platform has yet emerged as a proven route. This may begin to change if one or more delivery strategies emerges as a clear frontrunner. Locally delivered siRNA drugs may also begin to make more use of delivery vehicles. This idea is especially attractive in light of recent developments like the unexpected lack of uptake of naked siRNA by choroidal cells after intraocular delivery.17

Figure 3.

siRNA drugs in clinical trials classified by (top to bottom) target tissue, condition, and primary sponsoring company.

The field of oligonucleotide therapeutics may be further energized by the progress of ISIS Pharmaceuticals’ anti-ApoB antisense drug mipomersen, which has just completed its second successful Phase III clinical trial. These are the first Phase III trials on a systemically administered oligonucleotide drug to consistently meet its primary endpoints, and have important lessons for those of us in related fields: for example, the use of optimized chemistry and the fact that progress could be monitored by a simple blood draw contributed a great deal toward the success of this compound.

It is an exciting time in the field of siRNA therapeutics, with more drugs than ever in clinical trials and some important lessons being learned. With this momentum across such a diverse pipeline, it is likely that duplex RNA is in the clinic to stay.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIGMS 60642 and 73042 to DRC), the Robert A Welch Foundation (I-1244), and by the Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies [postdoctoral fellowship to JKW].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siomi H, Siomi MC. Nature. 2009;457:396. doi: 10.1038/nature07754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Nature. 1998;391:806. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Nature. 2001;411:494. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jinek M, Doudna JA. Nature. 2009;457:405. doi: 10.1038/nature07755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castanotto D, Rossi JJ. Nature. 2009;457:426. doi: 10.1038/nature07758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tiemann K, Rossi JJ. EMBO Mol. Med. 2009;1:142. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurreck J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:1378. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watts JK, Deleavey GF, Damha MJ. Drug Discov. Today. 2008;13:842. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corey DR. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3615. doi: 10.1172/JCI33483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Fougerolles A, Vornlocher H-P, Maraganore J, Lieberman J. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:443. doi: 10.1038/nrd2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson AL, Linsley PS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:57. doi: 10.1038/nrd3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olejniczak M, Galka P, Krzyzosiak WJ. Nucl. Acids Res. 2010;38:1. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robbins M, Judge A, MacLachlan I. Oligonucleotides. 2009;19:89. doi: 10.1089/oli.2009.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judge A, MacLachlan I. Hum. Gene Ther. 2008;19:111. doi: 10.1089/hum.2007.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braasch DA, Paroo Z, Constantinescu A, Ren G, Oz OK, Mason RP, Corey DR. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:1139. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melnikova I. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:711. doi: 10.1038/nrd1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, Chandrasekaran V, Nozaki M, Baffi JZ, Albuquerque RJC, Yamasaki S, Itaya M, Pan Y, Appukuttan B, Gibbs D, Yang Z, Karikó K, Ambati BK, Wilgus TA, DiPietro LA, Sakurai E, Zhang K, Smith JR, Taylor EW, Ambati J. Nature. 2008;452:591. doi: 10.1038/nature06765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoshani T, Faerman A, Mett I, Zelin E, Tenne T, Gorodin S, Moshel Y, Elbaz S, Budanov A, Chajut A, Kalinski H, Kamer I, Rozen A, Mor O, Keshet E, Leshkowitz D, Einat P, Skaliter R, Feinstein E. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:2283. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2283-2293.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. www.quarkpharma.com.

- 20. www.sylentis.com.

- 21.Alvarez R, Elbashir S, Borland T, Toudjarska I, Hadwiger P, John M, Roehl I, Morskaya SS, Martinello R, Kahn J, Van Ranst M, Tripp RA, DeVincenzo JP, Pandey R, Maier M, Nechev L, Manoharan M, Kotelianski V, Meyers R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3952. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVincenzo J, Cehelsky JE, Alvarez R, Elbashir S, Harborth J, Toudjarska I, Nechev L, Murugaiah V, Van Vliet A, Vaishnaw AK, Meyers R. Antiviral Res. 2008;77:225. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. www.alnylam.com.

- 24. www.zabecor.com.

- 25. www.transderminc.com.

- 26.Leachman SA, Hickerson RP, Schwartz ME, Bullough EE, Hutcherson SL, Boucher KM, Hansen CD, Eliason MJ, Srivatsa GS, Kornbrust DJ, Smith FJ, McLean WI, Milstone LM, Kaspar RL. Mol Ther. 2010;18:442. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soutschek J, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Charisse K, Constien R, Donoghue M, Elbashir S, Geick A, Hadwiger P, Harborth J, John M, Kesavan V, Lavine G, Pandey RK, Racie T, Rajeev KG, Rohl I, Toudjarska I, Wang G, Wuschko S, Bumcrot D, Koteliansky V, Limmer S, Manoharan M, Vornlocher H-P. Nature. 2004;432:173. doi: 10.1038/nature03121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. www.tekmirapharm.com.

- 29.Judge AD, Robbins M, Tavakoli I, Levi J, Hu L, Fronda A, Ambegia E, McClintock K, MacLachlan I. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:661. doi: 10.1172/JCI37515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santel A, Aleku M, Keil O, Endruschat J, Esche V, Fisch G, Dames S, Loffler K, Fechtner M, Arnold W, Giese K, Klippel A, Kaufmann J. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1222. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aleku M, Schulz P, Keil O, Santel A, Schaeper U, Dieckhoff B, Janke O, Endruschat J, Durieux B, Roder N, Loffler K, Lange C, Fechtner M, Mopert K, Fisch G, Dames S, Arnold W, Jochims K, Giese K, Wiedenmann B, Scholz A, Kaufmann J. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9788. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. www.silence-therapeutics.com.

- 33.Komarov PG, Komarova EA, Kondratov RV, Christov-Tselkov K, Coon JS, Chernov MV, Gudkov AV. Science. 1999;285:1733. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5434.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. www.calandopharma.com.

- 35.Heidel JD, Yu Z, Liu JY-C, Rele SM, Liang Y, Zeidan RK, Kornbrust DJ, Davis ME. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701458104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD, Ribas A. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature08956. advance online publication, doi: 10.1038/nature08956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]